Abstract

We experienced a rare case of acute pancreatitis caused by Candida infection. A 52-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a chief complaint of abdominal pain. Blood tests revealed high amylase and hepatobiliary enzyme abnormalities, and the patient was hospitalized for acute pancreatitis. Abdominal computed tomography showed a 15-mm space-occupying lesion at the parenchyma of the pancreatic head. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was performed after conservative treatment, which revealed a cystic lesion with a suspected solid component inside involving both lower bile duct and pancreatic duct. Cytology of collected bile and pancreatic juice revealed innumerous hyphae and spores morphologically consistent with Candida spp., as did endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of the tumor site. Empiric therapy with oral fluconazole resulted in reduction of the space-occupying lesion 3 months after discharge. However, acute pancreatitis recurred about 1 year and 6 months after discharge. After conservative treatment was carried out again, the same lesion was fenestrated by endoscopic sphincteroplasty, and its internal solid components were resected using a basket catheter. Pathological analysis confirmed the presence of fungus balls and degenerated substances. Candida Albicans was identified by fungal culture examination. After the excretion of the fungus balls, pancreatitis did not recur thereafter during outpatient follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Generally, the most common causes of acute pancreatitis are excessive alcohol consumption and the presence of gallstones, as well as unknown causes in idiopathic cases [1]. Other various causes include surgery and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), pancreaticobiliary carcinoma, anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary ducts, disease of the duodenal papilla, hyperlipidemia, and drug induced. Pancreatic carcinoma is thought to cause acute pancreatitis in 3% of cases in the US [2]. Other low-frequency causes listed in the 2015 Japanese guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis include genetic predisposition, pregnancy, trauma, hyperparathyroidism, end stage renal failure, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positivity and other viral infections, bacterial infection, and infection with fungal (Aspergillus) parasites [3]. However, there have been only a few reports of pancreatitis caused by Candida species. Since a treatment strategy depends on an etiology, it is important to identify the accurate cause of acute pancreatitis, for recurrent patients.

Here, we report a case of acute pancreatitis due to Candida infection that was distinguished from acute pancreatitis caused by pancreatic carcinoma. The patient provided informed consent for the publication of this report.

Case report

A 52-year-old male patient visited an outpatient clinic complaining of intermittent epigastric pain and vomiting for 3 months. He was not on any medications. He denies consuming alcohol on daily basis nor binge drinking. He had a history of surgery for duodenal ulcer perforation 1.5 years prior to this presentation followed by the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. His blood test revealed elevated amylase and hepatobiliary enzymes, white blood cell count and C-reactive protein but serum immunoglobulin G4, lipid markers or tumor markers were within normal limit (Table 1). He was negative for HIV antibody. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) examination at the initial hospital revealed a tumor without enhancement in the parenchyma of the pancreatic head. There was no finding on CT to suggest cholelithiasis and chronic pancreatitis. After a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, he was hospitalized for 3 days and conservative treatment relieved his symptoms and improved blood test results. Then he was transferred to our hospital for further investigation.

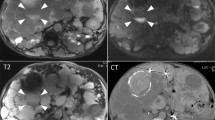

On admission at our hospital, his body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure were 36.4 °C, 87 beats/min, and 104/61 mmHg, respectively. Physical examination of the patient revealed that he was alert and was experiencing tenderness in his upper abdomen. Abdominal CT revealed a low-density area 15 mm in diameter at the head of the pancreas without fluid collection around the pancreas or pancreatic necrosis (Fig. 1a). T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a similar low-signal node between the pancreatic and bile ducts (Fig. 1b). Endoscopic color Doppler ultrasound examination mainly demonstrated an iso-echoic lesion without marked vascularity. On the 7th day, ERCP was performed to identify the cause of acute pancreatitis. Although the duodenal papilla was normal, a cystic lesion with connections between the main pancreatic duct and common bile duct was found (Fig. 1c, d). A solid component suspicious of a tumor existed inside the cystic lesion. Then intraductal ultrasound (IDUS) was performed via the pancreatic duct, which revealed a similar circular echoic mass located in the parenchyma of the pancreatic head (Fig. 1e, f). Connection between the pancreatic and bile ducts via the tumor was, therefore, suspected (Fig. 1g). Since the mass seemed to be atypical (either a pancreatic or biliary tract tumor), cytological examination was carried out by placing a nasal drainage tube in both the bile and pancreatic ducts. Over 2 days, cytology specimens were extracted six times from each stent. No atypical cells suggesting malignancy were detected, however, collected bile and pancreatic juice showed innumerous hyphae and spores morphologically consistent with Candida spp. (Fig. 2a, b). Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) using a 25-gauge needle (Expect™, Boston Scientific Natick, MA, USA) and a 22-gauge needle (EZ Shot 2™, Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA) at the tumor site was also performed to exclude the possibility of contamination during the cytology procedure. Again, malignancy was denied and histological diagnosis confirmed the collection of yeast-like components that were morphologically consistent with Candida spp. (Fig. 2c–e). We finally diagnosed the lesion as a fungus ball resulted from Candida infection. Therefore, he was given oral fluconazole for 28 days at a dose of 200 mg/day and discharged. MRI examination at 3 months after discharge showed a reduction of the pancreatic head mass.

Abdominal imaging and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) at initial investigation. Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans revealed a low-density area with a diameter of 15 mm at the parenchyma of the pancreatic head (black arrow) (a). Similarly, T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging revealed a low-signal area (black arrow) between the main pancreatic duct (white single arrow) and the common bile duct (white double arrow) (b). The guide-wire inserted from the pancreatic duct (white single arrow) during ERCP strayed into the bile duct (c). Conversely, the guide-wire inserted from the bile duct (white double arrow) strayed into the pancreatic duct (d). IDUS revealed a solid component suspicious of a tumor inside the cystic lesion (arrows) located outside of the pancreatic duct (e, f). The position of the tumor is indicated by the schema (g)

Cytological and histological analysis at initial investigation. Collected bile and pancreatic juice contained many hyphae and spores that appeared to be morphologically consistent with Candida (a, b). Histological analysis of fine needle aspiration specimens revealed many hyphae and spores that appeared to be morphologically consistent with Candida: hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×60 magnification (c), Grocott stain, ×60 magnification (d), and periodic acid-Schiff diastase stain, ×60 magnification (e)

Nevertheless, acute pancreatitis recurred about 1 year and 6 months after discharge. Blood examination revealed increased white blood cell count, CRP and serum amylase. Abdominal CT confirmed the presence of the known low-density area, as well as fluid collection around the pancreas. Parenchyma of the pancreas was relatively enhanced on CT without an area suggesting necrosis. After conservative treatment, we performed endoscopic ultrasonography and ERCP. The cystic change around the tumor was clearer in this examination than in the previous one (Fig. 3a, b). After cystic lesions were fenestrated using endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), the internal solid components were resected with a basket catheter (Fig. 3c, d). With regards to removal of the fungus ball, the guidewire proceeded directly into the cystic lesion thus EST was carried out. The excised component was a yellowish brittle substance and appeared to be different from a neoplastic tissue. Upon pathologic examination, main body of the lesion was found to be composed of degenerated substances, with adhesion of Candida spp. (Fig. 4a, b). Finally, Candida Albicans was detected in a culture test. Following treatment, the patient’s pancreatic enzyme levels promptly returned normal. He was subsequently followed for 1 year after the removal of the fungus ball, with both MRI and CT examinations confirming disappearance of the tumor and no recurrence of pancreatitis.

Endoscopic ultrasound and ERCP at recurrence. Endoscopic color Doppler ultrasound examination demonstrated a mainly iso-echoic lesion (arrow) without marked vascularity at the parenchyma of the pancreatic head (a). ERCP examination revealed a space-occupying lesion at the parenchyma of the pancreatic head (b). After endoscopic sphincteroplasty, the space-occupying lesion was discharged using a basket catheter (c) and a space-occupying lesion disappeared on ERCP (d)

Discussion

Acute pancreatitis has been reported to have a variety of causes. In our case, the patient did not present with any potential causes such as cholelithiasis, chronic pancreatitis, dyslipidemia, or HIV infection, nor did he have any history of drug or excessive alcohol consumption. Therefore, we determined that Candida infection was the cause of his pancreatitis. Although there is a case report on acute pancreatitis caused by Candida infection of intact pancreatic parenchyma [4], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of acute pancreatitis caused by a fungus ball due to Candida infection.

Infections of the pancreaticobiliary system are instead caused by intestinal microbial communities, with Candida infection generally not being reported as problematic. Analysis of 2834 cases of autopsy following candidiasis by Okuhira et al. found only 0.6% and 1.3% of deep-seated candidiasis cases resulted in biliary and pancreatic infection, respectively [5]. Fujikawa et al. also reported that while deep mycosis was observed in 46 (7.3%) of 630 autopsy cases, only three cases involved fungal infections of the pancreas [6]. Thus, Candida infection of the pancreas is considered a rare pathology.

In addition, it is generally thought that acute pancreatitis facilitates the onset of isolated Candida infection, rather than being the direct result of it. There have been reported instances of Candida spp. being detected from cultured specimens after the treatment of pancreatitis using the step-up approach of endoscopic or surgical necrosectomy [7, 8]. More recently, risk factors and outcome of fungal infections in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis and pseudocysts are reported [9]. In our case, however, there was no evidence in the images taken by the patient’s previous doctor of fluid collection around the pancreas, nor of a necrotic lesion.

Several pathological conditions may lead to the development of pancreatitis after Candida infection. We particularly considered three pathological states that can occur before pancreatitis: obstruction of the pancreatic duct by a fungus ball; bile reflux to the pancreatic duct via a fungus ball; and direct stimulation by Candida Albicans. Since there was no evidence of main pancreatic duct dilatation and/or protein plugs [10], we assumed pancreatitis in our case was due to direct stimulation to the pancreatic duct by Candida Albicans. Namely, the Candida infection presumably occurred in the parenchyma of the pancreatic head between bile and pancreatic ducts post-duodenal ulcer perforation. Then repeat inflammation led to the connection between the two ducts. Indeed, there are few reports to suggest intraductal candidiasis causing acute pancreatitis in patients with chronic pancreatitis [11, 12]. This is a very rare case of pancreatitis caused by Candida infection, indeed, being successfully resolved by endoscopic treatment. Furthermore, we assumed the infection of Candida itself was caused by mucosal break down in the duodenum when he had a duodenal ulcer perforation 1.5 year prior to the initial onset of pancreatitis despite not being immune suppressed, suggesting the association between abdominal surgery and Candida infection. Candida spp. has been previously reported to cause an intraperitoneal infection after upper gastrointestinal perforation [13]. Although it is not proven in our case, helicobacter pylori infection or eradication therapy might have increased the risk of Candida infection or proliferation, respectively [14].

In conclusion, we experienced a case of acute pancreatitis caused by Candida infection. It is necessary to raise Candida infection in the differential diagnosis as a potential cause of pancreatitis, particularly in patients who are immune suppressed, susceptible to infection or who have a history of abdominal surgery.

References

Banks PA. Epidemiology, natural history, and predictors of disease outcome in acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:226–30.

Balthazar EJ. Pancreatitis associated with pancreatic carcinoma. Pancreatology. 2005;5:330–44.

Parenti DM, Steinberg W, Kang P, et al. Infectious causes of acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1996;13:356–71.

Hammer MM, Lingxin Z, Stoll JM, et al. Candida albicans pancreatitis in a child with cystic fibrosis post lung transplantation. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46:575–8.

Okudaira M, Kume H, Yamada N, et al. Fungus infections of the hepatobiliary system and the pancreas. Kan-tan-sui. 1985;10:765–70 (in Japanese).

Fujikawa J, Kawaguchi K, Kobashi Y, et al. Candidiasis of the pancreas and biliary tract. Tan-to-sui. 1989;10:1081–8 (in Japanese).

Calandra T, Schneider R, Bille J, et al. Clinical significance of Candida isolated from peritoneum in surgical patients. Lancet. 1989;16:1437–40.

Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Vege SS. Intra-abdominal fungal infections complicating acute pancreatitis: a review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1188–92.

Reuken PA, Albig H, Rödel J, et al. Fungal infections in patients with infected pancreatic necrosis and pseudocysts: risk factors and outcome. Pancreas. 2018;47:92–8.

Tringali A, Lemmers A, Meves V, et al. Intraductal biliopancreatic imaging: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) technology review. Endoscopy. 2015;47:739–53.

Csaba T, Hyon-Seok L, Sebastian H, et al. Rapidly growing mass in the pancreas: intraductal Candida infection in a chronic recurrent pancreatitis. Case Rep Clin Pathol. 2014;1:146–50.

Chung RT, .Schapiro RH, Warshaw AL. Intraluminal pancreatic candidiasis presenting as recurrent pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1532–4.

Sandven P, Qvist H, Skovlund E, et al. Significance of Candida recovered from intraoperative specimens in patients with intra-abdominal perforations. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:541–7.

Khomeriki S. Standard therapeutic regimens in H. pylori infection leads to activation of transitory fungal flora in gastric mucus. Eksp Klin Gastroenterol. 2014;5:16–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Kazuhiro Tange, Tomoyuki, Yokota, Kotaro Sunago, Michiko Aono, Hironori Ochi, Shunji Takechi, Toshie Mashiba, Akira I. Hida, Yumi Ohshiro, Koji Joko, Teru Kumagi, Yoichi Hiasa declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human and/or animal rights

This study does not include any data about human subjects.

Informed consent

This case report does not involve human subjects and does not apply to giving informed consent.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tange, K., Yokota, T., Sunago, K. et al. A rare case of acute pancreatitis caused by Candida Albicans. Clin J Gastroenterol 12, 82–87 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-018-0896-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-018-0896-7