Abstract

Serous cystic neoplasm (SCN) is a potentially malignant and invasive disease. However, there are no established guidelines regarding the surgical management of SCN. Here, we report a case of SCN with jejunal invasion that ultimately required a distal pancreatectomy with partial resection of the jejunum. The patient was a 65-year-old female who was referred to our department after a diagnosis of SCN in the pancreatic tail. CT and MRI showed a 75-mm multifocal cystic mass with calcifications; the splenic vein and left adrenal vein were entrapped within the tumor. Furthermore, the tumor was in contact with the beginning of the jejunum. Finally, she underwent a posterior radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy with a partial wedge-shaped resection of the jejunum. Histological findings indicated serous cystadenoma. In addition, the tumor cells were found to have infiltrated the jejunal muscularis propria in some areas, suggesting that the tumor had malignant potential. Currently, 14 months have passed since surgery and there is no evidence of metastasis or recurrence. Surveillance and the decision to perform surgical resection should be made based on tumor size and growth rate to avoid malignant transformation as well as to provide SCN patients with organ-sparing, less invasive surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Serous cystic neoplasm (SCN) accounts for 1–2% of all pancreatic tumors and is one of the most frequently encountered cystic tumors in a real clinical setting [1]. Though it is a slow-growing benign lesion [2, 3], it has the potential of transforming into a malignant mass [4, 5]. Nonetheless, the malignancy of SCN accounts for < 1% of all SCN [6,7,8,9,10]. Thus, SCN should be followed up with the possibility of surgical resection in mind. However, there are no established guidelines regarding the surgical management of this potentially malignant disease.

In real-world clinical practice, surgical resection may be indicated in cases that are difficult to distinguish from malignant tumors, that are symptomatic, or have a tendency to grow [11, 12]. Furthermore, unlike other benign pancreatic tumors, SCN can become invasive to surrounding tissues [13, 14]. This unique unfavorable characteristic further complicates the surveillance of SCN. Here, we report a case of SCN with the jejunal invasion that ultimately required a distal pancreatectomy with a partial resection of the jejunum. We also retrospectively evaluated the optimal timing of the surgery in this case and explored what tips might lead to generalization of surgical management for SCN.

Case report

The patient was a 65-year-old female who was referred to our department after a diagnosis of SCN in the pancreatic tail. She had no relevant family history of pancreatic disease. She had undergone an appendectomy after suffering from appendicitis, an oophorectomy for ovarian cysts, a total hysterectomy due to endometriosis, a cholecystectomy related to cholelithiasis, and a pituitary cyst. In November 2016, she received a computed tomography (CT) scan as part of an examination for suspected primary aldosteronism. The CT revealed an unanticipated 35-mm cystic mass with calcification in the pancreatic tail. She was referred to another department at our institution and she underwent endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) (Fig. 1), after which she was diagnosed with pancreatic SCN. Subsequently, she had regular follow-up CT scans in that department. Due to the fact that the tumor size was gradually increasing, she was referred to our department in February 2021.

Endoscopic ultrasonography. a, b EUS revealed a 23 × 23 mm low-isoechoic mass, with clusters of microcysts, in the pancreatic body. The area around the mass was circumscribed and hypoechoic, and the mass had a clear border with its surroundings. c The interior of the mass was rich in blood flow with small cysts

At the time of the initial consultation with our department, there was no chief complaint. The abdomen was flat and soft, and no mass was palpable. Blood tests were within normal limits, including tumor markers, serum carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19-9), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). CT showed a 75-mm multifocal cystic mass with calcifications in the pancreatic tail. It also showed that the splenic vein and left adrenal vein were entrapped within the tumor. Furthermore, the tumor was in contact with the left renal artery and the beginning of the jejunum. There were no findings suggestive of lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis (Fig. 2). Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also confirmed this multifocal cystic mass in the pancreatic tail. The mass extended into the left perirenal region and was found to be in contact with the left renal vein (Fig. 3). Positron emission tomography CT (PET–CT) showed an accumulation of standardized uptake value (SUV) max 4.0 at the lesion site. There were no findings suggestive of lymph node metastasis or distant metastasis (Fig. 4). Tumor biopsy using EUS was not performed. Based on the above aggressive findings, we could not deny the malignant potential and arranged to perform a distal pancreatectomy with splenectomy.

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography image at the time of the initial consultation with our department. a (coronal veiw) The splenic vein was entrapped within the tumor (arrowhead). b (coronal veiw) Contact with left renal vein (arrowhead). c (coronal veiw) The left adrenal vein was entrapped within the tumor (arrowhead). d (sagittal veiw) Contact with the beginning of the jejunum (arrowhead). Compared to the non-invasive area, the honeycomb structure of the invasive area was indistinct (circle)

Magnetic resonance imaging. a T2-weighted image showed a 40-mm multifocal cystic mass, suspected to be a microcystic type SCN. (January 2017) b T2-weighted image showed a 69-mm multifocal cystic mass (yellow arrow). The border between the tumor and the left kidney was clear (yellow arrowhead). (November 2020)

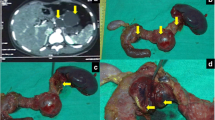

As for the surgical findings, an 80-mm multifocal cystic mass was found in the pancreatic tail. There were no swelling lymph nodes, peritoneal nodules, or liver tumors, suggestive of metastasis. The tumor surface was relatively smooth, and the cysts contained serous fluid. The tumor was close to the left renal artery and vein, but these vessels could be preserved. In contrast, the splenic and left adrenal veins had been invaded by the tumor, requiring a posterior radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy. The tumor was also suspected to be invading the jejunum near the Treitz ligament, requiring a partial wedge-shaped resection of the jejunum. The operation time was 295 min, and the blood loss was 295 g. There were no severe postoperative complications exceeding Grade 2 of the Clavien–Dindo classification, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 11. Since then, she has been followed up without postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Currently, 14 months have passed after surgery, and there is no evidence of metastasis or recurrence.

As for the histological findings, the tumor was located in the tail of the pancreas and measured 62 × 40 mm. It was a serous tumor covered with a fibrous capsule composed of small cysts. Histological findings showed small and large cystic lesions, and the cyst walls were lined with one layer of tumor cells with clear to granular pink cytoplasms. In the cytoplasms of the tumor cells, glycogen was found to be positive for PAS staining and negative for d-PAS staining, and the cytoplasms were positive for α-inhibin. Since there was no evidence of distant metastasis on clinical examination, we diagnosed it as serous cystadenoma, in accordance with the 2010 WHO definition [9]. Although a large portion of the tumor was confined to the pancreatic parenchyma, tumor cells were found to have infiltrated the jejunal muscularis propria in some areas, suggesting that the tumor had malignant potential (Fig. 5).

Pathology specimen. a Gross cross section of the pancreatic body. The neoplasm is well-demarcated, composed of small cysts accompanied by a white fibrotic scar toward the center of the tumor. Gross findings did not reveal any invasion into the jejunum, but histology showed invasion of tumor cells into the jejunal muscularis propria (arrowhead). b The tumor is polycystic, and the cysts contain proteinaceous fluid (scale bar 500 μm). c Cuboidal tumor cells line the lumen of the cyst, and some show low papillary growths (scale bar 100 μm). PAS staining (d) and d-PAS staining (e) highlight the abundant glycogen (scale bar 100 μm). f The cytoplasm was positive for α-inhibin (scale bar 100 μm). g Tumor cells directly infiltrate into the jejunal muscularis propria (arrowhead) (scale bar 200 μm). h Immunostaining (desmin) stains the jejunal muscularis propria and confirms tumor cell infiltration in the jejunal wall (arrow) (scale bar 200 μm). i Tumor cells have clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm and form cysts. There is no histologic difference between the primary and the invasive lesion. (scale bar 100 μm)

Discussion

Pancreatic SCNs have extremely low malignancy potential. Thus, usually, they can be controlled through periodic surveillance, which means they do not commonly mandate surgical resection unless they exhibit aggressiveness or unspecific characteristics that hinder accurate diagnosis [15, 16]. According to a nationwide survey in Japan, surgical resection should be considered (1) when differentiation from other neoplasms such as IPMN, MCN, endocrine tumor, and pancreatic cancer is difficult; (2) when the patient has symptoms or mass effects in the main pancreatic duct; and (3) when the tumor size is large or increasing [11]. In our case, differentiation from other neoplasms with malignant potential was not difficult. In addition, our case had no symptoms or mass effects on the main pancreatic duct. The indication of surgical resection was determined by size-related issues.

Regarding the indication of surgical resection during SCN surveillance, there are some reports discussing size-related issues based on several aspects. In a review of 24 cases of serous cystic carcinoma of the pancreas by Watanabe et al., the average maximum tumor diameter was 7.7 cm, which is larger than the average for all SCN [11]. These results suggested that a larger tumor diameter is linked with a higher possibility of malignancy. In short, we need to recognize the association between tumor size and malignant transformation. Next, there are reports on the relationship between tumor size and symptoms. It has been noted that tumor diameters greater than 4 cm are more likely to affect the main pancreatic duct. Some authors reported that surgery is indicated for tumors 4 cm in diameter or larger because symptomatic cases are more frequent [17]. Too much emphasis may have been placed on post-diagnostic surveillance, mass size, and extraneous symptoms with this case, which may have led to insufficient attention to the unique extrapancreatic invasion of this benign tumor. Surgery was performed before malignancy could develop; however, that meant subjecting the patient to a more invasive procedure than anticipated.

Regarding the relationship between tumor size and extrapancreatic invasion, the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions have prepared a thought-provoking report [18]. In an analysis of 257 pathologically confirmed SCN patients who underwent surgical resection, thirteen tumors (5.1%) (mean size 10.5 cm) showed extrapancreatic invasion. Multivariate analysis showed that tumor diameter and location of the tumor in the pancreatic head were independently associated with extrapancreatic invasion.

Additionally, the relationship between tumor size and the annual tumor growth rate should be considered in the management of patients with SCN. Tseng et al. reported that the median growth rate in patients with pancreatic serous cystadenoma was 0.60 cm/year. Most notably, for tumors < 4 cm at presentation, the rate was 0.12 cm/year, whereas for tumors ≥ 4 cm, the rate was 1.98 cm/year (p = 0.0002) [19]. Similar to that report, our case demonstrated an increasing tumor growth rate in proportion to the tumor size. Specifically, the rate was 4 mm/year at 4 cm or less, 6 mm/year at 4–5 cm, and 20 mm/year at 5 cm or more (Fig. 6). Imaging findings at 4 cm showed no obvious invasion into other organs. This retrospective evaluation of our present case suggested that extrapancreatic invasion was established during the rapid enlargement period. These findings suggest to us that the tumor growing to the size of 4 cm might have signaled the optimal timing for surgical intervention in this case.

Tumor growth rate in this case. (coronal veiw) a (33 mm), b (35 mm), c (37 mm): 4 cm or less: 4 mm/year. d (40 mm), e (43 mm), f (46 mm): 4–5 cm: 6 mm/year. g (54 mm), h (84 mm): 5 cm or more: 20 > mm/year. Yellow arrowhead indicates the tumor. The contrast effect at the border with the small intestine (yellow arrow) becomes indistinct around figure e, which is over 4 cm, suspicious for jejunal invasion

Furthermore, we retrospectively evaluated the relationship between tumor growth rate and tumor size of all surgically resected SCN cases in our department. The scatter plot was generated using Microsoft Excel based on 31 CT examinations of 11 cases (Fig. 7). Figure 7 shows that the tumor growth rate positively varied depending on the tumor size. Notably, we found an exponential increase in tumor growth rate after the tumor diameter exceeded 4 cm. The data suggest that it would be appropriate to perform an imaging examination once a year when the tumor is less than 4 cm in diameter. For SCN cases larger than 4 cm, surgical intervention or semiannual imaging studies are considered appropriate. Although further data accumulation is needed to set a definitive cutoff diameter, we should recognize that larger tumors appear to have a faster growth rate than smaller tumors. Our cases also suggest the need for varying surveillance intervals according to tumor size, regardless of symptoms.

Annual tumor growth rate of surgically resected SCNs in our institution. Quadratic curve plotting the annual tumor growth rate based on tumor diameter for SCN surgery cases in our department. The scatter plot was generated using Microsoft Excel based on 31 CT examinations of 11 cases. The vertical axis is the annual tumor growth rate (mm/year) and the horizontal axis is the tumor diameter (mm). The growth rate is approximately 5 mm/year up to a tumor diameter of 40 mm, after which the growth rate increases exponentially. The difference in slope of the curve was about twofold as y’ = 0.33 at x = 45 mm and y’ = 0.17 at x = 35 mm

CT scan is a common modality for SCN surveillance. CT is useful to search for distant metastases and lymph node metastases while maintaining high reproducibility and objectivity. However, for situations resembling the present case, CT follow-up is potentially insufficient for evaluation of local invasion. It is possible that local invasion into the jejunum and large vessels could have been spotted earlier if surveillance had been performed by EUS. Even though EUS is not a common modality for SCN surveillance at present, in combination with CT, EUS could achieve a stricter level of surveillance, at least in patients with SCN over 4 cm in size.

Microcystic type SCN is generally characterized by a honeycomb appearance on CT or MRI. The SCN in this case was diagnosed as a microcystic type SCN based on imaging findings of clusters of microcysts. However, notably, it was relatively rich in parenchyma cells in the invasive area based on the initial examination on CT and MRI, and the honeycomb appearance seemed to disappear as time passed. In contrast, no trend of disappearance of the honeycomb structure was evident in the non-invasion areas. Although we cannot draw conclusions based solely on the experience of this case, the trend toward loss of honeycomb structure may reflect invasiveness. Due to the relatively rare nature of the disease, it is not easy to establish an evidence-based strategy for SCN. Thus, to provide better surveillance and treatment strategy, it is important to accumulate valuable findings such as what has been uncovered in the present case.

Conclusion

We herein report a case of SCN with jejunal invasion that ultimately required a distal pancreatectomy with partial resection of the jejunum. Surveillance and the decision to perform surgical resection should be made based on tumor size and growth rate to avoid malignant transformation as well as to provide organ-sparing, less invasive surgery for SCN patients.

Data availability

Data will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SCN:

-

Serous cystic neoplasm

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography

- PAS:

-

Periodic acid Schiff

- d-PAS:

-

Diastase-periodic acid Schiff

- IPMN:

-

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm

- MCN:

-

Mucinous cystic neoplasm

References

Horvath KD, Chabot JA. An aggressive resectional approach to cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Am J Surg. 1999;178:269–74.

Wang GX, Wang ZP, Chen HL, et al. Discrimination of serous cystadenoma from mucinous cystic neoplasm and branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm in the pancreas with CT. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45:2772–8.

Dababneh Y, Mousa OY. Pancreatic serous cystadenoma. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2022, StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2022.

George DH, Murphy F, Michalski R, et al. Serous cystadenocarcinoma of the pancreas: a new entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 1989;13:61–6.

Lee SD, Han SS, Hong EK. Solid serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas with invasive growth. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:454–6.

Galanis C, Zamani A, Cameron JL, et al. Resected serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a review of 158 patients with recommendations for treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:820–6.

Chandwani R, Allen PJ. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Annu Rev Med. 2016;67:45–57.

Slobodkin I, Luu AM, Höhn P, et al. Is surgery for serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas still indicated? Sixteen years of experience at a high-volume center. Pancreatology. 2021;21:983–9.

Reid MD, Choi HJ, Memis B, et al. Serous neoplasms of the pancreas: a clinicopathologic analysis of 193 cases and literature review with new insights on macrocystic and solid variants and critical reappraisal of so-called “serous cystadenocarcinoma.” Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1597–610.

Wu W, Li J, Pu N, et al. Surveillance and management for serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas based on total hazards-a multi-center retrospective study from China. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:807.

Kimura W, Moriya T, Hirai I, et al. Multicenter study of serous cystic neoplasm of the Japan pancreas society. Pancreas. 2012;41:380–7.

Wataru KIMURATW. Diagnosis and treatment of serous cystic neoplasm. Suizo. 2018;33:131–9.

Kimura W, Makuuchi M. Operative indications for cystic lesions of the pancreas with malignant potential–our experience. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:483–91.

Jais B, Rebours V, Malleo G, et al. Serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas: a multinational study of 2622 patients under the auspices of the international association of pancreatology and European pancreatic club (European study group on cystic tumors of the pancreas). Gut. 2016;65:305–12.

Hu F, Hu Y, Wang D, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: differential diagnosis and radiology correlation. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 860740.

Huh J, Byun JH, Hong SM, et al. Malignant pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms: systematic review with a new case. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:97.

Sasaki YMH, Uemura K, Hashimoto Y, et al. (2015) Operative indication for serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas—the evaluation of our 12 resected patients. Suizo. 2015;30:585–91.

Khashab MA, Shin EJ, Amateau S, et al. Tumor size and location correlate with behavior of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1521–6.

Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, et al. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg. 2005;242:413–9 (discussion 9-21).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Shari Joy Berman for professionally editing the English draft of this manuscript.

Funding

Institutional sources only.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KY and TW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KI and KH contributed to the review, and/or critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have approved the final article. TW, KI, NK, DI, and YT performed the surgical resection and collected the clinical data. TY and HK contributed to the pathological assessment.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest with regard to the work in the case report.

Informed consent

With regard to this manuscript, consent to publish was obtained from the patient.

Human rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The approval for publication of this case study was waived by our IRB.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamazaki, K., Wakiya, T., Ishido, K. et al. A case of serous cystic neoplasm with tumor growth acceleration leading to extrapancreatic invasion. Clin J Gastroenterol 16, 289–296 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-022-01746-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-022-01746-x