Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the effects of two meditation-based programs, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) and Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT), in a brief and intensive format on various psychological variables in a group of healthy volunteer adults attending a retreat with a crossover design.

Method

Participants received both interventions in a random order over 7 days (MBSR-CCT, n = 25; CCT-MBSR, n = 24). Assessments were conducted at three different times: Day 1 (pre-program), Day 4 (after completing the first program and before starting the second program), and Day 7 (post-second program), with a follow-up assessment 3 months later.

Results

A significant time main effect was found for emotion regulation (p < 0.001; b = 0.49), self-compassion (p < 0.001; b = − 0.78), mindfulness (p < 0.001; b = − 1.06), low-arousal positive affect (p < 0.001; b = − 1.39), and high-arousal negative affect (p < 0.001; b = 1.82), with improvements in the expected directions observed in both groups. However, the combination of MBSR followed by CCT showed an advantage in some psychological outcomes following the retreat. The follow-up analysis revealed that some of the psychological benefits observed were retained after 3 months (e.g., emotional distress and regulation, self-compassion, and mindfulness), especially in the groups starting their training with MBSR followed by CCT.

Conclusions

These findings highlight the benefits of meditation-based interventions in a brief and intensive format for psychological functioning in healthy adults, providing novel results on the sequential and combined effects of MBSR and CCT, with implications for practice and interventions.

Pre-registration

The study was pre-registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05516355).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Intensive multi-day interventions, such as meditation retreats, have become increasingly popular as accessible ways to improve psychological health in non-clinical adults (McClintock et al., 2019). A variety of retreat styles and training intensities have been developed, with durations ranging from less than 1 week (Khoury et al., 2017), 1 week (Cohen et al., 2017), 1 month (Zanesco et al., 2013), to 3 months (Cahn et al., 2017). Findings reported significant improvements in measures of self-reported anxiety, mindfulness, and attentional control in naive participants (Cohen et al., 2017; Kozasa et al., 2015), as well as in expert meditators (Chambers et al., 2009; Lutz et al., 2008), where some but not all observed effects were reported 1 month after the retreat (Zanesco et al., 2016). Physiological changes have also been reported, such as reductions in stress and anxiety with moderate to large effect sizes (Kozasa et al., 2015; Montero-Marin et al., 2016) and reductions in biomarkers of stress and inflammation following just a 3-day mindfulness retreat (Gardi et al., 2022).

Some evidence suggests that psychological health and attentional variables can be improved following a mindfulness retreat (Blanco et al., 2020). These findings are consistent with most of the currently available theoretical models highlighting the significant role of attention regulation in facilitating emotional and cognitive flexibility (Malinowski, 2013). This flexibility, in turn, promotes the enhancement of emotion regulation processes (Guendelman et al., 2017) and the capability to sustain non-judgmental awareness of one’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

Nonetheless, important shortcomings are highlighted in the literature. McClintock et al. (2019) reported low quality in the retreat studies assessed in their meta-analysis, highlighting methodological limitations such as lack of active control groups, and lack of random assignment and follow-up assessment, which are common drawbacks in the field (Zangri et al., 2022) that must be addressed to further our understanding of the mechanisms by which meditation produces its beneficial effects in retreat formats (McClintock et al., 2019). Furthermore, while there is evidence of the effects of mindfulness retreats in improving psychological outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and stress in healthy adult populations (Khoury et al., 2015; McClintock et al., 2019), other popular meditation practices such as compassion-based interventions are less studied in intensive retreat formats (Skawara et al., 2017).

Considerable research has been conducted on structured mindfulness-based interventions (Wielgosz et al., 2019), showing improvements in psychological outcomes, such as mindfulness, compassion, and acceptance, as well as reducing psychological symptoms and improving quality of life and sleep (Creswell, 2017; Khoury et al., 2015; Rash et al., 2019) in non-clinical adults (Galante et al., 2021). A popular concept to describe mindfulness meditation is the directed and non-judgmental attention to the present moment (Kabat-Zinn, 2005), where individuals train the ability to engage and modulate their attention to the present experience, with an accepting and non-judgmental attitude (Bishop, 2004).

On the other hand, structured compassion-based interventions (Goldin & Jazaieri, 2017) aim to cultivate compassion and kindness towards oneself and others as a means of promoting mental health and well-being. Compassion refers to the genuine acknowledgment of the emotional, physical, or psychological suffering experienced by oneself or others, coupled with a sincere desire and effort to prevent and alleviate it (Gilbert & Choden, 2013). Meta-analytic reviews have shown that these interventions significantly increase compassion, mindfulness, and well-being, as well as decrease symptoms of anxiety, depression, and psychological distress, in clinical (Millard et al., 2023) and non-clinical samples (Kirby et al., 2017).

Research on both mindfulness and compassion-based interventions has shown promising results not only for reducing distress but also for enhancing mental health and well-being in healthy adults (Galante et al., 2021; McClintock et al., 2019; Spijkerman et al., 2016; van Agteren et al., 2021). Among these, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1982) and Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT; Goldin & Jazaieri, 2017) are two of the most widely studied evidence-based interventions in the field. These programs share structure, being typically group-based and running for 8-week/16-hr formats, following a well-defined curriculum of formal and informal practice, which has allowed their replicability in several contexts (e.g., workplace, clinical settings, and education; Crane et al., 2017). Recent head-to-head comparisons of MBSR and CCT indicate that mindfulness and compassion practices share certain favorable changes in outcomes and mechanisms, while also highlighting distinctions specific to each practice, as evidenced by empirical studies (Brito-Pons et al., 2018; Roca & Vazquez, 2020; Roca et al., 2021, 2023; Singer & Engert, 2019). While MBSR favors changes in present-moment awareness mechanisms, CCT relies on changes in common humanity, compassion, and empathy as socio-emotional mechanisms (Roca et al., 2021, 2023). In the contemplative tradition, the practice of mindfulness is a fundamental requirement for other meditation practices (Dahl & Davidson, 2019); in fact, mindfulness is formally practiced at the beginning of CCT. At the same time, self-compassion and kindness are implicitly taught in MBSR (Neff & Dahm, 2015). However, we do not yet know precisely how mindfulness may facilitate other meditation practices, such as compassion, or whether compassion is crucial in mindfulness programs.

In the structure of MBSR and CCT programs, it is commonly accepted that practices should be sequenced in a manner that initiates with mindfulness practices, subsequently followed by more affectively active practices such as self-compassion. This sequential approach suggests a gradual progression, where mindfulness is initially established as a foundation, thereafter transitioning into emotionally engaging practices. For instance, in MBSR, affective practices are typically incorporated during the intensive practice day, encompassing compassion/self-compassion exercises. In contrast, CCT begins with initial sessions focused on mindfulness practices, followed by a progressive journey into compassion practices. However, it is noteworthy that despite this intentional structuring, empirical evidence specifically supporting the efficacy of this sequence is sparse. The absence of empirical evidence underpinning this structured practice raises questions about the optimization of intervention protocols to maximize psychological benefits. This observation underscores the need for further investigation into how the sequence of mindfulness and compassion practices influences the outcomes of interventions, which could significantly contribute to our understanding of how different configurations of practices affect emotional and cognitive processes in participants.

Furthermore, the potential sequential and cumulative effects of these practices have yet to be examined, as well as the feasibility of conducting them in a brief and intensive retreat format to increase their accessibility. In fact, although interventions in the field have been widely researched and shown to be effective, there is a dearth of studies examining the differential impact of these programs on psychological health in the context of intensive multi-day interventions such as retreats.

The optimization and streamlining of mental health interventions are significant challenges for disseminating and making treatments accessible. The growing demand for more accessible and compact interventions has given rise to the study of brief and intensive interventions to improve psychological outcomes, where authors have found efficacy in formats of two sessions or even one individual session, known as single-session interventions (Schumer et al., 2018). In the literature, we can find support for interventions based on cognitive behavioral therapy or acceptance and commitment therapy with a brief and intensive format (Hazlett‐Stevens & Craske, 2002; Ruiz et al., 2020).

Meditation retreats could provide the opportunity to implement brief and intensive interventions to improve psychological outcomes and well-being in non-clinical populations (McClintock et al., 2019). However, according to the available literature, the type of meditation generally examined in intensive interventions does not follow a structured format, which limits the replicability of the results. In the case of MBSR and CCT programs, which generally have an 8-week format, there are already variations in the protocols to compact and improve the accessibility of these interventions with short and intensive formats ranging from single-session inductions, often in laboratory studies (vanOyen Witvliet et al., 2010), to 2-week (e.g., Bergen-Cico et al., 2013; Kirby et al., 2024; Smeets et al., 2014) and 4-week programs (Spijkerman et al., 2016) and with few recent adaptations in intensive retreat formats (Djernis et al., 2021).

Meta-analytic evidence has shown that brief mindfulness training (i.e., from single sessions up to 2 weeks of training) has a small effect on reducing negative affectivity in clinical and non-clinical populations (Schumer et al., 2018). In the case of compassion-based interventions, such as Compassion Focused Therapy, a systematic review found that even a brief intervention can reduce levels of psychopathology in clinical samples (Craig et al., 2020). Their evidence was also supported by a recent meta-analysis that found compassion-based interventions to be effective at increasing compassion and reducing clinical symptoms such as depression (Millard et al., 2023). There is promising indication from the extant literature that the observed changes might be maintained following retreat interventions (Cohen et al., 2017; MacLean et al., 2010), where changes on variables like self-compassion, fear of compassion, or distress have been found 6 months after a brief compassion intervention in healthy individuals (McEwan & Gilbert, 2016). Nonetheless, authors highlight the need to improve the methodological quality of the studies and the need for further research to explore the long-term effects of these interventions (Millard et al., 2023). Therefore, it is important to explore the benefits of structured mindfulness and compassion-based interventions in a brief, intensive retreat format for improving psychological outcomes in non-clinical populations, preserving the integrity of the interventions to the highest degree possible (Ainsworth et al., 2023).

The present study explored a novel approach to the study of MBSR and CCT interventions by using compact versions of these programs in an intensive retreat format while preserving the maximum integrity of the original programs (i.e., format and contents of each session and level of guidance by the instructors). Specifically, we analyzed both the differential and cumulative effects of these two interventions and whether the sequential order of program administration might significantly influence the results in a sample of healthy volunteers taking part in a 7-day retreat, where participants received both interventions sequentially, in a crossover design. We hypothesized an overall reduction of distress and an increase in well-being after both programs with no major difference in primary outcomes. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to employ a sequential crossover design with two intensive meditation programs. Thus, we did not formulate precise hypotheses regarding the effects of the order of the interventions (MBSR or CCT first) and their combined effects on the selected psychological outcomes. Finally, based on previous evidence, we predicted that the observed changes associated with the intervention would remain at the 3-month follow-up.

Method

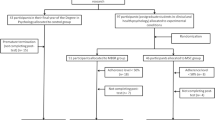

The present study is a crossover randomized controlled trial in compliance with SPIRIT reporting guidelines. Details of the study protocol design have been fully described elsewhere (Diez et al., 2023). Participants engaged in a 7-day retreat involving training in two meditation-based programs: MBSR and CCT. Randomization was performed by the principal investigator using the Research Randomizer Program and the restriction of maintaining the same percentage of female and male participants in both groups. Participants underwent their first meditation training in the first 3 days of the retreat (i.e., starting with MBSR or CCT), and then switched to the second meditation training in the last 3 days of the retreat (i.e., finishing with the other type of training). Psychological measures were collected online from both groups on the mornings of Day 1 (before beginning the retreat), Day 4 (after the first meditation program and before the beginning of the second program), and Day 7 (at the end of the retreat), and at the 3-month follow-up assessment (Fig. 1). Participants were blinded to group allocation starting with MBSR or CCT, remained uninformed about the study hypotheses, and gave their written informed consent before their inclusion in the study.

Participants

Figure 2 illustrates the participation flow diagram. Inclusion criteria were being a healthy adult between 25 and 65 years old (i.e., participants underwent a screening questionnaire and telephone interview) and it did not matter whether they had previous meditation experience. Exclusion criteria included current or past serious mental disorders (e.g., major depression, bipolar disorder), medical conditions affecting the immune system (e.g., autoimmune diseases, HIV), pregnancy, and current substance abuse. Individuals with current habits (i.e., smoking, alcoholism, substance abuse) or taking specific medications (e.g., corticoids) that might affect the immune system were also excluded. Also, individuals planning to travel from a different time zone or long-travel times were excluded. These exclusion criteria were due to the possible effect on the physiological measures collected for a secondary study purpose on biological measures.

A total of 49 participants from the general population were randomly assigned to the group starting with MBSR (n = 25) or the group starting with CCT (n = 24). Participants’ mean age was 50.51 (SD = 9.37), 77.6% were women, 87.2% had higher education, 40.8% were married, and 61.2% were employed. Most of the participants (83.7%) had experience with meditation, 63.4% were currently practicing meditation, and 65.9% had participated in a meditation retreat. The mean duration of previous meditation practice was 82.92 months (SD = 121.52), which was computed based on the difference between the total months the person meditated throughout their life and the total number of months the person interrupted their meditation practice. The groups starting with MBSR or CCT did not differ at baseline in age (t(47) = 0.88, p = 0.39), gender (χ2(1) = 2.67, p = 0.11), prior meditation experience (χ2(1) = 0.22, p = 0.64), or the mean number of months of previous meditation practice (t(47) = 0.64, p = 0.53).

We used the G*Power software to estimate sample size a priori, using order of intervention as a between-subject factor (MBSR first vs CCT first) and time as a within-subjects factor (4 times of assessment), we would need at least 21 participants per group to obtain a power of 95% to detect a mean effect size of 0.37 (based on well-being outcomes in mindfulness retreats; McClintock et al., 2019). We estimated a sample loss of less than 20%, so we increased the sample to 26 participants for each condition (52 in total).

Procedure

Participants were recruited through the website of a research center affiliated with our university (Nirakara Lab-UCM), devoted to the research and dissemination of mindfulness and compassion-based programs. Individuals interested in participating in the retreat were interviewed to screen their suitability for the study (i.e., inclusion and exclusion criteria). The screening process involved potential participants expressing interest and commitment through an online form, providing information on demographics, physical and psychological health history, and meditation experience. Participants were informed about the retreat details, including date, location, price, and program characteristics. A waiting list was created for those unable to sign up in time, expressing a desire to be considered if a place became available.

The study took place during the last week of August 2022. Upon arrival at the retreat center, participants received detailed information about the retreat rules, covering aspects such as food and accommodation, guidelines for maintaining silence, and the restricted use of electronic devices. Each participant was provided with a personalized schedule outlining specific timings for retreat activities and individual assessment sessions. After completing the first intervention arm of the study (i.e., MBSR or CCT first), participants underwent a half-day break before being assigned to the second intervention arm.

Participants were responsible for covering the retreat expenses (i.e., meals and accommodation), and did not receive financial compensation for their involvement in the study. Individuals provided written informed consent, outlining all study conditions, and they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without providing an explanation or facing any penalties. The research team was committed to supporting participants and helped as needed during the retreat.

Each meditation program followed the contents of standard MBSR and CCT programs in an intensive format (i.e., 3 days each). The MBSR program was administered by two instructors certified by the Mindfulness Center at Brown University. On the other hand, the CCT program was administered by two instructors certified by the Compassion Institute at Stanford University. Further details about the program contents are outlined in the supplementary material (Supplementary Table 1. Description of the main practices of the retreat).

Throughout the retreat, participants were instructed to maintain silence, refraining from communicating with each other and abstaining from the use of electronic devices. On each retreat day, participants engaged in various group activities, including 4.25 hr of sitting meditation, 2 hr of walking meditation, 2 hr of interactions with instructors for explanations and discussions related to the practices, and 1 hr dedicated to mindful body movements such as yoga or qigong. In total, participants engaged in 9 hr of practice each day.

Measures

The online assessment was administered via Qualtrics software, including a set of scales evaluating different domains related to meditation practice, and was completed in dedicated rooms with computers. Most of these measures were developed in studies with the general population showing good or excellent psychometric properties and have also been used in previous mindfulness intervention studies in healthy individuals. Table 1 summarizes the psychological measures used in the study.

Data Analyses

Independent samples t-tests for continuous data and Chi-square test for categorical data were used to analyze baseline differences between groups starting with MBSR or CCT. Only 2.5% of the overall data were missing completely at random (Little MCAR test: χ2 (54) = 44.97, p = 0.80). Intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were performed following Newman’s guidelines (Newman, 2014), using Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method.

Mixed-effects models were conducted to analyze the meditation retreat effects, using the lmer function from the lme4 R-package (Bates et al., 2015). Mixed models were performed using Restricted Maximum Likelihood estimation (REML; Graham, 2009; Little & Rubin, 2002), which offers a less-biased estimate of variance components, especially suitable for smaller sample sizes and datasets with missing values (Graham, 2009; Molenberghs & Kenward, 2007; Schafer & Yucel, 2002). Order (i.e., group starting with MBSR or CCT) and Time (i.e., baseline [Day 1], inter-retreat [Day 4], post-retreat [Day 7], and 3-month follow-up) were modeled as fixed effects in the model, whereas variance across participants and previous meditation experience (i.e., total months the person has meditated throughout their life) were modeled as a random effect to account for individual differences in the dependent variables. We used the group starting with CCT and the baseline assessment as the arbitrary reference categories to compare the results in the Order and Time factors respectively. Fixed-effect parameters (b) were interpreted as the regression weights in the linear regression models, in which parameter estimates represent the changes in the mean of the dependent variable between the reference category and the contrast (Cohen et al., 2013). Model-derived fixed-effect parameter regression weights (b) were used as the effect size of each model (Rodríguez-Gómez et al., 2020). Furthermore, when significant differences were found, Tukey-corrected post hoc comparisons were computed to determine which specific order and times differed from each other. R version 4.3.1 was used for the analyses (R Core Team, 2014).

Results

Table 2 presents fixed-effect parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals for each dependent variable. Furthermore, Fig. 3 depicts the means of the Order × Time interactions on the dependent variables.

Line graph with the mean of Order (red line and squares = starting with CCT; blue line and triangles = starting with MBSR) × Time (1 = baseline – 1st day; 2 = inter-retreat – 4th day; 3 = post-retreat – 7th day; 4 = 3-month follow-up) interactions. The error bars represent the standard error for each 95% confidence interval

Emotional Distress and Regulation

We found a significant main effect of Time for stress, which revealed lower levels of symptoms of stress in both groups post-retreat (p = 0.002; b = 1.85). No significant differences between groups over time were found in the DASS-21 subscales of stress, anxiety, and depression symptoms (i.e., the Order × Time interactions were not significant). Participants in both groups had low levels of psychological distress at baseline, and those levels remained stable throughout the meditation retreat. Regarding changes in emotion regulation (S-DERS), there was also a significant Time main effect, showing a reduction in the difficulties in emotion regulation in both groups at the inter-retreat (p < 0.001; b = 0.33) and the post-retreat (p < 0.001; b = 0.49) relative to the baseline measurement. A significant Order × Time interaction revealed a significant decrease in the difficulties in emotion regulation at the 3-month follow-up in the group starting with MBSR (p < 0.001; b = 0.39), whereas no changes were found in the group starting with CCT (p = 0.93; b = 0.12).

Compassion Measures

A significant main effect of Time showed significant self-compassion improvements in both groups at the inter-retreat (p < 0.001; b = − 0.46) and the post-retreat (p < 0.001; b = − 0.78) compared to baseline measurements. Furthermore, a significant Order × Time interaction revealed that improvements in self-compassion (S-SCS) were maintained at follow-up in the group starting with MBSR followed by CCT (p = 0.002; b = − 0.52), whereas the effect vanished in the group starting with CCT followed by MBSR (p = 0.99; b = − 0.09). A significant main effect of Time showed significant reductions of the fear of compassion (FOC) in both groups at post-retreat (p < 0.001; b = 4.64) and follow-up (p < 0.001; b = 3.97) relative to baseline measurements. No significant differences between groups over time were found in measure of fear of compassion (i.e., Order × Time interactions were not significant).

Mindfulness Measures

The results on mindfulness of mental events (SMS-Mind) and mindfulness of bodily sensations (SMS-Body) revealed a significant main effect for Time. Compared to the baseline assessments, both groups significantly improved their mindfulness of mental events at inter-retreat (p < 0.001; b =—0.92) and post-retreat (p < 0.001; b = − 1.06), as well as their mindfulness of bodily sensations at inter-retreat (p < 0.001; b = − 1.01) and post-retreat (p < 0.001; b = − 1.13), whereas no changes were found at follow-up. This main effect was qualified by an Order × Time3 interaction and an Order × Time4 interaction. Regarding the Order × Time3 interaction, post hoc analyses showed a significantly larger increase in mindfulness of mental events in the group starting with MBSR (p < 0.001; b = − 1.28) than in the group starting with CCT (p < 0.001; b = − 0.84). Regarding the Order × Time4 interaction, the improvements in mindfulness of mental events were maintained at follow-up in the group starting with MBSR (p = 0.01; b = − 0.57), whereas the effect vanished in the group starting with CCT (p = 0.99; b = − 0.10). In the case of mindfulness of bodily sensations (SMS-Body), a significant difference between groups was found at inter-retreat (i.e., Order × Time2 interaction). Post hoc comparisons showed a significant increase in mindfulness of bodily sensations at inter-retreat in both groups, although the change was significantly larger in the group starting with MBSR (p < 0.001; b = − 1.29) than the group starting with CCT (p < 0.001; b = − 0.73).

Affective Experience

There was a significant Time main effect that affected all types of emotions except for the low-arousal negative affect category. Compared to the baseline assessment, both groups significantly improved at inter-retreat on their high-arousal positive affect (p < 0.001; b = − 1.22) and low-arousal positive affect (p < 0.001; b = − 1.85) and showed significant reductions of high-arousal negative affect (p < 0.001; b = 1.42). Furthermore, there was a significant improvement in low-arousal positive affect (p < 0.001; b = − 1.39) and a significant reduction in high-arousal negative affect (p < 0.001; b = 1.82) at post-retreat. No significant changes in affective experiences were found at follow-up. A significant Order × Time interaction revealed a reduction of the high-arousal negative affect at post-retreat in the group starting with MBSR (p < 0.001; b = 2.56), whereas no changes were found in the group starting with CCT (p = 0.12; b = 1.08).

Program Satisfaction

The average satisfaction after the meditation retreat was high, as shown by an average of 29 points out of 32 (SD = 3.46) in the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire and 71.4% of participants rated the quality of the retreat as “excellent”; 67.3% got the kind of retreat they wanted; 46.9% felt that almost all their needs had been met with the retreat; 73.5% definitely would recommend the retreat to a friend; 75.5% was very satisfied with the help received in the retreat; 75.5% felt that the retreat helped to deal more effectively with their problems; and 69.4% would definitely repeat the retreat in the future.

Side Effects

Regarding side effects of the retreat, assessed immediately after its conclusion (Time 3), participants reported having “frequently experienced” a variety of feelings and experiences in several domains: emotional sensitivity (44.9%), sleeping difficulties (40.9%), headaches or migraines (30.5%), sensitive hearing (30.5%), isolation (10.2%), traumatic re-experiencing (8.2%), anxiety (6.1%), difficulties to think clearly (4%), difficulties in enjoying activities (4%), feelings of being disconnected from everything (2%), and “Other side effects” (12.2%).

Discussion

The present study investigated the efficacy of two structured programs, MBSR and CCT, delivered in a brief and intensive retreat format with a novel crossover design in a population of healthy individuals.

The analyses comparing the outcomes at the end of the 3-day intervention programs relative to the baseline assessment revealed a significant reduction in emotion regulation difficulties (assessed with the S-DERS scale) and a significant increase in self-compassion (S-SCS scale). These changes, all in the expected direction of psychological improvement, were similar for MBSR and CCT.

Regarding mindfulness outcomes (assessed with the SMS scale), compared to the baseline assessments, both groups significantly improved their mindfulness of mental events (emotions, thoughts, and other mental events) and mindfulness of bodily sensations (physical sensations). The improvement in mindfulness of bodily sensations was significantly larger in the MBSR group compared to the CCT group. In terms of changes in affect (measured with the HAAS scale), both groups showed significant increases in positive affect (high arousal: interested, active, strong; low arousal: calm, placid, content) and reductions in high arousal negative affect (anxious, irritable, guilty), highlighting the importance of investigating these distinctions in affect (Gilbert et al., 2008).

These findings align with previous meta-analytic evidence on the effectiveness of meditation retreats, which examined studies ranging from 3 to 90 days (Khoury et al., 2017). The authors did not find differences in meditation style, and they also reported that the effect sizes of the observed changes were not moderated by the retreat duration, although most studies included in the meta-analysis employed a 10-day format. These results further support previous research showing favorable changes after a brief MBSR intervention (Bergen-Cico et al., 2013) and brief compassion training, although the latter has been mainly researched in clinical populations (Feliu-Soler et al., 2017; Kelly & Carter, 2015). This promising evidence for the beneficial effects of brief and intensive meditation retreat formats on psychological outcomes suggests comparable results to those of traditional 8-week MBSR and CCT programs (Brito-Pons et al., 2018; Roca et al., 2021), thus increasing the applicability of these interventions.

The analyses at the end of the retreat allowed us to examine the effects of the order of administration of the programs as well as their cumulative effects. We found a significant reduction in the distress subscale of the DASS-21, which measures non-specific arousal-related problems (e.g., being easily upset, over-reactive, or having difficulties relaxing), regardless of group allocation, following the 7-day retreat. The subscales of depression and anxiety of the DASS-21 remained stable, and at very low levels of symptom severity, throughout the retreat. Overall, these results are relevant as they suggest that specific requirements of the retreat (e.g., prolonged silence, limited contact with the outside) did not negatively impact participants’ levels of distress.

Regarding self-compassion and mindfulness measures, a significant reduction in fear of compassion, accompanied by significant improvements in mindfulness of mental events and mindfulness of bodily sensations, was observed in both groups at the end of the retreat. However, the order of the treatments was relevant. In the case of mindfulness of bodily sensation, the group starting with MBSR showed an advantage compared to the CCT-first group after only 3 days of intervention. In the case of mindfulness of mental events, although both groups show improvements after 3 days, the MBSR group showed an advantage after 7 days of intervention (post-retreat). Thus, it appears that for the group starting with MBSR training, mindfulness of bodily changes might precede cognitive ones.

We also found improvements in the affective experience at the end of the programs. At the end of the interventions, both groups exhibited higher scores in adjectives measuring low-arousal positive affect states (i.e., calm, placid, content) and a reduction of high-arousal negative affect (i.e. anxious, irritable, and guilty). The order of the interventions on the observed changes in affect was significant. As it also happened with changes in mindfulness of bodily sensations, compared to the baseline assessment, the group starting with MBSR training showed a reduction in high-arousal negative affect at the end of the retreat but the group starting with CCT, although also showing reduced high-arousal negative affect at the end of its 3-day program, did not show significant differences at the end of the retreat, compared to baseline levels.

Overall, these results confirm that an intensive 7-day meditation retreat reduces distress and increases well-being in healthy volunteer individuals. The findings are in line with current literature showing the beneficial effects of brief and intensive meditation retreats on psychological outcomes in non-clinical adults (Khoury et al., 2015; McClintock et al., 2019).

In this context, the present study provides novel evidence on the differential and order effects of these interventions, where it appears that although the combined effect of MBSR and CCT intensive training favors positive changes in a range of psychological domains, the order of these interventions matters. Order-related differences were found for measure such as mindfulness and high-arousal negative affect, where the group starting with MBSR training showed better outcomes.

The 3-month follow-up analyses revealed no significant changes in symptoms of distress for any intervention group, compared to baseline assessments. It should be noted that participants underwent a screening for mental health and physical health conditions before enrolling in the study. Therefore, the possibility of finding significant changes in this domain was reduced. However, there were changes in other psychological variables and, in this case, some interesting order-related effects were found. Again, whenever the order played a significant role in the outcomes observed, the group starting with MBSR training showed better results than the other group starting with CCT. This was evident in a decrease in emotion regulation difficulties, which was not observed in the group starting with CCT. This result suggests benefits in emotion regulation beyond the retreat intervention, consistent with previous research (Zanesco et al., 2013, 2016). In the case of self-compassion, the group starting with MBSR maintained the improvements in self-compassion 3 months after the retreat, whereas the effect vanished in the group starting with CCT. The observed results might be due to the combination of starting with MBSR training and ending with CCT, the latter being centered around attention to, and regulation of, emotional experiences. Moreover, participants of both groups showed significant decreases in their fear of compassion at follow-up, suggesting that for this measure, the cumulative effect of the interventions was beneficial, and the order of the interventions did not matter.

Significant order-related results were again observed for mindfulness outcomes at follow-up, where the group receiving MBSR training first maintained the increased mindfulness of mental events, whereas in the group starting with CCT the benefits observed after the 3-day training and at the end of the retreat vanished after 3 months. Similarly, the benefits in affective states are washed out at follow-up.

These results are promising in the context of disentangling the mechanisms of action that might be mediating the observed changes. While previous research found comparable psychological changes following standard MBSR and CCT interventions (Roca & Vazquez, 2020; Roca et al., 2023), different mechanisms underlying mindfulness and compassion interventions have also been identified (Brito-Pons et al., 2018; Roca et al., 2021; Singer & Engert, 2019). The results of the present study suggest that although both study arms showed changes in the expected directions, when analyzing the combined effects of the interventions, the order might impact the significance and magnitude of psychological outcomes, where receiving intensive MBSR training followed by CCT puts the individual at an advantage to retain certain benefits such as increased mindfulness of mental events and retaining long-term benefits in compassion measures. Due to the novelty of the study design, this should be explored by further research to better understand specific mechanisms of change for the observed psychological benefits.

Overall, both interventions produced changes in key psychological domains in the expected direction, supporting the beneficial effects of mindfulness and compassion-based interventions reported in the literature (Creswell, 2017; Khoury et al., 2017; McClintock et al., 2019), but in this case in a brief and intensive format. In terms of cumulative effects, both groups showed positive changes in measures of psychological well-being, regardless of the intervention order, such as emotion regulation, affective experience, mindfulness, and self-compassion following the retreat. However, some of these benefits were lost at the 3-month follow-up, especially in the case of participants who started with CCT followed by MBSR. The results are contrary to previous research that found that all psychological gains on measures of mindfulness, anxiety, depression, and dysfunctional attitudes were maintained 1 month after participants took part in a Vipassana retreat (Cohen et al., 2017). However, the present study includes a novel crossover design, two active intervention groups based on structured programs, and a 3-month follow-up, which might explain the differences observed.

Nonetheless, the results observed are promising if we consider the sample population in the present study. Whereas in other similar types of retreats, no exclusion criteria were applied (e.g., Cohen et al., 2017), in our case the selection criteria were rather strict to rule out mental or physical conditions that might affect the biological measures collected in this retreat for research purposes that go beyond the present study (Diez et al., 2023). The participants exhibited good physical health and self-reported mental health, due to which any observed changes in psychological domains do provide a notable result of the intervention. These findings support previous literature showing how mindfulness interventions favor mental health improvements in healthy participants (Khoury et al., 2017). It should also be noted that participants were not all meditation novices, which supports the restorative effects of retreats even for experienced practitioners (Kozasa et al., 2015; Montero-Marin et al., 2016). Nonetheless, to account for individual differences, we included variance across participants and their previous meditation experience as random effects in the analyses performed.

A strength of the study lies in the use of a randomized crossover design, which to the best of our knowledge has not been applied in a retreat intervention. The choice of design allowed for the testing of the separated effects of compacted, intensive formats of MBSR and CCT programs, and to investigate possible order or cumulative effects of these interventions in a highly controlled retreat environment. Furthermore, both interventions were delivered by certified and experienced instructors, ensuring the fidelity of the programs’ curriculum in their adaptation and delivery. Two instructors delivered each study arm (MBSR or CCT) to ensure compliance with the study protocol, which is a limitation highlighted by previous meta-analytic evidence (McClintock et al., 2019). A further strength can be found in the fact that these structured interventions preserved the core active ingredients of the original programs as much as possible, which offers the possibility to compare our results to the standard 8-week programs, which allows the possibility to advance scientific knowledge in the field (Crane et al., 2017). Also, this study has the added value of having selected validated outcome measures that have highly been used in the literature in this field (Gherardi-Donato et al., 2020; Strauss et al., 2016).

A common limitation in mindfulness literature is the lack of long-term assessments (Cohen et al., 2017; McClintock et al., 2019), for which a relevant strength of the present study is that we included a 3-month follow-up measure. It should also be noted that retreat studies report fewer dropouts compared to meta-analytic data on standard mindfulness programs such as MBSR (7.7% attrition compared to 17%) (Khoury et al., 2017). The authors argued that this could be due to most studies employing self-selected participants who could show higher motivation to engage in the training received during the retreat. In the present study, great efforts were dedicated to selecting outcome measures that would not tax participants’ engagement during the retreat and that would allow fewer dropouts at follow-up. As a result, there were no participant dropouts during the retreat and the completion of assessments at the 3 month was very high, which compares favorably to similar studies reporting a completion rate of just 48% in a 4-week follow-up (Cohen et al., 2017). The results from the present follow-up are insightful, showing how some important changes in psychological outcomes such as mindfulness of mental events and emotion regulation are maintained 3 months after the retreat, whereas others such as affective experience appear to wash out. These results could be addressed by future studies to determine which active ingredients or optimal durations of the interventions are needed for people to retain these benefits.

Limitations and Future Directions

Some limitations need consideration in the interpretation of the present study findings. Notably, a subset of participants had prior meditation experience from various traditions, although these statistical analyses rigorously controlled for the degree of practice. Despite this statistical control, future investigations should explore the potential influence of different meditation types at baseline, as the diversity of participants’ prior experiences might introduce nuances. Moreover, it should be noted that the sample of participants voluntarily signed up for the meditation retreat, which could indicate some extent of self-selection bias, similar to challenges faced by most meditation studies, where achieving blinding and random allocation proves difficult, as highlighted in the literature (Cohen et al., 2017; Vago et al., 2019; Van Dam et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the comparison of two standardized active interventions helps to mitigate potential confounding effects related to motivation, demand characteristics, or differences between experts and novices, as suggested by prior research (Malinowski, 2013; Wallace & Shapiro, 2006).

Due to logistic constraints and the challenge of extending participants’ stay, there was not an extended washout period between meditation programs. This decision was supported by the consideration that extended intervals could introduce difficult-to-control confounding variables, such as varying life events experienced by individuals, making program comparability more challenging. This approach aligns with the standard practice in psychological studies conducting a crossover design (e.g., Geschwind et al., 2019).

Factors associated with the courses, such as instructor’s characteristics, may have introduced additional sources of variability. To mitigate this risk, the same MBSR or CCT instructors provided the training to the assigned group, and all instructors were certified and experienced. However, there may have been individual differences that could have influenced the training, and although the instructors carefully adhered to the program’s curriculum, homework exercises characteristic of these programs could not be included due to the design of the intensive interventions.

Our study design, utilizing a crossover approach, offers valuable insights into crucial research questions, particularly concerning the potential additive effects of the two modalities under investigation. We believe that the short (i.e., 3-day interventions) and intense (i.e., administering almost all program components) format of our interventions also opens up new opportunities to deliver MBIs in alternative modes. However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations that may impact the generalizability of our findings to different settings. The compact and intensive training provided during the retreats condensed into a short time frame may not fully represent the more extended, ongoing practices observed in other real-world scenarios. Additionally, the exposure to various contingencies associated with the retreat environment, such as periods of silence and rest days, introduces factors that could contribute to the observed changes (Blasche et al., 2021; Norman & Pokorny, 2017). These unique aspects of the retreat context may add complexity to the interpretation of results and warrant careful consideration in extrapolating findings to diverse settings or populations. Although our study does not allow us to dismantle the impact of all the format-related components included in the program (e.g., retreat vs non-retreat, silence vs. no silence, intensive vs. no intensive), we firmly believe that it opens some new interesting avenues in the research on MBIs. As Ainsworth et al. (2023) have pointed out, there is a need to improve access to meditation-based interventions while preserving the fidelity of the programs. This tension can only be solved with empirical research showing the efficacy of different variations in the existing programs.

Lastly, some adverse effects that have been previously reported in mindfulness training (Britton et al., 2021; Farias et al., 2020) were identified by a small proportion of participants, the most frequent ones being emotional sensitivity and headaches. It could be possible that the sensitive emotional content handled, mostly in the CCT program, and the long hours spent in training may have given rise to some minor emotional and physical distress. This could also be due to specific characteristics of the retreat setting (e.g., sleeping in a different environment, dietary issues, or maintaining silence). Thus, we highlight the importance of including measures of side effects from the mindfulness literature and that the training be provided by certified instructors who are aware of and able to address these potential difficulties. Nonetheless, almost all participants showed high satisfaction with the retreat and reported that it helped them deal more effectively with their problems.

To conclude, the present study shows the beneficial effects of a 7-day meditation retreat, employing two brief and intensive MBSR and CCT adaptations. The study addresses some pending questions in the literature by comparing two active interventions with a crossover design. The study shows insightful evidence on the differential and cumulative effects of these interventions in psychological measures. Most importantly, it suggests that the beneficial psychological effects of the meditation practice are enhanced, in general, when the participant starts with MBSR and continues with CCT. Finally, we provide indications of long-term efficacy of meditation retreats with a 3-month follow-up analysis and highlight the practical applications of brief and intensive interventions for healthy populations.

Data Availability

References

Ainsworth, B., Atkinson, M. J., AlBedah, E., Duncan, S., Groot, J., Jacobsen, P., James, A., Jenkins, T. A., Kylisova, K., Marks, E., Osborne, E. L., Remskar, M., & Underhill, R. (2023). Current tensions and challenges in mindfulness research and practice. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 53(4), 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09584-9

Attkisson, C. C., & Zwick, R. (1982). The client satisfaction questionnaire: Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning, 5(3), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-X

Bates, D., Kliegl, R., Vasishth, S., & Baayen, H. (2015). Parsimonious mixed models. arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1506.04967

Bergen-Cico, D., Possemato, K., & Cheon, S. (2013). Examining the efficacy of a brief Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Brief MBSR) program on psychological health. Journal of American College Health, 61(6), 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2013.813853

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Blanco, I., Roca, P., Duque, A., Pascual, T., & Vazquez, C. (2020). The effects of a 1-month meditation retreat on selective attention towards emotional faces: An eye-tracking study. Mindfulness, 11(1), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01247-y

Blasche, G., deBloom, J., Chang, A., & Pichlhoefer, O. (2021). Is a meditation retreat the better vacation? Effect of retreats and vacations on fatigue, emotional well-being, and acting with awareness. PLoS ONE, 16(2), e0246038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246038

Brito-Pons, G., Campos, D., & Cebolla, A. (2018). Implicit or explicit compassion? Effects of compassion cultivation training and comparison with Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction. Mindfulness, 9(5), 1494–1508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0898-z

Britton, W. B., Lindahl, J. R., Cooper, D. J., Canby, N. K., & Palitsky, R. (2021). Defining and measuring meditation related adverse effects in mindfulness-based programs. Clinical Psychological Science, 9(6), 1185–1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702621996340

Cahn, B. R., Goodman, M. S., Peterson, C. T., Maturi, R., & Mills, P. J. (2017). Yoga, meditation and mind-body health: Increased BDNF, cortisol awakening response, and altered inflammatory marker expression after a 3-month yoga and meditation retreat. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 315. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00315

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge.

Cohen, J. N., Jensen, D., Stange, J. P., Neuburger, M., & Heimberg, R. G. (2017). The immediate and long-term effects of an intensive meditation retreat. Mindfulness, 8(4), 1064–1077. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0682-5

Craig, C., Hiskey, S., & Spector, A. (2020). Compassion focused therapy: A systematic review of its effectiveness and acceptability in clinical populations. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 20(4), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2020.1746184

Crane, R. S., Brewer, J., Feldman, C., Kabat-Zinn, J., Santorelli, S., Williams, J. M., & Kuyken, W. (2017). What defines mindfulness-based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003317

Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 68, 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139

Dahl, C. J., & Davidson, R. J. (2019). Mindfulness and the contemplative life: Pathways to connection, insight, and purpose. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 60–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.11.007

Diez, G. G., Martin-Subero, I., Zangri, R. M., Kulis, M., Andreu, C., Blanco, I., Roca, P., Cuesta, P., García, C., Garzón, J., Herradón, C., Riutort, M., Baliyan, S., Venero, C., & Vázquez, C. (2023). Epigenetic, psychological, and EEG changes after a 1-week retreat based on mindfulness and compassion for stress reduction in healthy adults: Study protocol of a cross-over randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 18(11), e0283169. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283169

Djernis, D., O’Toole, M. S., Fjorback, L. O., Svenningsen, H., Mehlsen, M. Y., Stigsdotter, U. K., & Dahlgaard, J. (2021). A short mindfulness retreat for students to reduce stress and promote self-compassion: Pilot randomised controlled trial exploring both an indoor and a natural outdoor retreat setting. Healthcare, 9(7), 910. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9070910

Farias, M., Maraldi, E., Wallenkampf, K. C., & Lucchetti, G. (2020). Adverse events in meditation practices and meditation-based therapies: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(5), 374–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13225

Feliu-Soler, A., Pascual, J. C., Elices, M., Martín-Blanco, A., Carmona, C., Cebolla, A., Simón, V., & Soler, J. (2017). Fostering self-compassion and loving-kindness in patients with borderline personality disorder: A randomized pilot study. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24(1), 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2000

Galante, J., Friedrich, C., Dawson, A. F., Modrego-Alarcón, M., Gebbing, P., Delgado-Suárez, I., Gupta, R., Dean, L., Dalgleish, T., White, I. R., & Jones, P. B. (2021). Mindfulness-based programmes for mental health promotion in adults in nonclinical settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS Medicine, 18(1), e1003481. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003481

Gardi, C., Fazia, T., Stringa, B., & Giommi, F. (2022). A short mindfulness retreat can improve biological markers of stress and inflammation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 135, 105579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105579

Geschwind, N., Arntz, A., Bannink, F., & Peeters, F. (2019). Positive cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression: A randomized order within-subject comparison with traditional cognitive behavior therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 116, 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.03.005

Gherardi-Donato, E. C., Moraes, V. S., Esper, L. H., Zanetti, A. C. G., & Fernandes, M. N. (2020). Mindfulness measurement instruments: A systematic review. International Journal of Psychiatry Research, 3(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.33425/2641-4317.1066

Gilbert, P., & Choden. (2013). Mindful compassion. Constable & Robinson.

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Mitra, R., Franks, L., Richter, A., & Rockliff, H. (2008). Feeling safe and content: A specific affect regulation system? Relationship to depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760801999461

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Matos, M., & Rivis, A. (2011). Fears of compassion: Development of three self-report measures. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 84(3), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608310X526511

Goldin, P. R., & Jazaieri, H. (2017). The Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT) program. The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science, 1, 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190464684.013.18

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 549–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530

Guendelman, S., Medeiros, S., & Rampes, H. (2017). Mindfulness and emotion regulation: Insights from neurobiological, psychological, and clinical studies. In Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00220

Hazlett-Stevens, H., & Craske, M. G. (2002). Brief cognitive-behavioral therapy: Definition and scientific foundations. In F. W. Bond & W. Dryden (Eds.), Handbook of brief cognitive behaviour therapy (pp. 3–7). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470713020.ch1

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1982). An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: Theoretical considerations and preliminary results. General Hospital Psychiatry, 4(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2005). Coming to our senses: Healing ourselves and the world through mindfulness. Hachette UK.

Kelly, A. C., & Carter, J. C. (2015). Self-compassion training for binge eating disorder: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 88(3), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12044

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

Khoury, B., Knäuper, B., Schlosser, M., Carrière, K., & Chiesa, A. (2017). Effectiveness of traditional meditation retreats: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 92, 16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2016.11.006

King, B. G., Conklin, Q. A., Zanesco, A. P., & Saron, C. D. (2019). Residential meditation retreats: Their role in contemplative practice and significance for psychological research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.021

Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Steindl, S. R. (2017). A meta-analysis of compassion-based interventions: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 778–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.06.003

Kirby, J. N., Hoang, A., & Crimston, C. R. (2024). A brief compassion focused therapy intervention can increase moral expansiveness: A randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 15(2), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02300-7

Kozasa, E. H., Lacerda, S. S., Menezes, C., Wallace, B. A., Radvany, J., Mello, L. E. A. M., & Sato, J. R. (2015). Effects of a 9-day Shamatha Buddhist meditation retreat on attention, mindfulness and self-compassion in participants with a broad range of meditation experience. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1235–1241. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0385-8

Lavender, J. M., Tull, M. T., DiLillo, D., Messman-Moore, T., & Gratz, K. L. (2017). Development and validation of a state-based measure of emotion dysregulation. Assessment, 24(2), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115601218

Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2002). Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u

Lutz, A., Slagter, H. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Attention regulation and monitoring in meditation. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(4), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.005

MacLean, K. A., Ferrer, E., Aichele, S. R., Bridwell, D. A., Zanesco, A. P., Jacobs, T. L., King, B. G., Rosenberg, E. L., Sahdra, B. K., Shaver, P. R., Wallace, B. A., Mangun, G. R., & Saron, C. D. (2010). Intensive meditation training improves perceptual discrimination and sustained attention. Psychological Science, 21(6), 829–839. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610371339

Malinowski, P. (2013). Neural mechanisms of attentional control in mindfulness meditation. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00008

McClintock, A. S., Rodriguez, M. A., & Zerubavel, N. (2019). The effects of mindfulness retreats on the psychological health of non-clinical adults: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1443–1454. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12671-019-01123-9/TABLES/9

McEwan, K., & Gilbert, P. (2016). A pilot feasibility study exploring the practising of compassionate imagery exercises in a nonclinical population. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 89(2), 239–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12078

Millard, L. A., Wan, M. W., Smith, D. M., & Wittkowski, A. (2023). The effectiveness of compassion focused therapy with clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 326, 168–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.010

Molenberghs, G., & Kenward, M. (2007). Missing data in clinical studies. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470510445

Montero-Marin, J., Puebla-Guedea, M., Herrera-Mercadal, P., Cebolla, A., Soler, J., Demarzo, M., Vazquez, C., Rodríguez-Bornaetxea, F., & García-Campayo, J. (2016). Psychological effects of a 1-month meditation retreat on experienced meditators: The role of non-attachment. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1935. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01935

Neff, K. D., & Dahm, K. A. (2015). Self-compassion: What it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness. In B. D. Ostafin, M. D. Robinson, & B. P. Meier (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness and self-regulation (pp. 121–137). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2263-5_10

Neff, K. D., Tóth-Király, I., Knox, M. C., Kuchar, A., & Davidson, O. (2021). The development and validation of the State self-compassion scale (long- and short form). Mindfulness, 12(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01505-4

Newman, D. A. (2014). Missing data. Organizational Research Methods, 17(4), 372–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114548590

Norman, A., & Pokorny, J. J. (2017). Meditation retreats: Spiritual tourism well-being interventions. Tourism Management Perspectives, 24, 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.07.012

R Core Team (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

Rash, J. A., Kavanagh, V. A. J., & Garland, S. N. (2019). A meta-analysis of mindfulness-based therapies for insomnia and sleep disturbance. Sleep Medicine Clinics, 14(2), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2019.01.004

Roca, P., & Vazquez, C. (2020). Brief meditation trainings improve performance in the emotional attentional blink. Mindfulness, 11(7), 1613–1622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01374-x

Roca, P., Vazquez, C., Diez, G., Brito-Pons, G., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Not all types of meditation are the same: Mediators of change in mindfulness and compassion meditation interventions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 283, 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.070

Roca, P., Vazquez, C., Diez, G., & McNally, R. J. (2023). How do mindfulness and compassion programs improve mental health and well-being? The role of attentional processing of emotional information. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 81, 101895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2023.101895

Rodríguez-Gómez, P., Romero-Ferreiro, V., Pozo, M. A., Hinojosa, J. A., & Moreno, E. M. (2020). Facing stereotypes: ERP responses to male and female faces after gender-stereotyped statements. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 15(9), 928–940. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsaa117

Ruiz, F. J., Peña-Vargas, A., Ramírez, E. S., Suárez-Falcón, J. C., García-Martín, M. B., García-Beltrán, D. M., Henao, Á. M., Monroy-Cifuentes, A., & Sánchez, P. D. (2020). Efficacy of a two-session repetitive negative thinking-focused acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) protocol for depression and generalized anxiety disorder: A randomized waitlist control trial. Psychotherapy, 57(3), 444–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000273

Schafer, J. L., & Yucel, R. M. (2002). Computational strategies for multivariate linear mixed-effects models with missing values. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 11(2), 437–457. https://doi.org/10.1198/106186002760180608

Schumer, M. C., Lindsay, E. K., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Brief mindfulness training for negative affectivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(7), 569–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000324

Singer, T., & Engert, V. (2019). It matters what you practice: Differential training effects on subjective experience, behavior, brain and body in the ReSource Project. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.005

Skwara, A. C., King, B. G., & Saron, C. D. (2017). Studies of training compassion: What have we learned; what remains unknown? In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 219–236). Oxford University Press.

Smeets, E., Neff, K., Alberts, H., & Peters, M. (2014). Meeting suffering with kindness: Effects of a brief self-compassion intervention for female college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(9), 794–807. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22076

Spijkerman, M. P. J., Pots, W. T. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: A review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 102–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.009

Strauss, C., Lever Taylor, B., Gu, J., Kuyken, W., Baer, R., Jones, F., & Cavanagh, K. (2016). What is compassion and how can we measure it? A review of definitions and measures. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.004

Tanay, G., & Bernstein, A. (2013). State mindfulness scale (SMS): Development and initial validation. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1286–1299. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034044

Vago, D. R., Gupta, R. S., & Lazar, S. W. (2019). Measuring cognitive outcomes in mindfulness-based intervention research: A reflection on confounding factors and methodological limitations. Current Opinion in Psychology, 28, 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.015

van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Lo, L., Bartholomaeus, J., Kopsaftis, Z., Carey, M., & Kyrios, M. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(5), 631–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01093-w

Van Dam, N. T., van Vugt, M. K., Vago, D. R., Schmalzl, L., Saron, C. D., Olendzki, A., Meissner, T., Lazar, S. W., Kerr, C. E., Gorchov, J., Fox, K. C. R., Field, B. A., Britton, W. B., Brefczynski-Lewis, J. A., & Meyer, D. E. (2018). Mind the hype: A critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617709589

vanOyen Witvliet, C., Knoll, R. W., Hinman, N. G., & DeYoung, P. A. (2010). Compassion-focused reappraisal, benefit-focused reappraisal, and rumination after an interpersonal offense: Emotion-regulation implications for subjective emotion, linguistic responses, and physiology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(3), 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439761003790997

Wallace, B. A., & Shapiro, S. L. (2006). Mental balance and well-being: Building bridges between Buddhism and Western psychology. American Psychologist, 61(7), 690–701. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.690

Wielgosz, J., Goldberg, S. B., Kral, T. R. A., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2019). Mindfulness meditation and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 285–316. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093423

Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., Maclean, K. A., & Saron, C. D. (2013). Executive control and felt concentrative engagement following intensive meditation training. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 7, 566. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00566

Zanesco, A. P., King, B. G., MacLean, K. A., Jacobs, T. L., Aichele, S. R., Wallace, B. A., Smallwood, J., Schooler, J. W., & Saron, C. D. (2016). Meditation training influences mind wandering and mindless reading. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3(1), 12–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000082

Zangri, R. M., Andreu, C. I., Nieto, I., González-Garzón, A. M., & Vázquez, C. (2022). Efficacy of mindfulness to regulate induced emotions in the laboratory: A systematic review and meta-analysis of self-report and biobehavioral measures. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 143, 104957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104957

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Innovation (PID2019-108711 GB-I00) to Carmelo Vazquez and a Spanish Ministry of Science predoctoral fellowship (Formación de Personal Investigador, PRE2020–092011) to Rosaria M. Zangri.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Rosaria Maria Zangri contributed to the study design, data collection, data analysis, and first draft of the manuscript, as well as subsequent revisions; Pablo Roca contributed to the data collection, data analysis, and manuscript writing; Ivan Blanco contributed to the study design, coordination of data collection, and data visualization; Marta Kulis contributed to the study design and data collection; Gustavo G. Diez contributed to the study design and data collection; Jose Ignacio Martin-Subero contributed to the study design and data collection; Carmelo Vázquez contributed to the study design, data collection, supervision of data analysis, funding acquisition, and manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the University Complutense’s Ethics Committee (Ref. 22/449-E, July 2022), being conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zangri, R.M., Roca, P., Blanco, I. et al. Psychological Changes Following MBSR and CCT Interventions in a Brief and Intensive Retreat Format: A Sequential Randomized Crossover Study. Mindfulness 15, 1896–1912 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02410-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-024-02410-w