Abstract

Purpose

High comorbidity has been reported among persons with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), but the occurrence of subjective health complaints (SHCs) in these patient groups is poorly understood. The study aimed to describe the prevalence of SHCs among individuals with psoriasis and PsA in Norway, and investigate whether the severity of their skin condition and their illness perceptions were associated with the number and severity of health complaints.

Method

Participants were recruited through the Psoriasis and Eczema Association of Norway (PEF) (n = 942). The participants answered a self-administered questionnaire covering subjective health complaints, the severity of their skin condition, and their illness perceptions measured with the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ-R).

Results

The prevalence and severity of SHCs were high. Participants with PsA reported more complaints and higher severity of complaints compared with participants with psoriasis. In both groups, the severity of the skin condition was associated with the number and severity of SHCs. Cognitive illness perceptions (consequences) and emotional illness perceptions (emotional affect) were associated with SHCs in participants with psoriasis, whereas only cognitive illness perceptions (consequences and identity) were associated with SHCs in participants with PsA.

Conclusion

The high prevalence and severity of SHCs among individuals with psoriasis and PsA were associated with the severity of the skin condition and illness perceptions. Somatic and cognitive sensitizations are proposed as possible mechanisms. The findings suggest that holistic approaches are essential when managing these patient groups in health care institutions and clinical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease [1]. Norway has the highest prevalence of psoriasis (8.5%) compared with other countries [2]. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic inflammatory arthritis disease associated with psoriasis, and has a prevalence in the range of 0.1–0.2% [3]. Both psoriasis and PsA are associated with a high risk of cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, and gastrointestinal disorders [4–6]. Living with psoriasis and PsA has psychosocial consequences, and depression and anxiety are frequent comorbid conditions [5, 7, 8].

A diagnosis of a chronic disease, such as psoriasis or PsA, requires a person to make adjustments in both the physical and psychological aspects of their life [9]. People’s cognitive beliefs about their illness, often referred to as illness perceptions, are important determinants and predictors of different outcomes. Negative illness perceptions have been reported as associated with poorer functioning and well-being, depression, and more physical symptoms [10–13]. Hence, people’s illness beliefs play an important role in influencing their responses to chronic diseases.

Subjective health complaints (SHCs), such as musculoskeletal pain, gastrointestinal complaints, fatigue, and mood changes, are frequent in the Norwegian population [14–16]. There are no obvious limits distinguishing “normal” endurable health complaints from complaints requiring professional help [14]. SHCs are among the most common reasons for the use of health services, sickness absence, and disability [17]. People with chronic diseases report more subjective health complaints and a higher severity of such complaints compared with the general population [18–23].

Although it is well-documented that psoriasis and PsA are associated with high comorbidity [4–8], there is scarce knowledge of SHCs among individuals with these diseases. Living with a chronic disease can be demanding and patients in the two aforementioned patient groups have reported an impaired quality of life [24, 25]. The fact that SHC can place an additional burden on such individuals, potentially impairing their quality of life even further, together with the fact that other chronically ill individuals have reported high numbers of complaints [18–23], demonstrates the importance of elucidating to what extent people with psoriasis and PsA experience SHCs. Furthermore, investigating associations between SHCs and specific disease characteristics, such as skin symptoms and illness perceptions, could be important to ensure tailored interventions for individuals with psoriasis and PsA.

The study aimed to describe the prevalence of SHCs among individuals with psoriasis and PsA in Norway, and to investigate whether the severity of their skin condition and their illness perceptions were associated with the number and severity of health complaints.

Methods

Study Design and Recruitment Procedure

We conducted a cross-sectional study. A self-administered questionnaire was distributed to 5255 members of the Psoriasis and Eczema Association of Norway, as an attachment to the membership magazine no. 3/2013, during autumn 2013. The criteria for inclusion were in the age 18–70 years and having either psoriasis or PsA. Data collection ended in January 2014.

Questionnaire and Standardized Measurement Tools

The questionnaire included questions covering demographic information, subjective health complaints, severity of the skin condition, and illness perceptions.

Dependent Variables

Subjective health complaints were measured by the Subjective Health Complaints Inventory, in which 29 common health complaints are graded on a four-point scale (0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = some, 3 = severe) as experienced last month [26]. The complaints are divided into five factors [26, 27]: musculoskeletal complaints (headache, migraine, neck pain, shoulder pain, pain in arms, pain in upper back, low back pain, and leg pain) (Cronbach’s α = 0.74), psychological or pseudoneurological complaints (extra heartbeats, heat flushes, sleep problems, tiredness, dizziness, anxiety, and depression) (α = 0.73), gastrointestinal complaints (heartburn, stomach discomfort, ulcer/non-ulcer dyspepsia, stomach pain, gas discomfort, diarrhoea, and constipation) (α = 0.62), allergic complaints (asthma, breathing difficulties, eczema, allergies, and chest pain) (α = 0.58), and flu (cold, flu, and coughs) (α = 0.67). The prevalence of single complaints and complaints divided into subscales, a sum score of the severity of all complaints and of the subscales, and a score for the number of complaints (0–29) are all reported [16, 27].

Independent Variables

Two questions eliciting participants’ self-reported severity of their skin condition were obtained from a psoriasis-specific questionnaire that has been used in the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study [28]. We measured the severity of the skin condition as having a current rash when participating in this study (yes/no) and as the number of places formerly affected with a rash (on a scale of 0–10). From a list of 10 selected body parts, the participants were asked to tick the places where they had ever been affected. We calculated the mean number of places with a rash.

We used the revised version of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (BIPQ-R) to measure illness perceptions [29]. The measurement tool contains nine items: eight items are rated using a 0–10 response scale and one item has an open-ended response. Only the results from the response scale items were used. Five items measure cognitive illness representations: consequences (degree of impact on life), timeline (perceived timeline of illness), personal control (perceived control of illness), treatment control (perceived benefit from treatment), and identity (grade of symptoms associated with the illness). Two items assess emotional illness representations: concern (grade of concern regarding the illness) and emotional affect (grade of affect). The last item assesses comprehensibility/coherence of illness [13, 29]. The mean scores for each item on the response scales were calculated [13].

Statistical Analyses

SPSS Statistics version 23 was used for all analyses, and p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

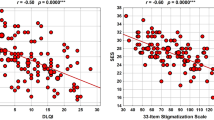

The prevalence of single complaints and complaints on the subscales were computed separately for participants with psoriasis and PsA. If there were less than 50% missing values within the subscales for SHCs, the mean values were calculated; otherwise, the scale was regarded as missing [26]. Differences among participants with psoriasis and PsA in categorical variables were examined using the chi-square test for independence. Yates’ correction for continuity was used for 2 × 2 contingency tables. Differences in means were examined using independent samples t tests. To investigate associations between SHCs, severity of the skin condition, and illness perceptions, we used multiple linear regression models. Dependent variables were the total number of SHCs and severity of complaints. A rash during study participation (dichotomous) and number of places with a rash (continuous), both of which represented the severity of the skin condition, were included as independent variables. To determine which of the individual BIPQ-R items representing illness perceptions should be included as independent variables, bivariate correlation analyses with Pearson correlation were performed for all items against each dependent variable. Only items that significantly correlated with the number and severity of SHCs were included in the regression models, resulting in following seven BIPQ-R items as independent variables: consequences, personal control, treatment control, identity, concern, emotional affect, and comprehensibility/coherence (all continuous). Multicollinearity tests were conducted to test intercorrelations among independent variables. Model fit was evaluated by R 2. Regression analyses were conducted separately for each dependent variable and for participants with psoriasis and participants with PsA, resulting in four regression models. We adjusted for age, gender, and education in the first step (Block 1), and then added all independent variables (Block 2).

Ethics

The project was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REC) in Norway.

Results

Of the 5255 questionnaires sent to the members of the Psoriasis and Eczema Association of Norway, we received 1135 completed questionnaires, corresponding to a response rate of 21.6%. We excluded 193 persons: 166 who did not fulfil the criteria for age and 27 who did not have psoriasis or PsA. Thus, 942 participants were included in the study, of which 573 (60.8%) had psoriasis and 369 (39.2%) had PsA (Table 1). Participants with PsA were older and fewer reported having a current rash compared with participants with psoriasis (Table 1).

Participants with PsA perceived their illness more negatively compared with participants with psoriasis. The results showed significantly higher scores on the following subscales: consequences, timeline, identity, concern, and emotions (Table 1). However, participants with PsA reported significantly better comprehensibility/coherence of their illness compared with participants with psoriasis (Table 1).

The prevalence of SHCs in participants with psoriasis and PsA is shown in Fig. 1. The most prevalent single complaints reported by participants with psoriasis were tiredness, low back pain, arm pain, shoulder pain, and neck pain, while for PsA, they were tiredness, arm pain, low back pain, pain in feet, and shoulder pain (Fig. 1). Participants with PsA reported a significantly higher prevalence of 16 out of 29 complaints compared with participants with psoriasis. Participants with PsA also showed a significantly higher prevalence of musculoskeletal and pseudoneurological complaints (Table 2).

Among all participants, the mean total severity of complaints was 16.86 (Table 2). Participants with PsA reported significantly a higher mean total severity compared with participants with psoriasis. They also reported a higher severity on all subscales, with significant differences for musculoskeletal, pseudoneurological, and gastrointestinal complaints (Table 2). Out of 29 complaints, participants with psoriasis reported the fewest complaints, whereas participants with PsA reported significantly more complaints (Table 2).

The results of the multiple linear regression analyses showed that the severity of the skin condition was a factor for reporting SHCs. Having a rash during study participation was associated with a number of health complaints among participants with psoriasis only. However, increased numbers of places with a rash were significantly associated with the number and severity of complaints in both groups (Table 3). Items representing cognitive and emotional illness representations were associated with SHCs in participants with psoriasis. A higher perceived illness impact (consequences) was associated with the number and severity of complaints, and a higher perceived emotional affect was associated with the number of complaints. Only items representing cognitive illness representations were associated with SHCs in participants with PsA. In this group, a higher perceived illness impact (consequences) and a higher grade of symptoms perceived as belonging to the PsA (identity) were associated with both the number and severity of complaints (Table 3). The models explained 27.5% of the variance (R 2) in the number of SHCs in persons with psoriasis, and 29.0% in PsA. For severity, the model explained 25.4 and 34.1% of the variance in persons with psoriasis and PsA, respectively.

Discussion

We found a high prevalence of SHCs among individuals with psoriasis and PsA. Participants with PsA reported more health complaints and a higher severity of complaints compared with participants with psoriasis. The number of places with rash was significantly associated with the number and severity of health complaints in both groups. Cognitive illness perceptions (consequences) and emotional illness perceptions (emotional affect) were associated with SHCs in participants with psoriasis, whereas only cognitive illness perceptions (consequences and identity) were associated with SHCs in participants with PsA.

With the exception of flu-like complaints, the prevalence and severity of SHCs were higher among persons with psoriasis and PsA compared with what has been previously reported for the general population [14–16, 30]. Studies of the Norwegian general population have reported prevalences in the range of 75–80% for the musculoskeletal subscale and 59–65% for the pseudoneurological subscale [14–16]. By comparison, 91% of the participants in our study reported complaints for the musculoskeletal subscale and 86% for the pseudoneurological subscale, respectively. Several studies have shown that people with other chronic diseases, such as sciatica, low back pain, whiplash associated disorder, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and irritable bowel syndrome, have a higher prevalence of health complaints compared with the general population [18–23]. Parallel to our findings, a tendency for a higher severity of complaints among other chronically ill individuals has also been reported [19]. Psoriasis and PsA are associated with high comorbidity of other diagnoses, such as depression, anxiety, and irritable bowel syndrome [4–8]. Although we had no information on other possible diagnoses, it seems reasonable to assume that such conditions could cause symptoms and complaints that would partially explain our findings.

Somatic and cognitive sensitizations have been proposed as underlying mechanisms to explain why some individuals develop multiple complaints or generalized pain [31, 32]. Somatic sensitization occurs when the nervous system reacts with increased response to stimuli, such as when repeated pain stimuli cause more pain [31]. By contrast, cognitive sensitization occurs through a cognitive bias (e.g., increased focus, attention, and worrying regarding complaints and individual experiences). Such cognitive bias has been reported for several patient groups, including those with psoriasis [33, 34].

We found that the number and severity of SHCs were associated with an increasing numbers of places with a rash in both groups. This could indicate that somatic sensitization is at least partially involved as a mechanism that explains high levels of SHCs. Both psoriasis and PsA involve stimuli such as itching, pain, and discomfort from the skin and joints [1, 3, 35]. Constant, repetitive stimuli, such as rashes, possibly induce somatic sensitization through increased responses in the limbic structures, leading to more complaints and a higher severity of the complaints in individuals with psoriasis and PsA [31, 32]. The associations found between SHCs and higher perceived illness impacts (consequences) and emotional affect may be related to an ongoing continuous cognitive sensitization among these individuals. Both higher perceived consequences and emotional affect could reflect an increased disease impact of complaints already experienced due to having a chronic disease. How already existing complaints are perceived may change and cause reinforcement [36, 37], resulting in a high prevalence and severity of SHCs among individuals with psoriasis and PsA.

As expected, participants with PsA reported a higher prevalence and severity of musculoskeletal complaints. However, they also reported a significantly higher severity of pseudoneurological and gastrointestinal complaints compared with participants with psoriasis. There could be several possible explanations for this finding. First, potential differences in comorbidity between the patient groups could explain the high numbers of SHCs in participants with PsA. However, measures of comorbidity in a lacking point in this study, and it was not possible to reveal any such differences. Second, PsA involves both skin and joint symptoms [3]. It is likely that individuals with PsA experience more constant, repetitive stimuli, such as rashes and pain, than persons with psoriasis, and are thus more prone to experiencing somatic sensitization. However, one weakness of the study was that we did not measure joint symptoms. Third, and finally, participants with PsA perceived their illness more negatively on several items. Hence, cognitive sensitization may cause a greater reinforcement and significantly more complaints in this group.

There were some interesting differences in illness perceptions between the patient groups. Participants with PsA perceived significantly more symptoms (identity), serious impact (consequences), and chronic timeline (timeline) of the illness. These three illness beliefs are associated with more use of health care among primary care patients [38]. Whether such beliefs are critical for predicting the use of health care in PsA, and contribute to differences in health care use between the patient groups, should be explored further. Interestingly, we found that individuals with PsA reported better coherence of their illness, even though they perceived their illness more negatively compared with participants with psoriasis. Longer duration of the chronic disease is associated with better coherence of illness in psoriasis [39]. Since the majority of patients with PsA have been diagnosed with psoriasis almost 15 years prior to their PsA diagnosis [40], we suggest that the difference in perceived coherence of illness could be related to the duration of the disease. In our study, individuals with PsA might have lived longer with their disease compared with individuals with psoriasis, which may also reflect why those with PsA were significantly older.

The study had several limitations. A major weakness was the low response rate. Participation in surveys and epidemiological studies has decreased, and achieving high response rates is an increasing problem [41], which may explain our low response rate. Furthermore, the calculation of the response rate was based on the number of questionnaires sent out to all registered members of the Psoriasis and Eczema Association of Norway. There were weaknesses in this procedure. The membership registry had not been updated and included members not eligible for the participation in the study. Additionally, some questionnaires went to e.g., health care centres rather than to individual members, and therefore, we were not able to ascertain the exact number of members with psoriasis or PsA. We assume that the response rate would have been higher if calculations had been carried out with eligible members only. Since we had no information on which members of the association that was reached, we had no information on the non-responders. It is likely that the members who participated in the study were slightly different from the general population of members with psoriasis and PsA, and therefore, we cannot rule out selection bias. The estimated prevalence values might not represent the general psoriasis and PsA populations in Norway. An overrepresentation of healthy subjects in health surveys has been reported [42], but it is also likely that the most affected members were more motivated to return their questionnaire. Both scenarios could have led to a biased sample. However, the problem of selection bias is less severe for the association studies, as long as the groups are comparable [43]. The number of participants was relatively high, and the length of the confidence intervals for the effect measures were relatively small, thus, strengthening the associations found between groups and variables. Finally, our cross-sectional design did not allow for the determination of the nature of the direction of associations between SHCs, the severity of the skin condition, and illness perceptions, which limits the interpretation of our findings. Contrary to our presumption, the direction of associations could be reverse; for example, experiencing more health complaints could lead to more negative illness perceptions.

Conclusions

In addition to coping with a chronic disease, individuals living with psoriasis and PsA have to manage high levels of SHCs. The observed prevalence and severity of complaints was apparently associated with the severity of the skin condition and negative illness perceptions, and hence, might have been due to somatic and cognitive sensitization. Our findings suggest that holistic approaches in health care, taking into account both the somatic and psychological aspects of having a chronic disease, are essential when managing these patient groups. This in turn has several implications for clinical practice. Carefully examining patients’ experienced SHCs is important in order to rule out manifestations of pathology, as the risk of comorbidity is high in psoriasis and PsA. After excluding pathological explanations, tailored medical treatment to reduce skin symptoms, complemented with psychosocial interventions to achieve less negative illness perceptions, could be important to avoid subjective health complaints.

References

Griffiths CE, Barker JN. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet. 2007;370(9583):263–71.

Parisi R, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–85.

Liu JT, et al. Psoriatic arthritis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. World J Orthop. 2014;5(4):537–43.

Kimball AB, et al. Demography, baseline disease characteristics and treatment history of patients with psoriasis enrolled in a multicentre, prospective, disease-based registry (PSOLAR). Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(1):137–47.

Ni C, Chiu MW. Psoriasis and comorbidities: links and risks. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:119–32.

Gulati AM, et al. On the HUNT for cardiovascular risk factors and disease in patients with psoriatic arthritis: population-based data from the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;75:819–24.

Freire M, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with psoriatic arthritis attending rheumatology clinics. Reumatol Clin. 2011;7(1):20–6.

Parna E, Aluoja A, Kingo K. Quality of life and emotional state in chronic skin disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(3):312–6.

Petrie KJ, Jago LA, Devcich DA. The role of illness perceptions in patients with medical conditions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(2):163–7.

Scharloo M, et al. Illness perceptions, coping and functioning in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and psoriasis. J Psychosom Res. 1997;44(5):573–85.

Murphy H, et al. Depression, illness perception and coping in rheumatoid arthritis. J Psychosom Res. 1999;46(2):155–64.

Treharne GJ, et al. Well-being in rheumatoid arthritis: the effects of disease duration and psychosocial factors. J Health Psychol. 2005;10(3):457–74.

Broadbent E, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire. Psychol Health. 2015;30(11):1361–85.

Ihlebaek C, Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Prevalence of subjective health complaints (SHC) in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2002;30(1):20–9.

Ihlebaek C, Brage S, Eriksen HR. Health complaints and sickness absence in Norway, 1996–2003. Occup Med (Lond). 2007;57(1):43–9.

Indregard AM, Ihlebaek CM, Eriksen HR. Modern health worries, subjective health complaints, health care utilization, and sick leave in the Norwegian working population. Int J Behav Med. 2013;20(3):371–7.

Eriksen HR, Ihlebaek C. Subjective health complaints. Scand J Psychol. 2002;43(2):101–3.

Vandvik PO, et al. Comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: a striking feature with clinical implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(10):1195–203.

Hagen EM, et al. Comorbid subjective health complaints in low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(13):1491–5.

Ihlebæk C, et al. Subjective health complaints in patients with chronic Whiplash Associated Disorders (WAD). Relationships with physical, psychological, and collision associated factors. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2006;16(2):119–26.

Morken MH, et al. Subjective health complaints and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome following Giardia lamblia infection: a case control study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(3):308–13.

Maeland S, Assmus J, Berglund B. Subjective health complaints in individuals with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a questionnaire study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(6):720–4.

Grovle L, et al. Comorbid subjective health complaints in patients with sciatica: a prospective study including comparison with the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70(6):548–56.

Lundberg L, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis measured with SF-36, DLQI and a subjective measure of disease activity. Acta Derm Venereol. 2000;80(6):430–4.

Wahl A, et al. The burden of psoriasis: a study concerning health-related quality of life among Norwegian adult patients with psoriasis compared with general population norms. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(5 Pt 1):803–8.

Eriksen HR, Ihlebaek C, Ursin H. A scoring system for subjective health complaints (SHC). Scand J Public Health. 1999;27(1):63–72.

Ihlebæk C, Eriksen HR, Ursin H. SHC-et måleinstrument for subjektive helseplager. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening. 2004;41:385–7.

Krokstad S, et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):968–77.

Broadbent E, et al. The brief illness perception questionnaire. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(6):631–7.

Ree E, et al. Subjective health complaints and self-rated health: are expectancies more important than socioeconomic status and workload? Int J Behav Med. 2014;21(3):411–20.

Ursin H. Sensitization, somatization, and subjective health complaints. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(2):105–16.

Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Subjective health complaints, sensitization, and sustained cognitive activation (stress). J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(4):445–8.

Fortune DG, et al. Attentional bias for psoriasis-specific and psychosocial threat in patients with psoriasis. J Behav Med. 2003;26(3):211–24.

Verkuil B, Brosschot JF, Thayer JF. A sensitive body or a sensitive mind? Associations among somatic sensitization, cognitive sensitization, health worry, and subjective health complaints. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(6):673–81.

Ljosaa TM, et al. Skin pain and discomfort in psoriasis: an exploratory study of symptom prevalence and characteristics. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(1):39–45.

Brosschot JF. Cognitive-emotional sensitization and somatic health complaints. Scand J Psychol. 2002;43(2):113–21.

Brosschot JF, Gerin W, Thayer JF. The perseverative cognition hypothesis: a review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(2):113–24.

Frostholm L, et al. The patients’ illness perceptions and the use of primary health care. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):997–1005.

Wahl AK, et al. Clinical characteristics associated with illness perception in psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94(3):271–5.

Armstrong AW, Schupp C, Bebo B. Psoriasis comorbidities: results from the National Psoriasis Foundation surveys 2003 to 2011. Dermatology. 2012;225(2):121–6.

Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(9):643–53.

Volken T. Second-stage non-response in the Swiss health survey: determinants and bias in outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:167.

Rothman KJ. Epidemiology. An introduction. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Psoriasis and Eczema Association of Norway (Psoriasis- og eksemforbundet, PEF) and to all those who participated in the study. The project, on which this article in based, has been made possible by funding from the Norwegian ExtraFoundation for Health and Rehabilitation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

The study was funded by the Norwegian ExtraFoundation for Health and Rehabilitation (Project Number DFC6NS).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nordbø, E.C.A., Aamodt, G. & Ihlebæk, C.M. Subjective Health Complaints in Individuals with Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: Associations with the Severity of the Skin Condition and Illness Perceptions – A Cross-Sectional Study. Int.J. Behav. Med. 24, 438–446 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9637-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-017-9637-4