Abstract

The sustainability of the agricultural system has become a global concern. Although the growth driven by green revolution technology has significantly contributed to making India self-sufficient in food production, the sustainability of the agricultural system has become debatable due to its adverse impact on the environment. Organic farming has become an alternative farming system to improve agricultural sustainability, yet farmers hesitate to adopt it. Therefore, this study aims to (i) identify the factors that affect the adoption of organic farming and (ii) investigate farmers’ perceptions towards its adoption. A total of 600 farmers (i.e., 300 organic and 300 conventional farmers) were randomly selected to conduct a field survey from two districts of the Middle Ganga River basin, India. A binary logistic regression was used to identify the factors that could affect the adoption of organic farming in the region. The results show that region, education, social category, training, farming experience, and monthly household income significantly affect organic farming adoption. Moreover, lack of financial support, lower yield levels, unavailability of markets, and expected low profits in organic farming are significant reasons that discourage farmers from adopting it. Therefore, by identifying significant variables associated with its adoption, the current study’s findings can provide better information for policymakers, which may help them make policies related to increasing the adoption rate among farmers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Agriculture plays a significant role in the development of an economy like India. It provides a livelihood for more than one-third of the population and contributes about 20% to the national GDP (GoI 2022). Further, with the continuously growing population in India, the demand for food increased, which put pressure on agricultural land (Chatterjee 2011). The technical change promoted through the green revolution in the 1960s played a significant role in enhancing agricultural productivity and helped India become self-sufficient in food grains. But its impact did not last for a longer period, and the sustainability of the Indian agricultural system has become questionable. The intensive use of agrochemicals such as fertilizers and pesticides/insecticides has decreased soil fertility, resulting in stagnation of agricultural productivity in recent years and environmental degradation (Narayanan 2005; Priya and Singh 2022). Hence, the adoption of organic farming is considered one of the strategies for sustainable agricultural growth. It has been proven to be one of the sustainable methods to address environmental challenges and enhance productivity (Aryal et al. 2018; Rigby and Cáceres 2001; Tey et al. 2014).

“Organic farming is a holistic production management system which promotes and enhances agro-ecosystem health, including biodiversity, biological cycles, and soil biological activity” (FAO 2015). It is considered an alternative to chemical farming that largely avoids synthetic chemicals and depends on crop rotation, crop residues, green manure, bio-fertilizers, and bio-pesticides (Azam & Shaheen 2019; Narayanan 2005; Ramesh et al. 2005). National and international research institutions have taken several initiatives to promote organic farming. Similarly, in India, central and state governments and various organizations and NGOs (e.g., APEDA, ICAR) are promoting organic farming. Moreover, Pramparagat Krishi Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), Mission Organic Value Change Development for North Eastern Region (MOVCDNER), National Mission on Oilseeds and Oil Palms (NMOOP), National Food Security Mission (NFSM), Rashtriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY), and National Project on Organic Farming (NPOF) are some of the initiatives taken by the Indian government for its promotion.

Because of several policy initiatives, the cultivated area under organic farming in India increased from 0.78 million ha in 2010–2011 to 2.66 million ha in 2021 (Manik & Tanwar, 2021). As per the FIBL & IFOAM Year Book 2022, India ranked 4th in terms of area under organic cultivation. Although India’s share of organic agricultural land has increased from 0.1% in 2005 to 1.08% in 2018, the growth rate is still low, and farmers hesitate to convert conventional farming to organic farming (Chadha & Srivastava 2020).

Additionally, the Indo-Gangetic Plain is agriculturally the most fertile region of the country (Aryal et al. 2018). However, the toxic chemicals used in intensive cultivation in the Gangetic plains eventually end up in the water bodies and pollute the river system (Shah & Parveen 2021). Hence, to curb it, the Indian government runs a campaign to develop organic farming corridors along the Ganga River in five states through which it passes (starting from Gangotri in Uttarakhand to Ganga Sagar in West Bengal). The main aim of the campaign is to promote organic farming clusters in a 5 km stretch on both sides of the Ganga River. Moreover, the regional governments of Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh are also encouraging the practice of organic farming in the Ganga River basin with a scheme called the Organic Agriculture Development Scheme or Jaivik Krishi Vikas Yojan (2020). However, the rate of adoption is slow in the area. There are various factors studied in the literature that affect the adoption of organic farming; however, it differs in the geographic and biophysical characteristics of the area. Hence, there is a need to conduct study for a better understanding of the adoption rate among farmers in the Indo-Gangetic Plain.

In the existing literature, the significant factors that affect the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices, including organic farming, have been divided mainly into six categories, viz. socio-economic, agro-ecological, institutional, technological, financial, and psychological (Ashari et al. 2017; Knowler & Bradshaw 2007; Lesch & Wachenheim 2014; Melisse 2018; Mozzato et al. 2018; Priya & Singh 2022). The common factors in the socio-economic dimension are gender, age, education, ethnicity, experience, household size, and household income. It has been observed in the studies done by Kassie et al. (2020) and Okon & Idiong (2016) that aged farmers are less likely to adopt new technologies due to their risk aversion behavior. Further, education plays an essential role in adoption; higher education often introduces farmers to new ideas and enhances their environmental concerns (Digal & Placencia 2019; Joshi et al. 2019; Xie et al. 2015).

Since organic farming is labor-intensive, farmers with larger household sizes are expected to adopt organic farming earlier than those with smaller household sizes (Tey et al. 2014). Further, more investment in improved technologies is significantly affected by higher farming experience (Ganpat et al. 2014; Lemeilleur 2013). However, Kunzekweguta et al. (2017) and Srisopaporn et al. (2015) find the farming experience to be an insignificant variable in the adoption. Additionally, farmers with larger farms are more willing to invest in new technologies due to their greater capacity for investment and risk undertaking (Rajendran et al. 2016; Tey et al. 2014). However, literature also shows farm size as an insignificant adoption variable (Chichongue et al. 2020; Laosutsan et al. 2019).

The extension services by various agencies such as the government, NGOs and farmers provide training to the farmers and motivate them to adopt sustainable agricultural practices (Chichongue et al. 2020; Eliyas & Sumathi 2019; Okon & Idiong 2016). Further, farmers generally avoid taking risks by shifting from one farming system to another. Hence, financial factors like crop insurance and access to credit play a significant role in the adoption (Laxmi & Mishra 2007; Tey et al. 2014). Moreover, the literature shows that farmers’ perceptions and attitudes toward sustainable farming influence their adoption. They are more likely to adopt sustainable farming if they perceive that adoption would reduce the input cost and benefit human health and the environment (Joshi et al. 2019; Sarker et al. 2005; Sriwichailamphan et al. 2008).

Although several studies examine the factors affecting the adoption of organic farming globally, we hardly find any study on factors in the Middle Ganga River basin in India. Further, farmers’ opinion towards organic farming also plays an essential role in the adoption. Therefore, it is important to understand the adoption behavior of the farmers. Thus, this study aims to (i) identify the factors that affect the adoption of organic farming in the Middle Ganga River basin, India, and (ii) investigate farmers’ perceptions towards adopting organic farming in the study area. Therefore, by identifying significant factors associated with the adoption of organic farming, the findings of the current study can provide better information to the government and policymakers for designing effective plans for promoting organic farming in India. This study was motivated to understand the reasons for the non-adoption and adoption of organic farming among farmers in India, irrespective of significant efforts taken by the central and state governments. Such an understanding will help to show the different prospects available to enhance the adoption of organic farming for sustainable agricultural development in the study area. Further, this study is also important in accumulating the efforts to encourage sustainable agricultural practices that are environmentally sound and economically viable.

The sections of the current paper are designed as follows: in the “Materials and methods” section, we describe the materials and methods used in the study. The “Results” section discusses the results regarding the descriptive statistics of variables used in the model and the estimation of factors affecting the adoption. Further, in the “Discussion” section, the discussion of empirical results has been done. Finally, concluding remarks are provided in the “Conclusion” section.

Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the Middle Ganga River basin India. The Middle Ganga River basin lies from Haridwar in Uttarakhand to Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. Two districts, Haridwar and Bulandshahr, have been chosen for the primary data collection from the Middle Ganga River basin. Out of these two districts, 20 villages were selected for the final data collection of 600 farmers (organic = 300, conventional = 300). The data were collected through a semi-structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was divided into two sections: the first section includes the socio-economic, bio-physical and demographic characteristics of the farmers, whereas, in the second section, qualitative data regarding their perception towards organic farming were asked.

To study the factors affecting the adoption of organic farming, a binary logistic regression model has been applied for data analysis, which helps to predict the probability of occurrence of the events with specific sets of independent variables. This model is commonly used in the literature to assess the relationship between adoption and the associated factors (Digal & Placencia 2019; Mlenga 2015; Okon & Idiong 2016; Xie et al. 2015). The estimated model’s results will help to identify the factors that show a statistically significant relationship with the dependent variable, i.e., adoption. The standard functional form of a logit model is given by:

where β0 is a constant, β’s are the parameters, X’s are the independent variables, logit is the log of the odds ratio and can be shown as:

where Pi is the probability of the dependent variable taking the value 1 and Pi/1-Pi is the odds ratio. The higher the odds ratio, the higher the chances of the dependent variable taking the value 1. In the model applied here, the dependent variable was the adoption of organic farming; adopter is represented by 1 and non-adopter by 0. The functional form of the logistic regression model is given below:

Additionally, to summarize the impact of selected independent variables on the adoption of organic farming, marginal effects were also calculated. Marginal effects in logistic regression measure the probability of a change in the dependent variable due to a change in an independent variable. In contrast, regression coefficients show only directional change (Serebrennikov et al. 2020). Further, post-estimation tests were also used to validate the model. A variance inflation factor (VIF) was estimated to check the multicollinearity among the independent variables. Further, Hosmer–Lemeshow test was also used to test the model's goodness of fit. Previous literature about the adoption of organic farming includes various variables, viz. age, education, gender, extension services, training, farm size, perception towards organic farming, etc. (Knowler & Bradshaw 2007; Lesch & Wachenheim 2014; Mutyasira et al. 2018; Priya & Singh 2022). Therefore, initially, we included multiple variables for data analysis, but due to the high correlation among the variables, we narrowed down only those variables which were not significantly correlated. For example, age was highly correlated with years of farming experience; hence we deleted the age variable from the analysis. Finally, this study uses the following variables shown in Table 1.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 describes the overall descriptive statistics of variables used in estimating the model. It shows that, out of the total sample of 600 farmers, 569 were male and only 31 were female. Moreover, most of the farmers belonged to OBC social category (66%), followed by the general (28.33%) and SC (5.68%) categories. The adoption level among general social category farmers was higher than other categories since 70% of total general category farmers are adopters. Table 2 further demonstrates that compared to non-adopters, a more significant percentage of adopters have a primary and secondary level of education, approximately 62% and 58%, respectively. The mean education level of the total sampled farmers was middle school, followed by secondary and senior secondary. In contrast, it is secondary level among adopters and senior secondary level among non-adopters. But the adoption rate among farmers with primary education is the highest (61.70%). Among all, 67.17%of farmers have taken training, of which 63.77 were adopters of organic farming.

Moreover, the adopter farmers have a high average farming experience compared to non-adopter farmers, i.e., 35 and 23 years, respectively. Similarly, adopter farmers’ average monthly household income was more than two times higher than non-adopter farmers. Further, there is not much difference between the average household size among both categories; it is 5 for adopters and 4 for non-adopters.

Logistic regression

The results of the empirical model in Table 3 indicate that variables like region, social category, training, log of experience, and log of income play a statistically significant role in adopting organic farming in the study area. The positive significance (at a 5% level of significance) results of the region show that farmers belonging to the Haridwar region are more likely to adopt organic farming than Bulandshahr. Further, the social category also plays a vital role in adoption. The negative value of coefficients and marginal effects (dy/dx) indicate that farmers belonging to OBC and SC categories have approximately 16 and 21% fewer chances of adopting organic farming than the general category. Interestingly, the higher likelihood of adoption is associated with those with primary and secondary education levels; however, the adoption rate is 13 and 21%, respectively, in these two education categories.

On the other hand, the insignificant values of gender, marital status, household size, farm size, livestock, and distance from mandi (local market) show that adoption decision is not much affected by these variables in the study area. Further, farmers who have received any training on organic farming have a 22% greater likelihood of adopting organic farming. Additionally, farmers with more experience in farming and a high monthly household income have higher chances of adoption since their coefficient values are positively significant at a 1% significance level. The marginal effects show that farmers with higher income and experience have approximately 60 and 35% higher likelihood of adoption.

Moreover, the p-value of the model shows that model is statistically significant, and 81.83% is correctly classified. The Hosmer–Lemeshow (HL) goodness of fit test can be utilized to get an equivalent summary of the test statistic for the sample authentication and risk prediction (Midi et al. 2010). The nominal value of HL test shows no problem with the model or there is no risk in prediction. Further, the variables have no multicollinearity since all variables’ variance inflation factor (VIF) values are less than 10.

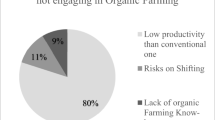

Perceptions of the farmers regarding adoption and non-adoption

Besides the above-discussed factors that affect the adoption, the perception of the farmers regarding organic farming also plays a significant role in adoption. Table 4 explains the reasons for conventional farmers’ non-adoption of organic farming. The primary reason for the non-adoption of organic farming is a lack of financial support, followed by lower yields. Previous study done by Digal & Placencia (2019) also proves low productivity as a primary reason for non-adoption. Difficulties in finding a market for their organic produce further demotivates farmers to shift from conventional to organic farming.

Additionally, 85% of conventional farmers give the reason for not adopting organic farming as low profit. However, only twelve percent of farmers perceived the organic input cost as higher than the chemical inputs. Still, they are not adopting it due to their perception of lower yield and unavailability of markets.

On the other hand, the common reasons for the adoption of organic farming by adopters are shown in Table 5. Ninety-five percent of organic farmers agreed that they adopted organic farming due to its potential positive impact on human health. However, 91% of organic farmers believed that organic farming is not profitable, but they adopted it only because of government incentives (90%). Nevertheless, 87% of farmers also accepted that soil and water conditions are deteriorating due to the overuse of agrochemicals.

Discussion

The current study determines factors affecting the adoption of organic farming in the Middle Ganga Region in India. The estimated results of regression analysis show that region, social category, education, training, experience, and household income are among the factors that significantly influenced farmers' decision to convert to organic farming. The active involvement of the governments through various policies can significantly increase the chance of greater adoption. For example, in Sikkim, the state government opted Organic Mission plan in 2003 as an initial step to becoming the first organic state by banning the import of chemical inputs, which resulted in Sikkim becoming the first fully organic state in India (Govt. of Sikkim 2022).

Similarly, the results of the study show that farmers in the Haridwar region are more likely to adopt organic farming; this might be because the region belongs to the state of Uttarakhand, where central and various state agencies are focusing majorly on promoting organic farming to make the state fully organic. For example, the state has established a dedicated nodal agency, Uttarakhand Organic Commodity Board (UOCB) (2003), to promote sustainable agricultural development through organic farming (Meena & Sharma 2015). The UOCB aims to provide training and organize seminars/exhibitions to promote organic products in the state. It also provides marketing and certification for organic products, resulting in 12 villages in Uttarakhand being declared bio-villages (Meena & Sharma 2015). Hence, we can say that government plays a significant role in promoting and adopting organic farming with a strong policy framework.

Further, our findings indicate that farmers belonging to SC and OBC social categories are less likely to adopt organic farming since coefficient values are negatively significant. These results are similar to the studies conducted by Aryal et al. (2018) and Singh & Sharma (2019) in the Indo-Gangetic plains of Bihar & Haryana and Rajasthan, respectively. Moreover, it has been observed in previous literature that education plays a significant role in adoption as it enhances farmers' knowledge and influences them to adopt (Aryal et al. 2018; Digal & Placencia 2019; Singh & Sharma 2019). But the estimated results of the current study indicate (Table 3) that farmers with only primary and secondary education levels are more likely to adopt organic farming. Farmers who are illiterate or have higher education are not interested in organic farming; it might be because 90% of farmers have opted for organic farming in the study area because of government incentives and support (Table 5).

Moreover, farmers with longer years of experience tend to be more receptive to adopting organic farming (Digal & Placencia 2019; Giannakis 2014). Possibly, due to the high farming experience, farmers could observe the adverse effects of input-intensive farming on high input costs and environmental degradation. The findings of the current study also indicate that farmers with more experience in farming are more likely to adopt organic farming. Similar results have been found by Kumar et al. (2010) and Lemeilleur (2013) in their study done in India and Peru, respectively.

Similarly, training in agriculture plays a positively significant role in adopting organic farming. Because the training provided by various governmental and non-governmental agencies disseminates information and enhances farmers’ technical skills, which helps to increase the adoption rate (Joshi et al. 2019; Kafle 2011; Raghu et al. 2014). Further, the results of descriptive statistics also justify that 63.77% of farmers have shifted farming from non-organic to organic farming after training and 78.17% of farmers who have not received training are non-adopters (see Table 2).

Additionally, farmers’ decision to convert to organic farming is an economic decision. Profitability is the most crucial factor for a farmer in making a farming decision (Koesling et al. 2008). The risk of having poor financial prospects demotivates farmers to adopt it due to initial yield loss in the transition period (Uematsu & Mishra 2012). And farmers with a high level of monthly household income have the capacity to bear that risk. The results of this study analyze that the monthly household income of the farmers significantly affects the adoption rate in the Middle Ganga River basin in India. Similar results have also been observed in the studies conducted by Laosutsan et al. (2019) and Senanayake & Rathnayaka (2015) in Thailand and Sri Lanka, respectively.

Moreover, farmers’ perceived attitude towards organic farming also plays an essential role in its adoption. The non-adopters perceived that lack of financial support, low level of yield and difficulties in finding the markets were the major hurdles to adopting. Hence, more focus should be given to the establishment of the organic market and providing them premium prices at least during the transition period (initials 2–3 years when production declines). Our results are consistent with the literature where production and marketing barriers are discovered as significant constraints to adopting organic farming (Nandi et al. 2015; Panneerselvam et al. 2012). Further, adopter farmers were more aware of the environmental degradation and adverse impact of chemical farming on their health. Hence, more seminars and extension services regarding organic farming can make farmers aware and motivate about its potential benefits on environment and human health.

The above discussion concludes that there are multiple socio-economic factors (ranging from region to training and family income) that affect the rate of adoption of organic farming. However, there might be some other important factors, for example socio-political, socio-cultural and psychological which can also affect the adoption rate, which have not studied in the current study. Thus, this study can open the scope of future research for the parallel study.

Conclusion

In view of improving the sustainability of agricultural systems in India, this study aimed to identify the factors that could affect the adoption of organic farming in the Middle Ganga River basin, India. The results of binary logistic shows that the significant factors that affect the adoption of organic farming were region, education, social category, farming experience, training and monthly household income. This analysis has important policy implications as it highlights the areas where the government can intervene in order to promote organic farming among conventional farmers. For example, farmers in the Haridwar region with primary and secondary education levels and the general social category are more likely to adopt organic farming. Further, farming experience, training, and monthly household income are other significant factors affecting farmers' adoption rates. Therefore, policies must be focused on educating farmers by organizing various training programs and extension services. It will help spread awareness of environmental pollution due to conventional farming.

Moreover, although farmers believe that the input cost under organic farming is lower, they did not adopt it for various reasons. Lack of financial support, lower yield levels and unavailability of markets under organic farming are significant reasons that discourage farmers from adopting it. Hence, the policy must be focused on establishing markets, raising yield through reorientation of research and development (R&D), and providing premium during the initial years of conversion. Further, another reason for less adoption is their belief in low profitability in organic farming. Therefore, various seminars and programs should be organized to motivate and guide them on how it becomes profitable. Moreover, the adopter showed attention to continuing it because of its potential impact on human health, followed by government incentives and support. The study suggests that government incentives can play a significant role in adopting organic farm practices in the Middle Ganga River basin. Further, this research also has certain limitations such as the limited number of variables due to the limited resources, hence more comprehensive research including more variables can be conducted for a more holistic picture. Moreover, this study limits the area to two districts in Middle Ganga river basin, hence in order to understand the impact of various factors on the adoption of organic farming in the entire Ganga river basin, the study area can be expanded to include upper and lower Ganga river basin for further research.

References

Aryal JP, Jat ML, Sapkota TB, Khatri-Chhetri A, Kassie M, Rahut DB, Maharjan S (2018) Adoption of multiple climate-smart agricultural practices in the Gangetic plains of Bihar, India. Int J Clim Change Strat Manage 10(3):407–427. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-02-2017-0025

Ashari, Sharifuddin, & Mohamed Zainal Abidin (2017). Factors determining organic farming adoption: international research results and lesson learned for Indonesia Faktor-Faktor yang Menentukan Adopsi Pertanian Organik: Hasil-Hasil Penelitian Internasional dan Pembelajaran untuk Indonesia. Forum Penelitian Agro Ekonomi, 35(1), 45–58

Azam MS, Shaheen M (2019) Decisional factors driving farmers to adopt organic farming in India: a cross-sectional study. Int J Soc Econ 46(4):562–580. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-05-2018-0282

Best H (2009) Organic farming as a rational choice: empirical investigations in environmental decision making. Ration Soc 21(2):197–224

Chadha D, Srivastava SK (2020) Growth performance of organic agriculture in India. Curr J Appl Sci Technol 39(33):86–94

Chatterjee P (2011). Democracy and economic transformation in India. Understanding India's New Political Economy, 33–50, Routledge, England, UK

Chichongue O, Pelser A, Tol JV, Du Preez C, Ceronio G (2020) Factors influencing the adoption of conservation agriculture practices among smallholder farmers in Mozambique. Int J Agri Ext 7(3):277–291. https://doi.org/10.33687/ijae.007.03.3049

Digal LN, Placencia SGP (2019) Factors affecting the adoption of organic rice farming: the case of farmers in M’lang, North Cotabato. Phil Org Agri 9(2):199–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-018-0222-1

Eliyas M, Sumathi P (2019) Factors influencing the adoption of recommended package of practices by pepper growers of Wayanad district. Kerala Int J Farm Sci 9(1):17. https://doi.org/10.5958/2250-0499.2019.00015.6

FAO. (2015). FAO definition of OF.pdf. FAO, Rome. https://www.fao.org/3/i5056e/i5056e.pdf. Accessed 15 Jul 2022

Ganpat W, Badrie N, Walter S, Roberts L, Nandlal J, Smith N (2014) Compliance with Good Agricultural Practices (GAPs) by state-registered and non-registered vegetable farmers in Trinidad. West Indies Food Sec 6(1):61–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-013-0322-4

Giannakis E (2014) Modelling farmers’ participation in agri-environmental schemes in Greece. Int J Agric Resour Gov Ecol 10(3):227–238. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJARGE.2014.064005

GoI, (2022). Economic Survey 2021–2022. Ministry of Finance, New Delhi, India. https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/ebook_es2022/index.html. Accessed 18 Jul 2022

Govt. of Sikkim, (2022). Sikkim organic mission. Horticulture Department. Sikkim, India. https://sikkim.gov.in/Mission/Mission-info/1?Mission=Sikkim%20Organic%20Mission#:~:text=The%20Government%20of%20Sikkim%20stepped,traditional%20users%20of%20organic%20manure. Accessed 2 Sep 2022

Habanyati EJ, Nyanga PH, Umar BB (2020) Factors contributing to disadoption of conservation agriculture among smallholder farmers in Petauke. Zambia Kasetsart J Soc Sci 41(1):91–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2018.05.011

Heena, Malik DP, Tanwar N (2021) Growth in area coverage and production under organic farming in India. Economic Affairs 66(5):611–617. https://doi.org/10.46852/0424-2513.4.2021.13

Joshi A, Kalauni D, Tiwari U (2019) Determinants of awareness of good agricultural practices (GAP) among banana growers in Chitwan. Nepal J Agri Food Res 1:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafr.2019.100010

Kafle B. (2011). Factors affecting adoption of organic vegetable farming in Chitwan district, Nepal. World J Agri Sci, 7(5), 604–606. https://doaj.org/article/90c2125ec8474f25a3b01404732b8d39

Kassie M, Zikhali P, Manjur K, Edwards S (2020). Adoption of organic farming technique: evidence from a Semi-Arid Region of Ethiopia. Environ Develop Initiative, 2009.

Knowler D, Bradshaw B (2007) Farmers’ adoption of conservation agriculture: a review and synthesis of recent research. Food Policy 32(1):25–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2006.01.003

Koesling M, Flaten O, Lien G (2008) Factors influencing the conversion to organic farming. Int J Agric Resour Gov Ecol 7(1–2):78–95

Kumar A, Prasad K, Kushwaha RR, Rajput MM, Sachan BS (2010) Determinants influencing the acceptance of resource conservation technology: case of zero-tillage in rice-wheat farming systems in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Haryana states. Indian J Agri Econ 65(3):448–460

Kunzekweguta M, Rich KM, Lyne MC (2017) Factors affecting adoption and intensity of conservation agriculture techniques applied by smallholders in Masvingo district. Zimbabwe Agrekon 56(4):330–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2017.1371616

Laosutsan P, Shivakoti GP, Soni P (2019) Factors influencing the adoption of good agricultural practices and export decision of Thailand’s vegetable farmers. Int J Commons 13(2):867–880. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.895

Laxmi V, Mishra V (2007) Factors affecting the adoption of resource conservation technology: case of zero tillage in rice-wheat farming systems. Indian J Agri Econ 62(1):126–138

Lemeilleur S (2013) Smallholder compliance with private standard certification: the case of global GAP adoption by mango producers in Peru. Int Food Agribusiness Manage Rev 16(4):159–180

Lesch WC, Wachenheim CJ (2014). Factors influencing conservation practice adoption in agriculture: a review of the literature. Agribusiness Appl Econ Rep 722, March, 29. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/164828/

Meena VS, Sharma S (2015) Organic farming: a case study of Uttarakhand Organic Commodity Board. J Ind Pollut Control 31(2):201–206

Melisse B (2018) A review on factors affecting adoption of agricultural new technologies in Ethiopia. J Agri Sci Food Res 9(3):1–6

Midi H, Rana S, Sarkar SK (2010) Binary response modeling and validation of its predictive ability. WSEAS Trans Math 9(6):438–447

Mlenga DH (2015) Factors influencing adoption of conservation agriculture: a case for increasing resilience to climate change and variability in Swaziland. J Environ Earth Sci 5(22):16–25

Mozzato D, Gatto P, Defrancesco E, Bortolini L, Pirotti F, Pisani E, Sartori L (2018) The role of factors affecting the adoption of environmentally friendly farming practices: can geographical context and time explain the differences emerging from literature? Sustainability (switzerland) 10(9):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093101

Mutyasira V, Hoag D, Pendell D (2018) The adoption of sustainable agricultural practices by smallholder farmers in Ethiopian highlands: an integrative approach. Cogent Food Agri 4(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2018.1552439

Nandi R, Bokelmanna W, Nithya VG, Dias G (2015) Smallholder organic farmer’s attitudes, objectives and barriers towards production of organic fruits and vegetables in India: a multivariate analysis. Emirates J Food Agri 27(5):396–406. https://doi.org/10.9755/ejfa.2015.04.038

Narayanan S (2005). Organic farming in India: relevance, problems and constraints. Nabard, 1–93

Okon UE, Idiong IC (2016) Factors influencing adoption of organic vegetable farming among farm households in south-south region of Nigeria. Am Eurasian J Agric Environ Sci 16(5):852–859. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2016.16.5.12918

Panneerselvam P, Halberg N, Vaarst M, Hermansen JE (2012) Indian farmers’ experience with and perceptions of organic farming. Renew Agric Food Syst 27(2):157–169. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170511000238

Pongvinyoo P, Yamao M, Hosono K (2014) Factors affecting the implementation of Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) among coffee farmers in Chumphon Province Thailand. Am J Rural Develop 2(2):34–39. https://doi.org/10.12691/ajrd-2-2-3

Priya, & Singh SP (2022). Factors influencing the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices: a systematic literature review and lesson learned for India. Forum for Soc Econ, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07360932.2022.2057566

Raghu PT, Manaloor V, Nambi VA (2014) Factors influencing adoption of farm management practices in three agrobiodiversity hotspots in India: an analysis using the count data model. J Nat Res Develop 04:46–53. https://doi.org/10.5027/jnrd.v4i0.07

Rajendran N, Tey YS, Brindal M, Ahmad Sidique SF, Shamsudin MN, Radam A, Abdul Hadi AHI (2016) Factors influencing the adoption of bundled sustainable agricultural practices: a systematic literature review. Int Food Res J 23(5):2271–2279

Ramesh P, Singh M, Subba Rao A (2005) Organic farming: its relevance to the Indian context. Curr Sci 88(4):561–568

Reganold JP, Wachter JM (2016) Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat Plants 2:15221. https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2015.221

Rigby D, Cáceres D (2001) Organic farming and the sustainability of agricultural systems. Agric Syst 68(1):21–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0308-521X(00)00060-3

Sarker, M. A., Itohara, Y., & Hoque, M. (2005). Determinants of adoption decisions: the case of organic farming (OF) in Bangladesh. Extension Farming Syst J, 5(2), 39–46. http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=733506527698660;res=IELHSS. Accessed 8 Sep 2022

Senanayake SS (2015) Rathnayaka RMSD (2015) Analysis of factors affecting for adoption of good agricultural practices in potato cultivation in Badulla district Sri Lanka SS Senanayake. Agrieast 10:16–26

Serebrennikov D, Thorne F, Kallas Z, McCarthy SN (2020) Factors influencing adoption of sustainable farming practices in Europe: a systemic review of empirical literature. Sustainability (switzerland) 12(22):1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229719

Shah ZU, Parveen S (2021) Pesticides pollution and risk assessment of river Gange: a review. Heliyon 7(8):e07726

Singh B, Sharma AK (2019) Factors affecting adoption of organic farming technology in arid zone. Ann Arid Zone 58(3&4):1–5

Srisopaporn S, Jourdain D, Perret SR, Shivakoti G (2015) Adoption and continued participation in a public Good Agricultural Practices program: the case of rice farmers in the Central Plains of Thailand. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 96:242–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.03.016

Sriwichailamphan T, Sriboonchitta S, Wiboonpongse A, Chaovanapoonphol Y (2008) Factors affecting good agricultural practices in pineapple farming in Thailand. Acta Horticulturae 794:325–334. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2008.794.40

Terano R, Mohamed Z, Shamsudin MN, Latif IA (2015) Factors influencing intention to adopt sustainable agriculture practices among paddy farmers in Kada. Malaysia Asian J Agri Res 9(5):268–275. https://doi.org/10.3923/ajar.2015.268.275

Tey YS, Li E, Bruwer J, Abdullah AM, Brindal M, Radam A, Ismail MM, Darham S (2014) The relative importance of factors influencing the adoption of sustainable agricultural practices: a factor approach for Malaysian vegetable farmers. Sustain Sci 9(1):17–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-013-0219-3

Uematsu H, Mishra AK (2012) Organic farmers or conventional farmers: where’s the money? Ecol Econ 78:55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.03.013

Willer H, Travnicek J, Meier C, Schlatter B (2022). The world of organic agriculture: statistics and emerging trends 2022. In Res Instit Org Agri FiBL IFOAM – Org Int. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijshe.2009.24910aae.004

Xie, Y., Zhao, H., Pawlak, K., & Gao, Y. (2015). The development of organic agriculture in China and the factors affecting organic farming. J Agri Rural Develop, 2(36353–361). https://doi.org/10.17306/JARD.2015.38

Funding

Professor S.P. Singh (first author) has received the funding from Indian Council of Social Science Research (ICSSR), New Delhi, India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Professor S.P. Singh has developed the idea for the current research and received the fund for the study. He assisted other authors in each and every step and finalized the draft of the manuscript. Priya has reviewed the relevant literature, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. Komal has helped in data collection and data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, S.P., Priya & Sajwan, K. Factors influencing the adoption of organic farming: a case of Middle Ganga River basin, India. Org. Agr. 13, 193–203 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-022-00421-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-022-00421-2