Abstract

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), a highly prevalent and impairing psychological condition in adolescents, is characterized by persistent fear of social and performance situations. Existing evidence suggests that racism and discrimination may heighten risk for SAD and present barriers to treatment in Black youth. Yet, intervention research on SAD in Black adolescents is virtually nonexistent. This paper discusses the development of the first culturally responsive, school-based intervention for SAD in Black adolescents, referred to as Interacting and Changing our Narratives (ICON). Following recommendations by Castro et al. (Ann Rev Clin Psychol 6(1):213–239, 2010), a multiple stage process was used to adapt an empirically based, school intervention for SAD to be culturally responsive to the unique lived experiences of Black teenagers. Utilizing a university-community-school partnership, key stakeholders, including content area experts, school personnel, caregivers and students, were invited to participate in this process. Their recommendations guided the modifications, and were clearly reflected in the newly developed intervention. Initial piloting showed high acceptability and feasibility of ICON, and informed further revisions prior to a controlled trial. This adaptation process highlights the significant value of learning directly from the community for which an intervention is being developed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social anxiety disorder (SAD), a debilitating fear and avoidance of performance and social situations, is among the most frequent and impairing psychological conditions in adolescents (Merikangas et al., 2010). The social discomfort and avoidance associated with SAD often restrict school involvement (e.g., school clubs, sports teams) and undermine class performance (e.g., group projects, class participation; Ranta et al., 2013). Despite the well-established connection between SAD to school absence, restricted friendships, academic underperformance, and dropout (Heyne et al., 2011; Kessler, 2003), it goes largely unidentified and untreated (Merikangas et al., 2010).

Specific estimates of SAD in Black adolescents are uncertain, but SAD has the highest prevalence (4.6%) of anxiety disorders for African American adults (PTSD is 3.8%) and the second highest for Caribbean Black Americans (SAD is 4.7% and PTSD is 5.2%; Himle et al., 2009). Further, SAD in Black individuals has a more insidious and chronic course than in White individuals (Sibrava et al., 2013), with most cases developing before age 20 (Himle et al., 2009). Racial discrimination, which is frequent and pervasive (Seaton et al., 2008), has been shown to be uniquely related to SAD (Levine et al., 2014). Black youth with excessive concerns about others’ evaluations, the core feature of SAD, may be vulnerable to internalizing racism, or accepting negative messages about oneself, and in turn, experience further harmful consequences (e.g., lower achievement, weakened Black identity; Brown & Segrist, 2016; Chapman et al., 2013a). In fact, recent research supports that internalized racism may explain the connection between racist experiences and SAD (Graham et al., 2016; Kline et al., 2021). Moreover, SAD weakens the quality of peer and teacher relationships, which have been documented to be central to school engagement in Black students (Murray & Zvoch, 2010; Williams & Bryan, 2013). As most school personnel are from other racial/ethnic groups, interracial anxiety, or discomfort interacting with those of other ethnic/racial backgrounds due to expected negative outcomes, may limit Black students’ educational opportunities (Hunter & Schmidt, 2010; Plant & Devine, 2003). Finally, nonverbal behaviors characteristic of SAD (e.g., gaze aversion and frowning) may be misinterpreted as unfriendliness or opposition in Black youth, potentially increasing their hesitance to connect with school personnel (Bottiani et al., 2017; Kunesh & Noltemeyer, 2019). Possibly due to similar biases, research on internalizing problems in Black students has been neglected relative to externalizing behaviors (Nebbitt & Lambert, 2009). Despite the clear import of SAD in this population, intervention research is virtually nonexistent.

Schools are uniquely positioned to address treatment challenges specific to SAD. Black youth have less access to specialty mental health care (Alegría et al., 2012), and are more likely to accept mental health services at school than in clinic settings (Lindsey et al., 2010). School personnel can be educated to identify SAD, thereby facilitating increased detection and treatment access. In addition, as the majority of feared situations occur at school (e.g., talking to peers, eating in the cafeteria, speaking up in class), this setting provides opportunities for real-life exposures (e.g., answering class questions, joining peers in the library) in an authentic environment (Masia Warner et al., 2005, 2007). Teachers and peers can be enlisted to assist with practice, and school counselors can provide additional coaching and encouragement (Ryan & Masia Warner, 2012). Likely due to these advantages, a meta-analysis of cognitive behavioral treatments (CBT) for pediatric SAD (Scaini et al., 2016) reported significantly higher treatment effects for school interventions (g = 1.55) than those in traditional clinical settings (g = 0.67).

The most studied CBT, school intervention for SAD is Skills for Academic and Social Success (SASS; Masia Warner et al., 2005, 2007, 2016, 2018). Delivered in a group format, SASS emphasizes cognitive reappraisal, social skills training, and exposure in school situations. SASS consists of: (1) 12 group school sessions (40 min), (2) two individual meetings (15 min), (3) four weekend social events (90 min), (4) two caregiver meetings (45 min), (5) two booster sessions (40 min), and (6) meetings with teachers as needed. The 12 school sessions include: one psychoeducational session, one session on realistic thinking, four social skills training sessions (i.e., initiating conversations, maintaining conversations and establishing friendships, listening and remembering, and assertiveness), five exposure sessions, and one session on relapse prevention. Exposures are regularly integrated into the school environment and involve school personnel. The two individual meetings identify goals and problem-solve obstacles. The four social events provide real-world exposures and opportunities for skills generalization. Group members practice program skills with school peers (called peer assistants), who have previously participated in SASS. Caregiver meetings focus on psychoeducation about SAD and ways to manage their children’s anxiety. Lastly, two monthly booster sessions discuss maintaining progress (Masia Warner et al., 2018).

A meta-analysis of SASS (Mychailyszyn, 2017), including two pilot studies and three controlled trials, reported an effect size (Hedge’s g) of 1.06 (95% CI [0.58, 1.54], p < 0.001) for self-reported social anxiety symptoms. A subsequent trial, in 138 high school students, evaluated whether SASS could be effectively implemented by school counselors (Masia Warner et al., 2016). Students were randomized to: (a) SASS delivered by trained school counselors (C-SASS), (b) SASS delivered by clinical psychologists (P-SASS), or (c) general school counseling (GC). Both at posttreatment and 5-month follow-up, participants in C-SASS and P-SASS had lower SAD severity than those in GC. Also, at both time-points, treatment response was significantly greater in C-SASS (65 and 85%) and P-SASS (66 and 72%) than in GC (18.6 and 25.6%), and diagnostic remission was higher for C-SASS (22 and 39%) and P-SASS (28 and 28%) than GC (7 and 12%). No differences between C-SASS and P-SASS were found (Masia Warner et al., 2016).

Given the evidence for SASS’ impact and the importance of addressing SAD in Black youth, the current project sought to broaden its cultural responsivity. Cultural responsiveness, as defined by the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP, 2021), is “acknowledging and incorporating cultural considerations in the design, implementation, and evaluation of practices and services; infusing understanding and value for individual and groups’ cultural differences and preferences into practice” (p. 3). This process is particularly crucial when cultural risk or resilience factors are present and engaging the group in treatment has proven difficult (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Hwang, 2016; Robinson et al., 2015). As unique risk factors (i.e., discrimination, internalized racism) and treatment engagement challenges exist for Black adolescents with SAD, the expectation is that improving the cultural responsiveness of SASS will ultimately increase treatment enrollment and effectiveness for racial minorities (Castro & Yasui, 2017; Clarke et al., 2022; Metzger et al., 2021).

Project Objectives

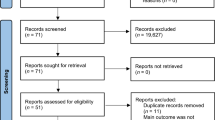

The paper aims to describe the extensive university-community collaboration used to adapt SASS to be culturally responsive to the needs of Black high school students. Given the documented efficacy of CBT (Mychailyszyn, 2017; Scaini et al., 2016), we aimed to retain SASS’ core CBT ingredients (i.e., cognitive reappraisal, exposure, social skills training), while ensuring an appropriate cultural context for students and the school community (Castro et al., 2010). In line with the Barrera and Castro (2006) cultural adaptation model, the adaptation process began with preliminary information gathering followed by two studies. The purpose of Study One was to obtain a better understanding of the cultural, school, and community context from the perspectives of students and caregivers with the goal of informing the preliminary modification of SASS. Study Two consisted of piloting the culturally adapted intervention to evaluate its feasibility and acceptability and identify further needed revisions.

Preliminary Information Gathering

Prior to conducting qualitative assessments with students and caregivers in Study One, it was important to identify potentially relevant topics. We started by reviewing the literature on cultural factors pertaining to anxiety, racism and discrimination, racial identity, and help-seeking behaviors in Black youth. In addition, we assembled a racially and ethnically diverse team of community members and educational stakeholders with extensive experience working in communities of color, our Community Development Team (CDT), and enlisted experts in addressing mental health in the Black community.

The CDT included the Director of the New Jersey Professional Development Schools Network (White female, 23 years in position), as well as the Head of Guidance (Black male, five years in position), Parent Coordinator (Black male, five years in position), and two school counselors (a Black female with 3 years in position and a Latina female with 11 years in position). All school personnel were employed in a public high school in a community of color. The expert consultants were Drs. Michael Lindsey (Black male), Jamaal Matthews (Black male), and Kira Banks (Black female). We briefly summarize the initial considerations, both in Table 1 and below, that were identified.

Treatment Engagement

The CDT expressed doubts about Black families’ willingness to participate in school mental health services. This feedback was consistent with studies of Black youth reporting concerns about stigma or shame being significant treatment barriers. They may be encouraged to use willpower or “tough it out” as opposed to asking for help. In addition, Black culture may broadly hold social norms that children’s problems should remain within the family (Lindsey et al., 2014; Murry et al., 2011). Finally, adolescents and caregivers may have negative expectations about services, like doubts about effectiveness, concerns about therapists’ cultural sensitivity, and cultural mistrust due to discrimination and racism (Hunter & Schmidt, 2010; Lindsey et al., 2014). To address these factors, we consulted Dr. Lindsey, about his engagement intervention, The Making Connections Treatment Engagement Intervention (MCI; Lindsey et al., 2009), for Black adolescents with depression. MCI is conducted in individual, hour long sessions with students and their caregivers. The CDT thought that having school counselors conduct multiple individual sessions and that having working caregivers attend daytime school meetings were impractical. Thus, we planned to modify MCI to a group format with students and meet separately with parents in a virtual format.

Addressing Racial Discrimination

While exaggerated concerns about others’ evaluation are central to all individuals with SAD (e.g., no one is going to like me), Black students also experience self-focused, negative thoughts concerning racist incidents in which they are not misperceiving negative judgment (Chapman et al., 2013b; Graham et al., 2016). Those with SAD are more likely to accept these negative racial messages as true, placing them at increased risk for concomitant academic impairment. Thus, the literature reinforced that the intervention had to address negative perceptions stemming from racism (Graham et al., 2012) and prevent internalization of negative messages (Kline et al., 2021). CBT addresses anxious thoughts by treating them as overly catastrophic or unrealistic predictions; however, this approach might invalidate experiences of racism. Thus, our goal was to expand cognitive strategies to circumvent the internalization of discrimination experiences by rightfully attributing them externally to systemic prejudices (Graham et al., 2012). We enlisted the expertise of Dr. Banks, known for her work extracting internalized racism with Black women (Banks & Stephens, 2018), to advise the development of this critical component.

Racial Empowerment

As chronic experiences of discrimination and racism are linked to lower self-esteem and decreased identification with racial background (Blackmon & Thomas, 2013; Brown & Segrist, 2016), Dr. Matthews suggested that the intervention include bolstering students’ racial identity, a chief aspect of resiliency against discrimination (Seaton et al., 2010). Based on his own THREADS mentoring program for marginalized male youth in urban schools (Matthews, 2002), Dr. Matthews recommended teaching adolescents about their heritage, identifying areas of pride and resilience, discussing counter-narratives to pervasive stereotypes, and preparing youth to cope with instances of discrimination (Neblett Jr et al., 2012).

SASS Strategies

As assertiveness in Black adolescents may be stereotyped as aggressive, the CDT and Dr. Banks suggested revising assertiveness instruction to include potential negative reactions. Moreover, in implementing exposure (gradually entering anxiety-provoking situations), CDT members suggested practicing interracial interactions with school personnel and peers.

Study One: Student and Caregiver Participants

To ensure that modifications were aligned with the lived experiences of the target population, focus groups and interviews were conducted with Black high school students and caregivers. A full description is beyond the scope of this paper, but key findings that informed intervention revisions are summarized.

Participants

Students and caregivers from an urban high school in the northeastern USA were recruited through teacher nominations and parent-teacher organization meetings. Fifteen students (56.25% female) with a mean age of 16 years (SD = 1.2, range = 14–18) participated in focus groups, with seven of the 15 also completing individual interviews. Eleven of the 15 students were Black (73.33%), two were Black and Latinx (13.33%), and two Biracial (13.33%). In addition, nine caregivers participated (100% female; 100% Black), including seven mothers, one grandmother, and one sister. Their mean age was 46.78 years (SD = 6.76, range = 37–54). Six caregivers participated in focus groups, with four of them also completing interviews. In addition, three new mothers completed individual interviews only for a total of seven interviews.

Qualitative Methods

Focus groups and interview guides originated from the work of Dr. Lindsey with Black adolescents with depression (Lindsey et al., 2012, 2014), but adapted to emphasize SAD. They included questions about cultural factors related to SAD, potential barriers to participating in school services, and recommendations for school-based group intervention. Four student and two caregiver focus groups were conducted at school. Student individual interviews were also conducted at school, but caregiver interviews took place virtually. Focus groups and interviews were led by psychology graduate students of color and audio-recorded for transcription and coding. A systematic coding process was supervised by qualitative expert Dr. Helen-Maria Lekas. Quotes are paraphrased to protect confidentiality.

Findings: Themes that Informed Intervention Adaptation

Treatment Engagement

See Table 1 for a summary of themes that informed the adapted intervention. Consistent with Lindsey et al. (2014), students and caregivers raised concerns about stigma. Additionally, they mentioned concerns about appearing weak to others and a preference to handle problems on their own. One caregiver stated that “if her child went to see a counselor, he would have to worry about being labeled as crazy.” According to a student, “talking about your problems is not something a lot of people want to do. Most people move on with life, just deal with it themselves. It’s not really healthy, but it’s something that people do.”

Nevertheless, positive perceptions of school mental health services were expressed. Caregivers indicated that they supported their child seeking mental health services at school; “It is a release and if at the moment [student] is feeling some type of way, and that’s where he needs to go to let it out. Then, yes, I feel 100% I’m with it.” A student shared a similar sentiment about school services stating, “having someone to go talk to could really help, cause they're letting all of that out, like all that stress and like sadness.”

When asked about racial preference for school counselors, about half of students and caregivers reported a preference for a counselor with the same ethnic background or a deep understanding of the experiences of Black youth. They believed this would create a more familiar atmosphere for Black students to receive mental health support. One caregiver expressed, “they have to have at least grown up around or know what it is to be a Black child, to come up in a Black household, to know what goes on in the Black household to help these students. If you have someone that’s sitting there with a degree that’s book smart but they have no acknowledgment of what happens on the street, how can they help that child?”.

Furthermore, caregivers and students suggested making the intervention a club that is held in a casual school setting. One student expressed that treatments in the school setting with other students would be more comfortable than meeting with a stranger in a clinic. Another student suggested that, “hearing other people’s point of view and relating to the people in the group” would reduce reluctance to participate. Consistently, caregivers said, “don’t have it in a literal office setting so a label won’t be put on them or to hold it on a playground or somewhere to break the ice where it doesn’t feel like a real counseling session.” Another caregiver recommended removing clinical terminology from the intervention, indicating “you got to get to their level. Don’t call it counseling or psychiatry, just take that whole counseling word out and call it a rap or talking session. You may get more people to feel comfortable about coming.”

Addressing Racial Discrimination

Students and caregivers raised racism as the most important cultural factor. As captured by one student, “I think racism makes it harder for them to make friends, like what if they won’t like me because I’m Black. It makes you get closed off from everybody and everything.” A caregiver described, “I could see where somebody that's Black or Brown would have anxiety going into a lot of situations because you don't know if someone is judging you based off of you, or just the way that you look.” Most suggested incorporating strategies for coping with microaggressions and discrimination. One student said, “you could tell them that someone can call you a certain name, it doesn't mean that you're that name, someone just wants to be mean to you, you don't have to believe it.” Similarly, caregivers proposed telling students that “it has nothing to do with them so they don’t internalize it and to give them tools so that they can navigate through that situation as best as they can.”

Racial Empowerment

Caregivers and students responded positively to promoting cultural pride. As expressed by one caregiver, “that’s really good. It gives them a positive impact of who they are and esteem.” Similarly, one student responded, “it lets them know there’s people out there into the positivity of being Black and not just the negative.” One recommendation was to include modern Black role models to diversify adolescents’ knowledge of successful Black leaders. One student recommended, “kind of talk about the culture, and how successful Black people are and how they dealt with battles because of their skin color.”

SASS Strategies: Assertiveness Training

Students and caregivers highlighted the importance of students learning skills to advocate for themselves. One student thought it would be essential for students to learn “to stand up for themselves better, without being aggressive or being upset or crying.” A caregiver expressed a similar sentiment stating that Black students need to know how to be assertive “in an order where they are respectfully doing it, because you don’t want anybody to be assertive and be angry. You want them to be able to express themselves properly.” Additional recommendations involved teaching skills to communicate with adults, using a friendly and approachable demeanor, and making sure to practice in groups.

Implications of Study One: Initial School ICON Meetings

Data were used to adapt SASS and develop Interacting and Changing Our Narratives (ICON). Based on student and caregiver suggestions to ensure a casual, less stigmatizing format, ICON was referred to as a club program and club t-shirts, with a newly designed ICON logo, were made. Like SASS, ICON included 12 school meetings lasting approximately one class period. However, the school sessions were substantially changed from the original version. ICON consisted of: one new session to address cultural barriers to treatment engagement using MCI strategies (Lindsey et al., 2009), one revised psychoeducational session incorporating ways in which racism and discrimination exacerbate SAD, one revised cognitive session with expanded strategies to target internalized racism (Banks et al., 2021), one new racial empowerment session, three (reduced from four) revised social skills training sessions, four (reduced from five) exposure sessions, and one final wrap-up session. In addition, we included one 45-min virtual meeting with caregivers to provide psychoeducation about SAD and to address potential barriers to treatment engagement. See Table 2 for a summary of the main components of ICON sessions.

Study Two: Piloting of ICON

Study Two involved delivering ICON in an open pilot to inform additional changes and assess its acceptability and feasibility. A full description of the pilot is beyond the scope of this paper. We focus solely on the quantitative and qualitative data that informed ICON revisions.

Open Pilot Methods

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from a public high school in an urban community of color. Following brief presentations about SAD at faculty meetings, school personnel were asked to nominate potentially appropriate Black students to school counselors. School counselors then reviewed the nominations and provided the research team with a final list of 29 referred students. Twelve caregivers and students provided written consent and were evaluated for study eligibility. To be included, students had to self-identify as Black and receive a full (meet all diagnostic criteria) or subthreshold (missing one diagnostic criteria) diagnosis of SAD. Students with subthreshold SAD were considered important to include, as symptoms are associated with limitations that can worsen over time (Fehm et al., 2008; Knappe et al., 2009).

Students were interviewed at school by a doctoral level psychologist on the research team using the SAD section of the Anxiety and Related Disorders Interview Schedule (ADIS-IV-C; Silverman & Albano, 1996). Clinical severity ratings (CSR) from 0 to 8 are assigned, with ratings of 4 or above indicating a full diagnosis and 3 indicating subthreshold SAD symptoms. Of the 12 students interviewed, 11 were eligible to participate. One student was excluded due to a suspected diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder.

Participants

The 11 students (n = 10 Black and 1 Biracial) included six males and five females (Mage = 15.73, SD = 1.27). The majority (n = 6) were in the tenth grade. Eight students met full SAD criteria, and three had subthreshold symptoms. The students had a mean ADIS CSR rating of 4.45 (SD = 1.29), suggesting moderate social anxiety severity.

Student Assessments

To assess social anxiety symptoms, students completed the 7 item Social Anxiety Subscale of the Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED; Birmaher et al., 1997). Students completed seven social anxiety items on a three-point rating scale, ranging from 0 (Not True or Hardly Ever True) to 2 (Very True or Often True), with a score of eight or above suggesting SAD. Students had a mean SCARED SAD subscale score of 7.82 (SD = 3.22), with four students scoring above the clinical cut off.

The University Rhode Island Change Assessment Scale (URICA; McConnaughy, 1981) was used to assess students’ readiness for change or openness to intervention. It consists of 32 self-report items, rated on a five-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), calculated to provide one of four stages: Precontemplation, Contemplation, Action, and Maintenance. Students were either in the Precontemplation (27.3%) or Contemplation (72.7%) stages, indicating a lack of problem recognition or a hesitance to change, respectively.

The Barriers to Adolescent Seeking Help Scale (BASH; Kuhl et al., 1997) was used to assess which treatment barriers to address in the first session of ICON. Thirty-seven items (e.g., My friends would think I was crazy if I joined a skills program” and “If I had a problem, I would solve it by myself”) were rated on a 3-point Likert scale. The most problematic barriers were concerns about confidentiality, wanting to handle problems independently, and wanting to keep problems within the family.

School Counselor Characteristics

Two school counselors of color volunteered to co-lead the ICON groups with clinical psychologists from the research team (the first author and a postdoctoral fellow). School counselors completed an assessment of CBT knowledge, attitudes toward evidence-based practice, and multicultural self-efficacy. Table 3 presents school counselors’ demographic and assessment information. School counselors demonstrated limited knowledge of CBT techniques for youth anxiety, but were favorable toward implementing evidence-based practices. In addition, they perceived themselves to have strong multicultural self-efficacy.

ICON Pilot Delivery

Two ICON groups (n = 5; 2 females and 3 males in Group 1 and n = 6; 3 females and 3 males in Group 2) were conducted. The mixed gender groups were considered advantageous for skills practice and exposures because most adolescents with SAD report heightened anxiety in heterosocial interactions. One male student discontinued after the second session, leaving four students in Group 1. Among the 10 completers, students attended an average of 10.3 (85.8%) of the 12 groups. Nine of the 11 (81.8%) caregivers participated in the virtual meeting. The four group co-leaders met weekly to prepare for the upcoming group (e.g., divide session parts, review treatment strategies) and discuss the quality of implementation and flow of the previous session, including recommended revisions.

Findings: ICON Satisfaction, Feasibility, and Acceptability

Student and School Counselor ICON Satisfaction Ratings

Following ICON, students completed a satisfaction questionnaire, developed for the pilot study, to rate ICON’s value in reducing nervousness, increasing social comfort and school engagement, and whether they would recommend ICON to a friend. Students also rated how important and enjoyable they found each ICON session. As shown in Table 4, overall ratings were high for ICON’s helpfulness and for the importance and enjoyment of ICON sessions.

Similarly, school counselors were asked to rate ICON’s effectiveness in addressing SAD and its cultural responsiveness to Black students. In addition, they were asked to indicate how confident they felt co-leading ICON and whether they would recommend it to other school counselors. They also rated how important and enjoyable they found each ICON session. As seen in Table 4, both school counselors indicated the highest possible satisfaction across all ratings. Overall, these data suggest that ICON was highly regarded by both students and counselors.

Student Written Feedback

Generally, the students provided positive written feedback about ICON. The majority reported feeling sad that the ICON club had ended, and thus, school counselors were asked to hold a booster meeting. One student wrote, “It was a really good experience and helped me improve so much and changed how I handled certain situations and thoughts.” Another student noted, “It helped me and the way I speak to others and what I say.” Further, students made favorable comments about ICON’s environment. One student stated, “I like how they make working with our problems fun.” Students also provided constructive feedback that was used to inform further ICON revisions, as summarized in Table 2.

School Counselor Verbal and Written Feedback

School counselors provided verbal feedback during weekly consultation meetings, as well as written feedback after ICON completion. One counselor wrote, “I had a great and amazing experience as I learned valuable information. I would love the opportunity to do it again with new students, as it is awesome and life-changing.” The other counselor noted, “In schools, it is not easy to fully commit to a program with the different tasks that pop up day to day. It was very refreshing to see that after 12 weeks of sticking to a structured program, I was able to witness tremendous growth in them.” Counselors also provided constructive feedback that was used to inform further ICON revisions, as summarized in Table 2.

Study Two Implications

ICON was a positive experience for students and counselors, as evidenced by high satisfaction ratings, robust attendance, and minimal drop-out. In addition, 80% of participants expressed enthusiasm to return as program peer assistants for future ICON implementation, and both school counselors asked to continue as group leaders. The feedback from the open pilot provided meaningful information that has led to further revisions to enhance the cultural responsiveness of ICON. As seen in Table 2, to continue prioritizing students’ treatment engagement, peer assistants will be invited to discuss their initial reactions to joining ICON and the way it improved their lives. In addition, to demonstrate that ICON is specifically designed for Black students, racial empowerment strategies will be moved earlier and applied to counter negative race-related thoughts. An additional exposure session will be included with more emphasis on interacting with teachers and becoming connected at school. Lastly, at the final ICON session, students will present their favorite Black role models to reinforce racial pride.

Discussion

This paper describes an extensive collaborative process used to amplify the voices of the Black community in building the first culturally responsive intervention targeting SAD in adolescents. Given the challenges associated with racism and discrimination and their link to SAD, it was critical that the adaptation incorporate components that shed light on the lived and often undermined experiences of Black youth. Core CBT strategies were maintained for effectiveness, but rich feedback from students, caregivers, and community stakeholders was directly translated into tangible changes reflecting the target population’s cultural strengths and challenges. This effort adds to a small but growing body of literature suggesting value in modifying evidence-based treatments to assist Black youth in overcoming stressors pertinent to their experiences (Clarke et al., 2022; Metzger et al., 2021).

The development process is intensive, and some question whether cultural adaptation is justified when the original version may be effective or when challenges in methodological rigor make it difficult to compare effectiveness to standard evidence-based interventions (Rathod et al., 2018). It is certainly plausible that there would not be statistically significant differences in quantitative outcomes if SASS and ICON were directly compared. Yet, our preliminary results suggest that ICON was positively received and resonated with Black students, who have left us with the lasting impression that they felt deeply seen and heard by this intervention. These findings are particularly encouraging given the common barriers to mental health services in communities of color, including concerns about stigma, shame, perceived weakness, and mistrust in treatment due to racism (Hunter & Schmidt, 2010; Misra et al., 2021). Culturally responsive interventions delivered in an accessible setting like school have the potential for engaging and empowering historically marginalized youth who have been reluctant to seek treatment and face logistical barriers to receiving traditional mental health services. Like other similar efforts for depression and trauma (Clarke et al., 2022; Metzger et al., 2021), this approach may be key to reducing the well-documented racial disparities in mental health service use.

Now that ICON has undergone extensive revision with attention given to the needs of Black students, the next step will be to evaluate its potential efficacy through a randomized controlled trial comparing ICON to standard school counseling. The pilot work was limited to a small sample in one school community composed of a majority of low-income families from racial and ethnic minorities. Recognizing the likely influence of socioeconomic and racial diversity on school climate, discrimination experiences, and social discomfort with peers and teachers, we will expand school districts to establish broader acceptability. In addition to evaluating social anxiety symptoms and school functioning, it will be essential to assess treatment and school engagement and retention. We will also assess school climate and determine the feasibility of including peer assistants and teacher involvement in classroom exposures.

We are optimistic that ICON will help engage a population that has been understandably reluctant to seek services. Given the paucity of treatment research in racial minorities, we hope that sharing this process will encourage additional efforts in this highly under-researched area that will contribute to addressing mental health disparities and promoting mental health equity.

References

Aarons, G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: The evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6(2), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:mhsr.0000024351.12294.65

Alegría, M., Lin, J. Y., Green, J. G., Sampson, N. A., Gruber, M. J., & Kessler, R. C. (2012). Role of referrals in mental health service disparities for racial and ethnic minority youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.005

Banks, K. H., Goswami, S., Goodwin, D., Petty, J., Bell, V., & Musa, I. (2021). Interrupting internalized racial oppression: A community-based ACT intervention. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 20, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.02.006

Banks, K. H., & Stephens, J. (2018). Reframing internalized racial oppression and charting a way forward. Social Issues and Policy Review, 12(1), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/sipr.12041

Barrera, M., & Castro, F. G. (2006). A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13(4), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00043.x

Beidas, R. S., Edmunds, J. M., Marcus, S. C., & Kendall, P. C. (2012). Training and consultation to promote implementation of an empirically supported treatment: A randomized trial. Psychiatric Services, 63(7), 660–665. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100401

Birmaher, B., Khetarpal, S., Brent, D., Cully, M., Balach, L., Kaufman, J., & Neer, S. M. (1997). The screen for child anxiety related emotional disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(4), 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018

Blackmon, S. M., & Thomas, A. J. (2013). Linking contextual affordances. Linking Contextual Affordances: Examining Racial-Ethnic Socialization and Parental Career Support among African American College Students, 41(4), 301–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845313495588

Bottiani, J. H., Bradshaw, C. P., & Mendelson, T. (2017). A multilevel examination of racial disparities in high school discipline: Black and white adolescents’ perceived equity, school belonging, and adjustment problems. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(4), 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000155

Brown, D. L., & Segrist, D. (2016). African American career aspirations: Examining the relative influence of internalized racism. Journal of Career Development, 43(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845315586256

Castro, F. G., Barrera, M., & Holleran Steiker, L. K. (2010). Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6(1), 213–239. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032

Castro, F. G., & Yasui, M. (2017). Advances in EBI development for diverse populations: Towards a science of intervention adaptation. Prevention Science, 18(6), 623–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0809-x

Chapman, L. K., DeLapp, C. T. R., & Williams, M. T. (2013a). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of social anxiety among ethnic minority patients, part 1: Understanding differences. Directions in Psychiatry, 33(3), 151–162.

Chapman, L. K., DeLapp, C. T. R., & Williams, M. T. (2013b). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of social anxiety among ethnic minority patients, part 2: Bridging the gap in treatment. Directions in Psychiatry, 33(3), 151–162.

Clarke, A. T., Soto, G. E., Cook, J., Iloanusi, C., Akwarandu, A., & Still Parris, V. (2022). Adaptation of the coping with stress course for black adolescents in low-income communities: Examples of surface structure and deep structure cultural adaptations. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 29(4), 738–749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2021.04.005

Fehm, L., Beesdo, K., Jacobi, F., & Fiedler, A. (2008). Social anxiety disorder above and below the diagnostic threshold: Prevalence, comorbidity and impairment in the general population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(4), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-007-0299-4

Graham, J. R., West, L. M., Martinez, J., & Roemer, L. (2016). The mediating role of internalized racism in the relationship between racist experiences and anxiety symptoms in a black American sample. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 369–376. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000073

Graham, J. R., West, L. M., & Roemer, L. (2012). The experience of racism and anxiety symptoms in an African-American sample: Moderating effects of Trait mindfulness. Mindfulness, 4(4), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0133-2

Heyne, D., Sauter, F. M., Van Widenfelt, B. M., Vermeiren, R., & Westenberg, P. M. (2011). School refusal and anxiety in adolescence: Non-randomized trial of a developmentally sensitive cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(7), 870–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.006

Himle, J. A., Baser, R. E., Taylor, R. J., Campbell, R. D., & Jackson, J. S. (2009). Anxiety disorders among African Americans, Blacks of Caribbean descent, and non-Hispanic whites in the United States. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(5), 578–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.002

Holcomb-McCoy, C., Harris, P., Hines, E. M., & Johnston, G. (2008). School counselors’ multicultural self-efficacy: A preliminary investigation. Professional School Counseling, 11(3), 166–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0801100303

Hunter, L. R., & Schmidt, N. B. (2010). Anxiety psychopathology in African American adults: Literature review and development of an empirically informed sociocultural model. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018133

Hwang, W. C. (2016). Culturally adapting evidence-based practices for ethnic minority and immigrant families. Evidence-Based Psychological Practice with Ethnic Minorities: Culturally Informed Research and Clinical Strategies. https://doi.org/10.1037/14940-014

Kessler, R. C. (2003). The impairments caused by social phobia in the general population: Implications for intervention. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108, 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.2.x

Kline, E. A., Masia Warner, C., Grapin, S. L., Reyes-Portillo, J. A., Bixter, M. T., Cunningham, D. J., Mahmud, F., Singh, T., & Weeks, C. (2021). The relationship between social anxiety and internalized racism in black young adults. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 35(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1891/jcpsy-d-20-00030

Knappe, S., Beesdo, K., Fehm, L., Lieb, R., & Wittchen, H.-U. (2009). Associations of familial risk factors with social fears and social phobia: Evidence for the continuum hypothesis in social anxiety disorder? Journal of Neural Transmission, 116(6), 639–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-008-0118-4

Kuhl, J., Jarkon-Horlick, L., & Morrissey, R. F. (1997). Measuring barriers to help-seeking behavior in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26(6), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022367807715

Kunesh, C. E., & Noltemeyer, A. (2019). Understanding disciplinary disproportionality: Stereotypes shape pre-service teachers’ beliefs about black boys’ behavior. Urban Education, 54(4), 471–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085915623337

Levine, D. S., Himle, J. A., Abelson, J. M., Matusko, N., Dhawan, N., & Taylor, R. J. (2014). Discrimination and social anxiety disorder among African-Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic whites. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(3), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0000000000000099

Lindsey, M. A., Bowery, E., Smith, K., & Stiegler, K. (2009). Treatment manual: The making connections intervention (MCI) manual: Improving treatment acceptability among adolescents in mental health services. University of Maryland.

Lindsey, M. A., Brandt, N. E., Becker, K. D., Lee, B. R., Barth, R. P., Daleiden, E. L., & Chorpita, B. F. (2014). Identifying the common elements of treatment engagement interventions in children’s mental health services. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(3), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0163-x

Lindsey, M. A., Chambers, K., Pohle, C., Beall, P., & Lucksted, A. (2012). Understanding the behavioral determinants of Mental Health Service use by urban, under-resourced black youth: Adolescent and caregiver perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9668-z

Lindsey, M. A., Joe, S., & Nebbitt, V. (2010). Family matters: The role of mental health stigma and social support on depressive symptoms and subsequent help seeking among African American boys. Journal of Black Psychology, 36(4), 458–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798409355796

Masia Warner, C., Colognori, D., Brice, C., Herzig, K., Mufson, L., Lynch, C., Reiss, P. T., Petkova, E., Fox, J., Moceri, D. C., Ryan, J., & Klein, R. G. (2016). Can school counselors deliver cognitive-behavioral treatment for social anxiety effectively? A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(11), 1229–1238. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12550

Masia Warner, C., Colognori, D., & Lynch, C. (2018). Helping students overcome social anxiety: Skills for academic and social success (SASS). Guilford Publications.

Masia Warner, C., Fisher, P. H., Shrout, P. E., Rathor, S., & Klein, R. G. (2007). Treating adolescents with social anxiety disorder in school: An attention control trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(7), 676–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01737.x

Masia Warner, C., Klein, R. G., Dent, H. C., Fisher, P. H., Alvir, J., Marie Albano, A., & Guardino, M. (2005). School-based intervention for adolescents with social anxiety disorder: Results of a controlled study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(6), 707–722. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-7649-z

Matthews, J. S. (2002). Threads. Threads Mentorship Program. https://threadsmentorship.org/

McConnaughy, E. (1981). Development of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment (URICA) Scale: A device for the measurement of stages of change. https://doi.org/10.23860/thesis-mcconnaughy-eileen-1981

Merikangas, K. R., He, J., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., Benjet, C., Georgiades, K., & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017

Metzger, I. W., Anderson, R. E., Are, F., & Ritchwood, T. (2021). Healing interpersonal and racial trauma: Integrating racial socialization into trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for African American youth. Child Maltreatment, 26(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520921457

Misra, S., Jackson, V. W., Chong, J., Choe, K., Tay, C., Wong, J., & Yang, L. H. (2021). Systematic review of cultural aspects of stigma and mental illness among racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States: Implications for interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 68(3–4), 486–512. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12516

Murray, C., & Zvoch, K. (2010). Teacher-student relationships among behaviorally at-risk african american youth from low-income backgrounds: Student perceptions, teacher perceptions, and socioemotional adjustment correlates. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 19(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426609353607

Murry, V. M., Heflinger, C. A., Suiter, S. V., & Brody, G. H. (2011). Examining perceptions about mental health care and help-seeking among rural African American families of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(9), 1118–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9627-1

Mychailyszyn, M. P. (2017). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the skills for social and academic success (SASS) program. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 10(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730x.2017.1285709

National Association of School Psychologists (NASP). (2021). Social justice definitions. National Association of School Psychologists. https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/diversity-and-social-justice/social-justice/social-justice-definitions

Nebbitt, V. E., & Lambert, S. F. (2009). Correlates of anxiety sensitivity among African American adolescents living in urban public housing. Journal of Community Psychology, 37(2), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20292

Neblett, E. W., Rivas-Drake, D., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2012). The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives, 6(3), 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x

Plant, E. A., & Devine, P. G. (2003). The antecedents and implications of interracial anxiety. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(6), 790–801. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203029006011

Ranta, K., Kaltiala-Heino, R., Fröjd, S., & Marttunen, M. (2013). Peer victimization and social phobia: A follow-up study among adolescents. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(4), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0583-9

Rathod, S., Gega, L., Degnan, A., Pikard, J., Khan, T., Husain, N., Munshi, T., & Naeem, F. (2018). The current status of culturally adapted mental health interventions: A practice-focused review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 165–178. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.s138430

Robinson, W. L., Droege, J. R., Case, M. H., & Jason, L. A. (2015). Reducing stress and preventing anxiety in African American adolescents: A culturally-grounded approach. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice. https://doi.org/10.7728/0602201503

Ryan, J. L., & Masia Warner, C. (2012). Treating adolescents with social anxiety disorder in schools. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 21(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2011.08.011

Scaini, S., Belotti, R., Ogliari, A., & Battaglia, M. (2016). A comprehensive meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral interventions for social anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 42, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.05.008

Scottham, K. M., Sellers, R. M., & Nguyên, H. X. (2008). A measure of racial identity in African American adolescents: The development of the multidimensional inventory of Black identity-teen. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority, 14(4), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.297

Seaton, E. K., Caldwell, C. H., Sellers, R. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2008). The prevalence of perceived discrimination among African American and Caribbean Black Youth. Developmental Psychology, 44(5), 1288–1297. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012747

Seaton, E. K., Caldwell, C. H., Sellers, R. M., & Jackson, J. S. (2010). An intersectional approach for understanding perceived discrimination and psychological well-being among African American and Caribbean Black Youth. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1372–1379. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019869

Sibrava, N. J., Beard, C., Bjornsson, A. S., Moitra, E., Weisberg, R. B., & Keller, M. B. (2013). Two-year course of generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder in a longitudinal sample of African American adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 1052–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034382

Silverman, W., & Albano, A. (1996). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

Williams, J. M., & Bryan, J. (2013). Overcoming adversity: High-achieving African American Youth’s perspectives on Educational Resilience. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00097

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This research is supported by a grant from the Institute of Education Sciences (R305A200013) awarded to Dr. Carrie Masia Warner.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Masia Warner, C., Escobar, M., Thomas, H. et al. A University-Community Partnership to Develop a Culturally Responsive School Intervention for Black Adolescents with Social Anxiety. School Mental Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-024-09658-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-024-09658-6