Abstract

Mollusks are a very important component of the invertebrate faunal biodiversity in marine ecosystems. However, knowledge on this (and other groups) is still incomplete. Inventories of fauna are very important tools to learn the biodiversity associated with specific regions and of specific zoological groups. In this paper, I report 103 species of heterobranch mollusks occurring along the Pacific coast of Colombia, including previous peer-reviewed records and new information. Of these, 23 are new records for the Pacific coast of Colombia, and a total of 32 species are registered for the first time in at least one locality along this shore. The most species diverse family is Chromodorididae, followed by Ellobiidae. The most diverse locality is Gorgona Island, closely followed by Malpelo Island. There is still much to learn from this rather isolated region, the northern Pacific coast of the South American continent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Marine mollusks are one of the best-known and most common invertebrate groups in the oceans. Within the mollusks, Gastropoda is the class with the highest species richness, with its approximately 70,000 described species accounting for some 85% of all the species known in this phylum (Brusca et al. 2016). Heterobranchia is one of the most species-rich groups within Gastropoda (Dinapoli and Klussmann-Kolb 2010). It has been shown that high heterobranch richness is correlated with healthy ecosystems and highly diverse communities (Kaligis et al. 2018; Undap et al. 2019). The reduction of heterobranch diversity might indicate climate changes and ecosystem deterioration (Nimbs and Smith 2018). Also, many species of heterobranchs may be potential sources of bioactive products (Fisch et al. 2017; Furfaro et al. 2020).

The Pacific coast of Colombia, one of the megadiverse countries in the world, is part of the Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena bioregion, a well-known biodiversity hotspot (Mittermeier et al. 2004, 2011). Nevertheless, this honorific title is awarded basically due to terrestrial groups, such as plants, insects, birds, amphibians, and reptiles. In the marine realm, however, the Tropical Eastern Pacific (TEP), where the Pacific coast of Colombia is located, is relatively modest in terms of biodiversity (Costello et al. 2010). This is evidenced by, in the case of mollusks, the smaller number of newly discovered species in the TEP compared to other regions, such as the Indo-Pacific, Tropical West Atlantic, and Tropical East Atlantic (Bouchet et al. 2006). This pattern might hold for other taxa as well. Two possible reasons can be hypothesized for this fact: (1) The region has low marine biodiversity as compared to other regions, or 2) the marine biodiversity in the region is still poorly known, due to limited access and to the lack of specialists in marine biodiversity working in this part of the planet. Barber et al. (2014) emphasized that biodiversity research in developing countries faces conditions that might limit the advancement of knowledge in this paramount task. Either way, true low biodiversity or the need for more research, it is clear that many biological groups are still under-studied and that comprehensive inventories are still needed, especially in those countries where biodiversity is both poorly understood and endangered. Furthermore, many species of heterobranchs in the Colombian portion of the TEP tend to be numerically rare and seasonal, as has been shown for other regions in the eastern Pacific (e.g., Hermosillo 2006; Bertsch 2019) and proposed for heterobranchs in general (Schubert and Smith 2020).

The biodiversity of mollusks in certain regions of the Colombian Pacific has been assessed (e.g., Cantera K. et al. 1979; Cosel 1985; Kaiser and Bryce 2001; Lozano-Cortés et al. 2012; López de Mesa and Cantera 2015); however, the non-shelled heterobranchs have been mostly neglected. The most recent and up-to-date list of species to this group, to the best of my knowledge, is the work by Ardila et al. (2007). In their work, these authors reported 32 species of “Opisthobranchia” for the Colombian Pacific coast. In addition, field guides for the Pacific coast of the Americas, including the TEP region (Behrens and Hermosillo 2005; Camacho-Garcia et al. 2005), mention only 9 species of heterobranch sea slugs occurring in Colombia, although many others are distributed only to Panama or have a distributional gap, jumping to Ecuador and the Galápagos Islands. In a survey of the molluscan literature, I found reports of 84 species of “Lower Heterobranchia” and Heterobranchia from the Colombian Pacific region, including 18 species of Nudibranchia. Considering just the nudibranchs in each of the three biogeographical provinces of TEP, 116 species have been reported from the Cortezian province, 117 from the Mexican, and 137 from the Panamic sensu stricto (Bertsch 2010). This raised serious doubts regarding the true number of Heterobranchia species on the Colombian Pacific coast. It seemed reasonable that the true number of species for the Colombian Pacific must be higher than what is currently known. This report presents a more comprehensive species list of these amazing creatures.

Materials and methods

Study area

The Pacific coast of Colombia (Fig. 1) extends for ~ 1545 km from the border with Panama (7.2109° N; 77.8891° W) to the border with Ecuador (1.4333° N; 78.8167° W) (INVEMAR 2020). It reaches far westward into the Pacific Ocean because of Malpelo Island, located more than 470 km off the continental coast from Buenaventura Bay. The climatic and oceanographic conditions on the Colombian Pacific coast and basin vary annually and are affected by the Intertropical Convergence Zone. According to Rangel-Ch. and Arellano-P. (2004), precipitation varies annually between 3007 and 6480 mm, humidity ranges from 81.3 to 89.7% and annual mean air temperature varies between 26.1 and 27.2 °C. On the oceanic conditions, Málikov and Villegas-Bolaños (2005) reported an average sea-surface water temperature of 27.4 °C and an average sea-surface salinity of 28.1. Finally, the tidal range on the Pacific coast of Colombia revolves around 5.0 m (IDEAM 2019).

The Pacific coast of Colombia (South America) with the localities mentioned in this work marked with a star. (Source: https://www.disruptivegeo.com/tag/large-scale-international-boundaries/)

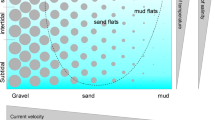

The Pacific coast of Colombia is divided into two physiographically different parts (INVEMAR 2020): a southern part (from the border with Ecuador to Cabo Corrientes) and a northern part (from Cabo Corrientes to the border with Panama). The southern part is bordered mainly by mangrove swamps, muddy flats, and sandy beaches; estuaries are also very common and large in this region. Sedimentary cliffs can be found at Isla del Gallo (in Tumaco) and Buenaventura and Málaga bays. In the northern part, the coast is mainly rocky of tectonic origin, with some pocket beaches and small mangrove forests. Rocky reefs and islets are also common in this region. Besides mangroves, muddy flats, and rocky shores, some coral reef patches and modestly developed fringing coral reefs are present in Gorgona and Malpelo Islands and Utria and Cabo Marzo on the continental shore. This variety of ecosystems provides a wide range of habitats to support a high biological diversity.

Sampling and identification

Since 2006, I have made casual records of heterobranch sea slugs during field practices of marine biology courses and field trips of research projects in five localities in the Pacific coast of Colombia (Fig. 1): Gorgona National Natural Park (Gorgona), Uramba-Bahía-Málaga National Natural Park (Málaga), Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary (Malpelo), San Pedro-Buenaventura Bay (Buenaventura), and few localities in the Chocó Department: Piñas and Cabo Marzo (Chocó). Most records were made in the intertidal (tide pools, under rocks, etc.) or snorkeling in the shallow subtidal regions of these localities. Very few were gathered during scuba dives. All species found were collected and identified alive in the field by visual examination and the use of specialized field guides (Behrens and Hermosillo 2005; Camacho-Garcia et al. 2005) and then returned to the ecosystem from which they were taken. No samples were collected for further examination in the laboratory. A recent permit has allowed some specimens of common species to be collected and stored in the Reference Marine Collection of Universidad del Valle (Biology Department).

These observations were compared with the published information assessed on heterobranch biodiversity along the Pacific coast of Colombia to generate a comprehensive list of heterobranchs. The many recent changes in the phylogeny and taxonomy that have been proposed for this group, based on studies using molecular DNA techniques and more detailed anatomical observations (Dinapoli and Klussmann-Kolb 2010; Carmona et al. 2014a, b; Valdés et al. 2018), have been incorporated into this list. These changes are shown in Table 1. Finally, Figs. 1 and 4–10 were prepared with Photoshop (Adobe Photoshop 2021) and Figs. 2 and 3 with R (R Core Team 2020).

Results

A total of 103 heterobranch species (including some species as sp.), in 40 families, are now recorded for the Pacific coast of Colombia (Table 2). From this list, only 5.8% are within the unresolved clade “Lower Heterobranchia”; the remaining 94.2% belong to Euthyneura. With 10 species, the Chromodorididae had the highest family-level richness (9.7% of all the species), followed by Ellobiidae, Pyramidellidae, and Discodorididae with 9, 8, and 6 species respectively. Of all the families, 19 (47.5%) are represented by only one species, 7 families are represented by two species, and 14 families are represented by 3 or more species (Fig. 2). This work reports 23 new records of heterobranch species, accounting for 22.3% of all the species now known from the Pacific coast of Colombia. The 20 species of Nudipleura account for the majority (87.0%) of these new records. The remaining belong to the clades Euopistobranchia (2 species) and Panpulmonata (1 species).

At the five localities, Gorgona showed the highest species richness, followed by Malpelo and Málaga. Chocó with 18 and Buenaventura with 10 species showed the lowest richness. Forty nine percent of all the species recorded for Gorgona are new records. The ratio of new to total records decreased as follows: Buenaventura 30.0%, Málaga 27.8%, Malpelo 10.4%, and Chocó 5.6% (Fig. 3). From the 23 new records of Heterobranch species for the Colombian Pacific, 13 species were exclusive to Gorgona, 3 species to Málaga, and 2 species to Malpelo. Phidiana lascrucensis and Geitodoris mavis were common to Gorgona, Málaga, and Buenaventura; Marionia cf. kinoi was common to Gorgona and Malpelo; Doris pickensi was common to Malpelo and Málaga; and Anteaeolidiella chromosoma was common to Málaga and Buenaventura (Fig. 4). In addition to the 23 new records, another 9 species were recorded for the first time in at least one of the five localities; hence, 32 new records are reported (i.e., 31.1% of the 103 species).

Since the start of my data collection (ca. 12 years ago), the 23 new species reported for the Pacific coast of Colombia and the 32 new records for at least one locality along this coast render an annual average of new records of heterobranch sea slugs of 1.9 and 2.7 respectively. However, no special effort on heterobranch sea slugs sampling or collecting was implemented. It is important to mention that no quantitative species abundance studies on heterobranchs (such as those by Hermosillo 2006 and Bertsch 2019) have been undertaken on the Pacific coast of Colombia. Based on my experiences, the most common and abundant species are Elysia diomedea, Dolabrifera nicaraguana, and Berthellina ilisima, although there are other common but not abundant species (Figs. 5 and 6a–c).

Species comments

Each new record for the Pacific coast of Colombia (i.e., 23 species) constitutes a range extension or fills a gap in the distribution of a species; hence, it is commented in short below. For pictures of these species, see Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. All pictures were taken by the author except when otherwise stated.

Nudibranchia

Okenia cf. academica Camacho-Garcia & Gosliner, 2004. There are 8 species reported for the TEP (Camacho-García and Gosliner 2004; Behrens and Hermosillo 2005). From these, only O. angelensis is distributed from the Gulf of California to Chile, so it could potentially be present in the Colombian Pacific. The southern limit for the remaining 7 species is Costa Rica, with most occurring in the Gulf of California. Camacho-García and Gosliner (2004) described a new species, namely, O. academica. The specimen reported here is relatively similar to this species: The body is milky translucent with yellow tips on the dorsal appendages and sides of the gills, and the rhinophores are bright white (Fig. 6d). The specimen was recorded from Málaga; this extends the southern range by more than 800 km.

Limacia janssi (Bertsch & Ferreira, 1974). Uribe et al. (2018) report four species for the eastern Pacific. Only one species (L. antofagastensis) is known from the southern hemisphere. The only tropical species is L. jansii (Fig. 6e), known to occur from the southern Gulf of California to Panamá, so the record from Gorgona constitutes the southernmost record for this species and extends it for almost 480 km.

Tambja eliora (Er. Marcus & Ev. Marcus, 1967). Camacho-Garcia et al. (2005) report three species of Tambja, two (T. abdere and T. eliora) distributed from the Gulf of California to Costa Rica and one (T. mullineri) endemic to the Galápagos Islands. This record (Fig. 6f) from Malpelo extends the distribution of this species almost 550 km southward.

Tyrannodoris leonis (Pola et al., 2005). This species was originally described as Roboastra leonis for the Galápagos Islands, but Pola et al. (2005) mention the existence of an illustration of a similar animal from La Paz (Gulf of California). There is also a record from Costa Rica (http://slugsite.us/bow/nudwk517.htm). The specimen (Fig. 7a) recorded at Malpelo confirms its presence in the TEP and fills a gap in its distribution.

Diaulula greeleyi (MacFarland, 1909). This species is known from the Atlantic (Florida, Brazil, and South Carolina) and Pacific (Punta Eugenia, Baja California and Nayarit, Mexico to Panama) coasts of the Americas (Camacho-Garcia et al. 2005). This record (Fig. 7b) from Gorgona is the southernmost on the eastern Pacific for this species, increasing its geographic range by almost 480 km southward.

Geitodoris mavis (Marcus & Marcus, 1967). Camacho-García et al. (2005) report this species from Mexico, Costa Rica, and the Galapagos Islands. The specimens from Gorgona, Málaga, and Buenaventura are lighter in color than the one depicted in the Field guide to the sea slugs of the tropical eastern Pacific; however, the white line on the gill sheath (Fig. 7c) leaves no doubt on the identification. This record fills a gap in the distribution of the species along the TEP.

Doris pickensi Marcus & Marcus, 1967. Behrens and Hermosillo (2005) report 5 Dorid species for the TEP. In a redescription of the species, Camacho-Garcia and Gosliner (2008) confirm the presence of this species from the Gulf of California to Costa Rica. The specimens from Malpelo and Málaga reported here were small (ca. 4 mm) and almost uniform lemon-yellow (Fig. 7d). These records are the southernmost for this species and extend its geographic range to 700–800 km to the southeast of the Pacific ocean.

Chromolaichma dalli (Bergh, 1879). Bertsch (1978) reports this species from Baja California and Costa Rica. It is also known from Panamá and the Galápagos Islands (Behrens and Hermosillo 2005; Camacho-Garcia et al. 2005). This record (Fig. 7e) from Gorgona fills a gap in the distribution range of this species in the TEP.

Mexichromis antonii (Bertsch, 1976). Bertsch (1978) reports this species from Baja California, the Gulf of California, Colima (México), and Costa Rica. Behrens and Hermosillo (2005) and Camacho-Garcia et al. (2005) also include Panamá. This record (Fig. 7f) from Gorgona extends the geographic range by almost 480 km southward.

Mexichromis tura (Marcus & Marcus, 1967). Bertsch (1978) reports this species from La Paz, Nayarit (México) and Panamá. This record (Fig. 8a) from Málaga extends the geographic range of this species by almost 400 km southward.

Doriopsilla janaina Er. Marcus & Ev. Marcus, 1967. This species is known from the Gulf of California down to Panamá and in the Galápagos (Behrens and Hermosillo 2005). Hence, the record (Fig. 8b) from Gorgona fills a gap in its distribution along the TEP.

Dendronotida

Marionia cf. kinoi Angulo-Campillo & Bertsch, 2013. Angulo-Campillo and Bertsch (2013) report only two species of Marionia in the eastern Pacific: M. kinoi and Marionia sp. M. kinoi has been reported throughout the Mexican Pacific, Costa Rica, Panamá, and the Galápagos Islands (Angulo-Campillo and Bertsch 2013). The unnamed species is known only from Isla Isabel (México) (Behrens and Hermosillo 2005). According to Bertsch (pers. comm.), the photographed specimens from Gorgona and Malpelo (Fig. 8c) do not resemble M. kinoi or Marionia sp.; hence, this could be a third species from the TEP, but more studies need to be done.

Arminida

Armina sp. Rafinesque, 1814. In a revision of the genus Armina, Báez et al. (2011) report three species for the eastern Pacific, one unnamed. From these, A. californica is distributed from Alaska to Panamá and Perú, A. cordellensis from central California, and Armina sp. from Baja California. The specimen recorded at Gorgona is unlike any of the preceding species (Fig. 8d). It was very small (ca. 2–3 mm) with a white-yellowish background with longitudinal reddish stripes.

Aeolidida

Bulbaeolidia sulphurea Caballer & Ortea, 2015. Carmona et al. (2017) report this species from the Galápagos Islands and the Pacific coast of Panama, Costa Rica, and El Salvador. This record (Fig. 8e) from Gorgona fills a gap in the distribution of this species along the TEP.

Anteaeolidiella chromosoma (Cockerell & Eliot, 1905). Carmona et al. (2013) report this species from México. With these records from Málaga and Buenaventura, there is a considerable extension (ca. 4800 km southeast) in range distribution along the eastern Pacific for this species (Fig. 8f).

Limenandra confusa Carmona, Pola, Gosliner & Cervera, 2014. This species is known in the eastern Pacific from the Midway Islands, Hawaii, Mexico, Gulf of California, and Costa Rica (Bertsch 1972; Carmona et al. 2014b). This record (Fig. 9a) from Gorgona extends the distribution of the species by almost 480 km southward in the TEP.

Spurilla braziliana MacFarland, 1909. Carmona et al. (2014a) mention that in the eastern Pacific, this species has been reported from Costa Rica and Peru. This record (Fig. 9b) from Gorgona fills a gap in the distribution range of this species. The previous authors also report this species from the Colombian Caribbean, so this record confirms its presence on both coasts of Colombia.

Favorinus elenalexiae Garcia F. & Troncoso, 2001. Garcia and Troncoso (2001) report this species from the Gulf of California, Costa Rica, Panamá, and the Galápagos Islands. This record (Fig. 9c) from Gorgona fills a gap in the distribution of this species in the TEP.

Phidiana lascrucensis Bertsch & Ferreira, 1974. Bertsch and Ferreira (1974) report this species from Baja California to Costa Rica, Behrens, and Hermosillo (2005), and Camacho-García et al. (2005) add Panamá to its distribution range. The records (Fig. 9d) from Gorgona, Malaga, and Buenaventura, apart from showing the relative commonness of the species, extend its distribution range 400 km southward.

Fiona pinnata (Eschscholtz, 1831). This species is widely distributed, perhaps due to its natural history: drifting on floating objects. According to Behrens and Hermosillo (2005), it is cosmopolitan in northern seas. However, this Gogona record is, perhaps, the southernmost record for the species on the TEP (Fig. 10a).

Aplysiomorpha

Dolabella auricularia (Lightfoot, 1786). The records of this species are unclear, Camacho-García et al. (2005) report it for the tropical Pacific, while Behrens and Hermosillo (2005) consider it circumtropical. This species (Fig. 10b) is common (at night) on the Gorgona coral reef’s backreef and reef slope; during daylight, they have been found hiding in coral rubble.

Stylocheilus rickettsi (MacFarland, 1966). Behrens and Hermosillo (2005) and Camacho-García et al. (2005) report S. striatus for the TEP. However, Bazzicalupo et al. (2020) resurrect S. rickettsi as the species for the eastern Pacific. They examined specimens from southern Baja California (México), Costa Rica, and Panamá. Although there are no records from other localities (e.g. the Galápagos Islands), they propose a distributional range from Baja California to the Galápagos Islands. Hence, the records (Fig. 10c) from Gorgona could either be the southernmost record or fill a gap in its distribution along the TEP.

Sacoglossa

Polybranchia mexicana Medrano, Krug, Gosliner, Biju Kumar & Valdés, 2018. Medrano et al. (2019) noted that this species had been recorded from southern Baja California to the Galápagos Islands in the eastern Pacific, as P. viridis. In their revision of the genus, they propose P. mexicana as new species restricted to the eastern Pacific. This record (Fig. 10d) from Gorgona fills a distributional gap for the species in the TEP.

Discussion

Knowing how many species occur in any given region, ecosystem, or community is a monumental task, which can be challenging and elusive (Pimm 2012). But understanding such local patterns of biodiversity is essential to any management and conservation priorities. Human welfare depends upon the biodiversity of healthy ecosystems (Duarte 2000; Naeem et al. 2002; Benedetti-Cecchi 2006; Loreau and de Mazancourt 2013). On a global scale, across all phyla, figures regarding the number of species are even more difficult to obtain and compare (Bouchet et al. 2006; Mora et al. 2011; Appeltans et al. 2012). Different techniques and attempts (Gotelli and Colwell 2001; Foggo et al. 2003; Smith 2005; Fisher et al. 2015) have been implemented. There are several components to deal with. First, geographical: how many species occur within a given locality. Second, taxonomic: correctly identifying the species and describing new taxa. Third, functional: determine the roles played by each species, and their abundances and relative contributions. There is still a lot of work that needs to be done, both regionally and globally. The results of this investigation confirm that conclusion.

There is a relatively long history of Heterobranch research in certain regions of the eastern Pacific (Bertsch 2020); consequently, the diversity of this group is well known; however, this is not the case for the Colombian coast. Our knowledge of the marine fauna of the Colombian Pacific has a complex history. The area has endured a long period of isolation and accessibility restrictions (including security issues). Any inventories of the fauna and flora are still incomplete. Even the records of some species must be taken with caution, as the correct identification of species and distributional records can be inaccurate. Hopefully, this report, although far from complete, provides reliable data based on previous reports of peer-reviewed papers and information de novo.

The Chocó department shoreline is almost half of the entire Colombian Pacific coast. It runs for 3.1711° in latitude (more than 352 km). In this paper, there is only one new record from the Chocó northern littoral, Chromolaichma sedna at Cabo Marzo. The shoreline of Chocó is mostly rocky, an ecosystem ideal for many species of sea slugs. More research efforts in this region should increase the number of known species. Gorgona and Málaga are perhaps the most studied localities along the Pacific coast of Colombia, but heterobranch sea slugs, as inferred from the literature, have been overlooked. Malpelo is a very remote island, and logistic (and economic) restrictions hinder research in that locality. Although Buenaventura (where the major western port of Colombia is located) is the most accessible locality, the ecosystems there are mostly muddy flats, mangroves, and limestone cliffs, and the water has very low visibility and salinity. These are not the preferred habitats for most heterobranchs, especially the nudibranchs.

Most heterobranch species are small (less than 1 cm) and sometimes cryptic animals and can be overlooked in sampling efforts. More rigorous investigations will likely yield many more species.

The information in classical faunal compendia that encompass broad geographical regions (e.g., Keen 1971) suggests that more species are present in the Colombian Pacific. Many species have been reported both north and south of Colombia; their presumed presence here should be documented with further studies. Species reported only from Panamá or Ecuador may also be expected to occur in the Colombian littoral. Hence, one can expect a list of species longer than the one presented here. Colombian TEP marine biodiversity is not as huge as other regions in the world, but it certainly is much larger than currently known as demonstrated in this paper with this group of mollusks and warrants our continued investigation.

References

Adobe Photoshop (2021) Photoshop

Angulo-Campillo O, Bertsch H (2013) Marionia kinoi (Nudibranchia: Tritoniidae): a new species from the tropical eastern Pacific. Nautilus (philadelphia) 127:85–89

Appeltans W, Ahyong ST, Anderson G et al (2012) The magnitude of global marine species diversity. Curr Biol 22:2189–2202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.036

Ardila NE, Báez DP, Valdés Á (2007) Babosas y liebres de mar (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Opisthobranchia) de Colombia. Biota Colomb 8:185–197

Báez DP, Ardila N, Valdás Á, Acero PA (2011) Taxonomy and phylogeny of Armina (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia: Arminidae) from the Atlantic and eastern Pacific. J Mar Biol Assoc United Kingdom 91:1107–1121. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315410002109

Barber PH, Ablan-Lagman MCA, Ambariyanto A et al (2014) Advancing biodiversity research in developing countries: the need for changing paradigms. Bull Mar Sci 90:187–210. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2012.1108

Bazzicalupo E, Crocetta F, Gosliner TM et al (2020) Molecular and morphological systematics of Bursatella leachii de Blainville, 1817 and Stylocheilus striatus Quoy & Gaimard, 1832 reveal cryptic diversity in pantropically distributed taxa (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Heterobranchia). Invertebr Syst 34:535–568. https://doi.org/10.1071/IS19056

Behrens DW, Hermosillo A (2005) Eastern Pacific Nudibranchs: a guide to the Opisthobranchs from Alaska to Central America. Sea Challengers, Monterey, California, USA

Benedetti-Cecchi L (2006) Understanding the consequences of changing biodiversity on rocky shores: how much have we learned from past experiments? J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 338:193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2006.06.020

Bertsch H (2020) A history of eastern Pacific marine heterobranch research. Nautilus (philadelphia) 134:71–88

Bertsch H (2019) Biodiversity and natural history of Nudipleura communities (Mollusca, Gastropoda) at Bahía de los Ángeles, Baja California, Mexico. A 30-year study. Geomare Investig Terr y Mar 1:89–136

Bertsch H (2010) Biogeography of northeast Pacific opisthobranchs: comparative faunal province studies between Point Conception, California, USA, and Punta Aguja, Piura, Perú. In: L.J. Rangel-Ruíz, J. Gamboa-Aguilar SLA-W& WMC-S (ed) Perspectivas en Malacología Mexicana. Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco, La Paz, pp 219–259

Bertsch H (1978) The Chromodoridinae Nudibranchs from the Pacific coast of America - Part III. The Genera Chromolaichma and Mexichromis. The Veliger 21:70–86

Bertsch H (1972) Two additions to the Opisthibranch fauna of the southern Gulf of California. The Veliger 15:103–106

Bertsch H, Ferreira AJ (1974) Four new species of Nudibranchs from Tropical West America. The Veliger 16:343–353

Bouchet P (2006) The magnitude of marine biodiversity. In: Duarte CM (ed) The exploration of marine biodiversity scientific and technological challenges. Fundación BBVA, pp 31–64

Brusca RC, Moore W, Shuster SM (2016) Invertebrates, Third Edit. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA

Camacho-Garcia Y, Gosliner TM, Valdés Á (2005) Field guide to the sea slugs of the Tropical Eastern Pacific. California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco

Camacho-García YE, Gosliner TM (2004) A new species of Okenia (Gastropoda: Nudibranchia: Goniodorididae) from the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. Proc Calif Acad Sci 55:431–438

Camacho-García YE, Gosliner TM (2008) Nudibranch Dorids from the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica with the description of a new species. Bull Mar Sci 83:367–389

Cantera Kintz JR, López de Mesa LÁ, Cuéllar LM, Londoño-Cruz E (2011) Moluscos. In: Cantera Kintz JR, Londoño-Cruz E (eds) Colombia Pacífico: Una visión sobre su Biodiversidad Marina. Programa Editorial Universidad del Valle, Cali, pp 125–200

Cantera K. JR, Rubio R. EA, Borrero FJ, et al (1979) Taxonomía y distribución de los moluscos litorales de la Isla de Gorgona. In: Prahl H, Guhl F, Gröghl M (eds) Gorgona. Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá, pp 141–168

Carmona L, Lei BR, Pola M et al (2014a) Untangling the Spurilla neapolitana (Delle Chiaje, 1841) species complex: A review of the genus Spurilla Bergh, 1864 (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae). Zool J Linn Soc 170:132–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12098

Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL (2017) Integrative taxonomy and biogeography of the genus Bulbaeolidia (Nudibranchia: Aeolidida). J Molluscan Stud 83:440–450. https://doi.org/10.1093/mollus/eyx027

Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL (2013) A Tale That Morphology Fails to Tell: A Molecular Phylogeny of Aeolidiidae (Aeolidida, Nudibranchia, Gastropoda). PLoS One 8:e63000. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063000

Carmona L, Pola M, Gosliner TM, Cervera JL (2014) The end of a long controversy: systematics of the genus Limenandra (Mollusca: Nudibranchia: Aeolidiidae). Helgol Mar Res 68:37–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-013-0367-yAeolidiidae

Cosel R von (1985) Moluscos marinos de la Isla de Gorgona (Costa del Pacífico Colombiana). An del Inst Investig Mar Punta Betin 14:175–257

Costello MJ, Coll M, Danovaro R, et al (2010) A census of marine biodiversity knowledge, resources, and future challenges. PLoS One 5:e121110. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0012110

Dinapoli A, Klussmann-Kolb A (2010) The long way to diversity - phylogeny and evolution of the Heterobranchia (Mollusca: Gastropoda). Mol Phylogenet Evol 55:60–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2009.09.019

Duarte CM (2000) Marine biodiversity and ecosystem services: an elusive link. J Exp Mar Bio Ecol 250:117–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0981(00)00194-5

Fisher R, O’Leary RA, Low-Choy S et al (2015) Species richness on coral reefs and the pursuit of convergent global estimates. Curr Biol 25:500–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.12.022

Fisch KM, Hertzer C, Böringer N et al (2017) The potential of Indonesian heterobranchs found around Bunaken Island for the production of bioactive compounds. Mar Drugs 15:339–384. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15120384

Foggo A, Attrill MJ et al (2003) Estimating marine species richness: an evaluation of six extrapolative techniques. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 248:15–26

Furfaro G, Vitale F, Licchelli C, Mariottini P (2020) Two seas for one great diversity: Checklist of the marine heterobranchia (Mollusca; Gastropoda) from the Salento Peninsula (South-East Italy). Diversity 12:171. https://doi.org/10.3390/D12050171

Garcia FJ, Troncoso JS (2001) Favorinus elenalexiae, a new species (Opisthobrancha: Aeolidiidae) from the eastern Pacific Ocean. Nautilus (philadelphia) 115:55–61

Gotelli NJ, Colwell RK (2001) Quantifying biodiversity: procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol Lett 4:379–391

Hermosillo A (2006) Ecología de los Opistobranquios (Mollusca) de Bahía de Banderas, Jalisco-Nayarit, México. Universidad de Guadalajara

IDEAM (2019) Pronóstico de Pleamares y Bajamares en la costa Pacífica Colombiana. Bogotá, Colombia

INVEMAR (2020) Informe del Estado de los Ambientes Y Recursos Marinos y costeros de Colombia, Serie de P. Santa Marta

Kaiser KL, Bryce CW (2001) The recent molluscan marine fauna of Isla de Malpelo. Colombia the Festivus 33:158

Kaligis F, Eisenbarth JH, Schillo D et al (2018) Second survey of heterobranch sea slugs (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Heterobranchia) from Bunaken National Park, North Sulawesi, Indonesia - How much do we know after 12 years? Mar Biodivers Rec 11:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-018-0136-3

Keen M (1971) Sea shells of Tropical West America: marine mollusks from Baja California to Peru. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Second

López de Mesa LÁ, Cantera JR (2015) Marine mollusks of Bahía Málaga, Colombia (Tropical Eastern Pacific). Check List 11. https://doi.org/10.15560/11.1.1497

Loreau M, de Mazancourt C (2013) Biodiversity and ecosystem stability: a synthesis of underlying mechanisms. Ecol Lett 16:106–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12073

Lozano-Cortés D, Londoño-Cruz E, Izquierdo V et al (2012) Checklist of benthonic marine invertebrates from Malaga Bay (Isla Palma and Los Negritos), Colombian Pacific. Check List 8:703. https://doi.org/10.15560/8.4.703

Málikov I, Villegas-Bolaños NL (2005) Construcción de Series de Tiempo de Temperatura Superficial del Mar de las Zonas Homogéneas del Océano Pacífico Colombiano. Boletín Científico CCCP 12:79–93. https://doi.org/10.26640/01213423.12.79_93

Medrano S, Krug PJ, Gosliner TM et al (2019) Systematics of Polybranchia Pease, 1860 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Sacoglossa) based on molecular and morphological data. Zool J Linn Soc 186:76–115. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zly050

Mittermeier RA, Robles-Gil P, Hoffmann M, et al (2004) Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. CEMEX, Mexico City, Mexico

Mittermeier RA, Turner WR, Larsen FW et al (2011) Global biodiversity conservation: the critical role of hotspots. In: Zachos FE, Habel JC (eds) Biodiversity Hotspots. Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas. Springer, Berlin, pp 3–22

Mora C, Tittensor DP, Adl S et al (2011) How many species are there on earth and in the ocean? PLoS Biol 9:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127

Naeem S, Loreau M, Inchausti P (2002) Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: the emergence of a synthetic ecological framework. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: Synthesis and Perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 3–17

Nimbs MJ, Smith SDA (2018) Beyond capricornia: Tropical sea slugs (Gastropoda, Heterobranchia) extend their distributions into the Tasman Sea. Diversity 10:99. https://doi.org/10.3390/d10030099

Pimm SL (2012) Biodiversity: not just lots of fish in the sea. Curr Biol 22:R996–R997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2012.09.028

Pola M, Cervera JL, Gosliner TM (2005) Review of the systematics of the genus Roboastra Bergh, 1877 (Nudibranchia, Polyceridae, Nembrothinae) with the description of a new species from the Galápagos Islands. Zool J Linn Soc 144:167–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00167.x

Robertson R (1979) Philippia (Psilaxis) radiata: Another Indo-West-Pacific Architectonicid newly found in the Easter Pacific (Colombia). The Veliger 22:191–193

R Core Team (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/

Rangel-Ch. JO, Arellano-P. H (2004) El Chocó biogeográfico/Costa Pacífica de Colombia. In: Rangel-Che. JO (ed) Colombia Diversidad Biótica IV. Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Bogotá, pp 39–82

Schubert J, Smith SDA (2020) Sea slugs-"rare in space and time"-But Not Always. Diversity 12:1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/d12110423

Smith SDA (2005) Rapid assessment of invertebrate biodiversity on rocky shores: where there’s a whelk there’s a way. Biodivers Conserv 14:3565–3576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-0828-3

Undap N, Papu A, Schillo D et al (2019) First survey of heterobranch sea slugs (Mollusca, Gastropoda) from the Island Sangihe, North Sulawesi. Indonesia Diversity 11:170. https://doi.org/10.3390/d11090170

Uribe RA, Sepúlveda F, Goddard JHR, Valdés Á (2018) Integrative systematics of the genus Limacia O. F. Müller, 1781 (Gastropoda, Heterobranchia, Nudibranchia, Polyceridae) in the Eastern Pacific. Mar Biodivers 48:1815–1832. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-017-0676-5

Valdés Á (2002) A phylogenetic analysis and systematic revision of the cryptobranch dorids (Mollusca, Nudibranchia, Anthobranchia). Zool J Linn Soc 136:535–636. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00039.x

Valdés Á, Breslau E, Padula V et al (2018) Molecular and morphological systematics of Dolabrifera Gray, 1847 (Mollusca: Gastropoda: Heterobranchia: Aplysiomorpha). Zool J Linn Soc 184:31–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx099

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to my friend and colleague Jaime Cantera for his continuing support and encouragement towards the study of nudibranchs and the long talks regarding invertebrate biodiversity in general. He also read and improved this manuscript. I am especially grateful to my biology students at Universidad del Valle that knowing my passion for heterobranch sea slugs continuously pointed me towards these creatures whenever they spotted one. I am also indebted to my university that financially supported all the courses’ field trips. Finally, I want to express my deepest gratitude to my colleagues Maria Fernanda Cardona-Gutierrez, Luz Angela López de Mesa, and especially to Hans Bertsch that critically read, corrected, and enhanced this manuscript. Last but not least, three anonymous reviewers critically assessed the first version of the manuscript, and their contributions were reflected in a big improvement of this paper. This is contribution number 22 from INCIMAR.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study in particular; however, Universidad del Valle (Cali, Colombia) financially supported all the courses’ field trips in which most of the records were obtained. Other observations were made during various research projects financed by COLCIENCIAS and Universidad del Valle, grant numbers 1106–405-20155, “Biodiversidad de Estadios de Vida Vulnerable de Organismos Marinos en Bahía Málaga (Pacífico Colombiano) como criterio de conservación: Evaluación de la heterogeneidad de ambientes en la reproducción y reclutamiento,” and 1106–659-44216, “Relación entre las tasas de bioerosión y bioacreción de arrecifes coralinos de la Isla Gorgona, Pacifico colombiano”, and “Evaluación del estado actual de los objetos de conservación faunísticos en Isla Gorgona: una aproximación holística a la valoración ecológica del PNN Gorgona.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No animal testing was performed during this study.

Sampling and field studies

All necessary permits for sampling and observational field studies were obtained by the author from the competent authorities and are mentioned in the acknowledgements, if applicable. The study is compliant with CBD and Nagoya protocols.

Data availability

All available data, including pictures, is included in the manuscript.

Author contribution

Identification of samples, treatment of results, preparation, and writing of the whole paper were performed by the author.

Additional information

Communicated by C. Chen

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Londoño-Cruz, E. The contribution of Heterobranchia (Mollusca: Gastropoda) to the biodiversity of the Colombian Tropical Eastern Pacific. Mar. Biodivers. 51, 93 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-021-01230-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12526-021-01230-8