Abstract

Objectives

During the pandemic, establishing effective interventions to mitigate burnout is essential to ensure the provision of stable healthcare. This study examined the efficacy of a 4-week online mindfulness program on healthcare workers’ burnout to explore whether brief online programs can influence healthcare workers’ wellbeing by decreasing signs and symptoms of burnout.

Methods

We examined differences between healthcare workers’ burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment) at three time points (baseline, post-intervention, and follow-up survey) using linear regression analyses accounting and without accounting for covariates. Covariates included demographic (age, sex), work-related (year of work experience, mode of care), resiliency (the ability to bounce back from hardship), and mindfulness-related factors (number of practices per week, prior experience of mindfulness, number of sessions attended). A total of n = 130 healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada, participated in the study (October 2020 to March 2021).

Results

Without accounting for the covariates, the two components of burnout, emotional exhaustion (feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one’s work) and depersonalization (an unfeeling and impersonal response toward recipients of one’s service, care, treatment, or instruction) levels, were significantly lower after the 4-week mindfulness program compared to the baseline and remained lower after 4 weeks. However, the personal accomplishment level (feelings of competence and achievement in one’s work) remained unchanged after the mindfulness program. Resiliency significantly contributed to reducing emotional exhaustion. Number of mindfulness practices contributed to reducing emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and enhancing personal accomplishment.

Conclusions

The findings provide a basis for healthcare organizational development decision-makers to consider employee-facing mindfulness programs. It also informs curriculum designers of mindfulness education and training programs to create online programs for maximum efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Healthcare workers are at high risk of burnout (Chen et al., 2013; Dreison et al., 2018; Happell et al., 2003; Morse et al., 2012). During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers’ risk of burnout is heightened due to long hours, increased workload, and increased psychological stressors (De Kock et al., 2021). Burnout in healthcare workers is associated with mental and physical health problems and a diminished sense of wellbeing, including increased depression, anxiety, sleep problems, impaired memory, neck and back pain, and alcohol consumption (Chen et al., 2013). Burnout in healthcare workers also endangers the availability, stability, and quality of patient care (Leo et al., 2021). In addition to the negative impact on patient care, burnout incurs greater absenteeism and intentions to quit (Morse et al., 2012), a phenomenon plaguing the healthcare field, endangering healthcare stability during subsequent waves and post-pandemic recovery (Sandhu et al., 2022). Not surprisingly, stress has mounted during the pandemic, whereby 1 in 5 healthcare workers reported experiencing depression and anxiety-related symptoms (Pappa et al., 2020). Long hours, increased workload, and increased psychological stress such as anxiety, depression, and burnout have reduced healthcare workers' quality of life (QOL) (De Kock et al., 2021). The prevalence of severe healthcare worker burnout continues to mount, with the most recent Spring 2021 rates indicating that > 60% of Canadian physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals were experiencing burnout (Tuite et al., 2021). As the pandemic persists, healthcare workers have less control over their deployment and decision-making, reducing their sense of self-efficacy and impacting their ability to cope with stress.

Burnout is characterized as feeling emotional exhaustion (feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one’s work), depersonalization (an unfeeling and impersonal response toward recipients of one’s service, care, treatment, or instruction), and reduced personal accomplishment (feelings of competence and achievement in one’s work) (Maslach et al., 1996). Although burnout is understood as a state of being, burnout and wellbeing are not binary; instead, they are better understood as coexisting along a continuum. Stress is inevitable, and wellbeing is achieved when individuals can move between a state of risk, anxiety, or adversity and safety and calmness (Nagoski & Nagoski, 2020). The goal is not to stay in a state of safety and calm but to skillfully navigate through stress and achieve balance, much like returning to homeostasis. Evidence suggests that resiliency, or the ability to “bounce back” after stress, can decrease the likelihood of burnout (Maunder et al., 2008). Research on resilience and burnout has long suggested that stress is not the problem and that people cannot avoid or eradicate stress altogether. We know from previous mass traumas that resiliency is vital for our society to recover from the pandemic (Heymann & Shindo, 2020; Polizzi et al., 2020; Shaw, 2020; Smith et al., 2020). Previous studies indicate that existing psychological problems, COVID-related trauma, and interpersonal avoidance in the workplace and personal life increase the risk for burnout (Lasalvia et al., 2021). Furthermore, work-related factors such as long shifts and redeployments, especially among healthcare workers (Tan et al., 2020), and patient-facing roles related to the fear of COVID-19 exposure (Prasad et al., 2021) were significantly associated with burnout. Among the demographic factors, female sex and young age (< 30 years) were associated with burnout (Gramaglia et al., 2021). Accordingly, understanding factors contributing to burnout and establishing effective support, programs, and interventions to boost healthcare worker wellbeing and mitigate burnout is warranted (Djalante et al., 2020). Specifically, programs that develop strong coping skills and resilience may support healthcare workers in moving through stress.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are a validated educational approach to building coping skills and resilience. With over two decades of mounting scientific research demonstrating benefits — from fortifying the immune system to reducing stress and anxiety and improving overall wellbeing — MBIs have been used to mitigate emotional challenges (Brady et al., 2012; Cohen-Katz et al., 2005; Ireland et al., 2017). Secular mindfulness is a practice that involves focusing awareness on the present moment while acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations without judgment (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Mindfulness programs teach skills to cultivate awareness and practice non-judgment and promote connectedness that can be used to build resilience (Behan, 2020; Polizzi et al., 2020). Empathetic communication skills are taught in many MBIs and have been found to decrease physician burnout and increase wellbeing (Wagaman et al., 2015). Accordingly, MBIs have been recommended to mitigate healthcare workers’ burnout and promote wellbeing during the pandemic (Amanullah & Ramesh Shankar, 2020; Sultana et al., 2020) and are effective in reducing burnout among healthcare professionals and students (Bodini et al., 2022; Klatt et al., 2020; Luberto et al., 2020; Marotta et al., 2022; Osman et al., 2021).

The most commonly used MBI in healthcare is the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program (MBSR) (Irving et al., 2009; Lamothe et al., 2016). Initially developed as a stress management tool, it is now used to treat, support, or prevent various health-related disorders. MBSR consists of pre-program orientation (2.5/hr), one 2.5–3.5 hr per week class, typically delivered weekly for 8 weeks with one full-day (7.5 hr) retreat. In addition, participants are asked to dedicate 45 min to formal practice and 5–15 min to homework daily, 6 days per week, for the duration of the program. Participants receive training in traditional mindfulness meditation techniques, including body scan, body awareness and mindful movement, walking and sitting meditation, and informal practices such as breath awareness. Although validated with rich evidence of efficacy, this program requires a robust time commitment of approximately 74.5 hr. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) combines MBSR with cognitive behavior therapy to support relapse prevention treatment for individuals with a high likelihood of recurring depression. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Life (MBCT-L), an adapted version for the general population, needs to be more researched, and more evidence is needed to compare it against MBSR programs (Alsubaie et al., 2017; Jasbi et al., 2018). Although proven highly effective, COVID-19 rendered in-person MSBR and MBCT delivery nearly impossible, and healthcare workers’ schedules and the challenges of rolling closures and lockdowns restricted their time and availability.

Studies exploring abbreviated MBSR found similar results to the full-length program, suggesting that significant improvements can still be made with reduced session time (Frank et al., 2015; Osman et al., 2021; Pérula-de Torres et al., 2021). A briefer program, the Mindfulness Ambassador Program (MAP), consists of twelve 60-min learning sessions and integrates brief formal practices, most of which can be completed in 5–10 min within and outside of the 60-min learning session. Still, in the early stages, two studies were conducted in Canada using MAP (MacDougall et al., 2019; Smith-Carrier et al., 2015), suggesting a positive impact on stress reduction, relaxation, social awareness, and relationship building among adolescents (Smith-Carrier et al., 2015), and in decreasing depression and fatigue among early psychosis patients (MacDougall et al., 2019).

While mindfulness has shown promise to mitigate burnout in healthcare workers during the pandemic (Klatt et al., 2020; Luberto et al., 2020; Marotta et al., 2022; Osman et al., 2021), most studies have been based on lengthy, face-to-face programs. Furthermore, most studies so far did not consider healthcare workers’ work- (e.g., year of work experience, mode of care) and mindfulness-related factors (e.g., prior experience of mindfulness, number of sessions attended) that may impact the efficacy of the mindfulness program. Lastly, whether the effect is maintained after the program concludes is rarely investigated. Accordingly, this study investigated the effectiveness of a brief, online mindfulness program and its maintenance effect. The mindfulness program was tailored to meet the unique needs of healthcare workers amid the pandemic in reducing burnout by increasing access and geographical reach through online synchronous delivery of “brief” or bit-sized educational programs (four 30-min sessions). The study also accounted for and explored the association of demographic (age, sex), work-related (year of work experience, mode of care), resiliency, and mindfulness-related (number of practices completed outside of the learning session per week, prior experience with mindfulness, number of sessions attended) factors on burnout.

Method

Participants

The role of the 4-week online Mindfulness Ambassador Program (MAP, developed by a non-profit organization, Mindfulness Without Borders), in healthcare workers’ burnout during the pandemic was examined. A total of 130 healthcare workers in Ontario, Canada, participated in the study through a frontline wellness program at a psychiatric hospital (age < 30 = 17.05%, 31–50 = 53.8%, > 50 = 28.68%; female = 93%). Of the healthcare workers participating in the 4-week online mindfulness program, 58% completed mindfulness practices 1–3 times a week. 8.5% of healthcare workers never practiced mindfulness, and 42% practiced almost daily. 53% of the healthcare workers provided direct (in-person) care during the pandemic. Of the healthcare workers, 54% were 31 to 50 years old, 28% were over 51 years old, and 18% were less than 30 years old; 55% of the healthcare workers completed all four sessions, 23% completed three, and 17% completed two sessions. Slightly more than a third (36%) of the healthcare workers had participated in mindfulness programs before.

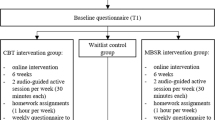

Procedure

The 4-week online Mindfulness Ambassador Program (MAP) was offered to healthcare workers via Zoom through the institutions’ frontline wellness program (October 2020 to March 2021). Since the pandemic, MAP was retooled, making it shorter and available online to help combat practitioners’ likelihood of burnout. The revamped program consisted of weekly 30-min self-care sessions and included the introduction of a formal mindfulness skill a healthcare worker could use immediately to reduce stress. The skills taught within the program were intentionally brief and could be practiced in 5–10 min. Retooling the MAP program morphed a face-to-face, 12-week, and 12-hr program into a virtual, 4-week, 2-hr skill-based course, emphasizing brief skills that could be practiced in 5–10 min. Participants were invited to use the brief practices shared as often as possible, ideally once daily.

In this retooling, the program shifted from a dialogue-based social-emotional learning program into a less robust, more succinct program focused on presenting and modeling mindful-awareness-based strategies, including formal mindfulness skills such as anchoring with breath (the 3-min breath and five-finger breath), anchoring with external stimuli (mindful listening), and mind–body awareness (body scan), and essential mindfulness mindsets, including paying attention and connecting authentically, to help individuals strengthen wellbeing, act with compassion, and develop resilience. Each session began with a check-in using an emotions thermometer (Brackett, 2019) to help participants access their wisdom (i.e., emotional awareness) and that of the group. Each session included a closing takeaway self-care practice recommendation (e.g., practice anchor breath). Participants had access to online prerecorded mindful practices during and after the condensed MAP to help support continued practice. The program was delivered synchronously, and although less dialogical, there were still opportunities for participants to share and connect. The integrity of the mindfulness component was maintained through the introduction and modeling of the MAP’s core mindfulness practices (Table 1).

After obtaining consent, a pre-survey was given before the program began. Each mindfulness session ran once a week for 30 min, with one certified MAP facilitator assigned to each group (maximum 20). A post-survey was administered immediately after the fourth session, with a follow-up survey 1 month after the last session. After the post and follow-up survey, participants were offered a $20 gift card as an honorarium for their time. Surveys for this quantitative component were conducted and completed online.

Measures

Participant Characteristics

Demographic information, including age groups, sex assigned at birth, years worked in the healthcare setting, and mode of care, was collected during the pre-survey. Participant age group was categorized into three groups “less than 30,” “31–50 years old,” or “more than 50 years old.” Participant sex assigned at birth was dichotomized as “male” or “female,” respectively. The number of years worked in a healthcare setting was categorized into three groups: “less than 11 years,” “11 to 20 years,” and “more than 20 years.” Healthcare workers caring for patients directly (face to face) were categorized as “Direct Care,” and those healthcare workers providing virtual care and non-clinical support (e.g., administrative, IT, or research) were categorized as “Indirect Care.” Several mindfulness-related variables, including the number of MAP sessions attended, mindfulness experience, and the number of mindfulness practices in a week following each session, were measured. Any mindfulness-related experience, regardless of length, frequency, platform (online or offline), or type of mindfulness-based programs, was indicated as “yes.” Number of mindfulness practices was categorized into three groups: “never,” “1 to 3 times a week,” and “4 to 7 times a week.”

Burnout

Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey- (MBI-HSS) (Maslach et al., 1996) is a 22-item scale to measure 3-dimensional aspects of professional burnout in human service. Three components are (1) emotional exhaustion (EE) — feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one’s work; (2) depersonalization (DP) — an unfeeling and impersonal response toward recipients of one’s service, care, treatment, or instruction; and (3) personal accomplishment (PA) — feelings of competence and achievement in one’s work. Based on the MBI manual, scores higher than 27 (EE), 13 (DP), and less than 31 (PA) are categorized as high levels; scores 17–26 (EE), 7–12 (DP), and 38–32 (PA) as moderate, and less than 16 (EE), 6 (DP), and more than 39 (PA) as low levels. MBI presented good reliability, both using omega and alpha coefficients. Using omega as a reliability estimator, MBI achieved acceptable reliability for all 3 factors above the usually recommended value of 0.70 (Aguayo-Estremera et al., 2023; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1978). Cronbach alpha ratings of 0.90 for emotional exhaustion, 0.76 for Depersonalization, and 0.76 for personal accomplishment were reported (Iwanicki and Schwab, 1981; Maslach et al., 1996).

Resilience

Nicholson McBride’s Resilience Questionnaire (Clarke & Nicholson, 2010) is a 12-item survey with Likert-type responses designed to measure resilience, defined as one’s capacity to bounce back from extreme occasions or triumph in the face of hardship, which was used to measure resiliency. Scores ranged from 12 to 60, where higher numbers indicate greater resilience. The scores are further categorized into developing (0–37), established (38–43), strong (44–48), and exceptional (49–60) levels. An established level of resilience would indicate that you may occasionally have tough days when things do not go your way, and an exceptional level of resilience indicates that you are very resilient most of the time and rarely fail to bounce back, whatever life throws at you. The reliability estimated by Cronbach’s alpha is 0.76 (Murphy, 2014).

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics and proportions were reported for all variables included in the model to inform the sample characteristics. Differences between burnout outcomes (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, personal accomplishment) during three time points (baseline, post-intervention, and follow-up survey; panel data) were examined using linear regression analyses applying the generalized least squares (GLS) approach. Linear regression analysis allows us to understand the relationship between the independent variables (i.e., predictors) and dependent variables (i.e., outcome) while accounting for covariates (Ali & Younas, 2021). GLS is an extension of generalized linear models for panel (longitudinal) data that estimates more efficient and unbiased regression parameters (Ballinger, 2004; Hardin, 2005). GLS adjusts the standard errors and produces efficient estimates of the coefficients by considering the over-time correlations when producing the coefficient estimates. First, an unadjusted regression model was conducted to examine the change in three components of burnout (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment) over time (baseline, post-intervention, and 1-month follow-up after completing the mindfulness program). Next, other variables such as participant characteristics (age, sex), healthcare worker’s role (clinical, non-clinical), work location (front line or virtual/online), years of occupational service, and mindfulness-related variables such as previous exposure to mindfulness program (Yes/No), the number of sessions attended, and the frequency of mindfulness practice, and resiliency were added to the model (adjusted model). Coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. Software for Statistics and Data Science (STATA) (V.16.0) was used.

Results

Table 2 describes the percentages of burnout subcategories of healthcare workers during the pandemic at baseline (pre-intervention). Almost half of our healthcare workers (46.2%) felt high emotional exhaustion. Despite high emotional exhaustion, most healthcare workers felt personally accomplished nonetheless and did not show depersonalization, which may indicate a significant commitment to their role in caring for a vulnerable population. The average emotional exhaustion score (26.15) fell at the high end of the moderate category (17–26). Depersonalization (6.21) was categorized as moderate level (6–9), and personal accomplishment (34.9) was moderate (32–38).

Table 3 describes the participant demographics, and Table 4 presents burnout and resilience scores on pre-, post-, and follow-up surveys. Of the participants, 54% were between 31 and 50 years old, and 93% were females. Half of the participants (50%) worked in healthcare settings for less than 11 years, and similar proportions of the participants cared for the patients face to face (53%) and indirectly (46%). Most participants completed half of the mindfulness sessions and had previously participated in other mindfulness programs (37%). Slightly less than two thirds (64%) of the participants practiced mindfulness one to three times per week after the sessions.

Without accounting for covariates, the emotional exhaustion level was significantly lower after the 4-week mindfulness program compared to the baseline (reference) (β = − 1.83, 95% CI = − 3.46 to − 0.21, p < 0.05). The emotional exhaustion level remained lower at the follow-up survey (4 weeks after the completion of the MAP) compared to the baseline (β = − 3.18, 95% CI = − 5.40 to − 0.97, p < 0.01). Likewise, the depersonalization level was significantly lower after the 4-week mindfulness program compared to the baseline (β = − 0.83, 95% CI = − 1.56 to − 0.09, p < 0.05). The depersonalization level remained lower at follow-up (β = − 1.05, 95% CI = − 2.06 to − 0.03, p < 0.05). However, the personal accomplishment level remained unchanged after the mindfulness program and after 4 weeks of completion of the program.

Table 5 shows the relationship between burnout and mindfulness intervention accounting for covariates such as demographic (age, sex, years worked, and mode of care) factors and mindfulness-related factors (mindfulness experience, mindfulness practice, number of sessions attended) and resiliency. The emotional exhaustion level decreased after the mindfulness program compared to the baseline. Furthermore, the emotional exhaustion level decreased significantly at an alpha level of 0.01 at follow-up (β = − 4.59, 95% CI = − 7.39 to − 1.78, p < 0.01). This finding suggests that regardless of the demographic and mindfulness-related factors, a 4-week online mindfulness program effectively reduces emotional exhaustion, and the effect remains at follow-up. MAP practice (1–3 times/week) (β = − 8.59, 95% CI = − 16.29 to − 0.29, p < 0.05) and strong resiliency (β = − 7.63, 95% CI = − 12.95 to − 2.30, p < 0.01) and exceptional resiliency (β = − 11.58, 95% CI = − 17.51 to − 5.65, p < 0.001) were significantly and negatively associated with emotional exhaustion, indicating that practicing mindfulness frequently after the session and the capacity to bounce back from hardship contribute in reducing emotional exhaustion. Controlling for demographic factors and resilience, we see that the depersonalization and personal accomplishment level were unchanged after the mindfulness program compared to the baseline, meaning that depersonalization (e.g., cynicism) is explained by covariates included in the model. For example, depersonalization was significantly lower for those who practiced mindfulness 4–7 times/week than those who never practiced mindfulness after the session (β = − 3.87, 95% CI = − 7.17 to − 0.57, p < 0.05). Female sex was significantly and positively associated with depersonalization (β = 4.42, 95% CI = 1.29 to 7.55, p < 0.01), meaning that female healthcare workers tend to have higher depersonalization levels than male counterparts. MAP practice 4–7 times/week significantly contributed to increasing personal accomplishment (β = 6.65, 95% CI = 2.37 to 10.93, p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study evaluated the efficacy of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention in mitigating burnout in healthcare workers during high stress (amid the COVID pandemic). Our findings demonstrated a reduction in two components of burnout (i.e., levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) immediately after the mindfulness program compared to the baseline levels, and these effects were maintained after 4 weeks of the program completion. The ability to bounce back after hardship (i.e., resiliency) also significantly contributed to decreasing emotional exhaustion. Lastly, practicing mindfulness after the session effectively contributed to all three components of burnout in healthcare workers during the pandemic.

Our findings align with previous studies that show a positive impact in reducing burnout in healthcare workers during the pandemic (Klatt et al., 2020; Marotta et al., 2022; Osman et al., 2021). For instance, Marotta et al. (2022) found significant reductions in emotional exhaustion and an increase in depersonalization after the in-person MBSR courses in healthcare workers but observed no significant changes in professional efficacy. Similarly, Klatt et al. (2020) reported significant reductions in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and an increase in professional efficacy in healthcare professionals using an in-person, 8-week Mindfulness in Motion program. Moreover, a recent study investigating the efficacy of a brief online mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (four 1-hr sessions) in healthcare workers is most comparable to the current research (Osman et al., 2021). The authors report a significant reduction in emotional exhaustion and an increased accomplishment immediately after the program, while depersonalization remained the same. The lengthier sessions in this study (Osman et al., 2021) may have created more space for participants to consider, practice, and develop the skills being taught. Furthermore, the additional time for dialogue may have allowed them the opportunity to consider the skills and practices in relation to their professional identity in the presence of other healthcare workers. Compared to these recent studies, our findings showed no significant improvement in personal accomplishments. In our study, females were more susceptible to depersonalization. Those individuals with more than 20 years of work experience in the healthcare field had reduced depersonalization, suggesting that the practices taught within the program may have different impacts at various times amid the lifecycle of a healthcare worker. The healthcare workers who participated in the current study felt moderate levels of accomplishment at baseline. We speculate that mindfulness can mitigate exacerbated burnout but has a limited impact on improving personal accomplishment beyond a moderate level.

Overall, based on the current study, we report comparable effects (i.e., improvement in emotional exhaustion and depersonalization) on healthcare workers’ burnout with a much shorter mindfulness program provided online during the pandemic for healthcare workers. We found that the number of mindfulness practices and level of resiliency are significantly associated with reducing emotional exhaustion, confirming resiliency’s positive impact on burnout (Maunder et al., 2008). Furthermore, frequent mindfulness practice helps increase personal accomplishment and reduce depersonalization. Participants who dedicated time to practice were likely to integrate the strategies taught into their daily life, a practice that reaffirms the skills taught.

Our study is unique in several aspects. First, we used linear regression models using the GLS approach that produces efficient and accurate estimates of the coefficients by considering the over-time correlations. Second, we adjusted for mindfulness and work-related factors such as the number of mindfulness practices, resiliency, and mode of care (direct vs. indirect care) in the model and examined their association with burnout. Third, we examined the maintenance effect after 4 weeks of the program completion. Last, the current study was conducted (October 2020 to March 2021) when only 11.3% received the vaccine, and the Gamma variant was rapidly spreading with serious health outcomes increasing the medical burden in Canada (Desson et al., 2020; Detsky & Bogoch, 2020; Public Health Ontario, 2020).

Burnout in healthcare workers is associated with mental and physical health problems and a diminished sense of wellbeing, including increased depression, anxiety, sleep problems, impaired memory, neck and back pain, and alcohol consumption (Chen et al., 2013). The factors contributing to burnout in healthcare workers amid the pandemic are complex, with professional and personal elements influencing wellbeing. A recent meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research specific to mental health workers indicates that reducing burnout in this sector is more complex than in other occupations, even considering different stressful environments and job instability (Dreison et al., 2018). Providing a brief online MBI to promote psychological wellbeing and mitigate psychological distress such as burnout may be a viable means of meeting the needs of healthcare workers who do not have time or available means to seek out clinical support and services. The current findings will support the use of brief online mindfulness programs in reducing healthcare workers’ burnout and subsequently address human resource challenges in the healthcare system. A brief online mindfulness program may be helpful for more challenging-to-reach populations such as geographically diverse and rural communities, work environments with difficulties in providing in-person instruction, and to meet the varied availability of shift workers who juggle caregiving, academic, and professional responsibilities.

There is a growing interest in creating accessible strategies for healthcare workers to promote better mental health and resiliency. Based on the results of this study, expanding brief online MBIs to a broader audience is critical, including strategizing ways to meet the needs of those experiencing burnout. The efficacy of brief online MBIs delivered asynchronously should also be explored to increase access to healthcare workers in underserved areas, including those serving in areas without high-speed internet. The outcome of this study responds to the critical need to cultivate a resilient society amid a global pandemic (Heymann & Shindo, 2020; Polizzi et al., 2020; Shaw, 2020; Smith et al., 2020). Lessons learned can also guide corporate wellness programming through physical distancing and beyond as we slowly transition to a “new normal.” Administrators and decision-makers within healthcare and systems where employees are subject to high stress and burnout should consider implementing brief online mindfulness and social-emotional learning programs.

Limitations and Future Research

Our study has limitations, including the absence of a randomized control group, a relatively homogeneous sample of female healthcare workers, and a lack of information on race/ethnicity, limiting the generalization of findings. Future studies should include broader groups of healthcare workers and use a more robust study design. It is also important to recognize the more considerable systemic limitation to research on burnout. Many burnout prevention programs, such as the MBI examined in this study, place the burden of work on individuals. For example, many healthcare workers completed this program on their own time, either during their lunch break or at home after work. The structural issues contributing to burnout include workload, work-life balance, staff shortages, systemic discrimination such as racism, contract, precarious work, and lack of affordable/reliable daycare which should also be considered. There is a likelihood that practitioners needing support and seeking resiliency-based training were not able to partake due to structural inequities such as not having child care, working a double day, precarious work, and staffing shortages. The institutional culture was not assessed in this study. Future studies need to dissect healthcare work culture to ensure that mindfulness initiatives do not mask systemic issues or toxic work culture. Despite the limitations, our findings uniquely add to the current literature highlighting the comparable efficacy of brief online mindfulness-based programs in reducing burnout in healthcare workers during the pandemic.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Aguayo-Estremera, R., Cañadas, G. R., Ortega-Campos, E., Ariza, T., & De la Fuente-Solana, E. I. (2023). Validity Evidence for the Internal Structure of the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Student Survey: A Comparison between Classical CFA Model and the ESEM and the Bifactor Models. Mathematics, 11(6), 1515. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11061515

Ali, P., & Younas, A. (2021). Understanding and interpreting regression analysis. Evidence Based Nursing, 24(4), 116–118. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2021-103425

Alsubaie, M., et al. (2017). Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 55, 74–91.

Amanullah, S., & Ramesh Shankar, R. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: A review. Healthcare, 8(4), 421. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040421

Ballinger, G. A. (2004). Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 7(2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8040421

Behan, C. (2020). The benefits of Meditation and Mindfulness practices during times of crisis such as Covid-19. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(4), 256–258. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2020.38

Bodini, L., Bonetto, C., Cheli, S., Del Piccolo, L., Rimondini, M., Rossi, A., Carta, A., Porru, S., Amaddeo, F., & Lasalvia, A. (2022). Effectiveness of a Mindful Compassion Care Program in reducing burnout and psychological distress amongst frontline hospital nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 23(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-022-06666-2

Brackett, M. (2019). Permission to feel: Unlocking the power of emotions to help our kids, ourselves, and our society thrive. Celadon Books.

Brady, S., O’Connor, N., Burgermeister, D., & Hanson, P. (2012). The impact of mindfulness meditation in promoting a culture of safety on an acute psychiatric unit. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 48(3), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2011.00315.x

Chen, K.-Y., Yang, C.-M., Lien, C.-H., Chiou, H.-Y., Lin, M.-R., Chang, H.-R., & Chiu, W.-T. (2013). Burnout, job satisfaction, and medical malpractice among physicians. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 10(11), 1471–1478. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.6743

Clarke, J., & Nicholson, J. (2010). Resilience: bounce back from whatever life throws at you. Hachette UK.

Cohen-Katz, J., Wiley, S. D., Capuano, T., Baker, D. M., & Shapiro, S. (2005). The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout, Part II: A quantitative and qualitative study. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004650-200501000-00008

De Kock, J. H., Latham, H. A., Leslie, S. J., Grindle, M., Munoz, S.-A., Ellis, L., Polson, R., & O’Malley, C. M. (2021). A rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of healthcare workers: Implications for supporting psychological wellbeing. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-10070-3

Desson, Z., Weller, E., McMeekin, P., & Ammi, M. (2020). An analysis of the policy responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in France, Belgium, and Canada. Health Policy and Technology, 9(4), 430–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.09.002

Detsky, A. S., & Bogoch, I. I. (2020). COVID-19 in Canada: Experience and response. JAMA, 324(8), 743–744. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.14033

Djalante, R., Shaw, R., & De Wit, A. (2020). Building resilience against biological hazards and pandemics: COVID-19 and its implications for the Sendai Framework. Progress in Disaster Science, 6, 100080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100080

Dreison, K. C., Luther, L., Bonfils, K. A., Sliter, M. T., McGrew, J. H., & Salyers, M. P. (2018). Job burnout in mental health providers: A meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000047

Frank, J. L., Reibel, D., Broderick, P., Cantrell, T., & Metz, S. (2015). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction on educator stress and wellbeing: Results from a pilot study. Mindfulness, 6(2), 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0246-2

Gramaglia, C., Marangon, D., Azzolina, D., Guerriero, C., Lorenzini, L., Probo, M., Rudoni, M., Gambaro, E., & Zeppegno, P. (2021). The mental health impact of 2019-nCOVID on healthcare workers from North-Eastern Piedmont, Italy. Focus on burnout. Frontiers in public health, 9, 667379. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.667379

Happell, B., Martin, T., & Pinikahana, J. (2003). Burnout and job satisfaction: A comparative study of psychiatric nurses from forensic and a mainstream mental health service. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00267.x

Hardin, J. W. (2005). Generalized estimating equations (GEE). Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470013192.bsa250

Heymann, D. L., & Shindo, N. (2020). COVID-19: What is next for public health? The Lancet, 395(10224), 542–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30374-3

Ireland, M. J., Clough, B., Gill, K., Langan, F., O’Connor, A., & Spencer, L. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness to reduce stress and burnout among intern medical practitioners. Medical Teacher, 39(4), 409–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2017.1294749

Irving, J. A., Dobkin, P. L., & Park, J. (2009). Cultivating mindfulness in health care professionals: A review of empirical studies of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 15(2), 61–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.01.002

Iwanicki, E. F., & Schwab, R. L. (1981). A cross validation study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 41(4), 1167–1174. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316448104100425

Jasbi, M., et al. (2018). Influence of adjuvant mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans–results from a randomized control study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(5), 431–446.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Klatt, M. D., Bawa, R., Gabram, O., Blake, A., Steinberg, B., Westrick, A., & Holliday, S. (2020). Embracing change: A mindful medical center meets COVID-19. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 9, 2164956120975369. https://doi.org/10.1177/2164956120975369

Lamothe, M., Rondeau, É., Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Duval, M., & Sultan, S. (2016). Outcomes of MBSR or MBSR-based interventions in health care providers: A systematic review with a focus on empathy and emotional competencies. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 24, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2015.11.001

Lasalvia, A., Amaddeo, F., Porru, S., Carta, A., Tardivo, S., Bovo, C., Ruggeri, M., & Bonetto, C. (2021). Levels of burn-out among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated factors: a cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital of a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. BMJ Open, 11(1), e045127. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045127

Leo, C. G., Sabina, S., Tumolo, M. R., Bodini, A., Ponzini, G., Sabato, E., & Mincarone, P. (2021). Burnout among healthcare workers in the COVID 19 era: a review of the existing literature. Frontiers in public health, 9, 750529. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.750529

Luberto, C. M., Goodman, J. H., Halvorson, B., Wang, A., & Haramati, A. (2020). Stress and coping among health professions students during COVID-19: A perspective on the benefits of mindfulness. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 9, 2164956120977827. https://doi.org/10.1177/2164956120977827

MacDougall, A. G., Price, E., Vandermeer, M. R., Lloyd, C., Bird, R., Sethi, R., Shanmugalingam, A., Carr, J., Anderson, K. K., & Norman, R. M. (2019). Youth-focused group mindfulness-based intervention in individuals with early psychosis: A randomized pilot feasibility study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 13(4), 993–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12753

Marotta, M., Gorini, F., Parlanti, A., Berti, S., & Vassalle, C. (2022). Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on the Wellbeing, Burnout and Stress of Italian Healthcare Professionals during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(11), 3136. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11113136

Maslach C., Jackson S. E., & Leiter M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maunder, R. G., Leszcz, M., Savage, D., Adam, M. A., Peladeau, N., Romano, D., Rose, M., & Schulman, R. B. (2008). Applying the lessons of SARS to pandemic influenza. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 99(6), 486–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03403782

Morse, G., Salyers, M. P., Rollins, A. L., Monroe-DeVita, M., & Pfahler, C. (2012). Burnout in mental health services: A review of the problem and its remediation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(5), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-011-0352-1

Murphy, Y. (2014). The role of job satisfaction, resilience, optimism and emotional intelligence in the prediction of burnout (Bachelors final year project). Dublin Business School, Ireland. Diperoleh dari. https://esource.dbs.ie/handle/10788/2276

Nagoski, E., & Nagoski, A. (2020). Burnout: The secret to unlocking the stress cycle. Ballantine Books.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. (1978). Psychometric testing. McGraw-Hill.

Osman, I., Hamid, S., & Singaram, V. S. (2021). Efficacy of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention on the psychological wellbeing of health care professionals and trainees during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed method design. Health SA Gesondheid (online), 26, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v26i0.1682

Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3594632

Pérula-de Torres, L. Á., Verdes-Montenegro-Atalaya, J. C., Melús-Palazón, E., García-de Vinuesa, L., Valverde, F. J., Rodríguez, L. A., Lietor-Villajos, N., Bartolomé-Moreno, C., Moreno-Martos, H., & García-Campayo, J. (2021). Comparison of the effectiveness of an abbreviated program versus a standard program in mindfulness, self-compassion and self-perceived empathy in tutors and resident intern specialists of family and community medicine and nursing in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084340

Polizzi, C., Lynn, S. J., & Perry, A. (2020). Stress and coping in the time of COVID-19: pathways to resilience and recovery. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 17(2), 59–62. https://doi.org/10.36131/CN20200204

Prasad, K., McLoughlin, C., Stillman, M., Poplau, S., Goelz, E., Taylor, S., Nankivil, N., Brown, R., Linzer, M., & Cappelucci, K. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of stress and burnout among US healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national cross-sectional survey study. EClinicalMedicine, 35, 100879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879

Public Health Ontario. (2020). Enhanced Epidemiological Summary: COVID-19 in Ontario: a summary of wave 1 transmission patterns and case identification. Public Health Ontario.

Sandhu, H. S., Smith, R. W., Jarvis, T., O’Neill, M., Di Ruggiero, E., Schwartz, R., Rosella, L. C., Allin, S., & Pinto, A. D. (2022). Early Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Public Health Systems and Practice in 3 Canadian Provinces From the Perspective of Public Health Leaders: A Qualitative Study. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 28(6), 702–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000001596

Shaw, S. C. (2020). Hopelessness, helplessness and resilience: The importance of safeguarding our trainees’ mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurse Education in Practice, 44, 102780. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102780

Smith, G. D., Ng, F., & Li, W. H. C. (2020). COVID-19: Emerging compassion, courage and resilience in the face of misinformation and adversity. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(9–10), 1425–1428. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15231

Smith-Carrier, T., Koffler, T., Mishna, F., Wallwork, A., Daciuk, J., & Zeger, J. (2015). Putting your mind at ease: Findings from the Mindfulness Ambassador Council programme in Toronto area schools. Journal of Children’s Services, 10(4), 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1108/jcs-10-2014-0046

Sultana, A., Sharma, R., Hossain, M. M., Bhattacharya, S., & Purohit, N. (2020). Burnout among healthcare providers during COVID-19: Challenges and evidence-based interventions. Indian J Med Ethics, 5(4), 308–311. https://doi.org/10.20529/ijme.2020.73

Tan, B. Y., Kanneganti, A., Lim, L. J., Tan, M., Chua, Y. X., Tan, L., Sia, C. H., Denning, M., Goh, E. T., & Purkayastha, S. (2020). Burnout and associated factors among health care workers in Singapore during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(12), 1751–175. e81755. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.035

Tuite, A. R., Fisman, D. N., Odutayo, A., Bobos, P., Allen, V., Bogoch, I., Allen, V., Bogoch, I. I., Brown, A. D., Evans, G. A., Greenberg, A., Hopkins, J., Maltsev, A., Manuel, D. G., McGeer, A., Morris, A. M., Mubareka, S., Munshi, L., Murty, V. K., ..., Jüni P. on behalf of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table. (2021). COVID-19 hospitalizations, ICU admissions and deaths associated with the new variants of concern. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table, 1(18), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.18.1.0

Wagaman, M. A., Geiger, J. M., Shockley, C., & Segal, E. A. (2015). The role of empathy in burnout, compassion satisfaction, and secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 60(3), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swv014

Acknowledgements

We thank Fariha Chowdhury and Nadine Proulx for conducting a literature review, Nicole Adams for her support in data collection, and Nicole Mace for her support in tailoring the mindfulness program, and promoting and implementing the mindfulness program for healthcare workers through a frontline wellness program. We also thank Mindfulness Without Borders for their support in retooling the mindfulness program and Georgian College for their help in the study. Most importantly, we thank all the healthcare workers and facilitators who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by a College and Community Innovation Program- Applied Research Rapid Response to COVID-19 Grant funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (Award # COVPJ 554453–20).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors: conceptualization. Soyeon Kim: data curation, writing—original draft preparation, quantitative data analysis. Sarah Hunter: critical revisions, writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent To Participate

All data collection, analysis, and dissemination protocols were reviewed and approved by the Waypoint Centre for Mental Healthcare’s ethics review board (Protocol ref. # HPRA#20.07.27).

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants for anonymized participant information to be published in this article.

Conflict of Interest

Soyeon Kim declares no conflict of interest. During the data collection period, Sarah Hunter worked with Mindfulness Without Border (MWB), facilitating mindfulness programs for other institutions. Sarah Hunter was no longer in contract with MWB during the manuscript preparation period.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Hunter, S. Can Brief Online Mindfulness Programs Mitigate Healthcare Workers’ Burnout amid the COVID-19 Pandemic?. Mindfulness 14, 1930–1939 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02175-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02175-8