Abstract

Some influential studies show that many self-employed could apparently achieve higher earnings were they working in paid employment. One potential explanation for this “return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle”, not empirically tested yet, is that entrepreneurship entails non-monetary benefits, such as autonomy, flexibility, and task variety. Using German data and a decomposition analysis, I examine the contribution of these working conditions to the observed earnings differential between self-employment and paid employment. I confirm that self-employed individuals report lower earnings than what they are expected to earn in paid employment. However, differences in working conditions barely contribute to the earnings gap. This finding casts some doubt on the relevance of compensating differentials for explaining the return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle.

Zusammenfassung

Verschiedene einflussreiche Studien haben gezeigt, dass viele Selbständige scheinbar höhere Einkünfte erzielen könnten, wenn sie stattdessen als abhängig Beschäftigte tätig wären, ein Befund, der in der Literatur als „return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle“ bekannt ist. Ein möglicher Erklärungsansatz dafür, der bisher empirisch nicht überprüft wurde, ist, dass die Selbständigkeit im Gegenzug nicht-monetäre Vorteile wie etwa mehr Autonomie, Flexibilität und Abwechslung mit sich bringt. Mittels einer Zerlegungsanalyse untersuche ich auf Grundlage deutscher Daten, inwiefern Unterschiede in solchen Arbeitsbedingungen den gemessenen Verdienstunterschied zwischen Selbständigkeit und abhängiger Beschäftigung erklären können. Ich bestätige, dass Selbständige niedrigere Einkünfte angeben als ihren erwarteten Einkünfte in abhängiger Beschäftigung entspricht. Allerdings tragen Unterschiede in den Arbeitsbedingungen kaum zum Verdienstunterschied bei. Dies lässt Zweifel an der Relevanz kompensierender Differentiale als Erklärung für das return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle aufkommen.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

“What motivates entrepreneurship?” is one of the most investigated questions in entrepreneurship research, and governments aiming at providing incentives for entrepreneurship naturally depend on an accurate answer to that question. One prominent idea which has also been incorporated in many economic models on occupational choice is that people choose entrepreneurship because it is financially rewarding to do so (see, e.g., de Wit 1993 for a survey of some classical models on occupational choice). Quite in contrast to this idea, some influential studies find that entrepreneurship does not seem to pay in monetary terms. For instance, in a widely cited article, Hamilton (2000) finds that most self-employed would apparently have significantly higher earnings if they were working as paid employees. Moskowitz and Vissing-Jørgensen (2002) show that the returns to the investment in privately held firms are no higher than the returns to public equity despite the higher risk associated with private equity. Benz (2009, p. 23) eventually concludes that “entrepreneurship does quite generally not pay in monetary terms,” a finding that has been termed the “return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle” in the literature (e.g., Hyytinen et al. 2013; see Åstebro 2012 for an extensive survey on the returns to entrepreneurship).

One potential explanation for low monetary returns to entrepreneurship is that there are nonmonetary benefits associated with this occupation that compensate for the lower monetary rewards (cf. Hamilton 2000; Moskowitz and Vissing-Jørgensen 2002; see Rosen 1986 for a basic discussion of the theory of compensating differentials).Footnote 1 There is indeed a large body of literature showing that the self-employed report higher job satisfaction and that this can be attributed to having more beneficial working conditions like more variety, flexibility, and autonomy (e.g., Hundley 2001; Benz and Frey 2008; Schjoedt 2009; Millán et al. 2013; Lange 2012).Footnote 2 It seems thus natural to assume that there is a trade-off between these beneficial working conditions and earnings in self-employment that accounts for the apparently low returns to entrepreneurship. Croson and Minniti (2012) develop a theoretical model based on this idea that implies that the self-employed will in fact have (initially) lower earnings in exchange for more beneficial working conditions. Åstebro and Thompson (2011) also argue that entrepreneurs may be willing to forego earnings to satisfy a taste for variety. Finally, Benz (2009, p. 23) even states - somewhat provocatively - that entrepreneurship is not mainly about making money but is “more adequately characterized as a non-profit-seeking activity.”

While this reasoning seems sensible at first glance, it remains somewhat speculative since its empirical underpinning is rather limited. To the best of my knowledge, there is no study examining the potential contribution of working conditions such as flexibility, variety, and autonomy at the workplace to the observed earnings differential between self-employed and paid employees.Footnote 3 Thus, it is rather unclear by what amount the returns to entrepreneurship should actually be higher if self-employment did not offer better working conditions than paid employment. What is more, the reasoning above seems to neglect the fact that self-employment is also associated with a lot of uncomfortable working conditions. The self-employed face more exposure to risk and uncertainty (see, e.g., Parker 2009, Chap. 13.4), work much more hours than paid employees do (cf. Hyytinen and Ruuskanen 2007), and eventually report working under a lot of pressure, coming home from work exhausted, losing sleep over worry, and being constantly under strain (cf. Blanchflower 2004).

The present study seeks to address these concerns with the current state of the literature. Using a rich German data set, I perform a decomposition analysis including beneficial working conditions such as flexibility, autonomy, and variety as well as detrimental working conditions such as exposure to risk, pressure, and overstrain as explanatory variables. There are at least two intricacies one faces when examining the earnings differential between self-employment and paid employment. First, the earnings differential may in part be due to measurement problems of entrepreneurial earnings. For instance, in a recent study using U.S. data, Åstebro and Chen (2014) show that there is actually a large earnings premium to entrepreneurship after correcting for mis-measurement of earnings. The advantage of a decomposition analysis is that it allows one to decompose the earnings differential in a part that can be explained by working conditions and other observable characteristics, and a part that remains unexplained and potentially reflects mis-measurement of earnings. Second, the earnings differential is probably not only due to differences in observable characteristics between self-employed and paid employees but also due to unobservable characteristics. Given that the data set used is only cross-sectional, it is hardly possible to account for unobserved heterogeneity. Nevertheless, I will address the issue of selection into paid employment and self-employment, respectively, by a Heckman (1979) selection correction.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, I describe the data set and the measurement of earnings and working conditions. Section 3 provides descriptive evidence. Section 4 analyzes the earnings differential between self-employed and paid employees using hedonic earnings regressions and decomposition analyses. I conclude with a discussion of the results in Section 5.

2 Data and variables

The data set used in this study is the BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey of the Working Population on Qualification and Working Conditions in Germany 2012 (Hall et al. 2014; see Rohrbach-Schmidt and Hall 2013 for a more detailed description). This representative data set contains information on more than 20,000 individuals from the German active labor force population who are at least 15 years old and regularly work at least 10 h per week. It provides exceptionally rich information on human capital endowments, job characteristics and in particular the working conditions of individuals, which makes it especially suitable for the present analysis.Footnote 4

As is most often done in the literature, self-employment will be used as the empirical realization of “entrepreneurship” in this paper.Footnote 5 The group of the self-employed in the data consists of tradesmen and liberal professionals, coded as “Selbständige” and “freiberuflich Tätige” in the data set. The comparison group of paid employees consists of blue- and white-collar workers, but I exclude civil servants from the analysis because this group differs considerably from other paid employees with respect to working conditions and wage-setting, and civil service may not be the relevant outside option that most self-employed face. Freelance collaborators and helping family members are also excluded from the analysis since they are neither typical self-employed nor paid employees. The analysis sample then consists of 13,287 individuals who report income data and have no missing covariates. These include 800 male and 499 female self-employed individuals as well as 5552 male and 6436 female paid employees.

Turning to the measurement of the crucial variables for this study, the measurement of self-employment earnings is tricky (see Parker 2009, pp 363–372). First of all, entrepreneurial income not only comprises money drawn from the business, but also retained profits. In the BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey 2012 the self-employed were asked:

Now to your monthly gross earnings. We do not mean your monthly turnover or profit. Do not include child allowance, please. What are your monthly gross earnings from your work as <job of interviewee>?

This measure of self-employment earnings may roughly correspond to “draw”, the money drawn from the business on a regular basis by the owner (cf. Parker 2009, p. 363), but as only net earnings can be retained it is not entirely clear which income concept is captured by this question.Footnote 6 Second, it has been found that self-employment earnings usually suffer from large non-response rates and considerable underreporting (e.g., Engström and Holmlund 2009; Sarada 2010; Hurst et al. 2014; Krichevskiy 2011, Chap. 4).Footnote 7

The question on the wages of paid employees in the BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey 2012 is:

Now to your monthly gross earnings, i.e., your wage before taxes and social security contributions. Do not include child allowance, please. What are your monthly gross earnings from your work as <job of interviewee>?

The comparison between self-employment earnings and wages of paid employees is further complicated because self-employment earnings include capital income whereas paid employees’ wages do not. At the same time, reported wages of paid employees do not account for employer-provided fringe benefits or partial takeover of social security contributions.Footnote 8 Faulenbach et al. (2007) show that the majority of paid employees in Germany would have to generate higher gross earnings in self-employment in order to yield the same amount of net earnings and social security coverage as in paid employment.

All in all, it seems obvious that part of the difference in earnings between self-employed and paid employees is probably due to measurement problems of earnings. This poses no problem for the investigation of the role of working conditions for the earnings differential, though. It is still possible to decompose the earnings differential in a part that can be explained by differences in working conditions (and other observable characteristics), while mis-measurement will be picked up by the “unexplained” part in the decomposition analysis. The role of five sorts of working conditions is considered in this study: (1) flexibility, (2) autonomy, (3) variety, (4) risk, and (5) work stress.

Interviewees were asked about the flexibility of their working time scheduling in the following way:

How often are you able to take family and private interests into account when scheduling working time?

Possible answers were often, sometimes, and never. Since only very few people answered “never,” I constructed a dummy variable with categories 1 = often and 0 = sometimes or never.Footnote 9

Two variables capture autonomy at work. Autonomy can be low if individuals have to follow detailed instructions on what they have to achieve and/or if they are given regulations on how to perform their work. These aspects were queried in the following ways:

How often does it happen in your job that you are instructed to produce a precise number of items, provide a certain minimum performance or do a particular work in a specified time?, and

How often does it happen in your job that you are given highly specific regulations on how to perform your work?

For both questions possible answers were often, sometimes, rarely, and never. In each case I constructed a dummy with 1 = rarely or never and 0 = often or sometimes, such that 1 indicates less regulations and thus more autonomy. I refer to the variable based on the first question as “work outcome not prescribed in detail” in the tables, and call the other one “free how to perform work”.

The questions on variety were asked in a similar fashion, i.e., it was asked how often certain working conditions appeared at work with possible answers being often, sometimes, rarely and never. Consequently, the respective dummies were also constructed in a similar fashion, with 1 indicating more variety. There are three dummies capturing three different aspects of variety at work: repetitive work (1 = sometimes, rarely or never), facing new tasks (1 = often) and trying new things or improving extant processes (1 = often). The specific questions asked are:

How often does it happen in your job that a certain work process repeats in detail?,

How often does it happen in your job that you face new tasks that you first have to think about and work out?, and

How often does it happen in your job that you improve extant processes or try out new things?

Turning now to the less beneficial working conditions, there are two alternative ways how to include risk in the analysis. Interviewees were asked:

How often does it happen in your job that even a small mistake or a minor inattentiveness could cause bigger financial losses?

Again, possible answers were often, sometimes, rarely, never and the respective dummy was coded with 1 indicating often or sometimes. A potential problem with this measure of risk could be that it may not be comparable across self-employment and paid employment. The self-employed presumably would have to bear the financial losses themselves if they made a small mistake. On the contrary, big financial losses that are caused by a minor inattentiveness (and not by gross negligence) might hit partly or even primarily the firm for which paid employees work instead of the responsible employee herself. For this reason, I utilize a more subjective measure of risk in the main estimations (and use the other one as a robustness check). If an interviewee answered “often” to the question above, she was subsequently asked:

Is this a strain for you?

From this a dummy was derived, coded 1 if an interviewee was exposed to risk often and this was actually a strain for her, and 0 if either there was little exposure to risk or the individual did not care.

Finally, two variables take account of the stressful and demanding nature of the work of the self-employed. One indicates whether individuals have to work under a lot of pressure (1 = often):

How often does it happen in your job that you have to work under a lot of pressure of time or to perform?

The other one indicates whether the work of individuals is rather challenging and possibly overcharging (1 = often or sometimes):

How often does it happen in your job that you have to reach the limits of your capabilities?

This variable is labeled “overstrain” in the tables.

Table 1 displays the correlation matrix of the ten working condition indicators. Generally, the correlation between the different indicators is not very high. That implies that, for instance, the different measures of autonomy and variety actually capture different aspects of these working conditions.

3 Descriptive evidence

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics of the estimation sample. It is conspicuous that the self-employed on average report higher earnings than paid employees do. Self-employed men report monthly gross earnings of € 4627, whereas male paid employees only report earnings of € 3461 on average. For women, reported earnings of the self-employed are also higher than those of female paid employees, amounting to 2520 and € 2168, respectively. This difference in monthly earnings is partly due to the self-employed working more hours than paid employees on average (48.0 vs. 42.5 and 39.6 vs. 33.5 h per week for male and female workers, respectively). Still, hourly earnings (i.e., monthly earnings divided by 4.3 times weekly working hours) of self-employed men are also higher than those of male paid employees, amounting to 23.3 and € 18.8, respectively. Self-employed women also report slightly higher hourly earnings than female paid employees on average, but the difference is not statistically significant.Footnote 10 It is important to note that these figures do not indicate whether entrepreneurship pays. First, given the described measurement problems, it is not clear from these figures what the relative earnings position of the self-employed really is. Second, even if one took the earnings data at face value, the reported figures would not imply that entrepreneurship pays. The self-employed may simply be a positive selection and might earn even more were they working in paid employment.Footnote 11

The data show that the self-employed indeed seem to be a distinctly positive selection in terms of some characteristics related to earnings (cf. Table 2): The share of those having a university degree is as much as two times higher for the self-employed than for paid employees (44 vs. 22 and 41 vs. 20 % for male and female workers, respectively), and the self-employed have considerably more working experience than paid employees have on average (28.5 vs. 24.3 and 26.0 vs. 25.4 years for male and female workers, respectively). It is thus not surprising that the self-employed report higher earnings, but it is an open question whether they would be better off working in paid employment.

As laid down in the introduction, some authors argue that entrepreneurs earn less than what they could earn as paid employees because the former have more beneficial working conditions than the latter. Working conditions that are frequently mentioned in this context are autonomy, variety, and flexibility. It is intuitively appealing that entrepreneurs should have more autonomy, variety, and flexibility because they do not have to follow instructions received from any boss, and so presumably can choose what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. Table 2 shows that the work of the self-employed indeed entails more autonomy and variety than that of paid employees. Both male and female self-employed more often report having autonomy and variety at work than their counterparts in paid employment, regardless of which indicator one uses for autonomy and variety. However, the self-employed apparently do not have more flexibility than paid employees as only 56 % of male and 57 % of female self-employed often report being able to take family and private interests into account when scheduling their working time, whereas this is the case for 58 and 62 % of male and female paid employees, respectively. This finding may stem from the fact that self-employed work more hours, which may prevent them from better taking family and private interests into account, despite that they should principally have more freedom over the timing of their work.

Entrepreneurship is not only associated with some beneficial working conditions, but the entrepreneur is also characterized as having to bear a higher degree of uncertainty and risk (dating back to Knight 1921 and Kihlstrom and Laffont 1979), and Blanchflower (2004) found that the self-employed face more stresses and strains compared to paid employees. Regarding risk, Table 2 shows that the self-employed are indeed more often exposed to risk than paid employees, and that the share of those being exposed to risk that actually feel strained by risk is also higher among the self-employed than among paid employees (indicating that the self-employed indeed have to bear the consequences of their mistakes, i.e., the “big financial losses,” themselves, while this may only partly be true for paid employees). For male self-employed, it is also true that they work more often under a lot of pressure and overstrain than male paid employees, but female self-employed do not seem to experience more pressure and overstrain than their regularly employed counterparts.

All in all, the descriptive evidence indicates that the self-employed experience more of certain beneficial working conditions such as autonomy and variety, but at the same time also more of certain detrimental working conditions, namely, risk, pressure, and overstrain (although the latter does not hold true for all subgroups of self-employed workers). To what extent these differences in working conditions may explain earnings differences between the occupations will be examined in the next section.

4 Working conditions and the self-/paid employment earnings gap

Before turning to a decomposition analysis, consider some simple OLS earnings regressions as displayed in Table 3. The table displays the results of regressions of logarithmic gross hourly earnings on a self-employment dummy and several control variables. The BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey 2012 contains exceptionally rich information on characteristics of individuals and in particular the jobs they perform, which enables one to account for a large set of control variables. To begin with, interviewees were asked about the specific skill requirements at their jobs. For eight different areas they were to state whether their work required basic or expert knowledge in this area. Examples are technical skills, economic skills, math skills, and legal knowledge. I include 16 dummies for basic and expert skills in these eight areas as control variables in the regressions. Further controls for human capital are the highest professional qualification (four dummies) and actual general and specific working experience. Actual general working experience is known because interviewees were asked when they were employed for the first time and also what the total amount of time of working intermissions was. Both variables are measured in years and included in the regressions in linear and squared form. Specific working experience is measured as tenure, i.e., years running the current business (years working at the current workplace for paid employees, respectively), and is also included in the regressions in linear and squared form. Regarding the job characteristics of individuals, interviewees were also asked in what tasks they were engaged. Examples are producing goods, quality control, purchasing or selling, advertising or marketing, etc. There were 17 tasks altogether, so I include 17 dummies capturing the tasks occurring at work. Additionally, eleven dummies capture the physical working environment of individuals, for instance, whether they were exposed to noise, dirt, or coldness.Footnote 12 Finally, several socio-demographic variables (migration background, family status, place of residence) are included as control variables.

The regression results (columns 1 and 3 of Table 3) show that self-employed men report about 6.9 % lower hourly earnings on average than male paid employees with comparable skills and jobs (statistically significant at the 5 % level), while female self-employed even report 18.0 % lower hourly earnings than comparable paid employees (statistically significant at the 1 % level). Hence, once accounting for observable characteristic the typical result shows up that self-employed individuals report lower earnings than paid employees do, ceteris paribus.

In columns 2 and 4 of Table 3, working conditions are added to the regressions. Still, the self-employment dummy barely changes (it is even slightly lower), which casts some doubt on the idea that differences in working conditions are crucial for lower self-employment earnings. The nine working conditions indicators are jointly statistically significant at the 1 % level for both men and women. However, several working conditions are not individually statistically significant and/or do not have the expected signs. The theory of compensating differentials implies that job amenities are associated with lower wages, ceteris paribus, while stresses and strains are associated with higher wages. The coefficients of the variables capturing flexibility, autonomy, and task variety should thus be negative, whereas those capturing risk, pressure, and overstrain should be positive. Quite in contrast, flexible working time scheduling is associated with 4.1 and 4.3 % higher earnings for men and women, respectively (statistically significant at the 1 % level), and non-repetitive work is associated with 4.5 and 4.3 % higher earnings for men and women, respectively (statistically significant at the 1 % level). Being free how to perform work goes along with 2.4 % higher earnings for women (statistically significant at the 5 % level), but is not statistically different from zero in the regression for men, while often facing new tasks is associated with 2.6 % higher earnings in the regression for men (statistically significant at the 5 % level) but not statistically significant in the regression for women. One reason why these working conditions do not show the expected signs might be ability bias (cf. Borjas 2013, pp. 222–223). Although the data set used in this analysis provides exceptionally rich information on the human capital of individuals usually not available in other data sets (e.g., the precise skill requirements at work), there could still be unobserved ability which may be positively correlated with earnings and job amenities at the same time. Given that the data set is only cross-sectional, I am not able to rule out this type of unobserved heterogeneity.Footnote 13 That said, some unpleasant working conditions do exhibit the expected signs: Being under pressure to perform goes along with 4.3 % higher earnings for men (statistically significant at the 1 % level), consistent with compensating differentials, and is positively associated with earnings but not statistically significant for women. For women, experiencing overstrain at work is associated with 2.8 % higher earnings (statistically significant at the 5 % level), but the respective coefficient is slightly negative and not statistically significant for men.

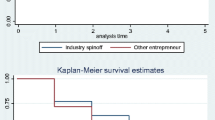

A serious investigation of the returns to entrepreneurship requires a more thorough examination of the earnings gap between self-employment and paid employment than just presented. First of all, it is clear that the determinants of earnings differ between self-employment and paid employment, not least because “earnings” has different meanings in the two occupations. Thus, it would be more sensible to run regressions separately for self-employed and paid employees. These regressions can then be used to predict counterfactual earnings for one group using the coefficients of the earnings regression of the other group (the latter being called the “reference group”), providing an answer to the question what earnings the self-employed would probably report were they working as paid employees.

A problem with this approach might arise, however, if individuals did not randomly select into paid employment, but based on some characteristics that are unobservable and can thus not be controlled for. In this case, the coefficients of the wage regression using only the group of paid employees would suffer from selection bias and could not be used to consistently predict wages for self-employed workers. This issue can be addressed by performing a Heckman (1979) selection correction. A pitfall of this approach is that it requires a proper exclusion restriction, i.e., a variable that is correlated with working in paid employment but not influencing wages (directly).Footnote 14 One variable that may by and large meet these conditions could be age. Since formal education and actual working experience, intermissions, and tenure are already controlled for in the wage regressions, age should not pick up any human capital endowments. At the same time, age is positively related to the probability of being self-employed, for instance, because older people are more likely to have received inheritances which could be used to overcome borrowing constraints, and older people may choose self-employment instead of paid employment to avoid mandatory retirement provisions (cf. Parker 2009, Chap. 4.2.1). Age is also associated with risk aversion, which may influence selection into occupations and earnings at the same time, but “strained by risk” should account for the impact of risk on earnings. Still, age is no perfect exclusion restriction, for instance, because it is also associated with health status, which may influence selection into occupations and wages at the same time. Another variable that has already frequently been used as an exclusion restriction in the extant literature is the self-employment status of a parent (see, e.g., Fossen 2012; Constant and Shachmurove 2006). Having a self-employed parent increases the likelihood of being self-employed instead of working in paid employment (cf. Parker 2009, p. 108), while there is no obvious reason why having a self-employed parent should have a direct influence on the wages of paid employees.Footnote 15 The BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey 2012 contains information on the self-employment status of the father or the mother of the interviewee at the age of 15. When including age (linear and squared) and a dummy indicating self-employment of a parent in a Probit regression (additionally to all other control variables and working conditions), they turn out to be significantly related to paid employment for both men and women (at the 1 % level).Footnote 16 Thus, the inverse Mill’s ratios based on these Probit regressions are calculated and included in the wage regressions to account for selection on unobservables.

The selectivity-corrected earnings equations in entrepreneurship and salaried work can then be written as

where e refers to entrepreneurship and w to wage work. λ denotes the inverse Mill’s ratio calculated as

and

for selection in entrepreneurship and paid employment, respectively. Z includes the explanatory variables X and additionally the exclusion restrictions self-employed parent and age, and \(\phi (.)\) and \(\Phi (.)\) denote the standard normal pdf and cdf, respectively. The mean earnings differential between paid employees and self-employed amounts to

which after some short manipulation yields

where PE and SE denote mean values for paid employees and self-employed, respectively (and paid employees form the reference group). In particular, \({{\overline{\lambda }}_{w,SE}}\) is the mean value of the inverse Mill’s ratio for self-employed if the self-employed faced the same selection equation that paid employees face (cf. Neuman and Oaxaca 2004, p. 6). I refer to the explained part of the earnings gap as the one that can be attributed to differences in personal attributes in observables \(({{\overline{X}}_{PE}}-{{\overline{X}}_{SE}}){{\beta }_{w}}\) as well as to differences in personal attributes that determine the probability of paid employment \((\bar{\lambda }w,PE\bar{\lambda }w,SE)\theta w\) (cf. Neuman and Oaxaca 2004, p 7). \(\bar{X}SE(\beta w\beta e)+\bar{\lambda }w,SE\theta w\bar{\lambda }e,SE\theta e\) is the part of the earnings differential that cannot be attributed to endowment differences between the groups, and will be denoted as unexplained.Footnote 17

Table 4 presents the results of Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions (Oaxaca 1973; Blinder 1973) of the logarithmic hourly earnings differential between self-employment and paid employment including the same control variables and working conditions as before, as well as the calculated inverse Mill’s ratios. I use paid employees as the reference group, i.e., the decomposition is based on predicting counterfactual wages for the group of the self-employed using the coefficients of the earnings regression for paid employees. This seems sensible because predicting wages is definitely easier than predicting self-employment earnings, and taking paid employees as the reference group may thus yield more reliable results (nevertheless, my conclusions do not change if I use the self-employed as the reference group in a robustness check).Footnote 18 The mis-measurement of earnings poses no problem for the decomposition analysis. First, since the coefficients of the wage regressions that are used to predict counterfactual wages are estimated using only the group of paid employees, potential mis-measurement of self-employment earnings does not matter in this regard. Second, even if there was also mis-measurement of wages, this generally would not invalidate the OLS coefficients but only increase standard errors (provided the extent of mis-measurement is uncorrelated with the explanatory variables, see, e.g., Wooldridge 2010, Chap. 4.4.1). That said, the potential mis-measurement of self-employment earnings does have an influence on the measured overall earnings gap, as well as on the relative sizes of the unexplained and explained part. Thus, the reported overall earnings gap should not be interpreted as the true earnings differential, and it is not possible to identify the relative contribution of differences in working conditions and other explanatory variables as a share of the true earnings gap. Still, the contributions of the explanatory variables can reasonably be interpreted in terms of the (mis-)measured earnings gap, i.e., they show to what extent differences in observed characteristics contribute to the actually observed earnings differential.

As can be seen in column 1 of Table 4, male self-employed on average report approximately 6.7 % higher earnings than male paid employees. The “unexplained” part of the earnings differential, however, indicates that predicted wages of the self-employed are 9.4 % higher than reported self-employment earnings, i.e., the self-employed report lower earnings than what they are expected to earn in paid employment. For female workers on the other hand, the raw earnings gap appears to be positive, while the “unexplained” part of the gap is much higher than for male workers: Expected wages for self-employed women are on average approximately 20.0 % higher than their reported self-employment earnings (column 3).Footnote 19

The largest contribution to explaining the earnings differential between the self-employed and paid employees is made by human capital endowments. Differences in human capital endowments explain a differential of 9.7 and 5.5 % points for men and women, respectively. Differences in the propensity of selecting into paid employment, as captured in the inverse Mill’s ratio, probably also contribute to the earnings differential between self-employed and paid employees to some extent. While the respective coefficients are only statistically significant at the 20 and 10 % level for men and women, respectively, the contribution of 4.2 and 2.6 % points, respectively, appears to be economically significant.

Coming to the main variables of interest in this study, the contribution of working conditions to the observed earnings differential is quite limited. Neither flexibility, autonomy, strain by risk, nor pressure and overstrain contribute to the earnings differential in a statistically significant way and the respective coefficients are all smaller than 1 %. Only variety is statistically significant (at the 1 % level), but it has the “wrong” sign. Having more variety at work contributes to 0.7 and 1.2 % higher self-employment earnings relative to paid employees’ wages for men and women, respectively. This is not consistent with the idea that the self-employed accept lower earnings in exchange for more variety at work. Thus, all in all, the differences in the working conditions examined in this study do not seem to be crucial for explaining the return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle.

This insight still holds when performing a number of robustness checks. First of all, it could be argued that comparing average earnings is not very meaningful given that entrepreneurial earnings are distinctly positively skewed (although taking logs somewhat alleviates the problem). Thus, I also conducted decompositions of the median earnings differential, utilizing the concept of RIF regression as described in Fortin et al. (2011). For this, one can run usual OLS regressions and Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions, but the dependent variable is replaced by the recentered influence function (RIF) of its median.Footnote 20 The results of the respective Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions are displayed in columns 2 and 4 of Table 4. Several other robustness checks are not reported in tables but are available on request: Instead of paid employees, I used the self-employed as the reference group; I excluded extreme values of the logarithmic hourly earnings distribution (higher than the 75 % quantile plus 1.5 times the interquartile range and lower than the 25 % quantile minus 1.5 times the interquartile range, respectively); I used “exposure to risk” instead of “strained by risk”; I additionally included 12 occupational area dummies; I included dummies for each possible answer category of the working conditions instead of binary variables, thus using all available variation in working conditions; I included the variables used as exclusion restrictions, i.e., age and self-employment of parents, directly (instead of the inverse Mill’s ratios) or just dropped the inverse Mill’s ratios (without replacing them with the exclusion restrictions); I used monthly instead of hourly earnings as the dependent variable and controlled for logarithmic working hours; finally, I differentiated between solo self-employed (i.e., self-employed without any other employees) and self-employed who also employ other workers. By and large, the contribution of working conditions also remained insignificant and/or inconsistent with the idea of compensating differentials in these cases, the only exception being “pressure and overstrain”, which was small but positive statistically significant in the case of female solo self-employed.

5 Conclusions

Some influential studies find that entrepreneurship does apparently not pay in monetary terms (cf. Hamilton 2000; Moskowitz and Vissing-Jørgensen 2002). One prominent potential explanation for this finding is that entrepreneurs trade off earnings against more beneficial working conditions such as flexibility, autonomy, and variety. This study examined to what extent differences of working conditions between self-employment and paid employment may contribute to the observed earnings differential between the two occupations.

I find that the raw earnings gap between paid employees and self-employed individuals is negative, i.e., the self-employed report higher earnings than paid employees on average. Still, once accounting for differences in observable characteristics, in particular human capital, I obtain the usual result that the self-employed on average have lower reported earnings than paid employees, ceteris paribus. Using an Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition, and taking account of selection on unobservables by a Heckman selection correction, I do not find that working conditions such as flexibility, autonomy, and variety contribute to explaining the lower selfemployment earnings.

In a way, this finding may not be that surprising, given that the self-employed are generally found to report higher levels of job satisfaction than paid employees. If more comfortable working conditions were (fully) compensated for by having lower earnings, this pronounced satisfaction difference should not be observed. In a competitive market with free self-employment entry, individuals would switch between self-employment and paid employment until the earnings in each sector adjust, so as to equalize the marginal workers’ net utilities derived from the two occupations. The fact that the self-employed still seem to be able to enjoy more beneficial working conditions than paid employees, apparently without having to pay for this, implies that there exist barriers to self-employment (cf. Kawaguchi 2008), and that these barriers impede the emergence of compensating earnings differentials. If this is actually the case, there would clearly be scope for governmental interventions removing (some of) the obstacles that hinder people to become self-employed.Footnote 21

A limitation of my analysis is that it is based on a cross-sectional data set. Although this data set provides rich information on the human capital of individuals, including the precise skill requirements at work, I cannot rule out that there is still some unobserved ability which may be positively correlated with earnings and job amenities at the same time. This limitation may also partly explain why I do not find that working conditions differences contribute to earnings differences between the self-employed and paid employees.

Besides addressing this issue of unobserved ability, future research on the returns to entrepreneurship should possibly primarily be concerned with figuring out how large the income difference between self-employment and paid employment really is. Since “the bulk of previous work (including the influential article of Hamilton, 2000) has not paid sufficient attention to problems of income under-reporting and other sources of mismeasurement, (…) it is far from clear what the relative average income position of entrepreneurs really is” (Parker 2009, p. 382). In a recent study, Åstebro and Chen (2014) find a self-employment earnings premium of 42 % in the US when correcting for underreporting. Therefore, it could as well be that entrepreneurship is not only favorable in terms of providing nice working conditions like autonomy and task variety but that it also pays in monetary terms. This would be consistent both with the stylized fact that entrepreneurs are much more satisfied with their work than paid employees and with the result of the analysis at hand that entrepreneurs do not have to forego earnings in order to enjoy more beneficial working conditions.

6 Kurzfassung

Ökonomische Modelle unterstellen typischerweise, dass Menschen sich selbständig machen, weil es sich finanziell gesehen lohnt. Verschiedene empirische Studien deuten jedoch darauf hin, dass die meisten Selbständigen als abhängig Beschäftigte höhere Einkünfte erzielen könnten. Dieser Befund ist in der Literatur als „return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle“ bekannt. Erklärungsansätze umfassen zum einen, dass Unternehmerverdienste und Löhne nicht ohne weiteres vergleichbar sind und Selbständige dazu neigen, ihre Einkünfte zu niedrig auszuweisen. Zum anderen wird spekuliert, dass Selbständige finanzielle Nachteile im Austausch für angenehmere Arbeitsbedingungen hinnehmen, der Verdienstnachteil also ein kompensierendes Lohndifferential darstellt. In der vorliegenden Studie wird meines Wissens erstmals letzterer Erklärungsansatz empirisch überprüft.

Auf Basis einer Stichprobe von rund 13.000 Erwerbstätigen, die im Rahmen der BIBB/BAuA Erwerbstätigenbefragung 2012 befragt wurden, untersuche ich, wie sich die Verdienste und Arbeitsbedingungen von Selbständigen und abhängig Beschäftigten unterscheiden, und inwieweit Unterschiede in den Arbeitsbedingungen den gemessenen Verdienstunterschied erklären können. Ich finde zunächst, dass Selbständige im Durchschnitt höhere Brutto-Verdienste aufweisen als abhängig Beschäftigte. Nach Berücksichtigung von Unterschieden in beobachtbaren Merkmalen von Selbständigen und abhängig Beschäftigten wie bspw. Bildungsstand, Arbeitsmarkterfahrung, Fähigkeiten und Tätigkeitsbereiche, ergibt sich jedoch der erwartete Befund, dass der gemessene Verdienst bei Selbständigen ceteris paribus niedriger ist als bei abhängig Beschäftigten.

Um zu klären, ob der niedrigere Verdienst auf Unterschiede in den Arbeitsbedingungen zurückgeführt werden kann, betrachte ich fünf verschiedene Arbeitsbedingungen (abgegriffen durch neun Indikatorvariablen): Flexibilität bei der Arbeitszeitplanung, Autonomie, abwechslungsreiche Arbeit, Belastung durch finanzielle Risiken, und Stress (letzterer abgegriffen durch starken Termin- oder Leistungsdruck und Arbeiten an der Grenze der Leistungsfähigkeit). Es zeigt sich, dass Selbständige höhere Autonomie und abwechslungsreichere Arbeit haben als abhängig Beschäftigte, jedoch nicht mehr Arbeitszeitflexibilität. Gleichzeitig sind Selbständige stärker dem Risiko ausgesetzt, dass kleine Fehler große finanzielle Verluste zur Folge haben könnten und sie arbeiten unter größerem Stress (letzteres gilt allerdings nur für männliche Selbständige).

Im Rahmen einer Zerlegungsanalyse zeige ich, dass diese Unterschiede in den Arbeitsbedingungen allerdings keinen nennenswerten Beitrag zur Erklärung des Verdienstunterschieds zwischen Selbständigen und abhängig Beschäftigten leisten. Insofern erscheint es zweifelhaft, ob kompensierende Lohndifferentiale entscheidend zur Erklärung des „return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle“ beitragen.

Dieses Ergebnis steht im Einklang mit zahlreichen Studien, die finden, dass Selbständige deutlich zufriedener mit ihrer Arbeit sind als abhängig Beschäftigte, ein Befund, der sich so nicht zeigen sollte, wenn bessere Arbeitsbedingungen durch schlechtere Verdienstmöglichkeiten weitestgehend kompensiert würden. Es liegt somit vielmehr die Vermutung nahe, dass konzeptionelle Unterschiede im Verdienst von Selbständigen und abhängig Beschäftigten und die Neigung der Selbständigen ihre Einkünfte zu niedrig auszuweisen eine bedeutende Rolle für den gemessenen Verdienstunterschied spielen. Wie hoch diese genau ist, ist eine interessante Forschungsfrage für zukünftige Arbeiten.

Einschränkend ist anzumerken, dass ich bei meiner Analyse nur auf einen Querschnittsdatensatz zurückgreifen konnte. Ich kann deshalb nicht ausschließen, dass meine Ergebnisse durch die Nichtberücksichtigung unbeobachteter Heterogenität verzerrt sein könnten. Zwar bietet die BIBB/BAuA Erwerbstätigenbefragung 2012 vergleichsweise detaillierte Informationen zu den Fähigkeiten der Befragten. Dennoch könnten Arbeitsbedingungen möglicherweise mehr erklären, wenn es gelänge, unbeobachtete Unterschiede in den Fähigkeiten noch besser zu berücksichtigen. Mir sind jedoch keine (deutschen) Panel-Datensätze bekannt, die die erforderlichen detaillierten Informationen zu den Arbeitsbedingungen sowohl für abhängig Beschäftigte als auch für Selbständige beinhalten.

Notes

One interesting study questioning these findings is Hanglberger and Merz (2011), who show with German panel data that the self-employment satisfaction premium disappears once one accounts for anticipation and adaption effects.

Besides that there seems to be no study examining the role of flexibility, variety, and autonomy for the earnings differential between self-employment and paid employment, there also does not seem to be a study investigating directly the link between such working conditions and the earnings of the self-employed per se. Extant evidence focuses exclusively on the link between working conditions and satisfaction. For paid employees, on the other hand, there are plenty of studies considering compensating wage differentials for certain working conditions (for recent evidence, see, e.g., Fernández and Nordman 2009 and the literature cited therein; specifically for Germany, one may start with Villanueva 2007).

The German SOEP collects information on working conditions only very sporadically (identical questions on some working conditions were asked recently in waves 2011 and 2006, and certain other working conditions were queried lastly in waves 2001 and 1995).

Although not exactly the same, self-employment and entrepreneurship will essentially be used synonymously throughout this paper. For an extensive discussion on the alternative ways of defining and measuring entrepreneurship the reader may want to look into Iversen et al. (2008).

To get a better sense of the measurement of earnings used here, I also provide the respective earnings figures calculated from the German SOEP in Sect. 3. In that survey, respondents were asked: “What was the amount of your labor earnings in the last month? If possible, please state both: The gross earnings, i.e., wage or salary before deduction of taxes and social security. The net earnings, i.e., the amount after deduction of taxes and contributions to pension, unemployment, and sickness insurance.” Additionally, there was a note: “If you are self-employed: Please estimate your monthly profit before and after taxes.”

In the BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey 2012, 29 % of the self-employed did not report earnings, whereas this was only the case for 19 % of the paid employees.

Specifically, on top of the gross wage, employers in Germany have to pay mandatory social security contributions amounting to about 20 % of the gross wage (the so called “Arbeitgeberbeitrag zur Sozialversicherung”).

Using binary variables for the working conditions instead of variables with three and four categories, respectively, simplifies the interpretation of results. My insights do not change when using all available variation by including working conditions variables with three and four categories, respectively, in a robustness check.

The respective earnings figures based on own calculations with the 2012 wave of the German SOEP are uniformly lower than those obtained with the BIBB/BAuA Employment Survey 2012, but show a similar pattern. Self-employed men report higher gross earnings than male paid employees both on a monthly and on an hourly basis (€ 3860 (Std. dev. 4316) vs. € 3017 (Std. dev. 1988) and € 21.1 (Std. dev. 24.2) vs. € 16.6 (Std. dev. 9.9), respectively), and female self-employed also report higher monthly and hourly gross earnings than their regularly employed counterparts (€ 2279 (Std. dev. 2555) vs € 1860 (Std. dev. 1654) and € 18.1 (Std. dev. 23.2) vs. € 13.8 (Std. dev. 29.8), respectively).

The multivariate analyses in Sect. 4 show that the self-employed on average indeed report lower earnings than what they are expected to earn in paid employment. Other results for Germany, all based on German SOEP data, are ambiguous: McManus (2000), using the waves 1984 to 1995, does not find statistically significant earnings differences between the self-employed and paid employees. Martin (2013), utilizing the waves 1984 to 2008, concludes that entrepreneurship does pay in Germany, at least for men. Braakmann (2007), who analyzes the waves 2000 to 2005, finds that those self-employed below the 40 % quantile of the earnings distribution would earn considerably higher earnings were they working in paid employment. Using the waves 1984 to 2005, Fossen (2012) shows that the self-employed would earn higher gross earnings in paid employment in the first 15 years of self-employment. Net earnings, however, would be higher in self-employment almost from the beginning for men, but women would also have to endure lower net earnings for a long period of time. In contrast, Constant (2009) finds that self-employment also pays for women, when analyzing SOEP data from 2002. Finally, the results of Block et al. (2011) and Constant and Shachmurove (2006), utilizing the waves 1984 to 2004 and 2000, respectively, indicate that self-employment seems to be a particularly profitable option for immigrants. These analyses do not correct for potential mis-measurement of earnings though.

Given this rich information on job characteristics, I do not additionally include a catch-all indicator of job characteristics like, for instance, dummies capturing professional fields. This seems especially appropriate since I want to separate the effects of certain working conditions and other job characteristics that are usually both captured by some industry or professional field dummies that serve as control variables. That said, my insights do not change when I do include 12 occupational area dummies (results available on request).

Unfortunately, even if panel data with similarly detailed information on working conditions were available, applying standard Fixed Effects regressions to control for unobserved heterogeneity would not solve the problem, because the self-selection of job changers leads to spurious correlation between wages and working conditions (see Solon 1988; Villanueva 2007).

If no good instrument for selection is available, subsample OLS may in fact be more robust than “correcting” for selection (cf. Puhani 2000).

This may be different for persons working in their parents’ businesses, but helping family members have been excluded from the sample.

At the same time, the self-employment status of a parent is not statistically significant if included in the wage regressions of paid employees, and age (linear and squared) is only statistically significant in the wage regression for women (at the 0.1 % level).

Neuman and Oaxaca (2004) discuss four different possibilities how to decompose earnings gaps in the presence of selection terms and conclude that “[t]he choice of which selectivity corrected decomposition to use is largely judgmental” (p. 8). While my approach corresponds to alternatives two and four (Eqs. 12 and 14), respectively, in their paper, it is important to note that it makes no difference at all which decomposition I use when it comes to the contribution of working conditions to the self-/paid employment earnings gap as the estimation of is identical in all four cases. What differs between the alternatives is the size of the total explained gap depending on how one apportions the selection terms to the explained or unexplained part.

The results of the respective selectivity-corrected earnings regressions for self-employed and paid employees separately are provided in Appendix Table 5.

The “unexplained” differences in earnings presumably reflect the different measurement of self-employment earnings and wages (and also some other unobserved factors). It is kind of puzzling that the “unexplained” earnings differential is so much higher for women than for men. However, this finding corresponds well with extant evidence showing that the returns to entrepreneurship are considerably lower for women than for men in Germany (cf., e.g., Martin 2013; Fossen 2012), and that the relative earnings of women compared to men are considerably lower in self-employment than in paid employment (e.g., Lechmann and Schnabel 2012).

The RIF of the median is RIF(y; median) = median + (0.5−1{y ≤ median})/(f y (median)), y being earnings, fy(.) being the respective density function and 1{.} being an indicator function. Basically, the RIF of the median for a given group is a dummy variable indicating whether an observation is below or above the median and hence gives the proportion of individuals being below or above a certain earnings level. By dividing by the density, one can invert proportions back to quantiles. Adding the median (thereby “recentering” the influence function) ensures that the expected value of the RIF equals the median (since the expected value of the second summand equals zero). For a detailed review of this method, see Fortin et al. (2011).

References

Åstebro, T.: The returns to entrepreneurship. In: Cumming, D. (ed.) The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurial Finance, pp. 45–108. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2012)

Åstebro, T., Chen, J.: The entrepreneurial earnings puzzle: mismeasurement or real? J. Bus. Venturing. 29, 88–105 (2014)

Åstebro, T., Thompson P.: Entrepreneurs, Jacks of all Trades or Hobos? Res. Pol. 40, 637–649 (2011)

Benz, M.: Entrepreneurship as a non-profit-seeking activity. Intern. Entrep. Manag. J. 5, 23–44 (2009)

Benz, M., Frey, B.S.: The value of doing what you like: evidence from the self-employed in 23 countries. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 68, 445–455 (2008)

Blanchflower, D.G., Oswald, A.J.: What makes an entrepreneur? J. Lab. Econ. 16, 26–60 (1998)

Blanchflower, D.G.: Self-employment: more may not be better. Swedish Econ. Pol. Rev. 11, 15–73 (2004)

Blinder, A.S.: Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J. Human Res. 8, 436–455 (1973)

Block, J., Sandner, P., Wagner, M.: Selbständigkeit von Ausländern in Deutschland. Soziale Welt 62, 7–23 (2011)

Borjas, G.J.: Labor Economics. McGraw-Hill, New York (2013)

Braakmann, N.: Differences in the earnings distribution of self- and dependent employed German men—evidence from a quantile regression decomposition analysis. University of Lüneburg Working Paper Series in Economics 55 (2007)

Constant, A.F.: Businesswomen in Germany and their performance by ethnicity. Int. J. Manpower. 30, 145–162 (2009)

Constant, A.F., Shachmurove Y.: Entrepreneurial ventures and wage differentials between Germans and immigrants. Int. J. Manpower. 27, 208–229 (2006)

Croson, D.C., Minniti, M.: Slipping the surly bonds: the value of autonomy in self-employment. J. Econ. Psych. 33, 355–365 (2012)

de Wit, G.: Models of self-employment in a competitive market. J. Econ. Surveys. 7, 367–397 (1993)

Engström, P., Holmlund, B.: Tax evasion and self-employment in a high-tax country: evidence from Sweden. Appl. Econ. 41, 2419–2430 (2009)

Faulenbach, N., Kay, R., Werner, A.: Die Opportunitätskosten der sozialen Absicherung für Selbstständige in Deutschland: Simulationsrechnungen für ausgewählte Fallgruppen. IfM-Materialien 177, Bonn (2007)

Fernández, R.M., Nordman, C.J.: Are there pecuniary compensations for working conditions? Lab. Econ. 16, 194–207 (2009)

Fortin, N., Lemieux, T., Firpo, S.: Decomposition methods in economics. In: Ashenfelter, O.C., Card, D. (eds.) Handbook of Labor Economics, vol. 4A, pp. 1–102. North-Holland, Amsterdam (2011)

Fossen, F.M.: Gender differences in entrepreneurial choice and risk aversion—a decomposition based on a microeconometric model. Appl. Econ. 44, 1795–1812 (2012)

Hall, A., Siefer, A., Tiemann, M.: BIBB/BAuA Employment survey of the working population on qualification and working conditions in Germany 2012, suf_3.0. Research Data Center at BIBB (ed.); GESIS Cologne (data access); Federal Institute of Vocational Education and Training, Bonn (2014). doi:10.7803/502.12.1.1.10

Hamilton, B.H.: Does entrepreneurship pay? An empirical analysis of the returns to self-employment. J. Pol. Econ. 108, 604–631 (2000)

Hanglberger, D., Merz, J.: Are self-employed really happier than employees? An approach modeling adaptation and anticipation effects to self-employment and general job changes. IZA Discussion Paper 5629, Bonn (2011)

Heckman, J.J.: Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica. 47, 153–161 (1979)

Hundley, G.: Why and when are the self-employed more satisfied with their work? Ind. Relat. 40, 293–316 (2001)

Hurst, E., Li, G., Pugsley, B.: Are household surveys like tax forms: Evidence from income underreporting of the self-employed. Rev. Econ. Stat. 96, 19–33 (2014)

Hyytinen, A., Ruuskanen, O.-P.: Time use of the self-employed. Kyklos. 60, 105–122 (2007)

Hyytinen, A., Ilmakunnas, P., Toivanen, O.: The return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle. Lab. Econ. 20, 57–67 (2013)

Iversen, J., Jørgensen, R., Malchow-Møller, N.: Defining and measuring entrepreneurship. Found. Trends Entrep. 4, 1–63 (2008)

Kawaguchi, D.: Self-employment rents: Evidence from job satisfaction scores. Hitotsubashi J. Econ. 49, 35–45 (2008)

Kihlstrom, R.E., Laffont, J.-J.: A general equilibrium entrepreneurial theory of firm formation based on risk aversion. J. Pol. Econ. 87, 719–748 (1979)

Knight, F.H.: Risk, uncertainty, and profit. Houghton Mifflin, Boston (1921)

Krichevskiy, D.: Three essays on entrepreneurial motivation, entry, exit and monetary rewards. FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations 519. http://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/519 (2011). Accessed 10 July 2014

Lange, T.: Job satisfaction and self-employment: autonomy or personality? Small Bus. Econ. 38, 165–177 (2012)

Lechmann, D.S.J., Schnabel, C.: Why is there a gender earnings gap in self-employment? A decomposition analysis with German data. IZA J. Europ. Lab. Stud. 1(6) (2012). doi:10.1186/2193-9012-1-6

Martin, J.: The impact on earnings when entering self-employment: evidence for Germany. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 537 (2013)

McManus, P.A.: Market, state, and the quality of new self-employment jobs among men in the U.S. and Western Germany. Soc. Forces. 78, 865–905 (2000)

Millán, J.M., Hessels, J., Thurik, R., Aguado, R.: Determinants of job satisfaction: a European comparison of self-employed and paid employees. Small Bus. Econ. 40, 651–670 (2013)

Moskowitz, T.J., Vissing-Jørgensen, A.: The returns to entrepreneurial investment: a private equity premium puzzle? Amer. Econ. Rev. 92, 745–778 (2002)

Neuman, S., Oaxaca, R.: Wage decompositions with selectivity‑corrected wage equations: a methodological note. J. Econ. Inequality. 2, 3–10 (2004)

Oaxaca, R.: Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int. Econ. Rev. 14, 693–709 (1973)

Parker, S.C.: The economics of entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2009)

Puhani, P.: The Heckman correction for sample selection and its critique’. J. Econ. Surveys. 14, 53–68 (2000)

Rohrbach-Schmidt, D., Hall, A.: BIBB/BAuA-Erwerbstätigenbefragung 2012. BIBB-FDZ Daten- und Methodenbericht 1/2013, Bonn (2013)

Rosen, S.: The theory of equalizing differences. In: Ashenfelter, O.C., Layard, R. (eds.) Handbook of Labor Economics, vol. 1, pp. 641–692. North-Holland, Amsterdam (1986)

Sarada, F.N.O.: The unobserved returns to entrepreneurship. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/04b3p1p0 (2010). Accessed 10 July 2014

Schjoedt, L.: Entrepreneurial job characteristics: an examination of their effect on entrepreneurial satisfaction. Entrep. Theory Pract. 33, 619–644 (2009)

Solon, G.: Self-selection bias in longitudinal estimation of wage gaps. Econ. Letters. 28, 285–290 (1988)

Villanueva, E.: Estimating compensating wage differentials using voluntary job changes: evidence from Germany. Ind. Lab. Relat. Rev. 60, 544–561 (2007)

Wooldridge, J.M.: Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press, Cambridge (2010)

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for very helpful suggestions by Claus Schnabel. For further valuable comments, I thank Nicole Gürtzgen, Sven Jung, two anonymous referees of this journal, and participants in seminars at the University of Erlangen-Nürnberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lechmann, D. Can working conditions explain the return-to-entrepreneurship puzzle?. J Labour Market Res 48, 271–286 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12651-015-0172-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12651-015-0172-y