Abstract

How do Black, Latinx, and White people who believe they are mistaken as a member of another racial group perceive the amount of racial discrimination they experience, and what role does skin tone play? Using the Texas Diversity Survey (TDS), I analyze the amount of discrimination Black people, Latinxs, and Whites report when they believe others do not see them as their self-identified race. The data show that skin tone is connected to racial identity mismatch for all aforementioned groups. In addition, Latinxs with lighter- or darker-skin who believe others see them as Latinx report more racial discrimination than medium-skinned Latinxs who believe strangers do not see them as Latinx; Whites with darker-skin who believe others see them as White report less discrimination; and age is one of the most significant predictors of discrimination for Black and White respondents. I suggest that the Black-White binary continues to divide Black and White people across identity measures and emphasizes how racial identity is quite complex for Latinxs. The inter-related nature of these concepts means that if we better understand one aspect, we have a more accurate conceptualization of race in the twenty-first century and are closer to exposing the various factors connected to racial discrimination, particularly as the percentage of racial minorities in the USA increases. This timely work has implications for racial discrimination among relatively stable groups (Black and White people) and the largest and fastest growing minority group in the USA (Latinxs).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the USA, when people believe strangers see them as White, do they report less everyday racial discrimination than when they believe they are seen as Black or LatinxFootnote 1? This concept, racial identity mismatch, refers to the discrepancy between an individual’s racial self-identification and how they believe others see them (Gonlin et al. 2019). For example, someone may consider themselves Black or Latinx (or both) and yet think that other people see them as White, which could allow for increased access to White spaces but can simultaneously cause community and/or internal tension. Racial identity mismatch is associated with variations in health (Campbell and Troyer 2007, 2011; Stepanikova 2010), community cohesion (Gonlin et al. 2019), and racial identity (Vargas and Stainback 2016). The present study connects racial identity mismatch, racial discrimination, and colorism by comparing the amount of racial discrimination reported by people who believe that they are seen as their self-identified race to those who believe that they are seen as another racial group and factoring in the impact of having lighter, medium, and darker skin tones. This study seeks to (1) use Bonilla-Silva’s theory of the “Latin Americanization” of race to consider how Latinxs are incorporated into the contemporary US racial system; (2) determine whether discrimination among Black and White people shifts based on racial identity mismatch; and (3) focuses on variations in discrimination experienced by Black people, Latinxs, and Whites by skin tone.

Everyday discrimination is particularly important to analyze in states like Texas, where the population is already comprised of more than 50 percent people of color (Teixeira et al. 2015). As the USA as a whole is becoming more majority-minority (Colby and Ortman 2015), we can look to states like Texas to see how residents are perceiving their racialized experiences. The Texas Diversity Survey (TDS; Keith and Campbell 2015) is an excellent source for this study because it includes information on perceived discrimination, skin tone, self-identified race, and reflected race in a state that is already majority-minority.

This study is particularly useful to researchers considering the ramifications of our socially constructed notions of racial identification, reflected race, and skin tone; and scholars, demographers, and policymakers concerned with the mechanisms contributing to variations in racial discrimination among relatively stable groups (Black and Whites) and the largest and fastest growing minority group in the USA (Latinxs).

Background

Someone’s self-identified race can differ from their reflected race (Brunsma 2006). Racial identification (also referred to as racial self-classification) is the racial group (e.g., Black, White, Asian, American Indian) which an individual fills out on a form, such as the US Census (Roth 2016; Saperstein and Penner 2012), while reflected race refers to the racial group individuals believe other people assign to them (Roth 2016). Not to be mistaken with racial misclassification,Footnote 2 in which an individual’s race is incorrectly categorized by others (e.g., Frost et al. 1992; Stepanikova 2010; Vargas and Stainback 2016), I use racial identity mismatch to emphasize instances when an individual believes their race is identified in a manner that differs from their self-reported race. Sosina and Saperstein (2018) find that the reflected race is a better predictor of material hardship than self-identified race, indicating the significance of reflected race.

Skin Tone and Racial Identity Mismatch

In the Black Community

Black people in the USA have a history of being classified by others as Black if they have “one drop” of Black blood, also known as hypodescent (Davis 1991; Jordan 2014). During American slavery, regardless of how a person self-identified or how light their skin was, the one-drop rule was used to classify any person with a Black ancestor as Black and treat them as such. Therefore, part-Black people have historically been incorporated into the Black community. This historical tendency impacts how Black people today are viewed and treated by both in- and out-group members (Hollinger 2003; Khanna 2010), which increases the likelihood of holding a Black identity and believing others see them as Black. Indeed, most Black people tend to be classified as Black by others (Campbell and Troyer 2011).

However, as contemporary US notions of multiculturalism have increased, there are more racial identification options available to mixed-race people (Masuoka 2010; Morning 2018). Lighter-skinned Black people and people with part-Black ancestry may be incorporated into Black, mixed race, and other spaces (Khanna 2012). Their skin tone and perceptions of how others see them have ramifications (Khanna 2010; Khanna and Johnson 2010) that are markedly different in the twenty-first century than at previous times in history. Therefore, I expect that self-identified Black people will tend to believe that others see them as Black, and that this racial identity match will be strongest for darker-skinned and weakest for lighter-skinned Black people.

In the Latinx Community

The concept of “race” is particularly complex for Latinxs. Hispanics are categorized as an ethnic group by the US Census, yet in recent years an overwhelming selection of a “Hispanic” ethnicity and “Other” race on these Census questions indicate that the majority of Hispanics/Latinxs in the US do not see their race properly captured by this question formatting. Scholars of race and ethnicity debate whether Hispanicity/Latinidad should continue to be asked separately from the race question (thereby treating Hispanics/Latinxs as a panethnic group), or combined with the race questions by adding Hispanic/Latinx as a racial group (thereby interpreting Hispanics/Latinxs as a racial group). Researchers find that, for the majority of Hispanics/Latinxs in the US, these experiences are better captured using (at least) the combined question format (Allen et al. 2011), particularly as Hispanics/Latinxs are racialized and frequently treated as a group different from White, Black, Asian, and other groups (Telles 2012).

Latinxs are one of the groups most likely to experience racial identity mismatch (Alba et al. 2016; Campbell and Troyer 2011; Saperstein 2006). Latinxs who believe they are usually misclassified most often believe they are perceived as White (Campbell and Troyer 2011). Scholars also find differences by gender, with Latinas perceived as White, while Latinx men are mistaken as Mediterranean (Flores-González 2017). Varying histories of Latinx groups in the US also means that groups employ Whiteness in different ways. Dating back to the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, which specifies that Mexicans living on land that would become part of the USA are to be classified and treated as White, claiming Whiteness was used by many Mexican Americans to assert a right to citizenship. According to Telles and Ortiz (2008), this tradition of Latinxs identifying as White continues in Texas, regardless of skin tone or experiences of discrimination. Dowling (2014) similarly finds that many Latinxs in Texas identify as White because Whiteness is viewed as synonymous with Americanness and the (hopeful) end of discrimination. Furthermore, Devos and Banaji (2005) find that the national category of “American” is more equated with Whiteness than with Blackness or Asianness. Given the politicized nature of racial identification and the extant literature on Whiteness, the respondents in this Texas-based data set may be disproportionately more likely to identify as White on a form. However, I expect that the shifting racial demographics in Texas, the southwest, and throughout the USA will lead contemporary respondents to recognize racial discrimination in new ways.

Broadening from a Texas context, researchers consistently find that lighter-skinned Latinxs are more likely to racially identify as White (Frank et al. 2010; Golash-Boza and Darity Jr. 2008). In addition, Vargas (2015) finds that lighter skin and higher socioeconomic status are associated with Latinxs believing that others see them as White. Thus, for Latinxs, believing others see them as White centers on skin tone and SES. Furthermore, Golash-Boza and Darity (2008) find that skin tone on its own and skin tone interacted with discrimination impact Latinx identity. Specifically, darker-skinned Hispanics are more likely to identify as Black or Other than as White, and very dark-skinned Hispanics are highly likely to identify as Black, compared to White. People with darker skin and increased discrimination are more likely to identify as Black, Other, or Hispanic and less likely to identify as White (Golash-Boza and Darity Jr. 2008). Golash-Boza (2006) notes that Latinxs who experience discrimination are less likely to identify as “American.” Hence, skin tone, discrimination, and the two factors together, influence identity for Latinxs in the USA.

In the White Community

Out of all racial groups, Whites are the most likely to be racially classified correctly—people who identify as White are generally identified as White by others (Campbell and Troyer 2011). The clarity and general consensus around who is considered White stems from the historical boundaries set to keep Whiteness “pure” and separate from other racial groups. Historically, (relatively) darker-skinned Eastern and Southern European immigrants were considered “conditionally white” and, regardless of asserting themselves as White, were treated by the descendants of Western European immigrants (i.e., European colonizers) as less intelligent than Whites but more intelligent than Black people (Roediger 2005). Regardless of their self-identification, how others saw them (racial classification) and how they believed others saw them (reflected race) influenced their interactions. These darker-skinned “White ethnics” were eventually subsumed into the White category. Yet even as phenotypic associations with Whiteness have shifted, lighter skin continues to be the defining characteristic of Whiteness.

If darker skin is associated with identification as Black or Latinx and lighter skin is associated with Whiteness, I hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1

As skin tone darkens, racial identity match increases for Black people and Latinxs and decreases for Whites.

Latin Americanization Thesis and Social Construction

I expect Latinxs to experience discrimination in line with the theory of Latin Americanization of race introduced by Bonilla-Silva (2004) and expanded by him and his colleagues (Bonilla-Silva 2017; Bonilla-Silva and Dietrich 2011; Bonilla-Silva and Glover 2004). Bonilla-Silva postulates that Latinxs and specific other racial and ethnic groups will fall between Black people and Whites regarding their experiences with race in the USA. Bonilla-Silva speculates that US society will move from a “biracial” White versus non-White racial order to a “triracial” White, honorary White, and collective Black racial order. He further expects that Latinxs will be divided into this triracial system by skin color and phenotype, with White Latinxs (also referred to as White-passing) joining the White category, lighter-skinned Latinxs forming an honorary White category, and darker-skinned Latinxs joining the collective Black category. In this way, Bonilla-Silva’s predictions on the incorporation of Latinxs into the US racial hierarchy lead me to expect Latinxs will experience more racial discrimination than Whites and less than Black people, controlling for skin tone.

In addition to the Latin Americanization thesis, I use a social constructionist perspective. Race is not a fixed characteristic of an individual, but rather socially created in specific social spaces and contexts, and therefore, the experience of it will vary depending on place and individual and group characteristics (Campbell 2007; Cornell and Hartmann 2007; Nagel 1994; Omi and Winant 2014; Roth 2010). For example, US understandings of race tend to be more rigid (e.g., the Black-White binary) than Latin American understandings of race, and the boundaries of race have shifted gradually but only for some racial groups (e.g., Eastern and Southern Europeans who historically were seen as off-White are now considered White (Roediger 2005)). While socially constructed, the concept of race has important consequences, especially for people who have been devalued throughout US history due to their race (Cornell and Hartmann 2007; Hirschman 2004; Morning 2009; Omi and Winant 2014; Waters 1990).

Colorism

Colorism—privileges associated with lighter skin as compared to darker skin—has historical roots. Given the parallel and connected histories of European colonialism of African and Latin American indigenous people, colorism influences Black and Latinx communities in a remarkably similar way.Footnote 3 A skin color hierarchy stems from and enables a social, political, and economic structure that benefits the colonizer, as higher status and privilege is associated with lightness (i.e., Europeans) and lower status is associated with darkness (i.e., Africans and indigenous peoples) (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2014; Darity Jr. et al. 2005; Hall 1998; Stephens and Fernández 2012).

Scholars debate the continued significance of skin tone on racial identity and other phenomena (Dowling 2015; Gullickson 2005; Herman 2004; Telles and Ortiz 2008), but overwhelmingly find that skin tone is significantly associated with racial discrimination (Darity Jr. et al. 2005; Hall 1998; Hebl et al. 2012; Hunter 2002; Stephens and Fernández 2012). Specifically, researchers find that Black Americans with darker skin report higher amounts of discrimination (Klonoff and Landrine 2000; Monk 2015; Uzogara et al. 2014; Uzogara and Jackson 2016), and the same may be said for Latinxs in the USA (Araujo Dawson 2015; Ortiz and Telles 2012; Santana 2018). I question how all skin tone, racial discrimination, and racial identity mismatch are connected.

In the Black Community

Establishing skin color hierarchy during chattel slavery enabled slave owners to minimize slave rebellions by introducing meaning to differences between enslaved Africans (Hunter 2002). Perceived as closer to whiteness (regardless of the consensual or non-consensual manner by which they obtained this skin color), lighter-skinned slaves were treated better than darker-skinned slaves, generating animosity and distrust among slaves, which minimized the likelihood of a large slave population banding together to revolt (Hunter 2002). In the twenty-first century, Black people with darker skin continue to be perceived more negatively inter- and intra-racially and are more likely to experience multiple forms of discrimination than lighter-skinned Black people (Glenn 2009; Hagiwara et al. 2012; Hebl et al. 2012; Monk 2014, 2015). Skin tone discrimination leads many darker-skinned Black people to have significantly worse health outcomes, including depression and self-rated mental and physical health (Monk 2015). Additionally, darker-skinned Black people in the USA generally have lower levels of educational attainment, household income, marital attainment, and political attainment than lighter-skinned counterparts (Goldsmith et al. 2006, 2007; Hamilton et al. 2009; Herring et al. 2004; Keith and Monroe 2016; Weaver 2012). Klonoff and Landrine (2000) go as far as to assert that skin tone is a marker of discrimination, an assertion supported by their findings that darker-skinned Black people are eleven times more likely than lighter-skinned Black people to report high levels of racial discrimination.

However, the effect of skin tone is not always linear. Medium-skinned Black people may avoid discrimination more than both lighter- and darker-skinned Black people. For example, Louie (2019) finds that mental disorder was more common among Black adolescents with very dark skin compared to Black adolescents with medium brown skin, but no skin tone difference was found between Black people with lighter skin. Relatedly, Celious and Oyserman (2001) theorize that Black people experience both in-group colorism (prejudice from other Black people that privileges having medium skin) and out-group colorism (discrimination from Whites that privileges having lighter skin), a theory tested and supported by Monk (2015), Uzogara et al. (2014) and Uzogara and Jackson (2016). For example, lighter-skinned Black people are more likely to have their Black authenticity questioned than medium- or darker-skinned Black people (Hunter 2002) and hence experience rejection by co-ethnics. Therefore, I test the effects of light skin and dark skin as two dummy variables compared to medium skin.

In the Latinx Community

The children of European and Latin American indigenous peoples (consensual and non-consensual) relations who were lighter skinned were considered by European colonizers to be closer to whiteness and therefore better than darker indigenous peoples. These histories help explain why, contemporarily, HispanicsFootnote 4 with the lightest skin are more likely than Hispanics with the darkest skin are reported by interviewers to be having high intelligence, a significant relationship independent of respondents’ education and vocabulary test scores (Hannon 2014). Furthermore, darker-skinned Latinxs are more likely to be racially profiled and to experience state violence (Goldsmith et al. 2009), have lower life chances and psychological well-being (Montalvo and Codina 2001), and earn less than lighter-skinned counterparts doing the same work (Gómez 2000). Latinas who are immigrants and darker skinned report lower self-esteem, lower feelings of attractiveness, and a desire to lighten their skin color, compared to US -born peers, leading Telzer and Vazquez Garcia (2009) to assert that skin color is a central factor for immigrant Latinas’ well-being.

As with Black people, skin color is not unidirectional for Latinxs. Stephens and Fernández (2012) note that their findings go against most other research: in their sample of self-identified White Hispanic women, “tan” skin is preferred over “pale” skin and associated with increased desirability among peers, value in dating situations, sexual appeal to men, and a marker of Hispanic identity in social settings. This study emphasizes the connection between skin tone and reflected identity, with tan skin considered closer to perceptions of what it means to be Latina. Hence, while lighter skin may be generally connected to decreased discrimination and darker skin associated with increased discrimination, medium skin may be associated with Hispanicity or Latinidad. Therefore, I test the effects of lighter skin and darker skin compared to medium skin among Latinxs.

Skin Tone Variation among Whites

Historically, pale skin was a proxy for social class among Europeans, indicating status as an aristocrat who did not have to labor outside (Lacey 1983). Blue blood, a term used for European nobles and royalty, refers to those whose veins appear blue under their very pale skin. Blue blood, a concept recorded as early as 1834, was used to denote purity and distinguish Europeans from darker-skinned colonized peoples (Calvo-Quirós 2013; Carrera 2003; Lacey 1983). This mentality was carried over by Western Europeans who colonized the Americas. When darker-skinned Europeans immigrated to the USA in the nineteenth century they were treated as conditionally White, a category in between whiteness and person of color status (Roediger 2005).

Contemporarily, tanned skin has replaced pale skin as a representation of Whites’ social class. Tanned skin is now indicative of the luxury to tan on vacation. Yet there are limitations to the meaning of tanned skin among Whites: having tanned to redness indicates a working class background, in which individuals toil outdoors (Flora and MacKethan 2002; Slade et al. 2012). In addition, darker-skinned Whites could be perceived as more racially ambiguous. Hence, the meaning of skin tone has shifted for Whites in a way that it has not for racial minorities, and darkened skin means different things for Whites. I, therefore, do not expect darker skin to be associated with increased racial discrimination for Whites. I expect to find no significant differences in racial discrimination reported by Whites due to skin tone.

Racial Discrimination and Racial Identity Mismatch

In this study, I measure perceived, everyday racial discrimination which involves unfair treatment that people believe they encounter. This is not necessarily the “actual” amount of discrimination they are subjected to and does not evaluate the intentional versus unintentional nature of these experiences. Perceived discrimination emphasizes the awareness and internal processing of events, which has important mental health impacts and is related to how people believe others see them (Sellers and Shelton 2003) and strength of racial/ethnic identity (Gong et al. 2017). Everyday discrimination is typically routine and individual incidents are seemingly “minor,” with a focus on chronic interpersonal interactions (Essed 1991; Williams et al. 1997). Using their everyday discrimination scale (EDS), Williams et al. (1997) find that increased frequency of everyday discrimination is associated with significant decreases in well-being and significant increases in self-reported ill health, psychological distress, and number of days physically incapacitated due to physical health and emotional distress. If a person believes they are discriminated against, their physical and emotional health declines.

Centuries of systematic denigration of Black people via slavery, black codes, Jim Crow, segregation, and convict labor are contemporarily reproduced in new forms, such as the school-to-prison pipeline, high rates of incarceration of Black people, and redlining, to name a few (Alexander 2012; Coates 2017; Hattery and Smith 2018). Given this, I anticipate that Black respondents in this study will report high levels of racial discrimination, particularly people who believe they are seen as Black.

Historical and contemporary racialization in the USA is also apparent for Latinxs, and in particular Mexicans and Mexican Americans. The current political climate of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and detention centers is the outcome, in part, of the USA’s history of creating the Border Patrol in the 1920s, Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s, the Bracero Program 1942–1964, and the southern border wall initially constructed in the 1990s (Chavez 2013; Massey et al. 2002; Mize and Swords 2011; Ngai 2004). Therefore, I anticipate Latinxs (the majority of whom in the TDS are Mexican or Mexican American) to report high levels of racial discrimination, particularly if they believe others perceive them as Latinx.

Everyday discrimination reported by racial minorities reflects the current US racial hierarchy, with African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans reporting the highest amounts of racial discrimination and Asians and Latinxs reporting the least among groups of color (Gong et al. 2017). Herman (2004) finds that darker-skinned multiracials perceived higher amounts of discrimination and linked this perceived discrimination with a racial minority identity. These studies indicate that Blackness and darker skin are connected to increased racial discrimination and may influence racial identity. I expand the reach of these studies to explore these phenomena among Black, Latinx, and White people, noting that darker skin is connected to intra- and inter-racial discrimination for groups of color. If darker skin is associated with identification as Black or Latinx, and lighter skin with closer proximity to Whiteness, I hypothesize that those who believe they are perceived as Black or Latinx will report more racial discrimination:

Hypothesis 2

Latinxs who believe strangers see them as Latinx will report higher amounts of discrimination compared to Latinxs who believe strangers see them as White.

Hypothesis 3

Black people who believe strangers see them as Black will report higher amounts of discrimination compared to Black people who believe strangers see them as non-Black people of color.Footnote 5

Data and Methods

The Texas Diversity Survey (TDS) provides data on racial identity, skin tone, reflected racial identity, and perceived discrimination reported by Black, Latinx, and White Texas residents. I use TDS to analyze how perceptions of imposed racial identifications collide with self-identifications by using data that directly asked respondents about reflected race and discrimination due to race.

TDS is a telephone survey of adults living in Texas conducted by the Public Policy Research Institute at Texas A&M University (Keith and Campbell 2015).Footnote 6 Ninety-eight percent of the completed surveys are conducted on cellular phones.Footnote 7 Respondents answer questions in either English or Spanish, depending on their preference. Black people are systematically sampled in TDS to ensure a sufficient number of responses from this subgroup; to address this stratified sampling strategy, responses are weighed in Stata using the svy commands with weights constructed from the 2014 American Community Survey by age, race, and sex population estimates. I include respondents (N = 1306) who were successfully matched to their Zip Code Tabulation Area (ZCTA) of residence. Geographically matched data from the 2010 to 2014 American Community Survey allow for construction of additional explanatory variables, such as the percent of Latinxs and percent of Black people in each ZCTA. I include only the respondents with valid information on all of the key variables included in Table 1 below and use listwise deletion to drop any respondents with missing data, bringing the total sample size to N = 1093.

Key Variables

Self-identified Race

Respondents are asked “What is your racial or ethnic background? Please choose ALL that apply.” Their options include Black or African American, White, European American, or Anglo, Hispanic or Latino/a, Asian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Native American, and Other. I did not reclassify respondents who selected multiple racial categories into a monoracial category, as I expect their experiences with racial identity and reflected race differ from that of self-identified monoracials. Instead, I drop these respondents from the analyses.

Latinxs are often measured (especially in federal surveys) as an ethnic group which was then asked to also racially identify as Black, White, or other races in a separate question. The TDS uniquely asks Latinidad using a combined question format that included Latinxs as a racial group category. I analyze the Latinxs in TDS who chose Latinx-only, rather than incorporating Latinxs who chose multiple racial categories. This decision ensures that I analyze racial identity mismatch among self-identified Latinx-only, so that when these respondents indicate that they were seen as White or Black, this is unambiguously inconsistent with their racial identification.

Reflected Race

Respondents are asked “What race or ethnicity do strangers usually think you are?” and are provided the same set of race response options given for self-identified race, but are asked to choose just one. I drop Latinxs who believe they are seen as Black (N = 1), Whites who believe they are seen as Black (N = 1), and Black people who believe they are seen as White (N = 3), because these very small numbers that prevent me from providing robust analyses. Descriptive statistics shown in Table 1 indicate that Latinxs report the highest amount of racial identity mismatch, with only 74% of Latinxs believing that strangers saw them as their self-identified race, compared to 87% of Black people and 93% of Whites.

Everyday Racial Discrimination

Self-reported discrimination is collected with two different question formats. Both formats ask whether the respondent experiences poor treatment in everyday situations, such as when shopping in a store or eating in a restaurant, with half of the sample prompted to report experiences of racial or ethnic discrimination and the other half of the sample asked to report any kind of discrimination and subsequently identify the cause of the mistreatment. The first group is prompted, “In your day-to-day life have any of the following things happened to you because of your race or ethnicity? Would you say almost every day, at least once a week, a few times a month, a few times a year, or less than a year” and then immediately asked about 10 examples, as shown in Table 2.

The second group is asked about the same 10 types of mistreatment without any mention of why they were mistreated and was provided a follow-up question about the primary cause of the mistreatment, with race and ethnicity as two of the options (others included age, gender, sexual orientation, and religion).

I combine those who reported mistreatment based on race/ethnicity from either format with a dummy variable controlling for which format they received.Footnote 8 Those who report a different type of discrimination are coded as not experiencing racial discrimination. Respondents indicate experiencing racial discrimination on a sliding scale of 0 to 5. A response of 0 indicates “I never experience that,” 1 indicates “less than once a year,” 2 indicates “a few times a year,” 3 indicates “a few times a month,” 4 indicates “at least once a week,” and 5 indicates “I experience that almost every day.” I check for outliers among all groups, and drop one Latinx respondent reporting a discrimination level of 5 (after dropping this one person, the next highest level among Latinxs is 4.1) and one White respondent reporting a discrimination level of 4.8 (after dropping this person, the next highest response among Whites is 3.2) to avoid skewing the data. I estimate OLS models, all of which are run as two-tailed tests, to determine the relationships between the aforementioned variables. As a sensitivity measure, I also test these models with only respondents who are prompted to report racial discrimination.

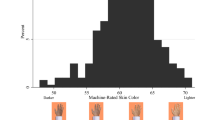

Skin Tone

To determine self-rated skin tone, participants are asked the following question: “How would you describe your skin color/complexion? Compared to most people in my racial or ethnic group, I believe my skin color is…” and are given the option of choosing very light (1), light, medium, dark, or very dark (5).

Controls

In addition to the above variables, I include gender, working full time, household income, percent Latinx in the ZCTA, percent Black in the ZCTA, age, education, and immigrant status. Gender is coded as a dummy variable where females = 1, and working is coded as respondents who are employed full time = 1. To measure household income, respondents are asked “What is your total household income before taxes? Include your income and any other members of your household.” They are then provided nine categories: $10,000 and under; $10,001–$20,000; $20,001–$30,000; $30,001–$45,000; $45,001–$60,000; $60,001–$75,000; $75,001–$100,000; $100,001–$250,000; and more than $250,000.

Racialization is contextual and may vary by space (Omi and Winant 2014); the geographic space that people reside in could impact how they believed others racially classified them (Gonlin et al. 2019). In addition, racial demographics of an area can impact residents’ attitudes and perceptions of discrimination, as documented by group threat theorists and research on racial demographic shift (Craig and Richeson 2017; Danbold and Huo 2015; Hempel et al. 2012). I account for variations in the racial composition in a geographic area by including racial percentage breakdowns in ZCTAs. Percent Latinx in a ZCTA and percent Black in a ZCTA are constructed from the Latinx and Black populations, respectively, and the total population in a ZCTA was based on the ACS. The zip codes where respondents lived were geocoded using the ZCTAs provided by the Census Bureau. The ZCTAs are created by assigning Census blocks to the residential zip code that occurs most frequently within that block. I include the percent of residents who identify as Latinx or Black in a ZCTA to test whether any relationship between racial identity mismatch and discrimination is driven by the significantly greater representation of Latinx or Black residents in the ZCTA.

To measure age, respondents are asked “How old are you?” without being prompted to put their age into an age range or category. I group these responses into 5-year age categories (e.g., 45–49 years) because some respondents did not provide an exact year. While age could have been measured as a continuous variable, analyzing it as such may hide important differences between age groups (e.g., middle-aged people may have different discrimination reporting patterns than younger or older generations, a difference that would be hidden using a continuous variable). Therefore, I analyze age by categories. Education is measured as the highest level of schooling completed.

Immigrant status is associated with racial discrimination, as recent immigrants tend to be discriminated differently than descendants of immigrants. Later generations descended tend to be more fluent in English and progress economically to a certain extent, compared to first-generation immigrants (Telles and Ortiz 2008). A lighter-skinned person of color who is a recent immigrant could face racialized discrimination related to their immigrant status rather than their skin tone. Therefore, I control for immigrant status: first- or second-generation immigrant was calculated from the questions “Were you born in the USA?” “Was your mother born in the USA?” and “Was your father born in the USA?” Anyone who was not born in the USA or had one or more parents who were not born in the USA was categorized in a combined variable, as first- or second- generation immigrant. For Black and White respondents, I combine first- and second-generation immigrants to avoid further dividing already small racial identity mismatch cell sizes in order to include an aspect of immigrant status. For Latinxs, the sample sizes of first-generation immigrants (N = 86) and respondents with immigrant parents (N = 165) are large enough to disaggregate, so for this population I include two different control variables. Dividing this group into first-generation only and second-generation only immigrants would have excluded respondents who are immigrants and have immigrant parents (N = 83). Therefore, I include the variables first-generation immigrant (1 = respondent is born outside the U.S., 0 = respondent is born in the U.S.) and respondent with immigrant parent(s) (1 = one or both parents are born outside the U.S., 0 = both parents are U.S. born) in the models for Latinxs.

Results

The goal of the present study is to determine how the specific relationships between skin tone and racial identity mismatch, racial identity mismatch and discrimination, and the control variables differ for various racial groups. In comparing Black people, Latinxs, and Whites, I find skin tone significantly impacts racial identity mismatch for all groups. Racial identity mismatch and skin tone alone are not significantly connected to racial discrimination for any of these groups, but interaction of skin tone with racial identity match yields significant results for Latinxs and Whites. As suggested by the extant literature, certain control variables are significantly connected to these relationships to varying degrees depending on the group in question.

Skin Tone and Racial Identity Mismatch

To determine the relationship between skin tone and racial identity mismatch, I estimate OLS models shown in Table 3. I find that, compared to medium-skinned counterparts, lighter-skinned Black people (− 0.16, p < 0.05) and lighter-skinned Latinxs (− 0.19, p < 0.01) are less likely to believe others see them as Black or Latinx, respectively, while lighter-skinned Whites are more likely to believe others see them as White (0.04, p < 0.05). Darker-skinned Black people are more likely to believe others see them as Black (0.13, p < 0.01), darker skin tone is not significant for Latinxs, and darker-skinned Whites are less likely to report match (− 0.27, p < 0.01). Being a first-generation immigrant is significantly associated with a match in Latinx identity (0.21, p < 0.01) as well. Latinxs living in a predominantly Latinx area are more likely to believe others see them as Latinx (0.24, p < 0.05), and Whites living in a predominantly Black area are more likely to believe others see them as White (0.15, p < 0.05).

I test the interaction of skin tone and income and skin tone and education, given that researchers find skin tone interacted with SES (which is generally measured as a combination of income, education, and occupation) impacts the race people believe others classify them as. In this model, education, which was previously not significantly connected to racial identity match, is significant for all three groups. Black and White medium-skinned respondents with a high school diploma or greater are less likely to believe others see them as Black (− 0.15, p < 0.05) or White (− 0.08, p < 0.05), respectively. Medium-skinned Latinxs with a high school diploma or more are marginally more likely to believe others see them as Latinx (0.14, p < 0.10). However, the interaction between skin tone and education is not significant, nor is income or the interaction between skin tone and income, on racial identity match, as shown in Table 4 below.

Racial Identity Mismatch and Discrimination

I estimate OLS regression models to assess the relationship between racial identity mismatch, skin tone, and discrimination, shown in Table 5. Neither racial identity match nor skin tone is significantly associated with racial discrimination. Rather, age, working full time, and income are significantly associated with racial discrimination. Black and White people who are 50 years or older are significantly less likely to perceive racial discrimination than younger counterparts (Blacks: − 0.38, p < 0.01; Whites: − 0.20, p < 0.05). In addition, Black people who work full time are significantly more likely (0.34, p < 0.05) to perceive racial discrimination, and as income increases Whites are less likely (− 0.05, p < 0.05) to perceive racialized discrimination. The only statistically significant variable associated with Latinxs’ reported discrimination is percent Black in a ZCTA—as the percentage of Black people in a ZCTA increases, Latinxs’ reported racial discrimination increases. Being prompted to report racial discrimination did not significantly impact Black people’s responses, but marginally decreased Latinxs’ reported discrimination (− 0.29, p < 0.10) and significantly decreased Whites’ reported discrimination (− 0.29, p < 0.05). As a sensitivity test, I run these models again without skin tone and find the same results (available upon request).

I test the interaction between skin tone and gender, given the immense body of research indicating that colorism operates differently among men and women. In these analyses, presented in Table 6, skin tone interacted with gender is not statistically significantly associated with reported discrimination. I also interact skin tone with racial identity match and find that Latinxs with lighter skin and racial identity match are more likely (0.73, p < 0.01) to report discrimination, as are Latinxs with darker skin and racial identity match (0.91; p < 0.05), compared to Latinxs with medium skin who believe strangers do not see them as Latinx. Meanwhile, Whites with darker skin and racial identity match are marginally less likely (−0.74; p < 0.10) to report discrimination, compared to Whites with medium skin who believe strangers do not see them as White. In addition, I analyze the impact of skin tone interacted with education on discrimination and find it is not significantly associated with racial discrimination for any of the three groups. Finally, I test the interaction between skin tone and income on discrimination (available upon request) and find that lighter-skinned Black people who earn 100,001 to 250,000 (−1.77, p < 0.01) report significantly less racial discrimination than medium-skinned Black people earning $45,000 to 60,000; lighter-skinned Latinxs who earn $30,001 to $45,000 (0.81, p < 0.10) report significantly more racial discrimination compared to medium-skinned Latinx earning 45,001 to 60,000; and darker-skinned Whites who earn 60,001 to 75,000 report less discrimination than medium-skinned Whites earning 45,001 to 60,000. In Table 6 below, I include analyses of all the aforementioned interaction effects in a combined model, with the exception of income due to the large number of income categories.

Discussion

Skin Tone and Racial Identity Mismatch

Among Black people, Latinxs, and Whites, the closer they are to popular perceptions of what it means to be a member of a specific racial group, the more likely they are to feel seen as a group member. If Black people are conceptualized as darker, Latinxs as medium, and Whites as lighter skinned, it is unsurprising that lighter-skinned Black and Latinx people and darker-skinned Whites feel strangers do not see them as a member of the group they claim.

Unlike Latinxs, racial identity mismatch is an uncommon phenomenon among self-identified Black and White people in TDS. This finding is in line with the majority of research that focuses on differences in racial identity and observed race: Saperstein (2006) finds the two measures to be consistent for Black people and Whites but not for “Others,” and Alba et al. (2016) determine that self-reported and observed race overlap for the majority of Black and White people, but less so for Hispanics. The racial makeup of geographic location is important: Latinxs living in a predominantly Latinx area being more likely to believe others see them as Latinx and Whites living in a predominantly Black area being more likely to believe others see them as White fits with the idea that the racial demographics of a community significantly influence someone’s own racialized perceptions.

For Latinxs in this sample, skin tone and immigrant status are the most significant predictors for racial identity match, with lighter-skinned Latinxs reporting significantly less match than medium-skinned Latinxs and first-generation Latinx immigrants reporting significantly more racial identity match than all other generations. That being a first-generation immigrant is significantly associated with racial identity match for Latinxs is in line with the USA's current social construction of Latinxs as immigrants. This gives credence to the significance of immigrant status, and that immigrants vary by immigrant generation (Telles and Ortiz 2008). The findings that skin tone interacted with income and skin tone interacted with education are not significantly related to racial identity match goes against Vargas’ (2015) finding that lighter skin and higher SES are associated with Latinxs believing others see them as White. This may be indicative of our different measures—in this study, education and income are treated as variables in their own right. Perhaps a combined measure, such as SES, leads to outcomes not presented by these variables on their own. In addition, this Texas-based sample may have different characteristics than the nationally representative samples used by other researchers. The results reported herein support the notion that racial identification on a form, which notably may be used to reflect political identity (Dowling 2015; Telles 2018), is more complex for Latinxs across identity measurements. Furthermore, these findings suggest that the Black-White binary continues to effectively divide Black and White people across identity measures.

Racial Identity Mismatch and Discrimination

Respondents experiencing racial identity mismatch should theoretically perceive differences in racial discrimination, yet the Black respondents in this study report no significant differences. Black people who believe they are not seen as Black are not reporting a difference in discrimination, which goes against research indicating that lighter-skinned Black people and Black/White biracials (who generally are lighter-skinned) report feeling rejected as not Black enough (Khanna 2011), and that Black people with more stereotypically Black features experience greater discrimination from out-group members (Hebl et al. 2012). Khanna’s finding focuses on intra-racial discrimination within the Black community, and Hebl et al. (2012) emphasize interracial discrimination, whereas the discrimination variables in the TDS do not specify the source of discrimination. Therefore, respondents may report discrimination from multiple sources (e.g., lighter-skinned Black people might report greater discrimination from in-group members and darker-skinned Black people might report greater discrimination from out-group members), which may cancel each other out so that no statistically significant differences are found.

In addition, the only skin-tone related difference I find is lighter-skinned Black people earning 100,000 to 250,000 are less likely to report discrimination than medium-skinned counterparts earning 45,001 to 60,000. It is perhaps unsurprising that lighter-skinned Black people with this high income level report significantly less discrimination: they may interpret their economic success as the breaking down of racial barriers, and may have experienced less out-group discrimination due to their lighter skin privilege. Hochschild and Weaver's (2007) skin tone paradox helps explain the otherwise lack of significance: even though darker-skinned Black people are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status, have a higher likelihood of punishment from the criminal justice system, and are less likely to hold political office than their lighter-skinned counterparts (Johnson and King 2017; King and Johnson 2016; Weaver 2012), Hochschild and Weaver (2007) find that perceptions of discrimination do not vary by skin tone. They explain that middle class Black people (who are more likely to be lighter-skinned) are more likely to be in predominantly White environments, leading them to recognize their experiences as racial discrimination. While working class Black people experience racial discrimination, they are less likely to assert it as such, perhaps because they perceive most people around them to also be experiencing this, leading them to de-emphasize the amount of racial discrimination they personally experience or be less inclined to interpret their experiences as discriminatory (Hochschild and Weaver 2007). Therefore, reported racial discrimination focusing on skin tone may present statistically insignificant results because there are likely important differences in the groups respondents are comparing themselves with.

I find age significantly predicts reported racial discrimination among Black people. Watts Smith (2014) finds that period and cohort effects largely explain discrepancies in discrimination reported by different generations of Black people. First, regardless of age, Black people have become less likely to assert discrimination as a credible explanation because they have lived through macro-level cultural changes, such as the first Black president; and second, younger cohorts of Black people are more likely to use individualist rather than structural reasons to explain why Black people socioeconomically fall behind Whites (Watts Smith 2014). Older Black respondents in my study may be less likely to report discrimination due to memories of events like Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement (i.e., cohort effect), which they may interpret as “actual” discrimination that has since lessened. Younger adults without these memories may instead focus on the everyday discrimination they experience and the systemic racism that has brought movements such as Black Lives Matter, and have a definition of discrimination that may embody both overt and covert racism.

While skin tone is an important predictor of racial identity mismatch, I do not find skin tone or racial identity mismatch alone to be significantly associated with perceived racial discrimination for Black respondents. Additional factors, such as phenotype, body type, style, and mannerisms, may be used to assert Blackness, negating the effect of skin tone in this context. For example, Schachter et al. (2019) indicate that observers may rely on ancestry, skin color, social class, name, language, religion in determining someone else’s race. While the present study focuses on reflected rather than observed race, their discussion of the factors influencing observed race suggests some of these characteristics may influence reflected race, which I argue may influence perceived discrimination.

The results presented herein indicate three important predictors for racial discrimination reported by Latinxs. First, as the percentage of Black people in a ZCTA increases, Latinxs’ reported racial discrimination increases. This may be explained by group threat—two different groups vying for resources may have greater animosity as the size of one group increases (Barreto and Sanchez 2014; Gay 2006; McClain et al. 2006; Oliver and Wong 2003). Second, lighter-skinned Latinxs who believe others see them as Latinx and darker-skinned Latinxs who believe others see them as Latinx reporting more discrimination than medium-skinned Latinxs who believe others see them as non-Latinx emphasizes the importance of racial identity match. Believing others see them as Latinx significantly impacts perceived discrimination at both ends of the skin tone spectrum. Latinxs in this Texas-based study may view the racial discrimination they face as exacerbated if others see them as Latinx because of the emphasis on controlling the “browning of America” (Craig and Richeson 2017; Hempel et al. 2012), the phenotype-based nature of stop-and-frisks (Torres 2015), and the conflation of immigrants with criminality (Stumpf 2006). Hence, believing strangers see them as Latinx is understandably connected to increased reports of racial discrimination. Finally, income interacted with skin tone is connected to significant differences in reported discrimination. That lighter-skinned Latinxs earning 30,001 to 45,000 report significantly more discrimination than medium-skinned Latinxs one income bracket higher (45,001 to 60,000) provides evidence that increased class status may be associated with believing racial discrimination is not a factor in hiring decisions.

Using the triracial system theory, I expected to find skin tone alone to be significant for Latinxs in their reporting of discrimination, but the data do not support these expectations. Bonilla-Silva posits that darker-skinned Latinxs will be subsumed into the Collective Black category, experiencing more racialized discrimination. However, the darker-skinned Latinxs in this sample do not report more discrimination than their medium-skinned counterparts. This may potentially be due to colorblindness and association of a White identity with Americanness, as Dowling (2014) found with her Texan Latinx respondents; survey questions inquiring about a colorblind framework would be useful in future studies to determine. In addition, Bonilla-Silva expects that lighter-skinned Latinxs will be incorporated into the Honorary White category and experience less discrimination, yet lighter-skinned Latinxs in TDS do not report significantly more or less discrimination than medium-skinned Latinxs. Rather, I find skin tone interacted with racial identity match is key, and that these results are in line with research focusing on the significance of the intersections of race and income. Perhaps greater variation in Latinxs’ skin tone, the incorporation of self-identified Afro-Latinxs, and including racial identity match, or at least a reflected race measure, may be used in future studies.

Finally, that the small percentage of Whites who believe they are seen as people of color do not report more racial discrimination indicates that this perceived loss of White status is not associated with the consequence of discrimination. They may subscribe to colorblind racial ideology, the most common ideology among Whites (Bonilla-Silva 2017; Lopez Bunyasi 2019), in which they may de-emphasize race and therefore racial discrimination. The interaction of darker-skin and racial identity match for Whites is marginally associated with less discrimination, which may indicate darker skin in this case is used as a proxy for class status (i.e., having the luxury to tan), which fits with the finding that increased income is associated with less reported racial discrimination among Whites. I find age and income to be the only control variables that significantly predict reported discrimination among Whites. Younger Whites may be more likely to perceive racial discrimination because they are more likely to be held accountable for racist remarks (e.g., the advent of social media increases the likelihood of being fired due to insensitive comments) and may interpret increased opportunities for people of color as a loss of opportunities for Whites (e.g., claims of reverse racism). These events are less likely to occur for older Whites (for example, older Whites are likely not applying to colleges). Indeed, Lopez Bunyasi (2019) finds that Whites who believe their group does worse on the job market than Black Americans and feel that being White is detrimental to their job prospects were especially likely to vote for Trump in 2016 in an effort to “reclaim” racial advantages. Similarly, identifying as White, believing Whites are discriminated against, and feeling tied to White people are connected with voting for a White candidate (Schildkraut 2017), and changing racial demographics are associated with Whites' increased fear of replacement (Pérez Huber 2016). Whites with lower income reporting significantly more racial discrimination may indicate they are more likely to perceive discrimination due to their Whiteness than Whites with greater income. This is indicative of the significance of the interaction effect of race and class, in that Whites with less income may be more likely to face disparaging comments, such as “redneck,” that are used to negatively describe working class Whites. Higher income Whites may be less likely to experience such slurs, therefore reporting less racial discrimination because discrimination is both racialized and class-based.

Limitations

White Latinxs–Latinxs who are White-passing and/or identify as White—and Afro-Latinxs—people who identify as Black and Latinx—may have unique experiences not captured in this data. While TDS includes respondents who identify as multiracial and may choose Latinx as one of their component groups, it is unclear whether respondents are identifying as multiracial or are identifying as a specific type of Latinx. Relatedly, respondents are only allowed to choose one category for reflected race, and I am interested in whether or not respondents believe others see them as how they see themselves. Therefore, I analyze people who explicitly self-identified as only Black, Latinx, or White. In addition, TDS does not provide information on the race(s) of the perpetrator(s) who discriminated against respondents, which is an important consideration as Khanna (2011) found that the race of the perpetrator can impact (in her case, Black/White biracial) respondents’ racial identity formation. It logically stems that the race of the perpetrator could influence whether respondents believe they are seen as their self-identified race. This paper is a step in the direction of recognizing the relationship between discrimination, skin tone, and racial identity mismatch; future data collectors may consider including questions on the source of the discrimination.

In addition, people of different national origins have varying sociohistoric relations with identity politics in the USA, which leads to differences in self-perception and experiences of racialization (Nelson and Tienda 1997; Telles 2018). Given that the majority of Latinxs in Texas claim Mexican ancestry (87% in 2014: Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends 2014), Latinxs in this study are grouped together under a panethnic “Hispanic or Latino/a” identity, but likely are dominated by Mexicans and Mexican Americans, which may mask important within-group differences. I am not able to disaggregate based on national origin, as TDS does not provide this information; I encourage future analyses using detailed data on national origin. Relatedly, the TDS does not include a measure of respondents’ English fluency, which is an important predictor in discrimination and racialization. While the majority of respondents opted to take the survey in English (93 percent of all respondents) rather than Spanish (seven percent), the present study does not capture how level of comfort with English relates to mismatch and discrimination.

Finally, the distribution of skin tone among Latinxs ranges from 1 to 3 with an average of 1.74 and of Whites ranges from 1 to 3 with an average of 1.54, indicating that most of the Latinxs and Whites in this sample consider themselves to be on the lighter end of the spectrum compared to others in their group. Respondents self-rated their skin tone in relation to others in their group. Monk (2015) finds self-rated skin tone to be a better measure of perceived discrimination among Black Americans than interviewer-rated skin tone, but this finding may or may not apply to Latinxs or Whites. For example, Latinxs may be inclined to view themselves as lighter because it is connected to higher status (Schwartzman 2007). Uzogara (2019) finds that at higher levels of SES, lightest-skinned Latinas report lower discrimination and darker-skinned Latinas report more discrimination. Self-rated skin tone is theoretically related to perceived discrimination across groups as perceptions of skin tone may be related to one’s perceptions of racial discrimination.

Conclusion

Racial identity mismatch and its consequences (in this study, racial discrimination) are experienced differently by various racial groups. Future analyses of racial identity mismatch should incorporate, when possible, the experiences of multiple groups to gain a fuller understanding of and appreciation for racial identity mismatch. For example, in the future, researchers may consider comparing Afro-Latinxs who believe they are seen as Latinx to those who believe they are seen as Black to measure potential differences between groups and better understand the experiences of Afro-Latinxs. Racial identity mismatch is likely quite common among groups that are frequently miscategorized, such as Filipinos (Ocampo 2016) and Afro-Latinxs, and more racially ambiguous groups, such as bi- and multiracials, a group continuing to grow numerically (Jones and Bullock 2012; Pew Research Center 2015).

In terms of racial discrimination, these results emphasize the importance of age-related perceptions of what may be considered racial discrimination by various generations of Black and White respondents, and the interaction of skin tone and racial identity match for Latinxs in particular. The implications of these findings are vital for understanding racial identification, racial identity mismatch, skin tone, and discrimination. The inter-related nature of these concepts means that if we better understand one aspect we have a more accurate conceptualization of race in the twenty-first century and are closer to exposing the various factors connected to everyday discrimination, particularly as the percentage of racial minorities in the USA increases. This timely work prepares scholars, legislators, and professionals to anticipate future demographic trends, be more able to address psychological needs considering multiple dimensions of race, and connect micro- and macro-tiers of our shifting society.

Change history

15 May 2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-020-09292-2

Notes

Throughout this paper, I describe Hispanics and Latina/o/xs as a racial group and use the term “Latinx” because this word is gender neutral and refers to largely the same population as “Hispanic” while allowing the focus to be on people of Latin American ancestry. I refer to Black people in the U.S. as “Black” rather than “Black American” or “African American” in order to be inclusive of Black immigrants, who are a small but important portion of the Black population in the U.S. In addition, I use the phrase “Black people” to emphasize the humanity of a group that has historically been denied this recognition.

Since racial misclassification is the way others categorize a person that does not correspond with how that person would categorize themselves, it may unintentionally lead to the assertion that there is one “true” racial categorization, when in fact racial identity is fluid and may change over time and social context.

Though largely similar, there are important differences in the histories of colonialism of African and Latin American peoples and the use of colorism. Namely, the promotion of mestizaje to encourage race mixing in Latin America which is used to deny colorism (Chavez-Dueñas et al. 2014), and the more fluid understanding of race in many Latin American countries compared to the U.S. (Telles 2018).

I use “Hispanic” here to remain consistent with the language used by Hannon (2014), given that “Latinx” and “Hispanic” refer to groups that are not perfectly overlapping.

The number of self-identified Black respondents who believe others see them as White (N = 3) is too small for reliable analyses.

To access the Texas Diversity Survey, researchers can email Mary Campbell (m-campbell@tamu.edu) requesting a copy of the data set.

14.1 percent of respondents completed the survey. Cell phone surveys have relatively low response rates (recent averages are about 9 percent), but are more effective at reaching hard-to-survey populations, such as people of color, young people, and working people (Keeter et al. 2017; Link et al. 2007). The Pew Research Center finds cell phone survey responses are generally similar to traditional surveys, except that they have more civically-engaged respondents with higher average levels of education (Keeter et al. 2017).

I include this dummy variable in all analyses of discrimination, and find that the coefficients are never significant at p < .05, indicating that the level of discrimination reported across the two formats is similar.

References

Alba, R., Insolera, N. E., & Lindeman, S. (2016). Comment: Is race really so fluid? Revisiting Saperstein and penner’s empirical claims. American Journal of Sociology, 122(1), 247–262.

Alexander, M. (2012). The new jim crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New York: The New Press.

Allen, V. C., Lachance, C., Rios-Ellis, B., & Kaphingst, K. A. (2011). Issues in the assessment of ‘race’ among Latinos: Implications for research and policy. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 33(4), 411–424.

Araujo Dawson, B. (2015). Understanding the complexities of skin color, perceptions of race, and discrimination among cubans, dominicans, and puerto ricans. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 37(2), 243–256.

Barreto, M. A., & Sanchez, G. R. (2014). A ‘southern exception’ in Black-Latino attitudes? Perceptionos of competition with African Americans and other Latinos. In T. Affigne, E. Hu-DeHart, & M. Orr (Eds.), Latino politics en ciencia política: The search for latino identity and racial consciousness. New York: The New York University Press.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2004). From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(6), 931–950.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2017). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in America (5th ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bonilla-Silva, E., & Dietrich, D. (2011). The enchantment of color-blind racism in Obamerica. The Annals of American Academy of Political and Social Science, 634(1), 190–206.

Bonilla-Silva, E., & Glover, K. S. (2004). ‘We Are All Americans’: The Latin Americanization of Race Relations in the United States. The changing terrain of race and ethnicity (pp. 149–183). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Brunsma, D. (2006). Public categories, private identities: Exploring regional differences in the biracial experience. Social Science Research, 35(3), 555–576.

Calvo-Quirós, W. A. (2013). The politics of color (Re) significations: Chromophobia, chromo-eugenics, and the epistemologies of taste. Chicana/Latina Studies, 13(1), 76–116.

Campbell, M. E. (2007). Thinking outside the (Black) box: Measuring black and multiracial identification on surveys. Social Science Research, 36, 921–944.

Campbell, M. E., & Troyer, L. (2011). Further data on misclassification: A reply to Cheng and Powell. American Sociological Review, 76(2), 356–364.

Carrera, M. M. (2003). Imagining identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the colonial body in portraiture and casta paintings. Texas: University of Texas Press.

Celious, A., & Oyserman, D. (2001). Race from the inside: An emerging heterogeneous race model. Journal of Social Issues, 57(1), 149–165.

Chavez-Dueñas, N. Y., Adames, H. Y., & Organista, K. C. (2014). Skin-Color prejudice and within-group racial discrimination. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 36(1), 3–26.

Chavez, L. R. (2013). Latino threat: Constructing immigrants, citzens, and the nation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Coates, T.-N. (2017). We were eight years in power: An american tragedy. New York: BCP Literary Inc.

Colby, S. L., & Ortman, J. M. (2015). Projections of the size and composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060. Washington DC: Census Bureau.

Cornell, S., & Hartmann, D. (2007). Ethnicity and race: Making identities in a changing world (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2017). Hispanic population growth engenders conservative shift among non-hispanic racial minorities. Social Psychological and Personality Science., 4, 383–392.

Danbold, F., & Huo, Y. J. (2015). No longer ‘“All-American”’? Whites’ defensive reactions to their numerical decline. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(2), 210–218.

Darity, W. A., Dietrich, J., & Hamilton, D. (2005). Bleach in the rainbow: Latin ethnicity and preference for whiteness. Transforming Anthropology, 13(2), 103–109.

Davis, F. J. (1991). Who Is black? One nation’s definition. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Devos, T., & Banaji, M. R. (2005). American = White? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 447–466.

Dowling, J. A. (2014). Mexican Americans and the question of race. Texas: The University of Texas Press.

Dowling, J. A. (2015). Mexican Americans and the questions of race. Texas: University of Texas Press.

Essed, P. (1991). Understanding everyday racism: An interdisciplinary theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Flora, J., & MacKethan, L. (Eds.). (2002). The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, genres, places, people, movements, and motifs (pp. 729–730). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Flores-González, N. (2017). Citizens but Not Americans: Race and belonging among Latino Millenials. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Frank, R., Akresh, I. R., & Bo, Lu. (2010). Latino immigrants and the U.S. racial order. American Sociological Review, 75(3), 378–401.

Frost, F., Taylor, V., & Fries, E. (1992). Racial misclassification of Native Americans in a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results cancer registry. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 84(12), 957–962.

Gay, C. (2006). Seeing difference: The effect of economic disparity on black attitudes toward Latinos. American Journal of Political Science, 50(4), 982–997.

Glenn, E. N. (Ed.). (2009). Shades of difference: Why skin color matters. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Golash-Boza, T. (2006). Dropping the hyphen? Becoming Latino(a)-American through racialized assimilation. Social Forces, 85(1), 27–55.

Golash-Boza, T., & Darity, W. (2008). Latino racial choices: The effects of skin colour and discrimination on latinos’ and latinas’ racial self-identifications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 31, 899–934.

Goldsmith, A. H., Hamilton, D., & Darity, W. (2006). Shades of discrimination: Skin tone and wages. The American Economic Review, 96(2), 242–245.

Goldsmith, A. H., Hamilton, D., & Darity, W. (2007). From dark to light: Skin color and wages among African-Americans. Journal of Human Resources, 42(4), 701–738.

Goldsmith, P. R., Romero, M., Goldsmith-Rubio, R., Escobedo, M., & Khoury, L. (2009). Ethno-racial profiling and state violence in a southwest barrio. Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies, 34(1), 93–124.

Gómez, C. (2000). The continual significance of skin color: An exploratory study of latinos in the northeast. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 22(1), 94–103.

Gong, F., Jun, Xu, & Takeuchi, D. T. (2017). Racial and ethnic differences in perceptions of everyday discrimination. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 3(4), 506–521.

Gonlin, V., Jones, N. E., & Campbell, M. E. (2019). On the (racial) border: Expressed race, reflected race, and the U.S.-Mexico border context. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 6, 1–18.

Gullickson, A. (2005). The significance of color declines: A re-analysis of skin tone differentials in post-civil rights America. Social Forces, 84(1), 157–180.

Hagiwara, N., Kashy, D. A., & Cesario, J. (2012). The independent effects of skin tone and facial features on Whites’ affective reactions to Blacks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(4), 892–898.

Hall, R. E. (1998). Skin color bias: A new perspective on an old social problem. The Journal of Psychology, 132(2), 238–240.

Hamilton, D., Goldsmith, A. H., & Darity, W. (2009). Shedding ‘light’ on marriage: The influence of skin shade on marriage for black females. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 72(1), 30–50.

Hannon, L. (2014). Hispanic respondent intelligence level and skin tone. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 36(3), 265–283.

Hattery, A. J., & Smith, E. (2018). Policing black bodies: How black lives are surveilled and how to work for change. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Hebl, M. R., Williams, M. J., Sundermann, J. M., Kell, H. J., & Davies, P. G. (2012). Selectively friending: Racial Stereotypicality and social rejection. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1329–1335.

Hempel, L. M., Dowling, J. A., Boardman, J. D., & Ellison, C. G. (2012). Racial threat and white opposition to bilingual education in Texas. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 35(1), 85–102.

Herman, M. R. (2004). Forced to choose: Some determinants of racial identification in multiracial adolescents. Child Development, 75(3), 730–748.

Herring, C., Keith, V., & Horton, H. D. (Eds.). (2004). Skin deep: How race and complexion matter in the “color-blind” era. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Hirschman, C. (2004). The origins and demise of the concept of race. Population and Development Review, 30(3), 385–415.

Hochschild, J. L., & Weaver, V. M. (2007). The skin color paradox and the american racial order. Social Forces, 86(2), 643–670.

Hollinger, D. A. (2003). Amalgamation and hypodescent: The question of ethnoracial mixture in the history of the United States. The American Historical Review, 108(5), 1363–1390.

Hunter, M. L. (2002). ‘If you’re light you’re alright’: Light skin color as social capital for women of color. Gender and Society, 16(2), 175–193.

Jones, N. A., & Bullock, J. (2012). The two or more races population: 2010. Retrieved https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-13.pdf.

Johnson, B. D., & King, R. D. (2017). Facial profiling: Race, physical appearance, and punishment. Criminology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 55(3), 520–547.

Jordan, W. D. (2014). Historical origins of the one-drop racial rule in the United States. Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies, 1(1), 99–132.

Keeter, S., Hatley, N., Kennedy, C., & Lau, A. (2017). What low response rates mean for telephone surveys. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Keith, V. M., & Campbell, M. E. (2015). Texas Diversity Survey [computer file]. Texas: College Station.

Keith, V. M., & Monroe, C. R. (2016). Histories of colorism and implications for education. Theory Into Practice, 55(1), 4–10.

Khanna, N. (2010). "If you’re half black, you’re just black’” reflected appraisals at the persistence of the one-drop rule. Sociological Quarterly, 51(1), 380–397.

Khanna, N. (2011). Biracial in America: forming and performing racial identity. Minneapolis: Lexington Books.

Khanna, N. (2012). Multiracial Americans: Racial identity choices and implications for the collection of race data. Sociology Compass, 6(4), 316–331.

Khanna, N., & Johnson, C. (2010). Passing as black: Racial identity work among biracial Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly, 73(4), 380–397.

King, R. D., & Johnson, B. D. (2016). A punishing look: Skin tone and afrocentric features in the halls of justice. American Journal of Sociology, 122(1), 90–124.

Klonoff, E. A., & Landrine, H. (2000). Is skin color a marker for racial discrimination? Explaining the skin color-hypertension relationship. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 23(4), 329–338.

Lacey, R. (1983). Aristocrats. Tornoto: McClelland and Stewart.

Link, M. W., Battaglia, M. P., Frankel, M. R., Osborn, L., & Mokdad, A. H. (2007). Reaching the U.S. cell phone generation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 71(5), 814–839.

Lopez Bunyasi, T. (2019). The role of whiteness in the 2016 presidential primaries. Perspective on Politics, 17(3), 679–698.

Louie, P. (2019). Revisiting the cost of skin color: Discrimination, mastery, and mental health among black adolescents. Society and Mental Health, 10(1), 1–19.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Malone, N. J. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Masuoka, N. (2010). The ‘multiracial’ option: social group identity and changing patterns of racial categorization. American Politics Research, 39(1), 176–204.

McClain, P. D., Carter, N. M., Soto DeFrancesco, V. M., Lyle, M. L., Grynaviski, J. D., Nunnally, S. C., et al. (2006). Racial distancing in a Southern City: Latino immigrants’ views of Black Americans. Journal of Politics, 68(3), 571–584.

Mize, R. L., & Swords, A. C. S. (2011). Consuming Mexican labor: From the bracero program to NAFTA. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Monk, E. P. (2014). Skin Tone stratification among Black Americans, 2001–2003. Social Forces, 92(4), 1313–1337.

Monk, E. P. (2015). The cost of color: Skin color, discrimination, and health among African-Americans. American Journal of Sociology, 121(2), 396–444.

Montalvo, F. F., & Edward Codina, G. (2001). Skin color and Latinos in the United States. Ethnicities, 1(3), 321–341.

Morning, A. (2009). Toward a sociology of racial conceptualization for the 21st century. Social Forces, 87, 1167–1192.

Morning, A. (2018). Kaleidoscope: Contested identities and new forms of race membership. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(6), 1055–1073.

Nagel, J. (1994). Constructing ethnicity: Creating and recreating ethnic identity and culture. Social Problems, 41(1), 152–176.

Nelson, C., & Tienda, M. (1997). The structuring of hispanic ethnicity: Historical and contemporary perspectives. In M. Romero, P. Hondagneu-Sotelo, & V. Ortiz (Eds.), Challenging fronteras: Structuring latina and latino lives in the US (pp. 7–29). New York: Routledge.

Ngai, M. M. (2004). Impossible subjects: Illegal aliens and the making of modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ocampo, A. C. (2016). The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans break the rules of race. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Oliver, J. E., & Wong, J. (2003). Intergroup prejudice in multiethnic settings. American Journal of Political Science, 47(4), 567–582.

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2014). Racial formation in the United States (3rd ed.). London: Routledge.

Ortiz, V., & Telles, E. (2012). Racial identity and racial treatment of Mexican Americans. Race and Social Problems, 4(1), 41–50.

Pérez Huber, L. (2016). Make America great again: Donald Trump, racist natvism, and the virulent adherence to white supremacy amid U.S. demographic change. Charleston Law Review, 10(2), 215–249.

Pew Research Center Hispanic Trends. (n.d.) Demographic Profile of Hispanics in Texas, 2014.

Pew Research Center. (2015). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse and growing in numbers. Multiracial in America. Retrieved //www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-inamerica/st_2015-06-11_multiracial-americans_00-06/.