Abstract

Introduction

Bone metastasis is the most common cause of cancer-related pain, and metastatic bone pain (MBP) is not only severe but also progressive in many patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between pain management and performance status in patients with metastatic bone cancer in the Spanish clinical setting.

Methods

A 3-month follow-up prospective, epidemiologic, multicenter study was conducted in 579 patients to assess the evolution of their performance, the impact of pain control on sleep and functionality, and the degree of pain control according to analgesic treatment.

Results

In patients with MBP, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status (1.5 ± 0.7–1.3 ± 0.7 and 1.3 ± 0.8; p < 0.001) and pain (6.5 ± 1.4–2.8 ± 1.9 and 2.1 ± 1.9; p < 0.001) improved significantly from baseline to months 1 and 3, as did functionality and sleep, after a treatment change consisting of increasing the administration of opioids. Evolution of ECOG and pain were closely related. ECOG and pain outcomes were significantly more favorable in patients treated with opioids versus non-opioid treatment, and in patients who did not need rescue medication versus those who did.

Conclusions

MBP is currently poorly managed in Spain. ECOG improvement is closely and directly related to pain management in MBP. Opioid treatment and a lack of requirements for rescue medication are associated with better ECOG and pain outcomes in MBP patients.

Funding

Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals S.L.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bone metastasis is the most common cause of cancer-related pain [1, 2], and metastatic bone pain (MBP) is not only severe but also progressive in many patients [3]. As the tumor grows and tumor-induced bone remodeling progresses, skeletal-related events (SREs) occur. These include not only pain and “breakthrough pain” but also hypercalcemia, anemia, skeletal fractures, compression of the spinal cord, and decreased mobility and activity [4], all of which compromise the patient’s functional status, quality of life, and survival [5]. Furthermore, chronic pain is frequently associated with anxiety, depression and sleep disorders [6]. All these comorbidities have a negative impact on response to analgesic treatment, which in turn contributes to loss of quality of life. Hence, pain treatment is crucial for these patients [7].

As MBP responds poorly to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), the WHO therapeutic guidelines for cancer pain recommend opioids [8]. These include drugs such as oxycodone, which is effective for pain relief in patients with bone metastases [3] and has a specific effect on neuropathic pain [9], a frequent complication in vertebrae metastases [3]. Other therapies are currently used for MBP: surgical therapy [3], palliative radiotherapy, and radiopharmaceuticals [10, 11]; bisphosphonates, which delay the onset and reduce the risk of SREs in patients with bone metastases [12]; denosumab, which is a fully monoclonal antibody recently approved for the prevention of SREs [13]; and rescue medication, i.e., supplemental analgesia for “breakthrough pain” [14].

We studied the association of pain management with evolution of overall Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status in cancer patients with bone metastases, plus the degree of pain control according to analgesic treatment, to determine the quality of MBP management in the Spanish clinical setting.

Methods

Study Design

This was a 3-month, observational, prospective, multicenter study performed in Spain according to the principles of the revised Declaration of Helsinki in 2013. The protocol was approved by the ethics committee (Comité Ético de Investigación Clínica Regional del Principado de Asturias), and patients provided informed consent before inclusion in the study.

Eligible patients were ≥18 years old and diagnosed with cancer with bone metastases, with a life expectancy ≥3 months and pain intensity ≥4 on a numerical rating scale (NRS). Patients were excluded if they were scheduled for palliative surgery or the investigator considered them to have insufficient cognitive capacity to understand the study.

Outcome Measures

The primary endpoint of this study was to assess the correlation between pain relief and performance status of oncologic patients with bone metastases. Secondary endpoints were to assess the effect of pain control on sleep quality and functionality, as well as pain relief depending on the type of treatment. Basic demographic variables were collected at baseline, along with clinical variables. Patient-reported outcomes were collected at baseline and at months 1 and 3 during the study follow-up, including pain severity and the effect of pain control on sleep and functionality recorded on a 0–10 NRS. Performance status was evaluated at baseline and at months 1 and 3, and rated according to the ECOG scale.

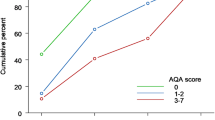

The correlation between ECOG (measured by the change in performance status score and by the proportion of patients with better/stable/worse ECOG compared with baseline) and pain (measured by five pain parameters: (1) degree of change; (2) patients with improved/stable/worsened pain; (3) those with ≥20% of pain improvement; (4) those with ≥50% of pain improvement; and (5) those ending with a NRS ≤ 3) was also assessed.

Statistical Analysis

Statistically significant differences for ECOG, pain, functionality, and sleep between baseline and months 1 and 3 were determined using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The influence of pain management on ECOG during follow-up was assessed using the Spearman correlation, Kruskal–Wallis test and the Chi-Square test.

Results

Evolution of ECOG, Pain, Functionality, and Sleep

Overall, 579 patients (mean age 63.2 years; 53.2% male) were included in this study across 56 centers in Spain by October 1, 2010 (Table 1). The patients were sampled sequentially to avoid bias during patient selection. In these patients, performance status, pain, functionality, and sleep improved significantly over the study (Table 2). The correlation between the change in ECOG and pain was significant (p < 0.001), with significant improvements in pain and ECOG outcomes both observed at month 1. All patients with ECOG improvement over baseline also had a better evaluation of pain: most patients with stable ECOG also showed stable pain (75%), and most patients with worse ECOG over baseline also showed worse pain (77%; data not shown).

Treatments

As shown in Table 2, seven different treatment modalities were used during the study. Chemotherapy was indicated in 68% of patients before the study: as first line in nearly half of these (43.4%), second line in 20.4%, and third or more lines in 18%. Most common therapies used were vinorelbine (11.7%), cisplatin (11.7%), carboplatin (11.4%), gemcitabine (10.7%) and taxotere (10.4%).

Mean doses of the four most frequent opioids used were: fentanyl 56.6 μg/h every 3 days; tramadol 101.7 mg every 8 or 12 h; oxycodone 22.1 mg every 12 h and morphine 46 mg every 12 h.

Bisphosphonates, almost exclusively zoledronic acid (96.7%), were received by 51.7% of patients before the study. Palliative radiotherapy to alleviate pain was given to 20.9%, with the spinal column being the most frequent application area (56.2%), followed by pelvis (30.6%) and femur (10.7%). Median dose was 30 Gy, with 10× 300 cGy in 57.9% of cases (data not shown). Finally, surgery and non-pharmacological treatment were considered for 4.1% and 0.7% of patients before the study, respectively.

Change in Treatment During Follow-Up

Chemotherapy and bisphosphonates remained stable over the study, and had no effect on ECOG and pain (p = 0.801 and p = 0.172; and p = 0.462 and p = 0470, respectively); however, there was an increase in palliative radiotherapy at baseline and a decrease at the following months, with no effect on ECOG or pain (p = 0.321 and p = 0.715; Table 2).

Non-opioids or coadjuvant administration decreased over the study, while opioids almost doubled at baseline and remained at the same high levels thereafter (Table 2). Mean doses of fentanyl and oxycodone increased slightly from 56 to 62 μg/h and 22 to 25 mg, respectively.

Rescue treatment was prescribed in 71.4% of patients at baseline (immediate release [IR] oxycodone capsules 60.4%, IR oxycodone solution 11.7%, morphine 13.8%, fentanyl 7.5%, and others 6.6%) and in 44.4% at month 1 (mainly oxycodone 66.8% or morphine 16%) and in a significantly smaller proportion of patients at month 3 (35%; p = 0.001). Laxatives and antiemetics were prescribed in 71.5% and 54.7% of patients, respectively, at baseline and in 71.8% and 44.4%, respectively, at month 1. Treatment at month 3 was similar to the treatment received at month 1.

Treatment compliance was high at the 1- and 3-month visits. At month 1, 76.5% of patients complied with radiotherapy, 92.6% with chemotherapy, 86.8% with bisphosphonates, and 95.3% with analgesic medication. At month 3, percentages were: radiotherapy 79.5%, chemotherapy 86.5%, bisphosphonates 79.9% and analgesic medication 93.2%.

Regarding adverse events (AE) to analgesic treatment, 37 (6.4%) patients experienced some baseline AEs, 53 (9.8%) patients had AEs at month 1, and 44 (9.3%) patients had AEs at month 3. The most frequent AEs, for the first and third months, were constipation (27.4% and 36.5%), nausea (23.8% and 19.5%), and somnolence (12.3% and 14.6%), respectively (Supplementary Figure 1). There were no grade 4 AEs, six patients were grade 3 (15.8%), with opioids AEs being the most common.

ECOG Evolution According to Treatment

Patients treated with a specific analgesic treatment (prescribed at baseline and with confirmed compliance at the specific time point analyzed) were compared with those who did not receive it in terms of ECOG. At both time points, patients treated with opioids showed significantly more favorable ECOG outcomes than those who did not (p < 0.001). Similarly, patients who did not need rescue medication showed more favorable ECOG outcomes than those who did (p < 0.001; Table 3).

Pain Evolution According to Treatment

The pain parameters of patients treated with a specific analgesic treatment (prescribed at baseline and with confirmed compliance at the specific analyzed time point) were compared with those that did not. Opioids and rescue medication showed significant differences depending on whether they were used or not. Since opioids seemed to have an effect on pain evolution, the two most commonly used (oxycodone and fentanyl) were analyzed specifically (Table 4).

At month 1, there was a significant difference in pain between patients taking and not taking opioids. Similarly, there were significant differences in all pain parameters in favor of patients not taking rescue medication. Mean decrease in pain (−3.9 vs. −3.2; p = 0.003) and the proportion of patients with ≥50% improvement in pain (72.9% vs. 59.3%; p = 0.007) were significantly larger in patients taking oxycodone than in those taking other opioids. The proportion of patients with ≥50% improvement in pain was significantly lower in patients taking fentanyl than in those taking other opioids (59.1% vs. 71.5%; p = 0.041).

After 3 months, mean reduction in pain was significantly greater in patients treated with opioids (−4.4 vs. −3.6; p = 0.014). Mean decrease in pain, and the proportion of patients with ≥20% improvement, ≥50% improvement, and those ending with NRS ≤ 3 were significantly in favor of patients not taking rescue medication. Mean decrease in pain (−4.7 vs. −3.6; p < 0.001) and the proportion of patients with ≥50% improvement (84.6% vs. 71.3%; p = 0.002) were significantly larger in patients taking oxycodone than in those taking other opioids. In terms of fentanyl, 83% of patients taking this drug decreased pain by ≥20%, and 66% by ≥50% vs. 93.2% (p = 0.015) and 83.1% (p = 0.005) of patients taking other opioids, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

Good management of bone metastases has been shown to considerably relieve pain [7]. However, while baseline pain values in this study (mean NRS = 6.5) were moderate–severe, and up to 43.5% of patients had neuropathic pain, which is difficult to treat [15], only 59% of patients were being treated with opioids. The WHO analgesic ladder recommends administration of a minor opioid in the second step (for moderate pain) and a major opioid in the third step (for severe pain) [16].

During the study, the percentage of patients treated with chemotherapy and bisphosphonates hardly varied, whereas palliative radiotherapy and non-opioids or coadjuvants decreased from baseline to follow-up visits. It has been reported that bisphosphonates and radiation therapy have beneficial effects on reducing metastatic bone pain [17]. However, in the present study, even though the number of patients using these therapies reduced with treatment, these changes were not statistically significant.

Opioids have been successfully used for neuropathic pain since the early 1990s [18], with oxycodone specifically being reported as a beneficial drug in benign neuropathic pain, and as efficacious as morphine in treating oncologic pain [9]. Although the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) still recommends morphine as the first line opioid for cancer patients with moderate to severe pain [19], current European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommendations suggest that the analgesic efficacy and adverse event profile of morphine, oxycodone and hydromorphone are similar in these patients [20]. The results of the present study show that the percentage of patients treated with opioids almost doubled during the study compared with previous treatments, baseline, and follow-up.

Significant improvements in pain, sleep, and functionality found during the first month of treatment in the present study were similar to another Spanish oncologic neuropathic pain study [21]. In that study, 88% of patients were treated with oxycodone, and pharmacologic cancer pain treatment had a greater effect in patients with metastases than in those with no metastases, evidencing its importance in metastatic cancer pain. Analgesic treatment response depended on the specific treatment used, with patients on oxycodone or other opioids showing a greater improvement in pain than patients on treatment other than opioids.

In addition to performance status being dependent on patients’ overall response, our results show that ECOG improvement is closely related to pain. The response to analgesic treatment for palliation of MBP has been found to be significantly related to performance status [22]. Furthermore, the association between pain and performance status seems to be reciprocal, since patients with poor performance status (ECOG ≥ 2), among other variables, are more likely to have SREs, including pain [23]. The change from previous treatment consisted in a decrease in non-opioids or coadjuvants and a 2-fold increase in opioids, due to oxycodone increase (6-fold). Therefore, pain and ECOG improvements observed at months 1 and 3 seem to be the result of the increase in opioid administration. Despite the statistically significant difference in the performance status and pain scores with treatment, the results need to be interpreted with caution considering the validity of measurement methods used. Furthermore, although radiotherapy treatment increased at baseline, it decreased subsequently, and hence would not explain the improvement observed during the follow-up period.

The strengths of this study include the number of patients included in this analysis as well as the observational nature of this study, which allows for the determination of this effect in a real-world setting. However, the unselected nature of the population could mean that there are confounding factors influencing the patients’ perception of their functional status. A major limitation of our study is the lack of information on the physicians' clinical judgments for the choice of treatment and that nearly 80% of patients received baseline oxycodone during the study, indicating that most patients were switched from other opioids to oxycodone which may have introduced bias. Although no differences were observed between oxycodone and the rest of opioids for ECOG, significant differences were observed in pain outcomes. Thus, decrease in pain was significantly greater in patients taking oxycodone, while the proportion of patients with a ≥50% improvement in pain was significantly larger in patients taking oxycodone, and significantly smaller in those taking fentanyl. This suggests that, in patients with MBP, oxycodone, specifically, might improve pain more than other opioids. Furthermore, most of patients received non-opioids or adjuvant analgesics and either chemotherapy or radiotherapy during the study. However, prescription changes of these treatments throughout the observation period did not show statistically significant effects on pain improvement, whilst only the increment of opioid treatment revealed a statistically significant impact on pain relief. Another limitation of this study is that the effects of treatment were only investigated for 3 months; studies investing the long-term influence of pain treatment on clinical outcomes in patients with MBP are warranted.

In conclusion, the current management of MBP in Spain is poor. In fact, pain, sleep, functionality, and ECOG improvements were achieved after changing treatment to a wider range of opioids. Pain and ECOG outcomes are directly related. Opioid treatment seems to have a favorable effect on ECOG and pain evolution in patients with MBP, while the opposite is true of the need for rescue treatment.

References

Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(9):592–6.

Caraceni A, Portenoy RK. An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. IASP task force on cancer pain. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999;82(3):263–74.

Hara S. Opioids for metastatic bone pain. Oncology. 2008;74(Suppl 1):52–4.

Ford JA, Mowatt G, Jones R. Assessing pharmacological interventions for bone metastases: the need for more patient-centered outcomes. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2012;5(3):271–9.

Jiménez-Andrade JM, Mantyh WG, Bloom AP, et al. Bone cancer pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1198:173–81.

Castro MM, Daltro C. Sleep patterns and symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with chronic pain. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2009;67(1):25–8.

Vassiliou V, Kardamakis D. The management of metastatic bone disease with the combination of bisphosphonates and radiotherapy: from theory to clinical practice. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9(3):326–35.

Raphael J, Ahmedzai S, Hester J, et al. Cancer pain: part 1: pathophysiology; oncological, pharmacological, and psychological treatments: a perspective from the British Pain Society endorsed by the UK Association of Palliative Medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners. Pain Med. 2010;11(5):742–64.

Núñez Olarte JM. Oxycodone and the challenge of neuropathic cancer pain: a review. Oncology. 2008;74(Suppl 1):83–90.

Chow E. Update on radiation treatment for cancer pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2007;1(1):11–5.

Fairchild A, Chow E. Role of radiation therapy and radiopharmaceuticals in bone metastases. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2007;1(3):169–73.

Jansen DR, Krijger GC, Kolar ZI, et al. Targeted radiotherapy of bone malignancies. Curr Drug Discov Technol. 2010;7(4):233–46.

Iranikhah M, Wilborn TW, Wensel TM, et al. Denosumab for the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastasis from solid tumor. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(3):274–84.

Zeppetella G. Impact and management of breakthrough pain in cancer. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009;3(1):1–6.

Stacey BR. Management of peripheral neuropathic pain. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(Suppl 3):S4–16.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/. Accessed 16 Oct 2015.

Hoskin PJ. Bisphosphonates and radiation therapy for palliation of metastatic bone disease. Cancer Treat Rev. 2003;29(4):321–7.

Mercadante S, Gebbia V, David F, et al. Tools for identifying cancer pain of predominantly neuropathic origin and opioid responsiveness in cancer patients. J Pain. 2009;10(6):594–600.

Ripamonti CI, Santini D, Maranzano E, et al. Management of cancer pain: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 7):vii139–54.

Hanks GW, Conno F, Cherny N, et al. Morphine and alternative opioids in cancer pain: the EAPC recommendations. Br J Cancer. 2001;84(5):587–93.

García de Paredes ML, del Moral González F, Martínez del Prado P, et al. First evidence of oncologic neuropathic pain prevalence after screening 8615 cancer patients. Results of the on study. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(4):924–30.

Campos S, Presutti R, Zhang L, et al. Elderly patients with painful bone metastases should be offered palliative radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(5):1500–6.

Sun JM, Ahn JS, Lee S, et al. Predictors of skeletal-related events in non-small cell lung cancer patients with bone metastases. Lung Cancer. 2011;71(1):89–93.

Acknowledgements

Sponsorship and article processing charges were funded by Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals S.L. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. We would like to thank the following investigators that participated in the Bone Metastatic Pain Study: Eva María Ciruelos, Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid; Mónica Corral, Hospital Alcañiz, Alcañiz, Teruel; Purificación Martínez del Prado, Hospital Basurto, Bilbao, Vizcaya; Francisco J. Carabantes, Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga; Manuel Cobo, Hospital Carlos Haya, Málaga; Luis Olay, Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias; Diego Soto, Hospital Clínico de Valladolid, Valladolid; Isabel Blancas, Hospital Clínico San Cecilio, Granada; Javier Puente, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid; José Miguel, Hospital Clínico San Cecilio, Granada; Dolores Isla, Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza; Julio José Lambea, Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza; Yolanda López, C. A. de Zamora, Zamora; Irma Muruzabal, Hospital de Cruces, Barakaldo, Vizcaya; José Miguel Martín, Hospital de Getafe, Getafe, Madrid; Salvador Garcerá, Hospital de la Ribera, Alzira, Valencia; Natalia Lupión, Hospital de Mérida, Mérida, Badajoz; Enrique Martínez, Hospital de Navarra, Pamplona, Navarra; Núria Calvo, Hospital de Sant Pau, Barcelona; Sonia Maciá, Hospital General de Elda-Virgen de la Salud, Alicante; Ana Blasco, Hospital General de Valencia, Valencia; José María García, Hospital General de Albacete, Albacete; Enric Carcereny, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona; Esperanza Blanco, Hospital Infanta Cristina, Badajoz; Ana Belén Custodio, Hospital La Paz, Madrid; Juan Bayo, Clínica Los Naranjos, Huelva; Carmen Velilla, Hospital Lozano Blesa, Zaragoza; Almudena García, Hospital Marqués de Valdecilla, Santander; Miguel Méndez, Hospital de Móstoles, Móstoles, Madrid; Román Bastus, Hospital Mutua de Terrassa, Terrassa, Barcelona; Ana María Tortorella, Hospital Naval de Cartagena, Cartagena, Murcia; Yolanda García, Hospital Parc Taulí, Sabadell, Barcelona; José María Puerto, Hospital Perpetuo Socorro, Badajoz; Cristina López, Hospital Povisa, Vigo, Pontevedra; Fátima Navarro, Hospital Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid; Javier Munárriz, Hospital Provincial, Castellón; Ramón de las Peñas, Hospital Provincial, Castellón; Miguel Ruiz, Hospital Punta de Europa, Algeciras, Cádiz; María Fernández, Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid; Laura Murillo, Hospital Reina Sofía, Tudela, Navarra; Isabel Palomo, Hospital Río Hortega, Valladolid; Christian Rolfo, Clínica Rotger, Palma de Mallorca; Antonia Perello, Hospital Son Dureta, Palma de Mallorca; Aránzazu González del Alba, Hospital Son Dureta, Palma de Mallorca; José Manuel Pérez, Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona; Miguel Marín, Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, Murcia; Javier Medina, Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo; Ruth Álvarez, Hospital Virgen de la Salud, Toledo; Francisco de Asís, Hospital Virgen de los Lirios, Alcoy, Alicante; David Vicente, Hospital Virgen Macarena, Sevilla; Manuel Codes, Hospital Virgen Macarena, Sevilla; Guillermo Quintero, Complexo Hospitalario Xeral-Calde, Lugo; Sergio Vázquez, Complejo Hospitalario Xeral-Calde, Lugo; Silvia Antolín, CHUAC, A Coruña; Rafael López, CHUS, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña; Bernardo Queralt, ICO-Girona, Girona. We would like to thank Mayte Martín Fuentes from Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals S.L. for managing the study, and Almudena Pardo and Luis Santamaría, both independent medical writers, for helping in the medical writing of the manuscript. This medical writing assistance was funded by Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals S.L. The authors would also like to thank Simone Boniface of Springer Healthcare Communications, who edited the manuscript for English and styled for submission, and Nishad Parkar, PhD, of Springer Healthcare Communications who edited the manuscript post-submission. This medical writing assistance was funded by Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals S.L.

Disclosures

Susana Traseira Lugilde is a Medical Director at Mundipharma Pharmaceuticals S.L., sponsor of this study. Manuel Dómine Gómez, Nieves Díaz Fernández, Blanca Cantos Sánchez de Ibargüen, Luis Zugazabeitia Olabarría, Joaquina Martínez Lozano, Raúl Poza de Celis, Rafael Trujillo Vílchez, Ignacio Peláez Fernández, Jaume Capdevila Castillón and Emilio Esteban González have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/F317F0603A99857F.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dómine Gómez, M., Díaz Fernández, N., Cantos Sánchez de Ibargüen, B. et al. Association of Performance Status and Pain in Metastatic Bone Pain Management in the Spanish Clinical Setting. Adv Ther 34, 136–147 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0435-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-016-0435-1