Abstract

Objectives

This experience sampling study examined the roles of trait self-compassion in everyday self-control. Specifically, this study examined whether trait self-compassion influences people’s self-efficacy in handling difficult self-control demands, and subsequently, their self-control success.

Method

The participants were asked to respond to five random signals per day for seven consecutive days. When responding to each signal, they first indicated if they had exerted self-control over the past 30 min and, if yes, reported their momentary self-control experiences such as perceived difficulty, self-efficacy, and success. Trait self-compassion was measured 1 week before the experience sampling phase. A total of 1725 self-control episodes from 115 college students were analyzed.

Results

No main effects of trait self-compassion on self-control difficulty, self-efficacy, and success were observed. Nevertheless, trait self-compassion interacted with perceived difficulty in predicting self-efficacy. Specifically, perceived difficulty was associated with reduced self-efficacy, only among individuals low in trait self-compassion.

Conclusions

Self-compassionate people appeared to be better at protecting self-efficacy when dealing with difficult self-control tasks. The findings provide nuanced views on how trait self-compassion may be beneficial to self-control in everyday life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Self-compassion is associated with a wide range of positive psychological outcomes (for a recent review, see Bluth and Neff 2018; Ferrari et al. 2019). Although past studies suggested that self-compassion improves self-control (e.g., Hallion et al. 2019; Kelly et al. 2010), little has been known about the mechanisms that underlie the effects of trait self-compassion on momentary self-control outcomes. Moreover, past studies primarily focused on health-related domains. The impact of trait self-compassion on self-control in other life domains was seldom tested.

According to Neff (2003), self-compassion consists of three interrelated components: (a) being kind and understanding to one’s suffering, (b) recognizing one’s vulnerability as part of the universal human condition, and (c) recognizing and accepting one’s present experience, whether it is positive or negative. The past 17 years of research has consistently found that self-compassion is beneficial to psychological well-being (e.g., Blanden et al. 2018; Marshall et al. 2015) and physical health (e.g., Brion et al. 2014; Ceccarelli et al. 2019).

In general, a self-control behavior involves prioritizing a long-term goal when it competes with a less desirable short-term goal (Fujita 2011). It sometimes includes impulse control such that people need to override dominant responses and align their behaviors with long-term goals (Baumeister et al. 2007). Successful self-control is critical to goal pursuit and well-being (Daly et al. 2015; De Ridder et al. 2018).

Despite its appeal, sustaining self-control can be very difficult (Baumeister and Vohs 2007; Duckworth and Seligman 2017; Heatherton and Tice 1994). During self-control, people have to focus on the long-term goal pursuit rather than shift to immediate hedonic goals (Inzlicht and Schmeichel 2012; Molden et al. 2016). Moreover, a difficult self-control task can undermine self-efficacy, which in turn, impairs self-control performance (Chow et al. 2015).

Past research has demonstrated the facilitative effect of trait self-compassion on self-control performance. Trait self-compassion is positively associated with successful self-control in the health domain such as healthy eating (Homan and Sirois 2017; Mantzios et al. 2015), exercising (Semenchuk et al. 2018), reduced bedtime procrastination (Sirois et al. 2019), and medical adherence (Brion et al. 2014). A recent review further suggested that self-compassion intervention is comparable with other theory-based interventions on self-control outcomes (Biber and Ellis 2019). For example, Kelly et al. (2010) found that a self-compassion intervention reduced cigarette smoking more than a self-monitoring intervention and was comparable with a self-control intervention that emphasized effortful inhibition.

Nevertheless, how trait self-compassion facilitates momentary self-control performance remains underexplored. It is likely that trait self-compassion protects self-efficacy when handling difficult tasks. Self-efficacy refers to “judgment of how well one can execute courses of action required to deal with prospective situations” (Bandura 1982, p.122). There is some indirect evidence regarding the association between self-compassion and self-efficacy. First, Gilbert (2005, 2009) suggested that self-compassionate thoughts stimulate the soothing-affiliation system in the brain in a way that is similar to the presence of warm, supportive, compassionate others. As encouragement and support from others can boost self-efficacy (Bandura 1997; Usher and Pajares 2006), self-compassionate thoughts can make people feel supported and self-efficacious when handling demanding tasks.

Second, difficult tasks often trigger aversive feelings like frustration and fear of failure (Saunders et al. 2015), resulting in additional demand for emotion regulation. Nevertheless, self-compassion reduces these regulatory demands by enabling people to experience negative emotions in a mindful and non-judgmental manner (Jazaieri et al. 2014; Leary et al. 2007; Neff et al. 2007) and be open towards failures (Blackie and Kocovski 2018; Neff et al. 2005; Petersen 2014). As a result, self-compassionate people may find a difficult self-control task more manageable than less self-compassionate people.

This experience sampling study aims to elucidate the mechanisms through which trait self-compassion influences daily life self-control. One potential mechanism is that trait self-compassion protects self-efficacy when handling difficult tasks. We hypothesized that trait self-compassion moderates the effect of perceived difficulty on self-efficacy, which in turn, influences everyday self-control performance. Specifically, for less self-compassionate people, perceived difficulty of a self-control task should decrease self-efficacy and, subsequently, impair self-control performance. In contrast, for more self-compassionate people, the perceived difficulty of a self-control task should not decrease self-efficacy and self-control performance. As the experience sampling method provides a valid measure of people’s momentary experience in real life (Scollon et al. 2009), we could closely examine how trait self-compassion affects daily self-control.

Method

Participants

One hundred and twenty-five college students were recruited in a university in Hong Kong for a 10-week intervention study on social media use. The study involved three phases of experience sampling, one before the intervention, and two after. No specific instructions about the intervention were given in the first experience sampling phase. Our analyses were based on the data collected in this phase.

In the 7-day experience sampling reported in this paper, participants received 10 HKD for each responded survey. They received another 100 HKD for responding to more than 90% of surveys. Ten participants withdrew from the study after the initial orientation. Eventually, we retained data from 115 participants (81 females and 34 males; Mage = 20.52; SDage = 1.60).

Procedure

An initial orientation was conducted 1 week before the experience sampling phase. After informed consent was obtained, a trained research assistant administered the personality survey and instructed participants to respond to the experience sampling survey. In the orientation, the research assistant also explained to participants that a self-control behavior entails acting with one’s abstract, long-term motive instead of acting with one’s concrete, proximal motives. Several self-control examples (e.g., resisting the desire to drink alcohol, persisting on writing up a term paper) were given to clarify the meanings of self-control. One week after the orientation session, participants participated in a 7-day experience sampling survey in which they received five signals per day via the SurveySignal platform (Hofmann and Patel 2015). Signals were sent to participants at a random time every 3 h starting from 10 a.m. A survey link that was created by Qualtrics was embedded in each experience sampling signal. Two adjacent signals were separated by at least 30 min. Participants needed to respond to the survey within 30 min before the link expired.

Measures

Trait Self-Compassion

The self-compassion scale (short form, Raes et al. 2011) was used to assess individual differences in trait self-compassion. This scale has 12 items (e.g., “I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like”). This scale was commonly used to measure trait-level self-compassion in the literature (e.g., Marshall et al. 2015; Muris and Petrocchi 2017). Participants responded to these items on a 5-point scale (from 1 = never to 5 = always). The reliability of the scale in the present study was satisfactory (α = .77).

Trait Self-Control

Trait self-control was included as a control variable. It was measured by the trait self-control scale developed by Tangney et al. (2004). This scale has 13 items (e.g., “I am good at resisting temptation”), and it is one of the most commonly used trait self-control scales in the literature (for a meta-analytic review, see De Ridder et al. (2018)). Participants responded to these items on a 5-point scale (from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree). The reliability of the scale in the present study was satisfactory (α = .77).

Experience Sampling Survey

In each experience sampling survey, participants were first asked, “In the past 30 minutes, have you exerted self-control?”. They were allowed to choose between three options: (1) “yes, resisting a desire (When you have a desire, you want to fulfill or enjoy something immediately),” (2) “yes, persisting on a task,” and (3) “no.” If they chose option 3 (i.e., no self-control conflict), they would then be directed to a survey about their surrounding environment. If they chose option 1, they were asked to name the desire they were resisting. If they chose option 2, they were asked to name the goal they were persisting on.

Participants who chose option 1 and 2 then answered a set of additional questions regarding their self-control experiences (see Supplementary Materials for a full list of questions). Central to our research questions, we measured perceived difficulty of self-control (“How hard was it to completely focus on resisting [nominated desire]/persisting on [nominated goal]?”), self-efficacy (“How confident were you that you would succeed in resisting [nominated desire]/persisting on [nominated goal]?”), and self-control success (“Were you successful at resisting [nominated desire]/persisting on [nominated goal]?”). Participants responded to these questions on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 7 = extremely).

Data Analyses

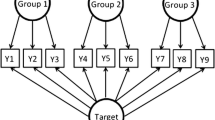

The present data contained a hierarchical structure in which episodes of self-control conflicts were nested within individuals (1725 episodes of self-control conflicts nested within 115 participants). Multilevel structural equation models (MSEM) with random slopes and intercepts were employed to account for the hierarchical structure of the collected data. According to Preacher et al. (2010), MSEM has several advantages in estimating moderation and mediation in nested data. First, MSEM reduces sampling error by treating all group standings on level 1 variable as latent. Second, the latent variables also help to account for measurement error. Third, and more importantly, MSEM decomposes the between-individual and within-individual components of all variables to estimate the direct and indirect effects at each level. Mplus version 8.0 was used to analyze the data. The Mplus code of our analysis can be found in the supplementary materials.

In the present investigations, we were primarily interested in the cross-level interaction between trait self-compassion and perceived difficulty in predicting self-efficacy. We proposed a multilevel moderated mediation model such that self-compassion × difficulty interaction could influence self-control success via self-efficacy. We used Preacher et al. (2016)’s framework to test the multilevel conditional indirect effects. This approach allows estimation of covariances for level 1 random effects, mediation effect, and the various paths that are components of these mediation effects without conflating the level 1 and level 2 associations. In all multilevel analysis, trait self-control was used as a covariate to ensure that the effects of trait self-compassion were not confounded by trait self-control. We quantified the conditional indirect effect by the product of the moderation effect in the first-stage mediation process and the main effect in the second-stage mediation process. Listwise deletion was used to handle missing data in the present analysis. In other words, the entire data point was excluded from analysis if any single variable was missing.

Results

Non-response Patterns and Correlations

The total response rate was 84.1%. On average, participants completed 29.1 experience sampling surveys. Among these responses, 12.19% (409 episodes) of responses indicated the resistance of a desire, 39.23% (1316 episodes) indicated the persistence of an event, and 48.57% (1629 episodes) indicated no self-control conflicts. Correlation analysis was conducted to check whether trait level variables affected the number of responses. Both trait self-compassion (r = − .17, p = .07) and trait self-control (r = −.09, p = .38) did not significantly correlate with the non-response rate. The frequency of self-control conflicts reported by participants can be found in Fig. 1.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics, the between-individual and the within-individual correlation of variables. It is worth noting that trait self-compassion was not related to perceived difficulty, self-efficacy, and success at the between-individual level.

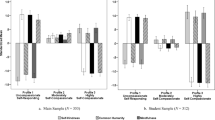

The Moderation Effect of Trait Self-Compassion on the Relationship Between Perceived Difficulty and Self-Efficacy

First, perceived difficulty negatively predicted self-efficacy, B = − 0.14, SE = 0.05, p = .002, 95% CI [− 0.23, − 0.05]. Trait self-compassion did not predict self-efficacy, B = − 0.04 SE = 0.16, p = .79, 95% CI [− 0.36, 0.28]. As predicted, trait self-compassion interacted with perceived difficulty, B = 0.17, SE = 0.08, p = .03, 95% CI [0.02, 0.32] in predicting self-efficacy. Simple-slope analyses showed that the negative effect of perceived difficulty on self-efficacy was found among participants with low self-compassion (1 SD below mean), B = − 0.23, SE = 0.06, p < .001, 95% CI [− 0.34, − 0.12], but not among those with high self-compassion (1 SD above mean), B = − 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = .53, 95% CI [− 0.17, 0.09]. Table 2 presents the path coefficients of this model.

How Does Trait Self-Compassion Relate to Self-Control Success?

Perception of difficulty may generally undermine self-efficacy and subsequently impair self-control. Nevertheless, as our analyses suggested that trait self-compassion could buffer the detrimental effects of perceived difficulty on self-efficacy, trait self-compassion might also reduce the detrimental effects of perceived difficulty on self-control successes via preserving self-efficacy. Therefore, we tested the moderated mediation in our full model. Again, trait self-control was used as a covariate in the model.

As predicted, trait self-compassion moderated the effect of perceived difficulty on self-efficacy, B = 0.20, SE = 0.08, p = .02, 95% CI [0.03, 0.31], which in turn, predicted self-control success, B = 0.53, SE = 0.05, p < .001, 95% CI [0.44, 0.62]. For those who were low in self-compassion, the mediation effect was significant such that perceived difficulty reduced self-control successes via reducing self-efficacy, B = − 0.15, SE = 0.04, p < .001, 95% CI [− 0.20, − 0.07]. However, for those who were high in trait self-compassion (1SD above mean), the mediation was non-significant, B = − 0.04, SE = 0.04, p = .37, 95% CI [− 0.11, 0.04]. Figure 2 presents the path coefficients of this multilevel moderated mediation model.

Discussion

Although trait self-compassion is commonly found to facilitate self-control, past research exclusively focused on health-related behaviors. While this study sampled everyday self-control behaviors that were not limited to the health domain, we observed that trait self-compassion did not relate to the average levels of perceived difficulty, self-efficacy, and success of self-control.

The current study provides a more nuanced view regarding the relationship between trait self-compassion and everyday self-control. In particular, we observed that trait self-compassion moderated the impact of perceived task difficulty on self-efficacy. When people evaluate their efficacy to sustain self-control, they may take into account information such as mastery experience, feedback from others, emotional and physiological states (Usher and Pajares 2006). While perceived difficulty generally undermined self-efficacy and subsequently self-control performance, trait self-compassion appeared to mitigate the negative impact of perceived difficulty on self-efficacy. There are two possible reasons. First, self-compassion inspires self-soothing thoughts. Second, self-compassion reduces demands for emotion regulation by enabling individuals to accept and reappraise aversive experiences, including frustration, fear, and failure, in a different light.

Although self-control has long been recognized as a pivotal factor in human well-being, people usually find it very difficult to sustain (Shimai et al. 2006). While failure to sustain self-control may be considered immoral (Baumeister and Exline 1999; Mooijman et al. 2018), individuals may feel both strong needs for self-control and anxious about potential failures. Such desires for self-control can ironically reduce self-efficacy and undermine self-control effort (Uziel and Baumeister 2017). One may wonder if strategic self-indulgence with desires as a reward for hard work would enhance long-term self-control performance and well-being. It is interesting to examine whether self-compassionate people may strategically use self-indulgence as a means to cope with self-control demands.

Many interventions have been devised to improve self-control (Friese et al. 2017). Self-control training typically requires people to repeatedly inhibit a dominant response for an extended period (e.g., not using dominant hands for 2 weeks). These tasks are usually perceived as difficult and unlikely to succeed (Hagger et al. 2010). In light of the present findings, inhibition training may not benefit individuals low in self-compassion, as they are more likely to feel inefficacious while completing the training. Future research could investigate whether self-compassion moderates the effects of these inhibition training. Also, it may be a worthy endeavor to study the incremental benefits of self-compassion induction in the traditional self-control training program.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present research tested a multilevel moderated mediation model to explain when and how trait self-compassion facilitates momentary self-control in everyday life. Although the experience sampling method allows more accurate assessments of daily experiences that are less prone to memory bias (Scollon et al. 2009), this study could not eliminate the inherent limitations associated with self-reports. For example, self-enhancement bias may motivate participants to perceive their self-control behaviors as more successful. Therefore, future research should also examine whether trait self-compassion relates to performance in standard self-control tasks (e.g., Stroop task). Due to the correlational nature of the data, the present research could not establish the causal relationship between efficacy belief and perceived difficulty. In the future, researchers could experimentally manipulate task difficulty to evaluate the causal sequences further.

The present study suggested that self-efficacy is an underlying process through which trait self-compassion benefits everyday self-control. Trait self-compassion may also influence self-control through other mechanisms. For instance, self-compassionate individuals are more likely to use adaptive emotional regulation strategies to manage aversive feelings (e.g., Finlay-Jones et al. 2015). Future research may illuminate further the various processes underlying the effect of trait self-compassion on self-control.

Finally, the present study only considered the trait level of self-compassion. In reality, the state level of self-compassion could change momentarily. Future studies could measure or manipulate state self-compassion to study how state self-compassion can contribute to self-control success.

Data Availability

The data analyzed in the current study are available at the Open Science Framework (http://osf.io/dp8e6/).

References

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.37.2.122.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Macmillan.

Baumeister, R. F., & Exline, J. J. (1999). Virtue, personality, and social relations: self-control as the moral muscle. Journal of Personality, 67(6), 1165–1194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00086.

Baumeister, R. F., & Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation, ego depletion, and motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 1(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00001.x.

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x.

Biber, D. D., & Ellis, R. (2019). The effect of self-compassion on the self-regulation of health behaviors: a systematic review. Journal of Health Psychology, 24(4), 2060–2071. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317713361.

Blackie, R. A., & Kocovski, N. L. (2018). Examining the relationships among self-compassion, social anxiety, and post-event processing. Psychological Reports, 121(4), 669–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117740138.

Blanden, G., Butts, C., Reid, M., & Keen, L. (2018). Self-reported lifetime violence exposure and self-compassion associated with satisfaction of life in historically Black college and university students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518791596.

Bluth, K., & Neff, K. D. (2018). New frontiers in understanding the benefits of self-compassion. Self and Identity, 17(6), 605–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1508494.

Brion, J. M., Leary, M. R., & Drabkin, A. S. (2014). Self-compassion and reactions to serious illness: the case of HIV. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(2), 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312467391.

Ceccarelli, L., Giuliano, R. J., Glazebrook, C., & Strachan, S. (2019). Self-compassion and psycho-physiological recovery from recalled sport failure. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1564. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105312467391.

Chow, J. T., Hui, C. M., & Lau, S. (2015). A depleted mind feels inefficacious: ego-depletion reduces self-efficacy to exert further self-control. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(6), 754–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2120.

Daly, M., Delaney, L., Egan, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2015). Childhood self-control and unemployment throughout the life span: evidence from two British cohort studies. Psychological Science, 26(6), 709–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615569001.

De Ridder, D. T., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., Finkenauer, C., Stok, F. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2018). Taking stock of self-control: a meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. In R. F. Baumeister (Ed.), Self-Regulation and self-control (pp. 221–274). Abingdon: Routledge.

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. (2017). The science and practice of self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(5), 715–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617690880.

Ferrari, M., Hunt, C., Harrysunker, A., Abbott, M. J., Beath, A. P., & Einstein, D. A. (2019). Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: a meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6.

Finlay-Jones, A. L., Rees, C. S., & Kane, R. T. (2015). Self-compassion, emotion regulation and stress among Australian psychologists: testing an emotion regulation model of self-compassion using structural equation modeling. PLoS One, 10(7), e0133481. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133481.

Friese, M., Frankenbach, J., Job, V., & Loschelder, D. D. (2017). Does self-control training improve self-control? A meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 1077–1099. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617697076.

Fujita, K. (2011). On conceptualizing self-control as more than the effortful inhibition of impulses. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(4), 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311411165.

Gilbert, P. (2005). Compassion and cruelty: a biopsychosocial approach. In Gilbert (Ed.), Compassion: Conceptualisations, research, and use in psychotherapy (pp. 9–74). Abingdon: Routledge.

Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind. London: Consa Robinson.

Hagger, M. S., Wood, C., Stiff, C., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 495–525. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019486.

Hallion, M., Taylor, A., Roberts, R., & Ashe, M. (2019). Exploring the association between physical activity participation and self-compassion in middle-aged adults. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 8(3), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1037/spy0000150.

Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1994). Losing control: how and why people fail at self-regulation. San Diego: Academic.

Hofmann, W., & Patel, P. V. (2015). SurveySignal: a convenient solution for experience sampling research using participants’ own smartphones. Social Science Computer Review, 33(2), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314525117.

Homan, K. J., & Sirois, F. M. (2017). Self-compassion and physical health: exploring the roles of perceived stress and health-promoting behaviors. Health Psychology Open, 4(2), 2055102917729542. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102917729542.

Inzlicht, M., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2012). What is ego depletion? Toward a mechanistic revision of the resource model of self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(5), 450–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612454134.

Jazaieri, H., McGonigal, K., Jinpa, T., Doty, J. R., Gross, J. J., & Goldin, P. R. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of compassion cultivation training: effects on mindfulness, affect, and emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion, 38(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9368-z.

Kelly, A. C., Zuroff, D. C., Foa, C. L., & Gilbert, P. (2010). Who benefits from training in self-compassionate self-regulation? A study of smoking reduction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(7), 727–755. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.7.727.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: the implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887.

Mantzios, M., Wilson, J. C., Linnell, M., & Morris, P. (2015). The role of negative cognition, intolerance of uncertainty, mindfulness, and self-compassion in weight regulation among male army recruits. Mindfulness, 6(3), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-014-0286-2.

Marshall, S. L., Parker, P. D., Ciarrochi, J., Sahdra, B., Jackson, C. J., & Heaven, P. C. (2015). Self-compassion protects against the negative effects of low self-esteem: a longitudinal study in a large adolescent sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 116–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.049.

Molden, D. C., Hui, C. M., & Scholer, A. A. (2016). Understanding self-regulation failure: a motivated effort-allocation account. In E. R. Hirt, J. J. Clarkson, & L. Jia (Eds.), Self-regulation and ego control (pp. 425–459). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Mooijman, M., Meindl, P., Oyserman, D., Monterosso, J., Dehghani, M., Doris, J. M., & Graham, J. (2018). Resisting temptation for the good of the group: binding moral values and the moralization of self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(3), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000149.

Muris, P., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 24(2), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2005.

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032.

Neff, K. D., Hsieh, Y. P., & Dejitterat, K. (2005). Self-compassion, achievement goals, and coping with academic failure. Self and Identity, 4(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500444000317.

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. L. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 908–916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.08.002.

Petersen, L. E. (2014). Self-compassion and self-protection strategies: the impact of self-compassion on the use of self-handicapping and sandbagging. Personality and Individual Differences, 56, 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.036.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141.

Preacher, K. J., Zhang, Z., & Zyphur, M. J. (2016). Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000052.

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702.

Saunders, B., Milyavskaya, M., & Inzlicht, M. (2015). Variation in cognitive control as emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702.

Scollon, C. N., Prieto, C. K., & Diener, E. (2009). Experience sampling: promises and pitfalls, strength and weaknesses. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023605205115.

Semenchuk, B. N., Strachan, S. M., & Fortier, M. (2018). Self-compassion and the self-regulation of exercise: reactions to recalled exercise setbacks. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 40(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2017-0242.

Shimai, S., Otake, K., Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2006). Convergence of character strengths in American and Japanese young adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(3), 311–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-3647-7.

Sirois, F. M., Nauts, S., & Molnar, D. S. (2019). Self-compassion and bedtime procrastination: an emotion regulation perspective. Mindfulness, 10(3), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0983-3.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00263.x.

Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2006). Sources of academic and self-regulatory efficacy beliefs of entering middle school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 31(2), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.03.002.

Uziel, L., & Baumeister, R. F. (2017). The self-control irony: desire for self-control limits exertion of self-control in demanding settings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(5), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217695555.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Faculty Development Scheme of the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (project no. UGC/FDS15/H03/16).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TC designed and executed the study, performed the data analysis, and wrote the paper. CH collaborated in the design of the study and the editing of the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Board of the Hong Kong Shue Yan University.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chow, T.S., Hui, C.M. How Does Trait Self-Compassion Benefit Self-Control in Daily Life? An Experience Sampling Study. Mindfulness 12, 162–169 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01509-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01509-0