Abstract

Background

China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS), a healthcare financing system for rural residents in China, underwent significant enhancement since 2008. Studies based on pre-2008 NRCMS data showed an increase in inpatient care utilization after NRCMS coverage. However evidence was mixed for the relationship between outpatient care use and NRCMS coverage.

Purpose

We assessed whether enrollment in the enhanced NRCMS was associated with less delaying or foregoing medical care, as a reduction in foregoing needed care signals about removing liquidity constraint among the enrollees.

Method

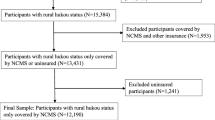

Using a national sample of rural residents (N = 12,740) from the 2011–2012 wave of China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, we examined the association between NRCMS coverage and the likelihood of delaying or foregoing medical care (outpatient and inpatient) by survey-weighted regression models controlling for demographics, education, geographic regions, household expenditures, pre-existing chronic diseases, and access to local healthcare facilities. Zero-inflated negative binomial model was used to estimate the association between NRCMS coverage and number of medical visits.

Results

NRCMS coverage was significantly associated with lower odds of delaying or foregoing inpatient care (OR: 0.42, 95 % CI: 0.22–0.81). A negative but insignificant association was found between NRCMS coverage and delaying/foregoing outpatient care when ill. Among those who needed health care, the expected number of outpatient visits for NRCMS enrollees was 1.35 (95 % CI: 1.03–1.77) times of those uninsured, and the expected number of inpatient visits for NRCMS enrollees was 1.83 (95 % CI: 1.16–2.88) times of those uninsured.

Conclusion

This study shows that the enhanced NRCMS coverage was associated with less delaying or foregoing inpatient care deemed as necessary by health professionals, which is likely to result from improved financial reimbursement of the NRCMS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS), the largest health plan in the world by the number of beneficiaries, currently covers approximately 832 million people in China’s rural area (approximately 80 % of the total rural population) [1]. This program has been considered as the main strategy for financing rural health care by the central government of China and has played a critical role in improving the health of rural residents in China [2]. The NRCMS is funded by subsidiaries from central and local governments and individual beneficiaries’ premium and is organized at county-level [1, 3].Footnote 1 During the early implementation of NRCMS, the main focus of NRCMS was to reimburse inpatient treatment that would result in devastating financial consequences among economically deprived rural households. However, patients seeking preventive care and outpatient services were required to pay a higher rate of coinsurance [1].

Since 2008, NRCMS has experienced a substantial enhancement, as part of Beijing’s economic stimulus package to encourage domestic consumption among rural residents [4, 5]. One popular formula of the NRCMS premium payment in 2008 was for the central and local government to each pay a subsidy of 40 Renminbi (RMB, Chinese currency) per beneficiary per year, while the individuals needed to pay for 20 RMB, meaning that for each NRCMS enrollee a total sum of 100 RMB was contributed to the fund [3]. In 2012, the subsidy from the government had increased to 240 RMB per beneficiary, and the individual’s annual payment rose to 60 RMB. In general, the individual annual payment counted less than 1 % of the average annual income for Chinese rural residents [6]. However, the actual financial burden may vary by region given the relatively high geographic disparity in China [7]. Thus, the total amount of contribution to the fund per beneficiary tripled to 300 RMB from the 2008 funding level [8]. The total annual budget of NRCMS increased from 78.5 billion yuan (96.27 RMB per capita) in 2008 to 204.8 billion yuan (246 RMB per capita in 2011) [1, 9]. In addition, the goal for outpatient reimbursement was set to raise outpatient pooling fund per capita above 50 RMB [10]. As a result, more funding has been provided to cover outpatient services.

Since most of NRCMS beneficiaries had little experience with health insurance prior to their NRCMS enrollment, whether the increased coverage could benefit those previously uninsured people depends upon whether NRCMS could change their behaviors such as skipping or delaying medical care. Our earlier study [11], which used a 2008 pilot dataset from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) [12], showed that among those who reported a need to visit a health care provider during the previous month, those covered by NRCMS were more likely to underutilize outpatient care than the uninsured (odds ratio = 5.61, 95 % confidence interval: 2.04–15.47). Moreover, similar phenomena were noted in an earlier study which found the pre-2008 NRCMS coverage did not reduce medical impoverishment from the expensive outpatient services for chronic conditions [13]. The reason why NRCMS beneficiaries did not seek care when needed in 2008 may be due to liquidity constraint [14] (i.e., some NRCMS beneficiaries may still not afford outpatient care due to the limited NRCMS coverage of outpatient care before 2008) or “status quo bias” of newly insured people [15] (i.e., sticking to their old habits of delaying care even after NRCMS coverage).

Given that NRCMS has offered more coverage for outpatient and inpatient care since 2008 and most of the beneficiaries have stayed in that program for several years, both the liquidity constraint and the status quo bias might have attenuated over time. However, there was a lack of evidence on whether NRCMS beneficiaries would be more likely to seek care after the more generous coverage. Some studies have shown that insurance programs’ liquidity effect on health care utilization could be weakened by health care cost inflation [16, 17]. For instance, a doubling of NRCMS fund is unlikely to afford twice as much service since the cost has more than doubled.

Previous studies have shown that within the NRCMS, insurance coverage was positively associated with the high caesarean section rate and more use of prescription drugs [18, 19], which suggested consumers were sensitive to medical prices, and they used more health care when they were insured. Yet, it is unclear how much of such increase is due to liquidity effect whereby beneficiaries are more likely to use needed care because of the relaxed budget constraint. Caesarean sections, for instance, is often an elective procedure in China [20] and therefore it is likely that an increase in caesarean section among NRCMS-covered women could come from moral hazard rather than clinical indication.

To our knowledge, only a limited amount of research has been done to examine the impact of the enhanced NRCMS on its beneficiaries’ behavior of foregoing health care. The hypothesis of this study was that the enhanced NRCMS in 2011–2012 would be associated with a lower likelihood of foregoing health care as compared with those uninsured. Unlike an increase in health care utilization which could come from both liquidity effect and moral hazard, a decrease in foregoing needed care could be more of a result from liquidity effect rather than moral hazard. Therefore, if NRCMS enrollment is associated with less foregone care, we may have more confidence that NRCMS increases health care utilization by reducing liquidity constraint among its enrollees.

Methods

Study Sample and Variables

We drew our data source (N = 12,740) from the 2011–2012 wave of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationwide survey program conducted among Chinese adults aged 45 and older that examined their retirement status, health, and related social-economic issues through a face-to-face household interview in 28 provinces of China. The sampling framework of CHARLS was described in great detail elsewhere [21]. CHARLS 2011–2012 is the first nationwide survey that represents the Chinese population ages 45 and older, funded through a joint project by the National Institute on Aging of the United States, the World Bank, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China. Modeled after the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) in the USA and other related aging surveys in the European countries, CHARLS collected information on the participants’ demographic characteristics, family structure, health status, health care and insurance, crucial biomarkers as well as information about their communities.

Our sample included the mainland China’s rural residents who were eligible for NRCMS only, i.e., those with a registered rural residence and did not have health care coverage from urban health plans. The key construct of the respondent’s insurance enrollment was a dummy variable for whether enrolled in the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme. People who remained uninsured at the time of the survey were coded as the reference category.

To estimate the association between the enhanced NRCMS and care utilization, we chose four outcome variables to operationalize the construct of health care utilization: (1) whether one skipped or delayed outpatient care when ill, excluding those who reported were already under treatment; (2) whether one did not seek inpatient care when recommended by a physician; (3) number of outpatient visits during the previous month; and (4) number of inpatient visits during the last 12 months. The model of delaying/foregoing outpatient care when ill was run on the subsample of respondents who reported an event of illness during the previous month (N = 2,905). And the model of foregoing inpatient care was run on the subsample of respondents who reported an instance whereby he/she was recommended by a physician for hospitalization (N = 1,518). The other two models of number of health care visits were run on the national rural resident sample of 2011–2012 CHARLS (N = 12,740).

We adjusted the following covariates in the analysis: age group, gender, educational attainment (categorized into four groups: elementary school, junior high school, high school or above vs. no formal education), geographic regions (West, Central China vs. East), and household expenditure level per month (defined as a proxy measure for economics status and categorized into four groups, by quartile: 0–$106, $106–$211, $211–$374 vs. $374 and above). Previous studies showed that household expenditure level was a more accurate measure than individual income for economic status and long-term resources for the elderly [20, 22]. We also included the participant’s self-reported chronic diseases, including hypertension, lung disease or asthma, cardiovascular diseases such as heart problems, stroke and dyslipidemia, arthritis, stomach disease, or other chronic diseases including diabetes, cancer, liver disease, kidney disease, and psychiatric problems. To account for the impact of geographic accessibility on health care utilization, we further controlled for whether having a general hospital, a pharmacy, a community health center, or a health clinic in the village/community.

Data Analysis

We estimated the association between NRCMS and delaying/foregoing outpatient care and inpatient care separately, using the survey-weighted logistic regressions of the subpopulations, as described above. As for the two models using the national rural sample, we used zero-inflated negative binomial model (ZINB) to estimate the associations between NRCMS and number of medical visits. The appropriateness to use the ZINB model was tested first. Significant results of the equal dispersion assumption (p < 0.05) and the Vuong test (p < 0.001) suggested that the ZINB model was preferred (p < 0.001).

Results

A total of 12,740 rural residents aged 45 and older in 2011–2012 were included in the analysis. A majority of them had NRCMS coverage, with 6.7 % (N = 854) remained uninsured (Table 1). The distribution of age, gender, educational attainment, household expenditure per month, and geographic regions were not significantly different between the NRCMS beneficiaries and the uninsured, whereas the NRCMS beneficiaries reported more health clinics in their communities than those uninsured. As expected, the uninsured reported having fewer chronic diseases than those NRCMS enrollees. As Table 1 shows, the self-reported rates of hypertension, stomach disease, and other chronic diseases were significantly lower among the uninsured. It indicated a possible adverse selection in the NRCMS enrollment. However, the lower rates of chronic diseases might be due to an under-diagnose issues among the uninsured population [23].

Among rural participants in the CHARLS 2011–2012, 12.7 % of NRCMS beneficiaries skipped or delayed outpatient care even if they reported an illness in the previous month (Table 2), compared to 17.5 % among the uninsured population. The bivariate association between foregoing outpatient care and insurance status after adjusting for sampling weights was not statistically significant (p = 0.608). Twenty-eight percent of NRCMS enrollees didn’t seek inpatient care against medical advice in the past year, which was significantly lower than the uninsured (46.7 %, p = 0.010). Among people who used outpatient care in the previous month, those covered by NRCMS had 2.12 visits on average, compared with 1.98 visits among the uninsured (Table 2). Similarly, among people who used inpatient care during the previous year, NRCMS enrollees had 1.46 hospitalizations whereas the uninsured rural residents averaged 1.41 hospitalizations.

Table 3 shows the association between NRCMS insurance and delaying/foregoing outpatient and inpatient care, adjusting for all covariates. The survey-weighted standard logistic regression estimated that the odds ratio of NRCMS coverage on delaying/foregoing outpatient care when ill was 0.72 (95 % CI: 0.42–1.25), not statistically significant. Meanwhile, the NRCMS enrollees were significantly less likely to delay/forego inpatient care compared to the uninsured. The odds ratio in the regression was 0.42 (95 % CI: 0.22–0.81). In addition, the respondent’s insurance status, low-income, living in the western region of China, self-reported other chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer, liver disease, kidney disease, and psychiatric problems were other predictors of delaying/foregoing outpatient care when ill, while low-income status, having had self-reported other chronic conditions were predictors of not seeking inpatient care when recommended by a physician.

Table 4 presents the association between insurance status and number of health care visits after adjusting for covariates. Among those who used outpatient care (i.e., non-zeros in the ZINB model), the expected number of outpatient visits for NRCMS enrollees was 1.35 (95 % CI: 1.03–1.77) times of those uninsured. Among those who used inpatient care, the expected number of inpatient visits for NRCMS enrollees was 1.83 (95 % CI: 1.16–2.88) times of those uninsured.

Discussion

Our findings from this 2011–2012 national wave of CHARLS data were consistent with previous studies which found that pooling outpatient care fund could encourage the outpatient visits and protect the enrollees from the serious illness [24, 25]. But they were different from those of our previous study using the 2008 CHARLS pilot data, where NRCMS enrollment was found to be a positive predictor of foregoing outpatient care (as compared with people who were uninsured) [11]. As we discussed in the “Introduction” section, in 2008, few provinces offered the coverage of outpatient care expenses on an individual account. Up to 2011, however, more than 85 % of areas developed the pooling of outpatient care fund [26]. It is possible that this trend gradually transformed the NRCMS into a more comprehensive health cooperative system and boosted the outpatient service utilization in this process. However, the benefit package of outpatient reimbursements by NCMS was still limited compared to the reimbursements on inpatient costs, which may explain why disparities between outpatient and inpatient care utilization still existed although the outpatient services had been largely covered after the reform.

The enhanced financing might not be the sole reason why now NCRMS became associated with more use of care when needed: the program’s administrative staff, the health care providers serving the rural areas, and the health information technology professionals could all have learned how to better use this newly introduced cooperative scheme [27]. Meanwhile, it is hard to ignore the possible learning curve among China’s rural residents who had never had health insurance before. These new enrollees might have to learn to facilitate their own health care utilization with the NCRMS coverage. The opposite signs we found from two waves of CHARLS data might very well be a result of the learning process of NRCMS enrollees.

Our study used a national sample representative of the population aged 45 or above in mainland China, a dataset that covers the participants’ health care utilization, health status, and demographic information. Given the cross-sectional nature of this observational dataset, issues such as adverse selection could have occurred to undermine the validity of this study (i.e., sicker patients are more likely to enroll in NRCMS and use more medical care). A recent study of NRCMS showed that those with registered rural residence in “combined household” (one that has both rural and urban members in the household) is more likely than those in the “pure rural household” (where all family members are rural residents) to enroll in NRCMS [28], and it is not impossible that NRCMS enrollees in “combined households” were also more likely to use health care services. In addition, there might be a degree of under-reporting of specific diseases in the uninsured population due to their lack of access to health services. It was likely that among the uninsured, those who were diagnosed may have more severe diseases than those diagnosed in the NRCMS-covered population. Those unobserved and unmeasured variables were not accounted for in the survey-weighted logistic regression, hence the possibility of unobserved selection bias.

The second concern was that the implementation paces of this enhanced NRCMS vary across different regions (China has 283 regions or “diqu”s, the administrative unit between province and county). The sample size within each region was not sufficient to allow for a multilevel analysis. This could be a potential problem if region-level socioeconomic factors influence both the participants’ likelihood of insurance enrollment and of medical care utilization. However, this bias could be limited because the national and provincial government contributed most of the funding for the NRCMS program [1].

One of the aims behind the enhancement of NRCMS was to enable the relatively vulnerable rural population to pay for the basic medical services and maintain financial security when facing liquidity constraint, protecting them from the heavy economic burden associated with acute and chronic illnesses. As insurance coverage has been shown to increase both outpatient and inpatient utilization [29], it is reasonable to expect that with the improvement of insurance coverage among NRCMS enrollees, they will be more likely to utilize the medical care when necessary than those uninsured people.

It is encouraging to find that the enhanced NRCMS coverage in 2011–2012 was associated with increased use of needed medical care, which is more likely to result from improved liquidity effect than from the moral hazard mechanism whereby new enrollees could start unnecessary care utilization. Despite these encouraging signs after NRCMS enhancement as shown in our study, geographic disparities and socioeconomic disparity may still persist, as also shown in our significant results of the region and income dummies regressed on foregone care outcomes. The most alarming message from our study, however, is that people with certain chronic diseases (diabetes, cancer, liver disease, kidney disease, and psychiatric problems) did not seek inpatient care even when it was recommended by health care professionals. Those people were particularly vulnerable to the risks associated with skipping care, and skipping care for conditions such as diabetes and kidney disease might very well increase rather than decrease the total health care expenditure in the long run. More sophisticated and comprehensive payment plans for these chronic diseases, as well as stronger patient education programs, might thus be needed to deal with this challenge in rural China.

Our findings do not serve a rejection to the moral hazard hypothesis in China’s health insurance plans. Both evidence and theory show the serious issue of moral hazard among China’s urban employer-sponsored health plan [30], and NRCMS might be no exception. To deal with practical challenges and potential moral hazard from the supply side, the NRCMS programs in mainland China have been exploring many types of funding and payment experiments, including expanding the risk pool from the county level up to the region (diqu) level, developing “major disease protection mechanism,” introducing payment reform such as diagnosis related groups, per-diem payment, outpatient prepaying [31–34], and so on. These explorations were aimed at enhancing the utilization of health services and controlling the health care expenditures. Under this context, future studies are needed to explore which of these specific implementation plans have the best potential to help the disadvantaged groups as we identified in this study and which mechanism could be best at minimizing moral hazard both from the supply side and the demand side.

Notes

Appendix I provides a brief chronology for the step-by-step enhancement of the NRCMS program from 2008 to 2012.

References

MOH. Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. New Cooperative Medical Scheme in 2011. 2012;1–6. http://www.moh.gov.cn/mohbgt/s3582/201202/54208.shtml. Accessed May 2015.

Xu K, Saksena P, Fu XZH, Lei H, Chen N, Carrin G. Health care financing in rural China: new rural cooperative medical scheme. Geneva: World Health Organization Publ.; 2009. http://www.who.int/health_financing/documents/cov-pb_e_09_03-china_nrcms/en/.

Mao Z. The development status and challenges of New Cooperative Medical Scheme. 新型农村合作医疗的发展状况与挑战. Health Econ Study. 2009;261:10–1.

Ying M, Du Z. The effects of medical insurance on durables consumption in rural China. China Agric Econ Rev. 2012;4:176–87. doi:10.1108/17561371211224764.

Zheng Z. The influence of new rural cooperative medical scheme on domestic consumption in Rural China—an empirical analysis. 新型农村合作医疗保险与拉动农村内需——一个来自于中国农村微观数据的实证分析. CCISSR Conference Paper. 2010.

Chinanews. Annual income for Chinese farmers in 2012. 2013. http://www.chinanews.com/cj/2013/01-18/4499857.shtml. Accessed 5 Apr 2016.

Xie Y, Zhou X. Income inequality in today’s China. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(19):6928–33.

Ying Y. Differential funding: a necessary requirement of the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme’s development差别化筹资: 新农合制度发展的必然要求. China Health. 2012;4:36–7.

Wu L, Shen S. An evaluation of New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme我国新型农村合作医疗制度运行状况评估. J Southwest Univ (Social Sciences Edition). 2011. http://xbbjb.swu.edu.cn/viscms/u/cms/xbbjb/201310/23092904k8zf/2011-2-096.pdf. Accessed June 2015.

MOH. Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. New rural cooperative medical scheme development report (2002–2012). 2013. http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jws/s3582g/201309/dc9ea566f6b9427eadcf1028f470317c.shtml. Accessed May 2015.

Shi L, Zhang D. China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme and underutilization of medical care among adults over 45: evidence from CHARLS pilot data. J Rural Health. 2013;29:s51–61.

Smith Jea. Health outcomes and socio-economic status among the elderly in China: Q2 evidence from the CHARLS Pilot. Working Paper. 2010.

Yip W, Hsiao W. Non-evidence-based policy: how effective is China’s new cooperative medical scheme in reducing medical impoverishment? Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1–33.

Nyman JA. The value of health insurance: the access motive. J Health Econ. 1999;18(2):141–52.

Decker S, Doshi J, Knaup A, Polsky D. Health service use among the previously uninsured: is subsidized health insurance enough? Health Econ. 2012;21:1155–68. doi:10.1002/hec.1780.

Lei X, Lin W. The new cooperative medical scheme in rural China: does more coverage mean more service and better health? Health Econ. 2009;18(S2):1–36.

Ma Y, Zhang L, Chen Q. China’s new cooperative medical scheme for rural residents: popularity of broad coverage poses challenges for costs. Health Aff (Project Hope). 2012;31:1058–64. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0808.

Long Q, Klemetti R, Wang Y, Tao F, Yan H, Hemminki E. High Caesarean section rate in rural China: is it related to health insurance (New Co-operative Medical Scheme)? Soc Sci Med (1982). 2012;75:733–7. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.054.

Sun X, Jackson S, Carmichael G, Sleigh AC. Prescribing behaviour of village doctors under China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2009;68:1775–9. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.043.

Smith JP, Majmundar M (Eds.). Aging in Asia: Findings from New and Emerging Data Initiatives. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012.

CCER. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS). Peking University; 2011. http://charls.ccer.edu.cn/en. Accessed Dec 2013.

Strauss J, Park A, Smith JP. Health outcomes and socio-economic status among the elderly in Gansu and Zhejiang Provinces, China: evidence from the CHARLS pilot. J Popul Ageing. 2010;1:111–42. doi:10.1007/s12062-011-9033-9.Health.

Feng X, Pang M, Beard J. Health system strengthening and hypertension awareness, treatment and control: data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:29–41. doi:10.2471/BLT.13.124495.

Li H. The SWOT analysis and the countermeasures for overall manning in outpatient clinics in New Rural Cooperative Medical Service. Modem Hosp Manage. 2010;3:28–30.

Li X, Zhang W. The impacts of health insurance on health care utilization among the older people in China. Soc Sci Med. 2013;85:59–65.

Wen J. Report on the Work of the Government 2012. March 5th, 2012 at the fifth Plenary Session of the National Congress. 政府工作报告——2012年3月5日在第十一届全国人民代表大会第五次会议上. 2012.

Meng Q, Xu K. Progress and challenges of the rural cooperative medical scheme in China. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:447–51.

Qin L, Pan S. Adverse selection in China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme. China Agric Econ Rev. 2012;4:69–83.

Buchmueller TC, Grumbach K, Kronick R, Kahn JG. The effect of health insurance on medical care utilization and implications for insurance expansion: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev: MCRR. 2005;62:3–30. doi:10.1177/1077558704271718.

Ying M, Wenbin F, Fengye W. Analysis on the game theory view of the moral hazard in the urban workers’ basic medical insurance [J]. Chin Med Ethics. 2006;4:028.

Babiarz K, Miller G, Yi H, Zhang L, Rozelle S. New evidence on the impact of China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme and its implications for rural primary healthcare: multivariate difference-in-difference. BMJ. 2010;341:c5617.

Barber L, Yao L. Health insurance systems in China: a briefing note. World Health Report. 2010. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/37ChinaB_YFINAL.pdf. Accessed May 2015.

Yip W, Eggleston K. Provider payment reform in China: the case of hospital reimbursement in Hainan province. Health Econ. 2001;339:325–39.

Yip WC-M, Hsiao W, Meng Q, Chen W, Sun X. Realignment of incentives for health-care providers in China. Lancet. 2010;375:1120–30. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60063-3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article is a secondary data analysis. It does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Shi, L., Tian, F. et al. Care Utilization with China’s New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme: Updated Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study 2011–2012. Int.J. Behav. Med. 23, 655–663 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9560-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9560-0