Abstract

Background

Recently, beneficial effects of probiotics and/or prebiotics on cardio-metabolic risk factors in adults have been shown. However, existing evidence has not been fully established for pediatric age groups. This study aimed to assess the effect of synbiotic on anthropometric indices and body composition in overweight or obese children and adolescents.

Methods

This randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted among 60 participants aged 8–18 years with a body mass index (BMI) equal to or higher than the 85th percentile. Participants were randomly divided into two groups that received either a synbiotic capsule containing 6 × 109 colony forming units (CFU) Lactobacillus coagulans SC-208, 6 × 109 CFU Lactobacillus indicus HU36 and fructooligosaccharide as a prebiotic (n = 30) or a placebo (n = 30) twice a day for eight weeks. Anthropometric indices and body composition were measured at baseline and after the intervention.

Results

The mean (standard deviation, SD) age was 11.07 (2.00) years and 11.23 (2.37) years for the placebo and synbiotic groups, respectively (P = 0.770). The waist-height ratio (WHtR) decreased significantly at the end of the intervention in comparison with baseline in the synbiotic group (0.54 ± 0.05 vs. 0.55 ± 0.05, P = 0.05). No significant changes were demonstrated in other anthropometric indices or body composition between groups.

Conclusions

Synbiotic supplementation might be associated with a reduction in WHtR. There were no significant changes in other anthropometric indices or body composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Childhood obesity is a global health concern. It is estimated that the prevalence of overweight in preschool children will increase to 11% worldwide by 2025 [1]. Pediatric obesity is associated with cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [2]. It increases the risk of adult-onset obesity. Obesity or overweight can reduce life expectancy or quality of life [3]. Treatment of obesity is more challenging than its prevention [4].

Several factors, including genetic susceptibility and environmental factors, are associated with obesity. Some modifiable factors, such as lifestyle and diet, are important for national prevention policies. The gut microbiota is a new point of interest that plays a role in the pathophysiology of obesity. It is associated with body weight control, energy homoeostasis, host energy storage and inflammation [5]. Some lifestyle factors, including lack of exercise, smoking habits and stress, can alter gut microbiota composition. Dietary habits and the composition of nutrients have been suggested as the main geographical factors associated with gut microbiota composition. Some nutrients and bioactive compounds, including probiotics (including yogurts) and prebiotics (fibers and polyphenols), influence the microbiome. Unhealthy dietary patterns, such as Western diets, have been associated with the development of obesity and induce gut dysbiosis [6]. The amount and type of energy source can impact the composition of gut microbiota [7, 8]. Studies have shown reduced levels of Clostridium perfringens and Bacteroidetes in obese subjects compared to lean subjects. Bacteroides thetaiotamicron in association with Methanobrevibacter smithii increases adipose tissue accumulation. An imbalanced Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, associated with an increase in the Actinobacteria phylum and a decrease in Verrucomicrobia in obesity, was confirmed [9]. The findings suggested a dose-dependent association between certain species of bacteria and obesity. In particular, there is a clear relationship between the number of Lactobacillus reuteri cells and obesity. Excess weight is associated with a higher number of L. reuteri [10].

Human and animal studies have shown that the composition of gut microbiota varies in obese and lean subjects. The major types of bacteria in the body are Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. Firmicutes is more abundant than Bacteroidetes in obese people [7]. Thus, decreasing Firmicutes and increasing Bacteroidetes will be helpful for obese people.

Nutritional interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics (a mixture of probiotics and prebiotics) can improve the gut microbiota [11]. Synbiotics have the simultaneous properties of probiotics and prebiotics and may influence the survival of probiotics in the gastrointestinal tract [12]. Therefore, a suitable combination of both probiotics and prebiotics in a single product might have a better impact on host health in comparison with the separate activity of probiotics or prebiotics [13]. However, some studies did not show any significant effects of synbiotics on weight and body mass index (BMI) [14, 15].

Different strains of the probiotic family have shown various impacts on cardio-metabolic risk factors, including obesity [16]. A combination of several strains is likely to be more effective than one strain. The present study aimed to determine the potential effects of synbiotic supplementation on anthropometric indices and body composition in overweight or obese children and adolescents.

Methods

Study design

This project was a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. It was conducted on 60 overweight or obese children aged between 8 and 18 years with a body mass index (BMI) equal to or higher than the age- and sex-specific 85th percentile according to the World Health Organization percentiles [17]. Use of antibiotics during the previous three months, having any chronic disease, including diabetes, thyroid disorders, cardiovascular diseases, digestive problems, pancreatic and liver diseases, and non-compliance with the intervention regularly were exclusion criteria. Individuals’ compliance with the intervention was assessed by counting the number of capsules remaining in each package (compliance = consuming at least 90% of the capsules delivered during the study) and by weekly phone interview. Additionally, those with a daily diet above 4200 Kcal and below 800 Kcal were excluded from the study [18]. Participants were randomly allocated into two groups, synbiotic and placebo. Participants were randomly assigned based on the permutated block randomization method. The random allocation was carried out using a table of random numbers.

The sample size in the current study was determined using a formula for a parallel design randomized controlled trial in which type I and II error rates were considered 5 and 20% (statistical power of 80%), respectively, and the minimum detectable standardized effect size was considered 0.75 [19]. We considered a 33% additional sample size to cover the potential dropout rates. Finally, 40 individuals were included in each group.

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the research and ethics committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The trial was registered, and the number of registrations is IRCT20170501033747N2. A written informed consent form was obtained from parents, and oral assent was obtained from their children after the aims and procedures were explained.

Supplement administration

The synbiotic group received two daily capsules containing 12 × 109 colony forming units (CFU) of probiotics (6 × 109 CFU: Lactobacillus coagulans SC-208, 6 × 109 CFU Lactobacillus indicus HU36). The prebiotic was short-chain fructooligosaccharide (FOS), and each capsule included 38.5 g FOS (7.7% of each capsule).

Those in the placebo group received two 0.5 g capsules containing maltodextrin. Participants consumed two capsules daily with enough water before lunch and dinner. Synbiotic supplements and the placebo were provided by Shiraz Mehregan Campus Growth Bio products Company, Shiraz, Iran. The manufacturer assigned synbiotic supplement and placebo into A and B codes and packed them in the same boxes in terms of color, shape and size.

They were also advised to store the supplements in a refrigerator to preserve the bacterial load. Additionally, they refrain from consuming fermented products and foods containing probiotics.

Dietary and physical activity assessment

Dietary intake was evaluated by three-day dietary records at the beginning and the end of the study. Dietary data were analyzed by Nutritionist IV software (First Databank, San Bruno, CA, USA). Data entry was performed by a trained dietitian.

Physical activity was assessed by International Physical Activity Questionnaires (IPAQ) [20]. The questions ask about the time of physical activity during the last seven days. Intensity of activity (i.e., vigorous or moderate) and sedentary behaviors such as watching TV were questioned.

Additionally, participants were advised not to change their usual diet and physical activity during the study period.

Anthropometric measurement assessments

Height was measured by a trained nutritionist to the nearest 0.1 cm with a portable stadiometer (SECA, Hamburg, Germany) without shoes. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg with a balanced portable digital weight scale (SECA, Hamburg, Germany) with light indoor clothing and no shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg)/height2 (m). Waist circumference (WC) was measured over the unclothed abdomen at the narrowest point between the rib cage and the superior border of the iliac crest using a nonelastic flexible tape to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Hip circumference (HC) was measured at the widest part of the hip at the level of the greater trochanter to the nearest 0.1 cm. Wrist circumference (WrC) was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm on the dominant arm using a tape meter. Neck circumference (NC) was measured with the most prominent portion of the thyroid cartilage taken as a landmark to the nearest 0.1 cm. The waist-height ratio (WHtR), waist-hip ratio (WHR), abdominal volume index (AVI), conicity index (CI), and a body shape index (ABSI) were calculated using the following formulas:

Body composition analysis

Bioelectrical impedance analysis was performed using an InBody 720 Body Composition Analyzer (BioSpace Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea). Sex, age, and height were entered directly into the instrument prior to the impedance measurement. Bare feet were placed on the metal plates of the scale, and the participant firmly grasped the hand grips while placing the thumb and fingers in the standard location as indicated in the operation manual. The InBody uses eight points of tactile electrodes (contact at the hands and feet), and it detects the amount of segmental body water. The technique uses multiple frequencies to measure intracellular and extracellular water separately. Thirty impedances are measured in five parts (right arm, left arm, right leg, left leg and trunk) using six frequency bands (1, 5, 50, 250, 500 and 1000 kHz). Frequencies below 50 kHz measure extracellular water, whereas frequencies above 50 kHz measure total body water. The impedances obtained at each frequency are combined to measure intracellular water and extracellular water. After calculating the body water content by the impedance method, the protein mass (muscle) and the mineral mass (bone) are derived from the body water, and the body fat mass is obtained by subtracting these three components from the body weight. It also calculates skeletal muscle mass.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for quantitative variables and number (percentage) for qualitative variables. After assessment of the normal distribution by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, within-group changes were compared by the paired t test. For comparison of data between the two groups, we used an independent t test for data with a normal distribution. The interaction effect of gender and intervention was assessed by analysis of covariance adjusted for baseline values. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used SPSS for Windows software (version 20; SPSS, Chicago, IL) for statistical analysis.

Results

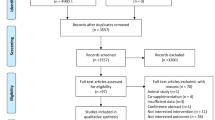

Among 80 subjects, 7 subjects in the placebo group and 13 in the synbiotic group dropped out. Twelve participants had to take antibiotics due to viral diseases. Five participants did not want to continue taking the drug for personal reasons, and digestive problems occurred in three participants. A total of 60 subjects (32 girls and 28 boys) completed the study and were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1). The mean (SD) age was 11.07 (2.00) years and 11.23 (2.37) years for the placebo and synbiotic groups, respectively (P = 0.770). Baseline characteristics at the beginning of the study did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 1). Baseline carbohydrate intake was significantly different between the two groups. However, there were no significant differences in energy and other nutrient intake within and between groups (Table 2).

There were no significant differences between anthropometric values in the placebo and synbiotic groups at baseline (P > 0.05, Table 3). The mean WHtR was significantly different before and after the intervention in the synbiotic group (P = 0.05). There were no significant differences between the mean changes in anthropometric indices between the two groups (P > 0.05, Table 3).

Body composition was measured at baseline and at the end of the intervention. No significant differences were observed between the other anthropometric indices between the two groups. Body composition was assessed at baseline and after the intervention. However, there were no significant changes between and within groups (Table 4). Sex-stratified analysis revealed no significant changes in anthropometric indices or body composition after the intervention in either sex (Table 5).

Discussion

The present study aimed to assess whether a synbiotic combination of L. coagulans SC-208 and L. indicus HU36 with FOS was effective on anthropometric indices and body composition in overweight or obese children and adolescents. Our results showed that WHtR significantly decreased at the end of the intervention in the synbiotic group in comparison with baseline. No significant changes were demonstrated in other anthropometric indices or body composition between groups.

The results of a recent meta-analysis showed no effect of pro/synbiotic supplementation on BMI, weight, body fat percent and WC among adults with metabolic syndrome [21]. However, another meta-analysis of 23 randomized trials showed that supplementation with a synbiotic can decrease body weight and WC [22]. The reason for the difference in the results may be that the difference in the selected population and the type of intervention.

There are limited human studies that have assessed the effects of probiotics on obesity and anthropometric indices, particularly among pediatric age groups. One month of intervention with synbiotic significantly decreased weight and BMI in obese children and adolescents [23]. Eight weeks of intervention with synbiotic without any lifestyle manipulation reduced BMI z score, WC and waist-to-hip ratio [24]. Eight weeks of intervention with Lactobacillus rhamnosus in obese children with liver disease showed that L. rhamnosus strain GG altered the bacterial composition without any remarkable effect on BMI z score or visceral fat [25]. However, 12 weeks of intervention with Lactobacillus salivarius (Ls-33) did not show any significant influence on BMI z score, WC or body fat in adolescents [26]. Three months of intervention with probiotics [Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CECT 8145 (Ba8145)] improved WC, WC/height ratio, conicity index, BMI and visceral fat among adults [27]. Another 12 weeks of intervention with probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17) showed a slight weight reduction and significant waist and hip circumference changes among obese adults [28], and 12 weeks of intervention with L. gasseri SBT2055 showed a beneficial impact on abdominal adiposity and body weight among adults [29]. The differences between our results and other studies could be due to diversity in probiotic strain, composition and dose of supplement, subjects’ characteristics, geographical differences, and duration of the intervention.

Animal studies showed that probiotic supplementation with L. gasseri, Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032 could decrease abdominal obesity and white adipose tissue size. It may be correlated with a reduction in leptin and adiponectin levels and an increase in the expression of fatty acid oxidation-related genes [30,31,32]. These findings reveal the effects of probiotics on the modulation of the natural gut microbiota [33]. Evidence has suggested that an imbalance in gut microbiota could contribute to overweight and obesity [22]. Weight loss with a calorie-restricted diet accompanied by increased physical activity has favorable effects on gut microbiota composition [34]. Although the pathogenesis and mechanisms underlying excess adiposity are complex, manipulation of the bacteria in the gastrointestinal system can be considered a potential therapy for overweight and obesity [22].

Initial diversity in the gut microbiota composition in children could be associated with overweight development in adulthood. The impact of probiotics on gut microbiota composition during the first year of life was shown to be a preventive factor for childhood obesity [35]. Intake of L. rhamnosus for four weeks before delivery and six months postnatally prevented severe weight gain during the first years of life [36].

The intestinal microbiota increases short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including acetate, butyrate and propionate. G-protein coupled receptors 43 and 41 (GPR43 and GPR41) are considered key receptors for SCFA. These two receptors impact the secretion of pancreatic peptide YY (PYY) hormone and leptin and ultimately influence appetite and weight gain [37].

Acetate directly influences the hypothalamus and reduces appetite. Some gut microbiota compounds can suppress the expression of fasting-induced adipose factor (FIAF) protein. This glycoprotein inhibits the production of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in adipose tissue and the oxidation of fatty acids in both muscle and skeletal muscle [38].

However, the findings are still contradictory, and some mechanisms are controversial. Therefore, further investigation is necessary. The effects of dietary changes and supplements on the human gut microbiota are highly individualized. Findings of the interaction between diet–microbiota and host genetics and epigenetics help us plan new personalized diet approaches and implement new personalized strategies to prevent and decrease the incidence of obesity and other non-communicable diseases [39]. The advantages of the present study are the difference in probiotic strain and pediatric age groups. We assessed several anthropometric indices and body composition.

Intervention during the global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) along with home quarantine and the inability to study enough molecular parameters to reveal molecular mechanisms are limitations of the present study. Our study included children and adolescents, and this age range has a differential impact on gut microbiota. Synbiotic supplements in our study were a combination of two different species, so we could not determine the singular effect and the possible synergistic or antagonistic effects of them. In addition, some studies [24, 28] used the fecal count of gut microbiota to confirm probiotic intake-related changes in intestine flora, but fecal samples were not taken in our study because of financial problems.

In conclusion, synbiotic supplementation might be associated with a reduction in WHtR. Further large-scale studies are required to highlight the importance of the synbiotic on cardio-metabolic risk factors in pediatric age groups.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Heidari-Beni M, Kelishadi R. Prevalence of weight disorders in iranian children and adolescents. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:511–5.

Daniels SR. Complications of obesity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33:S60–5.

Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366:1197–209.

Al Dhaifallah A, Mwanri L, Aljoudi A. Childhood obesity in Saudi Arabia: opportunities and challenges. Saudi J Obesity. 2015;3:2.

Petraroli M, Castellone E, Patianna V, Esposito S. Gut microbiota and obesity in adults and children: the state of the art. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:657020.

Redondo-Useros N, Nova E, González-Zancada N, Díaz LE, Gómez-Martínez S, Marcos A. Microbiota and lifestyle: a special focus on diet. Nutrients. 2020;12:1776.

Bervoets L, Van Hoorenbeeck K, Kortleven I, Van Noten C, Hens N, Vael C, et al. Differences in gut microbiota composition between obese and lean children: a cross-sectional study. Gut Pathog. 2013;5:10.

Chang L, Neu J. Early factors leading to later obesity: interactions of the microbiome, epigenome, and nutrition. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2015;45:134–42.

Duranti S, Ferrario C, van Sinderen D, Ventura M, Turroni F. Obesity and microbiota: an example of an intricate relationship. Genes Nutr. 2017;12:18.

Sharma R, Mokhtari S, Jafari SM, Sharma S. Barley-based probiotic food mixture: health effects and future prospects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62:7961–75.

Barengolts E. Gut microbiota, prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in management of obesity and prediabetes: review of randomized controlled trials. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:1224–34.

Markowiak P, Śliżewska K. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients. 2017;9:1021.

Gurry T. Synbiotic approaches to human health and well-being. Microb Biotechnol. 2017;10:1070–3.

Anggeraini AS, Massi MN, Hamid F, Ahmad A, As’ad S, Bukhari A. Effects of synbiotic supplement on body weight and fasting blood glucose levels in obesity: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;68:102548.

Rabiei S, Hedayati M, Rashidkhani B, Saadat N, Shakerhossini R. The effects of synbiotic supplementation on body mass index, metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers, and appetite in patients with metabolic syndrome: a triple-blind randomized controlled trial. J Diet Suppl. 2019;16:294–306.

Park DY, Ahn YT, Huh CS, McGregor RA, Choi MS. Dual probiotic strains suppress high fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:274–83.

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–7.

Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Majdzadeh R, Hosseini M, Gouya MM, et al. Thinness, overweight and obesity in a national sample of Iranian children and adolescents: CASPIAN Study. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34:44–54.

Çakır M, Aksel İşbilen A, Eyüpoğlu İ, Sağ E, Örem A, Mazlum Şen T, et al. Effects of long-term synbiotic supplementation in addition to lifestyle changes in children with obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28:377–83.

Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Gheiratmand R, Gouya MM, Razaghi EM, Delavari A, et al. Association of physical activity and dietary behaviors in relation to the body mass index in a national sample of Iranian children and adolescents: CASPIAN Study. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:19–26.

Hadi A, Arab A, Khalesi S, Rafie N, Kafeshani M, Kazemi M. Effects of probiotic supplementation on anthropometric and metabolic characteristics in adults with metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2021;40:4662–73.

Hadi A, Alizadeh K, Hajianfar H, Mohammadi H, Miraghajani M. Efficacy of synbiotic supplementation in obesity treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60:584–96.

Ipar N, Aydogdu SD, Yildirim GK, Inal M, Gies I, Vandenplas Y, et al. Effects of synbiotic on anthropometry, lipid profile and oxidative stress in obese children. Benef Microbes. 2015;6:775–82.

Safavi M, Farajian S, Kelishadi R, Mirlohi M, Hashemipour M. The effects of synbiotic supplementation on some cardio-metabolic risk factors in overweight and obese children: a randomized triple-masked controlled trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2013;64:687–93.

Vajro P, Mandato C, Licenziati MR, Franzese A, Vitale DF, Lenta S, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus strain GG in pediatric obesity-related liver disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:740–3.

Gøbel RJ, Larsen N, Jakobsen M, Mølgaard C, Michaelsen KF. Probiotics to adolescents with obesity: effects on inflammation and metabolic syndrome. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:673–8.

Pedret A, Valls RM, Calderón-Pérez L, Llauradó E, Companys J, Pla-Pagà L, et al. Effects of daily consumption of the probiotic Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis CECT 8145 on anthropometric adiposity biomarkers in abdominally obese subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond). 2019;43:1863–8.

Jung SP, Lee KM, Kang JH, Yun SI, Park HO, Moon Y, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on overweight and obese adults: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34:80–9.

Kadooka Y, Sato M, Imaizumi K, Ogawa A, Ikuyama K, Akai Y, et al. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:636–43.

Kang JH, Yun SI, Park HO. Effects of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on body weight and adipose tissue mass in diet-induced overweight rats. J Microbiol. 2010;48:712–4.

Million M, Lagier JC, Yahav D, Paul M. Gut bacterial microbiota and obesity. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:305–13.

Yun SI, Park HO, Kang JH. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 on blood glucose levels and body weight in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. J Appl Microbiol. 2009;107:1681–6.

Park DY, Ahn YT, Park SH, Huh CS, Yoo SR, Yu R, et al. Supplementation of Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032 in diet-induced obese mice is associated with gut microbial changes and reduction in obesity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59470.

Santacruz A, Marcos A, Wärnberg J, Martí A, Martin-Matillas M, Campoy C, et al. Interplay between weight loss and gut microbiota composition in overweight adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17:1906–15.

Kalliomäki M, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Early differences in fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:534–8.

Luoto R, Kalliomäki M, Laitinen K, Isolauri E. The impact of perinatal probiotic intervention on the development of overweight and obesity: follow-up study from birth to 10 years. Int J Obes (Lond). 2010;34:1531–7.

Shakeri H, Hadaegh H, Abedi F, Tajabadi-Ebrahimi M, Mazroii N, Ghandi Y, et al. Consumption of synbiotic bread decreases triacylglycerol and VLDL levels while increasing HDL levels in serum from patients with type-2 diabetes. Lipids. 2014;49:695–701.

Graham C, Mullen A, Whelan K. Obesity and the gastrointestinal microbiota: a review of associations and mechanisms. Nutr Rev. 2015;73:376–85.

Cuevas-Sierra A, Ramos-Lopez O, Riezu-Boj JI, Milagro FI, Martinez JA. Diet, gut microbiota, and obesity: links with host genetics and epigenetics and potential applications. Adv Nutr. 2019;10:S17–30.

Funding

This study was conducted as the project number 298113 supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HBM, KR and SJF: conceptualization, writing–review and editing. HBM: formal analysis. AMA: writing–original draft. EMH: review and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No financial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Research ethics code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1398.449).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Atazadegan, M.A., Heidari-Beni, M., Entezari, M.H. et al. Effects of synbiotic supplementation on anthropometric indices and body composition in overweight or obese children and adolescents: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. World J Pediatr 19, 356–365 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00664-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12519-022-00664-9