Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this meta-analytic review was to determine the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students as well as to explore potential moderators that predict the magnitude of MBIs’ effects.

Methods

Twenty-five randomized controlled trials were identified eligible for inclusion of the current meta-analytic review. Pooled effect sizes were calculated using random-effects models by summarizing the differences of pre-post changes in depressive symptoms between the intervention and control conditions. Effect sizes of universal, selective, and indicated MBIs were assessed. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were used to explore potential moderators of the intervention effects.

Results

MBIs were found effective for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students. The overall mean effect size was 0.52, which was considered moderate. Universal, selective, and indicated MBIs were all associated with significant reductions in depressive symptoms, with effect sizes of 0.41, 0.44, and 0.88. Larger effects emerged for participants from indicated MBIs, studies with small sample sizes, MBIs with medium length, and MBIs delivered on a weekly basis.

Conclusions

This meta-analytic review reinforces the evidence to support the use of MBIs for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students. In particular, our analyses suggest a range of moderators associated with MBIs’ effects. Further studies with methodological rigor are needed to confirm and extend the findings of this meta-analytic review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide (Murray and Lopez 1997). University students are characterized as experiencing the critical transition period from adolescence to adulthood that is highly associated with the initial onset of depression (Dyson and Renk 2006; Reyes-Rodriguez et al. 2013). The prevalence of depression among university students is evidenced to range from 10 to 85% with a weighted mean prevalence of 30.6% (Ibrahim et al. 2013a) more than twofold higher than that in the general population (Moussavi et al. 2007). Evidence suggests that students with depression are associated with worse relationships with others, decreased engagement in campus activities, poorer performance on grade average, and lower rates of normal graduation (Hysenbegasi et al. 2005; Keyes et al. 2012; Salzer 2012). In addition, depression can place university students at severe conditions through greater risk of acute infectious illness, smoking, alcohol use, and self-injurious behaviors which in extreme cases may lead to suicidal ideation and death (Adams et al. 2008; Farabaugh et al. 2012; Kenney and Holahan 2008; Weitzman 2004). Elevated but sub-clinical levels of depressive symptoms, which have been associated with considerable impairment and increased risk for clinical depression, are also common in university students (Gress-Smith et al. 2015; Rotenstein et al. 2016; Wells et al. 1987). However, few students experiencing depressive symptoms receive any treatment and relapses of depressive symptoms frequently occur, underscoring the importance of effective interventions that could be initiated earlier and reach larger groups to prevent depressive symptoms in university students (Eisenberg and Chung 2012; Garlow et al. 2008)

Derived from ancient Buddhist and Yoga practices, mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in university populations have demonstrated a wide array of benefits on stress reduction, psychological wellbeing, interpersonal relationships, and health-related behaviors (Astin 1997; Cohen and Miller 2009; Dvorakova et al. 2017; Shapiro et al. 2008). Mindfulness commonly refers to a state of being attentive to and aware of what is taking place in the present, including one's sensations, thoughts, bodily states, consciousness, and the environment, while encouraging openness, curiosity, and acceptance (Bishop et al. 2010; Brown and Ryan 2003). The basic premise underlying MBIs is that experiencing the present moment non-judgmentally and openly can counter the impacts of stressors effectively, as excessive orientation towards the past or future when dealing with stressors can be associated with feelings of depression (Kabat-Zinn 2003). The most commonly available and evaluated MBIs are mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) programs. MBSR is a structured, manualized program initially developed for the management of chronic pain and is now widely used to reduce psychological morbidity related to chronic illness (Bishop et al. 2004). MBCT, derived from MBSR and integrated with elements from cognitive therapy, was originally designed for relapse prevention in recurrent depression and has been extended in recent years to individuals at risk of depressive and anxiety disorders (Segal et al. 2002). The standard practice for both programs is a group-based intervention held over 8–10 weeks, with weekly two-hour sessions, inclusion of daily homework, and a one-day retreat (Abbott et al. 2014).

With growing popularity, a number of meta-analyses have been conducted to aggregate data of randomized controlled trials that examined the efficacy of MBIs for depressive symptoms. An overview of 23 systematic reviews and meta-analyses covering 115 unique trials and 8683 unique individuals with various conditions found a small but significant effect size of 0.37 for MBIs using the standardized MBSR or MBCT programs (Gotink et al. 2015). Small to moderate effect sizes (e.g., values between 0.2 and 0.8), were reported for a range of other MBIs, including online MBIs, self-help MBIs, and stand-alone mindfulness exercises (Blanck et al. 2018; Cavanagh et al. 2014; Spijkerman et al. 2016). In addition, a wider range of effect sizes were exhibited for a broad range of populations. For instance, a moderate effect size of 0.64 was indicated for adults who were overweight or obese (Rogers et al. 2017), a small effect size of 0.35 was shown for people with vascular disease (Abbott et al. 2014), while effect sizes were negligible for women during pregnancy or the perinatal period (Dhillon et al. 2017; Taylor et al. 2016). However, despite the burgeoning literature of various MBIs in university students, no prior reviews have applied the meta-analytic method to quantify the effect size. A meta-analytic review would help determine whether MBIs could really benefit university students as intended if delivered on a larger scale.

Even within the scope of university students, the efficacy of MBIs may still vary for different population groups. Depression prevention programs can be classified into universal, selective, and indicated approaches, depending on different population groups (Mrazek and Haggerty 1994). Universal approaches are targeted to all members of a given population that have not been identified on the basis of individual risk; selective approaches are targeted to individuals whose risk of developing depression are significantly higher than average; and indicated approaches are targeted to individuals who evidence early signs of depression without meeting diagnostic levels. Although a number of MBIs have been developed with different approaches to target depressive symptoms among university students, it remains unclear whether universal, selective, and indicated MBIs are effective respectively.

Furthermore, there has been a poor understanding of the mechanism underpinning the relationship between potential moderators and the effects of MBIs for university students. Such information could help increase the yield of future MBIs by identifying specific features associated with stronger effects. As such, a range of putative moderators relevant to participant demographics and intervention conditions were assessed in this meta-analytic review. Given that high-risk individuals would be more motivated to engage in prevention content (Stice et al. 2009), larger and more robust effects may emerge for selective and indicated MBIs as compared with universal ones. Likewise, we expected MBIs would produce stronger effects for female students, medical students, as well as first-year students based on the evidence that greater levels of depressive symptoms and higher prevalences of depression are often exhibited for these population groups (Puthran et al. 2016). As individualized interventions would better address participants’ various needs, MBIs administered individually may be more effective than those administered in a group format. Given that increased opportunities to acquire and apply intervention skills would theoretically produce larger effects, MBIs with assignment of self-practice (e.g., homework) may result in greater reductions in depressive symptoms. Similarly, we expected that longer interventions and greater frequency would be associated with stronger effects. Furthermore, it is possible that variation in program content (e.g., MBCT and MBSR) would result in different intervention effects. In addition, we examined three other variables that could influence the intervention effects: sample size, study quality, and attrition rate. Examination of these variables would help determine whether findings based on current evidence were biased by studies with small sample sizes, suboptimal study quality, and high attrition rates.

Given an increasingly larger scale of MBIs targeting depressive symptoms among university students, in the presence of insufficient understanding, more robust evidence is needed to minimize the risk of overtranslation. A meta-analytic review could help determine whether MBIs should be proposed as a real candidate for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students. Furthermore, it would help distinguish the most successful MBIs from those with invalid or small effect sizes. Finally, it may help identify the mechanism in which MBIs could be most effective. Therefore, with a meta-analytic review, the primary purpose of this study was to determine whether MBIs are effective for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students. We hypothesized that students who participated in MBIs would report lower levels of depressive symptoms. In particular, we examined the efficacy of universal, selective, and indicated MBIs respectively. The secondary purpose was to explore factors that could predict magnitude of the intervention effects.

Methods

This study was conducted in adherence to the PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions (Moher et al. 2009). See the PRISMA Checklist for details (Supplementary Materials).

Search Strategy and Data Source

Studies that assessed the efficacy of MBIs aimed at preventing depressive symptoms for university students were identified through online searches. Five electronic databases Medline, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central were searched from their inception through 1 November 2017, and updated up to 13 November 2018. The online search strategy combined the following terms: (mindful or mindfulness or meditation) and (depression or depressive or depressed) and (“university students” or “college students” or “undergraduate students” or “graduate students” or “medical students” or “nursing students”). Reference lists from relevant reviews and retrieved studies were reviewed and searched to identify additional records.

Eligibility Criteria for Inclusion

Studies were eligible for inclusion in this meta-analytic review if (1) the study was targeted to university students; (2) the study assessed a mindfulness-based intervention, including MBSR, MBCT, and other practices that incorporated the use of mindfulness such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999); (3) the study compared a mindfulness-based intervention condition with an inactive control condition (e.g., no intervention, waiting list, assessment-only, and usual care); (4) the study evaluated depressive symptoms as a major outcome through validated measures; and (5) the study was designed as a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Study Selection Procedure

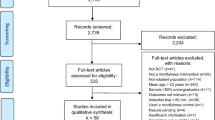

Initial records identified from electronic database searching, relevant reviews, and retrieved studies were imported into Endnote X7. After removal of duplicates, titles, and abstracts were screened to identify potentially relevant studies. The screening process was conducted by two reviewers (LM and YZ) independently. Studies that yielded disagreements between the two reviewers were included for further evaluation. Full-text articles of the potentially relevant studies were retrieved for detailed review. Each study was then evaluated by the first (LM) and second reviewer (YZ) independently to determine eligibility. This yielded a kappa (κ) coefficient of 0.76, indicating there was good inter-rater agreement between the two reviewers. Following their independent assessments, disagreements were resolved through discussion. If disagreements persisted, the third reviewer (ZC) was consulted. In case of multiple publications with partially or completely overlapped samples, we selected the study for inclusion following the sequence of data sufficiency, sample size, and publication date.

Data Extraction

An abstraction form was piloted and used to extract data from the included studies. Two categories of characteristics relevant to the participants and interventions were coded in this study. Characteristics of participants included sample size, mean age, the proportion of female students, participant risk status (universal vs. selective vs. indicated), whether the participants were first-year students, and whether the participants were medical students (including nursing students). In this meta-analytic review, trials were categorized as universal if all students were eligible for inclusion, selective if the participants were included on the basis of endorsing greater risk of depression than the general students (e.g., first-year students and medical students), and indicated if the participants reported elevated depressive symptoms or other forms of psychological distress (early interventions were also included and categorized as indicated ones). Characteristics of interventions included length of intervention, format of administration (group vs. individual), type of MBI (MBSR vs. MBCT vs. ACT vs. others), frequency of delivery, rate of attrition, and whether the intervention included self-practice assignments. Table 1 presents a summary of characteristics coded for each of the studies included in the current meta-analytic review. For each included study, data were extracted by the first reviewer (LM) and then fully checked by the second reviewer (YZ). For any disagreements, the two reviewers discussed and reached a consensus, and if necessary, the third reviewer (ZC) was consulted.

Risk of Bias Assessment

Following the recommendation of the Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool (Higgins et al. 2011), four domains with potential risk of bias were assessed for each individual study: selection bias (whether the random sequence was generated), allocation bias (whether the allocation process was concealed), detection bias (whether the outcome was assessed by blinded assessors), and attrition bias (whether the incomplete outcome data were handled). As it is rarely possible for participants to be blinded to the experimental conditions because of the nature of interventions, we left out the assessment of performance bias (whether participants were blinded to intervention or control conditions). In particular, studies that reported the use of intent-to-treat analysis were categorized as low risk of attrition bias. As a result, studies that showed high risk of bias within 1 domain or less were considered as high quality, otherwise considered as low quality. Two reviewers (LM and YZ) conducted the assessments independently and we calculated the inter-rater agreement between the two reviewers using kappa (κ) coefficients. Following the two reviewers’ independent assessments, discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Intervention effects were defined as the difference in pre-post changes of mean scores in depressive symptoms between intervention and control conditions. To evaluate the effect sizes, standardized mean differences (SMD), and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Because a number of studies had small sample sizes, we calculated the effect sizes using Hedges’ g which corrects small sample bias (Hedges and Olkin 1985). For each study, effect size (Hedges’ g or SMD) was calculated via dividing the difference in the mean change score between intervention and control conditions by the pooled standard deviation at post-intervention, corrected for small sample bias: \( g=\left(\frac{M_{I,\mathrm{Change}}-{M}_{C,\mathrm{Change}}}{{\mathrm{SD}}_{\mathrm{P}}}\right)\times C \), where the pooled standard deviation was defined as \( {\mathrm{SD}}_{\mathrm{P}}=\sqrt{\frac{\left({N}_I-1\right)\times {\mathrm{SD}}_I^2+\left({N}_C-1\right)\times {\mathrm{SD}}_C^2}{N_I+{N}_C-2}} \) and the correction factor was defined as \( C=1-\frac{3}{4\times \left({N}_I+{N}_C-2\right)-1} \). Positive effect sizes represented greater reductions in depressive symptoms for intervention conditions as compared to control conditions. Effect sizes of 0.8 or higher were interpreted as large, while effect sizes of 0.5–0.7 were regarded as moderate and effect sizes lower than 0.5 were considered small (Cohen 1988). To evaluate the pooled effect sizes, random-effects models and inverse variance weighted methods were used, as the assumption of fixed-effects models was likely to be violated because of the non-negligible heterogeneity across the studies (Dersimonian and Laird 1986).

Heterogeneity was assessed through I2 statistic that was distinguished as low, moderate, substantial, and considerable with values of 0%~40%, 30%~60%, 50%~90%, and 75%~100% (Deeks et al. 2011). Influence analyses were conducted to evaluate the impact of each individual study on the pooled effect sizes. In the influence analyses, pooled effect sizes were recalculated on exclusion of each individual study one by one. Exploratory analyses using subgroup and meta-regression analyses were undertaken to assess potential moderators of effect sizes (Thompson and Sharp 1999). Subgroup analyses were conducted on categorical characteristics and meta-regression analyses were performed on continuous characteristics. Publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plot, which indicates publication bias if an asymmetric distribution is produced. In case of any publication bias, we applied the trim-and-fill method to yield an adjusted effect size accounting for missing studies that lead to publication bias (Duval and Tweedie 2000). All the analyses were performed with Stata release 12 (StataCorp) and p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Summary of Study Selection

A PRISMA flowchart summarizing the process for inclusion of studies is presented in Figure 1. A total of 768 records were initially identified from database searching and reference review. After removal of duplicates, 546 studies were screened for titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant studies. As a result, 109 full-text studies were retrieved for detailed review. Of these studies, 84 were further excluded for the following reasons: 13 because the study was not targeting university students; 19 because the study did not include an intervention of MBIs; 9 because the study did not include a relevant control condition; 17 because the study did not report outcome on depressive symptoms; 19 because the study was not an RCT; 4 because of multiple publications with overlapped samples; and 3 because the study was not written in English. Thus in total, 25 RCTs were eligible for inclusion in the present meta-analytic review. Table 2 lists the included studies, describes the samples, characterizes the interventions, and summarizes the main findings.

Participant Demographics

In total, the studies included 2472 participants with sample sizes ranging from 41 to 298. The mean age of participants ranged from 18 to 32 with an average of 22.7 years. The average proportion of female students was 74.6%. Of the 25 studies, three were targeted to first-year students and six were targeted to medical students. As one study was targeted to first-year medical students, eight studies were categorized as the selective approach. Eleven studies were targeted to general students and were categorized as the universal approach. In addition, six studies were targeted to students experiencing elevated depressive symptoms or other forms of psychological distress and were categorized as the indicated approach.

Intervention Conditions

Overall, the length of intervention ranged from 1 week to 24 weeks with an average of 7 weeks. The majority of interventions were administered in a group format (n = 15), 9 were administered individually, and 1 was administered both individually and in a group format (both group and individual sessions were used). Over half of the interventions were delivered on a weekly basis (n = 14). The rate of attrition ranged from 0 to 57% with an average of 21%. The majority of interventions included self-practice assignments (n = 21). In addition to MBSR (n = 7), MBCT (n = 4) and ACT (n = 4), a range of mindfulness practices (e.g., breath meditation, body awareness, reflective listening, walking meditation, self-compassion course, and loving-kindness meditation) were used in other studies.

Qualitative Synthesis of Major Study Findings

Over two-thirds of the trials (76%) found significant reductions in depressive symptoms at post-intervention for mindfulness conditions relative to control conditions. Of the 25 trials, only eight conducted follow-up assessments, allowing for temporal analyses. Of these, three trials reported assessments at one-month follow-up, indicating strong evidence that the gains were largely maintained at follow-up. Three trials reported assessments at 2- to 3-month follow-up, finding little evidence in favor of the mindfulness conditions. In addition, two trials reported assessments at longer follow-ups. One of them showed evidence of an effect at 6-month follow-up and the other found evidence in support of the mindfulness condition at 12-month follow-up.

Risk of Bias Assessment

The results of risk of bias assessment are presented in Table 3. The kappa (κ) coefficients for each domain of potential risk of bias and overall study quality rating ranged from 0.78 to 1.00, underscoring high inter-rater agreement between the two reviewers. Eighteen trials (72%) described the random sequence generation process such as the use of a computer random number generator. Five trials (20%) stated that the allocation process was concealed. Six trials (24%) stated blinding of assessors for the outcome measurements. Ten trials (40%) reported the use of intent-to-treat analysis to handle the incomplete outcome data. As a result, five trials (20%) showed high risk of bias within 1 domain or less and were categorized as high quality.

Quantitative Synthesis of Overall Effect Sizes

Data from 22 trials were eligible for inclusion of the meta-analysis. As one trial assessed two different MBIs compared with the same control condition (Delgado-Pastor et al., 2015), these trials in total resulted in 23 comparisons. A summary of all effect sizes under corresponding measures is presented in Table 1. Effect sizes of these comparisons ranged from 0.13 to 1.31. No comparisons produced negative effect sizes. The mean effect size was 0.52 (95%CI 0.39, 0.65), which was considered moderate. The heterogeneity across these studies was low to moderate (I2 = 39.3%). The funnel plot had some asymmetry, which suggested indications of publication bias. After adjusting for possible publication bias with the trim-and-fill method, seven hypothetical studies were incorporated into the meta-analysis and the mean effect size dropped to 0.38 (95%CI 0.24, 0.53). In the influence analyses, there was no substantial change over the effect sizes, which ranged from 0.45 (95%CI 0.36, 0.55) to 0.52 (95%CI 0.42, 0.63) on exclusion of each study. In addition, as two mindfulness conditions were compared with the same control condition in one trial, these comparisons were not independent of each other and findings of the meta-analysis may be biased. Therefore, we conducted additional meta-analyses in which only one comparison of this study was included. The overall effect sizes remained around 0.52 after exclusion of either comparison.

Effect Sizes of Universal, Selective, and Indicated MBIs

Meta-analysis results of universal, selective, and indicated MBIs are presented in Figure 2. Data from ten comparisons contributed to the meta-analysis of universal MBIs, which produced an effect size of 0.41 (95%CI 0.28, 0.55). There were few indications of heterogeneity across universal MBIs (I2 = 2.3%). Six comparisons were categorized as selective MBIs, which resulted in an effect size of 0.44 (95%CI 0.18, 0.70). The heterogeneity across these MBIs was moderate (I2 = 48.8%). Seven comparisons were categorized as indicated MBIs and pooled effect size of these comparisons was 0.88 (95%CI 0.64, 1.11). Heterogeneity was zero across indicated MBIs.

Associations Between Putative Moderators and Intervention Effects

Results of moderator analyses are presented in Table 4. Categorical and continuous moderators were assessed separately. We found that participant risk status was significantly associated with the effect size (p = 0.04); indicated MBIs produced stronger effects as compared with universal MBIs (p = 0.03), while there were few indications for selective MBIs to be different from either indicated or universal MBIs (p > 0.05). There was a trend for greater proportion of female students to be associated with larger reductions in depressive symptoms (slope = 0.007, p = 0.10). There were few indications for the effect size to be associated with other participant demographics, including age of participants, whether the participants were first-year students, and whether the participants were medical students (p > 0.05). We did not find that length of intervention was significantly associated with the effect size for the whole studies (slope = − 0.005, p = 0.68). Because the length of intervention varied in a wide range with a few atypical lengths and there was evidence that interventions with medium length could be more successful in reducing depressive symptoms (Calear and Helen 2010), we further explored the association between length of intervention and the effect size in two ways. We first conducted a meta-regression analysis in which interventions longer than the average (> 7 weeks) were excluded. This analysis indicated a positive association between the effect size and length of intervention (slope = 0.079, p = 0.05). We then repeated the analysis in which interventions shorter than the average (< 7 weeks) were excluded. This analysis demonstrated a negative association between the effect size and length of intervention (slope = − 0.038, p = 0.04). We found that frequency of delivery was significantly associated with the effect size (p = 0.03); MBIs delivered weekly produced stronger effects than those delivered more frequently. There were few indications for the effect size to be associated with other intervention conditions, including format of administration, type of MBI, and assignment of self-practice (p > 0.05). In addition, we examined whether sample size, study quality, and attrition rate had an influence on the effect size. Sample size was found to be significantly related with the effect size (slope = − 0.002, p = 0.02); smaller sample sizes demonstrated greater reductions in depressive symptoms. There were few indications that the effect size was affected by study quality or attrition rate (p > 0.05).

Discussion

This meta-analytic review of 25 RCTs examined the efficacy of MBIs for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students. Of the 25 reviewed trials, over two-thirds (n = 19) produced significant reductions in depressive symptoms. Significant intervention effects have replicated across trials with MBSR, MBCT, and ACT. In the meta-analysis, all the MBIs produced positive effect sizes. The average effect size was moderate (0.52), which is comparable and even more favorable to those found in previous meta-analyses of MBIs for other populations (Abbott et al. 2014; Dhillon et al. 2017; Hofmann et al. 2010; Rogers et al. 2017). The mean effect sizes were quite robust in the influence analyses and heterogeneity remained low to moderate in most analyses. Although findings may be somewhat overestimated by small-sample studies, the adjusted effect size still provided strong indications to support the use of MBIs for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students. These results suggest that mindfulness-based interventions, which are thought to promote emotional stability through regulation of attention to the present experience and encouraging attitude of curiosity, openness, and acceptance, could indeed help university students prevent depressive symptoms and alleviate their suffering.

Our findings provided strong evidence that universal, selective, and indicated MBIs were all associated with significant reductions in depressive symptoms for university students. There was a relatively large effect size for indicated MBIs, while the effect sizes for universal and selective MBIs were considered small. These findings reinforce that MBIs could be effective for university students with a wide range of risk status. In particular, our analyses found that indicated MBIs produced greater effects as compared with universal MBIs. This has been supported by previous meta-analyses of other depression prevention programs, which showed evidence in favor of indicated interventions to universal ones (Horowitz and Garber 2006; Stice et al. 2009). The distress that characterizes individuals of indicated MBIs could motivate them to engage more effectively in the prevention programs, providing greater opportunities for symptom reduction (Stice et al. 2009). While we found indicated MBIs were more effective than universal MBIs, universal MBIs were still effective for reducing depressive symptoms relative to control conditions. Universal MBIs may have benefits beyond symptom reduction: they intervene with preventative inoculation for the whole population without identifying those at risk, they minimize the risk of stigmatizing factors that make individuals reluctant to participate in the intervention programs, and they could be embedded in current curriculums to be delivered in conjunction with other educational programs (Barrett et al. 2006; Tugade et al. 2004). Such advantages could make universal MBIs more acceptable, available, and cost-effective. In addition, despite few indications for selective MBIs to be different from either universal or indicated MBIs, selective MBIs were effective as well for reducing depressive symptoms relative to control conditions. In contrast to universal and indicated MBIs, selective MBIs were administered to individuals who have one or more known risk factor(s) of depression. Thus, indicated, selective and universal MBIs may be all appropriate for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students, depending on the context of particular participants.

Findings of this meta-analytic review indicated that MBIs with medium length (about 7 weeks) could be associated with optimal intervention effects. While prolonged MBIs within the optimal length could produce increased intervention effects, our analyses also highlighted that adverse effects could occur if the optimal length was surpassed. Theoretically, longer interventions provide participants with larger exposure to information, practice, reflection, and advice on attitudinal and behavioral change skills. However, extremely long programs may not appeal to the participants, resulting in greater attrition rates and smaller intervention effects. Participant compliance commonly attenuates as intervention continues. This may produce an influence on the intervention effects. On one hand, it may take time for the intervention conditions to show decreases in depressive symptoms relative to the control conditions. On the other hand, the intervention effects may be tapered over time as participant compliance begins to decrease. Thus, for extremely long MBIs, intervention effects could increase first and reach the strongest at some time amid the interventions, which then become smaller as the interventions continue. This is consistent with the results of a few other meta-analyses of depression prevention programs, which found that greater length was associated with smaller effects (Eng and Reime 2014; Sockol et al. 2013; Stice et al. 2009). Meanwhile, there is evidence that depressive symptoms may naturally remit over time (Kelly and Mezuk 2017). This natural decrease of depressive symptoms could also have an influence on the intervention effects. While there could be decreases in depressive symptoms for the intervention conditions, the control conditions may also show natural decreases in depressive symptoms in the long term. As a result, the decreases in the intervention conditions relative to the control conditions may attenuate over time as depressive symptoms in the control conditions begin to remit. As we found optimal intervention effects exhibited for MBIs with medium length, those developed in very brief or extremely long versions may not be recommended for university students.

Supports were exhibited for the hypothesis that greater effects would emerge for female than male students. This occurs possibly because of the higher levels of depressive symptoms and greater prevalences of depression experienced by female than male students (Puthran et al. 2016). Our analyses have found that high-risk students of indicated MBIs were associated with larger reductions in depressive symptoms. Another possible explanation is that female students may respond more favorably than male students to the intervention they have received. Compared with male students, female students appear to have more engagement in the intervention content and are more likely to discuss sensitive issues that may negatively affect their emotions (Brunwasser et al. 2009; Stice et al. 2009). Such a difference in the response may contribute to an excess of the intervention effects for female students. While MBIs could be a favorable approach for female students, these data also imply the need for more effective interventions to target male students.

Another novel contribution was that MBIs delivered weekly were more effective than those delivered more frequently, implying that higher-intensity MBIs may not be recommended for university students. One possible explanation for this finding may be that higher-intensity MBIs could lead to adverse effects as participants may need sufficient time between sessions to absorb the knowledge and practice the skills. This is particularly true for university students who commonly have a crowded agenda. Another interpretation may be that MBIs delivered weekly were more likely to have medium lengths that accompanied the optimal intervention effects. Our analyses have indicated that MBIs with medium length (about 7 weeks) could produce the largest effects. In addition to MBSR and MBCT that typically lasted for 8 weeks and were delivered on a weekly basis, other weekly delivered MBIs in this meta-analytic review also tended to have medium lengths. In contrast, those delivered more frequently tended to have more extreme lengths that were either too short or too long. These MBIs have been suggested by our analyses to be associated with smaller effects.

Our analyses found that small sample sizes were associated with greater intervention effects. This could mean that meta-analysis findings may be overestimated by larger effects of those small-sample studies. Such small-study effects are common in meta-analyses (Sterne et al. 2000; Thornton and Lee 2000). This occurs in part because small sample sizes lead to insufficient statistical power and significance would be reached only if chance exaggerates any true difference (Angell 1989; Newcombe 1987). This will result in publication bias as small studies are more likely to be published when they report significant results. In this meta-analytic review, 16 out of 25 trials had a sample size smaller than 100 and our analyses did indicate small sample bias for the reviewed studies. After adjusting for possible publication bias, the overall mean effect size turned somewhat smaller but continued to be significant. These findings suggest that MBIs could be proposed as a reliable candidate for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students.

Limitations and Future Research

Our findings may be limited to the small sample sizes and suboptimal study quality of the included trials. Most of the trials had small sample sizes and showed high risk of bias in 2 domains or more following the Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool. As indicated by our and previous meta-analyses, the inclusion of smaller-sample and lower-quality studies may result in an inflated estimate of the efficacy of assessed interventions (Cuijpers et al. 2010). It would be necessary for future trials to use larger sample sizes and more rigorous designs.

This meta-analytic review was limited to the examination of short-term efficacy of MBIs. Given the frequent relapse of depressive symptoms, it is important to evaluate the length of any positive effects of MBIs. Such information could help understand the cost-versus-benefit ratios of these programs. Unfortunately, follow-up effects were not possible to be assessed in this meta-analysis, owing to insufficient follow-up data and variable follow-up intervals. When the literature matures to include more sufficient trials, a further meta-analytic review would be valuable to determine the follow-up efficacy of MBIs for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students.

While MBIs were found in the current analysis to be effective for the prevention of depressive symptoms in university students, different students may respond differently, and some MBIs may produce more favorable results. A range of potential moderators were identified in this meta-analytic review and it would be helpful for future trials to incorporate features associated with stronger effects. For instance, future MBIs could be developed in medium length and delivered on a weekly basis to target female students with elevated depressive symptoms. However, these findings were based on subgroup and meta-regression analyses, which only provided correlational associations. Future research may experimentally manipulate key moderators (e.g., length of intervention, frequency of delivery, gender of participants, and participant risk status) to examine if the moderator effects are real with causal relations. Meanwhile, it is noteworthy that a number of trials employed multifaceted interventions (e.g., MBSR, MBCT, and ACT) that combined mindfulness with other components. We were unable to conclude whether the observed effect size was attributable to the mindfulness rather than other components. It would be useful for future trials to determine whether incorporation of other components would truly contribute to additional effects as compared with mindfulness alone. We were also unable to assess whether baseline depression score (initial depression severity) was associated with the effect size as it was measured by a wide array of instruments. Baseline depression score could exert an influence on the intervention effects, which should be taken into account and further investigated. For instance, it is likely that the larger interventions effects for indicated trials could be ascribed to an average higher level of baseline depression score for the participants. This would create more room for an intervention effect to occur among them, as compared with those who already have a low level of depressive symptoms. In addition, non-specific characteristics (e.g., socioeconomic status, perceived social support, and coping ability) that have shown significant associations with depression among university students were not assessed as most studies provided insufficient information on these data (Hefner and Eisenberg 2009; Ibrahim et al. 2013b; Mahmoud et al. 2012). It would be beneficial for future trials to investigate whether these characteristics would moderate the effects of MBIs for the prevention of depressive symptoms in university students.

Furthermore, although the overall number of studies included in this meta-analysis is favorable to previous meta-analyses of MBIs for other populations (Abbott et al. 2014; Dhillon et al. 2017; Strauss et al. 2014), several of the subgroup analyses were based on a small number of studies. For instance, there were only three trials targeting first-year students, four trials targeting medical students, three trials without self-practice assignments, and three trials categorized as high-quality studies. The lack of statistical power in these subgroups may result in the failure to find significant differences between subgroups. Because of these concerns, findings with respect to these moderator analyses should be interpreted with caution.

Finally, this meta-analytic review was limited to trials assessing the efficacy of MBIs compared with inactive control conditions (e.g., waiting list, no-intervention, assessment-only, and usual care). Head-to-head trials would be necessary to establish the comparative effects of MBIs and other psychological interventions. And it is hoped that when a sufficient and larger number of studies are available, a comprehensive review would be valuable to synthesize the efficacy of MBIs for prevention of depressive symptoms in university students, particularly compared with active control conditions.

References

Articles included in the meta-analysis are marked by *.

Abbott, R. A., Whear, R., Rodgers, L. R., Bethel, A., Thompson, C. J., Kuyken, W., et al. (2014). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness based cognitive therapy in vascular disease: a meta-analytic review of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 76(5), 341–351.

Adams, T. B., Wharton, C. M., Quilter, L., & Hirsch, T. (2008). The association between mental health and acute infectious illness among a national sample of 18- to 24-year-old college students. Journal of American College Health, 56(6), 657–664.

Angell, M. (1989). Negative studies. New England Journal of Medicine, 321(7), 464–466.

Astin, J. A. (1997). Stress reduction through mindfulness meditation: effects on psychological symptomatology, sense of control, and spiritual experiences. Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics, 66(2), 97–106.

Barrett, P. M., Farrell, L. J., Ollendick, T. H., & Dadds, M. (2006). Long-term outcomes of an Australian universal prevention trial of anxiety and depression symptoms in children and youth: an evaluation of the friends program. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35(3), 403–411.

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., et al. (2010). Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology Science & Practice, 11(3), 230–241.

Blanck, P., Perleth, S., Heidenreich, T., Kroger, P., Ditzen, B., Bents, H., et al. (2018). Effects of mindfulness exercises as stand-alone intervention on symptoms of anxiety and depression: Systematic meta-analytic review. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 102, 25–35.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Brunwasser, S. M., Gillham, J. E., & Kim, E. S. (2009). A meta-analytic review of the Penn Resiliency Program's effect on depressive symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(6), 1042–1054.

Calear, A. L., & Helen, C. (2010). Systematic review of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for depression. Journal of Adolescence, 33(3), 429–438.

*Cavanagh, K., Strauss, C., Cicconi, F., Griffiths, N., Wyper, A., & Jones, F. (2013). A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(9), 573–578.

Cavanagh, K., Strauss, C., Forder, L., & Jones, F. (2014). Can mindfulness and acceptance be learnt by self-help?: a systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness and acceptance-based self-help interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(2), 118–129.

*Chen, Y., Yang, X., Wang, L., & Zhang, X. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of the effects of brief mindfulness meditation on anxiety symptoms and systolic blood pressure in Chinese nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 33(10), 1166–1172.

Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cohen, J. S., & Miller, L. J. (2009). Interpersonal mindfulness training for well-being: a pilot study with psychology graduate students. Teachers College Record, 111(12), 2760–2774.

Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Bohlmeijer, E., Hollon, S. D., & Andersson, G. (2010). The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychological Medicine, 40(2), 211–223.

Deeks, J. J., Higgins, J. P. T., & Altman, D. G. (2011). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In J. P. T. Higgins, ,& S. Green, S. (Eds). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed March 2011.

*Delgado-Pastor, L. C., Ciria, L. F., Blanca, B., Mata, J. L., Vera, M. N., & Vila, J. (2015). Dissociation between the cognitive and interoceptive components of mindfulness in the treatment of chronic worry. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 48, 192–199.

Dersimonian, R., & Laird, N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials, 7(3), 177.

Dhillon, A., Sparkes, E., & Duarte, R. V. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: a meta-analytic review. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1421–1437.

*Dundas, I., Binder, P. E., Hansen, T., & Stige, S. H. (2017). Does a short self-compassion intervention for students increase healthy self-regulation? A randomized control trial. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58(5), 443–450.

Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and Fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463.

*Dvorakova, K., Kishida, M., Li, J., Elavsky, S., Broderick, P. C., Agrusti, M. R., et al. (2017). Promoting healthy transition to college through mindfulness training with first-year college students: pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health, 65(4), 259–267.

Dyson, R., & Renk, K. (2006). Freshmen adaptation to university life: depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(10), 1231–1244.

Eisenberg, D., & Chung, H. (2012). Adequacy of depression treatment among college students in the United States. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(3), 213–220.

Eng, J. J., & Reime, B. (2014). Exercise for depressive symptoms in stroke patients: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(8), 731–739.

*Eustis, E. H., Hayes-Skelton, S. A., Orsillo, S. M., & Roemer, L. (2018). Surviving and thriving during stress: a randomized clinical trial comparing a brief web-based therapist-assisted acceptance-based behavioral intervention versus waitlist control for college students. Behavior Therapy, 49(6), 889-903.

*Falsafi, N. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness versus Yoga: effects on depression and/or anxiety in college students. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 22(6), 483–497.

Farabaugh, A., Bitran, S., Nyer, M., Holt, D. J., Pedrelli, P., Shyu, I., et al. (2012). Depression and suicidal ideation in college students. Psychopathology, 45(4), 228–234.

*Gallego, J., Aguilar-Parra, J. M., Cangas, A. J., Langer, A. I., & Manas, I. (2015). Effect of a mindfulness program on stress, anxiety and depression in university students. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, E109.

Garlow, S. J., Rosenberg, J., Moore, J. D., Haas, A. P., Koestner, B., Hendin, H., et al. (2008). Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depress Anxiety, 25(6), 482–488.

Gotink, R. A., Chu, P., Busschbach, J. J., Benson, H., Fricchione, G. L., & Hunink, M. G. (2015). Standardised mindfulness-based interventions in healthcare: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs. Plos One, 10(4), e0124344.

Gregoire, S., Lachance, L., Bouffard, T., & Dionne, F. (2018). The use of acceptance and commitment therapy to promote mental health and school engagement in university students: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 49(3), 360–372.

Gress-Smith, J. L., Roubinov, D. S., Andreotti, C., Compas, B. E., & Luecken, L. J. (2015). Prevalence, severity and risk factors for depressive symptoms and insomnia in college undergraduates. Stress Health, 31(1), 63–70.

*Gu, Y., Xu, G., & Zhu, Y. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for college students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 22(4), 388–399.

*Hall, B. J., Xiong, P., Guo, X., Sou, E. K. L., Chou, U. I., & Shen, Z. (2018). An evaluation of a low intensity mHealth enhanced mindfulness intervention for Chinese university students: a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Research, 270, 394–403.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. Encyclopedia of Psychotherapy, 9(1), 1–8.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1984(24), 25–42.

Hefner, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2009). Social support and mental health among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 491–499.

Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., et al. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ British Medical Journal, 343(7829), 889–893.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183.

*Holly, H., & Yelena, O. (2017). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based stress reduction bibliotherapy: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. Trials, 73(6), 626–637.

Horowitz, J. L., & Garber, J. (2006). The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 401–415.

Hysenbegasi, A., Hass, S. L., & Rowland, C. R. (2005). The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. Journal of Mental Health Policy & Economics, 8(3), 145–151.

Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., Adams, C. E., & Glazebrook, C. (2013a). A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(3), 391–400.

Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., & Glazebrook, C. (2013b). Socioeconomic status and the risk of depression among U.K. higher education students. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric, 48(9), 1491–1501.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice, 10(2), 144–156.

*Kang, Y. S., Choi, S. Y., & Ryu, E. (2009). The effectiveness of a stress coping program based on mindfulness meditation on the stress, anxiety, and depression experienced by nursing students in Korea. Nurse Education Today, 29(5), 538–543.

Kelly, K. M., & Mezuk, B. (2017). Predictors of remission from generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 208, 467–474.

Kenney, B. A., & Holahan, C. J. (2008). Depressive symptoms and cigarette smoking in a college sample. Journal of American College Health, 56(4), 409–414.

Keyes, C. L., Eisenberg, D., Perry, G. S., Dube, S. R., Kroenke, K., & Dhingra, S. S. (2012). The relationship of level of positive mental health with current mental disorders in predicting suicidal behavior and academic impairment in college students. Journal of American College Health, 60(2), 126–133.

*Ko, C. M., Grace, F., Chavez, G. N., Grimley, S. J., Dalrymple, E. R., & Olson, L. E. (2018). Effect of seminar on compassion on student self-compassion, mindfulness and well-being: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of American College Health, 66(7), 537–545.

*Levin, M. E., Haeger, J. A., Pierce, B. G., & Twohig, M. P. (2016). Web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for mental health problems in college students: a randomized controlled trial. Behavior Modification, 41(1), 141–162.

Mahmoud, J. S., Staten, R., Hall, L. A., & Lennie, T. A. (2012). The relationship among young adult college students' depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(3), 149–156.

*McIndoo, C. C., File, A. A., Preddy, T., Clark, C. G., & Hopko, D. R. (2016). Mindfulness-based therapy and behavioral activation: a randomized controlled trial with depressed college students. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 118–128.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), 264–269.

*Moir, F., Henning, M., Hassed, C., Moyes, S. A., & Elley, C. R. (2016). A peer-support and mindfulness program to improve the mental health of medical students. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 28(3), 293–302.

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York: The Guilford Press.

Moussavi, S., Chatterji, S., Verdes, E., Tandon, A., Patel, V., & Ustun, B. (2007). Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys. Lancet, 370(9590), 851–858.

Mrazek, P. J., & Haggerty, R. J. (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press.

Murray, C. J., & Lopez, A. D. (1997). Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet, 349(9064), 1498–1504.

Newcombe, R. G. (1987). Towards a reduction in publication bias. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 295(6599), 656–659.

*Nidich, S. I., Rainforth, M. V., Haaga, D. A., Hagelin, J., Salerno, J. W., Travis, F., et al. (2009). A randomized controlled trial on effects of the transcendental meditation program on blood pressure, psychological distress, and coping in young adults. American Journal of Hypertension, 22(12), 1326–1331.

*Panahi, F., & Faramarzi, M. (2016). The effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on depression and anxiety in Women with Premenstrual Syndrome. Depression Research and Treatment, 2016, 1–7.

Puthran, R., Zhang, M. W., Tam, W. W., & Ho, R. C. (2016). Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: a meta-analysis. Medical Education, 50(4), 456–468.

*Rasanen, P., Lappalainen, P., Muotka, J., Tolvanen, A., & Lappalainen, R. (2016). An online guided ACT intervention for enhancing the psychological wellbeing of university students: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 78, 30–42.

Reyes-Rodriguez, M. L., Rivera-Medina, C. L., Camara-Fuentes, L., Suarez-Torres, A., & Bernal, G. (2013). Depression symptoms and stressful life events among college students in Puerto Rico. Journal of Affective Disorders, 145(3), 324–330.

Rogers, J. M., Ferrari, M., Mosely, K., Lang, C. P., & Brennan, L. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for adults who are overweight or obese: a meta-analysis of physical and psychological health outcomes. Obesity Reviews, 18(1), 51–67.

Rotenstein, L. S., Ramos, M. A., Torre, M., Segal, J. B., Peluso, M. J., Guille, C., et al. (2016). Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a meta-analytic review. Jama, 316(21), 2214–2236.

Salzer, M. S. (2012). A comparative study of campus experiences of college students with mental illnesses versus a general college sample. Journal of American College Health, 60(1), 1–7.

Shapiro, S. L., Oman, D., Thoresen, C. E., Plante, T. G., & Flinders, T. (2008). Cultivating mindfulness: effects on well-being. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(7), 840–862.

*Shapiro, S. L., Schwartz, G. E., & Bonner, G. (1998). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on medical and premedical students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(6), 581–599.

Sockol, L. E., Epperson, C. N., & Barber, J. P. (2013). Preventing postpartum depression: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1205–1217.

*Song, Y., & Lindquist, R. (2015). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness in Korean nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 35(1), 86–90.

Spijkerman, M. P. J., Pots, W. T. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Effectiveness of online mindfulness-based interventions in improving mental health: a meta-analytic review of randomised controlled trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 102–114.

Sterne, J. A., Gavaghan, D., & Egger, M. (2000). Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(11), 1119–1129.

Stice, E., Shaw, H., Bohon, C., Marti, C. N., & Rohde, P. (2009). A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 486–503.

Strauss, C., Cavanagh, K., Oliver, A., & Pettman, D. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Plos One, 9(4), e96110.

Taylor, B. L., Cavanagh, K., & Strauss, C. (2016). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in the perinatal period: a meta-analytic review. Plos One, 11(5), e0155720.

*Taylor, L., Strauss, C., Cavanagh, K., & Jones, F. (2014). The effectiveness of self-help mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in a student sample: a randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 63, 63–69.

Thompson, S. G., & Sharp, S. J. (1999). Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Statistics in Medicine, 18(20), 2693–2708.

Thornton, A., & Lee, P. (2000). Publication bias in meta-analysis: its causes and consequences. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(2), 207–216.

Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Feldman Barrett, L. (2004). Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72(6), 1161–1190.

*Warnecke, E., Quinn, S., Ogden, K., Towle, N., & Nelson, M. R. (2011). A randomised controlled trial of the effects of mindfulness practice on medical student stress levels. Medical Education, 45(4), 381–388.

Weitzman, E. R. (2004). Poor mental health, depression, and associations with alcohol consumption, harm, and abuse in a national sample of young adults in college. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 192(4), 269–277.

Wells, V. E., Klerman, G. L., & Deykin, E. Y. (1987). The prevalence of depressive symptoms in college students. Social Psychiatry, 22(1), 20–28.

*Weytens, F., Luminet, O., Verhofstadt, L. L., & Mikolajczak, M. (2014). An integrative theory-driven positive emotion regulation intervention. Plos One, 9(4), e95677.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Hao Sun from the Department of Epidemiology of the First Hospital of China Medical University for her helpful comments.

Funding

This study was funded by the Department of Education of Liaoning Province (grant number 2014 [108]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LM: designed and executed the study, performed the statistical analyses, and finished the initial version of this manuscript. YZ: collaborated in the process of literature reviewing, data coding, and statistical analyses. ZC: collaborated in the writing and revision of the final manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Liang Ma and Yingnan Zhang contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 31 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, L., Zhang, Y. & Cui, Z. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Prevention of Depressive Symptoms in University Students: a Meta-analytic Review. Mindfulness 10, 2209–2224 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01192-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01192-w