Abstract

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is commonly encountered in eye clinics and hospitals, and it is therefore very important to understand DED prevalence in outpatients.

Methods

A multicenter, hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted among outpatients in Japan to ascertain DED prevalence and relationships between DED and patient profiles, including eye disease, DED diagnosis history, and surgical history. DED was diagnosed according to diagnostic criteria of the Asia Dry Eye Society. Patient self-assessment of DED-related subjective symptoms was conducted using the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5). Tear break-up time was evaluated in subjective symptom-positive patients.

Results

The prevalence of DED was 55.7% in 990 patients (mean age 69.1 ± 13.4 years), DED was commonly experienced in combination with other ocular diseases. In revisiting patients, 15.2% had not previously been diagnosed as DED, and their total DEQ-5 scores were higher than those of patients who had undergone DED treatment.

Conclusion

This study revealed that more than half of the outpatients had DED. Among revisiting patients, there were many “hidden” DED patients who had not been diagnosed with DED in the past. There is a high likelihood of finding DED comorbidity in patients with other eye diseases in eye clinics and hospitals.

Funding

Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Trial Registration

UMIN Clinical Trials Registry Identifier, UMIN000035506.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Dry eye disease (DED) is commonly encountered in eye clinics and hospitals and it is therefore very important to understand the DED prevalence in outpatients. |

We investigated the DED prevalence in outpatients of eye clinics and an eye hospital in Japan. |

In addition, the relationships between DED and background information of the patients, including other eye diseases, DED diagnosis history and surgical history were examined. |

What was learned from the study? |

More than half of the outpatients had DED. |

The patients with allergic conjunctivitis and patients after vitreoretinal surgery had the highest prevalence of DED. |

Among revisiting patients, there were many hidden DED patients who had not been diagnosed with DED in the past. |

Introduction

Dry eye disease (DED) is defined by the Asia Dry Eye Society as follows: DED is a multifactorial disease characterized by unstable tear film, causing subjective symptoms such as dryness and eye discomfort and/or accompanied by ocular surface damage [1]. Unstable tear film impairs visual function [2, 3], affecting the quality of vision and/or life in DED patients [4]. Also, work productivity was reduced in the DED group in comparison with the non-DED group [5]. As DED influences the daily life of the patients and is associated with work productivity loss, patients should be accurately diagnosed and treated.

Many epidemiological reports with respect to DED have been published worldwide, showing the prevalence of DED ranging from 6.8 to 61.57% [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. This broad range in prevalence may be attributed to differences in race, age, and gender proportions in the study population, and the diagnostic criteria also impact the results. Regarding the racial differences, Hispanic and Asian women have more severe DED symptoms than Caucasians [14].

DED is associated with other eye diseases and treatments, for example, glaucoma. In patients with normal tension glaucoma (NTG) who topically received prostaglandin analog monotherapy for 1 year or longer, the ocular surface disease index and fluorescein keratoconjunctival staining score were significantly higher than those in normal subjects [15]. In cataract patients with no complications before cataract surgery, the incidence of DED 7 days after phacoemulsification was 9.8% [16]. It is known that short tear break-up time (TBUT)-type DED is a major subtype, as is the aqueous-deficient type in Japan [17, 18], and this subtype is associated with allergic conjunctivitis [19]. Some subjective symptoms in allergic conjunctivitis overlap with those in DED. This may lead to misdiagnosis of DED, and for DED cases to be overlooked. Taken together, it is important to pay attention to the symptoms and medical history of eye diseases and treatments in the diagnosis of eye disease. Some dry eye prevalence surveys have been conducted in eye clinic outpatients [8, 13, 20,21,22]; however, there has been no study to examine the DED prevalence in patients with other eye diseases and history of eye surgery. Also, there has been no study to examine the “hidden” DED patient who had not been diagnosed with DED.

The purpose of this study was to ascertain DED prevalence in outpatients of eye clinics and an eye hospital in Japan. In addition, the relationships between DED and background information of the patients, including other eye diseases, DED diagnosis history, surgical history, and other characteristics was examined.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a multicenter, hospital-based cross-sectional study carried out at 6 eye clinics [Fujita Eye Clinic (Tokushima, Japan), Sakka Eye Clinic (Fukuoka, Japan), Kasai Eye Clinic (Tokyo, Japan), Kakinoki Eye Clinic (Tokyo, Japan), Abe Eye Clinic (Oita, Japan), Sapporo Kato Eye Clinic (Hokkaido, Japan)] and one eye hospital [(Heisei Eye Hospital (Miyagi, Japan)]. All patients were given a full explanation about this study and provided written informed consent. This study followed the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Ethics Committee of Medical Corporation TOUKEIKAI Kitamachi Clinic (Tokyo, Japan), approved the protocol prospectively (ethical approval No. STS06238, date: 18 December 2018). The study was registered with UMIN-CTR (http://www.umin.ac.jp/, Identification no. UMIN000035506).

Patients

This study was conducted among outpatients who visited the study sites. The outpatients were over 20 years of age and were consecutively enrolled. The recruitment of subjects was conducted from January to April 2019. Outpatients who could not perform fluorescein staining for safety reasons, such as hypersensitivity, were excluded from the study. Also, patients wearing contact lenses on a visiting day of the study were excluded. The sample size of this study was calculated to include a sufficient number of patients (50 patients) with allergic conjunctivitis which had been reported to be associated with DED. Assuming the prevalence of allergic conjunctivitis of 5% and a combination with dry eye of 20%, the sample size was determined to be 1000 patients.

Patient Background

The patients’ background information was collected from their medical records. Data collected were on sex, age, first visit/return visit, DED treatment, daily contact lens wearing, eye diseases on the study day, DED diagnosis history in the past 2 years, and eye surgery history in the past 1 year. All their information on multiple eye diseases and surgery history were also collected.

Questionnaire for DED-Related Subjective Symptoms

DED-related symptoms were evaluated using the 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire (DEQ-5, including eye discomfort, dryness, and watery eyes), which was translated into Japanese [23]. In addition, the presence or absence of the following 12 symptoms associated with DED was also confirmed at the same time as evaluation using DEQ-5: eye fatigue, eye pain, eye discharge, foreign body sensation, watery eyes, blurred vision, itchy eye, heaviness, red eye, eye discomfort, dryness, and photophobia [24]. The criterion for dry eye screening was DEQ-5 total score ≥ 6 as symptom-positive.

Ocular Surface Examination

In subjects with DED-related symptoms, the ocular surface was examined using a fluorescein examination test paper (Ayumi Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan). A fluorescein strip moistened with saline was applied to the rim of the lower eyelid and staining was performed with a minimal amount of dye. The TBUT was measured three times consecutively, and the average value was evaluated as ≤ 5 s or > 5 s. The fluorescein staining score (FSS) of the cornea and conjunctiva was then evaluated in three areas (temporal bulbar conjunctiva, nasal bulbar conjunctiva, and cornea), scored on a 0- to 3-point scale (from 0, no damage, to 3, damage over the entire area), and then totaled (maximum = 9 points). Total score was evaluated as < 3 or ≥ 3.

Diagnostic Criteria and Definition of DED

The Asia Dry Eye Society criteria were used to diagnose DED, and subjects who met both DED symptom-positive status (DEQ-5 total score ≥ 6) and TBUT ≤ 5 s were diagnosed as DED [1]. Also, patients who had a DED history in the past 2 years were defined as DED. The newly diagnosed DED patients who had not been diagnosed with DED in the past 2 years were defined as hidden DED patients.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) or IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and other tests by RPM (Tokyo, Japan) and KONDO Photo Process (Osaka, Japan). Welch’s t test was performed for comparisons between two groups. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis was used to calculate the cutoff values of the number symptoms among the 12 DED-related subjective symptoms between patients who met the DED diagnostic criteria and patients who did not. p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Subjects

In this study, 1011 outpatients were enrolled. Among them, 990 subjects, who completed the DEQ-5 and underwent the prescribed TBUT measurement, were analyzed. The characteristics of the study patients are summarized in Table 1. The number of patients over the age of 60 accounted for more than 80% of this population. More than half of the patients were women, and most were return visitors.

Prevalence of DED, Proportion of DED Patients with Epithelial Disorder

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of DED in outpatients of eye clinics and an eye hospital in Japan. The prevalence of DED (Asia Dry Eye Society diagnostic criteria positive, or with DED history in the past 2 years) was 55.7% in this study. The prevalence of DED with Asia Dry Eye Society diagnostic criteria positive only was 37.0% overall (data not shown). The prevalence of DED in first-visiting patients was lower than that of revisiting patients.

Prevalence of dry eye disease in outpatients of eye clinics and an eye hospital in Japan. Blue dry eye disease: patients who had been diagnosed with dry eye disease in the past 2 years or with tear break-up time < 5 s and with a total score of 5-Item Dry Eye Questionnaire > 6; gray non-dry eye disease: patients other than the above

Table 2 shows the proportion with epithelial disorder. DED patients without epithelial disorder (FSS score < 3) accounted for more than 80%. The scores were similar between the first visit and the return visit.

Prevalence of DED for Each Patient Background Characteristic

Table 3 shows the prevalence of DED in patients with other eye diseases or after eye surgery. The patients with allergic conjunctivitis and patients after vitreoretinal surgery had the highest prevalence of DED. The prevalence of DED also exceeded 50% in many other patient background characteristics.

Hidden DED Patients at Return Visit

Figure 2 shows the proportion of DED patients who had not previously been diagnosed among revisiting patients. In revisiting patients, 15.2% were the newly diagnosed DED patients who had not been diagnosed with DED in the past 2 years (hidden DED patients). The hidden DED patients had the highest proportion of allergic conjunctivitis, but the condition was uniformly present across all patient background characteristics.

Proportion of dry eye disease patients who had not been diagnosed previously among revisiting patients. Blue dry eye disease patients who had been diagnosed with dry eye disease in the past 2 years; red dry eye disease patients who had not been diagnosed with dry eye disease in the past 2 years; gray non-dry eye disease patients, After cataract surgery more than a month had passed since surgery

Subjective Symptoms and TBUT Between DED Patients with Treatment and Hidden DED Patients

Table 4 shows the total score of DEQ-5 and the number of symptoms among 12 DED-related subjective symptoms in the revisiting patients with DED treatment and the hidden DED patients. In the background of all patients except allergic conjunctivitis patients, the total DEQ-5 scores of the patients with DED treatment were significantly lower than those of the hidden DED patients (p < 0.001, Welch’s t test). The number of subjective symptoms in patients with DED treatment was also significantly lower in comparison with that of hidden DED patients (p < 0.001, Welch’s t test).

Table 5 shows the proportion of patients with TBUT ≤ 5 s in the revisiting patients with DED treatment and the hidden DED patients. The proportion of patients with TBUT ≤ 5 s among the hidden DED patients was not included in the 95% CI of the treatment group.

Distribution of 12 DED-Related Subjective Symptoms in DED and Non-DED Patients

Table 6 shows the differences in the 12 DED-related subjective symptom distributions in DED and non-DED patients, in which DED was Asia Dry Eye Society diagnostic criteria positive only. The subjective symptoms that had the most difference between DED and non-DED were dryness and eye discomfort, which were included in the DEQ-5. On the other hand, although watery eyes was one of the subjective symptoms included in the DEQ-5, it showed the smallest difference between DED and non-DED patients. Among the subjective symptoms not included in DEQ-5, those with large differences between DED and non-DED patients were eye fatigue and foreign-body sensation.

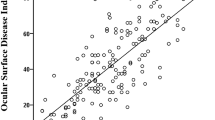

Figure 3 shows the patient distribution for 12 DED-related subjective symptoms in patients who met the DED diagnostic criteria and patients who did not, in which DED was Asia Dry Eye Society diagnostic criteria positive only. DED patients had more subjective symptoms than non-DED patients. The average number and standard deviation of symptoms in DED patients (n = 367) was 6.9 ± 2.4, and that in non-DED (n = 623) was 3.55 ± 2.6. The number of symptoms was were significantly different between DED and non-DED patients (p < 0.001, Welch’s t test). The cutoff value of the number of symptoms among 12 DED-related subjective symptoms between DED and non-DED was 5 (area under the curve = 0.823, ROC analysis).

The patient distribution for 12 dry eye disease-related subjective symptoms in dry eye disease and non-dry eye disease patients. Blue dry eye disease patients: Patients with tear break-up time ≤ 5 s and with a total score of DEQ-5 ≥ 6, n = 367; gray non-dry eye disease patients: Patients other than the above, n = 623. The 12 dry eye disease-related subjective symptoms were eye fatigue, eye pain, eye discharge, foreign body sensation, watery eyes, blurred vision, itchy eye, heaviness, red eye, eye discomfort, dryness, and photophobia

Discussion

Prevalence of DED

In this multicenter, hospital-based cross-sectional study, we assessed the prevalence of DED in outpatients who were seen in six eye clinics and an eye hospital in Japan. Multiple DED prevalence surveys for outpatients have been conducted in the past, and the DED prevalence has been reported as 7.99–61.57% [8, 13, 20,21,22]. The surveyed areas of these reports were Asia (Japan, China, India) and Africa (Nigeria). Among them, in the previous report in Japan [22], dry eye diagnosis was determined in terms of the presence or absence of dry eye treatment and necessity for eye drop treatment, and the prevalence rate was 26.3%. The prevalence of DED in the present study was 55.7% (Fig. 1), higher than in the previous surveys. The difference in reported prevalence may be attributable to the difference in DED criteria, or the timing of conduction of the survey, as the current study was conducted in the winter to spring season. Ophthalmologists may encounter dry eye patients very frequently among outpatients of eye clinics and hospitals in Japan, and need to be aware as to whether any patients have dry eye.

Hidden DED Patients

In this study, 15.2% of the revisiting outpatients were the hidden DED patients (Fig. 2). The hidden DED patients were found as a result of consecutively performing dry eye diagnosis in this study. The hidden DED patients were those patients who had a sufficient degree and frequency of subjective symptoms, as DEQ-5 total score ≥ 6. It is an important problem that such obvious DED cases were missed among 10% of revisiting patients.

There may be multiple reasons why these patients were not recognized as DED. One of the reasons is the difficulty in differentiating DED from other eye diseases. Another is that the prioritization of the treatment of diseases with high blindness rates may have diminished awareness that an ophthalmologist would suspect these patients to have associated DED. Blindness by DED is very rare. However, DED is a disease that lowers the quality of life (QOL) as seriously as does angina [25], affects sleep [26], and reduces labor productivity [5]. Detection and treatment of DED can be expected to improve patients’ QOL. In this study, the total DEQ-5 score and the number of 12 DED-related subjective symptoms of the patients with DED treatment was significantly lower than those of the hidden DED patients (p < 0.001, Welch’s t test; Table 4), and the proportion of patients with TBUT < 5 s was also lower. These results suggest that DED treatment for the hidden DED patients may improve their subjective symptoms and TBUT.

Prevalence of DED for Each Patient Background Characteristic

DED is a multifactorial disease characterized by unstable tear film, and may be accompanied by ocular surface damage. Many eye diseases with ocular surface disorders are known besides DED. The ocular surface disorders may also be caused by eye treatments. It is conceivable that the mechanism by which these eye diseases and treatments cause ocular surface disorders coincides with the mechanism by which DED develops. The presence of other ocular surface diseases or topical treatments may exacerbate DED condition. For example, allergic conjunctivitis is an inflammatory disease of the conjunctiva in which a type I allergic reaction is involved, and is a disease accompanied by ocular findings such as subjective symptoms and hyperemia, and its relevance to dry eye has been reported [19]. In patients with NTG who received topical prostaglandin analog monotherapy for 1 year or longer, OSDI and fluorescein keratocorneal conjunctival staining scores were significantly higher than in normal subjects [15]. In patients after cataract surgery and retinal vitreous surgery, it has been reported that conjunctival goblet cell counts were lower [27, 28] and that TBUT was shortened [28, 29]. In the present study, DED patients were found among more than half of patients with allergic conjunctivitis, glaucoma, retinal disease, after cataract surgery, and after retinal vitrectomy (Table 3). More caution in regard to DED complications should be heeded for the patients with these patient background characteristics. The results of this study are considered to support the above published reports.

DED-Related Subjective Symptoms

The evaluation of DED subjective symptoms is an important step in DED diagnosis. There are great differences between individuals in the expression of subjective symptoms. Questionnaires make it possible to objectively evaluate subjective symptoms. In this study, we evaluated subjective symptoms with DEQ-5 and the presence or absence of 12 symptoms. The DEQ-5 is a very simple questionnaire, with only five questions. DEQ-5 made it possible to evaluate to the subjective symptoms of more than 1000 patients within a limited time of outpatient care, and to diagnose DED. The evaluation of 12 DED-related subjective symptoms was useful in studying the characteristics of subjective symptoms of DED patients. The results of this study revealed that, in DED diagnosis, it may be necessary to pay attention to subjective symptoms such as dryness, eye discomfort, eye fatigue, and foreign-body sensation (Table 6).

Limitations

This study had several limitations. There is an inherent selection bias since only patients visiting six eye clinics and one eye hospital were included, and therefore it is not truly an epidemiological study of the prevalence of DED in the general population. This is especially true since the study cohort included postoperative patients. This may explain the reason for the high prevalence relative to previous published studies. We selected the seven study sites from all over Japan. However, the possible existence of selection bias in the study site selection cannot be denied. The “history of DED in the past 2 years” criteria were not based on standardized diagnostic criteria across study sites. The “patients who had not been diagnosed with DED in the past 2 years” and those “diagnosed with DED in this study” may include patients who developed DED between the time of the last visit and the time of the present visit in this study. The present study was conducted from winter to spring; DED is a disease for which the prevalence is affected by the season. It is necessary to investigate the DED prevalence at other seasons or throughout the year. In this study, there were differences in the number of patients with other eye diseases and postoperative patients. By examining the prevalence of DED with the same number of these patients, it will be possible to examine the relationship with DED in more detail.

Conclusions

More than half of the outpatients had DED, and most DED cases were short TBUT-type dry eye. Patients with allergic conjunctivitis and patients after vitreoretinal surgery had the highest prevalence of DED. Among revisiting patients, there were many hidden DED patients who had not been diagnosed with DED in the past. There is a high likelihood of finding DED comorbidity in patients with other eye diseases in eye clinics and hospitals.

References

Tsubota K, Yokoi N, Shimazaki J, et al. New perspectives on dry eye definition and diagnosis: a consensus report by the Asia dry eye society. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:65–76.

Ridder WH 3rd, Zhang Y, Huang JF. Evaluation of reading speed and contrast sensitivity in dry eye disease. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90:37–44.

Goto E, Yagi Y, Matsumoto Y, Tsubota K. Impaired functional visual acuity of dry eye patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:181–6.

Miljanović B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, Schaumberg DA. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:409–15.

Uchino M, Uchino Y, Dogru M, et al. Dry eye disease and work productivity loss in visual display users: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157:294–300.

Farrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IÖ, Schaumberg DA. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:90–8.

Castro JS, Selegatto IB, Castro RS, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of self-reported dry eye in Brazil using a short symptom questionnaire. Sci Rep. 2018;8:2076.

Titiyal JS, Falera RC, Kaur M, Sharma V, Sharma N. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease in North India: ocular surface disease index-based cross-sectional hospital study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018;66:207–11.

Ferrero A, Alassane S, Binquet C, et al. Dry eye disease in the elderly in a French population-based study (the Montrachet study: maculopathy, optic nerve, nuTRition, neurovAsCular and HEarT diseases): prevalence and associated factors. Ocul Surf. 2018;16:112–9.

Arita R, Mizoguchi T, Kawashima M et al. Meibomian gland dysfunction and dry eye are similar, but different based on a population-based study (Hirado-Takushima study) in Japan. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019 (accepted; in press).

Caffery B, Srinivasan S, Reaume CJ, et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease in Ontario, Canada: a population-based survey. Ocul Surf. 2019;17:526–31.

Yasir ZH, Chauhan D, Khandekar R, Souru C, Varghese S. Prevalence and determinants of dry eye disease among 40 years and older population of Riyadh (except capital), Saudi Arabia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2019;26:27–32.

Yu D, Deng Q, Wang J, et al. Air pollutants are associated with dry eye disease in urban ophthalmic outpatients: a prevalence study in China. J Transl Med. 2019;17:46.

Schaumberg DA, Sullivan DA, Buring JE, Dana MR. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:318–26.

Lee TH, Sung MS, Heo H, Park SW. Association between meibomian gland dysfunction and compliance of topical prostaglandin analogs in patients with normal tension glaucoma. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191398.

Kasetsuwan N, Satitpitakul V, Changul T, Jariyakosol S. Incidence and pattern of dry eye after cataract surgery. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78657.

Uchino M, Yokoi N, Uchino Y, et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease and its risk factors in visual display terminal users: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156:759–66.

Yokoi N, Uchino M, Uchino Y, et al. Importance of tear film instability in dry eye disease in office workers using visual display terminals: the Osaka study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159:748–54.

Toda I, Shimazaki J, Tsubota K. Dry eye with only decreased tear break-up time is sometimes associated with allergic conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:302–9.

Onwubiko SN, Eze BI, Udeh NN, Arinze OC, Onwasigwe EN, Umeh RE. Dry eye disease: prevalence, distribution and determinants in a hospital-based population. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2014;37:157–61.

Li J, Zheng K, Deng Z, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of dry eye disease among a hospital-based population in southeast China. Eye Contact Lens. 2015;41:44–50.

Ayaki M, Kawashima M, Uchino M, Tsubota K, Negishi K. Possible association between subtypes of dry eye disease and seasonal variation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;11:1769–75.

Chalmers RL, Begley CG, Caffery B. Validation of the 5-item dry eye questionnaire (DEQ-5): discrimination across self-assessed severity and aqueous tear deficient dry eye diagnoses. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33:55–60.

Toda I, Fujishima H, Tsubota K. Ocular fatigue is the major symptom of dry eye. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1993;71:347–52.

Schiffman RM, Walt JG, Jacobsen G, Doyle JJ, Lebovics G, Sumner W. Utility assessment among patients with dry eye disease. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1412–9.

Kawashima M, Uchino M, Yokoi N, et al. The association of sleep quality with dry eye disease: the Osaka study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2016;10:1015–21.

Heimann H, Coupland SE, Gochman R, Hellmich M, Foerster MH. Alterations in expression of mucin, tenascin-c and syndecan-1 in the conjunctiva following retinal surgery and plaque radiotherapy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;239:488–95.

Oh T, Jung Y, Chang D, Kim J, Kim H. Changes in the tear film and ocular surface after cataract surgery. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56:113–8.

Lee JH, Na KS, Kim TK, Oh HY, Lee MY. Effects on ocular discomfort and tear film dynamics of suturing 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomies. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2019;82:214–9.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants for their participation and staff of the Fujita Eye Clinic (Tokushima, Japan), Sakka Eye Clinic (Fukuoka, Japan), Kasai Eye Clinic (Tokyo, Japan), Kakinoki Eye Clinic (Tokyo, Japan), Abe Eye Clinic (Oita, Japan), Sapporo Kato Eye Clinic (Hokkaido, Japan), and Heisei Eye hospital (Miyagi, Japan). We also would like to thank RPM Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and KONDO Photo Process Co., Ltd. (Osaka, Japan) for their assistance in data management and statistical analysis.

Funding

This study and publication charges were funded by Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Authorship Contribution

Conceptualization, Jun Shimazaki., Hirotsugu Kishimoto and Yoshiaki Yamada; Methodology, Jun Shimazaki., Hirotsugu Kishimoto and Yoshiaki Yamada; Investigation, Yuya Nomura, Shinichiro Numa, Yoko Murase, Kazukuni Kakinoki, Fumihide Abe, Yuji Kato, and Hitoshi Okabe; Project administration, Hirotsuga Kishimoto and Yoshiaki Yamada; Resources, Yuya Nomura, Shinichiro Numa, Yoko Murase, Kazukuni Kakinoki, Fumihide Abe, Yuji Kato, and Hitoshi Okabe; supervision, Jun Shimazaki; Writing—original draft preparation, Yoshiaki Yamada; Writing—review & editing, Jun Shimazaki., Hirotsugu Kishimoto.

Disclosures

Jun Shimazaki has received consulting fees from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. about this work. Jun Shimazaki has received consulting fees from QD Laser, Inc., and IDD Inc. outside this work. Jun Shimazaki has received honoraria from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Alcon Pharmaceuticals Ltd. outside this work. Yuya Nomura has received consulting fees from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. outside this work. Shinichiro Numa has received consulting fees from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Kowa Company, Ltd. outside this work. Yuji Kato has received consulting fees, and honoraria from Santen outside this work. Hitoshi Okabe has received consulting fees from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and honoraria from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Sucampo Pharmaceutical Inc., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Alcon Japan Ltd., Kowa Company, Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., Senju Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Nitten Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. outside this work. Hitoshi Okabe is an employee at Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Yoko Murase, Kazukuni Kakinoki, and Fumihide Abe declare no conflict of interest. Yoshiaki Yamada is an employee at Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The funders had no role in the collection, analyses. All facilities have received a grant from Santen towards this work. The following facilities have received grants from Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. outside this work: Department of Ophthalmology, Tokyo Dental College, Ichikawa General Hospital, wherein Jun Shimazaki is the director; Sakka Eye Clinic, wherein Shinichiro Numa is the director; Kakinoki Eye Clinic, wherein Shinichiro Numa is the director; Abe Eye Clinic, wherein Fumihide Abe is the director; Sapporo Kato Eye Clinic, wherein Yuji Kato is the director, and Heisei Eye Hospital, wherein Hitoshi Okabe is the director. Department of Ophthalmology, Tokyo Dental College, Ichikawa General Hospital has received grants from HOYA corporation outside this work. Abe Eye Clinic has received grants from Wakamoto Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. outside this work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study protocol was approved by The Ethics Committee of Medical Corporation TOUKEIKAI Kitamachi Clinic (Tokyo, Japan). This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki, and Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research involving Human Subjects in Japan. The subjects received a full explanation of the procedures and provided their written informed consent for participation prior to inclusion in the study. The study was registered in the public registration system (University Hospital Medical Information Network: UMIN (registries no. UMIN000035506)).

Data Availability

The data sets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10008401.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shimazaki, J., Nomura, Y., Numa, S. et al. Prospective, Multicenter, Cross-Sectional Survey on Dry Eye Disease in Japan. Adv Ther 37, 316–328 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01143-w

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01143-w