Abstract

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a benign tumor mass composed of chronic infiltration of inflammatory cells and fibrous tissue. IgG4-RD (related disease) in the hepatobiliary system has been widely recognized and includes IgG4-related hepatic IPT. This report describes a patient with IgG4-related hepatic IPT with sclerosing cholangitis. A 75-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for the treatment of rectal cancer. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a low-density mass, 2.5 cm in diameter, in the left lateral lobe. Magnetic resonance imaging showed that the mass was slightly hypointense on T1-weighted images and slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Based on these results, we made a diagnosis of cholangiolocellular carcinoma, and we performed a left hepatectomy. Histopathological examination showed that the mass was composed of fibrous stroma with dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. Immunohistochemically, IgG4-positive plasma cells were observed. The final diagnosis was IgG4-related hepatic IPT with sclerosing cholangitis. IgG4-related IPT is a relatively rare disease that can occur in any organ of the body. Although the accurate diagnosis of IgG4-related hepatic IPT remains difficult, IgG4-RD should be included in the differential diagnosis of liver tumors and histological analysis performed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inflammatory pseudotumor (IPT) is a benign tumor mass composed of chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate and fibrous tissue. IPT develops most frequently in the lung and hepatic IPTs account for only 8% of all extrapulmonary IPTs [1]. Hepatic IPT presents as parenchymal involvement in the liver and may be clinically misdiagnosed as a malignant tumor. Several cases of hepatic IPT associated with immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)-related immune reactions were recently reported. Some cases of hepatic IPT showed IgG4-positive plasma cell-rich infiltration and obliterative phlebitis, which are the pathologic features of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) [2, 3]. AIP is the most common presentation of IgG4-related disease (IgG4-RD) and is often accompanied by sclerosing cholangitis (SC) [4]. We report a case of IgG4-related hepatic IPT with SC in a patient who underwent left hepatectomy with a preoperative diagnosis of malignant tumor.

Case report

A 75-year-old woman was referred to our hospital for the treatment of rectal cancer. At the time of referral, she had no symptoms, such as fever, weight loss, or gastrointestinal symptoms. Chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT) were performed, and the results showed no pulmonary metastasis, but a mass in the lateral segment of the liver. Because the imaging findings of the tumor were not typical, the liver tumor was not suspected to be metastasis of the rectal cancer. The patient first underwent resection of the rectal cancer; the pathological stage was Stage IIa (Japanese Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and Anal Carcinoma-Third English Edition). After 2 months, the patient was readmitted for treatment of the liver tumor.

Preoperative measurements of blood examination revealed serum amylase level of 98 IU/L (normal range 29–132 IU/L) and glucose tolerance was within normal limits. Tumor markers including carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, α-fetoprotein, and des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin were within normal limits, and the tests of hepatitis B surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C virus antibody had negative results. Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT revealed a low-density mass in the left lateral lobe in the noncontrast-enhanced phase (Fig. 1a). The mass showed faint peripheral enhancement and an artery penetrating through the tumor in the arterial phase (Fig. 1b) and delayed enhancement in the central area in the equilibrium phase (Fig. 1c).

Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography. a The tumor was a hypointense mass in the lateral lobe in the non-contrast-enhanced phase, b showed poorly defined peripheral enhancement and an artery penetrating thorough the tumor in the arterial phase, and c showed delayed enhancement in the central area in the equilibrium phase

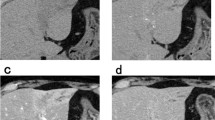

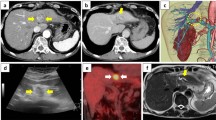

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that the mass was slightly hypointense on T1-weighted images and slightly hyperintense on T2-weighted images (Fig. 2a, b). Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylene-triamine pentaacetic-acid enhanced MRI revealed the tumor had poorly defined peripheral rim-like enhancement in the arterial phase, persistent enhancement in the equilibrium phase, and was entirely hypointense in the hepatobiliary phase (Fig. 2c–e). Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/CT revealed the accumulation of FDG in the tumor was slightly higher than the surrounding liver parenchyma and the standardized uptake value maximum (SUV max) was 2.5. Except for the accumulation in the right pulmonary hilum, no abnormal accumulations were observed in other organs. The accumulation in the right hilum was not considered a significant finding because the nodule had been noted on a previous CT scan and did not show a trend of increase over time (Fig. 3a–c). Although these imaging findings were not typical for either liver metastasis or hepatocellular carcinoma, the enhancement patterns of the CT and MRI images and the signs of penetration of intrahepatic vessels through the tumor were typical of cholangiolocellular carcinoma. Therefore, we diagnosed the tumor as a cholangiolocellular carcinoma, and a possible differential diagnosis was scirrhous-type hepatocellular carcinoma and mixed hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma. The possibility that the mass was malignant could not be ruled out, and the patient herself requested surgical removal of the mass. For these reasons, laparotomy was performed. Intraoperative contrast-enhanced ultrasonography showed the tumor as a hypo-enhancement, and the artery was seen penetrating the tumor in the early to late vascular phase (within 1 min after intravenous injection of perflubutane [Sonazoid®, Daiichi-Sankyo, Co., Ltd., Tokyo]) (Fig. 4a). The tumor showed a contrast defect and was well-demarcated in the Kupffer phase (more than 10 min after injection) (Fig. 4b). Because the tumor was close to the umbilical portion, a left hepatectomy was performed to secure the resection margin. Macroscopically, a cross-section of the resected specimen revealed a white-colored, well-circumscribed, solid tumor located near the bile ducts (Fig. 5). The tumor size was 2.3 cm. Histopathological examination of the tumor showed fibrosis accompanied by lymphoplasmacytic infiltration (Fig. 6a) and obliterative phlebitis. The bile duct in the vicinity of the tumor exhibited fibroinflammatory thickening with prominent lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and lymphoid follicles. Immunohistochemically, abundant plasma cells were positively stained by anti-IgG4 antibody (Fig. 6b) at a density of > 100 IgG4-positive plasma cells per high-powered fields, and the IgG4/IgG ratio was > 40%. The final diagnosis was IgG4-related hepatic IPT with SC. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course, and the postoperative IgG4 serum level was 52.4 mg/dl (normal value < 134 mg/dl).

Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine-enhanced MRI. a The tumor was entirely hypointense on the unenhanced T1-weighted image and b partially hyperintense on the unenhanced T2-weighted image. c Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine-enhanced imaging showed the tumor had poorly defined peripheral enhancement in the arterial phase, d poorly defined prolonged mild enhancement in the equilibrium phase, and e was entirely hypointense in the hepatobiliary phase

Intraoperative Sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography. a The tumor was hypovascular, and the artery was seen penetrating the tumor in the early vascular phase (within 1 min after intravenous injection of Sonazoid). b The tumor showed a contrast defect and was well-demarcated in the Kupffer phase (more than 10 min after injection)

Histopathological examination of the liver tumor. a Histology revealed lymphoplasmacytic infiltration within dense fibrotic nodule. No cancer cells were observed. (Hematoxylin–eosin, × 400). b Most of the infiltrating plasma cells immunoreacted to anti-immunoglobulin G4 antibody (diaminobenzidine, × 400)

Discussion

This report described a patient with asymptomatic hepatic IPT as a manifestation of IgG4-RD. In general, hepatic IPTs are difficult to differentiate from malignant tumors, as their incidence is rare and imaging findings are varied. Recently, hepatic IPT with SC was reported in the spectrum of IgG4-RD [3].

IgG4-RD is a systemic disease that can involve various organs, including the pancreas, hepatobiliary system, salivary gland, kidney, and perivascular area. Histologically, it presents as marked infiltration of lymphocytes and IgG4-positive plasma cells as well as fibrosis of unknown etiology [5].

IgG4-SC associated with AIP is the most common manifestation, whereas isolated IgG4-SC without AIP is uncommon [6]. In the consensus guidelines, serum IgG4 (> 135 mg/dL) was included as part of the diagnostic criteria for IgG4-RD [7]. IgG4-related IPT with SC had an inconsistent appearance in radiologic studies, and no specific image findings have been reported yet [8]. The imaging characteristic of IPT varies because it depends on the proportion of inflammatory cells and fibrosis within the lesion as well as the pathological changes in the course of disease progression. The FDG uptake of IPT is also vary according to the inflammatory stage, and the SUV max depends on its tumor volume, size, degree of inflammation. Therefore, radiologic differentiation of IPT from malignancies is difficult. Histologically, the three major features for the diagnosis of IgG4-RD are dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, storiform fibrosis, and obliterative phlebitis. An IgG4-positive/IgG-positive plasma cell ratio > 40% is also necessary for the diagnosis [3]. Steroid treatment and observation of the response to the therapy has been recommended; however, patients with diabetes and immunocompromised condition are at an increased risk of developing a hepatic abscess or acute cholangitis with steroid treatment [9].

We performed surgical liver resection, as the patient had a history of rectal cancer and cholangiolocellular carcinoma was suspected according to the enhancement patterns, the signs of portal vessel penetration into the tumor and the accumulation of FDG was slightly higher than the surrounding liver parenchyma in imaging findings.

We found 19 cases in the literature that seemed to be IgG4-related hepatic IPT with SC, which presented as a mass-forming tumor in the liver parenchyma [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Table 1 summarizes the clinical features of these cases and our report. The male/female ratio was 16:4, and the median age of the patients was 60 years (range 48–79 years). The median IgG4 serum level was 222 mg/dl (range 32.3–6280 mg/dL). The tumor location did not show any significant trend. The most frequent initial clinical diagnosis based on the laboratory data and images was IgG4-related hepatic IPT (n = 11, 55%) followed by intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (n = 4, 20%), metastatic tumor (n = 3, 15%), and liver abscess (n = 2, 10%). A percutaneous needle biopsy was performed in 15 patients (75%), resulting in a precise diagnosis of IgG4-related hepatic IPT in 14 patients (70%). Five patients (25%) were treated by surgical resection without percutaneous needle biopsy. An accompanying IgG4-RD in other organs was seen in eleven patients (55%); however, AIP coexisted only in four patients (20%). Two patients (10%) had concomitant malignant disease.

The etiology of IgG4-RD is unknown. It is hypothesized that cancer may represent a trigger for IgG4-RD in certain patients, because a history of malignancy is 3.5-times higher in patients with IgG4-RD than in the general population [27]. As IgG4-RD sometimes coexists with malignant disease in other organs, considerable care must be taken when performing systemic examination for metastatic tumor. In our case, liver tumor was found at the time of diagnosis of colorectal cancer, and liver metastasis or primary liver tumor should be considered as a differential. IgG4-related hepatic IPT, a benign disease, was not included in the differential because of the lack of lesions in other organs. In addition, since no biopsy was performed, no pathological information was available and malignant disease could not be ruled out, a policy of resection was decided. IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumor should be included in the differentiation of liver tumors with atypical imaging findings. It is also important to make a histologic diagnosis, such as biopsy.

Despite aggressive preoperative evaluation, it is difficult to differentiate IgG4-SC without AIP from malignancy as shown in our case. Histopathological diagnosis is essential, and percutaneous needle biopsy remains the cornerstone for the definite diagnosis of IgG4-related IPT.

Conclusion

We encountered a case of IgG4-related hepatic IPT without AIP that was concomitant with rectal cancer. As it is difficult to distinguish hepatic IPT from malignancy by clinical presentation or imaging studies, a needle biopsy of the tumor would be a feasible strategy. The possibility of a pseudotumor should be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of masses in the liver in order to avoid major surgical resection.

Abbreviations

- AIP:

-

Autoimmune pancreatitis

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

- IgG4:

-

Immunoglobulin G4

- IgG4-RD:

-

IgG4-related disease

- IPT:

-

Inflammatory pseudotumor

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- SC:

-

Sclerosing cholangitis

References

Park JY, Choi MS, Lim YS, et al. Clinical features, image findings, and prognosis of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver: a multicenter experience of 45 cases. Gut Liver. 2014;8:58–63.

Zen Y, Fujii T, Sato Y, et al. Pathological classification of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with respect to IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:884–94.

Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1181–92.

Zen Y, Harada K, Sasaki M, et al. IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis with and without hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor, and sclerosing pancreatitis-associated sclerosing cholangitis: do they belong to a spectrum of sclerosing pancreatitis? Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1193–203.

Stone JH, Zen Y, Deshpande V. IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:539–51.

Ghazale A, Chari ST, Zhang L, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-associated cholangitis: clinical profile and response to therapy. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:706–15.

Shimosegawa T, Chari ST, Frulloni L, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: guidelines of the International Association of Pancreatology. Pancreas. 2011;40:352–8.

Murakami T, Tsurusaki M. Hypervascular benign and malignant liver tumors that require differentiation from hepatocellular carcinoma: key points of imaging diagnosis. Liver Cancer. 2014;3:85–96.

Shibata M, Matsubayashi H, Aramaki T, et al. A case of IgG4-related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor replaced by an abscess after steroid treatment. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;2(16):89.

Uchida K, Satoi S, Miyoshi H, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumors of the pancreas and liver with infiltration of IgG4-positive plasma cells. Intern Med. 2007;46:1409–12.

Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Ohara H, et al. IgG4-related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor with sclerosing cholangitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2009;2:7029.

Kim F, Yamada K, Inoue D, et al. IgG4-related tubulointerstitial nephritis and hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor without hypocomplementemia. Intern Med. 2011;50:1239–44.

Horiguchi S, Ikeda F, Shiraha H, et al. Diagnostic usefulness of precise examinations with intraductal ultrasonography, peroral cholangioscopy and laparoscopy of immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:370–3.

Ahn KS, Kang KJ, Kim YH, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumors mimicking intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma of the liver; IgG4-positivity and its clinical significance. J Hepatobil Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:405–12.

Iizuka T, Shibusawa N, Yoshida S, et al. Case report: a case of Igg4-associated autoimmune pancreatitis accompanying liver inflammatory pseudotumor. Nippon Naika Gakkai Zasshi. 2012;101:468–71.

Lee YS, Lee SH, Lee MG, et al. Immunoglobulin G4-related disease mimicking unresectable gallbladder cancer. Gut Liver. 2013;7:616–20.

Yang L, Jin P, Sheng JQ. Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-Rd) affecting the esophagus, stomach, and liver. Endoscopy. 2015;47(S 01):E96–7.

Mulki R, Garg S, Manatsathit W, et al. IgG4-related inflammatory pseudotumour mimicking a hepatic abscess impending rupture. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015211893.

Malik SM, Raina A, Hartman DJ. Immunoglobulin G4-related pseudotumor presenting as metastatic colon cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:e1-2.

Matsushima H, Kaibori M, Ishizaki M, et al. Two cases of IgG4-related disease mimicking hepatic cancer. Nihon Rinsho Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2016;77:2127–32.

Fujisaki H, Ito N, Takahashi E, et al. A case of inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver with tumor enlargement. Nihon Gekakei Rengo Gakkaishi. 2016;41:105–9.

Kataoka K, Achiwa K. Autoimmune pancreatitis and Igg4-related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor complicated by an impacted pancreatic stone at the major papilla during steroid treatment. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2017;114:2158–66.

Miyajima S, Okano A, Ohana M. Immunoglobulin G4-related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor invading the abdominal wall. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;10:57–62.

Adachi K, Hashimoto K, Nonaka R, et al. A case of an Igg4-related inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver showing enlargement that was difficult to differentiate from hepatic cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2017;44:1922–4.

Kim YR, Lee YH, Choi KH, et al. Imaging findings of IgG4-related hepatopathy: a rare case presenting as a hepatic mass. Clin Imaging. 2018;51:248–51.

Patel H, Nanavati S, Ha J, et al. Spontaneous resolution of IgG4-related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor mimicking malignancy. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2018;12:311–6.

Yamamoto M, Takahashi H, Tabeya T, et al. Risk of malignancies in IgG4-related disease. Modern Rheumatology. 2012;22:414–8

Acknowledgements

I offer my sincere appreciation for the learning opportunities provided by my department and cannot express enough thanks to all members in our hospital for their support and encouragement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and no financial arrangement with any company.

Ethical approval

All procedures followed have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Informed consent

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Itazaki, Y., Einama, T., Konno, F. et al. IgG4-related hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor mimicking cholangiolocellular carcinoma. Clin J Gastroenterol 14, 1733–1739 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-021-01526-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-021-01526-z