Abstract

Leaders’ support is crucial to improve employee engagement and job satisfaction; however, our understanding is limited regarding how servant leadership is perceived among employees with varying levels of conscientiousness. The current study examines how employees use crafting strategies (i.e. seeking resources, seeking challenges, and reducing demands) when exposed to servant leadership. Using the personality trait theory with an emphasis on conscientiousness, we propose that employees with high or low conscientiousness react differently to servant leadership by adopting varying job crafting strategies, which further promote or obstruct work outcomes (i.e. engagement and job satisfaction). The current study methodologically employed structure equation modelling to analyse a moderated mediation model from a sample of 362 hotel employees. The findings reveal that both work outcomes positively regress on seeking resources and challenges and negatively regress on reducing demand. The link between servant leadership and work outcomes is mediated by the job crafting behaviours. Evidently, conscientiousness moderates the link between servant leadership, seeking resources, and seeking challenges. The current study contributes to the existing literature by examining servant leadership’s interplay with employee reactions (i.e. job crafting behaviours) and work outcomes, which have implications for academia and practitioners that we have discussed in the current study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Servant leadership is a philosophical leadership stance where leaders emphasise on the well-being and the development of the employees rather on thriving of the organisation (Guillaume et al., 2013; Qiu et al., 2020; Song et al., 2015). Prior studies suggest that leaders with servant leadership philosophy are caring, welcoming, tolerant, accommodating, sympathetic, and help employees by listening to the problems employees face at work (Dooley et al., 2020; Jaramillo et al., 2009). A review of the literature further suggests that servant leadership emphasise on the ‘support for the employees’, which encompass several behaviours such as relations-oriented behaviours, paying attention to the job-related and psychosocial needs, and promoting the well-being of employees (Gui et al., 2021; Yukl, 2001). In this sense, not only the role of servant leadership is important but how subordinates perceive and react to servant leadership also becomes highly significant. The discussion so far clearly suggests the significance of servant leadership and its influence over employee perceptions; however, understanding the role of key underlining mechanisms is such relationships is quite limited. The current study thus aims to critically examine the significance of servant leadership for employee satisfaction and engagement via the key underlining mechanisms such as employee job crafting behaviours and employee conscientiousness.

Servant leadership can be seen through a lens of a hierarchical mentoring relationship, which involves mentor and protégé (Eby, 1997). As a mentor, it allows leaders to act as a role model for employees and facilitate employee learning, psychosocial well-being, and job-related competence (Khalil et al., 2021). From an employee perspective, our understanding is limited about how employees react to the servant leadership. Seeking this knowledge is important as it will help leaders to incorporate certain actions to guide employees during uncertainty and will uncover how employees adapt to servant leadership. In line with the work performance (Griffin et al., 2007; Khan et al., 2021) and job redesign methods (Grant & Parker, 2009) theory, the current study argues that subordinates adopt crafting strategies to respond to the leader’s support that subordinates receive. Furthermore, the current study proposes that job crafting strategies are self-initiated behaviours that employees use to redraw the boundaries of the jobs when exposed to servant leadership or the lack of servant leadership. In that sense, we are dealing here with not only the servant leadership, per se, but with the employee reactions occurring via job crafting.

Conscientiousness is a significant trait in the Big Five traits of personality theory (Roberts et al., 2005). Conscientiousness is a personal trait of being, responsible, self-controlled, exacting, determined, success-focused, systematic, and ambitious (Liu et al., 2022). Prior studies suggest that conscientiousness predicts performance across varying situations and occupations (Barrick et al., 1993; Judge et al., 1999). Being a personality trait, conscientiousness can be highly significant for analysis of how servant leadership is perceived and how it influences work outcomes. This area of research has received surprisingly limited attention from previous research and requires further attention. Therefore, we propose to critically examine the interplay between personality traits and behaviour (job crafting), which further influences work engagement and job satisfaction.

Building on the personality traits theory through conscientiousness, the current study argues that the response to servant leadership varies among employees. Job crafting, in this sense, can be seen as an employee’s strategy for reacting to and dealing with the perceived servant leadership. However, the level of an employee’s engagement in this behaviour depends on the personality traits (i.e. high conscientiousness vs. low conscientiousness) and employees’ perception of servant leadership. The first aim of the current study is, thus, to determine the effectiveness of servant leadership during job crafting through the moderating effect of conscientious (high vs. low).

The current study assumes that employees use job crafting strategies to respond to the support employees receive from leaders, one may ask if these crafting strategies are successful in facilitating positive support from leaders (i.e. servant leadership). The current study also attempted to critically analyse job crafting effects on job satisfaction and employee work engagement. A positive perception about servant leadership means that employees are satisfied at work and subordinates will remain engaged at workplace (Gui et al., 2021). Therefore, the current study focuses on work engagement and job satisfaction as the potential work outcomes of servant leadership and job crafting. Therefore, the overall aim of the current study is to address how servant leadership and work outcome relationships are mediated by crafting behaviours and, additionally, how conscientiousness moderates the link between servant leadership and crafting behaviours.

To achieve this aim, a questionnaire survey was conducted among hotel employees in Pakistan. In recent years, we have witnessed a boom in the hospitality industry of Pakistan (Khalil et al., 2021) that could be termed as highly productive, but understanding the experiences of employees within the hospitality industry has particularly remained neglected. The current study brings together servant leadership, job crafting, and personality trait literature to contribute to the existing body of knowledge in two ways. First, it uncovers whether servant leadership is significantly related to job crafting behaviours and how personality traits, such as conscientiousness, interact with this relationship. Second, the current study examines how the link between servant leadership and work outcomes is mediated by crafting behaviours. An understanding of these relationships and its consequences has several implications that we have discussed later in this study

Literature Review

Job Crafting

Employees attempt to alter the relational boundaries, the cognitive task boundaries, and the task boundaries (Supriyanto et al., 2020; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001) by adopting crafting strategies. Petrou et al. (Petrou et al., 2012) used the job demands-resources (JD-R) model as a theoretical framework to examine job crafting behaviours and strategies. The JD-R model categorises a job into job demands (i.e. demanding psychological and physical effort) and job resources (i.e. work characteristics that can reduce the costs of the demands and are functional for achieving work goals). Furthermore, in the JD-R model, resources can be seen as tools for motivating employees; demands, on the other hand, increase motivation if employees perceive them as a challenge (Demerouti et al., 2001; Prieto et al., 2008). Building on this stream of literature, Petrou et al. (Petrou et al., 2018) referred to the crafting strategies as self-initiated employee behaviour that aims to seek challenges (for instance, requesting for more responsibilities), seek resources (for instance, requesting supervisor or co-workers for advice), and reduce demands (for instance, reducing the physical, psychological, or emotional aspects of a job). Job crafting behaviours, in this sense, are the different reactions that employees adopt for dealing with ‘situations’, which arise consistently at workplaces.

Servant Leadership and Job Crafting

Servant leadership has received extensive coverage in academic research such as employee behaviour (Khan et al., 2021; Neubert et al., 2008), organisational commitment (Chinomona et al., 2013), teams’ performance (Song et al., 2015), and service quality (Qiu et al., 2020). Furthermore, servant leadership has been linked to the reduction of stress (Dooley et al., 2020), an employee’s decision to stay in the job (Jaramillo et al., 2009). A common theme among these studies is the suggestion that adequate servant leadership incudes the workers’ guidance and help for managing the demands and responsibilities of a job. In this sense, leaders can be seen as messengers that deliver positive messages for motivating and improving an employee’s self-efficacy and self-esteem (Qiu et al., 2020). Leaders/supervisors also act as a liaison between workers and the management by introducing an organisation’s work ethics to the new employees and to help them to settle in the new situation (Khan et al., 2021; McCarthy, 2003). Servant leadership within the organisational field does not just facilitate a ‘new situation’, per se, but also triggers a response from employees. When a new situation, in our case servant leadership, becomes unavoidable for employees and seeks ways to adjust to the new situation, workers do not ‘adjust’ or ‘fail to adjust’ by default to the support workers receive from leaders; in fact, Oreg et al. (Oreg et al., 2011) argued that employees’ responses to new situation vary depending upon a range of voluntary behaviours. The current study looks at job crafting behaviours as a voluntary behaviour that is triggered by the quality of the servant leadership.

Leana et al. (Leana et al., 2009) argued that motivating factors, for instance, job autonomy, leads employees to craft jobs but also when employees face ambiguous and uncertain situations at work (Grant & Parker, 2009; Supriyanto et al., 2020) or when the work environment is not ideal (Frese & Fay, 2001). Therefore, one can expect that job crafting is not only a consequence of a higher level of servant leadership (seeking resources and challenges) that employees receive but also when the perceived servant leadership is low (reducing demand). The current study therefore formulates:

Hypothesis 1: Seeking resources and challenges positively regresses servant leadership, while reducing demands negatively regresses on servant leadership.

Conscientiousness, Servant Leadership, and Job Crafting

Workers react to servant leadership on the basis of its perceived value (Jaramillo et al., 2009) and worker’s ability to create meaning (Dooley et al., 2020; Guillaume et al., 2013). Conscientiousness, among others, is a desirable and highly significant trait of the Big Five personality model (Gellatly, 1996). Prior research about conscientiousness clearly explains a distinction between high and low levels of conscientiousness in employees (Abbas & Raja, 2019). Employees with high conscientiousness are termed as disciplined, ambitious, methodical, and exacting, whereas employees that are less conscientious can be considered as disorganised, lazy, imprecise, and impetuous (Gellatly, 1996). Through conscientiousness, we can explore and understand how servant leadership is perceived by employees with varying levels of personalities.

Prior studies suggest that a high level of conscientiousness is associated with job outcomes (Abbas & Raja, 2019) and goal orientation (Colquitt & Simmering, 1998) and achievement motivation relationship (Barrick & Mount, 1993; Topino et al., 2021), and it also relates to problem-focused, engagement-focused, task-focused coping mechanisms (Brebner, 2001; Carver & Connor-Smith, 2010). Furthermore, highly conscientious employees are active in exploring different options to complete assigned work (Hochwarter et al., 2000) and to achieve set objectives (Topino et al., 2021). Employees with high conscientiousness embrace servant leadership as such employee’s primary objective is to grow and develop. Therefore, when servant leadership is clear, understandable, and timely, it motivates employees to embrace this new situation, holds value for them (Gui et al., 2021; Liberman et al., 1999), and initiates job crafting behaviours among employees. In this sense, employees perceive leader’s support as highly significant for achieving personal goals (Hochwarter et al., 2000; Khan et al., 2021). When employees display job crafting behaviours, for instance, seeking resources, it may result in different outcomes depending on varying personalities. For highly conscientious employees, seeking resources may act as a tool for adapting to the new situation. When servant leadership is high, highly conscientious employees are more motivated to attain growth by displaying specific actions that help in adjusting to the new situation. For instance, through seeking resources, employees strive for available opportunities such as learning and development and to utilise these resources; through challenges, employees may feel highly competent and work at full potential; and through reducing demands, employees may attempt to reduce interferences, which may stop employees from achieving ideal outcomes. The current study also assumes that servant leadership and job crafting relationship will be weaker among low conscientious employees. Hence, the current study hypothesises that:

Hypothesis 2a: High conscientiousness will strengthen the positive relationship between servant leadership and seeking resources.

Hypothesis 2b: High conscientiousness will strengthen the positive relationship between servant leadership and seeking challenges.

Hypothesis 2c: High conscientiousness will strengthen the negative relationship between servant leadership and reducing demand.

Job Crafting and Work Outcomes

Prior studies suggest that work engagement is high when employees are fulfilling, positive, exhibit motivation and high levels of energy during work, and are highly dedicated towards work (Fachrunnisa et al., 2020; Schaufeli et al., 2006). Work engagement is further categorised into three aspects, namely, vigour (being highly energetic even in difficult situations), dedication (highly involved in work, enthusiastic, and feel a sense of pride and inspiration), and absorption (feeling happy at what employees do) (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Job satisfaction refers to a feeling of enjoyment or fulfilment that an employee derives from the job (Guillaume et al., 2013; Topino et al., 2021; Viñas-Bardolet et al., 2020). Prior studies suggest that cognitive (evaluating one’s job), affective (emotions), and behavioural components are used to measure job satisfaction (Thompson & Phua, 2012). The current study critically examines the relationship between servant leadership with work outcomes, in this case job satisfaction and work engagement, through the lens of job crafting behaviours.

Seeking Resources

Petrou et al. (Petrou et al., 2012) argued that seeking resources is a strategy where employees seek learning opportunities or ask colleagues for feedback or advice on the work that employee performs. Via seeking resources, workers attempt to increase or build new resources to achieve set targets and goals (Demerouti et al., 2001), an enhancement of work participation, performance, and satisfaction (Bakker et al., 2004). In the presence of leader’s support, job resources can be helpful because it helps employees to adjust to the new situation (Petrou et al., 2018) and cope with uncertainty (Robinson & Griffiths, 2005). In this sense, the current study attempts to explain an observed relationship between a servant leadership and work outcomes (i.e. job satisfaction and work engagement) via the inclusion of seeking resources; thus, this becomes a mediator variable of the current study.

Hypothesis 3: Job satisfaction and employee work engagement positively regress on seeking resources.

Hypothesis 4: The link between servant leadership with job satisfaction and employee work engagement is mediated by seeking resources.

Seeking Challenges

Seeking challenges is self-initiated voluntary behaviour at work such as looking for more responsibilities or seeking new tasks once the work is finished (Petrou et al., 2012). In this sense, employees faced with challenge stressors display an increase level of motivation, positive attitudes, and emotions (Podsakoff et al., 2007). When employees focus on seeking challenges and responsibilities at work, this in turn improves employee’s participation at work (Fachrunnisa et al., 2019; Petrou et al., 2018) and, consequently, leads to employee satisfaction (Mofakhami, 2022). This is in line with social learning theory (Bandura, 1986) and with incremental approaches to servant leadership (Jaramillo et al., 2009; Qiu et al., 2020), where adjustment to new situations is facilitated by attaining expertise to overcome complex challenges. Via seeking challenges, these mastery experiences of employees enhance readiness to embrace the support offered by the leaders, and in return, it motivates subordinates, and the performance of employees is increased during work.

Hypothesis 5: Job satisfaction and employee work engagement positively regress on seeking challenges.

Hypothesis 6: The link between servant leadership with job satisfaction and employee work engagement is mediated by seeking challenges.

Reducing Demands

Reducing demands is primarily undesirable crafting strategies employed by the job crafters that may have negative implications. These types of behaviours are targeted towards minimising the physical, emotional, mental, or demanding aspects of employee work (Petrou et al., 2012). A reducing demands strategy can be termed as a task avoidance mechanism, which can also be seen as a withdrawal-oriented coping response (Amiot et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2021). Such responses are less effective in coping with new situations (servant leadership) and mainly involve an inflexible, negative, and disengaging approach in these situations (Parker & Endler, 1996). Reducing job demands is directly related to low motivation and can be seen as an unsuccessful strategy (Petrou et al., 2018) to adapt to the support offered by the leaders. In this sense, employees with reduced demands also reduce challenges at work and are less prepared to respond to new situations. As a consequence, it will also reduce workers work engagement and feel less satisfied at work. It is hypothesised that:

Hypothesis 7: Job satisfaction and employee work engagement negatively regress on reducing demands.

Hypothesis 8: The link between servant leadership with job satisfaction and employee work engagement is mediated by reducing demand.

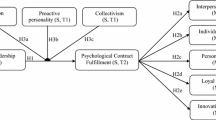

To summarise, Fig. 1 presents the key variables of the hypothesised model and the interconnectedness among the key constructs of the current study.

Method

Participants and Data Collection

The current study adopts a quantitative research approach where data was administered through survey questionnaires. The current study adopted purposive sampling method that allowed us to set parameters required for this study and select hotel employees working in the Galiyat region and the Naran valley of Pakistan. For identifying the minimum sample size, especially when dealing with latent constructs and structure equation models, it is recommended to adopt a sampling procedure that considers the manifest items as being a direct measure of latent construct (Khalil et al., 2021; Nunnally, 1978). The Nunnally (Nunnally, 1978) sample size criterion argues about the 1:10 ratio of manifest items. In other words, 10 cases are selected for each manifest item used in the model. The current study has a total of 34 manifest items nested in 7 latent constructs. Using this approach, the current study required a minimum sample size of (34 × 10) 340. To account for required sample size, outliers, missing information, and unreturned questionnaires, an invitation to participate in the survey was sent to 475 hotel employees. The survey was administered in person and introduced to the respondents through meetings. Three hundred ninety-six respondents completed the questionnaire survey with overall response rate of 83%. Fourteen questionnaires were removed due to outlier and missing data issues, resulting into 382 useable questionnaires. The average age of respondents was 21.6 years with a standard deviation of 2.11. Respondent’s job experience of the current study averaged at 4.4 years with a standard deviation of 2.94. Furthermore, 9.4% of the respondents were female. On average, 17.5% worked primarily in administrative positions with no interaction with customers, and 82.5% worked in customer support positions that required daily dealing with customers.

Measures

The researchers of the current study measured all constructs (reflective) with a response format of a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree to strongly agree). To measure servant leadership, the current study adapted a seven-item scale based on Liden et al. (Liden et al., 2015). We measured job crafting with its three dimensions (i.e. seeking resources, seeking challenges, and reducing demands) of general-level job crafting based on the scale developed by Petrou et al. (Petrou et al., 2012). Seeking resources was measured by four items, seeking challenges by three items, and reducing demand by four items.

The current study adopted a nine-item scale from Schaufeli et al. (Schaufeli et al., 2006) to measure work engagement. Seashore et al.’s (Seashore et al., 1983) scale with three items was used to measure job satisfaction. Furthermore, the current study adapted a four-item scale of conscientiousness from the international personality item pool (IPIP) developed by Donnellan et al. (Donnellan et al., 2006).

Job crafting behaviours may vary across gender, experience, age, and education when exposed to servant leadership. Therefore, the final analysis model included gender, experience, education, and age as control variables.

Analysis and Results

Assessing the Measurement Model

The overall emphasis of the current study lies in the understanding of causality of hypothesised relationships thus can be termed as predictive-oriented study. Sarstedt et al. (Sarstedt et al., 2022) recommend the use partial least square (PLS) method for analysing causal predictive-oriented structure equation models. Because all constructs are reflective, consistent PLS (PLSc) was used for the measurement model assessment. When dealing with reflective constructs, it is recommended to use PLSc instead of standard PLS as it provides more consistent results (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015).

The current study measurement model assessment builds on the typical reliability and validity criteria which is recommended for measuring reflective models in the existing studies (Becker et al., 2018; Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015).

The results in Table 1 show that the loadings of all reflective indicators are above the threshold level of 0.708 (Hair et al., 2019) except SL4, SR5, WE7, and WE8, which were thus deleted. All constructs of the current study model yielded satisfactory levels of convergent validity and internal consistency. For instance, servant leadership exhibited a convergent validity of (AVE = 0.659), and internal consistency reliability was (composite reliability CR = 0.920; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.920; rho_A = 0.923), although a value between 0.7 and 0.9 is recommended for internal consistency reliability (Hair et al., 2019).

Heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) criterion was used by previous studies to determine discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015). Kline (Kline, 2011) argues that discriminant validity is evident when HTMT values are less than 0.85. As can be seen in Table 2, the HTMT values for SL, SR, SC, RD, JS, and WE are well below the conservative threshold of the HTMT0.85 and thus provide support for discriminant validity for the measurement model of the current study (Henseler et al., 2015; Kline, 2011).

Mediation Analysis

The current study investigated the link between servant leadership and work outcomes through the underlining role of job crafting behaviours by assessing its indirect effects (Table 3). The current study adopted Hayes and Preacher (Hayes & Preacher, 2014) method and used a bootstrapping procedure (5000 samples) to produce distinctive indirect effects and corresponding standard errors. As shown in Table 3, the current study hypotheses H4a, H4b, H6a, H6b, H8a, and H8b were statistically significant where the corresponding confidence intervals of the relationships did not contain a zero value (Nitzl et al., 2016), which depicts support for the mediation effects of job crafting.

Assessing the Structural Model

In the current study, a bootstrapping procedure was used and ran a consistent PLS bootstrapping with 5000 resamples to test the proposed hypothesis. To check collinearity issues among the constructs, the values of variance inflation factor (VIF) were used (see Table 6, Appendix 1). We did not find any collinearity issues as all VIF values were less than the threshold of 3, suggested by Hair et al. (Hair et al., 2019). The current study examined in-sample predictive power by assessing the R2 value of the endogenous constructs. The endogenous constructs of this study model show a moderate to weak predictive power. The current study further assessed the effect size (f2) to examine how the exclusion of a specific predictor construct will affect the R2 of endogenous constructs. According to Hair et al. (Hair et al., 2019), the f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are considered small, medium, and large effects, respectively.

As can be seen in Table 4, seeking challenges has a medium effect on job satisfaction, whereas all other predictors had a small effect on endogenous constructs. Consequently, Q2 through a blindfolding procedure was analysed to assess the model’s predictive accuracy. A small difference between the original and the predicted values translates into a higher Q2 value and thus indicates a high predictive accuracy. The Q2 values of the predictor constructs were higher than zero but less than 0.25, which show a small predictive accuracy (Hair et al., 2019). The R2 depicts in-sample predictive power, but it is recommended to assess out-of-sample predictive power through PLSpredict. We followed Shmueli et al. (Shmueli et al., 2019) procedure for assessing out-of-sample predictive power. All measures of endogenous constructs had a Q2 > 0 (see Table 7, Appendix 2). Consequently, the current study compared the values of the PLS path model (PLS) MAE to linear regression model’s (LM) mean absolute error (MAE) values. In most cases, the LM values were greater than the PLS value (Hair et al., 2019), thus suggesting a moderate out-of-sample predictive power for the model.

Moderation

The moderating effect of conscientiousness was assessed by setting indicator weighting to the ‘mode A’, calculation method to ‘product indicator approach’, and product term generation to ‘standardised’ to generate the interaction term (Hair et al., 2019).

The interaction term (CONS*SL) was used during the bootstrapping procedure to analyse the moderation effects. Table 5 presents the three interactions and its results that we proposed earlier in this study. The results of the current study reveal that a higher level of employee conscientiousness strengthens the relationship between servant leadership and (a) seeking resources and (b) seeking challenges (Fig. 2). The moderation effect of conscientiousness regarding the relationship of servant leadership and reducing demands came out statistically insignificant.

Discussion

The current study hypothesised that (H1a and H1b) seeking resources and challenges positively regresses servant leadership, while reducing demands negatively regresses on servant leadership. Furthermore, work engagement and job satisfaction will positively regress on seeking resources (H3a and H3b) and seeking challenges (H5a and H5b), whereas these outcomes were expected to negatively regress on reducing demands (H7a and H7b). Furthermore, the current study hypothesised (H4a, H4b, H6a, H6b, H8a, and H8b) that job crafting behaviours will mediate links between servant leadership and the work outcomes. In addition, we expected the servant leadership to influence job crafting behaviours when we consider personality traits such as conscientiousness (H2a, H2b, and H2c). The current study expected that servant leadership would have a positive relationship with job crafting when employee conscientiousness is high.

While looking into how employees adjust to perceived servant leadership through job crafting strategies, the findings of the current study suggest that job satisfaction and work engagement are positively predicted by seeking resources and seeking challenges. These results are in line with the theory of the conservation of resources, which suggest that seeking resources is an attempt to expand an individual’s resources and, in return, motivates employees during work (Hobfoll, 2001; Tims et al., 2013). The findings of the current study are also consistent with the De Clercq et al. (Clercq et al., 2014) and Guillaume et al. (Guillaume et al., 2013) studies, suggesting that highly motivated employees are more engaged and satisfied when exposed to servant leadership. Reducing demands acts as a coping mechanism, based on emotions, which is primarily ineffective when employees receive leader support. Consequently, employees with a tendency of not utilising a reducing demands strategy are highly satisfied at work and show increased levels of participation during work. This is in line with the current study findings, which revealed that a higher level of reducing demands predicts a lower level of job satisfaction and work engagement. Job crafting behaviours partially mediate the relationship between servant leadership and work outcomes (job satisfaction and work engagement). Based on the findings of the current study, we argue that employees seeking resources and challenges strategies are highly significant for employees’ job satisfactions and for increased participation (work engagement) when exposed to servant leadership, whereas reducing demands can be seen as a potentially unsuccessful employee strategy when servant leadership is high.

As expected, the findings of the current study revealed that highly conscientious employees sought more resources and challenges when servant leadership was high. The level of conscientiousness varies among individuals and triggers different response behaviours when motivation is high (Parker & Griffin, 2011). The findings of the current study were consistent with Parker and Griffin (Parker & Griffin, 2011) study suggesting that job crafting acts as a significant motivation tool for highly conscientious individuals who are enthused by the servant leadership.

The interaction of conscientiousness concerning the relationship between servant leadership and reducing demands was statistically insignificant. This may have occurred since reducing demand behaviours is triggered by the need to cope with work stress and, therefore, can be explained by mental demands and the communication complexities of servant leadership and other variables that the current study did not hypothesise in the current study.

Conclusion

The current study attempted to examine how employees use crafting strategies (i.e. seeking resources, seeking challenges, and reducing demands) when exposed to servant leadership. Inspired by the personality trait theory with an emphasis on conscientiousness, we proposed that employees with high or low conscientiousness react differently to servant leadership by adopting varying job crafting strategies, which further promote or obstruct work outcomes (i.e. engagement and job satisfaction). The findings of the current study reveal that both work outcomes positively regress on seeking resources and challenges and negatively regresses on reducing demand. The link between servant leadership and work outcomes is mediated by the job crafting behaviours. Evidently, conscientiousness moderates the link between servant leadership, seeking resources, and seeking challenges. The findings of the current study entail theoretical and managerial implications that are discussed below.

Theoretical Implications

The current study contributes to the existing body of knowledge in several ways. First, the current study builds on servant leadership theory as it plays a key role during job crafting behaviours targeted at employee participation and satisfaction. Second, using the personality trait theory, by focusing on conscientiousness, the current study attempted to explain how different levels of motivation (i.e. high vs. low perceived servant leadership) lead to the adaption of varying job crafting behaviours. In this sense, the findings of the current study build upon prior theoretical concepts and findings to explain how optimal and suboptimal servant leadership triggers varying job crafting behaviours. Finally, the current study illustrates how measurable changes in crafting behaviours are produced by servant leadership, and how work engagement and job satisfaction are affected in the presence of job crafting behaviours. In retrospect, the current study empirically integrated three streams of literature, namely, personality trait (i.e. conscientiousness), job crafting, and servant leadership, which have been mainly addressed independently.

Managerial Implications

From a managerial perspective, prior studies suggest that effective and well-communicated servant leadership triggers a positive response from employees. As evident from the findings of the current study, servant leadership positively predicts job satisfaction and work engagement and has a negative relationship with unfavourable crafting behaviours (i.e. reducing demands). When leaders adopt servant leadership, it can create favourable employee outcomes; therefore, the current study recommends managers to place special emphasis on servant leadership to construct positive job crafting behaviours. With the leader’s support, employees tend to seek challenges and resources. Such positive crafting behaviours lead to a higher level of job satisfaction, and they will remain highly engaged at work and thus can possibly result in several positive organisational outcomes (i.e. high efficiency, low employee turn-over, positivity at workplace, and better work environment). For manager and leaders, it is also important to identify employee with low or high conscientiousness levels. As evident from our study, high level of conscientiousness strengthens the positive crafting behaviours and servant leadership relationships. Managers thus need to create and sustain an environment that promotes high conscientiousness of employees.

Limitations

The limitations of the current study were geographical, contextual, and theoretical in nature. The data were collected from hotel employees in two regions of Pakistan (i.e. the Naran valley and the Galiyat region); therefore, this may lead to generalisability issue. The current study examined the relationships between servant leadership, personality traits, job crafting, and work outcomes from the context of hospitality, which may not entirely translate into other sectors. Furthermore, the lower predictive power of the constructs can also be attributed as a minor limitation of the current study. The measures of the model depict low to moderate predictive power (i.e. both in sample (R2) and out of sample (PLSpredict)) predictive relevance (Q2) and effect size (f2). A moderate to strong predictive power would be ideal, but low to moderate predictive power and relevance are widely acceptable among academic researchers (Hair et al., 2019); therefore, it should not be a considered as a major concern. The results of the current study suggest that conscientiousness plays a key role during job crafting (i.e. seeking challenges and resources) when exposed to servant leadership. However, the interaction between servant leadership and conscientiousness did not moderate reducing demands behaviours. This assumption needs to be further tested empirically.

Future Research

Based on the findings and limitations of the current study, we recommend some research ideas that not only will further the findings of our study but will also substantially add to the body of knowledge. Our findings highlight some key mechanisms of improving job satisfaction and employee engagement but certainly lack generalisability. It would be interesting to compare findings obtained from other sectors, for instance, banking, education, and the public offices of different countries. The current study investigated personality traits through conscientiousness and did not include other personality traits such as openness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism, due to limited time and resources. It would be interesting to explore these personality traits in relation to job crafting behaviours and work outcomes in future studies. Job crafting plays a key role in an organisational setup; thus, it can be conceptualised to varying outcome variables such as innovation, creativity, and sustainability outcomes. Similarly, job crating behaviours can be further studied as an outcome/intervening variable of several emerging predictor variables, for instance, green human resource management, human capital sustainability leadership, and high-performance work systems.

References

Abbas, M., & Raja, U. (2019). Challenge-hindrance stressors and job outcomes: The moderating role of conscientiousness. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(2), 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9535-z

Amiot, C. E., Terry, D. J., Jimmieson, N. L., & Callan, V. J. (2006). A longitudinal investigation of coping processes during a merger: Implications for job satisfaction and organizational identification. Journal of Management, 32(4), 552–574. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206306287542

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20004

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Psychology Press.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1993). Autonomy as a moderator of the relationships between the big five personality dimensions and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.111

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Strauss, J. P. (1993). Conscientiousness and performance of Sales representatives: Test of the mediating effects of goal setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(5), 715–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.5.715

Becker, J.-M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2018). Estimating moderating effects in PLS-SEM and PLSc-SEM: Interaction term generation* data treatment. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 2(2), 1–21.

Brebner, J. (2001). Personality and stress coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(3), 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00138-0

Carver, C. S., & Connor-Smith, J. (2010). Personality and coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100352

Chinomona, R., Mashiloane, M., & Pooe, D. (2013). The influence of servant leadership on employee trust in a leader and commitment to the organization. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(14), 405–405. https://doi.org/10.36941/mjss

Clercq, D., Bouckenooghe, D., Raja, U., & Matsyborska, G. (2014). Servant leadership and work engagement: The contingency effects of leader–follower social capital. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 25(2), 183–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.21185

Colquitt, J., & Simmering, M. (1998). Conscientiousness, goal orientation, and motivation to learn during the learning process: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(4), 654–665. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.4.654

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00174

Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The Mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.18.2.192

Dooley, L. M., Alizadeh, A., Qiu, S., & Wu, H. (2020). Does servant leadership moderate the relationship between job stress and physical health? Sustainability, 12(16), 6591. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166591

Eby, L. T. (1997). Alternative forms of mentoring in changing organizational environments: A conceptual extension of the mentoring literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51(1), 125–144. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1594

Fachrunnisa, O., Siswanti, Y., Qadri, E., Mustofa, Z., & Harjito, D. A. (2019). Empowering leadership and individual readiness to change: The role of people dimension and work method. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 10(4), 1515–1535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-019-00618-z

Frese, M., & Fay, D. (2001). 4. Personal initiative: An active performance concept for work in the 21st century. Research in Organizational Behavior, 23, 133–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(01)23005-6

Gellatly, I. R. (1996). Conscientiousness and task performance: Test of cognitive process model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(5), 474–482. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.5.474

Grant, A. M., & Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 317–375. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903047327

Griffin, M. A., Neal, A., & Parker, S. K. (2007). A new model of work role performance: Positive behavior in uncertain and interdependent contexts. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24634438

Gui, C., Zhang, P., Zou, R., & Ouyang, X. (2021). Servant leadership in hospitality: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(4), 438–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2021.1852641

Guillaume, O., Honeycutt, A., & Savage-Austin, A. R. (2013). The impact of servant leadership on job satisfaction. Journal of Business and Economics, 4(5), 444–448.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hochwarter, W., Witt, L., & Kacmar, K. (2000). Perceptions of organizational politics as a moderator of the relationship between conscientiousness and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 472–478. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.472

Jaramillo, F., Grisaffe, D. B., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2009). Examining the impact of servant leadership on salesperson’s turnover intention. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 29(4), 351–365. https://doi.org/10.2753/PSS0885-3134290404

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Pucik, V., & Welbourne, T. M. (1999). Managerial coping with organizational change: A dispositional perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.1.107

Khalil, S. H., Shah, S. M. A., & Khalil, S. M. (2021). Sustaining work outcomes through human capital sustainability leadership: Knowledge sharing behaviour as an underlining mechanism. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 42(7), 1119–1135. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-02-2021-0051

Khan, M. M., Mubarik, M. S., Islam, T., Rehman, A., Ahmed, S. S., Khan, E., & Sohail, F. (2021). How servant leadership triggers innovative work behavior: Exploring the sequential mediating role of psychological empowerment and job crafting. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(4), 1037–1055. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-09-2020-0367

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

Leana, C., Appelbaum, E., & Shevchuk, I. (2009). Work process and quality of care in early childhood education: The role of job crafting. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6), 1169–1192. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.47084651

Liberman, N., Idson, L., Camacho, C., & Higgins, E. (1999). Promotion and prevention choices between stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1135–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1135

Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., Meuser, J. D., Hu, J., Wu, J., & Liao, C. (2015). Servant leadership: Validation of a short form of the SL-28. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.12.002

Liu, F., Qin, W., Liu, X., Li, J., & Sun, L. (2022). Enabling and burdening: The double-edged sword of conscientiousness. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111216

McCarthy, M. L. (2003). . [Doctoral dissertation,], Memorial University of Newfoundland .

Mofakhami, M. (2022). Is innovation good for European workers? Beyond the employment destruction/creation effects, technology adoption affects the working conditions of European workers. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 13(3), 2386–2430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00819-5

Neubert, M. J., Kacmar, K. M., Carlson, D. S., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2008). Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on employee behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1220. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012695

Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-07-2015-0302

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw.

Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(4), 461–524. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886310396550

Parker, J. D. A., & Endler, N. S. (1996). Coping and defense: A historical overview. In M. Zeidner & N. S. Endler (Eds.), Handbook of Coping: Theory, Research, Applications (pp. 3–23). John Wiley & Sons.

Parker, S. K., & Griffin, M. A. (2011). Understanding active psychological states: Embedding engagement in a wider nomological net and closer attention to performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 20(1), 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2010.532869

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). (2014). European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Fachrunnisa, O., Adhiatma, A., & Tjahjono, H. K. (2020). Cognitive collective engagement: Relating knowledge-based practices and innovation performance. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(2), 743–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-018-0572-7

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., Peeters, M. C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hetland, J. (2012). Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(8), 1120–1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1783

Petrou, P., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2018). Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. Journal of Management, 44(5), 1766–1792. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315624961

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438

Prieto, L. L., Soria, M. S., Martínez, I. M., & Schaufeli, W. (2008). Extension of the job demands-resources model in the prediction of burnout and engagement among teachers over time. Psicothema, 20(3), 354–360.

Qiu, S., Dooley, L. M., & Xie, L. (2020). How servant leadership and self-efficacy interact to affect service quality in the hospitality industry: A polynomial regression with response surface analysis. Tourism Management, 78, 104051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104051

Roberts, B. W., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., & Goldberg, L. R. (2005). The structure of conscientiousness: An empirical investigation based on seven major personality questionnaires. Personnel Psychology, 58(1), 103–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00301.x

Robinson, O., & Griffiths, A. (2005). Coping with the stress of transformational change in a government department. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 41(2), 204–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886304270336

Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Pick, M., Liengaard, B. D., Radomir, L., & Ringle, C. M. (2022). Progress in partial least squares structural equation modeling use in marketing research in the last decade. Psychology & Marketing, 39(5), 1035–1064. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21640

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Seashore, S. E., Lawler III, E. E., Mirvis, P. H., & Cammann, C. E. (1983). Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Shmueli, G., Sarstedt, M., Hair, J. F., Cheah, J. H., Ting, H., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing, 53(11), 2322–2347. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2019-0189

Song, C., Park, K. R., & Kang, S.-W. (2015). Servant leadership and team performance: The mediating role of knowledge-sharing climate. Social Behavior and Personality, 43(10), 1749–1760. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.10.1749

Supriyanto, A. S., Sujianto, A. E., & Ekowati, V. M. (2020). Factors affecting innovative work behavior: Mediating role of knowledge sharing and job crafting. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(11), 999–1007. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no11.999

Thompson, E. R., & Phua, F. T. T. (2012). A brief index of affective job satisfaction. Group & Organization Management, 37(3), 275–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601111434201

Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2013). The impact of job crafting on job demands, job resources, and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(2), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032141

Topino, E., Fabio, A. D., Palazzeschi, L., & Gori, A. (2021). Personality traits, workers’ age, and job satisfaction: The moderated effect of conscientiousness. PLoS ONE, 16(7), e0252275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252275

Viñas-Bardolet, C., Torrent-Sellens, J., & Guillen-Royo, M. (2020). Knowledge workers and job satisfaction: Evidence from Europe. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11(1), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-018-0541-1

Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2001.4378011

Yukl, G. (2001). Leadership in organizations (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalil, S.H., Shah, S.M.A. & Khalil, S.M. Servant Leadership, Job Crafting Behaviours, and Work Outcomes: Does Employee Conscientiousness Matters?. J Knowl Econ 15, 2607–2627 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01290-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01290-0