Abstract

Modern American Judaism is often characterized by complex negotiations about practices, beliefs, affiliations and identities. This article uses ethnographic research on one ritual practice—the Mi Sheberach prayer for healing—to explore these processes of meaning-making and identity construction, through the lens of lived experience. While survey data tell us which practices, beliefs and affiliations are most commonly adopted by liberal American Jews, this ethnographic research examines why these choices are made, what they represent, and how they are integrated into the broader lifeworlds of this population. I demonstrate that prayers for healing are an inherently social process, inextricably linked to relationships with other people, the community, God, and tradition. Prayer means something different to each of the participants in this study, yet for all, the Mi Sheberach becomes one site, among many, through which relationships to Judaism and Jewishness are negotiated and constructed. Study participants choose, and maintain, those Jewish practices, like the Mi Sheberach, that resonate emotionally and/or spiritually and that fit within the larger context of their lifeworld—in this case, the search for meaning, comfort, strength and connection during times of illness and healing. Yet at the same time, an essential part of this resonance is the experience of community, connection and tradition. The individual’s search for meaning is synthesized with the collectivist nature of Judaism, in an ongoing and continually evolving process of interpretive interaction between text, tradition and personal experience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the early winter of 2014, I attended the monthly meeting of a support group for Jewish women with cancer in Tucson, Arizona. I was there to recruit women for my study on Jewish prayer and healing. In response to my inquiries, one woman told me, “I don’t pray.” Another said, “I’m not religious at all.” Several women told me, “We’re not sure we can help you.” At the close of the meeting, the women all got up from their seats and stood in a circle at the side of the room, holding hands, shoulders and hips touching. Eyes closed, they began to sing a modern version of the Mi Sheberach, the Jewish prayer for healing. This variation was written about 30 years ago, by the Jewish liturgical singer-songwriter Debbie Friedman:

Mi Sheberach avoteynu (the one who blessed our fathers)

Makor habrakha l’imoteynu (source of strength for our mothers)

May the Source of Strength

Who blessed the ones before us

Help us find the courage

To make our lives a blessing,

And let us say: Amen.

Mi Sheberach imoteynu (the one who blessed our mothers)

Makor habrakha l’avoteynu (source of strength for our fathers)

Bless those in need of healing

With r’fuah shleymah: (whole healing)

The renewal of body

The renewal of spirit,

And let us say: Amen.

As the song came to an end, the hands holding each other lingered a little longer. There were gentle squeezes, then a slow letting go, a shoulder rub, a hug, and a few small conversations, and then the women left to go on with their day. Afterward, I was chatting with one of the women. She told me that she doesn’t pray. “What about that?” I asked, referring to the closing with Mi Sheberach. There was a thoughtful pause. “Oh,” she said, “I love that. It’s my favorite part of the morning. I guess you’re right. That is prayer. I hadn’t thought of it that way.” Later, another woman, who describes her Judaism as peripheral to her life, saying that she is mostly an ethical Jew, but not at all a religious one, told me this: “When we’re all together, holding hands and swaying, when I hear the Mi Sheberach… something in me just responds. I guess it’s my Jewish genes! We have so much love for each other in the group, and we are just surrounded by that love right then. It’s so beautiful.”

My attendance at the support group meeting was part of the ethnographic fieldwork I conducted from 2013 to 2015 to explore prayer and healing among liberal (non-Orthodox) Jews in Southern Arizona. I had been trying to understand why nonreligious Jews like the women at this support group pray, and why they pray for healing. My focus was on paying attention to the lived experience of Jewish prayer, and on trying to understand how participants themselves interpreted its effects. Rather than trying to determine whether prayer “works,” I asked this: “What does prayer do?” I am particularly interested in what Jewish prayer does and means at a time characterized by an increasingly personalized approach to Jewish beliefs, practices, and identities (Liebman 2005). As Cohen and Eisen (2000) note, participation in both ritual and prayer practices is now based in personal choice and the desire for an individually meaningful experience, rather than in a belief in God or communal obligation: “The words in the prayer book do not particularly interest them. The God described and invoked in those prayers is very different from the one in which they believe…They are distinctly uncomfortable with the act of prayer. And yet they pray” (Cohen and Eisen 2000: 155). Given this context, how can we understand the growing popularity of these prayers for healing? What does recitation of these prayers mean to those who choose to say them? And what can practices like the recitation of the Mi Sheberach teach us about the meaning of prayer and healing, and about being Jewish in America today?

In this article, I first present a brief overview of the current thinking about Jewish identity, as well as background information about Jewish prayers for healing. I then describe the effects of these prayers, as described by the participants themselves, focusing on their own experiences, interpretations, and meanings. I conclude the paper with a discussion of the implications of this research for our understanding of Jewishness and Jewish practice in 21st-century America.

Background

The Changing Dynamics of Jewish Identity in 21st-century America

Jewish identity is a central concern of the social scientific study of American Jewry, as scholars have extensively debated both what Jewish identity means and how to study it. The terms “Judaism,” “Jewishness,” and “Jewish identity” have been used historically and socially to refer to a diverse array of identifications, beliefs, practices, and social dynamics. Following Asad (1993) and MacIntyre (1981), I approach Judaism here as a religious tradition—a set of practices and discourses (and discourses about practices) that construct ethical selves. Furthermore, this “discursive tradition” is based in a set of relationships among the past, foundational texts and commentaries, and key leadership figures. As described by Horowitz (2000), Jewishness and Jewish identity refer to the subjective, internal self-understanding of what Judaism means in a person’s life.

Much of the social scientific research on Jewish identity has approached identity as a coherent, authentic, easily bounded, reified product that can be created, taught, and measured (Charmé et al. 2008; Charme and Zelkowicz 2011; Kelman 2012; Zelkowicz 2013). This work has often focused on a normative set of beliefs, behaviors, and affiliations, although what is included in these norms (and therefore what is measured) has shifted over the years. More recently, scholars have recognized that identity is inherently unstable, a socially constructed product of historical and cultural forces. Jonathan Krasner (2014) puts it this way:

It turned out that identity was fluid rather than stable, transient rather than enduring, hybrid and overlapping rather than distinct and impermeable. Moreover, individuals inhabited multiple identities and often treated ethnic identity symbolically. Decisions about which one(s) to emphasize were provisional, situational and circumstantial in nature. … [I]n the post-modern world, when identity can be merely symbolic and momentary, identity becomes a poor substitute for lived experience, for practice.

Ethnographic and narrative approaches are particularly well-suited to capturing the complexities of these fluid and ever-changing identities and practices (Horowitz 2002; Prell 2000), allowing the researcher to explore the ways in which relationships to Judaism, Jewish institutions and Jewish practice change over time (Heilman 2000). Such research can help us to shed light on the many different ways in which people make meaning of Judaism over the course of their lives, as well as the variable social contexts and other identities that influence how different forms of Jewishness are constructed and negotiated (Charmé et al. 2008; Cohen and Eisen 2000; Horowitz 2002; Prell 2000). Rather than limiting Jewish identity to a particular list of behaviors or beliefs, seen as important and deemed to be “authentic” by researchers, rabbis, and/or communal leaders, ethnography makes room for the dissonance, tensions, and multiple forms of agency within the processes of Jewish-identity formation (Hyman 2004; Zelkowicz 2013). Such a focus on the lived experience of religion and religious practice recognizes the following, in the words of Robert Orsi:

Religious practices and understandings have meaning only in relation to other cultural forms and in relation to the life experiences and actual circumstances of the people using them; what people mean and intend by particular religious idioms can be understood only situationally, on a broad social and biographical field, not within the terms of a religious tradition or religious language understood as existing apart from history (2002: xx).

A focus on lived Judaism, therefore, allows the meaning of Jewishness and Jewish identity to emerge from the experiences of those living them, within the full contexts of their own lifeworlds (Brink-Danan 2008).

A growing body of literature has emerged that uses ethnographic methods to understand the construction of modern Jewishness (Boyarin 2011; Brink-Danan 2012; Buckser 2003; Bunin Benor 2012; Fader 2009; Kugelmass 1988; Seeman 2009). These studies move beyond both textual and institutional discourses, and reveal the complicated and often contradictory negotiations that individuals engage in as they make choices about their Jewish lives. For example, ethnographic studies have shed light on the divergence between the perspectives of policymakers and individuals (Thompson 2013) as well as on the role of gender in the evolving Jewish family (Kahn 2000; McGinity 2009). Ethnographic methods are also being used to study new and emerging rituals (Mehta 2015; Neriya-Ben Shahar 2015; Prell 1989; Rothenberg 2006) and to explore the complexities of Jewish beliefs and practices (Heilman 2000; Silverman et al. 2016). They have demonstrated that, for many non-Orthodox American Jews, being Jewish is both ascribed and achieved; that is to say, being Jewish is not perceived as a choice, but the ways in which one expresses one’s Jewishness is. Davidman, for example, has documented “unsynagogued” American Jews, describing them as having “adopted and adapted various rituals and traditions as frameworks for creating their own ways of giving meaning to their Judaism” (Davidman 2007: 33). The complex negotiations embedded in such expressions of Jewishness are the focus of the research presented here, which seeks to understand the meaning and impact of Jewish ritual through the lens of lived experience. By examining one ritual practice that has been widely adopted and adapted by liberal American Jews, I explore how choices about practice and belonging are made, what they represent, and how they are integrated into the broader experiences of this population. The ethnographic approach thus allows us to better understand why liberal Jews turn to rituals and prayers of healing at times of illness, and how these prayers facilitate the construction of one’s Jewish identity.

Judaism, Prayer, and Healing

Ethnographers of religion have found that American religious practices for healing are rarely practiced in isolation, but are part of a pluralistic and diverse approach to healing (Barnes 2011; Barnes and Sered 2005). Liberal Jews, much like middle-class suburbanites (McGuire 1988) and liberal Protestants (Klassen 2011), integrate Jewish traditions, practices, and beliefs with discourses and practices from an increasingly medicalized modern society—one that offers a wide range of psychotherapeutic, energetic, and complementary therapies—and from other religious traditions, in eclectic and individual ways (Rothenberg 2006; Sered 2005). One of these practices is the Mi Sheberach, the Jewish prayer for healing.

The Hebrew phrase Mi Sheberach literally means “the one who blessed.” Although many Jewish prayers begin with this formula, one of the most well-known among modern American Jews is the Mi Sheberach, which is said for an ill person: “May the One who blessed our ancestors bless this person with a quick and full recovery, a healing of body and of soul.” The traditional Mi Sheberach is said at a prescribed moment in the midst of the reading from the Torah during the Shabbat morning service. Traditionally, the community recites the prayer on behalf of someone who is seriously ill. The recitation lasts a brief moment, a few minutes out of a three-hour service. Yet, over the last 30 years, since the introduction of Debbie Friedman’s version of the prayer, the Mi Sheberach has come to occupy a central place in liberal Jewish ritual and imagination (Cutter 2011a, b). Synagogues now keep “Mi Sheberach lists” (with the names of members who are ill) that are read during weekly services. In some synagogues, all those with ill family members or friends line up during the Torah reading, and the rabbi recites the prayer. In others, particularly within the more liberal denominations (Reform, Conservative, Reconstructionist, Jewish Renewal) the rabbi asks congregants to call out the names of anyone who needs healing of body or spirit. Then the congregation sings the prayer together, often holding hands. At some synagogues, the traditional prayer, which asks for r’fuah sh’leimah: r’fuat haguf v’r’fuat hanefesh (“whole healing, healing of body, healing of spirit”), is chanted. At others, Friedman’s version is sung, with its combination of Hebrew and English gender-neutral language and its call for “renewal of body, renewal of spirit,” rather than physical cure. Some congregations simply use this chant: Anah, el na refah na lah (“Please God, heal her now”), adapted from the biblical verse (Numbers 12:13) in which Moses prays for the health of his sister, Miriam.

In addition, multiple new Jewish prayers for healing have emerged in recent years. Specific versions of the Mi Sheberach have been created for caregivers, health-care providers, those undergoing different types of procedures, and those living with chronic conditions. These prayers for healing are now recited not only in synagogues, but also in hospital rooms, during support-group meetings and meditation classes, and at dedicated chanting circles. They are recited for individuals, groups, and communities. A number of essays and commentaries have been written about this prayer in recent years. Almost all of them clearly make this statement: We are not praying for physical cure; we are not asking God (whatever we understand God to be) to cure only those we are praying for. We are praying for healing, which can come in many forms (Cutter 2011a, b; Pelc Adler 2011). Jewish leaders are eager to differentiate themselves from “faith healers” in the Pentecostal Christian tradition, and they emphasize that they do not claim to heal bodies. Rather, they focus on the use of Jewish resources and traditions to address the emotional and spiritual aspects of illness and loss (Cutter 2011a, b; Sered 2005). In an essay about prayer during the High Holidays, Rabbi Rachel Cowan (a Reform rabbi) makes this observation:

Jewish healing practices teach us to look for the meaning of our lives even in the midst of pain and fear. We pray for refuat hanefesh, healing of the soul as well as refuat haguf, healing of the body. They teach us to relinquish our story of suffering, to define ourselves as more than our illness, more than our loss. They teach an awareness of beauty as well as an acceptance of pain (Cowan 1997: 277).

Similarly, in the introduction to a 2013 collection of modern Jewish prayers for healing, published by the Union for Reform Judaism, Rabbi Eric Weiss offers this comment:

All healing is a journey towards wholeness. Most of us know ourselves best when we are healthy and well. When we become ill, we are suddenly estranged from our familiar surroundings and often from ourselves. It is as if we are in foreign terrain with no guide…. Spiritual reflection – in prayer or ritual – is the form that allows us to link our history to our personal story. It is a glimpse into a moment of life that longs to be held, to find comfort, to strive toward wholeness (Weiss 2013: xx).

It is important to note that almost no one in my study had read these, or any, of the many essays or books published within the last 20 years that explore Judaism, health, and healing. (See, for example, Cutter 2007; Cutter 2011a, b; Freeman and Abrams 1999; Levin and Prince 2010; Person 2003; Rosman 1997; Weintraub 1994.) While their interpretations may resonate with these perspectives (as I describe below), their understanding emerged out of their own experiences, and was not guided by these texts.

Research Methods

I conducted this research in Tucson, a city of 520,000 people in Southern Arizona, 60 miles north of the US-Mexico border and 120 miles south of Phoenix, the state capital of Arizona. In 2002, the last year in which a community survey was conducted, Tucson had a Jewish population of approximately 22,300 (Sheskin 2003). In comparison with similar communities, Tucson’s Jewish population has the highest percentage of Jews who identify as being “just Jewish”—one of the lowest levels of religious practice, ritual observance, and Jewish organizational affiliation, and the lowest percentage of overall involvement and sense of Jewish “belonging.”

This project included 35 in-depth ethnographic interviews; two years of participant-observation; and the gathering of references to Judaism, healing, and prayer in rabbinic and popular books, newspapers, blogs, and online forums. As an anthropologist, I seek to situate the practices I study within the broader lifeworlds of my informants, so I could not separate the Mi Sheberach from the rich and complicated communal and ritual life in which it is embedded. Interviews about the Mi Sheberach therefore included long discussions about Judaism and Jewish identity, and an essential part of the project was participant-observation in synagogues, Jewish communal and educational events, and healing-related events.

I conducted interviews with rabbis, cantors, hospital chaplains, people who were ill and people who have said the Mi Sheberach for their friends and families. These included people affiliated with Reform or Conservative synagogues, unaffiliated Jews, and Jews whose connections to the community were primarily social and/or cultural. Most were in their 50s and 60s, retired or semi-retired, many from careers in the health professions. The interviews were semistructured and informal, and each lasted from one to three hours. Participants were encouraged to tell their stories in their own ways, and to create narratives that were personally meaningful to them. I recorded most of the interviews digitally and transcribed them. During some of the interviews, when recording was not appropriate or possible, I took detailed notes and wrote summaries after the interviews. I then coded transcripts and notes for common themes,Footnote 1 using an iterative, grounded-theory approach.

Participants’ stories of prayer and healing varied greatly, and they included a number of situations: a woman who chanted the Mi Sheberach to her father as he lay dying in a hospice; several people whose preoperative checklists before surgery included making sure that they were on their congregation’s Mi Sheberach list; a couple who played the Mi Sheberach every night for their comatose son; a cancer patient who described himself as a secular, “cultural Jew,” but who said, “Everyone’s praying for me, the Jews, the Catholics, the Buddhists… I’ll take it all”; and the many people who, finding that a friend or family member was ill, said simply: “I’ll say a Mi Sheberach for you.”

I recruited study participants from Reform and Conservative synagogues, at a support group for Jewish women with cancer, through an ad placed in the local Jewish newspaper, and through referrals from rabbis and other study participants. These recruitment strategies meant that all participants were in some way connected to the organized Jewish community or to a Jewish organization, but there was tremendous diversity in how this connection manifested itself and what it meant. According to the 2002 Tucson Jewish Community Study (Sheskin 2003), Tucson’s Jewish population self-identifies as 2% Orthodox; 21% Conservative, 32% Reform, and 44% “just Jewish.” Initially, I attempted to mirror these proportions in my sample. However, it quickly became clear that these categories did not fit the narratives people told me about their Jewish lives. Many people had multiple affiliations and combined practices that might link them with several of these denominations. In many ways, both the interview participants and the larger Tucson Jewish community in which this study took place are examples of what Horowitz (2000) calls a “mixed pattern of Jewish engagement.” She writes that they are characterized by:

…a more circumscribed Jewish involvement along with integration and high achievement in the American mainstream. The people who have mixed patterns of Jewish engagement are not indifferent about being Jewish, but their ongoing Jewish involvement depends on it being both meaningful and fitting in with their lives. The people who subscribe to this …form of Jewishness experience their Judaism as a set of values and historical people-consciousness rather than as a mode of observance (Horowitz 2000: v).

Praying for Healing and Finding Connection, Comfort, and Strength

For most of these people, their participation in this study was the first time they had attempted to articulate their hopes and expectations from their prayer practices. When I asked what they expected when they prayed for someone else’s healing, they often paused for a long time before answering. They didn’t know at first, and they found the question difficult to answer. After much thought, one woman told me, “When I say the Mi Sheberach, I don’t expect anything at all.” The most common answer I received was that reciting the prayer couldn’t hurt and it might even help. As a hospital chaplain told me:

[Most people today] are very scientific, intellectually skeptical, questioning… but they are moved to tears when I say the Mi Sheberach with them. There’s a big difference between what we hold intellectually and how we respond to life and death emotionally.

Often, these emotional reactions are hard to articulate. They are embodied and sensory, rather than cognitive, which can make them hard to study. The research data I collected is full of complexity and contradiction, because it represents the experiences and perspectives of my informants, and being human and Jewish in the modern world is often complicated, confusing, and contradictory. Despite the participants’ difficulty in verbally describing their experiences, it became clear that praying for healing had multiple impacts on them. In the sections that follow, I will describe the most common of these: feeling connected, finding comfort, experiencing a sense of agency, and creating and reinforcing identities.

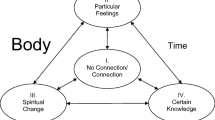

Connections

The most frequent theme to emerge from the data was that of connection(s). Modern American society emphasizes independence. This can leave people feeling isolated, particularly at a time of illness. When I asked people how the Mi Sheberach makes them feel, they almost always began with the word: “connected.” People are connecting to many different things: to each other as individuals; to community; to traditions and ancestors; to God, which may mean many different things to the respondents; to dormant parts of themselves; or, to some part of the experience of illness of which they were not previously aware.

These connections may be very practical. When someone stands up and says the name of an ill person, this notifies the rabbi and other members of the community that someone may need their support. Several rabbis commented that the Mi Sheberach helps them to know what is happening in the community. Many times, I have seen people register a name as it is being said, and then approach the person who said it after services, asking about the person and the person’s needs. One of my interviewees, a man who had not discussed his cancer publicly, but who was not keeping it a secret either, received a note from his family’s dentist: “I saw your name on the Mi Sheberach list. I hope all is well.” While the recitation of the traditional Mi Sheberach represented the family’s wishes for healing, it soon helped to mobilize friends and community in support of the ill person.

Depending on the nature of the illness, this added communal dimension could also present complications. One woman told me that when she was going through a difficult emotional period, she asked the rabbi to put her on the list, but to use her Hebrew name so that no one would recognize her. Another woman had the opposite reaction when dealing with a stigmatized illness. When she entered in-patient treatment for an addiction to pain killers, she told the rabbi this: “Put me on the list, and tell everyone why. They need to know that this happens in our community.” Greg,Footnote 2 who frequently attends services at both a small Reform congregation and a local Chabad center, found that the Mi Sheberach helped him to make peace with his complex emotions about his ex-wife’s mental illness. He also felt strongly that his friends would not understand this. He evoked her name during the Mi Sheberach each week, but he did so silently, so that he would not have to explain. This is what he told me:

I’m praying for my children’s mother to get well. I think I would be sinning if I didn’t try to help her. I believe in Hashem, I have to do this. All of the legal obligations of the divorce feel like being forced to stay connected to someone who is so sick. But the Mi Sheberach is one way that I can stay connected through love, not illness.

These emotional experiences of connection were common among those I interviewed. At a time when illness had cut them off from other people, the Mi Sheberach made them feel less isolated. David, a member of a Conservative synagogue, made this comment:

I was sick for a really long time. I was alone a lot. But when I knew that people at shul were praying for me, I didn’t feel so alone… I mean, I was alone, no one could really understand what I was going through, but I wasn’t really alone with it.

Shira, who was going through cancer treatment, could not put into words the feeling this evoked. She cried as she simply told me this: “They were thinking of me… they were thinking of me….”

For those saying the prayer, the feeling of connection was powerful. Melissa described the Mi Sheberach as her favorite part of the Friday night service at her Reform congregation:

I don’t know if it makes a difference, out in the world, but I know that it makes a difference in my relationship to them. I feel more connected to the people I pray for, even if they don’t know I did it.

It is important to note that the Mi Sheberach does not stand alone in building these connections. Laurel, who had experienced multiple illnesses over the past ten years, and who had been on the Mi Sheberach list at her synagogue several times, gave this explanation:

The first time I asked to be on the list, I thought I was going to die, and I needed someone to recognize that I was also a spiritual person. But it didn’t mean the same thing as the other times. The other times, we had already been involved for years. We had been on all these committees together; they brought me food; they stayed with me when I couldn’t be alone. We were connected in so many different ways.

Of course, there is a preexisting communal context to the phenomenon of connection that I am describing: You cannot be on the Mi Sheberach list unless you are already in some way connected to other people in the community. Someone needs to know that you are sick in order to add your name.

Comfort and strength

The second most frequent theme to emerge from the data was comfort. People could rarely provide me with more details about what that comfort felt like or meant to them. Sometimes they reverted to metaphor. One described the Mi Sheberach as “like matzah-ball soup for your spirit.” Often, the answer involved physical gesturing and sighs: “It’s like… oh… um… it just felt good here,” one participant said with a smile, pointing to mid-torso.

Those who could put these embodied experiences into words identified a number of emotional benefits. Reciting the Mi Sheberach provided some sort of emotional relief, often expressed as “acceptance,” they said, both for those saying it, and for those for whom it is said. A man described standing up to say his father’s name, and then realizing, “It was a public acknowledgement that someone I care about was very sick.”A number of people noted that saying the Mi Sheberach out loud in this way gave them emotional strength during a particularly difficult period. Russell, who regularly said the Mi Sheberach for one of his closest friends who had been diagnosed with advanced cancer, described it this way:

When you say the Mi Sheberach, you come to it from that place of worry, anxiety, brokenheartedness. Then it does something, not physically, biologically… but maybe it does… but it gives you strength.

“Strength” means different things to different people. For some, it meant reinforcing the idea that they could cope with what was happening. For others, it was a reminder that they had made courageous choices for the sake of their health. A week before elective orthopedic surgery, Ann, an active member of two Reform congregations, made this comment:

I chose to have this surgery. It seems like a brave thing to do but I have a lot of fear around it. When I think about Debbie Friedman’s words, “Help us find the courage to make our lives a blessing,” that’s so meaningful for me right now. Being blessed with courage… so powerful.

And for some, the Mi Sheberach reduced the stresses and fears associated with serious illness. Miriam reflected back on her thoughts before a complicated surgical procedure:

I really thought I was going to die. I was terrified going into the surgery. But the rabbi came and we sang the Mi Sheberach over and over, and I knew that the congregation was saying it for me, too, that my friends and community were thinking of me. And somehow by the time they wheeled me into the OR, I was calm. I was OK. I don’t know what happened, but I was so grateful for it.

Agency

Social scientists have long studied agency—the ability of individuals and groups to contest, resist, and negotiate with cultural norms and expectations. It is clear from these interviews that prayer serves as a conduit for agency in a time and place characterized by increasing biomedicalization and technoscientific innovations (Clarke et al. 2010). Despite the pervasiveness of biomedical authority, many people in the study commented on the mysteries of health and illness. They noted that prayer gave them a sense of control at a time of perceived vulnerability and helplessness. They recognized that modern medicine was not always predictable, and prayer reminded them to be, as one said, “open to the miracles and possibilities.” A cantor explained to me that the Talmud teaches that visiting the sick relieves one-sixtieth of their illness. No one treatment can work by itself, he said:

When we say the Mi Sheberach, it’s like we’re saying: God will help, we will help, use all the medicines you can. It’s not instead of. It’s in addition to. You don’t know what’s going to work.

Ram, who was halfway through a long and complicated treatment protocol when we met, echoed this sentiment:

Being sick, I felt completely powerless—over my life, over my health, over my future. We’re completely dependent on the medical community to fix us. But this was something I could do. Knowing that I was on the Mi Sheberach list reminded me to stay open to healing.

This feeling of helplessness extends to those who care about, and care for, the sick. Some of my interviewees felt strongly that the Mi Sheberach was equally, or maybe even more important for the person saying it than for the ill person. One woman told me this explicitly: “I say it for me, not for them. I don’t think it helps them at all. But it helps me…”

Rachel explained this same feeling in more detail:

People feel so disconnected, so helpless, when someone they love is sick and they don’t know what to do. There really isn’t anything we can do. But putting someone’s name on the list, or standing up and saying the name out loud at services, being part of the congregation when we all sing it together, it makes us feel like we’ve done something, that we’ve helped the person in some way.

Identity

The participants in this study live their Judaism in ways that cannot be easily categorized. Their Jewish identities ebb and flow across the life cycle; they take on, reject, reinvent, and/or combine Jewish practices with other practices in their search for personal meaning; they struggle with belief and move between communal affiliations and allegiances over time and place. Within this context, times of illness or loss become sites of negotiation, through which their relationships to Jewish traditions, practices, and communities shift and become transformed.

Saying the Mi Sheberach connects people to their Judaism in new ways, although, interestingly, very few of my interviewees used the word “Judaism” to describe this. Many of them talked about feeling connected to “tradition” or “ancestors” at a time when they would otherwise feel lost. They described this as something deep inside stirring to life. One culturally Jewish woman at the support group said that the Mi Sheberach resonated with her “Jewish genes.” Another woman used the Yiddish word for “soul” to describe the Jewish part of her that felt comforted: “It touched me in my n’shama.” A hospital chaplain explained to me why he thinks the Mi Sheberach resonates so much with people in the hospital:

It’s something familiar at a time when everything is strange. It connects us to our lineage, our heritage, our tradition. There’s something very comforting in that. People have a sense that this is what Jews do.

Often, the people I was interviewing knew only the modern version of the prayer, yet its historical resonance was still central to their reactions to it. Sarah, who had said the Mi Sheberach for her ill adult son told me: “It’s so powerful knowing that people have been saying these exact words for thousands of years.” When I pointed out that the version she was referring to was only 20 years old, she was baffled. Others noted that the prayer, whether the traditional or modern version, invokes “God who blessed our ancestors,” reminding them that they were not the first (nor will they be the last) to struggle with illness and life challenges.

For some, their experiences with the Mi Sheberach catalyzed a new appreciation for the power of prayer and other Jewish rituals. Lisa, who sang the Mi Sheberach repeatedly to her dying mother, expressed this reflection:

Before, it was just a song. I went to services, I sang the prayers, I was Jewish. I liked being Jewish, but it was intellectual. Now there’s a spiritual thing that happens. Now it makes the service holy.

Another woman was so moved by the congregation’s ongoing offering of prayers during a long illness that, when she finally felt well again, she began attending services regularly and participating in weekly study groups and community social events.

Physical Healing

It is important to acknowledge that a small number of people attributed physical improvements to the prayers that were said for them. Friends and family from diverse religious and spiritual traditions had prayed for these people, and they felt that the accumulated effect of these prayers had changed the physical outcome of their illness. Sima, suffering from congestive heart failure, said this: “There is no medical reason why I am doing as well as I am. I shouldn’t be alive. My cardiologist can’t explain it at all.” She attributed it to the “river of love” that came her way during the worst of her illness. Joseph was amazed that his wife did not need the second round of cancer treatment that her doctors had originally prescribed. He attributed this to the fact that people all over the world were saying the Mi Sheberach for her. Interestingly, his wife credited the newer chemotherapy drugs for her improvement.

Concluding Thoughts

An anthropological approach to healing recognizes that healing is a multifaceted process, embedded in cultural values and social institutions (Kirmayer 2011). Healing may be physical, emotional, social, and theological; it may include “the ritual reframing of reality and the consequent personal and cosmological transformations” (Roseman 1988: 814). All forms of healing—including the biomedical, the traditional, the psychotherapeutic and the religious—are moral practices, based in what is at stake in local worlds, and embedded in the varieties of lived experience (Kleinman and Seeman 1998).

In 21st-century America, what is at stake for the Jewish community is the meaning of being Jewish and the relationship of individual Jews to the collective. In the last several decades, there has been a shift “away from a focus on the collective, historical experience of the Jewish people and toward a highly individualized appropriation of Jewish symbols, beliefs, and practices as part of the search for personal meaning” (Woocher 2005: 287). Much like American religion, in general, (Putnam and Campbell 2010; Roof 1999; Wuthnow 1998), Judaism in America is increasingly a matter of choice, based in an individual interpretation of what is meaningful and practical for each person’s life (Kaplan 2005; Liebman 2005). The participants in this study are very much liberal American Jews of the 21st century—“sovereign Jewish selves” (Cohen and Eisen 2000) engaged in lifelong “Jewish journeys” (Horowitz 2000). Within this context, the Mi Sheberach and other healing prayers and activities become one site, among many, through which relationships to Judaism and to the Jewish community are negotiated and constructed. The participants in this study choose, and maintain, those Jewish practices, like the Mi Sheberach, that resonate emotionally and/or spiritually and that fit within the larger context of their lifeworlds—in this case, the search for meaning, comfort, strength, and connection during times of illness and healing.

Yet this individualism is also inherently communal. While individuals choose practices that resonate personally, an essential part of this resonance is the experience of community, connection, and tradition. The individual’s search for meaning is synthesized with the collectivist nature of Judaism, in which religious behavior, identity, and ritual are socially motivated, encouraging social integration and promoting a sense of community (Cohen et al. 2005). As both McGinity (2009) and Thompson (2013) have shown, individual expressions of Jewish agency are often rooted within a communal and historical context—a deep sense of inherited peoplehood, and the collective experience of ritual, history, text, and tradition. Modern American Jews weave together individualism and tradition, using involvement in Jewish institutions to connect their individual “sovereign selves” with the larger Jewish community. In the case of the Mi Sheberach, ritual serves as this connective link, creating opportunities “for reflexivity, for contemplating and constructing a self integrated with cultural norms” (Prell-Foldes 1980:81). Healing occurs as people find new connections to themselves and each other through these reflexive acts of meaning-making; at the same time, the use of Hebrew, being with other Jews in a synagogue setting, and using a prayer from the traditional liturgy (whether modified or not) catalyzes a reconnection to a Judaism that feels both personally and traditionally authentic (Rothenberg 2006; Sered 2005).

Individual meaning-making and collective experience are inextricably intertwined, in a pattern that reflects both the nature of Jewish communities and ongoing American negotiations between individuation and social cohesion (Bellah et al. 1985). This is far from a simple process, and it is a source of both tension and innovation. Modern American Jews are engaged in an ongoing and continually evolving process of interpretive interaction among text, tradition, and personal experience. For the participants in this study, prayers for healing are an inherently social process, inextricably linked to relationships with other people, to the community, to God, and to tradition. Prayer means something different to each of the participants in this study, yet, for all, it is embedded in history and text, and it leads to the creation of social and interpretative communities.

Notes

It is important to note that, while common themes emerged clearly from the data, there was also much contradiction. Often, a single individual expressed opposing viewpoints and understandings. This is not surprising, given that the project explores the dissonances and multiplicities of practice and identity. Each individual’s journey and meaning-making were personal and unique. Despite this, it was striking how often the participants used similar words and concepts to describe these experiences.

All names are pseudonyms.

References

Asad, Talal. 1993. Genealogies of religion: Discipline and reasons of power in Christianity and Islam. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Barnes, Linda L. 2011. New geographies of religion and healing: States of the field. Practical Matters 4: 1–82.

Barnes, Linda L., and Susan S. Sered (eds.). 2005. Religion and healing in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bellah, Robert N., Richard Madsen, William M. Sullivan, Ann Swidler, and Steven M. Tipton. 1985. Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Boyarin, Jonathan. 2011. Mornings at the Stanton Street Shul: A summer on the Lower East Side. New York: Fordham University Press.

Brink-Danan, Marcy. 2008. Anthropological perspectives on Judaism: A comparative review. Religion Compass 2(4): 674–688.

Brink-Danan, Marcy. 2012. Jewish life in 21st-century Turkey: The other side of tolerance. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Buckser, Andrew. 2003. After the rescue: Jewish identity and community in contemporary Denmark. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bunin Benor, Sarah. 2012. Becoming frum: How newcomers learn the language and culture of Orthodox Judaism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Charmé, Stuart, Bethamie Horowitz, Tali Hyman, and Jeffrey S. Kress. 2008. Jewish identities in action: An exploration of models, metaphors and methods. Journal of Jewish Education 74(2): 115–143.

Charmé, Stuart, and Tali Zelkowicz. 2011. Jewish identities: Educating for multiple and moving targets. In International handbook of Jewish education, ed. H.E.A. Miller. Dordrecht: Springer.

Clarke, Adele E., Janet K. Shim, Laura Mamo, Jennifer Ruth Fosket, and Jennifer R. Fishman. 2010. Biomedicalization: Atheoretical and substantive introduction. In Biomedicalization: Technoscience, health, and illness in the US, ed. Adele E. Clarke, Laura Mamo, Jennifer Ruth Fosket, Jennifer R. Fishman, and Janet K. Shim, 1–44. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Cohen, Adam B., Daniel E. Hall, Harold G. Koenig, and Keith G. Meador. 2005. Social versus individual motivation: Implications for normative definitions of religious orientation. Personality and Social Psychology Review 9(1): 48–61.

Cohen, Steven M, and Arnold M. Eisen. 2000. The Jew within: Self, family and community in America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Cowan, Rachel. 1997. Yom Kippur 1996. In Beginning anew: A woman’s companion to the High Holy Days, ed. Gail Twersky Reimer, and Judith A. Kates, 276–282. New York: Touchstone.

Cutter, William. 2011a. A prayer for healing: The Misheberach. Sh’ma 41(681): 4–5.

Cutter, William (ed.). 2007. Healing and the Jewish imagination. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing.

Cutter, William (ed.). 2011b. Midrash and medicine: Healing body and soul in the Jewish interpretive tradition. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing.

Davidman, Lynn. 2007. The new voluntarism and the case of the unsynagogued Jews. In Everyday religion: Observing modern religious lives, ed. Nancy T. Ammerman, 51–67. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Fader, Ayala. 2009. Mitzvah girls: Bringing up the next generation of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Freeman, David L., and Judith Z. Abrams (eds.). 1999. Illness and health in the Jewish tradition: Writings from the Bible to today. Philadelphia, PA: The Jewish Publication Society.

Heilman, Samuel C. 2000. Ethnography and biography, or what happened when I asked people to tell me the story of their lives as Jews. Contemporary Jewry 21(1): 23–32.

Horowitz, Bethamie. 2000. Connections and journeys: Assessing critical opportunities for enhancing Jewish identity. New York: UJA - Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York.

Horowitz, Bethamie. 2002. Reframing the study of contemporary American Jewish identity. Contemporary Jewry 23(1): 14–34.

Hyman, Tali. 2004. At home with many identities. Sh’ma, 10–11.

Kahn, Susan Martha. 2000. Reproducing Jews: A cultural account of assisted conception in Israel. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kaplan, Dana Evan. 2005. Introduction. In The Cambridge companion to American Judaism, ed. Dana Evan Kaplan, 1–19. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kelman, Ari Y. 2012. The end of identity? Contemporary Jewry 32: 209–211.

Kirmayer, Lawrence J. 2011. Unpacking the placebo response: Insights from ethnographic studies of healing. The Journal of Mind-Body Regulation 1(3): 112–124.

Klassen, Pamala E. 2011. Spirits of protestantism: Medicine, healing and liberal Christianity. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kleinman, Arthur, and Don Seeman. 1998. The politics of moral practice in psychotherapy and religious healing. Contributions to Indian Sociology 32(2): 237–252.

Krasner, Jonathan. 2014, May 29, 2014. The persistence of “identity.” Learning about Learning. Retrieved from blogs.brandeis.edu/mandeljewished/?p=1746.

Kugelmass, Jack (ed.). 1988. Between two worlds: Ethnographic essays on American Jewry. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Levin, Jeff, and Prince, Michelle F. 2010. Judaism and health: Reflections on an emerging scholarly field. Journal of Religion and Health 50(4): 765–777.

Liebman, Charles S. 2005. The essence of American Judaism. In The Cambridge companion to American Judaism, ed. Dana Evan Kaplan, 133–144. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1981. After virtue: A study in moral theory. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

McGinity, Keren R. 2009. Still Jewish: A history of women and intermarriage in America. New York, NY: New York University Press.

McGuire, Meredith B. 1988. Ritual healing in suburban America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Mehta, Samira K. 2015. Chrismukkah: Millennial multiculturalism. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 25(1): 82–109.

Neriya-Ben Shahar, R. 2015. “At ‘amenmeals’ it’s me and God”. Religion and gender: A new Jewish women’s ritual. Contemporary Jewry 35(2): 153–172.

Orsi, Robert A. 2002. The Madonna of 115th Street: Faith and community in Italian Harlem, 1880–1950, 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pelc Adler, Julie. 2011. A Midrash on the Mi Sheberakh: A prayer for persisting. In Midrash and medicine: Healing body and soul in the Jewish interpretive tradition, ed. R. William Cutter, 277–280. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing.

Person, Hara E. (ed.). 2003. The mitzvah of healing: An anthology of essays, Jewish texts, personal stories, meditations, and rituals. New York, NY: Women of Reform Judaism/UAHC Press.

Prell, Riv-Ellen. 1989. Prayer and community: The Havurah in American Judaism. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Prell, Riv-Ellen. 2000. Developmental Judaism: Challenging the study of American Jewish identity in the social sciences. Contemporary Jewry 21(1): 33–54.

Prell-Foldes, Riv-Ellen. 1980. The reinvention of reflexivity in Jewish prayer: The self and the community in modernity. Semiotica 30(1/2): 73–96.

Putnam, Robert D., and David E. Campbell. 2010. American grace: How religion divides and unites us. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Roof, Wade Clark. 1999. Spiritual marketplace: Baby boomers and the remaking of American religion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Roseman, Marina. 1988. The pragmatics of aesthetics: The performance of healing among Senoi Temiar. Social Science and Medicine 27(8): 811–818.

Rosman, Steven M. 1997. Jewish healing wisdom. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson Inc.

Rothenberg, Celia E. 2006. Hebrew healing: Jewish authenticity and religious healing in Canada. Journal of Contemporary Religion 21(2): 163–182.

Seeman, Don. 2009. One people, one blood: Ethiopian-Israelis and the return to Judaism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Sered, Susan S. 2005. Healing as resistance: Reflections upon new forms of American Jewish healing. In Religion and healing in America, ed. Linda L. Barnes, and Susan S. Sered, 231–252. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sheskin, Ira M. 2003. The 2002 Tucson Jewish Community Study: Summary report. Tucson, AZ: Jewish Federation of Southern Arizona.

Silverman, Gila S., Johnson, Kathryn A., and Cohen, Adam B. 2016. To believe or not to believe, that is not the question: The complexity of Jewish beliefs about God. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality.

Thompson, Jennifer A. 2013. Jewish on their own terms: How intermarried couples are changing American Judaism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Weintraub, Simkha Y. 1994. Healing of soul, healing of body: Spiritual leaders unfold the strength and solace of the Psalms. Woodstock, VT: Jewish Lights Publishing.

Weiss, Eric (ed.). 2013. Mishkan R’fuah: Where healing resides. Central Conference of American Rabbis, New York.

Woocher, Jonathan. 2005. “Sacred survival” revisited: American Jewish civil religion in the new millennium. In The Cambridge companion to American Judaism, ed. D.E. Kaplan, 283–298. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wuthnow, Robert. 1998. After heaven: Spirituality in America since the 1950s. Berkely, CA: University of California Press.

Zelkowicz, Tali E. 2013. Beyond a Humpty–Dumpty narrative: In search of new rhymes and reasons in the research of contemporary American Jewish identity formation. International Journal of Jewish Education Research 5–6: 21–46.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this research were funded by the School of Anthropology, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Research Institute, both at the University of Arizona. I am grateful to Mark Nichter, Jeff Levin and David Graizbord, who provided invaluable feedback on earlier versions of this article. I also thank the anonymous reviewers, for their very helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Silverman, G. “I’ll Say a Mi Sheberach for You”: Prayer, Healing and Identity Among Liberal American Jews. Cont Jewry 36, 169–185 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-016-9156-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-016-9156-7