Abstract

Objectives

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on health, economy, and social networks had an impact on the whole population’s mental health, including students. The study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief online mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care intervention for medical students.

Methods

A randomized controlled trial was conducted with medical students (n=360) from a Chilean university with no prior meditation experience. An online assessment of well-being, anxiety, and depression symptoms was completed at the beginning, 1 month, and 3 months later. A general intervention (GI) was offered to the whole group including academic flexibility, breaks, and individual psychological help. For specific intervention, enrolled participants (n=120) were randomly assigned to (1) mindfulness-based inter-care intervention (IBAP, n=60) or (2) psychoeducational intervention (PSE, n=60) as an active control. Both interventions lasted 1 hr per week along 4 weeks, with homework assignments. The non-randomized third group (n=240) received only the GI, as a treatment-as-usual control group (TAU-GI).

Results

At baseline, IBAP and PSE groups had higher scores in depression symptoms than TAU-GI. IBAP and TAU-GI showed a significant reduction in depression (F(2)=17.44, p<0.001) and anxiety symptoms (F(2)=18.06, p<0.001), but not for the PSE group at first and 3 months. Compared to TAU-GI, IBAP showed a substantial reduction in depression symptoms at first month (U=24.89, p<0.05). An analysis of secondary variables showed improvements in the factors of mental health continuum and common humanity on the Self-Compassion Scale.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that brief online mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care intervention, with academic flexibility and break, effectively promoted mental health among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Preregistration

The protocol was enrolled in Clinicaltrial.gov with protocol ID NCT05011955.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, along with the different measures adopted by governments such as lockdowns, social distancing, and restricted mobility, has led to financial and social consequences around the globe. Moreover, mental health has also been adversely compromised. For instance, a systematic review of depression symptoms across different countries shows a higher prevalence than anticipated from previous years before the pandemic (14.6 to 48.3%). Additionally, the pandemic has been associated with acute stress syndrome, insomnia, and emotional exhaustion (Brooks et al., 2020). Risk factors included younger age, unemployment, retirement, low educational level, and student status (Fernández et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020).

Even before the pandemic, medical students reported higher levels of anxiety symptoms (33.8%) (Tian-Ci Quek et al., 2019), depressive symptomatology (27.2%), suicidal thoughts (11.1%) (Rotenstein et al., 2016), stress level, burnout, and substance abuse compared to the general population (Molodynski et al., 2021). However, due to the pandemic, students may experience higher levels of stress, loneliness, anxiety, and depression symptoms because of the isolation, limited social interaction, lack of emotional support, and physical contact. Additionally, uncertainty and concerns about family health may also contribute to these symptoms (Elmer et al., 2020). Specifically, in a study of 40 medicine faculties in the USA, 30.6% and 24.3% of medicine students reported positive anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively (Halperin et al., 2021). In Chile, the high presence of both symptoms in a local faculty of medicine was also reported (Villalón et al., 2022). Due to this reason, there has been a growing interest in the mental health and well-being of college students. This situation has promoted preventive measures in universities to minimize the impact of psychological stress, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. One such intervention, for instance, involves mindfulness and compassion techniques (González-García et al., 2021).

In recent years, there has been an increase in interest in mindfulness-based interventions (MBI), which have been studied in different populations, conditions, and programs (Goldberg et al., 2017; Lomas et al., 2018). Mindfulness has been defined as a process of attention regulation to bring a quality of non-elaborative awareness to current experience, within a curiosity, experiential openness, and acceptance orientation (Bishop, 2004), and as a method to foster alternative responses to stress and emotional distress. Potential mechanisms of change through meditation practice, involving attention regulation, body awareness, and emotional and self-regulation, have also been discussed (Tang et al., 2015).

The first-generation programs of MBI consist of eight weekly face-to-face group sessions lasting 2 hr each, along with a full day of practice, meditation logs, and journaling exercises as homework. The most common standardized MBIs are mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, 2012) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Segal et al., 2012). Before the pandemic, a study examined the use of 8 weeks of MBSR with medical students and reported acceptable results up to 20 weeks post-intervention (van Dijk et al., 2017). Morr et al. (2020) also reported moderate results in their randomized controlled trial for an 8-week mindfulness-based virtual community program. Furthermore, a study that used a 6-week MBSR adaptation reported no differences between the treatment and control group (Damião Neto et al., 2020).

In response to criticisms regarding instrumentalization, second-generation programs such as Cognitively-based Compassion Training and Compassion Cultivation Training have been proposed (Gonzalez-Hernandez et al., 2019; Van Gordon et al., 2015). This program may also enhance well-being, mental health, and pro-social behavior. Recently, a study examined the feasibility of a brief 7-hr asynchronous online mindfulness and compassion program in first-year psychology students during COVID-19 lockdown with promising results (González-García et al., 2021). Additionally, in scenarios where there is a lack of time for participants or providers, or limited resources, traditional MBSR implementation may be challenging; however, brief interventions could be feasible options. For instance, a four-session MBSR has similar effect sizes to longer versions (Demarzo et al., 2017), as have online adaptations (González-García et al., 2021; Kemper & Rao, 2017). However, there is no clear evidence about the effectiveness of brief MBIs lasting fewer than 4 h in reducing anxiety and stress in health professionals (Gilmartin et al., 2017; Howarth et al., 2019; McClintock et al., 2019).

Finally, criticisms have been proposed regarding the representation of mindfulness practices in various contexts. For example, there is an overrepresentation of the developed world and an underrepresentation of Latin America. Additionally, concerns have been raised about the representation of ethics and/or spirituality, considering the current diversity, potential barriers, and the need for the integration of intercultural and spiritual competencies (Hernández-Torrano et al., 2020; Villalón, 2023). Furthermore, a secular approach to MBI recognizes the importance of ethics despite the absence of explicit content and that participants/instructor bring their own ethical rules. In any case, the individualized process can generate variability in the effectiveness of mindfulness practice, so the possibility of guiding the process has been recommended (Krägeloh, 2016). Based on this and considering the ethical aspects of medical care, an approach is proposed both of self-care and others-care, that is, an inter-care.

Care is a main part of medical practice and can be defined as “commitment with heart, concern, paying attention, dedicate to something,” and can distinguish the care as (1) for life, (2) for human flourishing, and (3) therapeutic. It can be represented by indicators of care behavior such as attending, listening, being there with the word, the intention of comprehension, empathy, and compassion (Mortari, 2019). This proposal defines the recognition of needs for care and communication as relevant aspects of a care theoretical approach. Based on this approach and inspired by first- and second-generation mindfulness-based interventions, the mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care program (IBAP) was developed. Some specific exercises of the program include compassionate communication, reflection on one’s own values and purpose, gratitude practices, and active cultivation of shared resources such as social bonds (Villalón, In Press)

This research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a brief 4-week online mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care intervention in medical students to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

Participants

A population of 498 medical students from first to seventh year of the Medicine Faculty of the Diego Portales University in Santiago, Chile, were invited to voluntarily participate through institutional email to respond to an online survey from April to August 2020. All students received the general intervention (GI) during the study period.

Three hundred and sixty responses (n=360) were received (response rate 72%). All respondents with interest in the specific intervention trial (n=120) were randomly included in a mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care intervention (IBAP, n=60) as an intervention group or in a psychoeducation-based intervention (PSE, n=60) as an active control group. Randomization was conducted using a random-number table. Students were not aware of their group allocation until all participants had completed the online baseline assessment. The remaining 240 participants who were not interested in the specific intervention trial but were interested in participating in the follow-up cohort group received the general intervention only as part of the treatment-as-usual control group (TAU-GI). Demographic and year characteristics can be found in Table 1 and a CONSORT flow diagram in Fig. 1.

Procedure

In response to the crisis during the pandemic and periods of lockdown, the Faculty of Medicine established a mental health committee composed of faculty, administrators, and students to evaluate and implement mental health support measures. The main goals were to assess the impact of the pandemic on mental health of medicine students, implement general organizational and educational interventions for whole student body, and provide specific interventions for student in need. The study was planned and conducted within this context.

A non-blinded randomized controlled trial was conducted between April and November 2020, with assessments at the beginning of the study, post-intervention 1 month later, and a follow-up 3 months later.

All assessments were done through an electronic survey platform, guaranteeing confidentiality. The survey included questions on demographic characteristic, as well as validated questionnaires about depressive and anxiety symptoms, mental health, mindfulness, and self-compassion variables (details in the “Measures” section), and were completed by participants at the beginning, post-intervention, and 3-months follow-up.

General intervention (GI), academic breaks of 2 weeks per semester (apart from holidays), and academic flexibility in submitting work, attending practical activities, and examination dated were offered to the student body.

Four to eight individual counseling sessions were offered if they reported a high score on depression or anxiety symptoms, and, if necessary, were then referred to continue mental health services in the university student’s welfare system and/or in the respective personal insurance health system. Participants who were not willing to participate in the specific intervention trial were considered part of the treatment-as-usual group and received only the general intervention (TAU-GI).

Mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care intervention, the intervention was a brief version of the mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care program or intercuidado basado en atención plena y compasión in Spanish (IBAP) (Villalón, In Press). It consists of four weekly synchronic group sessions via Zoom of 1 hr each and home practice. A total of four groups, 15 students each, were conducted by one certified mindfulness teacher. The IBAP program is based on the care theoretical approach (Mortari, 2019) and was inspired by first- and second-generation mindfulness-based interventions, such as mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, and Cognitively-based Compassion Training. The program focuses on actively cultivating inter-care resource, including recognizing care needs for oneself, others, and the community; training in compassionate communication skills; reflection on one’s own values; and purpose and planning mutual care resource.

Each module consists of meditation practices, inquiry, and self- or group-reflections on topics such as mindfulness, automatic pilot, mind wandering, acceptance, gratitude and compassion, care resources, and inter-care. The summary of modules and components is available in Table 2.

Psychoeducational intervention (PSE), the PSE intervention was designed for this study. It consists of four synchronic group sessions via Zoom of 1 hr each, one per week, and home practice. A total of four groups were conducted with 15 students each. Two psychologists facilitated these interventions.

The objective of the intervention was to develop the following self-care habits and skills: (1) time management, (2) stress management, (3) effective communication, and (4) health habits such as exercise, sleep hygiene, and diet.

Measures

The primary outcomes were depression and anxiety symptoms scales. Secondary variables were gender, university level, mental health, mindfulness, and self-compassion traits.

Depression symptoms were evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ9), which is used for depression screening with a sensibility and specificity of 88% and 92%. It contains 9 items on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4) to evaluate frequency of symptoms from Never to Almost every day. It has been translated and validated in Spanish and Chilean populations (Baader et al., 2012; Saldivia et al., 2019). The cut-off points are 5, 10, 15, and 20 for mild, moderate, moderate-severe, and severe depression symptoms. McDonald’s omega reliability estimate for the PHQ9 is 0.9, indicating high reliability.

Anxiety symptoms were evaluated using the General Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) validated in Spain (García-Campayo et al., 2010) for anxiety disorder screening with a sensitivity and specificity of 86.8% and 93.4%. It contains 7 items on a 5-point Likert scale (0–3) to evaluate frequency of symptoms from Never to Almost every day. The cut-off points are 5, 10, and 15 for mild, moderate, and severe anxiety symptoms. A high level of reliability is indicated by McDonald’s omega reliability estimate of 0.94 for the GAD-7.

Mental health can be defined as a state in which an individual realizes their own abilities, can cope with the stresses of life, can work productively, and can make a positive contribution to society. Keyes (2002) describes mental health in 3 main dimensions: emotional, psychological well-being, and social well-being. Keyes developed the Mental Health Continuum Scale-Long Form (MHC-LF) composed of 40 items. In 2009, Keyes developed a shorter 14-item version which was translated and validated in Chilean adults in 2017 by Guadalupe Echeverría et al. (2017). The MHC-14 dimensions showed high reliability with McDonald’s omega estimates of ω=0.87 for emotional well-being, ω=0.85 for social well-being, and ω=0.91 for psychological well-being.

Mindfulness is defined as the ability to pay attention to our own experiences without judging them, and recently, it has been incorporated into many programs for the treatment of recurrent depressive and anxiety disorders. Baer et al. (2006) developed the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), which consists of 39 questions that examine 5 facets of mindfulness: observe, describe, act aware, non-judge, and non-react. A 15-item version was validated in Chile in 2021 by Villalón et al. (In Press). The FFMQ-15 has acceptable reliability with Cronbach’s alpha estimates of 0.86 for non-react, 0.79 for act aware, 0.68 for describe, 0.76 for non-judge, and 0.73 for observe.

Self-compassion is understood as maintaining full attention and opening without disconnecting from self’s suffering with the desire to alleviate pain in a non-judgmental way, comprehending the own experience as a part of the human experience. Evidence describes that those with higher self-compassion present fewer points in anxiety and depression symptoms (Germer & Neff, 2019; Neff, 2003; Neff et al., 2007). A scale with 6 subdomains was developed by Neff (2003) and for this study, a translation of the “Self-Compassion Scale Short Form – 12” was made according to the Ramadilla-Rodilla proposed method (Ramada-Rodilla et al., 2013). The Spanish 12-item version was validated in Chile in 2021 by Villalón et al. (in press). Neither Cronbach’s alpha nor a reported reliability estimate was provided, as it is a 2-item scale.

Data Analyses

Since all variables showed a non-normal distribution, as assessed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test (p<0.001 on all variables), and due to small samples and unequal sample sizes, non-parametric analyses were conducted (Nwobi & Akanno, 2021; Skovlund & Fenstad, 2001).

For continuous variables, medians were compared; the Kruskal-Wallis (H) test was used for independent samples and Friedman test (F) for dependent samples. Post hoc analyses were made using the Dunn test with Bonferroni correction (Z). To assess baseline differences, we compared pre-post differences between groups (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). Size effect was calculated using Kendall’s coefficient of concordance (W) (Tomczak & Tomczak, 2014). For nominal variables, χ2 tests were used. A Monte Carlo simulation was used as an alternative when the conditions for a χ2 test were not met. To manage missing data, a nearest neighbor imputation was made, and then a sensitivity analysis was conducted (Beretta & Santaniello, 2016). Analyses were performed on IBM SPSS 25 and RStudio.

The hypotheses in the study were (1) the IBAP, PSE, and TAU-GI as interventions are effective in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety in medical students over time. (2) The IBAP intervention is more effective in reducing anxiety and depression compared to PSE and TAU-GI.

Results

Of a total of 498 medical students, 360 completed the first assessment (72% response rate), 205 the second assessment 1 month later (43% dropout), and 127 3 months later (65% dropout). Response rate and dropout of each group and time are reported in Table 3. There were significant lower dropout rates in IBAP and PSE at first month (χ2(2) = 19.41, p <0.001) and IBAP in third month (χ2(2) = 11.82, p =0.003) compared to TAU-GI.

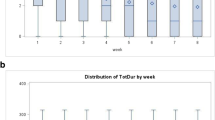

There are differences between school year distribution between three groups (χ2(12) = 112.95, p <0.001, Monte Carlo p <0.001 CI 0.000–0.000) and no gender differences (χ2(4) = 7.68, p=0.103). Demographics and differences are exposed on Table 1 and medians for primary outcomes (Mdn) on Table 4 and Fig. 2. A Kruskal-Wallis test showed that at baseline there are significant differences between the three groups in depression and anxiety symptoms (H(2)= 13.32, p <0.001). Participants in IBAP and PSE group show higher depression (Mdn=13.5 and 13) and anxiety symptoms (Mdn=10 and 11) than TAU-GI (Mdn=10 and 8). A post hoc Dunn-Bonferroni test using a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level was used to compare all pairs of groups. The difference in depression symptoms between IBAP/TAU-GI (Z = −47.79, IBAP (n = 59), TAU-GI (n = 256), p <0.001) and PSE/TAU-GI (Z= −38.5, PSE (n=45), TAU-GI (n= 256), p=0.022) was significant. Only IBAP/TAU-GI difference was maintained after Bonferroni adjustment (p = 0.004). There is no difference between IBAP and PSE at baseline.

Intervention Efficacy

A Friedman test was performed for each group in time. For IBAP, it showed the time affects depression (F(2)= 17.44, p<0.001) and anxiety symptoms (F(2)= 18.06, p<0.001). Effect size were W=0.26 and W=0.27. At first month (Mdn=9 and 6) and third month (Mdn=8 and 6), participants showed lower depression and anxiety symptoms than baseline (Mdn= 13.5 and 10). Post hoc Dunn’s test using a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level was used to compare all pairs of groups. The difference in depression symptoms between baseline-first month (z=0.82, p=0.001) and baseline-third month (z=0.86, p=0.001) was significant and it was maintained after Bonferroni adjustment (p=0.001 and p=0.003). The difference in anxiety symptoms between baseline-first month (z=0.85, p=0.000) and baseline-third month (z=0.92, p=0.001) was significant and it was maintained after Bonferroni adjustment (p.=0.001 and p.=0.002). Similar results were found for TAU-GI. There is no significant difference in anxiety or depression symptoms after Bonferroni adjustment at any time for PSE group. Results including size effect (W) can be found in Table 5.

The Kruskal-Wallis test showed that studied arms significantly affect at first month changes in depression (H(2)= 6.26, p=0.044) and anxiety symptoms (H(2)= 6.08, p=0.044). Participants in the IBAP group show higher symptoms reduction (Mdn=−4.0 and −3.0) than PSE (Mdn=−2.5 and −1.0) or TAU-GI (Mdn=−1.0 and −1.0). A post hoc test showed that the difference in depression symptoms changes between IBAP and TAU-GI was significant (U=24.89, IBAP (n=42), TAU-GI (n=127), p=0.016), and it was maintained after Bonferroni adjustment (p=0.049). For anxiety symptoms, the post hoc test showed a difference between IBAP and TAU-GI (U=22.34, IBAP (n=42), TAU-GI (n=127), p=0.031), and IBAP and PSE (U= −29.58, IBAP (n=42), PSE (n=36), p=0.025). None of the other comparisons were significant after Bonferroni adjustment (all p>0.05) (Table 6).

Attrition Analysis

Attrition analysis shows differences between groups at first month (χ2(2) = 19.45, p=0.001) and third month (χ2(2) = 11.82, p=0.003). Post hoc analysis shows less dropout rate at first month in PSE (standardized residual (SR) = −2.3) and IBAP (SR= −1.6), and in third month in IBAP (SR= −1.9). Dropout rates are in Table 3. There is a difference between participants who dropped out the study year at first month for gender (χ2(2) = 7.37, p = 0.025) and school year (χ2(6) = 33.88, p=0.001), and third month only for school year (χ2(6) = 29.83, p=0.001). At first month, males (SR=1.5), 5th (SR=1.7), 6th (SR=1.4), and 7th (SR=2.1) grade had higher dropout rates. At third month, 6th (SR=2.0) and 7th (SR=1.6) grade had higher dropout rates.

After conducting a nearest neighbor imputation sensitivity analysis on the completed data, similar results as before were obtained. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed that the studied intervention arms significantly affected changes in depression (H(2)= 15.16, p<0.001) and anxiety symptoms (H(2)= 12.70, p=0.002) at the first month. Post hoc tests, with Bonferroni adjustment, revealed significant differences in depression symptom changes between the IBAP and TAU-GI groups (p<0.001), as well as in anxiety changes between the IBAP and TAU-GI groups (p=0.006) and between the IBAP and PSE groups (p=0.02).

Effects on Secondary Variables

A Friedman test was conducted to analyze the secondary variables in the IBAP group. Significant changes were observed in EWB (F(2) = 7.26, p=0.026), SWB (F(2) = 9.07, p=0.011), and the common humanity factor of the SCS (F(2) = 14.3, p=0.001). None of the other secondary variables was found to be significant. At baseline, there were no differences between the PSE and IBAP groups in these variables (p>0.05). The Mann-Whitney U test revealed a significant difference only in the common humanity factor of the SCS at the third month compared to the PSE group (p=0.021).

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to evaluate the effectiveness on depression, anxiety symptoms, and well-being of a brief online mindfulness- and compassion-based inter-care intervention for medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Overall, the results showed that a brief 4-hr IBAP intervention, combined with a general intervention consisting of academic breaks and flexibility, was effective in reducing anxiety and depression symptoms both at the end of the intervention and at the 3-month follow-up. Compared to both control groups, there were significant changes in anxiety at 1 month, and in depression only compared to TAU-GI. Also, there are important effects of academic flexibility, breaks, and other possible factors as shown in the treatment-as-usual general intervention group. The intervention also had an impact on secondary variables, such as the common humanity factor of the Self-Compassion Scale, as well as emotional and social well-being.

Based on this, the results of this study support the effectiveness of brief 4-hr mindfulness- and compassion-based interventions for medical students, along with the use of organizational interventions. The baseline differences between the IBAP/PSE groups compared to TAU-GI may be explained by the selection method. Participants who perceive themselves as having a higher burden, fewer resilience resources, and a greater desire for support may have enrolled for randomization in the specific intervention study to receive additional support beyond the general intervention. Regarding the groups with a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms, IBAP could accelerate the reduction of symptomatology. It has previously been reported that organizational interventions associated with groups or individuals have greater effectiveness and the possibility of maintaining the change over time in health professionals (Wiederhold et al., 2018). It may be feasible to offer this kind of intervention specifically for those with higher burdens, in addition to organizational interventions.

The high dropout rate of this study in the three groups stands out. Although the mindfulness-based intervention had a lower dropout rate, it was close to 50%. At the same time, the participation in the workshops was higher than the survey response rate. There are several possible factors that explain this, such as the high academic demand, the stress caused by the pandemic, and laxity in reviewing the institutional mail or survey mail that arrives in a spam folder. Also, during the study period, there were two studies taking place at the same time with the same population; one of them had two main surveys, which may have led to exhaustion in answering surveys or confusion between the studies. Unfortunately, the other investigation did not individualized responses, making it impossible to cross-reference the databases. Nevertheless, future studies should evaluate the reasons for dropout and assess maintenance incentives, considering that participation was voluntary and outside of the academic curriculum. Similar studies with lower dropout rates have incorporated the intervention into the curriculum (Damião Neto et al., 2020; van Dijk et al., 2017) or have offered financial incentives or academic benefits (Morr et al., 2020). Although, we must consider that mandatory activities can be less effective for mental health (Damião Neto et al., 2020).

Another relevant point is effect on self-compassion. The results show an increase of common humanity as a factor of self-compassion. Previous studies describe an increase in the Self-Compassion Scale in 16-hr or short 7-hr programs, but it was not broken down by factors (González-García et al., 2021; Jazaieri et al., 2013). Regarding the SCS-12 scale used in the study, it has been described that it presents better psychometric properties when using the six-factor model (Villalón et al., In press).

In relation to previous studies, there is no clear evidence that mindfulness- and compassion-based interventions are effective for medical students, as there have been contradictory findings. For instance, some studies have reported that the classical MBSR program of 8 weeks was effective for clinical clerkship students, with positive effects lasting up to 20 months post-intervention (van Dijk et al., 2017). However, other studies suggest that compulsory, large-group 6-week modified student programs have no effect, even though this intervention was mandatory (Damião Neto et al., 2020). Our results suggest that a voluntary intervention, in addition to organizational support, may be effective for a specific group. It is important to consider that this intervention may not be suitable for everyone, but for those who are in greater need of help. Furthermore, more evidence is needed for brief interventions, especially during the COVID-19 crisis. However, as reviewed, to date, there is no clear evidence of the effectiveness of brief mindfulness interventions over time, nor is there a standardized definition of “brief.” Nevertheless, interventions lasting more than 4 hr have been found to be effective at reducing anxiety symptomatology (Gilmartin et al., 2017; Howarth et al., 2019; McClintock et al., 2019). Brief interventions are important in the context of limited time or resources. During the COVID-19 pandemic, such interventions can offer a rapid response in addition to other organizational interventions. For instance, an 8-week mindfulness-based community online intervention has been reported to be effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression (Morr et al., 2020), as well as a brief online intervention through videos totaling 7 hr plus exercises at home (González-García et al., 2021). Nonetheless, randomized controlled trials are still needed. Our results support previous evidence that a brief online intervention may be effective in reducing anxiety and depression.

To our knowledge, this is the first study during the COVID-19 pandemic that uses a randomized controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy on a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Considering access to the entire population of students at the Diego Portales University and a high initial response rate, the participants are a representative sample. At the same time, having randomization with a control group that also received an intervention of the same duration allowed us to distinguish common factors that are related to the intervention, such as the Hawthorne effect and group support.

The implication of this study is that a brief online mindfulness- and compassion-based intervention of 4 hr, in addition to organizational interventions, may be effective in reducing anxiety or depression symptoms during a critical situation. Furthermore, in case of limited resources, this intervention could be targeted towards those with higher levels of symptomatology.

Limitations and Future Directions

The data must be interpreted with caution given the high rate of dropout of the sample during follow-up, sample size, and the notion that the same team that carried out the workshops was the one who was asked to answer the survey. This can influence positive responses, particularly in MBI (Davidson & Kaszniak, 2015). Future research is necessary to replicate this study. We recommend including an extended version of the intervention, such as a standard 8-week mindfulness intervention, a larger sample size, and multicenter evaluation with different instructors, assessing more participants and incorporating a more comprehensive follow-up to ensure more robust results and generalizability of findings. Additionally, surveys to collect and analyze results with blinded assessment should be considered.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to them containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants. However, the authors are committed to making the data available to interested researchers in a responsible and transparent manner, in compliance with all relevant ethical and legal requirements.

References

Baader, T. M., Molina, F. J. L., Venezian, S. B., Rojas, C. C., Farías, R. S., Fierro-Freixenet, C., Backenstrass, M., & Mundt, C. (2012). Validación y utilidad de la encuesta PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) en el diagnóstico de depresión en pacientes usuarios de atención primaria en Chile. Revista chilena de neuro-psiquiatría, 50(1), 10–22. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92272012000100002

Beretta, L., & Santaniello, A. (2016). Nearest neighbor imputation algorithms: A critical evaluation. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 16(3), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0318-z

Bishop, S. R. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph077

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Wadsworth.

Damião Neto, A., Lucchetti, A. L. G., da Silva Ezequiel, O., & Lucchetti, G. (2020). Effects of a required large-group mindfulness meditation course on first-year medical students’ mental health and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(3), 672–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05284-0

Davidson, R. J., & Kaszniak, A. W. (2015). Conceptual and methodological issues in research on mindfulness and meditation. American Psychologist, 70(7), 581–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039512

Demarzo, M., Montero-Marin, J., Puebla-Guedea, M., Navarro-Gil, M., Herrera-Mercadal, P., Moreno-González, S., Calvo-Carrión, S., Bafaluy-Franch, L., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2017). Efficacy of 8- and 4-session mindfulness-based interventions in a non-clinical population: A controlled study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01343

Duan, W., & Li, J. (2016). Distinguishing dispositional and cultivated forms of mindfulness: Item-level factor analysis of Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire and construction of Short Inventory of Mindfulness Capability. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01348

Echeverría, G., Torres, M., & Pedrals, N. (2017). Validation of a Spanish version of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form Questionnaire. Psicothema, 29(1), 96–102. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2016.3

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., & Stadtfeld, C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PloS ONE, 15(7), e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Fernández, R. S., Crivelli, L., Guimet, N. M., Allegri, R. F., & Pedreira, M. E. (2020). Psychological distress associated with COVID-19 quarantine: Latent profile analysis, outcome prediction and mediation analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 75–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.133

García-Campayo, J., Zamorano, E., Ruiz, M. A., Pardo, A., Pérez-Páramo, M., López-Gómez, V., Freire, O., & Rejas, J. (2010). Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8, 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-8

Germer, C., & Neff, K. (2019). Mindful self-compassion (MSC). In I. Ivtzan (Ed.), Handbook of mindfulness-based programmes (1st ed., pp. 357–367). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315265438-28

Gilmartin, H., Goyal, A., Hamati, M. C., Mann, J., Saint, S., & Chopra, V. (2017). Brief mindfulness practices for healthcare providers—A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Medicine, 130(10), 1219.e1–1219.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.05.041

Goldberg, S. B., Tucker, R. P., Greene, P. A., Davidson, R. J., Wampold, B. E., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

González-García, M., Álvarez, J. C., Pérez, E. Z., Fernandez-Carriba, S., & López, J. G. (2021). Feasibility of a brief online mindfulness and compassion-based intervention to promote mental health among university students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mindfulness, 12(7), 1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01632-6

Gonzalez-Hernandez, E, Harrison, T, & Fernandez-Carriba, S. (2019). CBCT®: A program of Cognitively-Based Compassion. In Laura Galiana & Noemi Sanso (Eds.), The Power of Compassion. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Halperin, S. J., Henderson, M. N., Prenner, S., & Grauer, J. N. (2021). Prevalence of anxiety and depression among medical students during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 8, 238212052199115. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120521991150

Hernández-Torrano, D., Ibrayeva, L., Sparks, J., Lim, N., Clementi, A., Almukhambetova, A., Nurtayev, Y., & Muratkyzy, A. (2020). Mental health and well-being of university students: A bibliometric mapping of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01226

Howarth, A., Smith, J. G., Perkins-Porras, L., & Ussher, M. (2019). Effects of brief mindfulness-based interventions on health-related outcomes: A systematic review. Mindfulness, 10(10), 1957–1968. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01163-1

Jazaieri, H., Jinpa, G. T., McGonigal, K., Rosenberg, E. L., Finkelstein, J., Simon-Thomas, E., Cullen, M., Doty, J. R., Gross, J. J., & Goldin, P. R. (2013). Enhancing compassion: A randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1113–1126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9373-z

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2012). Vivir con plenitud las crisis: Cómo utilizar la sabiduría del cuerpo y de la mente para afrontar el estrés, el dolor y la enfermedad. In Programa de la Clínica de Reducción del Estrés del Centro Médico de la Universidad de Massachusetts. Editorial Kairós.

Kemper, K. J., & Rao, N. (2017). Brief online focused attention meditation training: Immediate impact. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(3), 395–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587216663565

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Krägeloh, C. U. (2016). Importance of morality in mindfulness practice. Counseling and Values, 61(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/cvj.12028

Lomas, T., Medina, J. C., Ivtzan, I., Rupprecht, S., & Eiroa-Orosa, F. J. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions in the workplace: An inclusive systematic review and meta-analysis of their impact upon wellbeing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(5), 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1519588

McClintock, A. S., McCarrick, S. M., Garland, E. L., Zeidan, F., & Zgierska, A. E. (2019). Brief mindfulness-based interventions for acute and chronic pain: A systematic review. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(3), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0351

Molodynski, A., Lewis, T., Kadhum, M., Farrell, S. M., Lemtiri Chelieh, M., Falcão De Almeida, T., Masri, R., Kar, A., Volpe, U., Moir, F., Torales, J., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Chau, S. W. H., Wilkes, C., & Bhugra, D. (2021). Cultural variations in wellbeing, burnout and substance use amongst medical students in twelve countries. International Review of Psychiatry, 33(1-2), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2020.1738064

Morr, C. E., Ritvo, P., Ahmad, F., Moineddin, R., & Team MVC. (2020). Effectiveness of an 8-week web-based mindfulness virtual community intervention for university students on symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 7(7), e18595. https://doi.org/10.2196/18595

Mortari, L. (2019). Filosofia del Cuidado (1st ed.). Editorial Universidad del Desarrollo.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.03.004

Nwobi, F., & Akanno, F. (2021). Power comparison of ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis tests when error assumptions are violated. Advances in Methodology and Statistics, 18(2), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.51936/ltgt2135

Ramada-Rodilla, J. M., Serra-Pujadas, C., & Delclós-Clanchet, G. L. (2013). Adaptación cultural y validación de cuestionarios de salud: Revisión y recomendaciones metodológicas. Salud Pública de México, 55(1), 57–66.

Rotenstein, L. S., Ramos, M. A., Torre, M., Segal, J. B., Peluso, M. J., Guille, C., Sen, S., & Mata, D. A. (2016). Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 316(21), 2214–2236. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17324

Saldivia, S., Aslan, J., Cova, F., Vicente, B., Inostroza, C., Rincón, P., Saldivia, S., Aslan, J., Cova, F., Vicente, B., Inostroza, C., & Rincón, P. (2019). Propiedades psicométricas del PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire) en centros de atención primaria de Chile. Revista médica de Chile, 147(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872019000100053

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., Teasdale, J. D., & Kabat-Zinn, J. (2012). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Skovlund, E., & Fenstad, G. U. (2001). Should we always choose a nonparametric test when comparing two apparently nonnormal distributions? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 54(1), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00264-X

Tang, Y.-Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916

Tian-Ci Quek, T., Wai-San Tam, W., X. Tran, B., Zhang, M., Zhang, Z., Su-Hui Ho, C., & Chun-Man Ho, R. (2019). The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(15), 2735. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16152735

Tomczak, M., & Tomczak, E. (2014). The need to report effect size estimates revisited. An overview of some recommended measures of effect size. Trends in Sport Sciences, 1(21),19–25.

van Dijk, I., Lucassen, P. L. B. J., Akkermans, R. P., van Engelen, B. G. M., van Weel, C., & Speckens, A. E. M. (2017). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on the mental health of clinical clerkship students: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Academic Medicine, 92(7), 1012–1021. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001546

Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Towards a second generation of mindfulness-based interventions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(7), 591–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415577437

Villalón, F. J., Cerda, M. I. M., Venegas, W. G., Amaro, A. A. S., & Campos, J. V. A. (2022). Presencia de síntomas de ansiedad y depresión en estudiantes de medicina durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Revista Médica de Chile, 150(8), 1018–1025. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0034-98872022000801018

Villalón, F. J. (2023). Mindfulness, compasión e intercuidado: Su marco conceptual. Pinelatinoamericana, 3(1), 42–53. https://revistas.unc.edu.ar/index.php/pinelatam/article/view/40756

Villalón, F. J. (In Press). Mindfulness, compasión e intercuidado: El programa de Inter cuidado basado en atención Plena (IBAP). Pinelatinoamericana, 3(2).

Villalón, F., Escaffi, M., & Correa, M. E. (In press). Validación de la escala Self Compassion Scale Short Form en profesionales y estudiantes de medicina en Chile. Revista Médica de Chile.

Villalón, F., Mundt, A., & Escaffi, M. (In Press). Validación de la escala Five Facets of Mindfulness Short Form en estudiantes y profesionales de medicina en Chile. Revista Médica de Chile.

Wang, Z.-H., Yang, H.-L., Yang, Y.-Q., Liu, D., Li, Z.-H., Zhang, X.-R., Zhang, Y.-J., Shen, D., Chen, P.-L., Song, W.-Q., Wang, X.-M., Wu, X.-B., Yang, X.-F., & Mao, C. (2020). Prevalence of anxiety and depression symptom, and the demands for psychological knowledge and interventions in college students during COVID-19 epidemic: A large cross-sectional study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.034

Wiederhold, B. K., Cipresso, P., Pizzioli, D., Wiederhold, M., & Riva, G. (2018). Intervention for physician burnout: A systematic review. Open Medicine, 13, 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1515/med-2018-0039

Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Francisco J. Villalón L: study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis. Writing — original draft preparation. Writing — review and editing. Methodology. Formal analysis and investigation. Williams Venegas Gonzalez: writing — original draft preparation. Writing — review and editing. Javiera Arancibia: writing — original draft preparation. Writing — review and editing. Formal analysis and investigation. Adrian Soto: writing — original draft preparation. Writing — review and editing. Formal analysis and investigation. Maria Ivonne Moreno: formal analysis and investigation. Supervision. Rita Rivera: writing — review and editing. Alfredo Pemjean: writing — review and editing. Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Statement

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of University Diego Portales University in Santiago, Chile (N 06-2020) on May 14, 2020. The protocol was enrolled in Clinicaltrial.gov with protocol ID NCT05011955.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent and consent to publish were obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Villalón, F.J., Moreno, M.I., Rivera, R. et al. Brief Online Mindfulness- and Compassion-Based Inter-Care Program for Students During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Mindfulness 14, 1918–1929 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02159-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02159-8