Abstract

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are in the fourth decade of adaptation and testing, yet little is known about their level of treatment fidelity. Treatment fidelity is a methodological strategy used to monitor and enhance the reliability and validity of behavioral interventions. The Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium (BCC) put forth recommendations covering five components of treatment fidelity: design, training, delivery, receipt, and enactment. We conducted a literature review to describe how these five components of treatment fidelity are reported in published main outcomes articles of MBI efficacy trials among adult participants. Our search yielded 202 articles, and we identified 25 (12%) described study treatment fidelity. All 25 studies reported on design, n = 24 (96%) reported on training, n = 23 (92%) reported on delivery, n = 23 (92%) reported on receipt, and n = 16 (64%) reported on enactment. Eleven (44%) articles analyzed measures of receipt and enactment with a participant outcome. Fourteen (56%) articles reported on all five fidelity components. There was high variation in the way each component was conducted and/or reported, making comparisons across articles difficult. To address the prevailing limitation that the majority of MBI efficacy studies did not detail treatment fidelity, we offer the Treatment Fidelity Tool for MBIs adapted from the BCC guidelines to help researchers monitor and report these methods and measures in a simple and standardized format. By using this tool, researchers have the opportunity to improve the transparency and interpretability of the MBI evidence base.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Treatment fidelity refers to methodology used to monitor and enhance the accuracy and consistency of a behavioral intervention (Bellg et al. 2004). Adequately monitoring and reporting treatment fidelity when publishing efficacy outcomes allows for assessment of whether observed treatment effects in an empirical trial are attributable to the intervention delivered (Carroll et al. 2007; Leeuw et al. 2009). Higher levels of treatment fidelity are associated with stronger, more interpretable, treatment outcomes and grant more confidence in specifying the underlying mechanisms of change (Carroll et al. 2007). Furthermore, only when treatment fidelity is executed with high integrity can researchers conclude that participant outcomes are due to the intervention curriculum and not random events. For example, if a program is not executed as intended, researchers run the risk of making a type III error (i.e., determining the program is not effective due to poor treatment fidelity or implementation failure), which incurs an economic and scientific burden (Gould et al. 2016; Breitenstein et al. 2010; Borrelli 2011). Reporting of treatment fidelity in empirical articles presenting behavioral intervention outcomes is not standard practice, drawing attention to an important weakness to address in behavioral science.

Guidelines for the assessment and practice of treatment fidelity in behavioral interventions have evolved over time, and various frameworks have been offered (e.g., Gould et al. 2016 and Lichstein et al. 1994). In 2004, the Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the National Institutes of Health Behavior Change Consortium (BCC) synthesized existing definitions, methodologies, and measurements across frameworks and put forth new recommendations for treatment fidelity among behavior change interventions (Bellg et al. 2004). NIH sponsored research must follow extensive policies and procedures to maintain scientific integrity and rigor (NIH 2012), including treatment fidelity. Thus, for the current review, we selected the NIH-developed BCC guidelines instead of others because they appear to be the most comprehensive to date and were compiled by expert consensus.

The BCC recommendations detail five components of treatment fidelity to be considered when monitoring and reporting efficacy of behavioral interventions: design, training, delivery, receipt, and enactment (Resnick et al. 2005; Bellg et al. 2004). Design, training, and delivery components focus on the treatment provider while receipt and enactment focus on the participant. Design involves methodological strategies to ensure that a study can test hypotheses in relation to underlying theories and clinical processes (i.e., the intervention is delivered in the same dose within and across conditions, and a plan is developed for implementation setbacks). Training involves strategies to ensure interventionists have been properly trained on delivering the intervention to the target population (i.e., standardize training using curriculum manuals, ensure provider skills acquisition, minimize drift in provider skills, and accommodate for provider differences). Delivery involves strategies to monitor the intervention to assure it is delivered as intended (i.e., control for provider differences, reduce differences in treatment delivery, ensure adherence to treatment protocol, and minimize contamination between conditions). Receipt involves strategies to monitor and enhance participants understanding and performance of intervention related skills and strategies during the period of intervention delivery (i.e., ensure participant comprehension including cognitive capacity and behavioral performance). Enactment involves strategies to monitor and enhance participants’ performance of intervention related skills and strategies in daily life outside of the intervention setting (i.e., ensure participants’ use of behavioral and cognitive skills). These fidelity components serve as guidelines that can be adapted for a variety of behavioral interventions. Newer behavioral interventions showing rapid growth and acceptance in scientific spheres and those gaining public appeal are in particular need of ensuring treatment fidelity in order to enhance confidence that scientific findings are actually due to the active ingredients of the intervention (Borrelli 2011), and to reduce the risk and costs of a type III error.

Mindfulness training is a relatively newer behavioral program that shows increasing promise for efficacy to improve stress-related ailments, psychiatric disorders, and disease symptoms (Black and Slavich 2016; Goyal et al. 2014; Hofmann et al. 2010; van der Velden et al. 2015; Black 2012, 2014; O'Reilly et al. 2014). Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) represent a family of programs developed with the goal of helping people cultivate an ongoing daily practice of mindfulness operationalized as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment” (Black 2012, 2014; Kabat-Zinn 2003). MBIs are part of a third wave of empirically tested psychotherapeutics. The first two—behavioral therapy and then cognitive behavioral therapy—focus on modification of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors whereas MBIs focus on developing metacognitive awareness, acceptance, and a non-reactive stance to those same experiential processes (Crane et al. 2017). Given the complex nature of delivering MBIs (e.g., interventionist mastery of concepts, embodied skills, and personal practice) and that high levels of treatment fidelity are associated with stronger program effects (Borrelli 2011), evaluating MBI treatment fidelity and how methods and measures account for participant outcomes is a logical next step in improving scientific rigor and interpretability of findings.

In order to validly and reliably test if and how variation in implementation is related to participant outcomes across trials, we first need to describe how treatment fidelity components and subcomponents are currently being conducted and reported in mindfulness literature. This information can foster an understanding about where implementation gaps exist and offer recommendations for improvement. For example, a study may have conducted treatment fidelity to the highest standard using the BCC framework but did not publish that information or published it separately from participant outcomes (e.g., Zgierska et al. 2017). Two recent systematic reviews of treatment fidelity have highlighted this gap in the fields of school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions (Gould et al. 2016) and pediatric obesity intervention trials (JaKa et al. 2016). Both reviews identified low and inconsistent reports across all treatment fidelity components and offered recommendations for researchers and clinicians to enhance the development and publication of their multicomponent treatment fidelity methods. Yet, neither developed a standardized protocol for practicing and reporting on treatment fidelity. Furthermore, Gould et al. (2016) found less than 20% of MBI programs delivered to youth reported any component of fidelity implementation beyond participant dosage. However, dosage is only one element of treatment fidelity and no similar examination has been conducted for adult samples, which is where the majority of empirical evidence in the mindfulness field has accumulated. One way to approach this implementation limitation is to establish measurable criteria and offer a reporting tool.

Our current review of the literature describes how RCT studies testing MBIs report on the five treatment fidelity components outlined by the BCC guidelines. Specifically, we (1) identify efficacy trials of established MBIs that report on study treatment fidelity within a published main outcomes article, (2) describe treatment fidelity methods and measures in these articles using the BCC guidelines, (3) determine if identified components of treatment fidelity were integrated in an analysis with participant outcomes, and (4) provide a treatment fidelity tool adapted from the BCC guidelines that we tailored for MBIs. Our proposed Treatment Fidelity Tool for Mindfulness Based Interventions is intended to help researchers and program developers monitor and report treatment fidelity using common methods and measures.

Method

Literature Search and Study Selection

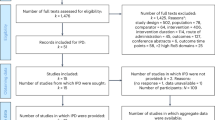

To identify published articles for inclusion in this methodology review, the authors determined the parameters for the search and the first author searched PubMed articles from 1966 (date of the first mindfulness publication) to February 27, 2017, using the following combined key words: clinical trial OR controlled trial AND mindfulness-based intervention. This was followed by a more specific search for Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction, OR Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy, OR Mindfulness Based Relapse Prevention, OR Mindful Awareness Practices, OR Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement, OR Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training. The first author read titles and abstracts of approximately 202 retrieved articles and determined 116 did not meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) an efficacy trial of an established MBI and (2) participants 18 years of age or older. The first author then downloaded the remaining 86 articles and searched within their full text to determine whether they included (3) main outcomes from an experimental trial (secondary outcome articles were excluded to minimize redundancy) and (4) a description of treatment fidelity. Inclusion criteria for this review were set to maximize similarity of design and participants to most accurately compare articles. While it is essential for all behavioral interventions to conduct treatment fidelity, regardless of study design (e.g., experimental vs. quasi-experimental) and study phase (e.g., efficacy vs. effectiveness), we only included MBI experimental efficacy trials (i.e., RCTs). This criterion permitted a critical review and comparison of studies that have the most impact on evidence-based practice, robust interpretations of validity, and similar resources and requirements to conduct treatment fidelity. Study authors were not contacted for additional information, as the purpose of this review was to identify how treatment fidelity is commonly reported within available mindfulness literature. Twenty-five articles met all criteria and are included in this review.

Data Abstraction

The first author abstracted relevant data from each article under the following domains. “Sample” included participant demographic information and target outcome (i.e., reduction of substance use or substance use disorder symptoms, reduction of high blood pressure). “Study design” included study information on randomization and definition of treatment groups. Under treatment fidelity, “design” included any information about the program’s intervention and control condition(s), development of curriculum, and any mention of program adaptation. “Training” included any information about how the interventionists were initially trained and specifically trained on intervention curriculum content and delivery. “Delivery” included any methods of monitoring, evaluating, and supervising interventionists for competence and adherence during the trial. “Receipt” included any information about participants’ attendance, engagement, and acceptance. “Enactment” included any information about participant application of intervention skills in daily life. “Treatment Fidelity Measures Used in Participant Outcome Analyses” included information on use of identified treatment fidelity measures in participant outcome analyses, such as number of sessions attended as predictor for time to relapse. The first author checked abstracted data for errors and considered a treatment fidelity component to be present if at least one subcomponent strategy was described in the article.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [Table 2].

Results

Our literature search identified approximately 202 articles of which 25 (12%) were judged to meet study criteria representing a main outcomes article from a MBI RCT for participants ≥ 18 years old that described study treatment fidelity. That is, 116 of 202 (57%) were not RCTs for adults, and 61 of the remaining 86 (71%) experimental trials reviewed did not clearly describe treatment fidelity within a main outcomes article. Of the 25 studies included in this review, 9 reported on Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), 11 on Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), 2 on Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP), 2 on Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE), and 1 on Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT). Table 1 shows that 25 articles (100%) reported on design, 24 (96%) reported on training, 23 (92%) reported on delivery, 23 (92%) reported on receipt, and 16 (64%) reported on enactment. Fourteen (56%) reported on all five components. Eleven (44%) articles analyzed measures from receipt and enactment with participant outcome measures. Overall, we found variation in (1) the methods and measures used and the details provided for each treatment fidelity component, and (2) the report and results of analyses linking treatment fidelity components and main outcome measures. Below we detail specific consistencies and inconsistencies in the reporting of treatment fidelity in MBI efficacy trials. Our inclusions of quotations from original articles are used to demonstrate the various reporting styles used when describing treatment fidelity components. See Table 2 for full details.

Design

Design was reported in 25 (100%) articles. All articles included the name of the formal group-based intervention program by referencing the program developer and year. All articles included program duration in number of weeks, sessions per week, and number of hours per session. Duration, frequency, and time per session ranged from 6-weekly 1.5-h sessions to 10-weekly 2-h sessions. The most common format (46% of studies reviewed) was 8-weekly 2-h sessions. All articles included information on program adaptations of group size, duration, and target population, if applicable. For example, Geschwind et al. (2012) reported using MBCT by Segal et al. (2002) for 8-weekly 2.5-h sessions with 10–15 participants who had residual symptoms and history of depression.

Inclusion of study rationale varied among MBI program adaptations and comparison groups. For example, one article reportedly adapted the original MBCT program by Segal et al. (2012) for participants with treatment resistant depression, cited curriculum publications, and described adaptations (e.g., “shortened meditations to max 30 minutes, emphasize mindful movement, explore barriers to practice and focus on acceptance of emotional events”) (Eisendrath et al. 2016). In contrast, another article reportedly adapted the MBCT manual by Segal et al. (2012) with minor alterations to address suicidality (e.g., “introduction of a crisis plan and cognitive components addressing suicidal cognitions and hopefulness”) (Hargus et al. 2010). Additionally, details provided for comparison/control groups varied. For example, Hargus et al. (2010) reported using a wait-list control or treatment as usual comparison group and provided few details for what that entailed, while Gross et al. (2010) reported using a dose-matched attention control group and provided equivalent information and citations for both groups.

Training

Training was reported in 24 (96%) articles. All but one article (van Son et al. 2013) detailed the interventionist’s training, background, and/or experience (e.g., MBSR certified, LSW interventionist with training in MBCT). However, these details varied across articles. For example, Carmody et al. (2011) reported that “Classes were conducted by Center of Mindfulness instructors” whereas Cherkin et al. (2016) reported on the number of interventionists, years of experience delivering the intervention, and where the interventionist received certification for their respective intervention. The details on interventionist training and experiences also varied between groups within the same study. For example, Hughes et al. (2013) reported a clinical psychologist with MBSR training delivered program sessions but did not detail the credentials of the interventionist who delivered the control condition, whereas Garland et al. (2014) reported a nurse trained in MBSR with over 10 years of experience delivered program sessions and a doctoral-level student in clinical psychology with CBT-I training delivered the control condition.

Beyond interventionist qualifications, information about the interventionist training on the program-specific curriculum was infrequently reported or provided with little detail. For example, one article reported holding a 7-day intensive training for interventionists (Segal et al. 2010) while another reported assessing interventionists for competence and adherence and interventionists only progressed to delivering the intervention if all domains were clearly established (Kuyken et al. 2015). McManus et al. (2012) reported interventionists received preliminary supervision. While other articles only stated that MBSR interventionists were simply “in agreement with content and format of the MBSR course manual” (de Vibe et al. 2013) or did not report this element of treatment fidelity (Williams et al. 2014).

Delivery

Delivery was reported in 23 (92%) articles. Fifteen studies (65% of those reporting delivery) reported one or more subcomponent of delivery including recording intervention sessions (using either audio or video), reviewing and rating recordings for interventionist adherence and competency, and/or providing interventionists with supervisor feedback in real-time. Nine (39% of those reporting delivery) articles reported on at least one subcomponent such as interventionists received weekly supervision (Bowen et al. 2009) or were monitored for adherence to treatment protocol (Barnhofer et al. 2009). Two articles did not report on any subcomponent of delivery (Carmody et al. 2011; Palta et al. 2012). Among studies that included an active control group, all ten (40%) articles described equivalent methods of monitoring the delivery of both groups (Cherkin et al. 2016; Eisendrath et al. 2016; Garland et al. 2016; Garland et al. 2014; Gross et al. 2010; Hoge et al. 2013; Hughes et al. 2013; Shallcross et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2014; Kristeller et al. 2013).

Descriptions of how treatment fidelity delivery was assessed varied greatly in both detail and rigor. For example, Bowen et al. (2014) reported, “Treatment adherence to RP and MBRP established with weekly supervision and review of audio recorded sessions. Competence evaluated by random selection of 50% of sessions from 8 MBRP cohorts, each rated by 2 of 3 independent raters… Raters attended practice and review meetings until acceptable reliability was achieved, with regular recalibration sessions to prevent drift. Using 1-way random-effects models, interrater consistency was adequate for mean ratings of competence (intraclass correlation coefficient, 0.77), with mean (SD) competence rated between adequate and good (4.63[0.42])” on a MBRP-AC, 7 point scale an independent person to rate intervention sessions using assessment scales (e.g., MBRP-AC: MBRP Adherence and Competence Scale in (Bowen et al. 2014)). In contrast, de Vibe et al. (2013) reported, “Instructors consulted with each other after every class to ensure programme fidelity.”

Receipt

Receipt of the MBI was identified in 23 (92%) articles. Seventeen (74%) of those articles explicitly reported they collected participant attendance at intervention sessions. All but two of those (Eisendrath et al. 2016; Kristeller et al. 2013) reported average proportion of participant session attendance. Six (26%) articles implicitly reported they collected participant attendance to intervention sessions (e.g., attending at least 4 sessions was considered minimal dose for Bondolfi et al. (2010)). Furthermore, two articles reported they collected participant ratings on intervention credibility (Shallcross et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2014). One article reported they evaluated level of participation beyond attendance (Palta et al. 2012). Three (12%) of all articles reported more than one of the above methods (Palta et al. 2012; Shallcross et al. 2015; Williams et al. 2014).

While nearly all articles reported collecting measures that we considered treatment receipt, the measures and definitions varied. For example, the proportion of sessions participants were required to attend per protocol completion ranged across studies from 12.5% or 1 of 8 sessions (e.g., Hoge et al. 2013) to 62.5% or 5 of 8 sessions (e.g., Garland et al. 2014). Furthermore, Shallcross et al. (2015) reported using the Treatment Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire, which is a validated measure that assesses participant perspective and fit of treatment. In contrast, other articles reported collecting an observational evaluation of participation completed by a study team member using a checklist (Palta et al. 2012) or provided an unclear description such as “rated credibility of treatment on 0–10 scales” (Williams et al. 2014).

Enactment

Enactment of the MBI was reported in 16 (64%) articles, 12 of which (75%) reported collecting mindfulness practice logs. Five articles reported collecting Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), a reliable and valid instrument for assessing five distinct elements of mindfulness across diverse populations (Bowen et al. 2009; de Vibe et al. 2013; Eisendrath et al. 2016; Garland et al. 2016; McManus et al. 2012). Two articles reported collecting Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS), a reliable and valid instrument for assessing trait mindfulness across diverse populations (Gross et al. 2010; Moynihan et al. 2013). One article reported a post-hoc questionnaire on mindfulness practice across three study periods (Bondolfi et al. 2010). Four (24% of those reporting any aspect of enactment) articles reported collecting both practice logs and FFMQ or MAAS (Bowen et al. 2009; de Vibe et al. 2013; Gross et al. 2010; Eisendrath et al. 2016).

While we identified three measures used across 16 studies to assess levels of enactment, there was some variation in how articles defined similar measures, such as practice logs. For example, one article calculated total number of minutes per day (Geschwind et al. 2012), another calculated number of days and hours per week (Barnhofer et al. 2009), and another calculated a practice score (0–20) based on four questions pertaining to the past month (de Vibe et al. 2013). Depending on the study design and resources, these measures were collected at only one or up to four time points.

Treatment Fidelity Measures Used in Participant Outcome Analyses

Eleven (44%) articles tested for an association between a treatment fidelity measure and study outcome. All measures of treatment fidelity that were identified in analyses with participant outcomes were from the components of receipt (e.g., session attendance) and enactment (e.g., FFMQ and practice logs). Four reported correlation analyses using receipt or enactment measures (Eisendrath et al. 2016; Garland et al. 2016; Gross et al. 2010; Kristeller et al. 2013). Two reported moderation with interaction term in regression analyses using both receipt and enactment measures (de Vibe et al. 2013; Shallcross et al. 2015). One reported moderation analyses using median split of enactment measures (Lengacher et al. 2014; Shallcross et al. 2015). Two reported mediation analyses using enactment measures (Eisendrath et al. 2016; McManus et al. 2012). One reported t test analyses using enactment measures (Geschwind et al. 2012; Moynihan et al. 2013). One reported hazard ratio analyses using receipt measures (Kuyken et al. 2015). One reported Fischer’s exact test using enactment measures (Bondolfi et al. 2010).

Higher reports of treatment fidelity did not always associate with greater improvement in participant outcomes. Articles that tested the association between receipt and enactment measures with main outcome measures using correlation and t tests found a significant positive association between treatment fidelity and greater improvement in participant outcomes. However, articles that reported testing associations between receipt and enactment measures with main outcome measures using hazard ratio and Fischer’s exact found nonsignificant differences between intervention groups. Articles that reported testing receipt and enactment measures with main outcome measures using mediation and moderation analyses found mixed significant results. For example, one article reported greater changes in FFMQ global scores mediated the relation between group condition (MBCT vs. Usual Services) and improvements in health anxiety among a group of adults diagnosed with hypochondriasis (McManus et al. 2012). While another article reported greater changes in FFMQ global scores did not mediate the relation between group (MBCT vs. Health Education Program) and observed improvements in depressive symptoms among a sample of adults diagnosed with treatment resistant depression and failed anti-depressant medication treatment (Eisendrath et al. 2016).

Discussion

We reviewed reports of treatment fidelity in the MBI efficacy literature. Only 25 (12%) of the 202 MBI articles identified represented RCTs testing a MBI among adults that described treatment fidelity in a main outcomes paper. Among articles that met all inclusion criteria, there was high variation in (1) the way each component was monitored and reported as well as (2) the report and results of analyses linking treatment fidelity components and trial outcome measures. Therefore, as a possible solution to the field’s general lack of reporting treatment fidelity with consideration of limited journal space, we developed a treatment fidelity tool to facilitate consistent collection and report of these methods and measures in published studies.

Our findings indicate that better reporting of MBI treatment fidelity is needed. Under the assumption that less than a third of the identified MBI efficacy studies (25 of 86) conducted treatment fidelity, we conclude that there is some threat to robust interpretations of MBI trials given the inherent influence of treatment fidelity on reliability and validity of findings. However, we only included RCTs that reported on treatment fidelity in the main outcomes article, which is not yet required by journals. Thus, we cannot assume that lack of specifying treatment fidelity methods and related findings in published articles means that such methods were not used and/or data collected. Given that behavioral intervention trial findings have limited interpretation value if they lack treatment fidelity (Forgatch et al. 2005), it is important researchers report methods and measures of treatment fidelity in main outcome articles to inform readers if the intervention was implemented as designed and then accurately tested in the experimental trial (Resnick et al. 2005). Similar to the CONSORT statement and checklist that over 400 journals promote for detailing the design of RCTs (Jull and Aye 2015; Schulz et al. 2010), we recommend improving reporting standards on treatment fidelity when publishing MBI efficacy studies as well as other behavioral interventions.

Using the BCC guidelines, we found consistencies and inconsistencies in how authors described treatment fidelity methods and measures. Articles reviewed were largely consistent in detailing the treatment fidelity component of design. While one to two subcomponents of training, delivery, and receipt were reported by majority of articles, the details provided regarding methods and measures varied considerably (e.g., interventionist rated using validated adherence and competence assessment scales by multiple independent persons vs. interventionist-to-interventionist consultation for monitoring program delivery); thus, limiting interpretation of the effect treatment fidelity may have on intervention efficacy. Enactment was least often reported in articles. This may lead to a limited understanding of potential underlying mechanisms of change in producing beneficial outcomes given the distinction of enactment measuring outside intervention practice versus receipt measuring within intervention exposure. Our findings are comparable to those of a systematic review that also used the BCC guidelines to identify reporting of treatment fidelity in the field of obesity interventions (JaKa et al. 2016). JaKa et al. also found reporting of design elements to be most common practice, while consistent report of elements in training, delivery, receipt, and enactment were lacking. Eighty-seven percent of studies they reviewed reported less than half of the BCC items. While our findings indicate that the proportions of components reported are higher in MBI RCTs, this is likely because we only included studies that described treatment fidelity and considered a component was reported if at least one subcomponent was present. However, paucity of treatment fidelity reports in published literature remains a weakness across these behavioral interventions, which limits our ability to conclude an intervention is efficacious due to the intended program elements (Breitenstein et al. 2010; Gould et al. 2016; Lichstein et al. 1994).

From the BCC guidelines, we identified two measurement gaps in MBI literature. First, no studies reported assessing participants’ understanding of mindfulness, which is described by the BCC as a subcomponent in receipt. To date, researchers tend to gauge participant receipt through utilization of mindfulness by collecting self-report logs on the type and duration of practices between-sessions and at post-intervention. However, we believe the quality of one’s practice is limited to their comprehension and competence, such that measuring the quantity of home practice does not gauge the degree to which participants properly comprehend and adhere to the principles of mindfulness practice (Lloyd et al. 2017). To our knowledge, there is no tool that directly assesses whether participants understand and/or demonstrate appropriate utilization of mindfulness skills. Example items may include, “True or False: My mind should be completely clear when I meditate” (answer: false, this is a common misconception) and “List the components in the Triangle of Awareness” (answer: thoughts, emotions, physical sensations). The development of such a tool could be useful in interpreting if and how participant’s understanding of mindfulness principles and practices associate with intervention utilization and outcomes. Second, direct measures of program acceptability and satisfaction were not reported in any of these articles and thus unable to be assessed with participant outcomes. The closest approximation of this element, if present, was often found in results under “Feasibility/Acceptability” where authors reported information on drop-out, attendance, and self-report practice (e.g., Garland et al. 2014). However, we believe these objective measures do not encompass participants’ subjective experience of MBIs and individual differences in mindfulness uptake (e.g., validated measures of participant satisfaction and program acceptability). This may be an important oversight if program acceptability functions as a mediating variable or necessary but insufficient element between MBI and change in treatment outcomes. To the best of our knowledge, no published research has examined whether measures of program understanding and acceptability mediate MBI participant outcomes.

We found that receipt and enactment components of treatment fidelity were integrated in an analysis of participant outcomes in 44% of included articles. However, across articles there were inconsistent findings in the relation between degree of treatment fidelity and improvement on main outcome measures, despite the use of similar measures and statistical methods. This aligns with a review by Gould et al. (2016) who used a less common treatment fidelity guideline (i.e., CORE: conceptualize core components, operationalize and measure, run analyses and report/review findings, enhance and refine) to assess rigor and reporting of treatment fidelity among school-based mindfulness programs for youth. We found similar reports regarding what Gould et al. described as participant dosage, such that the majority of articles reported information on attendance (% of sessions attended) and outside practice (# days/week or # minutes/day). Furthermore, Gould et al. identified six or 13% of articles they reviewed associated treatment fidelity measures of participant dosage with an intervention outcome, and the significance of those results was also mixed. For example, five of the six studies found at least one, but not all, element of attendance or practice was significantly associated with participant outcomes. However, each program utilized their own dosage cutoff (e.g., 4 or more days per week, 20+ minutes per day, 70% session attendance, etc.) and it is unclear whether those cutoffs were set a priori. One plausible reason for mixed findings regarding treatment fidelity used in outcome analyses could be the non-standard collection and definition of mindfulness practice logs and required session attendance. Mindfulness practice logs are inherently subject to report bias, and inconsistent definitions of practice (e.g., minutes vs. days) and attendance (e.g., 1 vs. 4 sessions required) may restrict our understanding of participant outcomes related to dosage. While comparing efficacy of MBIs across trials would be useful in evaluating treatment effects (e.g., identify how much practice is “needed” to significantly improve outcomes for different conditions and populations), such an assessment requires that MBIs incorporate use of consistent definitions, measures, and reporting of treatment fidelity components.

To help researchers conduct and then report treatment fidelity in a simple and standardized format, we developed a Treatment Fidelity Tool for MBIs (Table 3). This tool encompasses 15-items, each informed by our synthesis of MBI RCTs using the BCC framework. We recommend researchers use this tool to consistently assess and report on all items under each treatment fidelity component in main outcomes articles. This reporting practice will likely enhance MBI interpretability and integrity. Instructions for use are threefold. First, we encourage researchers conducting MBI trials to use this tool in their development of a treatment fidelity plan to address each of the five BCC fidelity components (i.e., design, training, delivery, receipt, and enactment). Second, we encourage researchers to complete the checklist in the center column indicating the fidelity methods used in their study. Third, we encourage researchers to write additional descriptions of how they approached each point and provide corresponding data, when applicable, in the space within the far-right column. See Table 4 for a completed example based on protocol from Moment-by-Moment in Women’s Recovery (MMWR), a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a mindfulness-based relapse prevention program for racially/ethnically diverse women in residential treatment for substance use disorders (Amaro and Black 2017). Completing and including this checklist in main outcome papers will improve transparency of treatment fidelity methods and measures, which will provide critical information for the interpretation of MBI trial results.

Limitations and Future Research

Our interpretations are limited as we only included articles that described treatment fidelity methodology in a main outcomes paper. While 61 of 86 studies were excluded due to lack of description of treatment fidelity methodology, some of those may have assessed treatment fidelity but did not include it in the published paper(s) because of journal page limitations or author reporting style. Furthermore, we only included RCTs with the intent to focus on studies with the highest standard for internal validity; consequently, we omit quasi-experimental studies that may have reported on treatment fidelity. If we included quasi-experimental designs, we would expect more studies with lower reports of treatment fidelity compared to efficacy studies since treatment fidelity implementation requires extra staff time and costs in which experimental studies receive more resources to execute (Borrelli 2011). Finally, only the first author identified studies and abstracted data, which limits the replicability of our results due to human error (e.g., rater bias). However, the first author checked abstracted data multiple times and we aimed to critically review what has been published on MBI treatment fidelity versus systematically reviewing the literature. Therefore, we believe the quality and diversity of the programs reviewed allowed for a balanced representation of published articles and tool development.

Our Treatment Fidelity Tool for MBIs can address some of the evident limitations in the field. Ultimately, what is measured is equally as important as how it is measured (Breitenstein et al. 2010). Thus, our intent in developing this tool is to promote standardized and routine practice and report of treatment fidelity alongside future MBI outcomes. We believe our tool can be used by MBI investigators regardless of study design or study phase in order to develop, monitor, and evaluate treatment fidelity (Onken et al. 2014). In fact, we encourage the use of this tool across MBI studies with diverse designs, phases, and samples for the enhancement of understanding both treatment fidelity and participant outcomes. The use of common language and definitions in standardized reports will allow researchers to more accurately identify (1) treatment fidelity variation on MBI participant outcomes and (2) the specific mindfulness practices or program components that are efficacious, for whom, and why (Gould et al. 2016). Furthering our understanding of these mechanisms and using standardized protocol for MBI treatment fidelity may help prevent the science to service implementation cliff between efficacy to effectiveness studies (Onken et al. 2014). That is, by examining the level of treatment fidelity required to effectively deliver MBIs in research settings, we increase our ability to properly refine and feasibly disseminate MBIs in real-world settings.

References

Amaro, H., & Black, D. S. (2017). Moment-by-Moment in Women’s Recovery: randomized controlled trial protocol to test the efficacy of a mindfulness-based intervention on treatment retention and relapse prevention among women in residential treatment for substance use disorder. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 62, 146–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2017.09.004.

Barnhofer, T., Crane, C., Hargus, E., Amarasinghe, M., Winder, R., & Williams, J. M. (2009). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as a treatment for chronic depression: a preliminary study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(5), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.019.

Bellg, A. J., Borrelli, B., Resnick, B., Hecht, J., Minicucci, D. S., Ory, M., et al. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443.

Black, D. S. (2012). Mindfulness and substance use intervention. Substance Use & Misuse, 47(3), 199–201. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.635461.

Black, D. S. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions: an antidote to suffering in the context of substance use, misuse, and addiction. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(5), 487–491. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2014.860749.

Black, D. S., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12998.

Bondolfi, G., Jermann, F., der Linden, M. V., Gex-Fabry, M., Bizzini, L., Rouget, B. W., et al. (2010). Depression relapse prophylaxis with mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Replication and extension in the Swiss health care system. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(3), 224–231.

Borrelli, B. (2011). The assessment, monitoring, and enhancement of treatment fidelity in public health clinical trials. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 71.

Bowen, S., Chawla, N., Collins, S. E., Witkiewitz, K., Hsu, S., Grow, J., et al. (2009). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: A pilot efficacy trial. Substance Abuse, 30(4), 295–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/08897070903250084.

Bowen, S., Witkiewitz, K., Clifasefi, S. L., Grow, J., Chawla, N., Hsu, S. H., et al. (2014). Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546.

Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., Garvey, C. A., Hill, C., Fogg, L., & Resnick, B. (2010). Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(2), 164–173, https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20373.

Carmody, J. F., Crawford, S., Salmoirago-Blotcher, E., Leung, K., Churchill, L., & Olendzki, N. (2011). Mindfulness training for coping with hot flashes: results of a randomized trial. Menopause, 18(6), 611–620. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318204a05c.

Carroll, C., Patterson, M., Wood, S., Booth, A., Rick, J., & Balain, S. (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-2-40.

Cherkin, D. C., Sherman, K. J., Balderson, B. H., Cook, A. J., Anderson, M. L., Hawkes, R. J., et al. (2016). Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 315(12), 1240–1249.

Crane, R. S., Brewer, J., Feldman, C., Kabat-Zinn, J., Santorelli, S., Williams, J. M., et al. (2017). What defines mindfulness-based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003317.

de Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sørlie, T., et al. (2013). Mindfulness training for stress management: a randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Medical Education, 13(1).

Eisendrath, S., Gillung, E., Delucchi, K., Segal, Z., Nelson, J., McInnes, L., et al. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for treatment-resistant depression. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(2), 99–110.

Forgatch, M. S., Patterson, G. R., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2005). Evaluating fidelity: predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training. Behavior Therapy, 36(1), 3–13.

Garland, E. L., Thomas, E., & Howard, M. O. (2014). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement ameliorates the impact of pain on self-reported psychological and physical function among opioid-using chronic pain patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 48(6), 1091–1099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.03.006.

Garland, E. L., Roberts-Lewis, A., Tronnier, C. D., Graves, R., & Kelley, K. (2016). Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement versus CBT for co-occurring substance dependence, traumatic stress, and psychiatric disorders: proximal outcomes from a pragmatic randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.11.012.

Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., Huibers, M., van Os, J., & Wichers, M. (2012). Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in relation to prior history of depression: randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 201(4), 320.

Gould, L. F., Dariotis, J. K., Greenberg, M. T., & Mendelson, T. (2016). Assessing fidelity of implementation (FOI) for school-based mindfulness and yoga interventions: a systematic review. Mindfulness, 7(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0395-6.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., et al. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018.

Gross, C. R., Kreitzer, M. J., Thomas, W., Reilly-Spong, M., Cramer-Bornemann, M., Nyman, J. A., et al. (2010). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for solid organ transplant recipients: a randomized controlled trial. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 16(5), 30–38.

Hargus, E., Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., & Williams, J. M. G. (2010). Effects of mindfulness on meta-awareness and specificity of describing prodromal symptoms in suicidal depression. Emotion, 10(1), 34–42.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555.

Hoge, E. A., Bui, E., Marques, L., Metcalf, C. A., Morris, L. K., Robinaugh, D. J., et al. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(8), 786.

Hughes, J. W., Fresco, D. M., Myerscough, R., van Dulmen, M. H., Carlson, L. E., & Josephson, R. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction for prehypertension. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(8), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182a3e4e5.

JaKa, M. M., Haapala, J. L., Trapl, E. S., Kunin-Batson, A. S., Olson-Bullis, B. A., Heerman, W. J., et al. (2016). Reporting of treatment fidelity in behavioural paediatric obesity intervention trials: a systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 17(12), 1287–1300. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12464.

Jull, A., & Aye, P. S. (2015). Endorsement of the CONSORT guidelines, trial registration, and the quality of reporting randomised controlled trials in leading nursing journals: a cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(6), 1071–1079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.11.008.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156.

Kristeller, J. L., Wolever, R. Q., & Sheets, V. (2013). Mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) for binge eating: a randomized clinical trial. Mindfulness, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0179-1.

Kuyken, W., Hayes, R., Barrett, B., Byng, R., Dalgleish, T., Kessler, D., et al. (2015). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 386(9988), 63–73.

Leeuw, M., Goossens, M. E., de Vet, H. C., & Vlaeyen, J. W. (2009). The fidelity of treatment delivery can be assessed in treatment outcome studies: a successful illustration from behavioral medicine. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(1), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.03.008.

Lengacher, C. A., Shelton, M. M., Reich, R. R., Barta, M. K., Johnson-Mallard, V., Moscoso, M. S., et al. (2014). Mindfulness based stress reduction (MBSR(BC)) in breast cancer: evaluating fear of recurrence (FOR) as a mediator of psychological and physical symptoms in a randomized control trial (RCT). Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(2), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-012-9473-6.

Lichstein, K. L., Riedel, B. W., & Grieve, R. (1994). Fair tests of clinical trials: a treatment implementation model. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy, 16(1), 1–29.

Lloyd, A., White, R., Eames, C., & Crane, R. (2017). The utility of home-practice in mindfulness-based group interventions: a systematic review. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0813-z.

McManus, F., Surawy, C., Muse, K., Vazquez-Montes, M., & Williams, J. M. G. (2012). A randomized clinical trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus unrestricted services for health anxiety (hypochondriasis). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(5), 817.

Moynihan, J. A., Chapman, B. P., Klorman, R., Krasner, M. S., Duberstein, P. R., Brown, K. W., et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for older adults: effects on executive function, frontal alpha asymmetry and immune function. Neuropsychobiology, 68(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1159/000350949.

NIH (2012). NIH Policies and Procedures for Promoting Scientific Integrity. https://www.nih.gov/sites/default/files/about-nih/nih-director/testimonies/nih-policies-procedures-promoting-scientific-integrity-2012.pdf. Accessed October 2017.

Onken, L. S., Carroll, K. M., Shoham, V., Cuthbert, B. N., & Riddle, M. (2014). Reenvisioning clinical science: unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(1), 22–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613497932.

O'Reilly, G. A., Cook, L., Spruijt-Metz, D., & Black, D. S. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions for obesity-related eating behaviours: a literature review. Obesity Reviews, 15(6), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12156.

Palta, P., Page, G., Piferi, R. L., Gill, J. M., Hayat, M. J., Connolly, A. B., et al. (2012). Evaluation of a mindfulness-based intervention program to decrease blood pressure in low-income African-American older adults. Journal of Urban Health, 89(2), 308–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-011-9654-6.

Resnick, B., Bellg, A. J., Borrelli, B., Defrancesco, C., Breger, R., Hecht, J., et al. (2005). Examples of implementation and evaluation of treatment fidelity in the BCC studies: where we are and where we need to go. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 29(Suppl), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_8.

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., & Group, C. (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMC Medicine, 8, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-8-18.

Segal Z. V., Williams J. M. G., & Teasdale J. D. (2002). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Segal, Z. V., Bieling, P., Young, T., MacQueen, G., Cooke, R., Martin, L., et al. (2010). Antidepressant monotherapy vs sequential pharmacotherapy and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or placebo, for relapse prophylaxis in recurrent depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(12), 1256–1264. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.168.

Shallcross, A. J., Gross, J. J., Visvanathan, P. D., Kumar, N., Palfrey, A., Ford, B. Q., et al. (2015). Relapse prevention in major depressive disorder: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy versus an active control condition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(5), 964–975. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000050.

van der Velden, A. M., Kuyken, W., Wattar, U., Crane, C., Pallesen, K. J., Dahlgaard, J., et al. (2015). A systematic review of mechanisms of change in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the treatment of recurrent major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 26–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.001.

van Son, J., Nyklicek, I., Pop, V. J., Blonk, M. C., Erdtsieck, R. J., Spooren, P. F., et al. (2013). The effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on emotional distress, quality of life, and HbA(1c) in outpatients with diabetes (DiaMind): a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care, 36(4), 823–830. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-1477.

Williams, J. M., Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., Brennan, K., Duggan, D. S., Fennell, M. J., et al. (2014). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for preventing relapse in recurrent depression: a randomized dismantling trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(2), 275–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035036.

Zgierska, A. E., Shapiro, J., Burzinski, C. A., Lerner, F., & Goodman-Strenski, V. (2017). Maintaining treatment fidelity of mindfulness-based relapse prevention intervention for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial experience. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2017, 9716586. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9716586.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Adam M. Leventhal for his support and constructive comments on manuscript conceptualization and development.

Funding

Funding support provided by (1) the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA038648 to H.A. and D.B.) and co-sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and (2) a National Cancer Institute training grant (T32CA009492-33 to A.K.). These funding agencies had no role in the design or execution of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.: study conceptualization, methodology, literature search, data extraction, and lead of manuscript writing. H.A.: study conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, manuscript writing and D.B.: study conceptualization, methodology, funding acquisition, manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kechter, A., Amaro, H. & Black, D.S. Reporting of Treatment Fidelity in Mindfulness-Based Intervention Trials: A Review and New Tool Using NIH Behavior Change Consortium Guidelines. Mindfulness 10, 215–233 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0974-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0974-4