Abstract

Background

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether patients receiving a stress echocardiogram or myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) test have differences in subsequent testing and outcomes according to accreditation status of the original testing facility.

Methods and results

An all-payer claims dataset from Maine Health Data Organization from 2012 to 2014 was utilized to define two cohorts defined by an initial stress echocardiogram or MPI test. The accreditation status (Intersocietal Accreditation Commission (IAC), American College of Radiology (ACR) or none) of the facility performing the index test was known. Descriptive statistics and multivariate regression were used to examine differences in subsequent diagnostic testing and cardiac outcomes.

We observed 4603 index stress echocardiograms and 8449 MPI tests. Multivariate models showed higher odds of subsequent MPI testing and hospitalization for angina if the index test was performed at a non-accredited facility in both the stress echocardiogram cohort and the MPI cohort. We also observed higher odds of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) performed (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.13-2.50), if the initial MPI test was done in a non-accredited facility.

Conclusion

Cardiac testing completed in non-accredited facilities were associated with higher odds of subsequent MPI testing, hospitalization for angina, and PCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Accreditation is a process carried out by a recognized independent organization whereby institution and/or laboratories have an opportunity to demonstrate competency, commitment to standardization protocols with self-assessment tools including quality control and quality improvement, and maintaining accountability.1,2 Retrospective cohort studies have demonstrated the value of accreditation with regards to clinical care and practice outcomes in the field of cardiology, vascular surgery, trauma, and infectious disease.3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11

Brown et al demonstrated that accreditation of vascular laboratories was associated with more accurate characterization of carotid artery stenosis. However, this did not affect the clinical outcomes of patients who then underwent carotid artery endarterectomy.3 Similarly, in the field of cardiac echocardiography, Thaden et al demonstrated that accredited facilities were more likely to have completed clinical reports including documentation of left and right ventricular size, higher quality images, and diagnostic color and spectral Doppler imaging.12 Surveys and cohort studies further showed that the facility accreditation resulted in improvement in quality metrics, overall operations, diagnostic study quality and reporting.3,13,14,15,16 Nevertheless, accreditation status of facilities performing cardiovascular testing remains variable.17,18 Knowledge gaps include the relationships between accreditation status, utilization of diagnostic testing and resources as well as clinical outcomes.

The purpose of the study was to investigate the hypothesis that patients receiving cardiac testing at non-accredited facilities (compared to accredited facilities) experience additional testing and have less favorable clinical outcomes.

Methods

This is an observational analysis based on an all-payer medical claims dataset (APCD) from 2012 to 2014, the most recent data available at the time of this analysis, which includes insurance claims and eligibility information for nearly all beneficiaries in Maine insured by Medicare, Medicaid, or commercial insurers. The Maine APCD does not include claims paid by the Veterans Administration (VA) healthcare system. However, VA claims paid for by a separate commercial insurer would be included. The Maine APCD represents 90% of all Maine’s insured population with greater than $2,000,000 of adjusted premiums or claims processed per calendar year. All calculations and analyses were completed using SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1, Cary, N.C.

Cohort Development

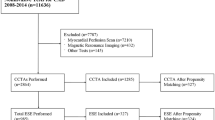

From the Maine APCD, we identified patients who were aged 35 and older, because we were primarily concerned with atherosclerotic heart disease. Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used to identify all stress echocardiograms and MPI in the data. The claims were de-duplicated into distinct events by counting only one procedure per person per day. The index event refers to the first time we observed either a stress echocardiogram or MPI in 2013. Patients were required to have continuous health insurance coverage 12 months prior to and following their index event to capture new diagnostic processes for stable coronary artery disease and subsequent clinical outcomes. We assigned patients into two cohorts, based on whether the first test (“index test”) was a stress echocardiogram or MPI. Patients who received their index tests at low volume facilities (fewer than 10 tests in 2013) were excluded because of data reliability.

We then used a 12-month look-back to exclude people with underlying unstable coronary disease using International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), unstable angina, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). We also used the 12-month look-back to define comorbidities in prior claims. Figure 1 shows the development of the cohorts. Our final two cohorts included 4603 patients with an index stress echocardiogram and 8449 patients with an index MPI test.

Accreditation Type for Facility Performing the Index Test

The Intersocietal Accreditation Commission (IAC) provides laboratory accreditation in echocardiography and nuclear medicine, whereas the American College of Radiology (ACR) provides accreditation in the field of nuclear medicine.19,20 The IAC provided a table of accreditation status (IAC or ACR) in 2013 for accredited health care facilities in Maine. We categorized each index test according to whether the test was performed in a facility that was accredited by the IAC, the ACR, or neither the IAC nor the ACR (“non-accredited”). Of note, all inpatient hospital-based facilities were also accredited by Joint Commission. Stress echocardiograms were only evaluated as IAC accredited or not IAC accredited as there is no ACR accreditation for these procedures.

Of the total of 27 echocardiogram facilities across the state of Maine, 20 facilities were included in the stress echocardiogram cohort, the remaining were excluded due to low volume. Seven of the 20 facilities were IAC accredited. Similarly, of the total 38 MPI facilities, 37 laboratory facilities were included in the nuclear stress test cohort and 1 testing facility was excluded due to low volume. Of the 37 facilities, 4 facilities were accredited by the IAC accreditation and 7 facilities were the ACR accredited. We had 13 patients in the nuclear stress testing cohort who received their test at a VA medical center.

Subsequent Diagnostic Testing, Procedures and Cardiac Outcomes After Index Stress Echocardiogram or MPI

We used CPT and ICD-9 codes to identify patients in each cohort who received additional diagnostic testing within 6 months of the index test, including subsequent stress echocardiogram, subsequent MPI, other imaging category including full echocardiogram, cardiac nuclear medicine study besides MPI, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography angiography, and computed tomography coronary calcium score. We also identified clinical events such as cardiac catheterization, revascularization with either PCI or CABG, cardiac outcomes such as hospitalization for angina, hospitalization for unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, and heart failure.

Statistical Analysis

We compared baseline characteristics of the cohorts using Chi-square and t tests as appropriate, evaluating variables that may be confounders of relationships between accreditation type and cardiac outcomes. The covariates of interest included age, sex, previously diagnosed stable coronary artery disease, diabetes, other medical comorbidities as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index,21,22 and insurance type.

We then created separate regression models with accreditation status of facility as the predictor of interest (independent variable) and additional diagnostic testing by modality, revascularization and hospitalizations for specific cardiac events as the outcomes of interest (dependent variables) in separate models. All models were also adjusted for age, sex, insurance type (as of the month of the index test), diabetes, prior stable coronary artery disease (CAD) diagnosis, the Charlson comorbidity index,21,22 and institutional volume of procedures (dichotomized to < or ≥ 200 stress echocardiogram tests and < or ≥ 500 MPIs in the period of observation). These cutoffs were selected due to the natural distribution of the data.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the index stress echocardiography and MPI study populations according to facility accreditation status. We observed 4603 index stress echocardiograms and 8449 MPI tests. In the MPI cohort, the patients who received care in the IAC accredited facilities had significantly more stable coronary artery disease and more comorbidities when compared to non-accredited facilities or ACR accredited facilities.

Table 2 depicts subsequent diagnostic testing within six months of the index test in the stress echocardiogram cohort. Among the patients having the index test in a non-accredited facility a higher proportion had subsequent MPI tests after the index test, compared to those in the accredited facilities (3.5% vs 1.8%, p < .001). For patients in the MPI cohort (Table 3), we also observed a higher proportion of patients having subsequent MPI: .7% in non-accredited facilities compared with .4% in IAC facilities and none in ACR facilities (p < .01). Similarly, non-accredited facilities (12.9%) were more likely to undergo cardiac catheterization compared to 11.2% in IAC or 1.2% in ACR accredited facilities (p = .02). For both cohorts, we did not observe differences in subsequent stress echocardiography, or other imaging tests.

Table 4 shows the percentage of patients with specific cardiac outcomes within 6 months after the index tests, according to accreditation status. For the stress echocardiography cohort, there were fewer hospitalizations for angina (0.2% vs 0.6%, p = .04) and more hospitalization with AMI (1.6% vs 0.9%, p = .05) in patients having their index test at an IAC accredited facility. For the MPI cohort, we observed a higher proportion were hospitalized for AMI (IAC 3.3% vs ACR 2.3% vs 2.0%, p ≤ .001) and heart failure (IAC 15.2% vs ACR 8.9% vs 10.4%, p < .001) among those having their index test at an IAC accredited facility compared to ACR and non-accredited facilities. Among both stress echocardiography and MPI cohort, we did not observe significant differences in hospitalization for unstable angina, cardiac arrest, or death.

Multivariate models for index stress echocardiography cohort (Table 5) demonstrated higher odds of subsequent MPI testing for those who had an index test at non-accredited facilities compared with IAC accredited facilities (odds ratio (OR) 2.28, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.50-3.46) but no other significant testing differences were observed. Additionally, patients who had an index test at non-IAC accredited facilities had higher odds of hospitalization for angina compared with accredited facilities (OR 3.54, 95% CI 1.22-10.28).

Multivariate models for index MPI cohort are shown in Table 6. For those having an index MPI in non-accredited facilities, we observed higher odds of subsequent MPI, other imaging, cardiac catheterization, and PCI, and lower odds of subsequent stress echocardiogram compared with those having an index test at IAC accredited facilities. Patients treated at ACR accredited facilities were more likely than those treated at IAC accredited facilities to receive PCI. We also observed higher odds of hospitalization for angina in non-accredited facilities when compared to IAC accredited facilities (OR 1.97, 95% CI 1.13-3.44).

Discussion

In our study, we observed important differences in subsequent cardiac testing and clinical outcomes depending upon the accreditation status of the facility performing the initial (index) cardiac stress test. For patients undergoing an initial stress echocardiogram or MPI test at a non-accredited facility, we observed higher odds of subsequent MPI testing and hospitalization for angina in adjusted models, compared with those having initial testing in an accredited facility (Tables 2, 3, 4). Conversely, we observed higher rates of hospitalization for AMI in patients undergoing either stress echocardiogram or MPI test at an IAC-accredited facility, and higher rates of hospitalization for heart failure among IAC-accredited group in MPI cohort.

The sensitivity of the exercise or pharmacologic stress echocardiography ranges from 70 to 90%, whereas the sensitivity for MPI ranges from 88 to 91%.23 In the common scenario of a patient with recurrent anginal symptoms, repeat testing with a more sensitive modality might be pursued, including but not limited to anatomic assessment with CT coronary angiography. We postulate that despite normal index stress echocardiography or index MPI results, there may be continued suspicion for coronary artery disease or concerns for false negative results, and therefore more subsequent hospital admissions for angina along with repeat cardiac testing with a similar or more sensitivity modality. We postulate that other factors contributing to this discrepancy include concerns for limited or poor study quality and/or reporting, false negatives and/or ambiguous results of the initial testing requiring subsequent referral to dedicated centers whereby providers may want to repeat their own test.24,25,26,27,28

On the other hand, with lack of information about results of the cardiac stress test, it is challenging to explain the rationale behind high rates of AMI and hospitalization for heart failure. In 1996, Varga et al demonstrated that pharmacologic stress echocardiography inconsistently identified the site of future infarction.29 We hypothesize that factors contributing to an increased AMI rates and hospitalization for heart failure in an accredited facility may include a combination of factors such as complex patients with higher comorbidities, higher percentage of patients with prior known coronary artery disease (Table 1), higher level of vascular inflammation and/or altered composition of atheromatous plaque such as higher levels of macrophage with thin fibrous cap more prone to rupture and thrombotic occlusion.29,30,31

Prior studies have demonstrated the value of accreditation in various fields including cardiovascular disease, infectious disease, and pain management with regarding to clinical outcomes and quality of healthcare delivery.11 As cardiovascular disease continues to be the foremost cause of mortality and morbidity in the USA, there has been a rapid progression in the types of imaging modalities and volume of tests performed for assessment of coronary artery disease over the last two decades.32 Observational studies and surveys have further demonstrated the benefit of accreditation of noninvasive cardiac imaging laboratories with regards to study quality and standardization of reporting.3,12,13,14,15,18 However, previously there has been a lack of data connecting impact of accreditation of facilities performing diagnostic cardiac testing to patient centered clinical outcomes.

This study had several limitations. Our data were derived from medical claims, and we had relatively limited information about clinical characteristics of the patients. There is lack of information with regards to appropriateness of diagnostic test being ordered, diagnostic testing test quality, and we were unable to review actual test reports. Appropriate use criteria (AUC) for echocardiography and nuclear stress testing indicate that repeat stress testing post revascularization is appropriate for ischemia evaluation in symptomatic patients, however, it would be inappropriate to repeat stress testing in less than 2 years post percutaneous coronary intervention in an asymptomatic patient.33,34,35 Additionally, nuclear stress testing AUC further states that if the index stress testing is normal, it is uncertain or inappropriate if repeat testing is performed in less than 2 years.35 Our study was thereby designed to excluded patients who had ACS presentation, or underwent revascularization with CABG and/or PCI to limit confounding. Furthermore, we had limited statistical power to examine some outcomes that occur less commonly, such as CABG. In our study, we could only ascertain inpatient deaths as indicated in the claims.

Our data are limited to the State of Maine. Maine is one of the most rural states in the USA.36,37 Over the 2012-2014, the rate of uninsured people in the state of Maine was roughly 10-11%, compared to the national average of 16-17%.38 In our study, 20% of the patients were excluded in the stress echocardiogram cohort and 17% of the patients were excluded in the MPI cohort due to lack of continuous insurance coverage over the 2012-2014. Rural counties tend to have older population, higher poverty, lower median income, fewer healthcare providers per population as well as more limited access to healthcare facilities.39 All these factors may further impact provider and patient preference for a test being formed at a local facility, which may be less likely to be accredited due to a relatively low volume of tests performed.

Conclusion

This population-based observational study uniquely highlights some of the downstream effects of the accreditation process when it comes to patient care and outcomes. Effects of additional cardiac testing include potential delay in initial diagnosis and management, increased exposure to radiation, and overall higher healthcare delivery costs. We theorize this is primarily a quality issue with implications for patient outcomes and cost of care related to waste from potentially unnecessary repeat testing. However, additional studies are warranted to examine whether specific elements of the accreditation process are associated with higher quality cardiac imaging with reporting and subsequently impacting patient outcomes.

New Knowledge Gained

Accreditation status may play a role in reduced subsequent MPI testing within 6 months and hospitalization event for angina after an index echocardiogram or MPI stress test.

Abbreviations

- MPI:

-

Myocardial perfusion imaging

- IAC:

-

Intersocietal Accreditation Commission

- ACR:

-

American College of Radiology

- CAD:

-

Coronary artery disease

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary interventions

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- CPT:

-

Current Procedural Terminology

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

References

Echocardiography What is IAC Accreditation? https://www.intersocietal.org/echo/main/what_is_accreditation.htm.

Nuclear Medicine & PET Accreditation Program FAQ. https://www.acraccreditation.org/How-To/NucMed-PET-Accreditation-FAQ.

Brown OW, Bendick PJ, Bove PG, Long GW, Cornelius P, Zelenock GB, et al Reliability of extracranial carotid artery duplex ultrasound scanning: Value of vascular laboratory accreditation. J Vasc Surg 2004;39:366–71 discussion 71.

Chandra A, Glickman SW, Ou FS, Peacock WF, McCord JK, Cairns CB, et al An analysis of the Association of Society of Chest Pain Centers Accreditation to American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction guideline adherence. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:17–25.

Chen J, Rathore SS, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. JCAHO accreditation and quality of care for acute myocardial infarction. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22:243–54.

Menachemi N, Chukmaitov A, Brown LS, Saunders C, Brooks RG. Quality of care in accredited and nonaccredited ambulatory surgical centers. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:546–51.

Oh HS, Chung HW, Kim JS, Cho SI. National survey of the status of infection surveillance and control programs in acute care hospitals with more than 300 beds in the Republic of Korea. Am J Infect Control 2006;34:223–33.

Pasquale MD, Peitzman AB, Bednarski J, Wasser TE. Outcome analysis of Pennsylvania trauma centers: Factors predictive of nonsurvival in seriously injured patients. J Trauma 2001;50:465–72 discussion 73–74.

Ross MA, Amsterdam E, Peacock WF, Graff L, Fesmire F, Garvey JL, et al Chest pain center accreditation is associated with better performance of centers for Medicare and Medicaid services core measures for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2008;102:120–4.

Simons R, Kasic S, Kirkpatrick A, Vertesi L, Phang T, Appleton L. Relative importance of designation and accreditation of trauma centers during evolution of a regional trauma system. J Trauma 2002;52:827–33 discussion 33–34.

Alkhenizan A, Shaw C. Impact of accreditation on the quality of healthcare services: A systematic review of the literature. Ann Saudi Med 2011;31:407–16.

Thaden JJ, Tsang MY, Ayoub C, Padang R, Nkomo VT, Tucker SF, et al Association between echocardiography laboratory accreditation and the quality of imaging and reporting for valvular heart disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10(8):e006140.

Lopez L, Farrell MB, Choi JY, Cockroft KM, Gornik HL, Heller GV, et al Accreditation is perceived to improve echocardiography laboratory quality: Results of an intersocietal accreditation commission survey. J Diag Med Sonogr. 2017;33:163–71.

Manning WJ, Farrell MB, Bezold LI, Choi JY, Cockroft KM, Gornik HL, et al How do noninvasive imaging facilities perceive the accreditation process? Results of an intersocietal accreditation commission survey. Clin Cardiol 2015;38:401–6.

Bremer ML. Relationship of sonographer credentialing to intersocietal accreditation commission echocardiography case study image quality. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:43–8.

Behera SK, Smith SN, Tacy TA. Impact of accreditation on quality in echocardiograms: A quantitative approach. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2017;30:913–22.

Brown SC, Wang K, Dong C, Farrell MB, Heller GV, Gornik HL, et al Intersocietal accreditation commission accreditation status of outpatient cerebrovascular testing facilities among medicare beneficiaries: The VALUE study. J Ultrasound Med 2016;35:1957–65.

Brown SC, Wang K, Dong C, Yi L, Marinovic Gutierrez C, Di Tullio MR, et al Accreditation status and geographic location of outpatient echocardiographic testing facilities among medicare beneficiaries: The VALUE-ECHO study. J Ultrasound Med 2018;37:397–402.

About IAC Echocardiography Accreditation. https://www.intersocietal.org/echo/main/about_iac_echo.htm.

Nuclear Medicine ACR. https://www.acraccreditation.org/Modalities/Nuclear-Medicine-and-PET.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83.

Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613–9.

Task Force M, Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, et al 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: The Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003.

Knuuti J, Ballo H, Juarez-Orozco LE, Saraste A, Kolh P, Rutjes AWS, et al The performance of non-invasive tests to rule-in and rule-out significant coronary artery stenosis in patients with stable angina: A meta-analysis focused on post-test disease probability. Eur Heart J 2018;39(35):3322–30.

Wennberg DE, Kellett MA, Dickens JD, Malenka DJ, Keilson LM, Keller RB. The association between local diagnostic testing intensity and invasive cardiac procedures. JAMA, J Am Med Assoc 1996;275:1161–4.

Wennberg JE, Cooper MM. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. Chicago, IL; 1996.

Wennberg D, Dickens J Jr, Soule D, Kellett M Jr, Malenka D, Robb J, et al The relationship between the supply of cardiac catheterization laboratories, cardiologists and the use of invasive cardiac procedures in northern New England. J Health Serv Res Policy 1997;2:75–80.

Chen J, Fazel R, Ross JS, McNamara RL, Einstein AJ, Al-Mallah M, et al Do imaging studies performed in physician offices increase downstream utilization? An empiric analysis of cardiac stress testing with imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:630–7.

Varga A, Picano E, Cortigiani L, Petix N, Margaria F, Magaia O et al Does stress echocardiography predict the site of future myocardial infarction? A large-scale multicenter study. EPIC (Echo Persantine International Cooperative) and EDIC (Echo Dobutamine International Cooperative) study groups. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:45-51.

Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2004–13.

Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2012;366:54–63.

Mordi IR, Badar AA, Irving RJ, Weir-McCall JR, Houston JG, Lang CC. Efficacy of noninvasive cardiac imaging tests in diagnosis and management of stable coronary artery disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2017;13:427–37.

American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task F, American Society of E, American Heart A, American Society of Nuclear C, Heart Failure Society of A, Heart Rhythm S et al ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 Appropriate Use Criteria for Echocardiography. A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:229-67.

Doherty JU, Kort S, Mehran R, Schoenhagen P, Soman P, Dehmer GJ, et al ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2019 Appropriate Use Criteria for Multimodality Imaging in the Assessment of Cardiac Structure and Function in Nonvalvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:488–516.

Hendel RC, Berman DS, Di Carli MF, Heidenreich PA, Henkin RE, Pellikka PA, et al ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Circulation. 2009;119:e561–87.

Misra T. A Complex Portrait of Rural America. https://www.citylab.com/equity/2016/12/a-complex-portrait-of-rural-america/509828/.

Wickenheiser M. Census: Maine most rural state in 2010 as urban centers grow nationwide. https://bangordailynews.com/2012/03/26/business/census-maine-most-rural-state-in-2010-as-urban-centers-grow-nationwide/.

Annual Report. About Uninsured. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/annual/measure/HealthInsurance/state/ME.

Residence: Rural and Urban. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/healthy-maine/documents/oppforall/b09res.pdf.

Disclosure

Dr. Mylan Cohen serves on the IAC Board of Directors, as the President of the IAC Nuclear/Positron emission tomography Board of Directors, and as a Secretary of the IAC. He has also served as a past president of American Society of Nuclear Cardiology and he is on the editorial board of the Journal of Nuclear Cardiology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This research was funded by the Intersocietal Accreditation Commission (IAC). They also provided data on accreditation sites from the appropriate time period.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The authors of this article have provided a Power Point file, available for download at SpringerLink, which summarizes the contents of the paper and is free for re-use at meetings and presentations. Search for the article DOI on SpringerLink.com.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, J.N., Murray, K.M., Lucas, F.L. et al. Variation in additional testing and patient outcomes after stress echocardiography or myocardial perfusion imaging, according to accreditation status of testing site. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 28, 2952–2961 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-020-02230-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12350-020-02230-0