Abstract

While the black population of the USA has grown more diverse with regard to ethnicity and class status, most research on racial identity relies on dichotomous proxies of racial group identification created during the civil rights era. Using a subset of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity included in the National Longitudinal Survey of Freshmen, a representative sample of black students at twenty-eight selective American colleges and universities, we test how black student racial identity is related to students’ ethnic, nativity, socioeconomic, and contextual experiences in childhood. Our more nuanced measure of black racial identity shows that being Black/African American is central to the new generation of black elites’ self-identity and that, contrary to prior evidence and theorization that blacks are either assimilationist or nationalist, that black students express strong support for both assimilationist and nationalist ideological beliefs at the same time. In addition, students express strong tendencies toward group membership as well as individualism; race has less of an impact on how they feel about themselves and their social relationships. Further analyses reveal substantial variation in black identity between monoracial and mixed-race blacks, and between immigrant (both first and second generation) and native blacks, but few social class differences. Notably, childhood experiences of racial segregation and social disorganization are also strongly associated with black identity and racial ideologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction and Theoretical Framework

BlackFootnote 1 racial identity is critical to understanding the potential for social mobility and racial mobilization efforts (Cohen 1999). However, most sociological research on black racial identity uses outdated proxies for racial identity and pays scant attention to how nativity, social class, and/or mixed-race origins may differentially impact racial group consciousness, group identification, as well as individual self-concept, and fails to focus on the sociocultural identities of the “Post-Integration Generation” (Simpson 1998). Despite the rising prominence of the black middle class, increased immigration from the Caribbean and Africa, and the politicization of the mixed-race movement, there has been minimal exploration of what blackness means for different segments of the black population. In social science research—particularly in sociology—black identity has long been considered a “product of assignment” (Eggerling-Boeck 2002), and blacks as a group considered a homogeneous racial and ethnic group defined by “a common descent (Africa as a homeland), a distinctive history (slavery in particular), and a broad sense of cultural symbols (from language to expressive culture) that are held to capture much of the essence of peoplehood” (Cornell and Hartmann 1998, p. 33).

We argue that traditional conceptions of black identity greatly hamper research on racial identity and ideology in sociology. Hence, we take a first cut at analyzing how members of the new black elite understand their racial identities in light of other salient identities, including racial classification, nativity status, social class characteristics, and racial segregation and its consequences using a more nuanced measure of racial identity, the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI). Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Freshmen (NLSF), a representative sample of more than 700 black students at twenty-eight selective American colleges and universities, we examine the presence, strength, and importance of multiple dimensions of black identity and provide a better and more accurate sense of the salience of race to blacks’ sense of self, and the degree to which racial self-concept is associated with a particular ideological perspective or worldview. We pay particular attention to whether and how diverse demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual characteristics influence claims of a black identity and the articulation of how that identity matters in their lives.

Our research questions are threefold: (1) How do these relatively privileged black college students conceptualize the centrality of blackness and its political implications in their lives? (2) In what ways might family immigration history, social class, and racial segregation influence racial centrality and ideology? And (3) In what ways do the racial identities of elite black college students challenge traditional dichotomous understandings of black racial ideology and what it means to be Black/African American in the post-Civil Rights, so-called postracial era?

Academic Studies of Black Identity

Most sociological research measures black identity by considering just two components of group identity: racial group identification and racial group consciousness. Sociologists describe racial group identification as “feelings of closeness to similar others in ideas, feelings, and thoughts” (Broman et al. 1988, p. 148, see also Allen et al. 1989; Demo and Hughes 1990; Parham and Williams 1993; Thornton et al. 1997; Smith and Moore 2000) that presupposes a psychological attachment to the racial group (Chong and Rogers 2005). Historically, racial group consciousness has permeated black identity research as a way to understand “[black Americans] separate-subordinate status in American life” (Drake and Clayton 1962, p. 390) and is considered integral to membership in the black community; group members must collectively unite to elevate their status within the social hierarchy. Undergirding this concept are “the tendency toward ideological identification,” solidarity, and common fate (Brown 1931, p. 90; Ferguson 1938; Gordon 1964; Blauner 1972; Gurin et al. 1989; Dawson 1994).

Early efforts to measure racial group identification used disparate antiwhite attitudes and militancy scales, pro-black attitudes, and political participation and were largely uninterested in intraracial differences in sociodemographic characteristics (Marx 1967; Tomlinson 1970; Kronus 1971; Rosenberg and Simmons 1971; Banks 1976; Porter and Washington 1979). Blacks espousing assimilationist perspectives were considered lacking in racial consciousness and not “down with the cause.” Later research incorporated a black nationalist perspective to examine how sociodemographic characteristics such as social class, age, gender, region, and urbanicity affect group identification and attachment (e.g., Allen and Hatchett 1986; Broman et al. 1988; Allen et al. 1989; Demo and Hughes 1990; Parham and Williams 1993). Here, too, researchers studied blacks’ racial consciousness, as defined by feelings of closeness to other blacks as well as their resultant behaviors and interests (Gurin et al. 1980). Drawn from general-purpose surveys and geographically restricted samples of mostly adult poor and working class African Americans, no consensus exists over which measures actually gauge racial identification or group consciousness, and political ideology was considered synonymous with black identity (Schuman et al. 1985; Herring 1989; Hughes and Demo 1989; Sigelman and Welch 1994).

Such conflations of racial identity with specific ideologies and/or group consciousness were always imprecise proxies for racial identity. That imprecision may be even more flawed for(1) a black American population that was born into de facto instead of de jure segregation, (2) a multiracial black population that was never forced to check only one census box, (3) the more than 10 % of blacks who are first- or second-generation black immigrants (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2011), and (4) a black population with increasing socioeconomic status diversity (Charles et al. 2008; Landry and Marsh 2011; Hunt and Ray 2012).

Black America Redefined: Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Social Context Diversity

The increasing diversity of the American black population challenges notions of a singular racial identity, bringing issues of racial legitimacy and politics to the fore. Seventeen percent of blacks in the USA are young professionals earning at least $75,000 (DeNavas-Walt et al. 2013). More than one-tenth of blacks in the USA are first- and second-generation immigrants from Africa or the Caribbean Africa (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2011) and come to the USA with comparatively high levels of human capital; similarly, self-identified mixed-race blacks are eight percent of the total US black population (U.S. Bureau of the Census 2011; Thomas 2011). Mixed-race blacks and black immigrants from the Afro-Caribbean have long been a viable presence among the black American elite (Bryce-Laporte 1972; Gatewood 2000). Though each is a relatively small subset of the total black population, all are overrepresented among black students enrolled in elite American colleges and universities (Massey et al. 2003; Charles et al. 2008).

At a 2004 Harvard University Black Alumni function, professors Henry Louis Gates and Lani Guinier asserted that up to two-thirds of the university’s black students were not multigenerational Americans but rather first- and second-generation immigrants of Caribbean or African origin, and/or of mixed-race heritage (Rimer and Arenson 2004). Just a few years later, President Barack Obama’s self-classification as African American—despite his advantaged immigrant and mixed-race origins—spurred political conflict and partisan debate about the contemporary salience of race (Bobo 2001; Bobo and Charles 2009). President Obama is said to embody the realization of The Dream—elected on the basis of his qualifications, not the color of his skin (Obama 2006; Navarrette 2008). Even as an example of the significant intraracial diversity in the American black population, and his policies and self-identity are often the source of heated intraracial political debate, he nonetheless garners near universal political support within the black community (for a rare exception, see West and Buschendorf 2014).

Political scientist Michael Dawson’s (1994) concepts of the black utility heuristic and black linked fate help explain that political support. Dawson argues that black group consciousness strengthens political participation especially among higher-status blacks (those that are largely college-educated), and encourages group members to work together to improve their collective status. Dawson contends that the “key to understanding the self-categorization process for African Americans is the fact that the social category ‘Black’ in American society cuts across multiple boundaries” (1994, p. 76). Dawson roots black linked fate in the shared historical experiences of black Americans and defines the black utility heuristic as a decision-making strategy among privileged black Americans where they equate their racial group interests as proxies for individual interests (see also Dawson 2001). He does not, however, disaggregate black subgroups and critics argue that his model cannot keep pace with increasing economic, ethnic, and gender diversity (Simpson 1998; Cohen 1999; Lacy 2007; Tate 2010; Davis 2011), or account for the increasing “saliency of blacks’ social identities beyond race” (McKenzie and Harris 2010, p. 5).

In light of the increasing demographic diversity of black Americans, newer sociological and political research questions whether black immigrants, multiracial and affluent black Americans mobilize and unite around issues such as neighborhood/school segregation, education, immigration, employment, gender, and/or political candidates (Gay 2004; Simien 2005; Rogers 2006; Smooth 2006; Price 2009; Spencer 2011; Greer 2013; Sharkey 2014; Smith 2014). Results from these studies suggest that black Americans do, in fact, have different racial ideologies and that the meaning of blackness varies across the racial group and often changes over time and across contexts (Gay 2004; Herman 2004; Masuoka and Junn 2008; Saperstein and Penner 2010; Spencer 2011; Torres and Massey 2012; Greer 2013; Smith 2014; Kramer et al. 2015).

Research on first- and second-generation African and Afro-Caribbean immigrants suggests that these groups consider themselves culturally distinct from multigenerational native-born blacks, and may, therefore, have differing notions of racial group membership (Vickerman 1999; Waters 1999; Mossakowski 2003; Rogers 2006; Greer 2013). Over time, however, and as a consequence of first-hand experiences with present-day racial discrimination, black immigrants develop both an attachment to the racial group and a sense of linked fate (Rogers 2006; Greer 2013; Thornton et al. 2013; Smith 2014; Brown 2015). In their national probability sample of first- and second-generation Black Caribbeans and multigenerational African Americans, Thornton et al. (2013) find significant “pan-ethnic links” between these subgroups and that Black Caribbeans do share a racial identity with African Americans while still maintaining strong ethnic and national ties. Social class status also affects black immigrants’ ethnic and racial identities in ways contradictory to the standard assumption that embracing a black identity is a sign of “downward assimilation.” Rather, identifying as “Black” evidences a strong belief in education as the most appropriate method for advancement (Bobb and Clarke 2001; Butterfield 2004).

New research on mixed-race and affluent blacks also highlights dissimilarities in racial self-concept and a diminished sense of collective fate (Lacy 2007; Rockquemore et al. 2009; Robinson 2011; Spencer 2011; Torres and Massey 2012). Structural factors, including market, neighborhood, and school segregation, also shape racial identity among black, Latino, and Asian subgroups and the development of a pan-ethnic identity (e.g., Denton and Massey 1989; Espiritu 1993; Massey and Denton 1993; DeSipio 1996; Crowder 1999; Vickerman 1999; Waters 1999; Kasinitz and Vickerman 2001; Chacko 2003; Okamoto 2006; Schildkraut 2005; Benson 2006; Rogers 2006; Lacy 2007; Quillian 2014). Irrespective of class status, the majority of black Americans still reside in segregated neighborhoods with concentrated disadvantage (Sharkey 2014; see also Lacy 2007; Charles 2006; Pattillo 2005). Segregation can, therefore, be a salient “contextual mechanism” that encourages intragroup solidarity and group consciousness among blacks as they strive to achieve collective goals (e.g., Quillian 2014, p. 405; see also Small 2009; Fischer and Massey 2000). Among black immigrant groups, housing market discrimination has a homogenizing effect on black identity. As a result of being confined to predominately black areas, some empirical evidence suggests that despite educational advantages, first- and second-generation African and Afro-Caribbean immigrants develop a strong racial group consciousness as a way to mobilize and collectively confront their shared structural and social realities with African Americans (e.g., Rogers 2006; Kim and White 2010; Greer 2013; Smith 2014).

Segregation concentrates poverty and has deleterious impacts on racial equality across a wide range of topics such as educational opportunities, mental and physical health, human capital acquisition, and credit markets (Massey and Denton 1993; Charles 2003; Massey and Fischer 2006; Pager and Shepherd 2008; Rugh and Massey 2010; Ananat 2011; Quillian 2012; Reskin 2012; Massey 2015). A growing body of psychological literature also suggests that residential segregation, class segregation, and environmental stressors (i.e., safety, violence, poverty) affect racial identity formation, racial pride, group consciousness, and self-efficacy among black adolescents and young adults (Corneille and Belgrave 2007; Byrd and Chavous 2009; Oyserman and Yoon 2009; McBride et al. 2011; Rivas-Drake and Witherspoon 2013). Consistent with the “neighborhood effects” research in sociology, the aforementioned research focuses on the economic and social outcomes of low-income and disadvantaged African Americans and does not consider multiple contexts of segregation (Quillian 2014)—neighborhood and school–as contributing to black identity formation in a heterogeneous young adult population.

Prior studies of black college students suggest that neighborhood segregation is typically considered a proxy for interracial contact and affects conceptions of blackness and racial group consciousness (Broman et al. 1989; Smith and Moore 2002; Massey et al. 2003; Sidanius et al. 2008; Charles et al. 2009; Torres 2009; Torres and Massey 2012). Massey et al. (2003) find that black NLSF students arrive at college with well-developed racial identities that are significantly related to pre-college neighborhood and school segregation. They find that 22 % of black students from segregated neighborhoods attended integrated high schools; another 28 % attended racially mixed high schools (Massey et al. 2003, p. 94). Black freshmen from the most segregated and disadvantaged neighborhoods espoused stronger black identities, felt closer to poor blacks, and expressed the most social distance from privileged whites and Asians, compared to black students with predominantly white and economically advantaged backgrounds (Massey et al. 2003, pp. 133–145). Our current work considers the dual contexts of pre-college segregation (neighborhood and school) and their potential effects on racial centrality and ideology among black NLSF respondents.

In short, experiencing neighborhood and/or school segregation as a child not only affects the likelihood of interracial interactions, but also organizes that child’s entire life in ways that may affect one’s racial identity and ideology. Indeed, Massey and Denton (1993) argue that the growth of hypersegregation was fundamental to the growth of a black politics and related ideologies built in and of segregated black communities. Gay (2004) finds a positive association between socioeconomic status and racial centrality among highly educated blacks living in predominately black areas. The “salience of race,” however, diminishes among blacks residing in economically advantaged areas (Gay 2004, p. 547). Gay’s findings refute Michael Dawson’s (1994) assertion that higher-status blacks willingly support the notion of linked fate and believe that racial group membership decides one’s socioeconomic mobility. Gay (2004) notes that neighborhood context matters for racial attitudes not as a proxy for social interaction, but rather one’s neighborhood’s quality “serve[s] as the basis for inferences about the larger social world and the individual’s place in it” (p. 559) and thus one’s racial attitudes. Unlike Dawson’s (1994) argument that higher-status blacks willingly support the notion of linked fate and believe that racial group membership decides one’s socioeconomic mobility, it appears that neighborhood context matters greatly for individual racial attitudes.

In sum, black racial identity is a much more complicated and nuanced concept than earlier studies of racial ideology and group consciousness suggest. Dawson’s concept of linked fate does not account for how contextual factors, including residential and school segregation, may shape group identity and self-concept among upper class blacks; Gay (2004) reveals that linked fate is neither static or universally accessible nor is it “unified across” social class (Dawson 2001, p. xii). The increasing demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual diversity within the black population requires us to pay careful attention to our conceptual understanding and measurement of racial identity, to ensure that it more accurately reflects the twenty-first-century realities of those coming of age in the “Post-Integration Era” (Simpson 1998).

Data and Methods

The National Longitudinal Survey of Freshmen (NLSF) is a uniquely rich survey for the study of black racial identity. The NLSF is the only nationally representative sample of black students at selective colleges and universities that includes measures of racial identity and captures the demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual diversity detailed previously. As such, it allows us to expand sociological research on black racial identity to the post-civil rights generation and to move beyond small, single-site studies that may be hampered by localized differences in black experiences or that lack data on other social identities (e.g., nativity status or class background) that may affect one’s racial identity. Moreover, these students represent the most elite segment of US blacks in higher education. Regardless of socioeconomic differences at matriculation, degree conferral from these elite institutions affords access to the upper echelons of mainstream American society, and these students represent the next generation of black American leaders in politics, business, and society more broadly.

We utilize aspects of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI) to conceptualize and measure the strength and character of black identity among this heterogeneous group. The MIBI was developed to measure racial identity in African American college students and adults (Sellers et al. 1997) and has been validated multiple times by other researchers (Cokely and Helm 2001). The MIBI represents a bottom-up approach (as opposed to the more standard top-down model) to capturing racial identity—respondents subjectively define what racial group membership means to them—and moves away from dichotomous models, allowing for the expression of a fluid racial identity based on both individual and collective beliefs (Sellers et al. 1997, 1998a, b). To our knowledge, the NLSF is the first large, nationally representative sample of black college students to employ the MIBI model. Our goal is to contribute to sociological considerations of black identity with a methodological approach that more accurately captures the complexity of black identity expression among an increasingly diverse US black population.

The NLSF tracks the academic and social experiences of approximately 4000 white, black, Latino/a, and Asian undergraduates attending 28 selective colleges and universities, including private institutions like Princeton University (the most selective institution in the sample with an acceptance rate of only 11 %), Miami University of Ohio (the highest acceptance rate at 79 %), as well as large, public universities like UC Berkeley and University of Michigan. The baseline survey, completed in the fall of 1999, was a face-to-face interview; subsequent interviews, completed during the spring terms of 2000, 2001, 2002, and 2003, were shorter, telephone interviews. Investigators used the racial/ethnic classifications adopted by the institutions themselves, which follow federal guidelines; however, during the baseline interview, respondents were also asked to classify themselves with respect to race, ethnicity, national origin, and birthplace. Sampling restrictions required that all participants be US citizens or legal residents. For additional details, see Massey et al. (2003, Chapter 2).

The analyses that follow draw on the first four waves of the study, but are restricted to student respondents who (1) screened into the study because they were classified as non-Hispanic black and (2) provided valid responses to all items in each of the three measures of racial identity, as well as the self-reported racial/ethnic classification and nativity status items. Of the original 1051 black student participants, 721 completed all items related to our outcome measures of black racial identity and provided complete information on their racial/ethnic self-classification. We use multiple imputations with the full sample before deleting any respondents with imputed values in any of the outcome measures (Von Hippel 2007). This strategy offers improved accuracy over listwise deletion (Allison 2001).

The NLSF includes a series of questions from the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI). Based on the Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity (MMRI), developed by Sellers et al. (1997), the MIBI is grounded in social identity theory (Stryker 1987), which posits that every person has several ordered identities (e.g., racial, gendered, ethnic, social class) and that within that hierarchy certain identities are more salient than others (Tajfel and Turner 1986; Stryker 1987). Social identity theory emphasizes the salience of group identity as it relates to the construction of individual identities and psychological well-being (Mead 1934; Lewin 1948).

The MIBI was designed to acknowledge a heterogeneous black American population and intragroup diversity in how same-race persons define themselves racially. Sellers et al. (1997) conceptualize racial identity as “the significance and qualitative meaning that individuals attribute to their membership within the black racial group within their self-concepts” (Sellers et al. 1998a, b, p. 23). As such, individuals can both assert a black identity and indicate what attitudinal and behavioral forms that identity takes. Because racial identity is not inherently more or less important than other social identities (e.g., gender, ethnicity, social class), it is analyzed within the “context of other identities” (1998a, b, p. 23.). Each MIBI subscale is scored separately, and no composite score is generated; the MIBI does not posit directionality or progression toward a specific and/or ideal identity. A primary strength of the MIBI is its emphasis on both the salience of race for one’s self-identity and the actual meanings ascribed to racial group membership.

Racial centrality is the degree to which one “normatively defines [oneself] with regard to race,” measuring whether or not race is a core aspect of one’s self-concept (the assertion of a black identity) (Sellers et al. 1997, p. 806). The Centrality subscale gauges the relevance of race for an individual and the priority that he/she places on race as part of their self-concept. The Ideology subscales capture perceptions that individuals have about black Americans and ideological meanings they attach to their racial identities.Footnote 2 We rely principally on two of the Ideology subscales—Assimilationist and Nationalist—to measure the ways in which black NLSF students perceive the parameters of membership in the racial group and how they believe blacks should act as a result. The assimilationist ideology emphasizes similarities between African Americans and the rest of US society; alternatively, a nationalist ideology is one that emphasizes the uniqueness of being of African descent. In contrast to research focused on the articulation of black group identity, the MIBI scales afford sociologists an opportunity to integrate racial self-concept as it relates to group identification and group consciousness, providing a more nuanced and accurate measure of racial identity than group identity and common fate measures do. We know of no quantitative sociological studies that consider multiple sources of intragroup heterogeneity—demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual—and measure multiple dimensions of black identity expression. Arguably, black NLSF students represent the next generation of black American leaders in politics, business, and society more broadly. We speculate that their education and somewhat privileged pre-adult integrative experiences will pave the way for many of them to become activists and community leaders, setting the tone and making salient decisions that will affect the black population more broadly (leading black politicians such as Corey Booker and Barack Obama have similar elite educational credentials). The expansion of black identity research in sociology is therefore necessary to keep pace with the demographic changes in the black American populace and black elite more specifically.

Descriptive Results

We begin with a detailed examination of a range of demographic, socioeconomic status, and social context characteristics, summarized in Table 1. The first panel of the table summarizes the demographic diversity of elite black college students. Monoracial/multigenerational native blacks are those students who self-identify as non-Hispanic black and US-born with two US-born parents (N = 473). First- and second-generation black immigrant students are those who identify either as non-Hispanic black or as “other” (and then filled in a national origin) and report being foreign-born (N = 59) or being US-born with at least one foreign-born parent (N = 109). Finally, mixed-race black students are those who self-identify as “mixed” (most wrote in detailed information regarding their racial heritage) and are US-born with two US-born parents (N = 80). Though Latino is traditional understood as an ethnic rather than a racial category, we include students who report themselves as mixed race with a Latino parent and interpret their own identities as such, as this identification as mixed race is also true for many, if not most, outside observers as well (Massey 2011). Excluded from our analyses is a subgroup of mixed-race students that also identifies as having immigrant origins—that is, either they themselves are foreign-born or one or both of their parents is foreign-born. Due to the small size of this subgroup, it was difficult to discern the primacy of mixed-race versus immigrant origins in these students’ conceptions of black identity, group consciousness, or self-concept. Fully 83 % of mixed-race black students have a white parent, roughly 10 % (9.6 %) report a Latino/a parent, and 6.4 % have an Asian parent. Together, mixed-race and immigrant black students account for just over one-third of black students in the NLSF, and both are substantially overrepresented relative to the US black population as a whole.

We also considered the possibility that region of origin might play a role in the black racial identities of black immigrant and second-generation students as nearly half of the immigrant students originate from the Caribbean (mostly from Jamaica, Haiti, and Trinidad and Tobago) and most of the remaining students originate from Africa (primarily Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya); however, a careful analysis revealed that region of origin was not a significant factor. We do find important differences by generational status. For these reasons, and to maintain as many degrees of freedom as possible (given the relatively small number of foreign-born black students in particular), we have excluded region of origin from our multivariate analyses. Note also that men are underrepresented among the ranks of black students at elite institutions, comprising just over one-third of the group. Incidentally, this pattern is fairly consistent across the other demographic subgroups and is consistent with national trends at top-ranked colleges and universities (Journal of Blacks in Higher Education 2006).

A variety of other sociodemographic characteristics may also influence dimensions of black racial identity, and these traits fill out the middle panel of Table 1. Unsurprisingly, black NLSF students tend to come from higher socioeconomic status backgrounds than most black Americans. More than half of the black students in our sample report growing up in two-parent households; nearly three quarters of our sample (73.5 %) have at least one college-educated parent. In fact, over two-fifths of the sample has a parent with at least one advanced (Masters or higher) degree. We code parental education as a series of dummy variables based on the highest degree obtained by at least one parent. Nearly three-fourths of the respondents are from families that own their homes (73.3 %), almost as many have parents employed in professional or managerial occupations (68.8 %), and more than a quarter report family incomes over $100,000/year. The family structure and parental educational attainment of black NLSF respondents is markedly different from that found in the US black population as a whole, where just slightly over one-third of blacks (34 %) report two-parent households, and even fewer have parents with post-secondary educational attainment. Black students at selective institutions are more than twice as likely to have at least one college-educated parent as is true in the US black population (13.4 %) and 14 times more likely than US black youth (2.75 %) to have at least one parent with an advanced degree. In addition, 29 % of US blacks are employed in management, professional, and related occupations and just 9.4 % have annual earnings of $100,000 per year or more (DeNavas-Walt et al. 2013; National Center for Education Statistics 2010; Child Trends Databank 2015; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2011).

Despite the overrepresentation of socioeconomic privilege among NLSF blacks, it is nonetheless important to note that more than one quarter of these students (26.4 %) will be the first in their immediate families to graduate with a 4-year college degree. Similarly, just over 30 % indicate that neither parent is employed in a professional/managerial occupation, and nearly two-fifths (39.3 %) report family incomes of less than $50,000 per year. Thus, while it is true that black NLSF students are a socioeconomically advantaged group compared to the US black population writ large, it is also true that a sizeable minority of NLSF black students have socioeconomic backgrounds that are similar to larger population of blacks in the USA.

There is substantial variation across subgroups of black NLSF students not reported here. Charles et al. (2008) highlight a significant African advantage with respect to family structure (70 % of African-origin students are from two-parent households, compared to roughly half of monoracial natives, Caribbean-origin students, and mixed black students) and parental education (among African-origin students, nearly 40 % of mothers and almost 70 % of fathers have advanced degrees, compared to between one quarter and one-third of mothers and 24–31 % of fathers for other subgroups). African-origin and mixed black students report the highest family incomes (approximately $80,000/year, on average), and monoracial/multigenerational and Caribbean-origin blacks are most likely to report family incomes below $50,000/year. Contrary to their higher levels of education and income, however, African-origin students report lower levels of homeownership (62 %), fully 10–15 % below other subgroups (Charles et al. 2008, p. 251).

The bottom panel of Table 1 summarizes the neighborhood and school characteristics—the social contexts—of elite black college students. Racial segregation is measured as racial isolation, or the average combined percent minority (black and Latino) in respondents’ neighborhoods and schools, self-reported for ages 6, 13, and 17 and converted to a 0–10 scale. “Neighborhood” is defined as a three-block radius surrounding respondents’ homes. A predominantly white experience is a neighborhood that is no more than 30 % black or Latino; an integrated experience is greater than 30 % and no more than 70 % black or Latino, and a segregated minority experience is over 70 % black and Latino. To gauge the accuracy of self-reported neighborhood context, respondents’ home addresses were geocoded using 2000 Census tract data for comparison with respondent self-reports. Black NLSF respondents’ self-reports were highly accurate, yielding a correlation of 0.83 with the closest census year. Since the neighborhood boundaries used in the NLSF are significantly smaller than census tracts, these estimates offer a conservative bias to the analysis (Massey and Fischer 2006, p. 6).

Nearly two-fifths of black NLSF students hail from neighborhood and school contexts that are predominantly white, and slightly more report racial integrated neighborhood and school contexts. Nearly one quarter, however, report growing up in highly racially segregated neighborhoods and schools. Some important subgroup/regional differences are worth noting: 60 % of mixed black students and half of African-origin students come from predominantly white contexts, compared to fewer than one-third of monoracial, multigenerational native and Caribbean-origin black students. In our regression models, we convert categories to a 0-to-10 scale of racial isolation (where 0 means no blacks or Latinos in one’s school or neighborhood and 10 would mean an entirely black and/or Latino school and neighborhood experience); respondents report a somewhat mixed experience on average (3.93 or 39.3 %).

A second aspect of social context—and an important corollary of racial segregation—is the degree to which individuals are exposed to violence and social disorder. These more specific structural characteristics of black NLSF students’ neighborhoods and schools, we have argued, might influence their self-reported racial identities in meaningful ways. To glean these experiences, all respondents were asked about their exposure to various kinds of social disorganization in their neighborhoods and schools during childhood, using a 0-to-10 scale in which zero indicates no exposure and 10 indicates constant exposure. For our purposes, we take the average scores across all items, which are weighted for severity (for details, see Massey et al. 2003, Appendix Tables B5–8). Note that, on average, students report low or infrequent exposure to violence and social disorder while growing up; however, it is also the case that students from more segregated minority neighborhoods and schools have decidedly more exposure to social disorganization (Massey et al. 2003). We tested for differences in exposure to violence and social disorder by immigrant status and region of origin, but found no statistically significant differences.

The substantial intragroup diversity detailed in Table 1 sets the stage for our examination of three dimensions of elite black students’ racial identity, measured during their junior year of college (NLSF Wave 4). The first subscale, racial centrality (α = 0.81), is the average of eight items measuring the degree to which being black/African American is a core component of respondents’ self-identity. The other two subscales, assimilationist ideology (α = 0.76) and nationalist ideology (α = 0.79), are the averages of 9 items each, and measure adherence or subscription to the two cultural/political ideologies most commonly considered to guide the attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors of the black population in the USA. Historically, these worldviews have been treated as incompatible or, at best, opposite ends of a single ideological continuum (e.g., Malcolm 1963). It is also often assumed that those blacks espousing an assimilationist ideology are less “black identified” and would, as such, have lower racial centrality. Following the same logic, blacks espousing a clearly nationalist ideology would exhibit strong racial centrality. However, some scholars criticize the assumption that assimilation and nationalism are two ends of a single continuum, and therefore, we should not expect such clear and direct association with racial centrality for either (Brown and Shaw 2002; Masuoka and Junn 2008; McClain et al. 2009; Shelton and Emerson 2010).Footnote 3

Racial Centrality

It is immediately evident that black students at highly selective colleges and universities do not neatly conform to a “postracial” model in which race is incidental or peripheral to their sense of self. On average, black NLSF students indicate that being black is quite central to their overall self-concept. Of the eight items in the racial centrality scale, four have mean values above 7 on a 0-to-10 scale, where 0 means race does not matter at all and 10 suggests that race is of utmost importance. Students report a largely internal and character-driven importance of black identity; being black is, for example, “important to what kind of person” they are (7.93), but believe race has less impact on their social relationships (5.51) or how they feel about themselves (5.67).

Perhaps most notable is that the only subscale item that has a mean value below the midpoint of the scale (4.54) was the measure of “linked” or “common fate” that has often been used as an indicator of racial identity in social science research (Massey et al. 2003; Charles 2006; Bobo et al. 2012). Both on average and compared to the other subscale items, black students are least inclined to believe that their individual destinies are “tied to the destiny of other African Americans.” Taken together, it appears that racial centrality is not simply the degree to which individual blacks perceive their fate as linked to that of the larger black population. Overall, black NLSF students express strong tendencies toward group membership, as well as a sense of individualism. The mean value for our overall measure of racial centrality—a highly reliable index that is the average of scores on each of the 8 items—reflects a moderately high degree of racial centrality (6.53).

Assimilationist Ideology

The second panel of Table 2 summarizes responses to items measuring assimilationist ideology. Consistent with the racial centrality subscale items and the overall scale, responses are measured on a 0-to-10 scale, with higher values indicating increasing assimilationist attitudes; the overall scale is the average of the 9 individual items. Due to the highly selective nature of the respondents—all are attending very selective colleges and universities—it comes as no surprise that mean values for each of the nine items are always above the midpoint (5.0) and that the mean overall index score is nearly seven out of a possible ten points (6.93).

Though not especially surprising given the highly selective nature of our sample, it is nonetheless often assumed that an assimilationist worldview is inconsistent with the relatively high degree of racial centrality also exhibited by black NLSF students. Respondents are nearly unanimous in asserting that blacks/African Americans should “feel free to interact socially with whites” (9.11). Three other items also have mean values well above seven, suggesting that most black NLSF students believe that members of their group should “be full members of the political system” (7.80), “work within the system to achieve political/economic goals” (7.46), and “strive to integrate all segregated institutions” (7.42). This assimilationism, however, is not a demand for integration above all else, as students are much less likely to believe that blacks should “attend white schools to learn to interact with whites” (5.16). This assertion yields the lowest mean score in the assimilationist subscale, yet still suggests a moderate level of support. Overall, responses support a relatively strong and uniform assimilationist ideology among these students; the mean score for the assimilationist ideology scale is 6.93.

Nationalist Ideology

A close examination of responses to the MIBI items measuring nationalist ideology casts further doubt on both simplistic understandings of black racial identity and assertions of an emergent postracial black identity. Admittedly, the mean across all nine items in the subscale is only 4.51—roughly two full points lower than the assimilationist ideology subscale. On its face, the relative difference suggests a tendency among these upwardly mobile young black students to eschew a nationalist worldview.

As highlighted in the bottom panel of Table 2, the nationalist ideology subscale reveals two distinct types of nationalism: a cultural nationalism that does not preclude interaction with other racial groups and is strongly supported by all black students and a political, separatist nationalism that garners very little support among black NLSF students. Our findings contradict previous MIBI studies of black college students that tend to reveal a strong separatist/nationalist ideology among respondents that is negatively associated an assimilationist worldview (see Sellers et al. 1997, 1998a, Shelton and Sellers 2000). These prior studies, however, rely on smaller samples (<500 respondents), and results are not typically disaggregated across multiple sociodemographic dimensions—i.e., ethnicity, nativity, gender, and social class. Our results support Brown and Shaw’s (2002) assertion that discussions of black nationalism conflate two distinct subsets of nationalism, the more separatist, political nationalism that is stronger among less affluent blacks and black men.

Black students enrolled in elite colleges and universities generally reject more traditional, separatist beliefs about interracial marriage (2.02), the importance of Afrocentric values (3.86) and racially separate schools (3.25), and even the need to organize into a separate political force (3.19). These students similarly tend to reject pessimistic beliefs about whites’ trustworthiness (2.34) or the future of race relations (2.93). The low level of support across individual measures of political nationalism yields an overall mean value of just 2.93 on a 0-to-10 scale. Alternatively, they express a relatively high degree of cultural nationalism—both in absolute terms and relative to the other subscales. The overall mean for cultural nationalism is 7.78 (the highest for the dimensions of black identity considered here) and reflects favorable attitudes toward surrounding black children with African American culture (7.87), patronizing black-owned businesses (6.93), and being conversant in African American history (8.55).

As a whole, results for measures of nationalist ideology offer several meaningful insights. First, contrary to expectations for this subscale, we find that nationalist ideology is best understood for these students as consisting of two distinct types: cultural and political. As anticipated given the highly selective subset of blacks under study here, there is little adherence to a politically nationalist ideology. There is, however, strong support for cultural nationalism. Indeed, elite black college students exhibit greater adherence to this strain of black nationalism than they do to assimilationist ideology, on average. Finally, elite black college students adhere simultaneously to assimilationist and (culturally) nationalist ideologies, challenging (1) assertions of upwardly mobile blacks as postracial, as well as (2) traditional notions of black racial ideology as an “either/or” proposition.

Bivariate and Multivariate Results

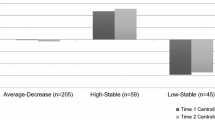

We now turn to analyses aimed at understanding the degree to which the personal characteristics of elite black college students influence the strength and character of their racial identities. The outcomes of interest are the four dimensions of racial identity—centrality, assimilationist ideology, cultural nationalism, and political nationalism—introduced in the previous section. Specifically, we examine the influence of the diverse origins and backgrounds of elite black college students along the dimensions of their (1) demographic characteristics—racial classification, nativity status, and sex, (2) socioeconomic characteristics—family structure, parental education and occupation, family income and housing tenure, and (3) neighborhood and school contexts—experience of segregation and exposure to violence and social disorder. As our primary focus is on deviation from the assumed “typical” black student at these schools (native to the USA; from a lower SES status; from a segregated neighborhood), we present results from a series of two-sample t tests comparing each subgroup to that stereotypical black experience. This has the additional benefit of avoiding F test-based analyses (e.g., ANOVA), for which multiple imputation can lead to inaccurate tests of statistical significance. In general, ANOVA and t test results are largely consistent. These results are summarized in Table 3.

Demographic Characteristics and Racial Identity

The top panel of Table 3 summarizes mean scores for racial centrality, assimilationist ideology, and cultural and political nationalism across demographic characteristics. Results reveal substantial intragroup variation across the various racial classifications and nativity statuses considered here. Differences are greatest for racial centrality, with a clear difference between monoracial and mixed-race black NLSF students. Monoracial, multigenerational native blacks exhibit the highest mean score on this dimension (6.86); first- (6.25, p < 0.05) and second-generation (6.35, p < 0.01) immigrant blacks score slightly, lower on average. Mixed-race black NLSF students—particularly those with a white parent—report substantially lower levels of racial centrality. Among black/white mixed students, the average racial centrality score is 5.01 (p < 0.001); the mean value for centrality is among mixed-race blacks with a Latino or Asian parent is more similar to that for immigrant blacks (6.12, p < 0.05). That mixed-race black express the lowest average level of racial centrality is consistent with their preference to self-identify as mixed race (as opposed to “black”), as well as likely differences in their lived experience of race. Our findings align with qualitative and anecdotal narratives on self-identified black/white mixed-race young adults that discuss a preference among some to embrace a “mixed” identity over an exclusively black one, racial socialization of children in mixed-race families, as well as the effects of phenotype on self-concept and racial categorization (Root 1996; Harris and Simms 2002; Roccas and Brewer 2002; Rockquemore et al. 2009; Khanna and Johnson 2010).

Differences among black NLSF students on assimilationist ideology, summarized in the second column of Table 3, are significantly smaller and statistically less powerful than those for racial centrality. This is understandable, given that these students have successfully matriculated at some of the country’s most prestigious colleges and universities, which on its own signals allegiance to integrationist/assimilationist beliefs about how best to achieve upward mobility in the twenty-first-century USA. Monoracial, multigenerational native blacks report the lowest average assimilationist ideology score (6.81), and interestingly, mixed-race students with a Latino or Asian parent are not significantly different from this group, on average, with a mean centrality score of 6.83. Once again, it is mixed-race blacks with a white parent who are most different from monoracial natives, expressing the highest average assimilationist ideology (7.27, p < 0.05). In between are first- (7.20, p < 0.05) and second-generation black immigrants (7.10, p < 0.10), respectively. Mean values for immigrant blacks are similar to many of the Afro-Caribbean young adults in Waters (1999) sample who acknowledge their collective place within the racial hierarchy and the resultant closeness to their multigenerational African American peers.

The third and fourth columns of Table 3 summarize intragroup differences in cultural and political nationalism, respectively. Results for cultural nationalism are generally more consistent with those for centrality. That is, monoracial native blacks have the highest average score (8.07), and mixed-race, black/white black NLSF students the lowest, and by a substantial margin (6.41, p < 0.001). Mixed-race blacks with a Latino or Asian parent (7.33, p < 0.05) and second-generation immigrant black students (7.52, p < 0.01) fit neatly between these two extremes, while foreign-born black immigrants do not differ significantly from multigenerational natives on this dimension of black identity.

There is little support for political nationalism across categories of racial classification and nativity status. While monoracial native blacks score higher than all other subgroups, on average (3.02), this average score is well below the midpoint for the scale, and less than half the value of mean scores on all other dimensions for all subgroups. The only group that differs significantly from monoracial native blacks is—perhaps predictably—mixed-race blacks with white parents (2.19, p < 0.01). Finally, men and women differ significantly only twice: On average, black men express marginally less racial centrality than women (6.37, p < 0.10), but more cultural nationalism (7.94, p < 0.01).

Socioeconomic Status and Racial Identity

The second panel of Table 3 summarizes mean values for our racial identity measures across socioeconomic status characteristics. Social class characteristics exert relatively little influence on the dimensions of black racial identity considered here. Nonetheless, a few interesting findings emerge.

The only social class characteristic that significantly influences the centrality dimension is having college-educated parents who did not earn advanced degrees. Blackness is less central for these students, on average (6.07, p < 0.001), compared to those whose parents are without a college degree. Alternatively, three social class characteristics appear to influence adherence to an assimilationist ideology. Residing in a traditional, two-parent household (7.04, p < 0.05), having parents with high occupational status (7.01, p < 0.05) and/or who are homeowners (7.04, p < 0.01) significantly increases scores on this ideological dimension.

Socioeconomic status differences matter even less for adherence to either a culturally or a politically nationalist ideology. Black students whose parents have no more than a bachelor’s degree (7.51, p < 0.001) express less cultural nationalism than those whose parents have no more than a high school diploma. And, finally, the generally low support for a politically nationalist worldview among elite black college students exists largely irrespective of social class background, with two small exceptions that are wholly unsurprising: black students from two-parent households (2.81, p < 0.05) and those whose parents have high-status jobs (2.86, p < 0.10) express significantly less political nationalism than their respective reference groups. On the whole, it seems that socioeconomic status characteristics play a relatively small role in shaping the racial identities of elite black college students.

Social Context and Racial Identity

The bottom panel of Table 3 summarizes the extent to which childhood neighborhood and school contexts shape dimensions of black racial identity. It is immediately evident that the experience of structural inequality matters for all dimensions of black racial identity, yet these associations are not identical across the four dimensions. Bivariate results indicate that experiencing segregation is associated with higher racial centrality, as the difference between growing up in a predominantly minority experience and a predominantly white experience is highly statistically significant (p < 0.001) and equivalent to a shift of over half a point on the scale (6.94 vs. 6.41). An even larger association occurs with regard to cultural nationalism, as it falls monotonically from 8.27 for students from segregated backgrounds to 7.88 (p < 0.05) for students from integrated backgrounds to nearly a full point lower for students from predominantly white backgrounds (7.49, p < 0.001).

Exposure to violence and social disorder during childhood is more consistently influential, revealing statistically significant differences across three of the four dimensions of black identity, all in a manner consistent with those for racial segregation. Students from segregated backgrounds report the highest scores for centrality and both forms of nationalism and the lowest score for assimilationist ideology. In three of the scales, the difference between experiencing high levels of disorder and violence and low levels is nearly a full point on the scale (for political nationalism, because the average is so low, the effect is only about 0.6 points). Additionally, compared to students with high exposure to disorganization, moderate exposure to social disorganization in neighborhoods and schools during childhood is associated with a greater commitment to assimilationist ideology (6.97, p < 0.01) and less adherence to cultural nationalism (7.78, p < 0.05).

Together, these preliminary results highlight the importance of social context for shaping dimensions of black racial identity. Attention now turns to a consideration of the relative importance of various demographic, socioeconomic, and contextual characteristics for understanding dimensions of black racial identity.

Intragroup Heterogeneity and Dimensions of Black Identity

Prior research details the diverse social backgrounds of native, immigrant, and mixed-race elite black college students (Massey et al. 2007; Charles et al. 2009), and the simultaneous consideration of various aspects of intragroup heterogeneity sheds additional light on findings offered previously. For our final set of analyses, summarized in Table 4, we explore the relative influence of each set of factors on racial centrality, assimilationist, and (cultural and political) nationalist ideologies among elite black college students.

First, the hierarchies of racial classification and nativity status noted previously persist even when models account for social background characteristics and neighborhood and school contexts. For example, in the model for racial centrality, monoracial, multigenerational native blacks express the strongest racial centrality. Blackness is least central to the identities of mixed-race blacks with a white parent (−1.66, p < 0.001), but mixed blacks with a Latino or Asian parent are not much different (−1.13, p < 0.05). In between these extremes are immigrant blacks, whose positions remain in line with theories of immigrant acculturation (Waters 1999; Charles 2006), whereby the second generation resembles monoracial natives (−0.43, p < 0.05) more than their foreign-born counterparts do (−0.59, p < 0.05). When social background and contextual characteristics are excluded, changes in coefficient size and statistical power are relatively small.

Controlling for social background and contextual characteristics does little to alter the patterns of racial ideology detailed in Table 3. Net of other factors, all subgroups of blacks adhere more intently to an assimilationist worldview than monoracial natives (again, with the exception of mixed blacks with a white parent), but are less inclined toward cultural nationalism than monoracial native blacks (again, with the exception of first-generation immigrants). And, only mixed-race, double-minority blacks express significantly less political nationalism than monoracial natives, net of background and context.

Second, controlling for racial classification/nativity status and social context differences seems to enhance gender differences across identity dimensions. Net of other factors, black men exhibit slightly less racial centrality (−0.27, p < 0.10) and are more likely to adhere to an assimilationist worldview (0.24, p < 0.05) compared to black women; the gender difference in cultural nationalism declines by roughly one-tenth of one point (−0.50, p < 0.001). When other factors are accounted for, the influence of household type and other social background characteristics remain largely unchanged compared to those reported in Table 3.

Finally, controlling for racial classification, nativity status, and social background characteristics clarifies and reinforces the importance of neighborhood and school contexts in the racial identities of elite black college students. Net of other factors, exposure to violence and social disorder exerts a substantial influence on all four dimensions of black racial identity, and the experience of racial isolation is consequential for both forms of nationalist ideology (the significant interaction between the racial isolation and exposure to violence and social disorder for understanding cultural nationalism also persists). Accounting for other aspects of heterogeneity, exposure to social disadvantage increases racial centrality and both types of nationalism, and decreases adherence to assimilationist beliefs.

In sum, these results strongly suggest that differences in racial classification and nativity status, and racial isolation and exposure to violence and social disorder are particularly influential for shaping dimensions of racial identity among elite black college students. In comparison with the influence of these factors, sociodemographic characteristics matter very little, confirming the bivariate comparisons presented earlier.

Discussion and Conclusion

Racial identity is a fluid concept defined in part by societal ideologies and structures that either facilitate or constrain opportunities. For much of US history, stark and overt inequalities led to an oversimplified, either/or dichotomy with regard to both racial and political ideologies (e.g., black or not black, assimilationist or nationalist). This oversimplification has always been problematic; however, increasing heterogeneity within the US black population—most notably through immigration, interracial births, and an expanding middle class—has laid bare the inaccuracies and limitations of those shorthand notions of blackness in the twenty-first century. Our analyses highlight black racial identity as complex and multidimensional, separate and apart from the challenges of racial/ethnic classification (e.g., monoracial or mixed race, foreign-born, second-generation, or multigenerational native). Importantly, we distinguish racial self-identification from its cultural and political performance, which may be associated with a variety of other social background characteristics (Bettie 2000) that “interact with one’s racial identity to structure life choices” (Cohen 1999, p. 347) and alter one’s sense of linked fate. In general, those characteristics do not alter one’s racial identity.

Our findings indicate that racial centrality is not simply the degree to which our respondents perceive their fate is linked to that of other blacks. These elite black college students express a strong sense of individualism and place less emphasis on the importance of race for their social relationships or how they feel about themselves. Importantly, those racial identities are associated with mixed-race heritage, racial segregation, and immigrant status. Political scientist Candis Watts Smith (2014) calls this a “diasporic consciousness” in which self-concept and group consciousness dynamically interact for black immigrants. Smith argues that this conceptualization promotes a thorough recognition of race as a superordinate identity with a homogenizing effect on black immigrants’ perceive themselves collectively as “in the same boat” as other blacks “in the struggle against racial inequality,” while also holding contrasting beliefs and political interests tied to their immigrant and/or ethnic identities (2014, pp. 6–7). Our findings support the existence of a diasporic consciousness among black college students; immigrant background was associated with a more assimilationist, less nationalistic identity, but one that still privileged race as important for individual self-identity. Our findings also suggest that mixed-race heritage, racial segregation and its associated disadvantages, and social background characteristics are also important for understanding diasporic consciousness and assist in understanding the situational character of racial identity among an increasingly diverse black elite. For these elite black collegians, racial group consciousness cannot be equated with racial self-concept; instead, our findings indicate that individual identity is shaped by students’ conceptions of the racial hierarchy and their location within it.

Our findings show that net of other sociodemographic characteristics, racial segregation and exposure to violence and social disorder as directly associated with racial group consciousness and self-concept. Black students from the poorest and most segregated pre-college contexts were also the most likely to espouse cultural and political nationalist ideologies and lowered assimilationist tendencies. Exposure to violence and disorder, but not segregation, also is associated with greater racial centrality. In general, structural inequalities are directly linked to individual understandings of racial identity; however, that process is more complicated than a simple connection between segregation and racial identity. The experience of concentrated disadvantage associated with racial segregation—not racial segregation per se—strengthens racial centrality and nationalist ideologies and weakens assimilationist beliefs. While racial segregation significantly impacts political and cultural commitments to blackness, it does not make a black identity more central for black students, nor does it negate interest in integration.

There are, however, some limitations to our results. First, the NLSF includes only a subset of the full MIBI schema and may not capture other variations in ideology or racial regard (Sellers et al. 1998a, b; Shelton and Sellers 2000). Second, these data were collected before symbolically important moments like the election of Barack Obama as President, the [c]overt racism of the Tea Party (Hutchinson 2013), the #BlackLivesMatter movement, and the disparate impact of the Great Recession (Brooks and Manza 2013), that may have impacted these respondents’ racial identities in important ways as they grew older. More recently, the 2012 presidential election cycle has been touted as one of the most racially charged in recent memory, and this too could impact black identity among elite blacks in important ways. There might also be differences for younger cohorts of black students. Our analyses represent an initial consideration of the complexity of black racial identity and the factors that might help us better understand that complexity. Future research will consider whether and how these findings shape elite black college students’ racial and social attitudes, and the elite college experience more generally.

In the contemporary moment, a more nuanced and multidimensional understanding of black racial identity and the dynamic interplay between and among racial classification, racial identity, and racial ideology is critical for advancing sociological research on the status of blacks in the USA. Despite their convergence at some of the nation’s most elite colleges and universities, this new generation of elite blacks varies in both the centrality and expression of their racial identities. The intensity and ideological expressions of blackness among this elite subset of US blacks appears tied to racial/ethnic ancestry and to prior experiences of structural inequality. Elite black college students proudly proclaim the centrality of race to their identities, simultaneously embrace assimilationist and culturally nationalist ideologies, and rebuke black nationalist politics problematizing dichotomizing proxies for racial identity that focus on social distance or linked fate alone. Contrary to lay understanding and prior social science research, we find that traditional social class characteristics are remarkably non-influential in both bivariate and multivariate analyses. In short, contrary to Cohen’s (1999) “raced, but not racial” black leaders, our respondents are raced and culturally (if not politically) racial.

Finally, we argue that these students are a uniquely important subset of the US black population—more diverse than the black population in general—disproportionately integrated into predominantly white neighborhoods, workplaces, and organizations, and be positioned in influential leadership roles. However, the fact of their high aspirations and achievements suggests the possibility that their racial identities may be uniquely optimistic and/or complicated by their early successes. To the degree that these black students (and others like them) will find themselves in high-status positions, future research should investigate whether and how navigating these spaces impacts any or all of the dimensions of racial identity examined here, the degree to which the patterns detailed here persist over time, and whether or not the intragroup diversity leads to policy preferences or political attitude differences or the largely consistent racial identities trump that diversity. Nonetheless, our results confirm a black racial identity that is—and has always been—complex and multidimensional, influenced by both individual and structural factors; it is not in crisis, nor is it easily subjected to simplistic policing of racial authenticity, especially in light of increasing (and increasingly visible) intraracial heterogeneity. Rather, it is a structured identity that warrants serious consideration in sociology.

Notes

Throughout the paper, we use the terms “black,” “Black,” “Black American,” and African American interchangeably to signify those individuals in our sample and in the US context more broadly, who self-identify racially as Black (or acknowledge their parents/relatives as being Black) and have ancestral origins in Africa.

Due to time constraints and an evaluation of the results of studies using the MIBI, the NLSF team opted not to include the regard scale or two of the ideology scales. Regard is based on prior research on collective self-esteem and is one's affective, evaluative judgment of one's race. In the Multidimensional Model of Racial identity (the theory on which the MIBI is designed), regard is seen as mediating the relationship between centrality and specific behaviors and is correlated with centrality. The assimilationist and nationalist ideology scales are moderately correlated with the unused ideology scales and capture the main contrasts in black political ideologies in the USA.

For complete information on question wording, please refer to the wave 4 codebook for the National Longitudinal Survey of Freshmen (http://nlsf.princeton.edu).

References

Allen, R. L., Dawson, M. C., & Brown, R. E. (1989). A schema-based approach to modeling an African American racial belief system. American Political Science Review, 83(2), 421–439. doi:10.2307/1962398.

Allen, R. L., & Hatchett, S. (1986). The media and social reality effects: Self and system orientation of blacks. Communication Research, 13(1), 97–123.

Allison, P. D. (2001). Missing data (Quantitative applications in the social sciences). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ananat, E. O. (2011). The wrong side(s) of the tracks: The causal effects of racial segregation on urban poverty and inequality. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(2), 34–66.

Banks, W. M. (1976). White preference in blacks: A paradigm in search of a phenomenon. Psychological Bulletin, 83(6), 1179–1186.

Benson, J. (2006). Exploring the racial identities of black immigrants in the United States. Sociological Forum, 21, 219–247.

Bettie, J. (2000). Women without class. Chicas, cholas, trash, and the presence/absence of class identity. Signs, 26(1), 1–35.

Blauner, R. (1972). Racial oppression in America. New York: Harper and Row.

Bobb, V., & Clarke, A. Y. (2001). Experiencing success: Structuring the perception of opportunities for West Indians. In N. Foner (Ed.), Islands of the city: West Indian migration to New York (pp. 216–236). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bobo, L. D. (2001). Racial attitudes and relations at the close of the twentieth century. In M. Smelser, W. J. Wilson, & F. Mitchell (Eds.), America becoming: Racial trends and their consequences (pp. 262–299). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Bobo, L. D., & Charles, C. Z. (2009). Race in the American mind: From the Moynihan Report to the Obama candidacy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 621(1), 243–259.

Bobo, L. D., Charles, C. Z., Krysan, M., & Simmons, A. (2012). The real record on racial attitudes. In P. Marsden (Ed.), Social trends in American life: Findings from the General Social Survey since 1972. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Broman, C. L., Neighbors, H. W., & Jackson, J. S. (1988). Racial group identification among black adults. Social Forces, 67(1), 146–158.

Broman, C. L., Neighbors, H. W., & Jackson, J. S. (1989). Sociocultural context and racial group identifcation among black adults. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale, 2(3), 367–378.

Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2013). A broken public? Americans’ responses to the Great Recession. American Sociological Review, 78(5), 727–748. doi:10.1177/0003122413498255.

Brown, W. O. (1931). The nature of race consciousness. Social Forces, 10(1), 90–97.

Brown, V. (2015). In solidarity: When Caribbean immigrants become black. NBC News/NBC BLK. Retrieved from (http://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/solidarity-when-caribbean-immigrants-become-black-n308686). Accessed July 20, 2015.

Brown, R. A., & Shaw, T. C. (2002). Separate nations: Two attitudinal dimensions of black nationalism. Journal of Politics, 64(1), 22–44. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.00116.

Bryce-Laporte, R. L. (1972). Black immigrants: The experience of invisibility and inequality. Journal of Black Studies, 3(1), 29–56.

Butterfield, S. (2004). Challenging American conceptions of race and ethnicity: 2nd Generation West Indian immigrants. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 24(7–8), 75–102.

Byrd, C. M., & Chavous, T. A. (2009). Racial identity and academic achievement in the neighborhood context: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 544–559. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9381-9.

Chacko, E. (2003). Identity and assimilation among young Ethiopian immigrants in metropolitan Washington. The Geographical Review, 93(4), 491–506.

Charles, C. Z. (2003). The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 167–207.

Charles, C. Z. (2006). Won’t you be my neighbor? Race, class, and residence in Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Charles, C. Z., Fischer, M. J., Mooney, M. A., & Massey, D. S. (2009). Taming the river: Negotiating the academic, financial, and social currents in selective colleges and universities. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Charles, C. Z., Torres, K. C., & Brunn, R. J. (2008). Black like who? Exploring the racial, ethnic, and class diversity of black students at selective colleges and universities. In C. A. Gallagher (Ed.), Racism in post-race America: New theories, new directions (pp. 247–266). Chapel Hill: Social Forces.

Child Trends Databank. (2015, March). Indicators on children and youth. Appendix 1—Living arrangements of children under 18 years old, percentages by race and Hispanic origin 1: Selected years, 1960–2014. Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/07/59_Family_Structure.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C. (2013, September). Current population reports, P60-243. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2011. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p60-245.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

Chong, D., & Rogers, R. (2005). Racial solidarity and political participation. Political Behavior, 27(4), 347–374. doi:10.1007/s11109-005-5880-5.

Cohen, C. J. (1999). The boundaries of blackness. AIDS and the breakdown of black politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cokely, K. O., & Helm, K. (2001). Testing the construct validity of scores on the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 34(2), 80–95.

Corneille, M. A., & Belgrave, F. (2007). Ethnic identity, neighborhood risk, and adolescent drug and sex attitudes and refusal efficacy: The urban African American girls’ experience. Journal of Drug Education, 37, 177–190.

Cornell, S. E., & Hartmann, D. (1998). Ethnicity and race: Making identities in a changing world. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Crowder, K. D. (1999). Residential segregation of West Indians in the New York/New Jersey metropolitan area: The roles of race and ethnicity. International Migration Review, 33(1), 79–113.

Davis, T. J, Jr. (2011). Black politics today: The era of socioeconomic transition. New York: Routledge (Series on Identity Politics).

Dawson, M. C. (1994). Behind the mule: Race and class in African American politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dawson, M. C. (2001). Black visions. The roots of contemporary African American ideologies political ideologies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Demo, D., & Hughes, M. (1990). Socialization and racial identity among black Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly, 53(4), 364–374.

Denton, N., & Massey, D. (1989). Hypersegregation in U.S. metropolitan areas: Black and Hispanic segregation along five dimensions. Demography, 26, 373–392.

DeSipio, L. (1996). More than the sum of its parts: The building blocks of a pan-ethnic Latino Identity. In W. C. Rich (Ed.), The politics of minority coalitions: Race, ethnicity, and shared uncertainties (pp. 177–189). Westport: Praeger.

Drake, S., & Clayton, H. (1962). Black metropolis: A study of negro life in a northern city. New York: Harper Torch Books.

Eggerling-Boeck, J. (2002). Issues of black identity: A review of the literature. African American Research Perspectives, 8, 17–26.

Espiritu, Y. (1993). Asian American panethnicity: Bridging institutions and identities. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Ferguson, E. A. (1938). Race consciousness among American negroes. Journal of Negro Education, 7(1), 32–40.

Fischer, M. J., & Massey, D. S. (2000). Residential segregation and ethnic enterprise in U.S. metro-politan areas”. Social Problems, 47(3), 408–424.

Gatewood, W. B. (2000). Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880–1920. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

Gay, C. (2004). Putting race in context: Identifying the environmental determinants of black racial attitudes. American Political Science Review, 98(4), 547–562. doi:10.1017/S0003055404041346.

Gordon, M. (1964). Assimilation in American life. The role of race, religion, and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

Greer, C. M. (2013). Black ethnics: Race, immigration, and the pursuit of the American dream. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gurin, P., Hatchett, S., & Jackson, J. S. (1989). Hope and independence: Blacks’ response to electoral and party politics. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Gurin, P., Miller, A. H., & Gurin, G. (1980). Stratum identification, and consciousness. Social Psychology Quarterly, 43(1), 30–47.

Harris, D. R., & Simms, J. J. (2002). Who is multiracial? Assessing the complexity of lived race. American Sociological Review, 67, 614–627.

Herman, M. (2004). Forced to choose: Some determinants of racial identification in multiracial adolescents. Child Development, 75(3), 730–748.