Abstract

Objectives

Experimental evidence suggest that tea polyphenols have anti-depressant effect and tea consumption may reduce the risk and severity of depression. We investigated whether tea consumption was associated with changes in depressive symptoms over time among Asian older adults.

Design

Population-based prospective cohort study with mean 4 years of follow up.

Setting

Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study (SLAS) of community-living older persons.

Participants

3177 participants overall (mean age 67 years) and 3004 participants who were depression-free at baseline.

Measurements

Baseline tea consumption which include Chinese (black, oolong or green) tea or Western (mixed with milk) tea and change in Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) measure of depression. Incident depression was defined by GDS≥5, and GDS depression improvement or deterioration by GDS change of ≥4 points. Estimated odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (OR, 95%CI) were adjusted for baseline age, sex, ethnicity, education, housing type, single/divorced/widowed, living alone, physical and social activity, smoking, alcohol, number of comorbidities, MMSE, and baseline GDS level.

Results

Compared to non-tea drinkers, participants who consumed ≥3 cups of tea of all kinds were significantly less likely to have worsened GDS symptoms: OR=0.32, 95% CI=0.12, 0.84. Among baseline depression-free participants, the risk of incident GDS (≥5) depression was significantly lower (OR=0.34, 95%CI=0.13, 0.90) for daily consumption of all types of tea, and Chinese (black, oolong or green) tea (OR=0.46, 95%CI=0.21,0.99).

Conclusion

This study suggests that tea may prevent the worsening of existing depressive symptoms and the reduce the likelihood of developing threshold depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression leads the causes of disability worldwide, accounting for 5.7% of years lived with disability among older adults (1). Nearly 7% of older adults in the world are affected by depression (2). Experimental research has highlighted the potential anti-depressant effects of tea polyphenols and suggest that regular tea consumption may reduce the risk and severity of depression in humans (3–10). Epidemiological evidence for the benefits of tea consumption on mental health and wellbeing is however inconclusive (11, 12). Mixed findings are reported from about a dozen studies (13–22). The majority of studies are of cross-sectional design, and there is a paucity of prospective cohort studies that examine dose-response effect for different types of tea.

Tea leaves that are consumed as beverage worldwide are broadly of several types: black, oolong, or green, which result from different processing of tea leaves: fully fermented (black tea), semi-fermented (oolong tea), unfermented (green tea). Green tea is consumed by 20% of the world’s population, but is the primary beverage consumed in Asian countries (23). In Japan, 53% of adults consume green tea on a daily basis (24). In China, 47% of adults (64% of men and 28% of women) regularly drink tea of all types, of which 50% are green tea, 11 % are black or mixed tea, and the remaining are other teas (floral and blue tea) (25, 26). In Singapore, over half the population consume tea daily, most commonly traditional Chinese (black, oolong or green) tea (30%) without milk, or ‘Western’ (or ‘English’) mixed tea consumed with milk; less than 10% consume green tea. More commonly, a mix of different types of tea are consumed, rather than exclusively one type.

In this study, we analysed data from the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study (SLAS) and examined the association of tea consumption and changes in depressive symptoms observed over 3–5 (mean 4) years period of follow up. We examined the associations for five categories of tea consumption, (1) overall, (2) black or oolong tea, (3) green tea, (4) ‘Chinese’ tea (black, oolong or green tea), or (5) ‘Western’ mixed tea consumed with milk.

Method

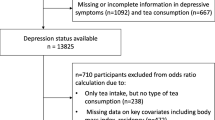

The Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study (SLAS) is an ongoing prospective cohort study of ageing and health transition initiated in 2003 with two successive waves of recruitment of participants in SLAS-1 (N=2804) in 2003–2004, and SLAS-2 (N=3270) in 2009–2011. Details of the SLAS cohort recruitment and data collection have been described in previous publications (27, 28). In brief, residents in the community, aged 55 and above were recruited from two geographically separated regions in Singapore, and provided baseline information on a range of personal, social, lifestyle and health-related behaviour, medical, physiological, psychological and cognitive data from extensive questionnaire-based interviews, clinical and performance-based testing. The study was approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board, and all participants signed informed consent. The participants were followed up at approximately 3–4 year intervals in the SLAS-1 cohort, and 3 to 5-years interval in the SLAS-2 cohort. The present study combined participants from both the SLAS-1 and SLAS-2 cohorts who were assessed at baseline and the first follow up visit (average 4 years after baseline). Complete data included baseline data on tea consumption, covariates and depression assessed by the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), and follow up depression outcome of 3177 participants with and without GDS depression at baseline, and 3004 participants who were free of GDS depression at baseline. See Flowchart of cohort recruitment, baseline and follow up assessments and data extraction.

Tea consumption. At baseline, tea consumption was assessed by reported habitual intake of common tea types using indigenous references and terms such as: ‘Ceylon/English’ tea (mixed blend of black tea usually consumed with milk), ‘Chinese tea’ referring to either Black or Oolong tea or ‘Green” tea. The reported frequency of consumption was categorized as: 0=Never or rarely; 1=Less than one cup/week; 2=one or more cups/week but less than one cup/day; 3=one to two cups/day; 4=three or more cups/day. A participant was classified as a non-tea drinker if the sum of the three scores was equal to zero. Given the small count in the category of ≥3 cups/day for specific tea types, the consumption level of specific tea type was analysed for three ordinal categories as: (1) non-drinker, (2) less than 1 cup daily, (3) ≥1 cups daily. For total consumption of any type of tea overall, consumption level was analysed as (1) none or <1cup daily (2) 1–2 cups daily and (3) ≥3 cups daily.

Depression

We assessed depression at baseline and follow up using the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) in English, Chinese and Malay translations, which has been previously validated in the Singaporean population to have high sensitivity and specificity for identifying DSM-IV diagnosis of major depressive disorder using cut-off of 4/5 or 5 more GDS symptoms (29).

We calculated the change in count of depressive symptoms from baseline in GDS score at follow up for each individual, and used the change score to determine improvement or deterioration of depression. Improvement or deterioration of depression was optimally defined as a decrease or increase of 4 or more depressive symptoms from baseline, as using 5 or more symptoms resulted in fewer counts for meaningful analysis.

Covariates

To control for the influence of confounding factors, baseline data of covariates included age (single years), sex, ethnicity (Chinese, Malay and Indian/Others), education (none or ≤6 years, 7–10 years, ≥11 years), housing type (low-end 1 or 2-room public housing, 3-room public housing, ≥4 room public housing or other high-end private housing), marital status (single/divorced/widowed versus married) living alone (yes versus no), smoking (non-smoker, past smoker, current smoker), daily alcohol (yes versus no), number of comorbidities (ranging from 0 to 12), physical activity and social activity score, and Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE). Physical activity was measured by the summed score of frequency of participation (0=never or <once a month, l=sometimes once per month but less than once a week, 2=often, once a week or more) in four categories of moderate to vigorous physical activity (brisk walking, other light to moderate exercise such as walking, dancing, bicycling, swimming, taichi, yoga, taiji, and active sports (tennis, badminton, golfing, etc) which are popular among older people. Social activity was similarly measured for participating in senior citizen club or social group activities, including card games, karaoke, line dancing, mahjong, karaoke, day excursion trips; religious services, sports or other organized public events. The number of comorbidities was assessed from self-report of a diagnosis and treatment for 18 specific chronic diseases and others. The English, Chinse and Malay translated and modified versions of the MMSE which was validated in a previous study was used to assess global cognition (30).

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS statistical package (version 25). We used analysis of variance for continuous data and chi-squared analyses for categorical data for comparisons of five categories of tea consumption: (1) overall, (2) black or oolong tea, (3) green tea, (4) ‘Chinese’ tea (black, oolong or green tea), or (5) ‘Western’ mixed tea consumed with milk. In the total cohort (N=3177), we compared the estimated mean GDS change scores among tea consumption groups using generalized linear mixed model for repeated measures, while adjusting for age, sex, ethnicity, education, housing type, single/divorced/widowed, living alone, physical activity score, smoking, alcohol, number of comorbidities, MMSE, and baseline GDS score, and Bonferroni-adjusted p-values to assess statistical significance. We compared the proportions of those who showed improved depression and worsened depression by tea consumption categories, and used logistic regression to estimate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) of association of tea consumption with the odds of improved depression or worsened depression, adjusted for the same demographic, economic deprivation, social isolation, lifestyle behaviour, and health variables. Among cohort participants (N=3004) who were free of depression at baseline, we estimated OR (95%CI) of association of tea consumption with incident depression (GDS>=5) observed at follow-up.

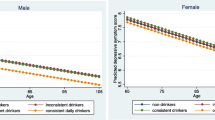

We conducted subgroup analyses to examine whether the observed associations differed by sex or age (<65 years old versus ≥65 years old). We performed several sets of sensitivity analyses for the full model to assess consistency of the effect estimates using different thresholds for the GDS with greater sensitivity or specificity to define improved or worsened depression and incident depression. We also tested our results based on the full sample after multiple imputation for missing data.

Results

Participants with available depression data who were followed up, compared to those were not followed up did not differ significantly on baseline GDS. However, they were significantly younger in age, more likely to be women, of Chinese ethnicity, better educated, and better housed; they were less likely to be single, divorced or widowed, living alone, or smokers but more likely to be daily alcohol drinkers; they were more physically and socially active, had fewer numbers of chronic medical conditions, and gave higher MMSE scores, and were more likely to be tea drinkers. (Supplementary Table 1)

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the followed-up study participants by their levels of total tea consumption. Tea drinkers compared to non-tea drinkers were significantly younger in age, more likely to be men, ethnically Chinese, have more years of education, have better housing situation, less likely to be single, divorced or widowed, more physically and socially active, and have higher MMSE cognitive scores.

The tea consumption groups did not differ significantly on the prevalence of GDS depression at baseline. At follow up, tea drinkers compared to non-tea drinkers (of all types and by different tea types) showed significantly lower prevalence of GDS depression. GDS depression symptoms in the whole cohort showed a reduction from baseline to follow up. The overall mean decline of −0.42 (SD of 2.13) symptoms did not differ significantly by tea consumption groups, but the proportions of those whose GDS scores worsened by 4 or more points were significantly less among tea drinkers than non-tea drinkers.

Table 2 shows the differences in estimated GDS changes by tea consumption groups adjusted for baseline age, sex, ethnicity, education, housing type, single/divorced/widowed, living alone, physical activity score, social activity score, smoking, alcohol, number of comorbidities, MMSE, and baseline GDS level. Participants who consumed 3 or more cups of tea of all kinds showed significantly greater reduction of GDS symptoms than non-drinkers. The odds of worsened GDS depression was significantly less among those who consumed 3 or more cups of all types of tea (OR=0.32, 95% CI=0.12, 0.84) compared to non-tea drinkers. The differences by specific tea types after covariate adjustment showed the same trends but were not statistically significant.

Among participants who were free of GDS depression at baseline (N=3004), the risk of incident GDS (≥5) depression was significantly lower by 70% among participants who consumed 3 or more cups of tea of all kinds daily compared to non-drinkers (OR=0.34, 95%CI=0.13, 0.90). Table 3. The risk estimates for individual tea types showed the same trends of association and was statistically significant for consumption of Chinese (black or oolong or green) tea (OR=0.46, 95%CI=0.21, 0.99).

We observed no material differences in the effect estimates by sex or age in subgroup analyses. In sensitivity analysis, we varied cut-off values of the GDS (above and below 5) used to define worsened or improved depression and incident depression, repeated the analysis for the fully adjusted model and observed only modest alterations in the observed dose-effect relationships. We tested our results using full sample after multiple imputation and observed reasonably consistent effect estimates with the final model.

Discussion

This prospective cohort study showed that the consumption of tea was associated with lowered risk of developing threshold depression. In particular, tea did not appear to have the effect of improving existing depressive symptoms but may have the beneficial effect of preventing the worsening of existing depressive symptoms.

Collaborating evidence from experimental and some clinical studies support the benefit of tea consumption for mental health and wellbeing. In mice models, tea polyphenols especially green tea catechins, such as epigallocatechin gallate (ECCG) exert anti-inflammatory actions (3, 4) and lower depression (5, 6) by, among other mechanisms, inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (7). Clinical studies show that L-theanine, a unique component in green tea, ameliorate stress-related symptoms and depressive disorders (8, 9). Evidence from human electroencephalograph (EEG) studies show that L-theanine significantly increases activity in the alpha frequency band indicating mental relaxation (10).

Our study adds to a growing body of recent epidemiological reports supporting the anti-depressant effects of tea consumption in older people, particularly in Asian populations (13, 15, 16, 18–22). The dose-response association appears to support a threshold level for 3 or more cups of teadaily, and possibly as well for 1–2 cups daily, especially for green tea. Prior studies have variously investigated unspecified tea type, which included two reports of null association with depression (14, 17, 20, 21) or only one type (green tea) alone which both reported positive association with reduced depressive symptoms (18, 20). In two studies which investigated both green and black tea (16, 19) one study in rural North China reported lower odds of depressive symptoms for green and black tea (16), whereas the other study in Eastern China reported an inverse association of black tea and depression, but not for green tea (19). We investigated several types of tea simultaneously in this study, and observed that consumption of any or all types of tea was associated overall with less depression, and this appeared to be especially true for the consumption of Chinese tea (both black, oolong or green), while the consumption of Western mixed tea with milk appeared to be less strongly associated. This appears to be commensurate with the weak or null association reported in several studies of Western populations. Some studies suggest that the addition of milk may reduce the anti-oxidant activity of black tea, due to the interaction between tea polyphenols and milk proteins, such as between catechins and caseins (31, 32). Further studies are needed to elucidate these observations.

Our study finding has important implications for population-based preventive measures to promote and maintain the mental health and quality of life of older persons (33). The prevalence of sub-syndromal and syndromal depression in the population of older persons in Singapore is estimated at about 9.6% and 4.9% respectively (34). Significantly large numbers of older persons with subsyndromal depression therefore have depressive symptoms (equivalent to GDS depression score of ≥5) that put them at increased likelihood of being clinically diagnosed as major depression. Studies have shown that subsyndromal depression is just as detrimental to well-being as clinical depression, as it is associated also with increased functional impairment, poor quality of life, hospitalization and mortality (35–37). For consuming 3 or more cups of tea daily, the estimated effect size for reducing depressive symptoms is moderate-to-strong (Cohen’s D=1.30 and OR=0.32). The observed effects of tea consumption on reducing the severity of depressive symptoms are in the subclinical efficacy range, but at the population level, it translates to a potentially non-trivial impact in reducing the societal burden of disease in the general population.

Strengths and limitations. The large sample prospective cohort design and use of longitudinal data is a strength of this study. The specific characterization of types of tea consumption is useful, given that bioactive constituents which vary in different types of tea through diverse processing methods may be responsible for heterogeneous findings reported in the literature. However, the small counts by daily consumption of individual black/oolong or green tea still limits statistical power for risk estimation. Another limitation is the large attrition from loss to follow-up, due to deaths and loss of contact and refusals. Participants who were not reassessed at follow up, compared to those in the study, were characterized by their demographic, economic deprivation, social isolation, lifestyle behaviour, and physical health profile at baseline to be more vulnerable to depression. They also included significantly fewer tea drinkers. The observed incidence of depression from follow up was most likely under-estimated in the follow-up cohort overall. Thus the overall favourable lifestyle and health profile of this follow up cohort should be noted and limits the generalization of the findings to other populations.

Conclusion

This study suggests that tea may prevent the worsening of existing depressive symptoms and thus reduce the likelihood of developing threshold depression. Further prospective cohort and interventional studies should investigate the heterogeneous effects of different types and ways of tea consumption on promoting and maintaining mental wellbeing in diverse populations.

References

WHO, 2008. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update; Technical Report for Health Statistics and Information Systems. Geneva, Switzerland

WHO (2017. Mental Health of Older Adults. http://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults. Accessed 02 Jun 2018

Siddiqui IA, Afaq F, Adhami VM, Ahmad N, Mukhtar H. Antioxidants of the beverage tea in promotion of human health. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2004;6:571–582

Rothenberg DO, Zhang L. Mechanisms Underlying the Anti-Depressive Effects of Regular Tea Consumption. Nutrients 2019;11:1361. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11061361

Zhu WL, Shi HS, Wei YM, Wang SJ, Sun CY, Ding ZB, Lin L. Green tea polyphenols produce antidepressant-like effects in adult mice. Pharmacological research 2012;65:74–80

de la Garza AL, Garza-Cuellar MA, Silva-Hernandez IA, Cardenas-Perez RE, Reyes-Castro LA, Zambrano E, Gonzalez-Hernandez B, Garza-Ocanas L, Fuentes-Mera L, Camacho A. Maternal Flavonoids Intake Reverts Depression-Like Behaviour in Rat Female Offspring. Nutrients 2019;11:572. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11030572

Pervin M, Unno K, Ohishi T, Tanabe H, Miyoshi N, Nakamura Y. Beneficial effects of green tea catechins on neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2018;23:1297

Hidese S, Ota M, Wakabayashi C, Noda T, Ozawa H, Okubo T, Kunugi H. Effects of chronic 1-theanine administration in patients with major depressive disorder: an open-label study. Acta neuropsychiatrica 2017;29:72–79

Hidese S, Ogawa S, Ota M, Ishida I, Ysukawa, Z, Ozeki M, Kunugi H. Effects of L-Theanine Administration on Stress-Related Symptoms and Cognitive Functions in Healthy Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019;11:2362

Nobre AC, Rao A, Owen GN. L-theanine, a natural constituent in tea, and its effect on mental state. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008;17:167–168

Dong X, Yang C, Cao S, Gan Y, Sun H, Gong Y, Yang H, Yin X, Lu Z (2015) Tea consumption and the risk of depression: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 20154;9:334–345

Grosso G, Micek A, Castellano S, Pajak A, Galvano F (2016) Coffee, tea, caffeine and risk of depression: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016;60:223–234

Niu K, Hozawa A, Kuriyama S, Ebihara S, Guo H, Nakaya N, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Takahashi H, Masamune Y, Asada M, Sasaki S, Arai H, Awara S, Nagatomi R, Tsuji I. Green tea consumption is associated with depressive symptoms in the elderly. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:1615–1622

Ruusunen A, Lehto SM, Tolmunen T, Mursu J, Kaplan GA, Voutilainen S. Coffee, tea and caffeine intake and the risk of severe depression in middle-aged Finnish men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:1215–1220

Feng L, Li J, Kua EH, Lee TS, Yap KB, Rush AJ, Ng TP. Association between tea consumption and depressive symptoms in older Chinese adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2358–2360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12011

Feng L, Yan Z, Sun B, Cai CZ, Jiang HJ, Kua EH, Ng TP, Qiu CX. Tea consumption and depressive symptoms in older people in rural China. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1943–1947

Guo X, Park Y, Freedman ND, Sinha R, Hollenbeck AR, Blair A, Chen H. Sweetened beverages, coffee, and tea and depression risk among older US adults. PLoS One 2014;9:e94715. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094715

Pham NM, Nanri A, Kurotani K, Kuwahara K, Kume A, Sato M, Hayabuchi H, Mizoue T. Green tea and coffee consumption is inversely associated with depressive symptoms in a Japanese working population. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:625–633.

Li FD, He F, Ye XJ, Shen W, Wu YP, Zhai YJ, Wang XY, Lin JF. Tea consumption is inversely associated with depressive symptoms in the elderly: A cross-sectional study in eastern China. J Affect Disord 2016;199:157–162.

Kim J, Kim J. Green Tea, Coffee, and Caffeine Consumption Are Inversely Associated with Self-Report Lifetime Depression in the Korean Population. Nutrients 2018;10:1201. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091201

Chan SP, Yong PZ, Sun Y, Mahendran JCMW, Qiu C, Ng TP, Kua EH, Feng L. Associations of Long-Term Tea Consumption with Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Community-Living Elderly: Findings from the Diet and Healthy Aging Study. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2018;5:21–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2017.20

Shen K, Zhang B, Feng Q. Association between tea consumption and depressive symptom among Chinese older adults. BMC geriatrics 2019;19:246

Pham NM, Nanri A, Kurotani K, Kuwahara K, Kume A, Sato M, Hayabuchi H, Mizoue T. Green tea and coffee consumption is inversely associated with depressive symptoms in a Japanese working population. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:625–633

Feng L, Yan Z, Sun B, Cai C, Jiang H, Kua EH, Ng TP, Qiu C. Tea consumption and depressive symptoms in older people in rural China. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1943–1947

Cai H, Zheng W, Xiang YB, Xu WH, Yang G, Li H, Shu XO. Dietary patterns and their correlates among middle-aged and elderly Chinese men: A report from the Shanghai Men’s Health Study. Br J Nutr 2007;98:1006–1013

Nechuta S, Shu XO, Li HL, Yang G, Ji BT, Xiang YB, Cai H, Chow WH, Gao YT, Zheng W. Prospective cohort study of tea consumption and risk of digestive system cancers: Results from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:1056–1063

Niti M, Yap KB, Kua EH, Tan CH, Ng TP. Physical, social and productive leisure activities, cognitive decline and interaction with APOE-epsilon4 genotype in Chinese older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;11:1–15

Wei K, Nyunt MSZ, Gao Q, Wee SL, Ng TP. Frailty and Malnutrition: Related and Distinct Syndrome Prevalence and Association among Community-Dwelling Older Adults: Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:1019–1028

Nyunt MSZ, Jin AZ, Fones CSL, Ng TP. Criterion-based validity and reliability of the Geriatric Depression Screening Scale (GDS-15) in a large validation sample of community-living Asian older adults. Ageing and Mental Health 2009;13:376–382

Ng TP, Niti M, Chiam PC, Kua EH. Ethnic differences in cognitive performance on Mini-Mental State Examination in Asians. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;15:130–139

Rashidinejad A, Birch EJ, Sun-Waterhouse D, Everett DW. Addition of milk to tea infusions: Helpful or harmful? Evidence from in vitro and in vivo studies on antioxidant properties. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017;57:3188–3196

Ryan L, Petit S. Addition of whole, semiskimmed, and skimmed bovine milk reduces the total antioxidant capacity of black tea. Nutr Res 2010;30:14–20

Pan CW, Ma Q, Sun HP, Xu Y, Luo N, Wang P. Tea Consumption and Health-Related Quality of Life in Older Adults. J Nutr Health Aging. 2017;21(5):480–486.

Soh KC, Kumar R, Niti M, Kua EH, Ng TP. Subsyndromal depression in old age: clinical significance and impact. International Psychogeriatrics 2008;20:188–200

Feng L, Yap KB, Kua EH, Ng TP. Depressive symptoms, physician visits and hospitalization among community-dwelling older adults. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21:568–75

Ho CSh, Jin A, Nyunt MS, Feng L, Ng TP. Mortality rates in major and subthreshold depression: 10-year follow-up of a Singaporean population cohort of older adults. Postgrad Med 2016;128:642–647

Cherubini A, Nisticò G, Rozzini R, Liperoti R, Di Bari M, Zampi E, Ferrannini L, Aguglia E, Pani L, Bernabei R, Marchionni N, Trabucchi M. Subthreshold depression in older subjects: an unmet therapeutic need. J Nutr Health Aging. 2012 Oct;16(10):909–13.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following voluntary welfare organizations for their support: Geylang East Home for the Aged, Presbyterian Community Services, Thye Hua Kwan Moral Society (Moral Neighbourhood Links), Yuhua Neighbourhood Link, Henderson Senior Citizen’s Home, National Trade Union Congress Eldercare Co-op Ltd, Thong Kheng Senior Activity Centre (Queenstown) and Redhill Moral Seniors Activity Centre.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by research grants from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) Biomedical Research Council (BMRC Grant 03/1/21/17/214) and Ministry of Health (MOH) National Medical Research Council (NMRC 08/1/21/19/567; NMRC/CG/NUHCS/2010).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ Contributions: TPN designed research, wrote paper and had primary responsibility for final content; QG, XYG, DQLC designed and conducted research; TPN analysed data and performed statistical analyses; All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest (COI) Statement: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study: collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit manuscript for publication. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical Standards: This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the National University of Singapore Institutional Review Board (NUS-IRB; Reference Code: 04–140).

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ng, T.P., Gao, Q., Gwee, X. et al. Tea Consumption and Depression from Follow Up in the Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Study. J Nutr Health Aging 25, 295–301 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1526-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1526-x