Abstract

There are numerous tools available to assess coping strategies used by children and adolescents. Many of the existing measures are widely used within diverse settings, often outside of the populations within which the measures were developed. Given the varying use of coping strategies among different populations, there is a need to ascertain the validity and reliability of measurement tools used within particular settings. The current study examines the initial psychometrics of the Self-Report Coping Measure (SRCM), originally developed by Causey and Dubow (J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 21(1): 47–59, 1992), and investigates the psychometric properties of the SRCM in a school-based, low-income, minority urban sample within six elementary schools. Students in 3rd through 8th grade (N = 298) completed the SRCM as part of a larger implementation trial. Confirmatory factor analysis was utilized to assess for fit with four previously validated models of coping factor structure. None provided adequate fit. Consequently, we conducted exploratory analyses, which suggested a three-factor solution with 28 items. Evaluation of convergent validity via correlations with subscales on the Teacher Report Form provided initial support for the validity of the scale. We then examined coping strategy use descriptively in this low-income, school-based population. No differences were found by race/ethnicity or gender; however, children in higher grade levels were less likely to use coping strategies across all factors, including both adaptive and maladaptive strategies. Implications and limitations for use of the SRCM in a low-income, minority school-based population are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

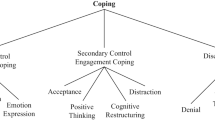

Coping has long been an important focus of study when considering how individuals adjust following stressful events. Coping can be thought of as any response made by a person to reduce or eliminate stressors or psychological distress related to a stressor (Folkman, 1984). The study of coping strategies has gained momentum as researchers seek to understand how coping strategies might be differentially linked to outcomes in adjustment and psychopathology following stressful events. Several models of the link between stress and later psychopathology have been posited, including the diathesis-stress model, which suggests that individual vulnerabilities interact with environmental stressors to trigger the onset of maladjustment or psychopathology (Monroe & Simons, 1991; Richters & Weintraub, 1990), and the differential susceptibility model, which builds on this model to discuss individual responses in both stressful and optimal conditions (Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Boyce & Ellis, 2005; Ellis & Boyce, 2011).

In children, in particular, a large body of work has revealed a complex picture of the relations between coping strategies and later adjustment (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Harding Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001). Generally, responses such as negative emotional expression and denial are thought to be maladaptive and related to higher levels of internalizing symptoms, while other types of responses, such as problem solving and support seeking, have been shown to be more adaptive and associated with lower rates of internalizing symptoms. Still, more recent work suggests a multidimensional and nuanced picture of how coping attenuates the stress-psychopathology link. Boxer, Sloan-Power, Mercado, and Schappell (2012) found that distancing, previously considered an avoidant and thus maladaptive strategy, may be protective for children living in low socioeconomic neighborhoods when faced with stress and violence. A more complex approach was described by Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Henry, Chung, and Hunt (2002) who argued that several coping styles can be functional, but it is the children who have only single coping strategies that fall into at-risk categories. Despite recent advancements in this area, the link between coping strategies and later psychopathology remains unclear, particularly for minority children and adolescents. Thus, continued study of coping remains critically important.

Measurement of Coping

The tools available for the measurement of coping strategies in children are numerous. Compas et al. (2001) and Garcia (2010) discuss the various tools in detail in two of the most comprehensive reviews of measures of coping in children and adolescents. Each measure of coping offers unique advantages and disadvantages with available measures showing great diversity in terms of their format, scope, item content, and foundational models. With respect to format, self-report measures are the most common, likely due to their ease of use (e.g., CCSC; Program for Prevention Research, 1991; A-COPES; Patterson & McCubbin, 1987). While richer data are likely to result from interview formats or observational measures (e.g., the Adolescent Coping Process Interview (ACPI); Feagans-Gould, Hussong, & Keeley, 2007), these are also much more burdensome and much less common than self-report surveys. The least common formats are questionnaires completed by parents, teachers, and peers, perhaps due to concerns regarding the validity of rating internalizing strategies and symptoms by observers (Compas et al., 2001).

Measures used to assess coping in children and adolescents are also varied in terms of their structure, scope, and item content. Compas et al. (2001) reviewed a number of differences, including a discussion of strengths and limitations related to different formats. They noted that measures differ in the extent to which they offer clear and specific choices (e.g., CCCS; Program for Prevention Research, 1991), and whether items refer to coping goals (e.g., “to feel better), such as A-COPES (Patterson & McCubbin, 1987) versus coping strategies (e.g., “distract myself”), such as the Life Events and Coping Inventory (Dise-Lewis, 1988). In addition, although some measures excel at evaluating coping in response to a specific stressor (e.g., the Self-Report Coping Measure; Causey & Dubow, 1992), some measures assess general coping style (e.g., WOC; Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986).

Finally, coping measures are also diverse in their foundational models, with some that were developed empirically and others that have a theoretical basis. Most have been developed based on interviews with children and adolescents or developed to represent theoretical constructs from the extant literature (Compas et al., 2001). Additionally, the theoretical underpinnings of the measures vary widely (Garcia, 2010), including Loevinger’s model of ego development (Loevinger, Wessler, & Redmore, 1970), problem versus emotion-focused coping models (e.g., Folkman & Lazarus, 1980), and the approach-avoid paradigm (Roth & Cohen, 1986).

Psychometric Limitations in the Current Literature

Clearly, coping measures for children and adolescents have historically been numerous and varied in their design and approach. It is unsurprising, then, that these measures are similarly varied in the extent to which they have been psychometrically evaluated. Evaluation of the validity and reliability of a measure is critical to ensuring that the desired construct is measured as it was intended. Without ensuring reliability and validity, researchers are unable to determine whether a scale consistently and accurately measures the construct it is purported to measure, which then impacts the validity of conclusions made from measured data.

Compas et al. (2001) found that a majority of coping measures have not been adequately evaluated with regards to their test–retest reliability. In addition, they noted that tests of construct validity, assessed via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) or via correlations suggesting convergent or discriminant validity, were completed for less than half of the measures that they reviewed. One notable exception to this is the work of Ayers, Sandier, West, & Roosa (1996) who conducted extensive comparative analyses using CFA to evaluate the factor structures of the Children’s Coping Strategy Checklist and the How I Coped Under Pressure Scale. They found that a four-factor model (active coping, distraction, avoidant coping, and support seeking) was a better fit than two other models previously examined in the literature, including a two-factor model (problem- and emotion-focused coping) suggested by Lazarus and Folkman (1984).

However, this careful examination of factor structure is rare. Moreover, the resulting psychometric properties of the instruments that have been evaluated are often mixed (Compas et al., 2001), with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .41 to .92, and factor structure and convergence/divergence with existing measures varying widely. Compas et al. (2001) identified increased attention to reliability and validity of existing measures as a “crucial direction” for future research (p. 107). More recently, Garcia (2010) reviewed coping measures specifically for adolescents and noted a similar lack of psychometric data on measures. Garcia (2010) identifies psychometric evaluation of coping measures within diverse participant groups, in particular, as a key area of need for future research.

The Self-Report Coping Measure

The Self-Report Coping Measure (SRCM; Causey & Dubow, 1992) is a self-report rating scale that was initially developed to address limitations within the available measures at the time. Specifically, the authors hoped to develop a measure that was designed specifically for children and adolescents, psychometrically sound, included a wide range of coping strategies, and assessed cross-situational consistency in children’s coping as well as children’s appraisals of stressors. The theoretical foundations of the SRCM relate back to Roth and Cohen’s (1986) approach/avoidance conceptualization of coping. In the approach orientation, a person employs cognitive or emotional strategies that are oriented toward the stressor, while the avoid style typically refers to cognitive or emotional strategies oriented away from the stressor. Roth and Cohen (1986) went on to describe four sub-factors of avoidance and approach. Avoidance is thought to consist of distancing and emotional reaction, while approach consists of seeking social support and problem solving. Emotional reaction was further broken down into internalizing and externalizing, which are defined as strategies that are oriented inward (e.g., worry or cry) or strategies that are oriented outward (e.g., yell or throw something), respectively (Ebata & Moos, 1991). This resulted in a total of five theoretical subscales: Seeking Social Support, Problem Solving, Distancing, Internalizing, and Externalizing.

Initial psychometric validation of the measure was conducted by Causey and Dubow (1992) in a sample of 481 children in fourth through sixth grade. Children were students in five elementary schools in a semirural community. Participants were overwhelmingly Caucasian, with a makeup up of 85% Caucasian, 8% African American, 5% Latinx, and less than 1% other minority children. The sample was 51.6% male and 48.4% female. Principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to examine the factor structure of the measure. Results suggested a five-factor solution consistent with the five theorized sub-factors. Internal consistencies for subscales ranged from .68 to .84, and the test demonstrated adequate two-week test–retest reliability (Causey & Dubow, 1992).

Use of the SRCM

The SRCM has been a popular choice for the measurement of coping strategies, and researchers have used it in a variety of settings and with different child populations. Consistent with its original development and validation, the SRCM has been used in predominantly Caucasian rural samples (e.g., Roecker Phelps, 2001), although Asarnow, Scott, and Mintz (2002) also utilized the SRCM with Caucasian children from a more urban environment. More diverse populations have also been assessed with the SRCM (e.g., Boxer et al., 2012), including Scott (2003), who investigated coping with respect to discrimination in African American youth. In addition, researchers have used the measure outside of the USA (Andreou, 2001; Ma & Bellmore, 2016) and with college students (Na, Dancy, & Park, 2015). Also, the SRCM has been employed with special populations of children, including maltreated youth (Linning & Kearney, 2004), gifted children (Preuss & Dubow, 2004), and children with chronic illness (Holmbeck et al., 2003).

The SRCM has also been used to target coping in response to a number of specific stressors. In fact, one of the advantages of the SRCM is the ability to tailor the initial prompt to a targeted stressor, allowing for more specific evaluation of coping strategies in response to the specific stressor. Several researchers have edited the prompt to refer to a specific difficulty, such as bullying, aggression, or discrimination (e.g., Andreou, 2001; Roecker Phelps, 2001; Scott, 2003). Although the ability to tailor the initial prompt does allow for flexibility and specificity, it does make the psychometric properties of the measure more complicated to understand and consider. Kochenderfer-Ladd and Skinner (2002) conducted exploratory factor analysis on their adapted version of the measure and found five factors that could be mapped onto Causey and Dubow’s (1992) original factors: Problem Solving, Seeking Social Support, Distancing, Externalizing, and Internalizing. No other studies, however, have examined the factor structure or validity of the adapted measures.

Given the SRCM’s frequent use in diverse settings with varied presenting concerns, it is necessary to have an understanding of the psychometric properties of the measure in samples beyond the predominantly Caucasian, rural sample in which it was initially validated. To date, the factor structure and validity of the measure in a diverse sample remain largely unexplored. Understanding how the SRCM works within diverse communities is of critical importance because it would allow us to better explore a population who has unique stressors and may also have distinct relations among stress, coping, and psychopathology.

Coping in Minority Urban Youth

The use of the SRCM in underserved minority populations is of particular concern given that low-income minority youth experience greater exposure to everyday stressors than their non-minority peers living in higher socioeconomic status communities (Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, 1994; Boardman & Alexander, 2011; Brady & Matthews, 2002). Not only do they tend to experience higher rates of stress, but they are also more likely to experience stressors unique to their low-income minority status, with many of these stressors being chronic and potentially traumatic. For example, low-income minority youth are more likely to experience acculturative stress, economic strain, and discrimination (Thoman & Surís, 2004; Wadsworth, Raviv, Reinhard, Wolff, & Santiago, 2008). In addition, they are far more likely than their non-minority, rural counterparts to live in unsafe neighborhoods, which contributes to increased experiences of violence (Attar et al., 1994).

As a result, researchers have become interested in learning how low-income minority youth cope with stressors and how these coping strategies might attenuate the stress-psychopathology link (e.g., Garbarino, Kostelny, & Dubrow, 1991; Gaylord-Harden, Gipson, Mance, & Grant, 2008). For example, Boxer et al. (2012) found that distancing, previously considered a maladaptive coping strategy, may not be linked to negative outcomes for at-risk youth following exposure to violence. Minority youth have also been found to make use of different coping strategies when compared with non-minority youth. For example, Latinx youth have been found to make more frequent use of social activities and spiritual support compared with their Caucasian counterparts (Copeland & Hess, 1995), while African American youth have been found to use more support seeking than their Caucasian and Latinx peers (Rasmussen, Aber, & Bhana, 2004). When compared with more affluent, non-minority peers, urban, low-income youth tend to utilize coping strategies at different rates, use different coping strategies, and have different outcomes following the use of coping strategies (Boxer et al., 2012; Copeland & Hess, 1995). Other research has indicated that coping patterns are similar across ethnic groups, resulting in uncertainty about whether minority youth cope differently than their Caucasian counterparts (Ayers et al., 1996; Chandra & Batada, 2006).

Given the importance of measuring coping in low-income, minority samples, it is critical that researchers use measurement tools that are known to be valid in this specific population. Unfortunately, measurement of coping among diverse populations has been complicated. For example, the factor structures of at least two commonly used measures of coping (the Ways of Coping Scale and the Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences Scale) have not been replicated when examined in a minority youth sample (Rasmussen et al., 2004; Tolan et al., 2002). Additionally, Gaylord-Harden et al. (2008) were unable to replicate the four-factor structure of the Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist in a sample of African American adolescents. Instead, they found that a three-factor model broken down into active coping strategies, avoidance strategies, and support seeking strategies to be a more appropriate fit.

Current Study

Given that the SRCM was developed in a predominantly Caucasian sample and the established likelihood that youth coping measures might differ across samples, it is imperative that the SRCM be examined further before use with low-income minority children. To our knowledge, no literature has previously examined the factor structure of the SRCM in a low-income minority population. The SRCM has many advantages, including a well-established theoretical basis and a flexible format, and it has been used in diverse populations to date (e.g., Linning & Kearney, 2004). However, the lack of research regarding validity in more diverse samples is problematic. The current study seeks to address this limitation and provide greater understanding about how the SRCM works in low-income minority populations to facilitate research that might shed additional light on the links between stress, coping, and psychopathology in these populations.

In addition, it is critically important that the SRCM be validated for use with a low-income, minority population within urban school settings. Low-income minority youth experience a variety of mental health service disparities and are increasingly receiving services within school settings (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000; Stephan, Weist, Kataoka, Adelsheim, & Mills, 2007). In addition to providing care for children who might not otherwise receive it, school-based mental health services have also been shown to be cost-effective and reduce stigma often associated with mental health care (Taras, 2004). As the interest in both measurement of coping and providing mental health services within schools grows for this population, researchers and practitioners need reliable and valid measures for use in this setting. Thus, it is necessary to explicitly evaluate the SRCM in urban schools.

The goal of the current study was to investigate the psychometric properties of the SRCM in a low-income urban school sample from predominantly ethnic minority backgrounds. Specifically, the first aim of the study was to examine the factor structure of the SRCM. We attempted to replicate the established five-factor structure of the SRCM; however, given the frequency with which coping measures tend to differ in their structures across samples and the significant differences between our urban minority school-based sample and the original sample, we hypothesized that this model would not demonstrate adequate fit. Rather, we hypothesized that the SRCM would have a three-factor structure that would more closely match that of Gaylord-Harden et al. (2008). This model, which included Active Coping Strategies, Avoidance Strategies, and Support Seeking Strategies factors, was validated within a low-income minority sample and, as such, is hypothesized to be a better fit for our data.

The second aim of the study was to further evaluate the psychometric properties of the SRCM in this population. We assessed convergent validity of SRCM factors with a behavioral rating scale completed by teachers. We hypothesized that internalizing and externalizing subscales would correlate significantly with related subscales on the SRCM. Notably, this is the first study to provide a psychometric exploration and initial validation of the SRCM in a low-income minority population in the context of urban schools. Finally, the third aim was to descriptively examine the coping strategies employed by youth in our sample including variation by demographic characteristics. Given research suggesting different coping strategies are utilized more frequently in minority populations, we hypothesized that we would find significant differences among race/ethnicity groups, particularly related to seeking social support. This study sheds important light on coping strategies utilized by urban minority youth in underserved schools.

Method

Setting

The present study was conducted in six elementary or elementary/middle schools in a large urban school district in the northeastern USA. All six schools were located in an impoverished region of the city. One hundred percent of students attending these schools were eligible for subsidized lunch.

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 298 3rd through 8th grade children (mean grade = 4.86, SD = 1.46). 19.3% of children were in the third grade, 27.1% of children were in the fourth grade, 24.3% of children were in the fifth grade, 14.3% of children were in the sixth grade, 7.9% of children were in the seventh grade, and 7.1% of children were in the eighth grade. Children were of predominantly minority race/ethnicity, with 55% Latinx, 30% African American, 14% Multiracial, 1% Caucasian, and .4% Asian American. Sixty-three percent of participants were male. Participants were recruited as part of an implementation trial examining the effectiveness of two training strategies for implementing evidence-based group interventions for anxiety and disruptive behavior in the school setting (Eiraldi et al. 2014). As such, all children participating in our study were identified as having or being at-risk for an anxiety and/or externalizing disorder. Children were screened for the larger study via parent or teacher report using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001), a widely used and psychometrically sound instrument used for the screening of mental health problems in school-age children. Parents of students with elevated scores on the Conduct Problems or Emotional Symptoms subscales of the SDQ were administered a structured diagnostic interview to determine eligibility for the larger study. Children who were enrolled in the larger study and completed baseline measures were included in the current sample.

Children were excluded from the study if they: (a) had a Special Education classification of Intellectual Disability or Autism; (b) were unable to communicate in English; (c) did not have a principal diagnosis or risk of externalizing (Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder) or anxiety (Separation Anxiety Disorder, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, or Social Phobia) disorder; or (d) had an absenteeism rate ≥ 33% for the current school year. Parent measures and diagnostic interviews were offered in both English and Spanish.

Measures

Measures were collected immediately after parent consent and child assent were obtained. Participating children completed the SRCM in one-on-one interview format with an undergraduate research assistant. Research assistants read the measure aloud to individual children in a private location, such as an empty office. Teachers of participating children completed the Teacher Report Form (TRF; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) independently. Teachers were given a $10 debit card for their time completing the questionnaire.

Self-Report Coping Measure for Elementary School Children

The SRCM (Causey & Dubow, 1992) is a 35-item self-report measure used to assess children’s coping strategies and includes scales for Seeking Social Support, Self-Reliance/Problem Solving, Distancing, Internalizing, and Externalizing. The measure consists of an initial prompt to select one of two stressors that the child feels would be most stressful: “having an argument with a friend” or “getting a bad grade in school, one worse than you normally get.” The first 34 items ask respondents to rate the frequency with which they employ coping strategies in response to their selected stressor on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Never to Always. Items include a variety of coping responses, such as “I get help from a friend,” “I yell to let off steam,” and “I say I don’t care.” A final self-efficacy item assesses the extent to which the child feels they had control over the stressful situation (Causey & Dubow, 1992). In the present study, internal consistency measured via Cronbach’s alpha was .77 when including all original items with the exception of the final self-efficacy item.

Teacher Report Form

The Teacher Report Form (TRF) is a 118-item standardized rating scale with well-validated psychometric properties that provides a measure of children’s (age 6 to 18 years) internalizing and externalizing difficulties, as well as social and academic competencies, as reported by the child’s teacher (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000). The present study investigated relevant subscales from the TRF. In terms of overall problem-oriented scales, we utilized the Externalizing Problems and Internalizing Problems scales. In addition, we examined the following symptom subscales: Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, and Rule-Breaking Behavior. Finally, we investigated the following DSM-IV categories: Anxiety Problems, Somatic Problems, Oppositional Defiant Problems, and Conduct Problems.

Missing Data

Missing data was minimal with 2.4% of participants missing data for the SRCM. Means comparisons for those who had complete SRCM data and those who had incomplete data were conducted using ANOVA to test for bias in the missing data, and no significant differences emerged. Given the low percentage of missing data in the sample and apparent lack of evidence for bias related to the missingness, listwise deletion was utilized.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In order to investigate the factor structure and psychometric properties of the SRCM in a low-income, minority, school-based sample, we first utilized confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). CFA models were fit to the data using the lavaan package in R version 3.5.3 and a weighted least squares means and variance adjusted estimator. Item loadings were freely estimated. As recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999), the fit of each model was assessed using a combination of goodness-of-fit indices, including Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; Tucker & Lewis, 1973), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Steiger & Lind, 1980), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Values approaching or greater than .95 on CFI and TLI, an RMSEA nearing .06 or below, and an SRMR close to .08 or below were used as cutoffs for adequate-to-good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kenny & McCoach, 2003).

The first CFA model was analyzed to assess whether the factor structure of the SRCM in our sample was similar to that of the SRCM in the original, predominantly Caucasian sample. Analyses were conducted utilizing the first 34 items, which assessed frequency of coping strategy use, and did not include item 35, which assessed whether participants felt they could change their situation (a self-efficacy item) in order to be consistent with the data analytic strategy used by Causey and Dubow (1992). As noted previously, this model included five factors: Seeking Social Support, Problem Solving, Distancing, Internalizing, and Externalizing. Details regarding which items were loaded onto each factor can be found in Table 1. The five-factor model of the SRCM did not demonstrate good fit in our sample. Model fit statistics were as follows: CFI = .88, TLI = .87, RMSEA = .051, SRMR = .084.

Given that this model did not demonstrate adequate fit, we then evaluated whether a three-factor model as posited by Gaylord-Harden et al. (2008) might be a better fit given that the model was validated within a low-income minority sample, albeit with a different measure. This model consisted of three factors: Active Coping Strategies, Avoidance Strategies, and Support Seeking Strategies (see Table 1 for items in each factor). The fit of this model was also inadequate (CFI = .81, TLI = .79, RMSEA = .066, SRMR = .098).

Finally, in an effort to thoroughly evaluate whether the data from the current sample might fit an already established coping model, we examined two additional model structures: a four-factor model (Ayers et al., 1996) and a two-factor model (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). We chose to test using the model examined by Ayers and colleagues because it was evaluated within a racially and ethnically heterogeneous school-based sample with children from lower-middle to middle income and replicated across two different samples (Ayers et al., 1996). The Folkman and Lazarus (1980) two-factor model was also selected because it is a foundational model upon which many coping measures have been based, and it allows for evaluation of a model with fewer broader categories.

In the first of the two models, Ayers and colleagues broke coping strategies down into four factors: Active Coping Strategies, Distraction Strategies, Avoidance Strategies, and Support Seeking Strategies. Fit statistics for this model were the following: CFI = .80, TLI = .79, RMSEA = .067, SRMR = .097, suggesting that the model did not have adequate fit. Finally, the Folkman and Lazarus (1980) model, which suggests Emotion-Focused and Problem-Focused factors, did not demonstrate good fit for the data (CFI = .87, TLI = .86, RMSEA = .052, SRMR = .088). Please see Table 1 for additional details regarding how items were mapped onto factors.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Given that our attempts to confirm an existing factor structure were unsuccessful, we decided to take an exploratory approach to examine the structure of the SRCM in our sample utilizing exploratory factor analysis (EFA). EFA is recommended when an investigator wishes to find “the most parsimonious explanation” of the correlation matrix variance rather than to confirm an a priori hypothesis regarding factor structure (Tinsley & Tinsley, 1987, p. 419).

Consistent with the methodology used by Causey and Dubow (1992), we conducted principal components analysis with varimax rotation on all factors satisfying Kaiser’s criterion. The model was fit using the psych package in R version 3.5.3. This resulted in a three-factor solution consisting of 28 items. Of the initial 34 items (excluding the self-efficacy item), six were dropped from the measure. One item (Item 3) was removed due to cross loading between factors two and three. Four items with factor loadings lower than .3 were removed, which is consistent with a standard benchmark used for eliminating variables that do not substantially contribute to the overall factor (Tinsley & Tinsley, 1987). Finally, one item (Item 24) was removed as it only marginally contributed to the second factor with a factor loading of − .31, and it was not theoretically consistent with all other items on the factor. The solution resulted in 28 items, with three factors.

Factor loadings ranged from .35 to .76. See Table 2 for item loadings and distribution of items across factors. Based on item distribution, factors could be described theoretically as follows: “Approach,” “Externalizing,” and “Internalizing.” The Seeking Social Support and Problem solving factors found by Causey and Dubow (1992) in their original analysis of the SRCM were collapsed into the higher-order Approach factor in our analysis. In addition, a fifth factor resembling the Distancing factor found by Causey and Dubow (1992) in their original analysis of the SRCM was not found. Several items that originally fell under Distancing were grouped in the Externalizing factor in our sample, and a few items did not have strong loadings on any factor in our solution and thus were omitted.

Establishing Reliability and Validity

Cronbach’s alpha for this 28-item version of the scale was .78. Internal consistencies for the Approach factor, Externalizing factor, and Internalizing factor were .87, .79, and .61, respectively. To examine validity, we created factor scores by calculating the mean of all items within each newly identified factor. Descriptive statistics for these factor scores are listed in Table 3. Bivariate correlations among the Externalizing and Internalizing factor scores and relevant subscales on the TRF suggested significant positive correlations for the Internalizing factor with the TRF’s Internalizing Problems and for the Externalizing factor with Externalizing Problems. In addition, the Internalizing factor was positively correlated with the Anxious/Depressed, and Anxiety Problems subscales, while the Externalizing factor was marginally positively associated with the Anxious/Depressed subscale and significantly positively associated with the Social Problems subscale. Both factors had marginal positive associations with the Rule-Breaking Behavior subscale. Finally, the Externalizing factor had a marginal positive relation with the Oppositional Defiant Problems subscale. Please see Table 4 for a full list of correlations with all TRF subscales.

Coping Strategies by Demographic Characteristics

To investigate differences in use of coping strategies by race/ethnicity, we conducted a one-way ANOVA for each coping factor. No significant differences emerged by race/ethnicity. T tests were conducted to assess for differences by gender. No significant differences for any coping factor were found. With respect to grade, t tests showed significant differences when children from higher grades (6th–8th) were compared with children from lower grades (3rd–5th) for all factors. Specifically, children in higher grades (M = 3.06, SD = .82) were significantly less likely to use approach-based coping strategies than children in lower grades (M = 3.37, SD = .84; t(273) = − 2.80, p = .006). Children in higher grades (M = 2.76, SD = 1.05) were also significantly less likely to externalizing coping strategies than children in lower grades (M = 3.49, SD = .97; t(273) = − 5.52, p < .001), and children in higher grades (M = 2.86, SD = 1.01) were again significantly less likely to use internalizing coping strategies than children in lower grades (M = 3.17, SD = .94; t(273) = − 2.41, p = .016).

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to investigate the psychometric properties of the SRCM in a low-income, minority urban school sample. First, we investigated the factor structure to assess whether its structure as shown by Causey and Dubow (1992) in a largely white, semirural sample, differed in an urban school-based, minority population. We first attempted to replicate the original structure; however, CFA revealed that this model structure was a not a good fit for our data. This result suggests that this theoretical structure was not a good match for the measured coping strategies of low-income urban children in a school setting. In particular, it appeared that the Distancing factor was not a good fit for our sample as item loadings on this factor were particularly low (.17–.66).

We then attempted to test our hypothesis that the factor structure of our measure might be a better match with three other existing theoretical frameworks: a three-factor model examined by Gaylord-Harden et al. (2008), a four-factor structure evaluated by Ayers et al. (1996), and a two-factor model developed by Folkman and Lazarus (1980). We hypothesized, in particular, that the three-factor model including Active Coping Strategies, Avoidance Strategies, and Support Seeking Strategies, would be a good fit for our data as it was validated in a low-income minority youth sample. Still, none of these previously established models were an adequate fit for our data based on CFA results. Our results indicate that the data from low-income urban children in our current sample did not fit any pre-established theory.

As a result, we opted to conduct exploratory analyses to investigate the factor structure of the SRCM in greater detail. Results suggested that the measure was best broken down into three factors that did have notable similarities to factors established in the initial structure: Approach, Externalizing, and Internalizing. Like the original factor structure, our model included two separate factors for externalizing and internalizing coping strategies. None of the other models tested had externalizing and internalizing factors, which may have contributed to poor fit with CFA. Our exploratory analyses also revealed an Approach factor, which is similar to the initial model’s Seeking Social Support and Problem Solving factors, although combined into one factor. All but one item (Item 34: I will talk to the teacher about it) that originally loaded on these two factors in the Causey and Dubow model loaded on the Approach factor in our analysis. Perhaps in our current sample, there is a less of a distinction between these “approach-style” coping strategies than in a sample of semirural Caucasian children. It is also interesting to note that Item 34 was a better fit under the Internalizing category. It is difficult to say exactly why this might be, but it is possible that this is related to differences in the tendency of children in low-income, predominantly minority, urban schools to go to teachers for support. Morris (2010) described a culture of “anti-snitching” and a distrust of formal authority that tends to be more common in these schools when compared to largely Caucasian rural schools. This cultural difference may have contributed to this unexpected finding.

As coping measures often have variable factor structures from sample to sample (Compas et al., 2001), it is especially interesting that the factor structure of the SRCM in this low-income, minority, school-based sample shared significant similarities with that of the originally validated measure in semirural Caucasian population. This could suggest that, in our sample, this scale operates more like it did in this original sample than we initially expected. Still, despite these similarities, there were important differences. Most notably, the fifth factor found in the original validation, Distancing, was not found in this study. In fact, only two of the items originally found to be a part of the original Distancing factor loaded cleanly onto any factor in the current study or had factor loadings above .3. This suggests that these items as well as the Distancing factor overall were not as relevant in a low-income, minority, urban school population.

It is possible that these coping strategies, such as, “I forget the whole thing,” or, “I make believe it didn’t happen,” are used less frequently by this population or that, when they are used, they do not clearly represent a category of distancing or avoidant coping. Another possibility is that some of these coping strategies may be more adaptive in a minority, urban school sample than in a largely semirural Caucasian sample and thus may not be loading together on any one factor. As noted previously, Boxer et al. (2012) have provided support for the notion that distancing strategies may be uniquely adaptive in a low-income sample with a high degree of stress. This may have caused these items to be interpreted differently in our population or for the items simply to have performed unexpectedly. In addition, children were prompted to respond to either mild peer or academic stressors, which might not be salient stressors in the current population given our sample’s high level of exposure to more severe/chronic stressors. The selection of a more severe stressor (e.g., neighborhood violence, poverty) may have yielded a different factor structure or resulted in the final inclusion of different items.

Despite the reduction in measure length, the internal consistency of the shortened scale remained adequate. This presents an important advantage for use in underserved schools where limited time and resources may prohibit the use of longer measures.

Validity of the Factors

The second aim of the current study was to assess for convergent validity of the SRCM factors. Specifically, we compared the Internalizing and Externalizing factors with relevant subscales from the TRF. Results suggested significant relations in expected directions with most relevant subscales. The Internalizing factor was significantly positively related to a number of TRF subscales measuring overall internalizing symptoms and specific internalizing syndrome subscales such as anxiety and depression. This provides initial evidence that the Internalizing factor is, in fact, a valid representation of internalizing coping strategies, which theoretically align with broad internalizing symptoms. Similarly, the Externalizing factor was significantly related in the expected direction with most externalizing subscales of the TRF, including overall externalizing symptoms and specific symptoms such as social problems. This provides some support for the convergent validity of the Externalizing factor given the theoretical overlap between externalizing symptoms and externalizing coping strategies.

However, the Internalizing and Externalizing factors were not significantly correlated with some TRF subscales as expected, including the Anxiety Problems subscale for Internalizing and the Oppositional Defiant Problems (marginal result) and Conduct Problems subscales. Furthermore, there were a few marginal associations that were unexpected. Specifically, the Externalizing factor was marginally linked with the Anxious/Depressed subscale, and the Internalizing factor was marginally linked with the Rule-Breaking Behavior subscale. It is unclear why a factor assessing externalizing coping strategies was associated with TRF subscales that are more apparently related to internalizing behaviors and vice versa; however, it may be due to high levels of comorbidity between internalizing and externalizing behavior difficulties in this population. In addition, the items may not clearly identify strategies traditionally considered to be “externalizing.” Item 7 (“I go off by myself”), in particular, may be more closely aligned with an internalizing style. As noted previously, this item originally loaded onto the Internalizing factor during initial validation of the measure by Causey and Dubow (1992). These results suggest that the validity of these factors requires further investigation, despite some evidence suggesting that the factors represent externalizing and internalizing coping strategies as expected.

Descriptive Examination of Coping Strategy Use in a School-Based, Minority Sample

Our final aim was to examine the coping strategies employed by youth in our school-based sample descriptively. Given the growing interest in coping strategies of youth in low-income minority samples, these findings provide important insight. These findings are also important because they provide information on these youth with one of the only coping measures to be psychometrically evaluated for use in this population and setting. We hypothesized that there would be significant differences among racial/ethnic groups based on findings from previous studies. We did not expect differences based on gender or grade. Unexpectedly, there were no differences in utilization rates of coping strategies by race/ethnicity. Regardless of race/ethnicity, children in this school-based sample appeared to utilize different coping strategies at similar rates, which differs from previous research suggesting that African American children tend to use support seeking at a higher rate than their Latinx and Caucasian counterpoints (Rasmussen et al., 2004). However, we may have been less likely to detect this difference given that the factor structure of the SRCM included one broad Approach factor rather than a specific support seeking factor.

Results also suggested that children in more advanced grades were also less likely than their peers in lower grades to implement coping strategies of all types, including those that are typically considered adaptive (approach-style strategies such as seeking support and problem solving) and those typically considered maladaptive (externalizing and internalizing). This information is helpful when considering intervention planning within the school setting. For example, perhaps younger children should be targeted for additional assistance to reduce use of maladaptive externalizing and internalizing coping strategies, while older children might be targeted to increase use of problem solving and social support seeking coping strategies. In general, it might be helpful to develop coping interventions that focus on both decreasing maladaptive coping strategies and increasing adaptive coping strategies, as results from this study suggest that lower rates of maladaptive strategies do not necessarily correlate with higher rates of adaptive strategies. No gender differences in coping strategy use emerged.

Implications for Clinical Use of the SRCM in Underserved Schools

This study provides important insight regarding the use of the SRCM in an urban, minority population in an underserved school setting. It is particularly promising as so few coping measures are validated for use in this context, and interest continues to grow in measuring coping of minority youth in urban schools. As described previously, low-income minority youth are disproportionately more likely to experience a high degree of stressors as well as chronic stressors and thus are more likely to require evaluation and intervention related to coping with stressors. Moreover, low-income minority youth are increasingly being evaluated and receiving services integrated within school settings. This combination of factors makes the demand for a psychometrically valid measure in this particular population and setting quite high, and very few measures have been evaluated for use in this way. As such, the SRCM may be one the best options for understanding coping in this population currently available.

Results from this investigation provide initial support for this modified version of the SRCM in underserved schools for minority youth. The shorter length of the scale may be particularly helpful as personnel in these schools may have less time and resources to screen children. In addition, although we evaluated the scale with the original stressor prompts utilized by Causey and Dubow (1992), the prompts could be altered to better match typical stressors for low-income, minority children, such as community violence or discrimination. This flexibility would be a valuable asset in working with this population. As discussed below, further research would be needed to evaluate the SRCM with these adjusted stressor prompts.

Limitations

Despite showing initial promise, additional steps should be taken to provide supplementary data for those seeking to utilize the SRCM in school-based settings with low-income minority students. First, further validation of the factor structure is required. EFA is limited in that it is driven by data from a particular sample, and thus the results may not be able to be generalized beyond that sample. Confirmatory factor analysis should be employed to verify the proposed model, and additional work should be done to further validate the factors. In addition, this study was limited in that it does not examine the validity of the Approach factor. With limited resources in the context of a larger study, we were not able to collect data that would have provided opportunities for analyses that might have provided validation of these scales. Ideally, future research would both confirm factor structure and provide better insight into the validity of each of the proposed factors.

Limitations related to the stressor prompts should also be noted. While it is a strength of the study that the factor structure was evaluated in the context of stressors prompts identical to the original measure to allow for better comparison, it is true that these stressors might not have been salient for this population, as noted above. Typical stressors for low-income, minority children differ dramatically from those experienced by semirural Caucasian children, and they are much more likely to be chronic and/or traumatic in nature. It is certainly possible that a more salient stressor for this population might yield a different factor structure. This warrants further investigation. In addition, we were not able to compare coping strategies utilized based on which prompt participants selected as detailed information about which prompts were selected was unavailable. It should be noted that factor structure in the original measure was invariant regardless of prompt selected (Causey & Dubow, 1992).

Finally, additional research may be needed to expand the scope of this work. The current sample consisted of students referred for behavioral or emotional problems. This measure should ideally be tested on a universal population to increase generalizability. Similarly, generalizability was limited by the age range of the current sample (3rd–8th grade). Further research is needed to extend these results beyond this age group. Additional research to address these limitations and extend the current investigation would allow for increased confidence when using the SRCM with low-income, minority youth in urban schools.

Future Directions

Future research should focus on both addressing limitations of the current study and further exploring the psychometric properties of the SRCM in low-income, minority populations. As noted above, future studies should focus on providing additional data regarding the validity of factors. Future studies should also ideally conduct confirmatory factor analysis in a similar population to test our proposed factor structure. In addition, it would be helpful to expand the study sample to include a wider range of ages and different urban populations. Other helpful avenues for future research would include establishing test–retest reliability of the SRCM and exploring how altering the stressor prompts impacts the psychometrics of the SRCM, particularly in a disadvantaged, minority, school-based population. A particularly interesting approach would be to evaluate the psychometric properties using stressor prompts that were developed in collaboration with community stakeholders (e.g., teachers, parents and students) to ensure relevance to the population. Finally, given difficulties disentangling the roles of grade and race/ethnicity in predicting use of social support as a coping strategy, additional research investigating individual predictors of coping strategy use is warranted.

With the addition of this future research, the scientific community would be much closer to establishing a well-validated coping measure for low-income, minority youth in urban schools. Researchers and clinicians alike have demonstrated a number of uses for the measurement of coping within school settings, ranging from academic questions of predictors and sequelae to applied concerns of screening and treatment progress monitoring. As interest in learning about coping within this high-risk population has grown, and the demand for services for these children integrated within school settings has grown alongside it, the need for a psychometrically sound coping measure has become paramount. While further research on this and other coping measures in this particular setting remains necessary, this investigation provides important initial support for the SRCM in this unique context.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Andreou, E. (2001). Bully/victim problems and their association with coping behaviour in conflictual peer interactions among school-age children. Educational Psychology,21(1), 59–66.

Asarnow, J. R., Scott, C. V., & Mintz, J. (2002). A combined cognitive–behavioral family education intervention for depression in children: A treatment development study. Cognitive Therapy and Research,26(2), 221–229.

Attar, B. K., Guerra, N. G., & Tolan, P. H. (1994). Neighborhood disadvantage, stressful life events and adjustments in urban elementary-school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology,23(4), 391–400.

Ayers, T., Sandier, I., West, S., & Roosa, M. (1996). A dispositional and situational assessment of children’s coping: Testing alternative models of coping. Journal of Personality,64(4), 923–958.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis-stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influence. Psychological Bulletin,135, 885–908.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin,107, 238–246.

Boardman, J. D., & Alexander, K. B. (2011). Stress trajectories, health behaviors, and the mental health of black and white young adults. Social Science and Medicine,72(10), 1659–1666.

Boxer, P., Sloan-Power, E., Mercado, I., & Schappell, A. (2012). Coping with stress, coping with violence: Links to mental health outcomes among at-risk youth. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment,34(3), 405–414.

Boyce, W. T., & Ellis, B. J. (2005). Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-development theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology,17, 271–301.

Brady, S. S., & Matthews, K. A. (2002). The influence of socioeconomic status and ethnicity on adolescents’ exposure to stressful life events. Journal of Pediatric Psychology,27(7), 575–583.

Causey, D. L., & Dubow, E. F. (1992). Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology,21(1), 47–59.

Chandra, A., & Batada, A. (2006). Exploring stress and coping among urban African American adolescents: The shifting the lens study. Pre-venting Chronic Disease,3, 1–10.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin,127(1), 87.

Copeland, E. P., & Hess, R. S. (1995). Differences in young adolescents’ coping strategies based on gender and ethnicity. The Journal of Early Adolescence,15(2), 203–219.

Dise-Lewis, J. E. (1988). The life events and coping inventory: An assessment of stress in children. Psychosomatic Medicine,50, 484–499.

Ebata, A. T., & Moos, R. H. (1991). Coping and adjustment in distressed and healthy adolescents. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology,12(1), 33–54.

Eiraldi, R., McCurdy, B., Khanna, M., Mautone, J., Jawad, A. F., Power, T. J., et al. (2014). A cluster randomized trial toevaluate external support for the implementation of positive behavioral interventions and supports by school personnel. Implementation Science, 9, 12.

Ellis, B. J., & Boyce, W. T. (2011). Differential susceptibility to the environment: Toward an understanding of sensitivity to developmental experiences and context. Development and Psychopathology,23, 1–5.

Feagans Gould, L., Hussong, A. M., & Keeley, M. L. (2007). The adolescent coping process interview: Measuring temporal and affective components of adolescent responses to peer stress. Journal of Adolescence,31(5), 641–657.

Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,46(4), 839.

Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,21(3), 219–239.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Dunkel-Schetter, C., DeLongis, A., & Gruen, R. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,50, 571–579.

Garbarino, J., Kostelny, K., & Dubrow, N. (1991). What children can tell us about living in danger. American Psychologist,46, 376–383.

Garcia, C. (2010). Conceptualization and measurement of coping during adolescence: A review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship,42(2), 166–185.

Gaylord-Harden, N., Gipson, P., Mance, G., Grant, K., & Strauss, Milton E. (2008). Coping patterns of African American adolescents: A confirmatory factor analysis and cluster analysis of the children’s coping strategies checklist. Psychological Assessment,20(1), 10–22.

Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,40(11), 1337–1345.

Holmbeck, G. N., Westhoven, V. C., Phillips, W. S., Bowers, R., Gruse, C., Nikolopoulos, T., et al. (2003). A multimethod, multi-informant, and multidimensional perspective on psychosocial adjustment in preadolescents with spina bifida. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,71(4), 782.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling,6, 1–55.

Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling,10, 333–351.

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Skinner, K. (2002). Children’s coping strategies: Moderators of the effects of peer victimization? Developmental Psychology,38(2), 267.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company.

Linning, L. M., & Kearney, C. A. (2004). Post-traumatic stress disorder in maltreated youth: A study of diagnostic comorbidity and child factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence,19(10), 1087–1101.

Loevinger, J., Wessler, R., & Redmore, C. (1970). Measuring ego development (Vol. 2). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ma, T. L., & Bellmore, A. (2016). Connection or independence: Cross-cultural comparisons of adolescents’ coping with peer victimization using mixed methods. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,47(1), 109–130.

Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin,110, 406–425.

Morris, E. (2010). “Snitches end up in ditches” and other cautionary tales. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice,26(3), 254–272.

Na, H., Dancy, B. L., & Park, C. (2015). College student engaging in cyberbullying victimization: Cognitive appraisals, coping strategies, and psychological adjustments. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing,29(3), 155–161.

Patterson, J. M., & McCubbin, H. L. (1987). Adolescent coping style and behaviors: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Adolescence,10, 163–186.

Preuss, L. J., & Dubow, E. F. (2004). A comparison between intellectually gifted and typical children in their coping responses to a school and a peer stressor. Roeper Review,26(2), 105–111.

Program for Prevention Research. (1991). Family influences survey documentation. Unpublished manuscript. Program for Prevention Research, Arizona State University, Tempe, March 1991.

Rasmussen, A., Aber, M. S., & Bhana, A. (2004). Adolescent coping and neighborhood violence: Perceptions, exposure, and urban youth’s efforts to deal with danger. American Journal of Community Psychology,33, 61–75.

Richters, J., & Weintraub, S. (1990). Beyond diathesis: Toward an understanding of high-risk environments. In J. Rolf, A. Masten, D. Cicchetti, et al. (Eds.), Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology (pp. 67–96). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Roecker Phelps, C. E. (2001). Children’s responses to overt and relational aggression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology,30(2), 240–252.

Rones, M., & Hoagwood, K. (2000). School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review,3, 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026425104386.

Roth, S., & Cohen, L. J. (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist,41(7), 813.

Scott, L. D., Jr. (2003). The relation of racial identity and racial socialization to coping with discrimination among African American adolescents. Journal of Black Studies,33(4), 520–538.

Steiger, J. H., & Lind, J. C. (1980). Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychometric Society, Iowa City, IA, May 1980.

Stephan, S. H., Weist, M., Kataoka, S., Adelsheim, S., & Mills, C. (2007). Transformation of children’s mental health services: The role of school mental health. Psychiatric Services,58, 1330–1338.

Taras, H. L. (2004). School-based mental health services. Pediatrics,113, 1839–1845.

Thoman, L. V., & Surís, A. (2004). Acculturation and acculturative stress as predictors of psychological distress and quality-of-life functioning in Hispanic psychiatric patients. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences,26(3), 293–311.

Tinsley, H. E., & Tinsley, D. J. (1987). Uses of factor analysis in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology,34(4), 414.

Tolan, P. H., Gorman-Smith, D., Henry, D., Chung, K. S., & Hunt, M. (2002). The relation of patterns of coping of inner–city youth to psychopathology symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence,12(4), 423–449.

Tucker, L., & Lewis, R. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika,38(1), 1–10.

Wadsworth, M. E., Raviv, T., Reinhard, C., Wolff, B., Santiago, C. D., & Einhorn, L. (2008). An indirect effects model of the association between poverty and child functioning: The role of children’s poverty-related stress. Journal of Loss and Trauma,13(2–3), 156–185.

Funding

The study was funded by The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (R01 HD073430).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The senior author has received research funding from NICHD. No other authors have conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Swift, L.E., Orapallo, A., Kanine, R.M. et al. The Self-Report Coping Measure in an Urban School Sample: Factor Structure and Coping Differences. School Mental Health 12, 99–112 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09332-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-019-09332-2