Abstract

Background

Retroperitoneal infantile hemangioma (RIH), a type of primary retroperitoneal tumors, are exceptionally rare in clinical practice. Infantile hemangiomas typically manifest on the skin’s surface. RIHs are exceptionally rare and typically small. In adults, these tumors often manifest without specific clinical symptoms or detectable signs for a definitive diagnosis. This case report details a patient diagnosed with RIH. We recommend complete excision of the tumor after a comprehensive evaluation, followed by postoperative pathology, to achieve a conclusive diagnosis. We believe that managing critical retroperitoneal structures and vessels intraoperatively presents a significant challenge for all procedures involving primary retroperitoneal tumors.

Case summary

A 47-year-old male was diagnosed with gallstones and underwent surgery 3 months ago at other institution for unexplained nausea and vomiting. Follow-up imaging 2 months after surgery revealed a retroperitoneal mass below the left renal pole. Upon presentation to our hospital, the patient continued to experience intermittent nausea and vomiting, with no other significant symptoms or signs. Considering the patient’s 8-year history of hypertension, a paraganglioma was initially suspected. We performed the laparoscopic mass resection after a detailed assessment. However, postoperative pathology revealed it a capillary hemangioma (old term)/infantile hemangioma.

Conclusion

RIHs are exceedingly rare benign tumor. The possibility of malignancy should be ruled out, and surgical resection is recommended following a thorough evaluation, with the diagnosis confirmed through pathological examination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Generally, a mass is considered a primary retroperitoneal tumor (PRT) if it originates in the soft tissue, lymphatics, or nervous tissue of the retroperitoneal space, rather than being a solid organ [1]. Secondary lesions, cancer metastases and lymph node enlargement were excluded. Vascular anomalies may occur at various ages and in different organs, including the retroperitoneal region. According to the 2018 International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification overview table, vascular anomalies are broadly classified into “vascular tumors”, involving abnormal proliferation of vascular endothelial cell, and “vascular malformations”, which are structural vascular abnormalities [2]. Vascular tumors can further be categorized into three groups: benign (e.g., infantile hemangioma, mentioned subsequently), locally aggressive or borderline (e.g., Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma), and malignant (e.g., angiosarcoma) [3]. Vascular tumors are uncommon in PRT, and the diagnosis becomes challenging when vascular tumors, along with other forms of tumors, are present in the retroperitoneal space rather than within an organ [4]. Infantile hemangiomas typically manifest on the skin’s surface. Superficial IHs, located in the upper dermis, appear as raised red papules, nodules, or plaques, while deep IHs extending into adipose tissue present as indistinctly bordered blue tumors [5]. Retroperitoneal infantile hemangioma (RIH) is extremely rare, with only four cases reported in English literature over the past two decades. This article presents a rare case of RIH. Additionally, we conduct a retrospective analysis of prior case reports and relevant literature, summarizing other lesions that require differentiation to enhance our understanding of this specific disease.

2 Case description

A 47-year-old male sought medical attention 3 months ago due to unexplained nausea and vomiting. He was diagnosed with gallstones and subsequently underwent cholecystectomy. A left retroperitoneal mass was discovered during a follow-up 2 months after gallstone surgery, leading the patient to seek care at our institution. Upon admission, the patient reported continued intermittent nausea and vomiting but denied experiencing chest tightness, chest pain, low back pain, as well as intestinal or urinary tract symptoms. The patient had no history of habitual drinking or smoking but had an 8-year history of hypertension and a 20-year history of hepatitis B. His mother was diagnosed with liver cirrhosis and hypertension. The results of laboratory and biochemical tests are presented in Table 1. Except for abnormal items and those of concern, all other items were within normal limits.

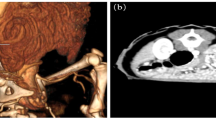

Computed tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) can clearly reveal certain tumor contents, providing valuable insights to help refine the differential diagnosis [6]. On contrast-enhanced abdominal CT, a soft-tissue density shadow with irregular morphology measuring 3.2 cm × 2.0 cm was identified below the left renal pole, anterior to the psoas major muscle (Fig. 1A). Significant localized enhancement was observed in the arterial phase, with persistent enhancement in the venous phase and reduced enhancement in the delayed phase (Fig. 1B). MRI revealed an oval-shaped abnormal signal at the same location, displaying low signal in the T1-weighted image, high signal in T2 (long T1 and long T2 signals), high signal in T2-weighted compression fat image, high signal in DWI, and an unchanged ADC value (Fig. 1C). No significant abnormal signals were observed in the liver, gallbladder, spleen, tail of the pancreatic body, or left adrenal gland, and no definite enlarged lymph nodes were found. However, the evidence alone was insufficient to clarify the nature of the tumor. Combining the imaging features of the tumor with the patient's extensive history of hypertension, we suspected a paraganglioma. Following the evaluation of the patient's indicators, we opted for laparoscopic tumor resection. The laparoscopic-assisted mass excision was irregularly shaped and wrapped in adipose tissue (Fig. 2A). A grey-brown nodule with a firm texture and a cross-sectional size of approximately 2.7 cm × 1.2 cm was observed (Fig. 2B). Postoperative pathology (Fig. 3) samples and immunohistochemistry suggested that this was a primary capillary hemangioma (old term)/infantile hemangioma.

A Abdominal CT scan reveals a soft tissue density shadow measuring approximately 3.2 cm × 2.0 cm below the left lower pole of the kidney, anterior to the psoas major muscle. B Enhanced abdominal CT shows localized significant enhancement in the arterial phase. C Abdominal MRI displays an abnormal elliptical signal. CT computerized tomography, MRI Magnetic Resonance Imaging

2.1 Postoperative pathology

CD56 (+), Syn (−), CgA (−), S-100 (−), CD34 (vascular+), CD31 (vascular+), CD163 (scattered+), AE1/3 (−), Vim (+), EMA (−), NSE (−), SMA (+), Ki-67 (about1%+), CK7 (−), HMB45 (−), Inhibinα (−), CD117 (scattered+).

3 Discussion

In the latest ISSVA classification, vascular anomalies encompass vascular tumors and vascular malformations [2]. However, most prior literature did not rigorously classify these lesions according to ISSVA, making challenges in literature search and clinical management. Historically, they were commonly labeled as “hemangiomas” or “angiomas,” inaccurately encompassing non-infantile hemangiomas and certain vascular malformations. For instance, phrases like “cavernous hemangiomas” or “venous hemangiomas” used in the literature actually denote venous malformations rather than vascular tumors. The infantile hemangiomas (IHs) discussed in this article, primarily situated in the dermis and displaying a bright red color, were formerly denoted as capillary hemangiomas [7]. The ISSVA classification is an internationally recognized standard for categorizing vascular malformations. Using consistent terminology helps ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment for patients, while also minimizing diagnostic errors and improving scholarly communication by reducing confusion caused by inconsistent terminology [8, 9].

IHs typically manifest on the body surface, representing the most prevalent benign tumors in infancy that generally do not necessitate specific management. However, depending on their growth site, certain IHs may pose significant potential risks [7]. Notably, RIHs are exceedingly uncommon, with only four cases documented in the English literature over the past two decades [10,11,12,13]. The onset of these IHs in adults occurs, on average, at 56 years of age, and the maximum observed diameter of the mass has not exceeded 3 cm in each patient (Table 2). Due to the limited physique in infant patients, even a small mass may have the potential to invade surrounding organs. IHs should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained lower gastrointestinal bleeding in neonates [12]. However, the retroperitoneal space is expansive in adults; thus, RIHs may not extensively involve surrounding organs, leading to a lack of significant symptoms. Moreover, many PRTs may remain asymptomatic in their early stages. Initial examinations often face challenges in associating an unidentified retroperitoneal mass with IHs based solely on patient symptoms and imaging. Complete excision of the mass is recommended, followed by postoperative pathology, to achieve a conclusive diagnosis. Moreover, surgical resection of all PRTs poses challenges due to the proximity of vital structures in the retroperitoneum and nearby blood vessels. These factors can impact local recurrence, postoperative outcomes, and long-term survival [14]. Therefore, a pathological biopsy becomes crucial for elucidating the nature of the mass. Aligning with insights from prior literature, it is crucial to distinguish RIHs from various other PRTs.

While the available laboratory evidence did not indicate catecholamine (CA) abnormalities, the patient’s enduring 8-year history of hypertension, the tumor’s location adjacent to the kidneys and urinary tract, and its distinctive imaging features led us to initially consider a paraganglioma (PGL). PGL originating outside the adrenal gland are uncommon catecholamine-secreting endocrine tumors. They are characterized by sudden or sustained hypertension, and excessive release of CA can induce severe cardiovascular manifestations, including Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, hypertensive crisis and acute myocardial infarction [15]. A pertinent family history of genetic disorders or PGL-related syndromes could assist in the diagnosis of PGL. The preferred test for identifying CA overdose is the 24-h urine or plasma free adrenaline test [16]. The imaging features include MRI with low or equal signal on T1-weighted imaging and high signal on T2-weighted imaging.

The diagnosis of postoperative pathology is also challenging due to certain similarities in the microscopic structure between IHs and anastomosing hemangiomas (AH). Montgomery and Epstein initially delineated this uncommon vascular tumor in 2009 [17]. Differing from IHs, AHs exhibit microscopic findings characterized by the occlusion of vascular channels, lined with a monolayer of occasionally pegged endothelial cells, interspersed with hyaline globules, and frequently associated with fibrin thrombi [18]. The primary involvement of AHs are within the genitourinary system, particularly demonstrating a predilection for the kidneys [19]. While AHs typically present as a substantial lesion, cystic formations may also be observed. According to previous literature, over 65% of cases were not exceed 3 cm in size, with a maximum of 14 cm [20]. The imaging characteristics, such as “well-defined, high or equal signal on T2-weighted imaging (T2 WI), equal signal on Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI), and a marked progressive pattern of enhancement, possibly vascular enhancement,” can provide indications suggestive of AH[20].

Moreover, we suggest considering Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) in the evaluation of suspected retroperitoneal vascular tumors in the future. KHE is a locally aggressive vascular tumor sharing histological morphology with Kaposi Sarcoma. Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon (KMP) occurs in some KHE patients, featuring profound and sustained thrombocytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, consumptive coagulopathy, and elevated D-dimer levels [3]. Some patients with Tufted angioma (TA) also present with KMP. Although approximately 70% of KHE cases appears on the body surface, nearly 20% manifest in deeper regions, including the retroperitoneum [21, 22]. In instances where patients with retroperitoneal tumors exhibit KMP, clinicians should consider the possibility of KHE/TA (Table 3). However, no cases of retroperitoneal TA have been reported. Due to the deep infiltrative nature of KHE, it may not be discernible on ultrasound, while MRI is recommended for a comprehensive evaluation. The typical presentation involves poorly defined borders, multiplanar involvement, diffuse enhancement, adjacent fat strands in atypical locations, isointensity on T1-weighted imaging relative to adjacent muscle, and high signal on T2-weighted imaging.

Oral propranolol is now the first-line conservative treatment for IH. Hemangioma shrinkage is rapidly observed with oral propranolol. A large cohort study showed an average response rate of 96–98% after 6 months of therapy [5]. However, detecting and accurately diagnosing internally situated IHs, can present challenges for clinicians. It may hinder the timely development of an appropriate conservative treatment plan.

We posit that RIH should be considered in the differential diagnosis for adults presenting with retroperitoneal nodular enhancement on CT scans, particularly when the nodules are less than 3 cm in size and lack other significant symptoms or associated laboratory abnormalities.

4 Conclusion

We provide a case of RIH. RIHs are exceedingly rare primary retroperitoneal tumors. Diagnosing them in the initial stage poses challenges with ancillary tests. Conservative approaches without a definitive diagnosis are not recommended due to its specific location and diagnostic challenges. Considering the symptoms, potential malignancy must be eliminated, and a definitive diagnosis should be established through surgical resection and comprehensive pathological examination following detailed evaluation.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Czeyda-Pommersheim F, Menias C, Boustani A, Revzin M. Diagnostic approach to primary retroperitoneal pathologies: what the radiologist needs to know. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46(3):1062–81.

Kunimoto K, Yamamoto Y, Jinnin M. ISSVA classification of vascular anomalies and molecular biology. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):2358.

ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies ©2018 International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. http://www.issva.org/classification. Accessed 12 Oct 2023.

Improta L, Tzanis D, Bouhadiba T, Abdelhafidh K, Bonvalot S. Overview of primary adult retroperitoneal tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46(9):1573–9.

Leaute-Labreze C, Harper JI, Hoeger PH. Infantile haemangioma. Lancet. 2017;390(10089):85–94.

Nishino M, Hayakawa K, Minami M, Yamamoto A, Ueda H, Takasu K. Primary retroperitoneal neoplasms: CT and MR imaging findings with anatomic and pathologic diagnostic clues. Radiographics. 2003;23(1):45–57.

Darrow DH, Greene AK, Mancini AJ, Nopper AJ, Neck S, Section On Dermatology SOO-H, Section On Plastic S. Diagnosis and management of infantile hemangioma. Pediatrics. 2015;136(4):e1060-1104.

Lin Q, Cai B, Shan X, Ni X, Chen X, Ke R, Wang B. Global research trends of infantile hemangioma: a bibliometric and visualization analysis from 2000 to 2022. Heliyon. 2023;9(11): e21300.

Steele L, Zbeidy S, Thomson J, Flohr C. How is the term haemangioma used in the literature? An evaluation against the revised ISSVA classification. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(5):628–33.

Vasudevan SA, Cumbie TA, Dishop MK, Nuchtern JG. Retroperitoneal hemangioma of infancy. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(1):e41-44.

Godar M, Yuan Q, Shakya R, Xia Y, Zhang P. Mixed capillary venous retroperitoneal hemangioma. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013: 258352.

Krick J, Riehle K, Chapman T, Chabra S. Recurrent bloody stools associated with visceral infantile haemangioma in a preterm twin girl. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11(1):bcr-2018.

Chen B, Wang H, Fu S, Zuo Y. Retroperitoneal capillary hemangioma: a case report and literature review. Asian J Surg. 2023;46(11):4881–2.

Xu YH, Guo KJ, Guo RX, Ge CL, Tian YL, He SG. Surgical management of 143 patients with adult primary retroperitoneal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(18):2619–21.

Yassan S, Falhammar H. Cardiovascular manifestations and complications of pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2435.

Jain A, Baracco R, Kapur G. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma-an update on diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35(4):581–94.

Montgomery E, Epstein JI. Anastomosing hemangioma of the genitourinary tract: a lesion mimicking angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(9):1364–9.

Torrence D, Antonescu CR. The genetics of vascular tumours: an update. Histopathology. 2022;80(1):19–32.

Zhao M, Li C, Zheng J, Sun K. Anastomosing hemangioma of the kidney: a case report of a rare subtype of hemangioma mimicking angiosarcoma and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(4):757–65.

Xue X, Song M, Xiao W, Chen F, Huang Q. Imaging findings of retroperitoneal anastomosing hemangioma: a case report and literature review. BMC Urol. 2022;22(1):77.

Yao W, Li KL, Qin ZP, Li K, Zheng JW, Fan XD, Ma L, Zhou DK, Liu XJ, Wei L, et al. Standards of care for Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon in China. World J Pediatr. 2021;17(2):123–30.

Ning J. A rare case of retroperitoneal kaposiform hemangioendothelioma with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Asian J Surg. 2023;46(4):1904–5.

Acknowledgements

There is no acknowledgment.

Funding

Special Fund for Clinical Research of Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (No. 320.6750.2022-25-11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Li P.Z., He S. and Pang Y.W. collected the data. Li P.Z. wrote the manuscript. Yan Y.J. and Shi J. contributed to manuscript preparation and revision. Duan J.Y. and Wu Y.B. contributed to data visualization and validation. Yang L.J. offered guidelines for the pathological diagnosis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dongzhimen Hospital, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine. The institutional ethics committee approved the acquisition of all samples and all methods conducted. Informed consent statement for case reporting and publishing was obtained from the participants and their families. The patient and their family provided consent for the publication of anonymized data in an open-access journal. All surgeries and experiments adhere to the relevant guidelines and regulations. All data have been anonymized.

Consent for publication

The patient has provided informed consent for her clinical, laboratory, and imaging data to be utilized for the purpose of medical research, including journal case publications. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., He, S., Wu, Y. et al. Retroperitoneal infantile hemangioma: a case report and literature review. Discov Onc 15, 373 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-024-01260-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-024-01260-1