Abstract

Attachment-based compassion therapy (ABCT) is a new protocol of compassion based on attachment theory. The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of this protocol for improving self-compassion in a healthy population and determine whether improvements in self-compassion mediate changes towards a more secure attachment style. The study consisted of a non-randomized controlled trial with an intervention group (ABCT) and a waiting list control group. In addition to pre- and post-intervention assessments, a 6-month follow-up assessment was included. Participants were healthy adults attending ABCT courses who self-rated as not having any psychological disorders and self-reported as not receiving any form of psychiatric treatment. Compared to the control condition, ABCT was significantly more effective for improving self-compassion as evidenced by changes on all subscales on the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS), except isolation. Effect sizes were in the moderate to large range and correlated with the number of sessions received. ABCT also led to improvements across all subscales of the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), except describing. ABCT decreased psychological disturbance assessed using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) and decreased experiential avoidance assessed using the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II). Furthermore, ABCT led to significant reductions in levels of anxiety and avoidance. Secure attachment style significantly increased in the ABCT group and was mediated by changes in self-compassion. In summary, ABCT may be an effective intervention for improving self-compassion and attachment style in healthy adults in the general populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Compassion has been defined as a multicomponent construct that includes (1) an awareness of suffering (cognitive/attentional component), (2) a sympathetic concern related to being emotionally moved by suffering (affective component), (3) a wish to see the relief of that suffering (intentional component) and (4) a responsiveness or readiness to help relieve that suffering (motivational component) (Jinpa 2010). Compassion has been a focus of research in recent years and is associated with positive emotions (Fredrickson et al. 2008) as well as improved response to psychosocial stress (Pace et al. 2009). Furthermore, randomized control trials (RCTs) indicate that compassion-based interventions are effective treatments for (among other conditions) psychosis, binge-eating disorder, depression, anxiety and diabetes (Shonin et al. 2017). These findings are supported by systematic reviews and meta-analyses, indicating that compassion has an important role to play in the treatment of depression and anxiety (Galante et al. 2014; Leaviss and Uttley 2015; Macbeth and Gumley 2012; Shonin et al. 2015).

The following four intervention protocols are principally based on compassion: (i) Cognitively based Compassion Training (CBCT; Pace et al. 2009) that has been shown to reduce levels of immune and behavioral stress-induced biomarkers (e.g. blood plasma levels of interleucine-6); (ii) Compassion Cultivating Training (CCT; Jazaieri et al. 2015) that has been shown to improve levels of compassion, mindfulness, positive affect and mental wandering (Jazaieri et al. 2013; Jazaieri et al. 2014; Jazaieri et al. 2015); (iii) Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT; Gilbert 2014) that has applications for treating psychiatric disorders where there are elements of self-criticism, shame and/or rumination (Leaviss and Uttley 2015); and (iv) Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC; Neff 2012) that has been shown to improve levels of self-compassion, mindfulness and subjective well-being (Neff and Germer 2013).

These protocols on compassion are tailored to fit with the health systems and cultural nuances of English-speaking countries. Furthermore, Gilbert’s CFT is arguably the only approach that can be truly be deemed to be a clinical intervention. Consequently, a new protocol of compassion, called attachment-based compassion therapy (ABCT; Garcia-Campayo and Demarzo 2015; García-Campayo et al., 2016a, b), was developed to adapt better to the cultural and health system requirements of Latin countries (Demarzo et al. 2015; García-Campayo et al. 2017). ABCT is different from previous approaches because it is based on attachment theory and thus includes practices to raise awareness and/or address maladaptive aspects of attachment styles developed with parents.

ABCT consists of eight sessions, each of which is 2.5 h in duration and, in addition to mindfulness techniques, it includes compassion practices such as receiving and giving compassion to onself, friends, unknown people, and people deemed to be problematic. The protocol is intended not only for improving psychological well-being in healthy individuals but also for treating psychiatric disorders, such as depression and fibromyalgia, for which it has demonstrable efficacy (Montero-Marin et al. 2018). ABCT also includes practices to help the participant identify their own attachment style and understand how it influences their current interpersonal relationships. According to attachment theory, the type of relationships established in adulthood closely follows the relationship model developed with parents during childhood (Fearon and Roisman 2017). ABCT seeks to raise awareness of the attachment style developed with parental figures and, where appropriate, to address maladaptive aspects of this fundamental attachment relationship. In essence, this process is taught as a form of both compassion and self-compassion in order to improve present-day interpersonal relationships and well-being more generally. This is in line with findings demonstrating that there are a range of health benefits associated with compassion and self-compassion practices (Shonin et al. 2017).

Cross-sectional studies show that individuals with secure attachment as a trait report higher mindfulness levels than those with insecure attachment (Goodall et al. 2012). The most definitive study on the relationship between attachment and mindfulness (Pepping et al. 2014) demonstrated that mindfulness and secure attachment are more strongly related in meditators compared to non-meditators. Based on these findings, it is reasonable to assume that the use of mindfulness and compassion practices will facilitate the development of a secure attachment style.

The aim of the present study was to assess the efficacy of ABCT for improving levels of self-compassion and attachment style in a healthy adult population. It is hypothesized that compared to a waiting list control group (CG), participants in the ABCT group will demonstrate increased levels of mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological well-being and thus modify their attachment style. It is also hypothesized that self-compassion may exert a mediating role in modifying attachment towards a more secure style.

Method

Participants

ABCT participants were healthy male and female adults attending ABCT courses linked to the Master of Mindfulness programme at the University of Zaragoza (Spain). The control group was recruited from acquaintances and relatives of the participants in the intervention group. The inclusion criteria for both the intervention and control groups were as follows: (a) self-rating as not having a psychological disorder and not receiving any psychiatric treatment, (b) can speak and write using the Spanish language, (c) aged between 18 and 65 years and (d) provided informed consent. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) self-rating as having a mental disorder or currently receiving pharmacological treatment for a psychological disorder, (b) < 18 years of age or > 65 years of age and (c) unavailiable to receive ABCT or refusing/failing to sign the informed consent form.

Based on a meta-analysis, the average effect size observed in healthy populations after receiving compassion or loving-kindness training is d = 0.6 (Galante et al. 2014). Consequently, in the current study, the sample size was estimated based on a moderate standardized difference between groups of d = 0.6 (i.e. focussing on the main outcome of self-compassion). Assuming a common standard deviation, a 5% significance level and a statistical power of 80%, approximately 45 participants were required for each group (i.e. 90 participants in total) in order to detect this difference. Attrition rates were not considered because participants had to pay for the intervention, and it was thus presumed they were highly motivated (Fiorini 2006).

The flow of participants through the study is presented in Fig. 1. Of the 57 individuals that requested to receive the ABCT training, nine (15.8%) were taking psychiatric pharmacological medication, one was older than 65 years (1.8%) and two (3.5%) were unwilling to sign the informed consent form. Accordingly, 45 individuals (78.9%) met the study criteria and were invited to participate. Of the 51 control group participants that expressed an interest in joining the study, three were taking psychiatric pharmacological medication (5.9%), and three (5.9%) did not sign the informed consent form. At post-treatment, one member of each group had withdrawn, and at 6-month follow-up, one participant from the intervention group and two from the control group had withdrawn. Thus, the final sample evaluated at 6-month follow-up comprised 43 participants from the intervention group and 42 from the control group (dropout = 5.6%).

Procedure

The present study employed a non-randomized controlled trial design with an intervention group (ABCT) and a waiting-list control group. Pre-post tests were administered and a 6-month follow-up assessment was conducted.

Since 2014, the Master of Mindfulness programme at the University of Zaragoza has offered courses on compassion every 2 months. The courses are advertised on the internet. For the general population, courses are described as contributing to increased psychological well-being but not for treating a pathology. Although the current study did not employ a formal clinician interview to screen out participants with mental disorders, prior to completing the survey, all participants were asked two questions by the interviewer; one related to whether they had a current mental disorder and the other to whether they were taking any psychiatric medication. To assess the protocol under similar terms to those applied during normal conditions, participants had to pay 170 € to cover the cost of the course and accompanying manual (Garcia Campayo and Demarzo 2015). Control group participants were recruited from family members or acquaintances of the intervention group participants. The reason for this was to maximize homogeneity between the two groups given that relatives came from the same living environment. All participants provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Aragon. Participants were considered to have fulfilled the requirements of the course upon attending a minimum of six of the eight weekly sessions (75%).

Intervention

The intervention group attended ABCT training, which consisted of eight 2-h sessions (one session per week) that included specific mindfulness practices and self-compassion visualizations, and involved helping participants understand the attachment style that was generated in childhood. The programme included daily homework assignments that took 15 to 20 min to complete. The therapist facilitating this group (MNG) was a psychologist specifically trained to conduct ABCT teacher training. The outline of the content of the eight sessions is as follows:

Session 1: Theoretical foundations of compassion. Brain evolution, happiness and suffering. Concept of compassion and elimination of mistaken beliefs.

Session 2: Deepening self-esteem and compassion. Mindfulness and compassion. Differences in self-esteem and how to manage and cope with the fear of compassion.

Session 3. Developing my compassionate world. Mechanisms by which compassion is activated. Importance of replacing self-criticism with self-compassion.

Session 4. Relationships and compassion. Parenting models during childhood. How relationships with parents generate different ways of relating to the world.

Session 5. Working on ourselves. Reconstruction of a secure attachment model, modifying the relationships with self and others through compassion.

Session 6. Advanced compassion. Forgiveness and common barriers to its development. The importance of forgiveness towards oneself and others.

Session 7. Advanced compassion. Envy and the importance of developing an attachment figure based on oneself. How to manage difficult relationships.

Session 8. Transmitting compassion towards others. Equanimity as an outcome of compassion practice. How to maintain compassion during everyday life.

Weekly sessions start with a short compassion meditation practice. Basic theoretical concepts are subsequently introduced and combined with practices intended to foster compassion and raise awareness of attachment style. For example, session 1 includes the following: (a) theory covering how the brain works, pain and suffering and what is and is not compassion and (b) meditation practices involving breathing and compassionate body scan, compassionate awareness of intrapsychic difficulties and arduous circumstances and appreciating positive events of the day. All weekly practices are available for participants to practice at home (i.e. between weekly sessions).

Twenty-five percent of the ABCT intervention sessions were randomly audio-recorded, and another researcher (JGC) monitored the recorded sessions using a checklist to confirm that the therapist did not deviate from the manualized protocol (García-Campayo and Demarzo 2015).

Measures

Participants completed a socio-demographic and clinical survey based on a paper-and-pencil battery of questionnaires. Assessment measures were administered pre-intervention, post-intervention and 6 months after completing the course. The following socio-demographic information was collected: gender, age, relationship status (i.e. in a stable relationship, not in a stable relationship), education level (i.e. primary, secondary, university) and employment status (i.e. unemployed, employed, sick leave/disability, retired).

Self-Compassion Scale (Neff 2003)

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) is a 26-item measure rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The SCS measures the following six facets of compassionate and uncompassionate behaviours towards self (omega values of composite reliability in the present study sample are in brackets): self-kindness (ω = 0.83), self-judgement (ω = 0.81), common humanity (ω = 0.69), isolation (ω = 0.89), mindfulness (ω = 0.76) and over-identification (ω = 0.79). The SCS can be used as a single measure of self-compassion by summing the six facets after reversing negative facets. It has demonstrated strong convergent and discriminant validity, good test–retest reliability and internal consistency (Neff 2003; Neff et al. 2007). We used the Spanish-validated version of this scale (Garcia-Campayo et al. 2014).

Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (Baer et al. 2006; Cebolla et al. 2012)

The mindfulness trait was evaluated using the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) which consists of 39 items rated on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). These items measure a personal disposition towards being mindful in daily life by focusing on five facets of mindfulness. These include (omega values of reliability in the study sample are in brackets) observing (ω = 0.77), which is the capacity to pay attention to internal and external experiences such as sensations, thoughts, and emotions; describing (ω = 0.93), which is the ability to describe events and personal responses using words; acting with awareness (ω = 0.86), which is the ability to focus on the activity being carried out as opposed to behaving automatically; non-judging of inner experience (ω = 0.90), which is the ability to take a non-evaluative stance towards thoughts and feelings; and non-reactivity to inner experience (ω = 0.78), which is the ability to allow thoughts and feelings to come and go without getting caught up in, or carried away by, them (Baer et al. 2008).

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (Bond et al. 2011)

This assessment tool measures experiential avoidance which it contexualizes as the unwillingness to experience unwanted emotions, thoughts and/or distressing psychological events. The dominance of private experiences over chosen values and contingencies in guiding a behaviour or action is the core of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) model of psychopathology (Hayes et al. 1999). The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) consists of seven items, and the responses are recorded on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (never) to 7 (always). Higher scores indicate greater experiential avoidance (EA). The Spanish version of the AAQ-II, which has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of EA, was employed in the current study (Ruiz et al. 2013). Composite reliability in the present study sample was ω = 0.94.

General Health Questionnaire (Bridges and Goldberg 1986)

This is a 28-item self-report Likert-scale tool that assesses psychosocial distress in the general population. It has four subscales, namely, (i) somatic symptoms, (ii) anxiety/insomnia, (iii) social dysfunction and (iv) severe depression. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) can be used as a single measure of psychosocial distress (omega value of composite reliability in the present study sample was ω = 0.72). The Spanish-validated version of the questionnaire was used in the current study (Lobo et al. 1988).

Relationship Questionnaire (Bartholomew and Horowitz 1991)

The Relationship Questionnaire (RQ) uses a 7-point Likert-scale that assesses and matches participants with one of four attachment styles: (i) secure, (ii) pre-occupied, (iii) dismissive and (iv) fearful. A mathematical calculation permits a categorical assessment of attachment style (i.e. secure or insecure) (Griffin and Bartholomew 1994a), and qualitative self-descriptor criteria can be used for confirmatory purposes. Studies have demonstrated that the reliability of the self-descriptor criteria is high (Leak and Parsons 2001; Yarnoz-Yaben and Comino 2011). The RQ also offers the possibility of measuring two key dimensions underlying attachment in adults (Griffin and Bartholomew 1994a)—namely, anxiety, which relates more to the self, and avoidance, which relates more to others (Griffin and Bartholomew 1994b). The anxiety dimension is calculated using the sum of the four attachment style ratings. High scores in this dimension reflect high anxiety towards social relationships (i.e. pre-occupied and fearful), whereas low scores reflect low anxiety towards relationships (i.e. secure and dismissive). Avoidance scores are obtained by summing the scores for high dismissive and fearful attachment styles and ignoring those for secure and pre-occupied attachment styles). In the current study, the Spanish-validated version of the questionnaire was used as it shows adequate psychometric properties (Alonso-Arbiol 2000).

Data Analyses

Descriptive data (i.e. means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were compared to assess the balance of socio-demographic and psychological variables between groups at baseline. The primary between-group analysis to assess intervention effects was performed on an intention-to-treat basis (White et al. 2011) using the six SCS subscales as continuous variables. Linear mixed-effects models were employed, and the correlation between the repeated measures for each individual was accounted for using restricted maximum likelihood regression (REML) because REML produces less biased estimates of variance parameters when using small sample sizes or unbalanced data (Egbewale et al. 2014). Regression coefficients (Bs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for the ‘group × time’ interactions at post-test and at 6-month follow-up. The effect size (ES) estimates for each pairwise comparison used the dppc2 (Carlson and Schmidt 1999), and the pooled pre-test SD was used to weight the differences in the pre-post means and to correct for the population estimate (Morris 2008). As a rule, an effect size of 0.20 is considered small, 0.50 medium and 0.80 large.

Separate models were estimated for each of the continuous secondary outcomes using the same analytical procedure. We also compared the percentage of each attachment style (categorical variable) at any time point using the Fisher exact probability test. Furthermore, we examined whether the ABCT condition was associated with higher SCS pre-post differential scores than the control condition. At this stage, the SCS was considered a unidimensional score to keep the statistical analyses as parsimonious as possible. The conditions were compared using the t test for independent groups. We also examined whether the number of sessions completed was correlated with SCS pre-post differential scores using the Spearman R coefficient. Moreover, using the corresponding t test, we evaluated whether participants with an insecure attachment style at pre-test who moved to a secure style at follow-up recorded higher pre-post differential scores on the SCS than those who remained in any of the insecure attachment styles.

Finally, we examined whether the effect of ABCT on moving from an insecure attachment style at baseline to a secure attachment style at 6-month follow-up was mediated through changes in the SCS at post-test. For this, we explored the direct and indirect relationships among group condition, SCS change scores, and change from an insecure to secure attachment style using path analysis, where (i) the treatment condition was the independent variable, (ii) the SCS pre-post change score was the mediator and (iii) change in attachment style moving from an insecure attachment style at baseline to a secure attachment style at 6-month follow-up was the dependent variable. The abovementioned algorithm based on the RQ was used to calculate secure and insecure attachment styles (Griffin and Bartholomew 1994a), considering change as a dichotomous variable in which 0 = ‘no shift from insecure to secure attachment style’ and 1 = ‘shift from insecure to secure attachment style’ (thus, only participants with an insecure attachment style at baseline were included in the analysis). A simple mediation analysis was conducted to test the indirect effect path between treatment condition and attachment style at follow-up through the SCS pre–post change, using maximum likelihood-based path analysis for dichotomous dependent variables, with unstandardized path estimates from logistic regression coefficients.

The regression coefficient of bootstrapped indirect effects was calculated as was its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). This procedure produces a test that can be applied to small samples to overcome possible problems of asymmetry in the distribution of the indirect effects (Lockhart et al. 2011). Indirect effects were considered statistically significant when the 95% CI of the corresponding B parameter did not include zero.

The overall α level was set at 0.05 using two-sided tests, and Bonferroni’s criterion was considered to balance between type I and type II errors. Therefore, the final critical level for the primary analyses was 0.008 due to the use of the six SCS facets as primary outcome measures. Because the secondary analyses were considered exploratory, no corrections for multiple measurements were applied (Feise 2002). Analyses were performed using the STATA-12 and SPSS-19 statistical packages.

Results

Participants were predominantly female (n = 80; 88.9%) and had a mean age of 50.74 years (SD = 7.89) with a range of 34 to 68 years. The majority of participants were employed (n = 64; 71.1%) and in stable relationships (n = 62; 68.9%). All participants had university education and were of European ethnicity. There were no apparent differences between the ABCT and control group with respect to other socio-demographic variables (Table 1). Baseline psychological characteristics of the sample (i.e. compassion measured with SCS, mindfulness measured with FFMQ, experiential avoidance measured with AAQ-II, and psychological distress measured with GHQ-28) were in the expected normal ranges (Table 1). Regarding attachment styles, the self-described model was secure for 44 participants (48.9%), and the remaining participants (n = 46; 51.1%) were distributed among pre-occupied (n = 23; 25.6%), dismissive (n = 19; 21.1%) and fearful (n = 4; 4.4%), with no differences between the two treatment conditions (Fisher exact probability test p value = 0.736). Anxiety and attachment avoidance also revealed similar scores between groups (Table 1). All participants in the treatment group participated in at least six sessions, with a mean of 7.76 sessions (SD = 0.52), a median of 8 and a mode of 8. Specifically, two participants (4.4%) completed six sessions, seven participants (15.6%) completed seven sessions and 36 participants (80%) completed all eight sessions.

As shown in Table 2, there were high ESs and significant differences at post-treatment and at 6-month follow-up in all subscales of the SCS, except isolation, which showed a moderate ES and a trend due to correction by multiple comparisons (post-test B = 1.05; d = − 0.49; p = 0.010; follow-up B = 0.91; d = − 0.42; p = 0.027), thus confirming the effect of the intervention on self-compassion rates.

With respect to the secondary outcomes (Table 3), significant improvements were observed at post-treatment and at follow-up for all FFMQ measures of mindfulness, except describing (post-test B = − 0.84; d = 0.22; p = 0.409; follow-up B = − 0.56; d = 0.18; p = 0.585). There were also significant decreases on the AAQ-II and the GHQ-28 as well as decreases on the measures of anxiety and of attachment avoidance (Table 3). While the distribution of attachment styles revealed no difference between groups at pre-test (Fisher p = 0.736), significant differences were found at post-test (Fisher p = 0.004) and at follow-up (Fisher p = 0.003), with clear increments in the secure attachment category at both time points in the ABCT group compared with the pre-treatment results (Table 4).

The ABCT treatment condition exhibited significantly higher pre-post differential scores on the self-compassion total score than did the control group [ABCT mean = 27.52 (SD = 5.47); control mean = 1.84 (SD = 4.26); p < 0.001]. The number of sessions attended was also significantly correlated with the pre-post differential scores on the self-compassion total score (R = 0.84; p < 0.001). Moreover, when considering only participants with an insecure attachment style at pre-test (n = 44), those that moved to a secure attachment style at follow-up showed significantly higher pre-post differential scores on the self-compassion total compared to those who remained in any of the insecure attachment styles [secure attachment (n = 10) mean = 31.10 (SD = 5.24); insecure attachment (n = 34) mean = 10.62 (SD = 12.35); p < 0.001].

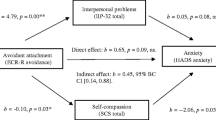

A mediation analysis was conducted using maximum likelihood-based path analysis for dichotomous dependent variables. It was observed that the treatment condition indirectly influenced the change in moving from an insecure attachment style at pre-test to a secure attachment style at follow-up through its effects on total self-compassion pre-post differential scores (Fig. 2). Participants in the treatment condition exhibited higher improvements in self-compassion versus controls (a = 25.82; p < 0.001), and this improvement in self-compassion predicted the change in moving from an insecure to a secure attachment style (b = 0.21; p = 0.044). A bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect (ab = 5.35) based on 10,000 bootstrap samples was entirely above zero (95% CI = 0.23–12.25). There was no evidence that group location influenced the change in moving from an insecure attachment style to a secure attachment style independent of its effect on self-compassion (c′ = 17.96; p = 0.999).

Mediation model on the association of the treatment condition with the change in moving from any unsafe attachment style to a secure attachment style by self-compassion (n = 44). Notes: *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. Path coefficients are unstandardized maximum likelihood-based logistic regression coefficients (a × b = indirect effects; and c′ = direct effects adjusted by the mediating effect)

Discussion

Attachment-based compassion therapy (ABCT) is a recently developed model of compassion treatment that emphasizes the importance of attachment styles (Garcia-Campayo and Demarzo 2015; García-Campayo et al., 2016a, b). Previous studies have already suggested the efficacy of this model for the treatment of fibromyalgia (Montero-Marin et al. 2018). The present study recruited healthy adults from the general population and evaluated the effects of ABCT on self-compassion, mindfulness, experiential avoidance, psychological distress and anxiety and avoidance related to attachment style.

Findings demonstrated that compared to a waiting list control group, ABCT was effective in improving self-compassion (i.e. the main outcome of the present study) as shown by significant imporvements in the majority of the six SCS subscales, each demostrating moderate to large ESs. Furthermore, the ES of ABCT for improving self-compassion was higher than the mean reported in a previous meta-analysis on the efficacy of compassion (Galante et al. 2014). Therefore, it appears that ABCT may be an effective intervention for increasing levels of compassion in adults of healthy clinical status. ABCT also improved other important psychological variables in this population including mindfulness (increases were observed across all subscales of the FFMQ, except describing). This is in line with outcomes from previous studies that have demonstrated that loving-kindness and compassion meditation can increase levels of mindfulness in patients with personality disorders (Feliu et al. 2017). However, although a meta-analysis demonstrated that compassion therapy led to moderate increases in mindfulness compared to a passive control condition, findings were inconclusive when the increases in mindfulness were compared with an active control condition (Galante et al. 2014). This was further confirmed in studies in which an intervention unrelated to mindfulness—known as the Health Enhancement Programme—increased mindfulness (when measured using the FFMQ) at the same level as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (Goldberg et al. 2016). Thus, it cannot be ruled out that increases in mindfulness produced by ABCT in the present study reflect an unspecified effect.

ABCT decreased psychological disturbance as measured by the GHQ-28, one of the most widely used questionnaires for the screening of psychiatric problems in the general population. Compassion has been shown to be effective for the treatment of depression, anxiety and pain (Chapin et al. 2014; Galante et al. 2014), three of the conditions assessed by three of the four GHQ-28 components. Therefore, the abovementioned reduction in psychological disturbance observed in the present study is in line with outcomes from other compassion intervention studies. Consitent with the reductions in EA also observed in the present study, some studies have demonstrated that training in loving-kindness and compassion meditation can increase acceptance (a concept closely related with EA) in patients with personality disorders (Feliu et al. 2017). Furthermore, self-compassion training has been shown to reduce the avoidance of difficult thoughts and feelings following a stressful event (Neff and Germer 2013).

A previous Spanish general population study using the RQ found a prevalence of secure attachment that exceeded that observed in our sample (Yarnoz-Yaben and Comino 2011). This was also the case in a study involving married (or living as a couple) persons in the USA (Mickelson et al. 1997) as well as among a sample of married couples in Germany (Banse 2004). However, the prevalence of secure attachment in samples of divorced people in Spain (Yarnoz-Yaben 2010) was similar to that observed in the present study, although two thirds of participants in this the present study were in a stable relationship. Other studies of the general Spanish population (Yarnoz-Yaben et al. 2001) and of Spanish students (Alonso-Arbiol 2000) have reported prevalence rates similar to those observed in the present study. Likewise, anxiety and avoidance levels related to attachment baseline levels found in the present study population were similar to the ranges reported in previous studies of the Spanish general population (Yarnoz-Yaben and Comino 2011).

To the present authors’ knowledge, there are no previous studies investigating the effect of compassion therapy on attachment style, although a pilot study has been conducted that used a mindfulness intervention and found no effects on attachment style (Pepping et al. 2015). In the present study, it was found that ABCT decreased levels of anxiety and avoidance relating to attachment at both post-test and 6-month follow-up. Moreover, secure attachment significantly increased at post-treatment and at 6-month follow-up, principally in the form of improvements in pre-occupied and dismissive attachment but with no improvements in fearful attachment. Gains in self-compassion at post-test as a result of the intervention were found to mediate the change towards moving from an insecure to a secure style at follow-up. Several studies have described the relationship between self-compassion and attachment. For example, fear of compassion is correlated with alexithymia, depression, anxiety and stress (Gilbert et al. 2014). Furthermore, self-compassion appears to play a central role in explaining the associations between attachment anxiety and body appreciation (Raque-Bogdan et al. 2016). Accordingly, compassion has been used as a therapy in patients with insecure attachment (Krasuska et al. 2017).

Limitations

The main limitation of the present study is that it was not a randomized study. Consequently, it is not possible to rule out biases that would be eliminated by randomization. In addition, some of the questionnaires used in the study (e.g. the SCS), present inconsistencies in terms of factorial structure (Montero-Marin et al. 2016). Furthermore, given that the control group were not enrolled on the Masters in Mindfulness programme and were recruited from acquaintances and family members of the ABCT group, it could be that the two groups were not matched in terms of levels of motivation, and there could also have been an element of ‘cross-talk’ between groups. However, losses during the treatment and follow-up were minimal and were similar between both groups, which indicate that the same participant characteristics present in the beginning of the study were present at the end. The main strengths of this study were that it was controlled, the sample was sufficiently large, there was a follow-up assessment at 6 months post-intervention, the intervention followed the manualized protocol and the evaluation of adherence to protocol was conducted by a researcher other than the therapist. Furthermore, because during the recruitment process the percentage of participants ruled out due to inclusion criteria was low, biases during selection can be considered minimal.

In summary, despite the aforementioned limitations, findings from the present study indicate that ABCT may be an effective intervention for (i) increasing self-compassion in healthy adult populations and (ii) decreasing psychological disturbance by increasing dimensions of mindfulness and diminishing EA. Furthermore, due to the structure of the intervention—which is grounded in attachment theory—ABCT appears to improve two key dimensions of attachment (i.e. anxiety and avoidance) and to modify attachment styles towards a secure model by improving self-compassion. Nevertheless, it is recommended that future RCTs are conducted to confirm these results.

References

Alonso-Arbiol, I. (2000). Atxkimendu insegurua eta genero rolak pertsonarteko mendekotasunaren korrelatu gisa. Doctoral Dissertation. Basque Country University. Sebastián.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27–45.

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., et al. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and non meditating samples. Assessment, 15, 329–342.

Banse, R. (2004). Adult attachment and marital satisfaction: evidence for dyadic configuration effects. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(2), 273–282.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226–244.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behaviour Therapy, 42(4), 676–688.

Bridges, K. W., & Goldberg, D. P. (1986). The validation of the GHQ-28 and the use of the MMSE in neurological in-patients. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 148(5), 548–553.

Carlson, K. D., & Schmidt, F. L. (1999). Impact of experimental design on effect size: Findings from the research literature on training. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(6), 851–862.

Cebolla, A., García-Palacios, A., Soler, J., Guillen, V., Baños, R., & Botella, C. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Spanish validation of the five facets of mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ). The European Journal of Psychiatry, 26(2), 118–126.

Chapin, H. L., Darnall, B. D., Seppala, E. M., Doty, J. R., Hah, J. M., & Mackey, S. C. (2014). Pilot study of a compassion meditation intervention in chronic pain. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 1(1), 4.

Demarzo, M. M., Cebolla, A., & García-Campayo, J. (2015). The implementation of mindfulness in healthcare systems: a theoretical analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 37(2), 166–171.

Egbewale, B. E., Lewis, M., & Sim, J. (2014). Bias, precision and statistical power of analysis of covariance in the analysis of randomized trials with baseline imbalance: a simulation study. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 49.

Fearon, R. M. P., & Roisman, G. I. (2017). Attachment theory: progress and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 131–136.

Feise, R. J. (2002). Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2(1), 8.

Feliu-Soler, A., Pascual, J. C., Elices, M., Martín-Blanco, A., Carmona, C., Cebolla, A., et al. (2017). Fostering self-compassion and loving-kindness in patients with borderline personality disorder: a randomized pilot study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24(1), 278–286.

Fiorini, H.J. (2006). Theory and technique of psychotherapy. Buenos Aires: Nueva Visión.

Fredrickson, B. L., Cohn, M., Coffey, K. A., Pek, J., & Finkel, S. A. (2008). Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1045–1062.

Galante, J., Galante, I., Bekkers, M. J., & Gallacher, J. (2014). Effect of kindness-based meditation on health and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1101.

García-Campayo, J., & Demarzo, M. (2015). Mindfulness y compasión: la nueva revolución. Barcelona: Siglantana.

Garcia-Campayo, J., Navarro-Gil, M., Andrés, E., Montero-Marin, J., López-Artal, L., & Demarzo, M. M. P. (2014). Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12(1), 4.

García-Campayo, J., Cebolla, A., & Demarzo, M. M. (2016a). La ciencia de la compasión: más allá del mindfulness. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

García-Campayo, J., Navarro-Gil, M., & Demarzo, M. (2016b). Attachment-based compassion therapy. Mindfulness & Compassion, (2), 68–74.

García-Campayo, J., Demarzo, M., Shonin, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2017). How do cultural factors influence the teaching and practice of mindfulness and compassion in Latin countries? Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1161.

Gilbert, P. (2014). The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(1), 6–41.

Gilbert, P., McEwan, K., Catarino, F., Baião, R., & Palmeira, L. (2014). Fears of happiness and compassion in relationship with depression, alexithymia, and attachment security in a depressed sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53, 228–244.

Goldberg, S. B., Wielgosz, J., Dahl, C., Schuyler, B., MacCoon, D. S., Rosenkranz, M., et al. (2016). Does the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire measure what we think it does? Construct validity evidence from an active controlled randomized clinical trial. Psychological Assessment, 28(8), 1009.

Goodall, K., Trejnowska, A., & Darling, S. (2012). The relationship between dispositional mindfulness, attachment security and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 622–626.

Griffin, D. W., & Bartholomew, K. (1994a). The metaphysics of measurement: the case of adult attachment. In K. Bartholomew y D. Perlman (Eds.), Advances in personal relationships (Vol. 5: Adult attachment relationships, pp. 17-52). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Griffin, D. W., & Bartholomew, K. (1994b). Models of the self and other: Fundamental dimensions underlying measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(3), 430–445.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy. An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford.

Jazaieri, H., Jinpa, G. T., McGonigal, K., Rosenberg, E. L., Finkelstein, J., Simon- Thomas, E., & Goldin, P. R. (2013). Enhancing compassion: a randomized controlled trial of a compassion cultivation training program. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1113–1126.

Jazaieri, H., McGonigal, K. M., Jinpa, T. L., Doty, J. R., Gross, J. J., & Goldin, P. R. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of compassion cultivation training: effects on mindfulness, affect, and emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion, 38, 23–35.

Jazaieri, H., Lee, I. A., McGonigal, K., Jinpa, T., Doty, T., Gross, J. R., & Golding, P. R. (2015). A wandering mind is a less caring mind: daily experience sampling during compassion meditation training. The Journal of Positive Psychology, (1, 1), 37–50.

Jinpa, G. T. (2010). Compassion cultivation training (CCT): instructor’s manual (unpublished).

Krasuska, M., Millings, A., Lavda, A. C., & Thompson, A. R. (2017). Compassion focussed self-help for skin conditions in individuals with insecure attachment: a pilot evaluation of the acceptability and potential effectiveness. British Journal of Dermatology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.15934

Leak, G. K., & Parsons, C. J. (2001). The susceptibility of three attachment style measures to socially desirable responding. Social Behavior and Personality, 29, 21–30.

Leaviss, J., & Uttley, L. (2015). Psychotherapeutic benefits of compassion-focused therapy: an early systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 45, 927–945.

Lobo, A., Perez-Echeverria, M. J., Jimenez, A., & Sancho, M. A. (1988). Emotional disturbances in endocrine patients. Validity of the scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28). The British Journal of Psychiatry, 152(6), 807–812.

Lockhart, G., MacKinnon, D. P., & Ohlrich, V. (2011). Mediation analysis in psychosomatic medicine research. Psychosomatic Medicine, 73(1), 29–43.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552.

Mickelson, K. D., Kessler, R. C., & Shaver, P. R. (1997). Adult attachment in a nationally repre- sentative sample. Journal of Personality y Social Psychology, 73, 1092–1106.

Montero-Marin, J., Gaete, J., Demarzo, M., Rodero, B., Lopez, L. C., & García-Campayo, J. (2016). Self-criticism: a measure of uncompassionate behaviors toward the self, based on the negative components of the self-compassion scale. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01281

Montero-Marin, J., Navarro-Gil, M., Puebla-Guedea, M., Luciano, J. V., Van Gordon, W., Shonin, E., & Garcia-Campayo, J. (2018). Efficacy of ‘attachment-based compassion therapy’ (ABCT) in the treatment of fibromialgia: a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00307

Morris, S. B. (2008). Estimating effect sizes from pretest-posttest-control group designs. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 364–386.

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250.

Neff, K.D. (2012). Sé amable contigo mismo. El arte de la compasión hacia uno mismo. Barcelona. Onir.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 28–44.

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 908–916.

Pace, T. W., Negi, L. T., Adame, D. D., Cole, S. P., Sivilli, T. I., Brown, T. D., et al. (2009). Effect of compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune and behavioral responses to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(1), 87–98.

Pepping, C. A., O’Donovan, A., & Davis, P. J. (2014). The differential relationship between mindfulness and attachment in experienced and inexperienced meditators. Mindfulness, 5, 392–399.

Pepping, C. A., Davis, P. J., & O’Donovan, A. (2015). The association between state attachment security and state mindfulness. PLoS One, 10(3), e0116779.

Raque-Bogdan, T. L., Piontkowski, S., Hui, K., Ziemer, K. S., & Garriott, P. O. (2016). Self-compassion as a mediator between attachment anxiety and body appreciation: an exploratory model. Body Image, 19, 28–36.

Ruiz, F. J., Langer Herrera, A. I., Luciano, C., Cangas, A. J., & Beltrán, I. (2013). Measuring experiential avoidance and psychological inflexibility: the Spanish version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire—II. Psicothema, 25(1), 123–129.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., Compare, A., Zangeneh, M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). Buddhist-derived loving-kindness and compassion meditation for the treatment of psychopathology: a systematic review. Mindfulness, 6, 1161–1180.

Shonin, E., Van Gordon, W., Garcia-Campayo, J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Can compassion help cure health-related disorders? British Journal of General Practice, 67, 177–178.

White, I. R., Horton, N. J., Carpenter, J., & Pocock, S. J. (2011). Strategy for intention to treat analysis in randomised trials with missing outcome data. British Medical Journal, 342, d40.

Yárnoz-Yaben, S. (2010). Attachment style and adjustment to divorce. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13, 210–219.

Yárnoz-Yaben, S., & Comino, P. (2011). Evaluación del apego adulto: análisis de la convergencia entre diferentes instrumentos [Assessment of adult attachment: analysis of the convergence between different instruments]. Acción Psicológica, 8(2), 67–85.

Yárnoz-Yaben, S., Alonso-Arbiol, I., Plazaola, M., & Sainz de Murieta, L. M. (2001). Apego en adultos y percepción de los otros. Anales de Psicología, 17, 159–170.

Funding

We appreciate the support provided by the Research Network on Preventative Activities and Health Promotion (RD06/0018/0017) and the Aragon Health Sciences Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MNG designed and executed the study and assisted with the writing of the manuscript. YLH designed and assisted with the writing of the manuscript. MMA executed the study and collaborated in the editing of the manuscript. WVG collaborated in the writing of the final manuscript. ES collaborated in the writing of the final manuscript. JMM developed the data analyses and assisted with the writing of the results and the manuscript. JGC designed and executed the study and collaborated in the writing of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Aragon Ethical Committee (Spain). All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Aragon Ethical Committee), and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Navarro-Gil, M., Lopez-del-Hoyo, Y., Modrego-Alarcón, M. et al. Effects of Attachment-Based Compassion Therapy (ABCT) on Self-compassion and Attachment Style in Healthy People. Mindfulness 11, 51–62 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0896-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0896-1