Abstract

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have provided substantial benefit in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with unprecedented results in terms of survival. However, the identification of reliable predictive biomarkers to these agents is lacking and multiple clinicopathological factors have been evaluated. The aim of this study was to analyze the potential role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in patients with pretreated NSCLC receiving nivolumab.

Methods

This was a retrospective multicenter study involving 14 Italian centers, evaluating the role of some laboratory results in patients with NSCLC treated with nivolumab in the second or later lines of therapy for at least four doses and with a disease re-staging.

Results

A total of 187 patients with available pretreatment laboratory results were included. NLR levels below 5 were associated with an improvement in terms of both progression-free survival (PFS) (p = 0.028) and overall survival (OS) (p = 0.001), but not in terms of overall response rate (ORR) or disease control rate (DCR). Moreover, PLR levels below 200 were associated with longer PFS (p = 0.0267) and OS (p = 0.05), as well as higher ORR (p = 0.04) and DCR (p = 0.001). In contrast, LDH levels above the upper normal limit (UNL) were not associated with significant impact on patient outcomes.

Conclusions

Patients with pretreated NSCLC and high pretreatment levels of NLR and PLR may experience inferior outcomes with nivolumab. Therefore, in this subgroup of patients with poor prognosis the use of alternative therapeutic strategies may be a valuable option, especially in programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1)-negative patients and/or in the presence of other additional poor prognostic factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

To identify potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers for nivolumab in unselected patients with pretreated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). |

What was learned from the study? |

This study showed that pretreatment levels of some easy to determine serum biomarkers, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), are associated with outcome in patients with NSCLC treated with nivolumab. |

High NLR levels (≥ 5) at baseline are associated with shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). |

High PLR levels (≥ 200) at baseline are associated with shorter PFS and OS, as well as lower overall response rate and disease control rate. |

Introduction

The therapeutic landscape of advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) has been recently revolutionized with the clinical introduction of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) targeting the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death 1 ligand (PD-L1) axis with unprecedented results in terms of overall survival in different clinical settings [1, 2]. Nivolumab is a therapeutic option in patients with NSCLC progressing after platinum-based chemotherapy in both squamous and non-squamous histology, independently of PD-L1 expression [3, 4]. Immunotherapy has the notorious ability to induce highly durable tumor responses [5] and NSCLC is not an exception, with reported 3-year survival rates of 17% in the two pivotal trials with nivolumab in pretreated NSCLCs [6]. Therefore, the identification of predictive biomarkers is crucial for the optimal selection of patient candidates for second-line therapy. However, there are no currently approved predictive biomarkers for nivolumab in NSCLC and the role of immunohistochemical (IHC) expression of PD-L1, used as selection criteria for pembrolizumab in both first- and second-line therapy [7, 8], is controversial. Hence, there is still a high unmet medical need and novel additional clinical and biomolecular parameters allowing proper patient selection are eagerly awaited.

Inflammation is an established hallmark of cancer and has a central role in tumor promotion and progression [9]. Multiple markers of systemic inflammation have been correlated with poor outcome in multiple solid tumors, including NSCLC, and recently some authors have suggested a possible predictive role of peripheral markers of inflammation in patients with NSCLC treated with nivolumab [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Furthermore, some studies have also reported poorer outcomes in patients with baseline lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels [15], a known poor prognostic marker in solid tumors, with a well-established role in malignant melanoma. However, most of these studies were conducted in small cohorts of patients and/or in single Institutions.

Herein, we analyzed the potential role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and LDH levels in a large, retrospective, multi-institutional study conducted in 14 Italian oncology centers in patients with advanced pretreated NSCLC receiving nivolumab as second or subsequent line of therapy for at least four administrations.

Methods

This was a retrospective multicenter study involving 14 Italian oncology centers, evaluating the role of clinicopathological, laboratory, and radiological characteristics of patients with NSCLC treated with nivolumab in second or later lines of therapy. All patients consented to an institutional review board-approved protocol. The trial protocol was previously approved by the Ethics Committee of the coordinating center (Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome) on 2 March 2018 (approval no. 23/18 OSS ComEt CBM) and all the patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: age over 18 years; cytological and/or pathological confirmed NSCLC; stage IIIB or IV (recurrent or metastatic) according to TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) version VIII; treatment with nivolumab as monotherapy after at least one previous line of therapy for advanced disease; at least four doses of therapy and a disease re-staging. Radiographic assessment was made locally according to the RECIST 1.1 criteria and only patients with measurable disease were included. All patients were treated with nivolumab at the dose of 3 mg/kg i.v. every 2 weeks until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The treatment period under analysis was from April 2015 to May 31, 2018 (data collection closing date).

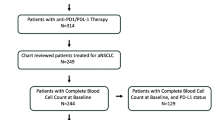

Patients with available baseline laboratory results (absolute neutrophil count, absolute lymphocyte count, platelet count, and LDH) within 30 days before the first course of nivolumab were included in the present analysis (Fig. 1).

NLR was calculated by dividing absolute neutrophil counts by lymphocyte counts, while PLR was calculated by dividing thrombocyte counts by lymphocyte counts. Patients were dichotomized according to pre-specified cutoff values of NLR ≥ 5 vs. NLR < 5 and PLR ≥ 200 vs. < 200, which have been previously validated [10, 12,13,14]. LDH levels over the upper normal limit (UNL) were considered high [15, 16].

Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Overall survival (OS) was defined as time from nivolumab start to death and progression-free survival (PFS) as time from treatment start to progressive disease (PD) or death from any cause. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Survival curves were compared using the log-rank test. To estimate the hazard ratio (HR), Cox regression analysis was used. Overall response rate (ORR) was defined as the sum of partial response (PR) and complete response (CR), while disease control rate (DCR) was calculated as the sum of ORR and stable disease (SD). Multivariate analysis for the most significant variables was performed using the Cox model. Analyses were carried out using R version 3.3.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS software (version 20.00, SPSS, Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was assumed if p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 187 patients with available pretreatment laboratory results were included in the present study. Characteristics of patients can be seen in Table 1.

Median age was 67 years (range 34–83) and there was a higher proportion of male patients (73.3%) and current/former smokers (90.1%). Patients had mostly an ECOG performance status (PS) between 0 and 1, with only a small portion of patients having an ECOG PS 2 (3.7%). PD-L1 status, as determined by IHC, was known in only a small proportion of patients (8%). All patients had received at least one previous treatment line. Nivolumab was used as second-line therapy in 70% of patients. Median number of metastatic sites at baseline was 2, with 41.8% of patients having three or more metastatic sites.

Treatment was discontinued because of adverse events temporarily and permanently in 22 and 14 patients, respectively.

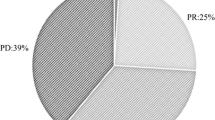

Activity of nivolumab in the study population is listed in Table 2.

Median PFS and OS in the study population were 7.0 months (95% CI 6.0–10.0) (Fig. 2a) and 13.0 months (95% CI 11.0–16.0) (Fig. 2b), respectively.

Low NLR levels (NLR < 5) were associated with a statistically significant improvement in terms of both PFS (7.0 vs. 4.0 months, HR 0.64; p = 0.028) and OS (15.0 vs. 6.0 months, HR 0.48; p = 0.001) (Fig. 3), but not in terms of ORR or DCR (Table 3) compared with high NLR values (NLR ≥ 5).

Moreover, PLR levels below 200 were associated with longer PFS (7.0 vs. 4.0 months, HR 0.67; p = 0.0267) and OS (15.0 vs. 11.0 months, HR 0.66; p = 0.05) (Fig. 4), as well as higher ORR (p = 0.04) and DCR (p = 0.001) (Table 3). The negative impact of high NLR and PLR levels on OS was confirmed in both univariate and multivariate analyses (Table 4).

Finally, we analyzed LDH levels in a proportion of patients with available data (108/187 patients). LDH levels above UNL (upper limit normal) were not associated with significant differences either in PFS (7.0 vs. 8.0 months, HR 0.95; p = 0.84) or in OS (15.0 vs. 14.0 months, HR 0.86; p = 0.582) (Fig. 5). In addition, no differences were observed in ORR and DCR (Table 3) between the two subgroups of patients.

Discussion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have provided substantial benefit in NSCLC with unprecedented results in terms of overall survival in both first- and second-line therapy. However, the identification of reliable predictive biomarkers for these agents is lacking and multiple clinicopathological factors have been evaluated to date [17].

Lymphocytes play a central role in the action of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents and their activation and intratumor invasion are necessary for antitumor immune response reactivation. However, the immune response is the results of multiple interactions between T cells and other regulatory cells, including neutrophils, and they are critical in forming the immune environment. Indeed, neutrophils have recently proved to play pleiotropic actions in cancer–immunity interactions, generating an immunosuppressive environment through the production of chemokines and cytokines that are involved in complex cross talk with other immune cells [13, 16]. Given their peculiar mechanism of action, alterations in the relative proportion of peripheral blood leukocytes may influence the efficacy of ICIs.

Inflammation is an established hallmark of cancer and plays a central role in tumor promotion and progression [9]. Therefore, it is not surprisingly that multiple markers of systemic inflammation have been correlated with poor outcome in multiple solid tumors, including NSCLC.

Neutrophils dominate the immune landscape of NSCLC and, in addition to the well-known role in host defense, have been recently associated with important and significant actions in tumor biology with both anti- (N1 phenotype) and pro-tumor (N2 phenotype) functions, probably in a context-dependent fashion [18,19,20].

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is a marker of chronic inflammation and reflects the alterations in the peripheral blood leukocytes associated with inflammation. This marker has been extensively associated with poor outcomes in NSCLC and other solid tumors in the pre-immunotherapy era and, more recently, it has been associated with poor outcomes in patients with pretreated NSCLC undergoing nivolumab therapy with different cutoff values [10, 13, 14, 21]. Moreover, some studies have reported a potential predictive role for changes of NLR levels during treatment with nivolumab [12, 22, 23], suggesting that treatment with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 agents may be associated with a broad spectrum of changes in the immune microenvironment of the tumor, leading to decrease in the neutrophil count and increase in the lymphocyte count in responding patients. Other authors, in order to limit the possible interaction of other confounding factors, developed a predictive model (iSEND) that included sex, ECOG PS, NLR levels (≥ 5 or < 5), and delta NLR (calculated with NLR at baseline and before the second course of nivolumab) [24], showing that patients within the poor risk group (iSEND poor) were significantly associated with progressive disease. In addition, other authors have evaluated the derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (dNLR), a novel parameter that includes, in addition to absolute neutrophil count, other granulocyte populations, reporting a poorer outcome with nivolumab in patients with high dNLR values (dNLR ≥ 3) [11, 15].

Here, we confirmed, in a large multicenter cohort, the negative predictive role of high baseline NLR (NLR ≥ 5) in patients treated with nivolumab, with a shorter PFS (p = 0.03) and OS (p = 0.001) and a trend towards a decreased DCR (p = 0.06) compared to patients with low baseline NLR levels (NLR < 5). High NLR levels may therefore be the result of an increase in neutrophil-dependent inflammation as well as reduced lymphocyte activity and infiltration, determining a weaker lymphocyte-mediated immune response and subsequent poor response to ICIs [14]. These data suggest that pretreatment evaluation of NLR levels may be useful in the decision-making of unselected patient candidates for second-line therapy in NSCLC.

Baseline platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) levels have been correlated with poor prognosis in several solid tumors, including NSCLC [25]. Recently this hematologic parameter has been evaluated in small retrospective studies also in patients with NSCLC treated with nivolumab. Using different cutoff values (PLR ≥ 160 and ≥ 200, respectively), some authors did not find any statistically significant difference in terms of OS or ORR between patients with NSCLC treated with nivolumab with high pretreatment levels compared with those with low PLR values [11, 14]. In contrast, Diem et al. subdivided patients into three groups, according to PLR tertiles (PLR < 193, PLR 193–328, and PLR > 328), and showed that patients with higher PLR values had worse OS and ORR [26]. Here, we demonstrated that a pretreatment PLR level of 200 or above is associated with a statistically significant worse PFS (p = 0.03) and OS (p = 0.05), as well as a decreased response (p = 0.04) and disease control (p = 0.001) with nivolumab. After multivariate analysis, high NLR and high PLR remained significantly associated with poorer OS (p = 0.005 and p = 0.023, respectively), suggesting that their negative prognostic impact is independent of other clinical variables, such as age, sex, histology, and previous radiotherapy exposure.

Finally, we evaluated the possible correlation between lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels and the outcome of patients treated with nivolumab, dichotomizing our cohort into two subgroups according to LDH values at the UNL or above vs. values below the UNL. LDH is a marker of inflammation and tumor burden in patients with solid tumors. Recently, some authors reported inferior outcomes in patients with NSCLC and high LDH levels treated with nivolumab [15, 16]. However, in the present study we did not find any statistical difference between patients with high vs. low/normal LDH levels in terms of PFS (p = 0.84) or OS (p = 0.582), likely due to the small sample size (pretreated LDH levels available only in 108/187 patients).

We are aware of the limitations of our study. First, the retrospective nature of this analysis that may have introduced potential bias and confounding factors. However, we included all consecutive patients with NSCLC treated with nivolumab, limiting the potential bias of selection inherent in this type of analyses. Second, we included only patients treated with nivolumab for at least four administrations of therapy and at least a radiological evaluation or, in the case of treatment discontinuation for AEs during the first four doses of therapy, at least a radiological evaluation. Therefore, all patients who died before the first disease re-staging were excluded from the study in order to limit other confounding factors that may have contributed to the poor prognosis of these patients and to allow a better characterization of nivolumab efficacy according to clinicopathological characteristics of patients. Finally, the IHC status of PD-L1 was largely unknown (approx. 90%), since PD-L1 testing was not performed as routine clinical practice at the time of treatment of most of the patients included.

Conclusions

These routine available peripheral blood markers of inflammation, if validated in large prospective studies, may be an attractive biomarker that can be easily and quickly integrated into clinical practice, without additional costs, and may help clinical decision-making. In conclusion, patients with pretreated NSCLC and high pretreatment levels of NLR (≥ 5) and PLR (≥ 200) may experience inferior outcomes when treated with nivolumab. Therefore, in this subgroup of patients with poor prognosis the use of alternative therapeutic strategies, such as the combination docetaxel/nintedanib or docetaxel/ramucirumab, may be a valuable option, especially in the case of negative PD-L1 expression and/or the presence of other additional poor prognostic factors (such as high tumor burden, liver and bone metastases, two or more previous lines of therapy, ECOG PS ≥ 1, never smoking status, and oncogene-addicted tumors) [27].

Abbreviations

- AJCC:

-

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- CR:

-

Complete response

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate

- dNLR:

-

Derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemistry

- iSEND:

-

Immunotherapy, sex, ECOG PS, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and delta NLR model

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ORR:

-

Overall response rate

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PD-1:

-

Programmed cell death 1

- PD-L1:

-

Programmed cell death ligand 1

- PD:

-

Progressive disease

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival

- PLR:

-

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- PR:

-

Partial response

- PS:

-

Performance status

- Pts:

-

Patients

- SD:

-

Stable disease

- TNM:

-

Tumor, node, metastasis

- UNL:

-

Upper normal limit

References

Gridelli C, Ascierto PA, Grossi F, et al. Second-line treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer non-oncogene addicted: new treatment algorithm in the era of novel immunotherapy. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2018;13:76–84.

Russo A, Franchina T, Ricciardi GRR, et al. The changing scenario of 1st line therapy in non-oncogene addicted NSCLCs in the era of immunotherapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;130:1–12.

Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–35.

Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1627–39.

Ribas A, Hersey P, Middleton MR, et al. New challenges in endpoints for drug development in advanced melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:336–41.

Vokes EE, Ready N, Felip E, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057): 3-year update and outcomes in patients with liver metastases. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:959–65.

Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim D-W, et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1540–50.

Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823–33.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74.

Bagley SJ, Kothari S, Aggarwal C, et al. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a marker of outcomes in nivolumab-treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2017;106:1–7.

Russo A, Franchina T, Ricciardi GRR, et al. Baseline neutrophilia, derived neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (dNLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), and outcome in non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab or docetaxel. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:6337–43.

Ameratunga M, Chénard-Poirier M, Moreno Candilejo I, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio kinetics in patients with advanced solid tumours on phase I trials of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2018;89:56–63.

Fukui T, Okuma Y, Nakahara Y, et al. Activity of nivolumab and utility of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictive biomarker for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective observational study. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20(208–214):e2.

Zer A, Sung MR, Walia P, et al. Correlation of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and absolute neutrophil count with outcomes with PD-1 axis inhibitors in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(426–434):e1.

Mezquita L, Auclin E, Ferrara R, et al. Association of the lung immune prognostic index with immune checkpoint inhibitor outcomes in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:351–7.

Tanizaki J, Haratani K, Hayashi H, et al. Peripheral blood biomarkers associated with clinical outcome in non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:97–105.

Banna GL, Passiglia F, Colonese F, et al. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: a tool to improve patients’ selection. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;129:27–39.

Kargl J, Busch SE, Yang GHY, et al. Neutrophils dominate the immune cell composition in non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14381.

Sagiv JY, Michaeli J, Assi S, et al. Phenotypic diversity and plasticity in circulating neutrophil subpopulations in cancer. Cell Rep. 2015;10:562–73.

Christoffersson G, Phillipson M. The neutrophil: one cell on many missions or many cells with different agendas? Cell Tissue Res. 2018;371:415–23.

Facchinetti F, Veneziani M, Buti S, et al. Clinical and hematologic parameters address the outcomes of non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Immunotherapy. 2018;10:681–94.

Kiriu T, Yamamoto M, Nagano T, et al. The time-series behavior of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio is useful as a predictive marker in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193018.

Nakaya A, Kurata T, Yoshioka H, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as an early marker of outcomes in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:634–40.

Park W, Kwon D, Saravia D, et al. Developing a predictive model for clinical outcomes of advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with nivolumab. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(280–288):e4.

Gu X, Sun S, Gao X-S, et al. Prognostic value of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in non-small cell lung cancer: evidence from 3430 patients. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23893.

Diem S, Schmid S, Krapf M, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer. 2017;111:176–81.

Peters S, Cappuzzo F, Horn L, et al. OA03.05 analysis of early survival in patients with advanced non-squamous NSCLC treated with nivolumab vs docetaxel in checkmate 057. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:S253.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Alessandro Russo, Marco Russano, Giuseppe Tonini, Daniele Santini, and Vincenzo Adamo contributed to the design of the study; Alessandro Russo, Marco Russano, Tindara Franchina, Maria R. Migliorino, Giuseppe Aprile, Giovanni Mansueto, Alfredo Berruti, Alfredo Falcone, Michele Aieta, Alain Gelibter, Sandro Barni, Michele Maio, Olga Martelli, Francesco Pantano, Daniela Iacono, Lorenzo Calvetti, Silvia Quadrini, Elisa Roca, Enrico Vasile, Marco Imperatori, Mario Occhipinti, Giulia Pasquini, Salvatore Intagliata, Giuseppina R. R. Ricciardi, Giuseppe Tonini, Daniele Santini, and Vincenzo Adamo contributed to the clinical management of patients and database, providing clinical, pathological and molecular data; Alessandro Russo, Marco Russano, Daniele Santini, Vincenzo Adamo performed data analysis and interpretation; Alessandro Russo, Marco Russano, Vincenzo Adamo, and Daniele Santini wrote the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The trial protocol was previously approved by the Ethics Committee of the coordinating Center (Campus Bio-Medico University of Rome) on 2 March 2018 (approval n. 23/18 OSS ComEt CBM) and all the patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosures

All named authors (Alessandro Russo, Marco Russano, Tindara Franchina, Maria R Migliorino, Giuseppe Aprile, Giovanni Mansueto, Alfredo Berruti, Alfredo Falcone, Michele Aieta, Alain Gelibter, Antonio Russo, Sandro Barni, Michele Maio, Olga Martelli, Francesco Pantano, Daniela Iacono, Lorenzo Calvetti, Silvia Quadrini, Elisa Roca, Enrico Vasile, Marco Imperatori, Mario Occhipinti, Antonio Galvano, Fausto Petrelli, Luana Calabrò, Giulia Pasquini, Salvatore Intagliata, Giuseppina R.R. Ricciardi, Giuseppe Tonini, Daniele Santini, Vincenzo Adamo) have nothing to disclose.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Prof. Vincenzo Adamo, upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11550561.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Russo, A., Russano, M., Franchina, T. et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR), Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR), and Outcomes with Nivolumab in Pretreated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC): A Large Retrospective Multicenter Study. Adv Ther 37, 1145–1155 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01229-w

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01229-w