Abstract

Objectives

To examine the association between nutritional status and frailty in older adults.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Community-dwelling older adults were recruited from 10 study sites in South Korea.

Participants

1473 volunteers aged 70–84 years without severe cognitive impairment and who participated in the Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study (KFACS) conducted in 2016.

Measurements

Nutritional status was measured using the Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF). Frailty was assessed with the Fried’s frailty index. The relationship between nutritional status and frailty was examined using the multinomial regression analysis, adjusting for covariates.

Results

Of the respondents 14.3% had poor nutrition (0.8% with malnutrition, 13.5% at risk of malnutrition). There were 10.7% who were frail, with 48.5% being prefrail, and 40.8% robust. Poor nutrition was related to a significantly increased risk of being prefrail (odds ratio [OR]: 1.59, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.09–2.32) and frail (OR: 3.30, 95% CI: 1.96–5.54).

Conclusion

Poor nutritional status is strongly associated with frailty in older adults. More research to understand the interdependency between nutritional status and frailty may lead to better management of the two geriatric conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Risk of malnutrition is quite prevalent in community-dwelling older adults, with a mean prevalence rate of 24% reported in a comprehensive review in 2006 (1). More recently, Cereda (2) reported an average prevalence of 27% and Verlaan et al. (3) reported the pooled prevalence of 19% in a meta-analysis. The average rates of overt malnutrition were 2% (1, 3) and 4% (2). Malnutrition can accelerate the age-associated decline in muscle mass and strength, increasing the risk of sarcopenia (4’6), both of which comprise the frailty syndrome. The Mini Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF) was developed as a screening instrument for malnutrition in older people (7, 8), which consists of 6 items and takes only 3 minutes to complete.

Frailty is also commonly observed in older adults living in the community, with an average prevalence rates for frailty being 17.0% (9). Frailty predisposes the older person to adverse health outcomes, such as disability, falls, and need for longterm care (10, 11). In addition, frailty increases the risk of morbidity and mortality, hospitalization, social isolation, and poor quality of life (10, 12).

Malnutrition and physical frailty in older adults are related but distinct geriatric syndromes (13). Wasting is a common phenotype of malnutrition and frailty, but the etiology may differ (14). In malnutrition, muscle wasting results from inadequate food and protein intake. Malnutrition can contribute to frailty, but frailty can be caused by chronic disease, physical inactivity, hormonal imbalances, and polypharmacy (14). Over the years the relationship between frailty and malnutrition assessed by the MNA has gained increasing attention (12, 15). It has been proposed that MNA could serve as a useful tool in assessing frailty in older adults (16, 17). However, studies examining the relationship between frailty and nutrition in Asia (18), especially in Korea that faces a rapidly aging population (19), are lacking (20).

The aim of this study was to examine the association between frailty and malnutrition in a nationwide survey of older Koreans living in the community.

Methods

Study population

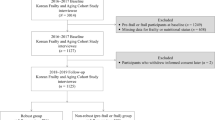

The Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort study (KFACS) was conducted in ten study sites across different regions (Seoul, Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Chungcheong, Jeolla, Gyeongsang, Jeju) in South Korea (21). The participants were recruited from community-dwelling residents in urban and rural regions nationwide, based on age- and gender-specific strata. The inclusion criteria were aged 70–84 years, living independently at home, no plans to move out in the next two years, and having no serious problems with communication. Candidates were recruited by personal contact from hospitals, public health centers, senior centers, and residence (apartment or house) in the community. Baseline evaluations were performed at ten study sites from May to November 2016 that included eight university-affiliated hospitals and two public health centers. The study was conducted following the tenets of the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kyung Hee University. All participants gave written informed consents. Among the 1559 who completed the initial assessment, those with missing values (n=86) in education, Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short Form (MNA-SF), and frailty were excluded. The sample used in the final analysis comprised of 1473.

Assessment of nutritional status

Nutritional status was assessed using the Korean version of MNA-SF (22). The MNA-SF consists of six items (A-F): anorexia (A), weight loss (B), mobility (C), stress or acute disease (D), neuropsychological problems (E), body mass index (F), which are rated from 0 to 3. A score of 12–14 indicates normal nutritional status, 8–11, at risk of malnutrition, and < 7, malnutrition. Poor nutritional status was defined as including both the at risk of malnutrition and malnutrition groups.

Assessment of frailty

Frailty was assessed according to Fried’s frailty index (11) based on five criteria: unintentional weight loss (≥ 4.5 kg in the past year), exhaustion (felt that everything was an effort or that one could not get going ≥ 3 times a week), low physical activity (23) (≤ 494.65 kcal/week for men, ≤ 283.50 kcal/week for women), low grip strength (Takei dynamometer, with < 26 kg for men and < 18 kg for women) (24), and slow gait speed (< 1.0 m/sec) (25). Frailty status was categorized into three categories according to the number of the components affected: robust (0), pre-frail (1–2), and frail (≥ 3).

Covariates

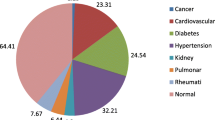

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, educational level (elementary school or lower vs. higher than elementary school), and living alone. Health status included comorbidity (2 or more self-reported, physician-diagnosed chronic diseases: circulatory system, muscular skeletal system and connective tissue, digestive system, respiratory system, nervous system, endocrine system, urogenital system, and neoplasm). Depression was defined as ≥ 8 on the 15-item Korean version of Short Form Geriatric Depression Scale (SGDS-K) (26). Cognitive function was assessed by the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination in the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) (27).

Statistical analysis

The distribution of the participants was presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), or percentages. The bivariate association between general characteristics and poor nutrition was analyzed using the independent t-test or chi-square test. The bivariate relationship between general characteristics and frailty status was analyzed using trend test or analysis of variance. We used the multinomial logistic regression analysis to examine the relationship between poor nutrition and frailty, adjusting for covariates. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. Additionally, we analyzed the association of poor nutrition with frailty by gender. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 (SPSS, International Business Machines Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

The distribution of the participants is shown in Table 1. The participants included 1473 elderly subjects (698 men and 775 women) with an average age of 76.1 (± 3.9) years. Based on the MNA-SF, 85.7% of the subjects were classified into the normal nutrition group, 13.5% were at risk of malnutrition, and 0.8% had malnutrition. Based on Fried’s frailty criteria, 40.8% were considered as robust, 48.5% as prefrail, and 10.7% as frail.

Poor nutritional status (at risk of malnutrition and malnutrition) was significantly associated with lower educational level, more depressive symptoms and lower cognitive performances (Table 2). The frailty groups differed significantly by general characteristics (Table 3). Those who were prefrail or frail were significantly more likely to be older, of female gender, have lower education, and living alone. Also, comorbidity, depression, and low cognitive ability, and poor nutrition were more prevalent among the prefrail and frail participants.

In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, poor nutritional status was associated with more than 1.5-fold and 3-fold higher risks of being prefrail and frail, respectively, adjusting for covariates (Table 4). In men, poor nutritional status exhibited a 1.8 times higher risk of prefrailty and more than a 4 times higher risk of frailty, whereas in women, a nearly 3-fold higher risk of being frail was observed.

There was also a significant association between the individual items of the MNA-SF and frailty, adjusting for age (Table 5). Anorexia and weight loss, respectively, were associated with more than 1.7-fold higher risk for being prefrail and 4.7-fold higher risk of being frail. Stress or acute disease was associated with more than 1.7-fold higher risk of being prefrail. By gender, whereas anorexia and weight loss were significantly associated with prefrail/frail in both men and women, low body mass index was significantly associated with more than 2-fold higher risk being frail in men only.

Discussion

This is the first nationwide study reporting a significant association between frailty and nutritional status using MNA-SF in community-dwelling older Korean adults. In the present study, poor nutritional status was significantly associated with both prefrailty and frailty. After adjusting for covariates, poor nutritional status as defined by at risk of malnutrition and malnutrition was positively associated with frailty. This agrees with the reviews by Guigoz (1) Cereda (2), and Verlaan et al. (3) that the risk of malnutrition in older adults increases with the level of dependency.

In addition to the overall risk of malnutrition, individual items of the MNA-SF were associated with frailty. Anorexia significantly raised the odds of prefrailty and frailty. It has been suggested that anorexia is an early risk factor of frailty (28). Weight loss was found to be associated with frailty. Unintentional weight loss, a component of Fried’s criteria, is a well-known risk factor for frailty (29). Stress or acute disease was significantly associated with prefrailty and marginally associated with frailty.

The association between nutritional status and frailty was more prominent in men than in women. This may be due to men and women having different attitudes and behaviors toward food (30, 31). Shopping for food and cooking are usually done by the wife (32), with men reporting more difficulties in preparing meals than women. The risk of malnutrition has also been considered to be greater in men living alone than women because of a decreased pleasure of eating, with a reduced food intake (33, 34). In the individual items, whereas anorexia and weight loss were significantly associated with prefrail/frail in both men and women, body mass index was significantly associated with frailty in men only. The association between low grip strength and frailty was more prominent in men (OR=20.6; 95% CI: 10.0–42.5) than in women (OR=14.3; 95% CI: 8.6–23.6), adjusted for age. Therefore, based on our results, men with BMI > 23 might have greater muscle mass, thus being less frail, while older women might have low muscle mass irrespective of BMI.

This study has some limitations. First, generalization of the study results may be limited because the sample selection was not based on random sampling. However, the distribution of the population characteristics between the national census and the KFACS population was similar (data not shown). Although the prevalence rates of frailty of the study population were comparable to other studies (9, 35, 36), the prevalence rates of overt malnutrition (0.8% versus 2–4%) and nutritional risk (13.5% versus 19–28%) appeared somewhat lower than those reported in the previous studies (1–3, 18). Second, our study design was cross-sectional and thus does not guarantee causality. Finally, the overlap of items between frailty using Fried’s phenotype model and MNA may pose as a limitation. Malnutrition and frailty has been found to be not interchangeable: in a meta-analysis, 68% of the malnourished was frail, whereas only 8.4% of the frail population was malnourished (3). We also performed a sensitivity analysis using 4 of the Fried’s criteria for frailty, excluding unintentional weight loss. Although the strength of the association between nutritional status and frailty was attenuated, the significance remained (data not shown). In future research, using different malnutrition screening tools (37) or definitions of frailty may help elucidate this relationship.

In conclusion, there was a strong correlation between nutritional status and frailty. MNA-SF may serve as a screening tool for identifying those at risk of malnutrition who in turn have an increased likelihood of prefrailty and frailty. Detection of early signs of malnutrition and improvement in the overall nutritional status might help to prevent frailty in late life. More research is warranted to better comprehend the interdependency between nutritional status and frailty, contributing to successful management of the two geriatric conditions.

Acknowledgment: This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korean Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI15C3153).

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards: The study complies with the current laws of the country in which it was performed.

References

Guigoz Y. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) review of the literature—— What does it tell us? J Nutr Health Aging 2006;10:466–485; discussion 485–487.

Cereda E. Mini nutritional assessment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2012;15:29–41.

Verlaan S, Ligthart-Melis GC, Wijers SLJ, Cederholm T, Maier AB, de van der Schueren MAE. High prevalence of physical frailty among community-dwelling malnourished older adults-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:374–382.

Bales CW, Ritchie CS. Sarcopenia, weight loss, and nutritional frailty in the elderly. Ann Rev Nutr 2002;22:309–323.

Bauer JM, Wirth R, Volkert D, Werner H, Sieber CC, Teilnehmer des BANSS-Symposiums 2006. [Malnutrition, sarcopenia and cachexia in the elderly: from pathophysiology to treatment. Conclusions of an international meeting of experts, sponsored by the BANSS Foundation]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2008;133:305–310.

Andre MB, Dumavibhat N, Ngatu NR, Eitoku M, Hirota R, Suganuma N. Mini Nutritional Assessment and functional capacity in community-dwelling elderly in Rural Luozi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2013;13:35–42.

Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging 2009;13:782–788.

Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salva A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNASF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M366–372.

Santos-Eggimann B, Cuénoud P, Spagnoli J, Junod J. Prevalence of frailty in middle-aged and older community-dwelling Europeans living in 10 countries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2009;64:675–681.

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the Concepts of Disability, Frailty, and Comorbidity: Implications for Improved Targeting and Care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:255–263.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146–156.

Espinoza S, Walston JD. Frailty in older adults: insights and interventions. Cleve Clin J Med 2005;72:1105–1112.

Laur CV, McNicholl T, Valaitis R et al. Malnutrition or frailty? Overlap and evidence gaps in the diagnosis and treatment of frailty and malnutrition. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2017;42:449–458.

Jeejeebhoy KN. Malnutrition, fatigue, frailty, vulnerability, sarcopenia and cachexia: Overlap of clinical features. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2012;15:213–219.

Dorner TE, Luger E, Tschinderle J et al. Association between nutritional status (MNA®-SF) and frailty (SHARE-FI) in acute hospitalized elderly patients. J Nutr Health Aging 2014;18:264–269.

Abellan Van Kan G, Vellas B. Is the mini nutritional assessment an appropriate tool to assess frailty in older adults? J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:159–161.

Win AZ, Ceresa C, Arnold K, Allison TA. High prevalence of malnutrition among elderly veterans in home based primary care. J Nutr Health Aging 2017;21:610–613.

Wei K, Nyunt MSZ, Gao Q, Wee SL, Ng TP. Frailty and malnutrition: related and distinct syndrome prevalence and association among community-dwelling older adults: Singapore Longitudinal Ageing Studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:1019–1028.

Korean Statistical Information Service. Future Population Estimation. http://kosis.kr/statisticsList_01.jsp?=MT_ZTITLE&parentID=A. Accessed 06 June 2017.

Jung HW, Jang IY, Lee YS et al. Prevalence of frailty and aging-related health conditions in older Koreans in rural communities: a cross-sectional analysis of the Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area. J Korean Med Sci 2016;31:345–352.

Won CW, Lee Y, Choi J, et al. Starting construction of frailty cohort for elderly and intervention study. Ann Geriatr Med Res 2016;20:114–117.

Nestlé Nutrition Institute. Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA). http://www.mnaelderly.com/mna_forms.html. Accessed 06 June 2017.

Oh JY, Yang YJ, Kim BS, Kang JH. Validity and reliability of Korean version of International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) Short Form. J Korean Acad Fam Med 2007;28:532–541.

Chen LK, Liu Lk, Woo J et al. Sarcoopenia in Asia: consensus report of the asianworking group for sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014;15:95–101.

Keimyung University Industrial-Educational Cooperation. 2008 Living Profiles of Older People Survey. Ministry of Health and Welfare & Family, Seoul, 2009.

Cho MJ, Bae JN, Seo KH, Ham BJ, Kim CK, Lee DW, Kang MH. Validation of Geriatric Depression Scale, Korean Version (GDS) in the Assessment of DSM-III-R Major Depression. Journal of the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 1999;38:48–63.

Lee DY, Lee KU, Lee JH et al. A normative study of the CERAD neuropsychological assessment battery in the Korean elderly. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004;10:72–81.

Morley J. Anorexia of aging: A true geriatric syndrome. J Nutr Health Aging 2012;16:422–425.

Chin A Paw MJ, de Groot LC, van Gend SV, Schoterman MH, Schouten EG, Schroll M, van Staveren WA. Inactivity and weight loss: effective criteria to identify frailty. J Nutr Health Aging 2003;7:55–60.

Beardsworth A, Bryman A, Keil T, Goode J, Haslam C, Lancashire E. Women, men and food: the significance of sex for nutritional attitudes and choices. Br Food J 2002;104:470–491.

Wardle J, Haase AM, Steptoe A, Nillapun M, Jonwutiwes K, Bellisle F. Sex differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med 2004;27:107–116.

Sidenvall B, Nydahl M, Fjellström C. The meal as a gift—the meaning of cooking among retired women. J Appl Gerontol 2000;19:405–423.

Charlton KE. Elderly men living alone: are they at high nutritional risk? J Nutr Health Aging 1999;3:42–47.

Pearson JM, Schlettwein-Gsell D, van Staveren W, de Groot L. Living alone does not adversely affect nutrient intake and nutritional status of 70- to 75-year-old men and women in small towns across Europe. Int J Food Sci Nutr 1998;49:131–139.

Hoeck S, François G, Geerts J, Van der Heyden J, Vandewoude M, Van Hal G. Health-care and home-care utilization among frail elderly persons in Belgium. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:671–677.

Garcia-Garcia FJ, Gutierrez Avila G, Alfaro-Acha A et al. The prevalence of frailty syndrome in an older population from Spain. The Toledo Study for Healthy Aging. J Nutr Health Aging 2011;15:852–856.

Htun NC, Ishikawa-Takata K, Kuroda A et al. Screening for malnutrition in community dwelling older Japanese: preliminary development and evaluation of the Japanese Nutritional Risk Screening Tool (NRST). J Nutr Health Aging 2016;20:114–120.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Lee, Y., Won, C.W. et al. Nutritional Status and Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Korean Adults: The Korean Frailty and Aging Cohort Study. J Nutr Health Aging 22, 774–778 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1005-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-018-1005-9