Abstract

This study examined the prevalence of physical and relational victimization and its relationship with self reported depressive symptoms and emotional and behavioral problems. A sample of 376 adolescents studying in 9th to 12th class (Mean age = 14.82 years, SD = 96) from Government and Private Schools of a North Indian city participated in the study. They completed measures of experiences with bullying and victimization, depression, and emotional and behavior problems. Three groups of students were compared: victims of physical bullying, victims of relational bullying, and those who were neither victims nor perpetrators of bullying. Nearly one-fourth of the students were victims of bullying. Physical bullying was reported by 8 %, relational bullying by 12 %, and 4 % reported being victims of both physical and relational bullying. Boys reported more direct victimization while girls were more likely to be victims of relational bullying. Victimization status was significantly related to self reported depression (F = 9.48, P = 000) and total difficulties score (F = 17.38, P = 000). Victims of relational aggression had relatively higher depression scores and conduct problems, while physically victimized adolescents reported more peer problems. Given the concurrent psychosocial adjustment problems associated with victimization, there is need for designing preventive and intervention programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years considerable attention has been paid to school violence, particularly bullying and victimization. Bullying is considered a distinct type of aggression, repeated over a time period, characterized by systematic abuse of power intended to harm, cause distress or control another (Olweus 1993). Peer victimization is one of the most common problems that students experience during their school years and is wide spread and pervasive in several countries (Card and Hodges 2008; Craig et al. 2009; Hanish and Guerra 2000; Wang et al. 2009). Several authors have suggested the need to distinguish between different forms of victimization (e.g., Cole et al. 2010; Storch et al. 2005). Physical victimization is the experience of being directly harassed by other schoolmates through physical acts (e.g., kicking, pushing) which cause bodily harm. Indirect or relational bullying are nonphysical behaviors that are intended to damage peer relationships and social status or reputation, through behaviors such as threats or actual social exclusion, spreading malicious rumors or gossip (Archer and Coyne 2005; Crick and Grotpeter 1995). Indirect bullying behaviors are subtle and covert forms of attack which do not appear aggressive and sometimes may be hidden behind a façade of friendship, thereby making it difficult to detect (Archer and Coyne 2005).

Research examining victimization has documented that frequently victimized students, compared to their non-victimized peers, report more physical health problems (Gini and Pozzoli 2013), emotional and psychological problems (Reijntjes et al. 2010), reduced academic achievement (Storm et al. 2013), loneliness, depression (Storch and Masia-Warner 2004), low self esteem (Prinstein et al. 2001); school avoidance (Hutzell and Payne 2012), heightened risk for suicide and suicide attempts (Turner et al. 2012); and externalizing behaviors including aggression, delinquency, and substance use (Prinstein et al. 2001; Sullivan et al. 2006). For example, Cook et al. (2010) conducted a meta analysis of 153 studies to identify the common and unique characteristics of victims of bullying. According to the authors, a typical victim is one who has internalizing symptoms; engages in externalizing behavior, is not accepted by peers, lacks social problem solving skills and belongs to an adverse home and school environment.

Most of the research on consequences of different forms of victimization and emotional and behavioral functioning has been limited by its exclusive focus on developed countries, and rarely been studied in non-western societies in general, and India in particular (Bowker et al. 2011; Malhi et al. 2014). The issue is particularly relevant given the salience adolescents place on friendships, peer relationships and support during this developmental stage (Waldrip et al. 2008). It has been suggested in the literature that relational aggression may be more damaging in Asian countries because of their cultural orientation which greatly values cooperation, interdependence, and personal relationships in contrast to western societies which place more emphasis on individuality, social initiative, and independence (Bowker et al. 2011; Chen and French 2008). Indeed, culturally guided social interaction including evaluations and responses greatly influence children’s social behaviors and peer relationships. Therefore, there is need to conduct studies in the majority world as this would help in improving our understanding of interpersonal relationships and assist in designing culturally sensitive intervention strategies to tackle bullying. Keeping this in mind, the present study aimed to study the prevalence of physical and relational bullying; and to examine the relationship between victimization and self reported depressive symptoms and emotional and behavioral problems in a sample of adolescents.

Methody

Participants

This study was part of a larger project which examined the academic achievement correlates of adolescents. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the institute. Participants were 376 adolescents (Mean = 15.69 years, SD = 1.36; Boys = 53.5 %) from 9th to 12th grades studying in Private and Government schools of Chandigarh. A trained research assistant described the study to potential participants and all assessments and interviews were conducted individually in a quiet, private room within the school thereby ensuring confidentiality. Socio-economic status for the sample was predominantly middle class (63.6 %) and one fourth (24 %) were from low, and only 7 % were from high socio-economic status families. Only a minority of the adolescents came from single-parent families (5.3 %).

Measures

Physical victimization was measured by one question “have you been hit, kicked, pushed, or shoved around by another student at school? Relational bullying was measured by the question “have other students told lies or spread false rumors about you and tried to make others dislike you?” The student was classified as a victim of direct bullying if the respondent chose “sometimes,” “usually/always” on the physical victimization question and was classified as a victim of indirect or relational bullying if the respondent chose “sometimes,” “usually/always” on the relational victimization question. Students who were neither perpetrators of bullying nor victims were classified as controls. Victims were asked additional questions related to the place of bullying; number of children who bullied them; who were the children who bullied them; whether they had reported it; and whether the school or parents had intervened. Students who were neither victimized nor were perpetrators of victimization served as controls.

Depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, Radloff 1977) was used to measure self reported depression. The 20 items scale comprises six scales measuring six dimensions of depression including depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disturbance. Responses are scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). Total scores range from 0 to 60 and higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. A score of 16 or higher is used as the cut-off point for high depressive symptoms.

Emotional and Behavioral difficulties: The Youth self report measure (11–17 years) of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire was used to assess emotional and behavioral difficulties (Goodman 1997). It consists of 25 statements which are categorized into five subscales: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and pro-social behavior. Students have to respond on a three point scale “not true”, “somewhat true” or “certainly true” on the basis of their behavior in last 6 months. A total difficulties behavior score is computed by combining all scales except the pro-social behavior scale.

Socioeconomic status: The revised Kuppuswamy socio-economic status scale (Kumar et al. 2007) was used to assess the socio-economic status of the family.

Results

The overall prevalence of any kind of victimization was 23.7 %. Out of the 376 students, 8 % were victims of physical bullying and had been physically assaulted in schools several times in a month. Relational victimization including having one’s relationships damaged by rumor spreading and slandering, and social isolating was reported by 11.7 % of the students. Only a small minority of adolescents (4 %) were victims of both physical and relational bullying. Most of the physical and relational victimization took place at schools in the playgrounds (59.1 % and 37 %, respectively), in classrooms when the teacher was not present (50 % and 45.2 %, respectively) and during the recess period (44.1 % and 50 %, respectively). A large majority of the victimized pupils (62.2 %) did not report the bullying to a person in authority. Among those students who did report the victimization, most informed their parents (27.1 %) or teachers (16.1 %). Victims of physical bullying (16.7 %) as compared to adolescents of relational bullying (2.3 %) were significantly more likely to miss schools (χ 2 = 20.64, P = .000). The average duration of physical and relational victimization was 1.24 years (SD = 1.19) and 1.17 years (SD = 1.24), respectively.

Table 1 presents comparison of the three groups: victims of physical bullying, victims of relational bullying, and controls by sex, age, and socio-economic status. Chi-square test showed an effect of gender on group membership. Boys reported more direct victimization and were 13.18 times as likely as girls to be victims of physical bullying while girls were 1.55 times more likely to be victims of relational bullying (=24.15, P = .000) (Fig. 1). Significant differences emerged between groups with respect to socioeconomic status (χ 2 = 18.94, P = 001). Students from lower socio-economic status were more likely to be victims of physical victimization, while victims of relational bullying status were more likely to belong to higher socio-economic. Age trends in bullying were also examined. Physical bullying peaked for students aged 14 to 16 years and then declined, whereas relational bullying increased with age and older children were 4 times more likely to be victims of relational bullying than younger children (χ 2 = 19.74, P = 001). Indeed, one-fourth of older adolescents reported being victims of relational bullying.

There was a significant relationship between victimization status and depression (F = 9.48, P = 000). Victims of relational bullying had the highest depression scores as compared to other groups, however, the difference between relational (M = 17.89, SD = 9.63) and physical bullying victims (M = 13.60, SD = 9.71) did not reach significance level. In addition, a significantly higher proportion of relational bullying victims (52.3 %) as compared to physical bullying victims (30 %) had depression scores above the cutoff score and hence were at a higher risk for depression (χ 2 = 11.78, P = 003). Although girls had higher depression scores, the difference between boys and girls was not statistically significant.

Table 2 present the results for strength and difficulties scores by victimization status. Compared with control students, victims had significantly higher risk for conduct problems (F = 13.47, P = 000), hyperactivity (F = 15.23, P = 000) and total difficulties score (F = 17.19, P = 000) as compared to controls. Victims of relational bullying had significantly (P = 047) higher conduct problems than victims of physical bullying. Interestingly, only physical bullying victims reported significantly higher peer problems (F = 4.09, P = 018) than control students, and victims of relational aggression did not differ from the controls on peer difficulties. No significant differences on any of the other sub-scale scores of SDQ were found between victims of physical and relational bullying.

Discussion

The present study examined the prevalence of victimization and the association between type of victimization and self reported depression and emotional and behavior problems among school going adolescents. The prevalence of victimization among Indian adolescents was substantial and nearly one-fourth were found to be victimized by their peers. Several research studies document that approximately 10 to 20 % of students in schools, are targets of regular and chronic victimization by their classmates (Card and Hodges 2008; Craig et al. 2009; Hanish and Guerra 2000; Malhi et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2009). Higher rates for victimization are reported (30 % to 60 %) if students are asked if they have been victimized during the current school year (Nansel et al. 2001; Smokowski et al. 2013). However, there is considerable variability among countries in the prevalence of bullying. In an international cross-sectional self-report survey of 11 to 15 year olds from 40 countries, the percentage of students who reported being bullied ranged from a low of 8 % to a high of 45 % in other countries (Craig et al. 2009). In line with previous research, relational victimization was somewhat more prevalent than physical bullying (Rosen et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2009).

Since most of the victimization took place in the playgrounds, classrooms, and lunch breaks when children were left unsupervised, our findings suggest the need for more effective supervision in bully prone areas of schools. In this context, it may be noted that Olweus (1993) found that the level of bullying was lower in schools where there were relatively more teachers present during recess and other breaks. Despite the high prevalence of bullying, surprisingly majority of the bullied students did not report their victimization to the school personnel or to their parents. Possibly, victimized students have little faith in school authorities or their parents to effectively stop the bullying. Alternatively, they may fear escalation of their victimization subsequent to their reporting it (Newman and Murray 2005). It is also possible that Indian schools consider bullying normative and have greater tolerance for it and this discourages most students from reporting it. Hence, there is a need for schools to create a safe environment in which students can report their victimization without fear of retribution (Fekkes et al. 2005).

Prevalence rates varied by demographic and socio-economic characteristics

Boys were significantly more likely to be victims of physical bullying, whereas relational aggression occurred more frequently in girls than boys. Previous research has consistently found boys to be at greater risk for physical forms of victimization, whereas girls are more likely to experience relational forms of victimization, particularly during the adolescent years (Archer 2004; Björkqvist et al. 1992; Carbone-Lopez et al. 2010; Sinclair et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2009). Moreover, older adolescents were more likely to be victims of relational bullying while younger adolescents were more likely to be victims of physical aggression. These findings are consistent with previous studies documenting that physical violence is more prevalent in younger ages and use of indirect aggression increases with age. Younger children are more likely to be physically bullied because they lack the physical and social skills which can protect them from direct aggressive attacks and are therefore more vulnerable than older and probable stronger peers (Hanish and Guerra 2000). On the other hand, the decrease in physical violence coincides with an increase in relational violence during the middle adolescence probably as covert aggression requires social and verbal skills, which develop with age (Björkqvist et al. 1992). In addition, students from lower socio-economic homes were more likely to be victims of physical victimization, while students from higher socio-economic status homes were more likely to be victims of relational bullying. Previous studies have documented that students from socioeconomically disadvantaged families have higher prevalence of victimization (Due et al. 2009; Von Rueden et al. 2006). Possibly, bullies tend to physically target students who have attributes that are socially devalued such as being poor, while children who are from socially advantaged homes tend to be the targets of indirect and covert forms of aggression.

Consistent with findings from Western studies, victims of relational bullying as compared to victims of physical bullying and controls reported significantly higher levels of depression (Cole et al. 2010; Ttofi et al. 2011; Kawabata et al. 2010). Evidence indicates that in contrast to physical victimization, it is relational forms of victimization which are more strongly associated with increased internalizing problems (Cole et al. 2010; Woods et al. 2009; ZimmerGembeck and Pronk 2012). For example, Woods et al. (2009) reported significantly more feelings of loneliness and emotional problems among targets of relational bullying than non-victims, whereas students who experienced physical victimization did not differ from non-victims. It has been suggested that for adolescents, peer appraisals are extremely salient in the development of their self-concept and self-worth, hence the degrading nature of peer victimization may lead to feelings of low self worth and increase their vulnerability to depression (Hanish and Guerra 2000; Reijntjes et al. 2010; Storch and Ledley 2005; Turner et al. 2012). Moreover, evidence suggests that depression in adolescents may function as both an antecedent and a consequence of peer victimization and these reciprocal influences may contribute towards a high stability of peer victimization (Reijntjes et al. 2010). In view of these findings, it is important that school counselors encourage victimized individuals to make friends, since depressive symptoms among rejected youth tend to decline as they make new friends (Bukowski et al. 2010).

Although evidence indicates that having friends can protect adolescents from victimization (Sainio et al. 2011) it is often hard for victimized youth to find and sustain protective friendships as peers avoid befriending victims, as they fear becoming rejected or victimized themselves (Boulton 2013; Sentse et al. 2013). In this context, it is noteworthy that physically victimized adolescents reported more peer problems than the victims of relational aggression who in turn reported no more peer problems than the controls. Possibly, since victims of physical bullying are identifiable by their peers due to the overt nature of the aggressive acts they may be more likely to be avoided and rejected by peers. This may result in physically victimized youth to experience more difficulty in finding friends as compared to victims of relational aggression (Sentse et al. 2013). These findings extend prior research by emphasizing a potential link between peer victimization and internalizing problems among urban Indian high school youth. Moreover, physical aggression victims also reported school avoidance. Understandably, when students are targets of physical violence, they are more likely to perceive school as an unsafe place and this increases absenteeism (Hutzell and Payne 2012).

Interestingly, victims of relational bullying reported significantly higher conduct problems than victims of physical bullying. There is a growing literature suggesting that both perpetration of bullying and victimization are related to increased involvement in externalizing problems such as violence, substance abuse, delinquency, peer aggression, and weapon-carrying (Higgins et al. 2012; Reijntjes et al. 2011; Sullivan et al. 2006). Evidence indicates that adolescents who are rejected and victimized are more likely to associate with deviant peers and this contribute to the development of antisocial behavior and substance use (Rusby et al. 2005). It appears that relational aggression victims may find greater peer acceptance by displaying more proactive aggressive behavior themselves. The association of bullying with conduct difficulties, particularly among victims of relational aggression is an important finding as it suggests the need for promoting effective anti-bullying intervention programs as a critical early anti-delinquency intervention.

Few limitations of the study must be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not clarify whether peer victimization is a cause or a consequence of conduct and emotional problems. It remains possible that adolescents with greater internalizing and externalizing difficulties are likely targets for victimization. Indeed, several longitudinal studies have found support for this. It is also possible that psychological problems and victimization may be both due to other independent variables. Longitudinal research is needed to further examine these relations. Secondly, the study used only self report data and the results may partly be due to shared method variance. Nevertheless, the study has several strengths. It is one of the few studies conducted in India which has distinguished different types of victimization and examined its relationship with demographic and socio-economic variables and emotional and behavioral problems.

In sum, a significant proportion of Indian school going students are victims of physical and relational aggression, and bullying is not confined to only western cultures. Despite aggression being a major problem in school going youth, it is infrequently reported or addressed by school personnel. Since bullying can have both short- and long- term physical and mental health consequences, there is an imperative need to increase awareness among pediatricians, mental health professional, and school personnel. There is also a critical need to explore the types of community, family, and individual-level factors that protect youth from involvement in bullying and promote resilience among victims of school aggression.

References

Archer, J. (2004). Sex differences in aggression in real world settings: a meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology, 8(4), 291–322.

Archer, J., & Coyne, S. M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 212–230.

Björkqvist, K., Lagerspetz, K. M. J., & Kaukiainen, A. (1992). Do girls manipulate and boys fight? developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 18(2), 117–127.

Boulton, M. (2013). The effects of victim of bullying reputation on adolescents’ choice of friends: mediation by fear of becoming a victim of bullying, moderation by victim status, and implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 114(1), 146–160.

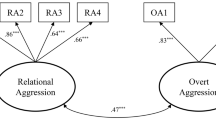

Bowker, J. C., Ostrov, J. M., & Raja, R. (2011). Relational and overt aggression in urban India: associations with peer relations and best friends’ aggression. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 36(2), 107–116.

Bukowski, W. M., Laursen, B., & Hoza, B. (2010). The snowball effect: friendship moderates escalations in depressed affect among avoidant and excluded children. Development and Psychopathology, 22(4), 749–757.

Carbone-Lopez, K., Esbensen, F.-A., & Brick, B. T. (2010). Correlates and consequences of peer victimization: gender differences in direct and indirect forms of bullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 8(4), 332–350.

Card, N. A., & Hodges, E. V. E. (2008). Peer victimization among schoolchildren: correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(4), 451–461.

Chen, X., & French, D. (2008). Children’s social competence in cultural context. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 591–616.

Cole, D. A., Maxwell, M. A., Dukewich, T. L., & Yosick, R. (2010). Targeted peer victimization and the construction of positive and negative self-cognitions: Connections to depressive symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39(3), 421–445.

Cook, C. R., Williams, K. R., & Guerra, N. G. (2010). Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: a meta-analytic investigation. School Psychology Quarterly, 25(2), 65–83.

Craig, W., Harel-Fisch, Y., Fogel-Grinvald, H., Dostaler, S., Hetland, J., Simons-Morton, B., et al. (2009). A cross-national profile of bullying and victimization among adolescents in 40 countries. International Journal of Public Health, 54(2), 216–224.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender and social psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722.

Due, P., Merlo, J., Harel-Fisch, Y., Damsgaard, M. T., Holstein, B. E., Hetland, J., et al. (2009). Socioeconomic inequality in exposure to bullying during adolescence: a comparative, cross-sectional, multilevel study in 35 countries. American Journal of Public Health, 99(5), 907–914.

Fekkes, M., Pijpers, F. I. M., & Verloove-Vanhorick, S. P. (2005). Bullying: Who does what, when and where? involvement of children, teachers and parents in bullying behavior. Health Education Research Theory and Practice, 20(1), 81–91.

Gini, G., & Pozzoli, T. (2013). Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132(4), 720–729.

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586.

Hanish, L. D., & Guerra, N. G. (2000). Predictors of peer victimization among urban youth. Social Development, 9(4), 521–543.

Higgins, G. E., Khey, D. N., Dawson-Edwards, C., & Marcum, C. D. (2012). Examining the link between being a victim of bullying and delinquency trajectories among an African American sample. International Criminal Justice Review, 22(2), 110–122.

Hutzell, K. L., & Payne, A. A. (2012). The impact of bullying victimization on school avoidance. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 10(4), 370–385.

Kawabata, Y., Crick, N. R., & Hamaguchi, Y. (2010). The role of culture in relational aggression: associations with social-psychological adjustment problems in Japanese and US school-aged children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34(4), 354–362.

Kumar, N., Shekhar, C., Kumar, P., & Kundu, A. S. (2007). Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale- Updating for 2007. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 74, 1131–1132.

Malhi, P., Bharti, B., & Sidhu, M. (2014). Aggression in schools: Psychosocial outcomes of bullying among Indian adolescents. Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Mar 23. [Epub ahead of print].

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, K., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, J., Simon-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA, 285(16), 2094–2100.

Newman, R. S., & Murray, B. J. (2005). How students and teachers view the seriousness of peer harassment: when is it appropriate to seek help? Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 347–365.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: what We know and what We Can Do. Oxford: Blackwell.

Prinstein, M., Boergers, J., & Vernberg, E. (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(4), 479–491.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CED-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34(4), 244–252.

Reijntjes, A. H. A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., Boelen, P. A., van der Schoot, M., & Telch, M. J. (2011). Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 37(3), 215–222.

Rosen, L. H., Underwood, M. K., Gentsch, J. K., Rahdar, A., & Wharton, M. E. (2012). Adult recollections of peer victimization during middle school: forms and consequences. Journal of Applied Development Psychology, 33(6), 273–281.

Rusby, J. C., Forrester, K. K., Biglan, A., & Metzler, C. W. (2005). Relationships between peer harassment and adolescent problem behaviors. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(4), 453–477.

Sainio, M., Veenstra, R., Huitsing, G., & Salmivalli, C. (2011). Victims and their defenders: a dyadic approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(2), 144–151.

Sentse, M., Dijkstra, J. K., Salmivalli, C., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2013). The dynamics of friendships and victimization in adolescence: a longitudinal social network perspective. Aggressive Behavior, 39(3), 229–238.

Sinclair, K. R., Cole, D. A., Dukewich, T., Felton, J., Weitlauf, A. S., Maxwell, M. A., et al. (2012). Impact of physical and relational peer victimization on depressive cognitions in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(5), 570–583.

Smokowski PR, Cotter KL, Robertson C, & Guo S. Demographic, psychological, and school environment correlates of bullying victimization and school hassles in rural youth. Journal of Criminology, Volume 2013 (2013), Article ID 137583, 13 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/1375 DOI:10.1155/2013/137583 83.

Storch, E. A., & Ledley, D. R. (2005). Peer victimization and psychosocial adjustment in children: current knowledge and future directions. Clinical Pediatrics, 44(1), 29–38.

Storch, E. A., & Masia-Warner, C. (2004). The relationship of peer victimization to social anxiety and loneliness in adolescent females. Journal of Adolescence, 27(3), 351–362.

Storch, E. A., Masia-Warner, C., Crisp, H., & Klein, R. G. (2005). Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: a prospective study. Aggressive Behavior, 31(5), 437–452.

Storm, I. F., Thoresen, S., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Dyb, G. (2013). Violence, bullying and academic achievement: a study of 15-year-old adolescents and their school environment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 37(4), 243–251.

Sullivan, T. N., Farrell, A. D., & Kliewer, W. (2006). Peer victimization in early adolescence: association between physical and relational victimization and drug use, aggression, and delinquent behaviors among urban middle school students. Development and Psychopathology, 18(1), 119–137.

Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3(2), 63–73.

Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. (2012). Recent victimization exposure and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1149–1154.

Von Rueden, U., Gosch, A., Raimil, L., Bisegger, C., & Raven-Sieberer, U. (2006). The European KIDSCREEN group. Socioeconomic determinants of health related quality of life in childhood and adolescence: results from a European study. Journal of Epidemiological Community Health, 60(2), 130–135.

Waldrip, A. M., Malcolm, K. T., & Jensen-Campbell, L. A. (2008). With a little help from your friends: the importance of high-quality friendships on early adolescent adjustment. Social Development, 17(4), 832–852.

Wang, J., Iannotti, R. J., & Nansel, T. R. (2009). School bullying among adolescents in the United States: physical, verbal, relational, and cyber. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(4), 368–375.

Woods, S., Done, J., & Kalsi, H. (2009). Peer victimization and internalizing difficulties: the moderating role of friendship quality. Journal of Adolescence, 32(2), 293–308.

Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Pronk, R. E. (2012). Relation of depression and anxiety to self- and peer-reported relational aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 38(1), 16–30.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malhi, P., Bharti, B. & Sidhu, M. Peer Victimization Among Adolescents: Relational and Physical Aggression in Indian Schools. Psychol Stud 60, 77–83 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-014-0283-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-014-0283-5