Abstract

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) originating in the duodenal wall constitute the most challenging localization of this gastrointestinal neoplasm. Duodenal GISTs are relatively uncommon. The prevalence of duodenal GIST is very low, accounting for 5% to 7% or less of all surgically resected GISTs. Most published reports on duodenal GIST are case reports or small case series. Consequently, the unspecific clinical manifestations, radiologic diagnosis, appropriate surgical treatment, prognostic factors, and survival constitute a subject of current controversy. This review addresses the management of duodenal GISTs trying to establish and define surgical options according to GIST localization within the duodenum. Most articles concerning duodenal GISTs state that unlike tumors involving other sites of the gastrointestinal tract, the optimal procedure for duodenal GISTs has not been well characterized in the surgical literature. However, when carefully reviewing the published literature on the subject, it was possible to identify common surgical approaches to duodenal GISTs which are fairly standard among different authors. All approaches take into account the GIST localization within the duodenal wall and its anatomic relationships to decide whether local resection or the Whipple operation should be performed. Using this knowledge, defined surgical options for duodenal GISTs according to their localization within the duodenum are being proposed. Besides the current controversy regarding the indications for the Whipple procedure, the other most important issue remaining to be addressed is the implementation of laparoscopic surgery for this challenging tumor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are defined as morphologically spindle cell, epithelioid, occasionally pleomorphic, and mesenchymal tumors that usually arise from the gastrointestinal tract, express the KIT protein (c-kit), have a positive immunohistochemistry staining for CD117, and harbor a mutation of a gene that encodes for a type III receptor tyrosine kinase [1]. GISTs are known as such since 1983 [2]. In 1998, the role of c-kit in the pathology of GIST was defined [3], and in 2001, a major finding concerning the activity of imatinib mesilate against GIST was reported [4]. The current management of GIST includes surgery for local non-metastatic tumors and a combination of imatinib and surgery for recurrent or metastatic GIST. Indications for imatinib therapy, besides recurrence and metastasis, are still controversial [1, 5]. Recommended imaging studies include computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) [5, 6]; however, CT is more widely available and is the imaging modality of choice for patients with suspected or biopsy-proven GIST [5]. The incidence of GISTs varies from 10 to 20 cases per million people per year [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. GISTs are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract, accounting for 1% to 2% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. GISTs can occur in any part of the digestive tract and are more common in the stomach (50% to 70%), followed by the small bowel (20% to 30%); colon, rectum, and appendix (0.5% to 10%); esophagus (1%); and some rare cases of extra-gastrointestinal GISTs located in the pancreas, gallbladder, mesentery, greater and lesser omentum, and retroperitoneum (1.5% to 5%) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Duodenal GISTs are relatively uncommon, and their prevalence is very low accounting for 5% to 7% or less of all surgically resected GISTs. However, they represent nearly 30% of all primary duodenal tumors [7]. Most publications on duodenal GIST are case reports or small case series [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Consequently, the unspecific clinical manifestations, radiologic diagnosis, appropriate surgical treatment, prognostic factors, and survival constitute a subject of controversy. This review addresses the current management of duodenal GISTs defining surgical options according to GIST location within the duodenum.

Biology of GIST

GISTs are neoplasms arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal which form a cellular network around the myenteric plexus and within the muscularis propria of the gastrointestinal wall [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Most GISTs are comprised of a fairly uniform population of spindle cells (70% of cases), others are dominated by epithelioid cells (20% of cases), and the remainder 10% consist a mixture of spindle and epithelioid cells [8, 9]. The cell morphology varies by site and by the type of mutation of the KIT and the platelet-derived growth factor receptors-α (PDGFR-α) genes. GISTs with PDGFR-α mutations are nearly exclusive gastric in origin and are mostly the epithelioid variants [10,11,12]. Approximately 86% to 95% stain positively for c-kit (CD117), 80% for BCL-2, 70% to 81% for CD34, 35% to 70% for smooth muscle actin, 10% to 38% for S-100, and 5% or less for desmin [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. A recently characterized gene encoding DOG1 protein has been stained by the anti-DOG1 antibody and has been found useful in staining GISTs possessing either KIT or PDGFR-α mutations [10]. KIT mutation is an early event in GIST development [10]. Either KIT or PDGFR-α mutations are found in over 95% of adult GISTs [10, 11]. KIT, encoded by the c-kit gene, is a 145-kD transmembrane glycoprotein member of the subclass III family of receptor tyrosine kinases that serves as receptor for SCF and tyrosine kinase and is structurally similar to PDGFRs-α and -β, colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor (CSF-1R), and FMS-like tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT-3) [9, 10]. Mutations of the juxtamembrane domain or exon 11 have been reported with a frequency between 20 and 92%; however, the incidence is around 66%. Mutations in the extracellular domain or exon 9 are most frequent in small bowel GISTs (95%) and have been found in 10% to 18% of all cases. In approximately 10%, no KIT mutations are found even if the whole coding region is examined [10]. Most duodenal GISTs have mutations of exon 11 (40% to 70%), and other frequently found mutations were located on exon 9 (13% to 31%) and exon 13 (11%). The importance of KIT mutations lies in the prognosis associated to more aggressive mutations such as the mutations of exon 11 which are present in high-risk GISTs, while mutations of exon 9 have been related to malignant GISTs [9] (Table 1).

Clinical Presentation

GISTs have been diagnosed in all-age patients, but most tumors show clinical manifestations around 60 years of age. They are more frequent in male patients (68% to 80%) [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Because of the lack of specific clinical manifestations, early detection of duodenal GISTs is difficult. At the time of diagnosis, most tumors may have caused mass-related symptoms or anemia as a result of hemorrhage secondary to mucosal ulceration [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Duodenal GISTs are frequently asymptomatic lesions and are discovered incidentally during radiologic imaging for unrelated conditions and during elective or emergency surgery for other causes [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. Duodenal GISTs most frequently involve the second portion of the duodenum, followed in order by the third, fourth, and first duodenal portion [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20] (Table 2). Despite the fact that the duodenum is an uncommon location for the occurrence of GIST and the prevalence is around 5% or less [7, 18], some authors have reported an incidence between 6 and 29% in series comprising GISTs in all locations and series of GISTs located specifically in the small bowel [16, 17, 19]. GISTs present with abdominal pain, palpable abdominal mass, bowel obstruction, intussusception, volvulus, perforation, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage [23, 29,30,31]. The most common symptoms of duodenal GISTs are hemorrhage and abdominal pain [17,18,19,20]. However, many are asymptomatic (Table 3). Most duodenal GISTs are endophytic measuring 5 cm or less and present with upper digestive hemorrhage, either macroscopic or occult [18,19,20,21]. Abdominal pain is more likely to be present in large exophytic tumors and is due to mass effect and compression on other organs [19]. According to the established criteria for risk of progression [22] (Table 4), duodenal GISTs represent very low risk in 8%, low risk in 31%, and high risk in 69% [21]. At the time of presentation, most tumors are solitary (89%) [19].

Duodenal GIST in Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type I

GISTs have been described in the setting of Carney’s triad, Carney-Stratakis syndrome, and neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) [9, 10, 21,22,23, 29]. Most GISTs are generally sporadic, but 5% occur in the context of a familial syndrome and NF1 [21]. Patients with NF1 have a high risk to develop GISTs (7%) [23]. In familial GIST, remarkable hyperplasia of the interstitial cells of Cajal is observed in the small and large intestines [10]. Duodenal GISTs are an uncommon occurrence in NF1. Based on retrospective reviews and postmortem examination studies, some have estimated that 10% to 60% of patients with NF1 have gastrointestinal tumors, although less than 5% actually have any associated symptomatology [29]. In these patients, GISTs are frequently multifocal and multiple with some tumors being benign and others malignant, and they are habitually located in the small bowel, more commonly in the ileum [23, 29,30,31]. NF1 is one of the most common genetic disorders, inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance, and the abnormality has been localized to the long arm of chromosome 17 (17q11.2) [23, 29,30,31]. This gene encodes neurofibromin, a cytoplasmic protein which controls cellular proliferation by inactivating the p21 ras and the MAP kinase pathway [30]. The type of GIST developing in NF1 results from the inactivation of neurofibromin; since neurofibromin suppresses the ras-MAP kinase cascade, the cause of GIST in NF1 appears to be hyperactivation of the ras-MAP kinase cascade [10].

Diagnosis

Endoscopy

The first and second portions of the duodenum are accessible by conventional endoscopy. Most duodenal GISTs located within the first and second duodenal portion can be detected with endoscopy [17]. At endoscopy, GISTs appear as submucosal sharply demarcated elevated tumors, occasionally ulcerated [7, 18, 21]. Sometimes, small, less than 2 cm ulcerated duodenal GISTs have been mistaken by the papilla of Vater, and hemobilia has been suspected [18]. Endoscopic biopsy rarely yields a correct diagnosis and most times shows only chronic inflammation or normal mucosa; however, some have reported an accuracy of 21% to correctly diagnose duodenal GISTs [7].

Computed Tomography

The best radiologic study to identify and diagnose duodenal GISTs is abdominal computed tomography (CT). Practically all duodenal GISTs can be detected by CT [17, 18]. GISTs are hypervascular tumors appearing as well-defined endophytic or exophytic masses on contrast-enhanced images, the tumor is strongly enhanced in the arterial phase, and this enhancement may last until the delayed venous phase [15, 32, 33]. Large tumors tend to have mucosal ulceration and present as well-enhanced, well-demarcated, lobulated, heterogeneous mass which may have central necrosis and cavitation with cystic and necrotic components combined with intraluminal and extraluminal tumor growth [7, 17, 32,33,34,35]. Small tumors are depicted as sharply delineated smooth oval or round homogeneous masses with moderate or high contrast enhancement [15, 32, 33, 35, 36] (Fig. 1). The CT criteria used to describe and categorize GISTs were published by Burkill et al. [33, 37] (Table 5). Most GISTs present as exophytic, well-defined, round or oval lesions [32, 34, 37, 38]. Heterogeneous characteristics due to the presence of necrosis or fluid are commonly seen in larger tumors, compared with smaller tumors which habitually are homogeneous masses [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] (Figs. 2 and 3) (Table 6). Malignant GISTs present with distant metastasis most commonly to the liver or with local invasion of surrounding tissues and organs [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39].

a First portion duodenal GIST showing homogeneous enhancement presenting in a 45-year-old woman. This tumor appeared as a well-defined endophytic, sharply delineated smooth oval round homogeneous mass with moderate contrast enhancement. b The tumor measured 21 mm on diameter. The patient undergone laparoscopic resection, including the first duodenal portion and part of the gastric antrum, with a Roux-en-Y reconstruction

a Second portion duodenal GIST showing heterogeneous strong enhancement in the arterial phase, presenting in a 40-year-old woman. This transversal CT view shows a heterogeneous, highly enhanced and well-defined tumor in the medial wall of the second duodenal portion infiltrating the pancreatic head. The patient was resolved with the Whipple procedure. b Lateral CT view showing the duodenal GIST measuring 4 cm on its lateral dimension. c Coronal view depicting the duodenal GIST measuring 3 cm on its frontal dimension

a Coronal view showing a GIST in the lateral wall of the third duodenal portion, measuring 3 cm on diameter, presenting in a 61-year-old woman. b The tumor was well-defined, homogenous, and highly enhanced with contrast, depicting endophytic and exophytic growth. The patient was treated with a wedge resection leaving a large defect on the duodenal wall; the reconstruction was achieved by a side-to-side Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy

Magnetic Resonance

Magnetic resonance (MRI) is comparable with CT [17, 37]. On MRI, solid GISTs have a low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images [7, 15, 36]. Necrosis and hemorrhage within the tumor can influence the signal intensity of MRI images [17]. The administration of gadolinium enhances the intensity of T2-weighted images [36].

Endosonography

This study, while not widely available, should be used to identify the exact location of the tumor within the duodenal wall and its relationships with adjacent structures, mainly the papilla of Vater and the pancreatic head.

Neoadjuvant Therapy

The first successful small molecule inhibitor was imatinib mesilate, which was initially developed as a specific inhibitor of PDGFR [40]. Posteriorly, it was found to be a potent inhibitor of wild-type KIT and various types of mutated KIT found in GISTs [10, 40, 41]. GIST patients with mutations in exon 11 have the best response, whereas patients without either KIT or PDGFR-α mutations do not have a response to imatinib [40, 41]. Complete responses to imatinib have not been observed in patients with GIST [40]. The first clinical report of successful use of imatinib mesilate in the treatment of a patient was published in 2001 [4], afterwards a rapid development of clinical trials [41] prompted the approbation of imatinib mesilate by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of GIST in 2002 [10]. The indications for neoadjuvant therapy with imatinib are downsizing large GISTs in order to attempt surgery [10, 42] and the treatment of advanced or metastatic tumors [41]. In selected cases of locally advanced or marginally resectable primary GISTs, the strategy of cytoreduction with neoadjuvant imatinib therapy has become a common, established, and approved approach [43,44,45]. The use of neoadjuvant imatinib in routine practice associated to surgery has excellent long-term results, as has been demonstrated by the largest trial on patients with GISTs, of whom 10% had duodenal tumors [43].

Indications for Neoadjuvant Imatinib Therapy

Complete resection of large GISTs is sometimes difficult for technical reasons. In such cases, neoadjuvant therapy with imatinib has been attempted (Table 7) [19, 42, 43, 45]. The candidates for preoperative imatinib treatment are those patients who may benefit from downstaging the tumor before operation; this strategy is especially attractive in difficult locations such as the duodenum, mainly the second and third portion, where resection of the primary tumor may cause significant morbidity or functional deficits [43]. After reducing the size of the tumor, it would be successfully removed in 80% or more cases [42, 43]. In series of duodenal GISTs, imatinib was applied preoperatively with good results in patients affected with large high-risk tumors who will likely undergo a complex procedure such as pancreatoduodenectomy [19, 20]. In these cases besides reducing the tumor size and because primary tumors are fragile and hypervascular, preoperative imatinib therapy may decrease the risk of bleeding, postoperative complications, or tumor fragility and rupture [20, 43].

Dose and Management of Neoadjuvant Imatinib Therapy

The recommended dose of imatinib in the neoadjuvant setting is 400 mg daily until a maximal response is attained and confirmed with two consecutive CT scans not showing further tumor regression or until the surgeon deemed a radical organ sparing resection possible, whichever condition was attained first [42, 43]. The optimal duration of preoperative therapy ranges from 4 to 12 months to achieve a maximal dimensional response to imatinib. This is the time when a plateau in tumor shrinkage is usually seen, and the risk of development of secondary resistance to therapy is still very low. At this time, careful response assessment with CT scans should be undertaken not to miss the timing for surgery [43]. Postoperative imatinib adjuvant therapy should be used routinely in patients considered for neoadjuvant therapy [43].

Surgical Treatment

Complete surgical resection is the only curative treatment for GISTs [10, 17, 24,25,26,27, 43]. Optimal surgical treatment entails complete removal of the tumor with clear surgical margins, including adjacent organs [26]. Due to the absence of lymph node metastasis or infiltrative submucosal growth and because GISTs are well-encapsulated tumors that rarely have a tendency to local invasion, local excision or segmental duodenectomy, if feasible, is sufficient and has been associated to prolonged disease-free survival [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, 25, 26, 28]. Surgical removal of duodenal GISTs may be accomplished by several options ranging from minimal to major procedures [17, 24, 27, 28]. The approach should be dictated by the location of the lesion within the duodenum and the ability to achieve an R0 margin [19, 25]. Conservative surgery constitutes local segmental or wedge resection and while technically feasible must be carefully evaluated due to the complex duodenal anatomy and proximity to crucial structures such as the papilla of Vater, pancreas, mesenteric vessels, common biliary duct, and pancreatic duct [7, 19, 20, 26, 28, 30]. Consequently, local segmental or wedge resections are most times difficult to perform, especially in the second portion [16, 19]. In clinical practice, 20% to 86% of duodenal GISTs have been reported to be treated with pancreatoduodenectomy [26]. Reported surgical options for duodenal GISTs depend on tumor location and size (Table 8) [15,16,17,18,19,20,21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

First Duodenal Portion

Large tumors located on the medial wall of the first duodenal portion in close contact with the pancreatic head should be treated by pancreatoduodenectomy [16, 19, 20, 24, 25, 27, 29, 30], while those GISTs located in the lateral wall, if less than 2 or 3 cm, could be treated by wedge resection with primary closure or segmental resection with primary anastomosis including Billroth I procedure or Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy [17, 24, 25, 27, 30, 46] (Fig. 4).

Surgical procedures for GISTs located in the first duodenal portion (D1). a Wedge resection with primary suture. b Segmental resection with primary anastomosis (including Billroth I procedure). c Duodenal GIST requiring extensive segmental resection. D. Reconstruction of an extensive first duodenal portion segmental resection with a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunal anastomosis

Second Duodenal Portion

The decision to perform a pancreatoduodenectomy in patients with GISTs of the second duodenal portion is influenced by the relationships of the tumor with the pancreatic head and papilla of Vater. Large or small tumors located on the medial wall in close contact with the pancreatic head should be treated by pancreatoduodenectomy [16, 19, 20, 24, 25, 29, 30, 42, 47, 49]. Tumors located on the lateral wall can be submitted to local wedge resection with primary closure of the duodenal wall or distal duodenectomy including the tumor and reconstruction with lateral or terminal anastomosis between the first jejunal loop and the duodenum or Roux-en-Y anastomosis between the duodenum and the jejunum [15, 19, 25, 27, 29, 48] (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, the indication of segmental or wedge resection will be dictated by the size of the tumor and the possibility to achieve R0 resection [27]. Anecdotally, re-implantation of the papilla of Vater in a jejunal patch during segmental resection of the second portion of the duodenum has been described [28]. Whenever the patency of the ampulla of Vater is at risk or when the margin of the resection is very close to this structure, a papilloplasty must be performed in order to secure exocrine outflow through the papilla [50].

Third Duodenal Portion

Small or middle size tumors located on the medial or lateral wall of the third duodenal portion may be treated by resection of the third and fourth duodenal portions and primary end-to-end or side-to-end anastomosis with the jejunum [27, 51, 52] (Fig. 6a and b). In the case of wedge resection, primary closure may be attempted [53]. In the case that primary closure would not be achieved, a Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy could be performed [27] (Fig. 6c and d). Large tumors located on the medial wall and in close contact with the pancreatic head or infiltrating the pancreas should be treated with pancreatoduodenectomy [19]. Tumors located on the lateral wall can be submitted to local wedge resection with primary closure of the duodenal wall or Roux-en-Y anastomosis between the duodenum and the jejunum [15, 19, 27, 29].

Surgical procedures for GISTs located in the third duodenal portion (D3). a Distal duodenectomy including the third and fourth portions. b Reconstruction of distal duodenectomy with end-to-side duodenojejunostomy. c Wedge resection of a third portion duodenal GIST. D. Reconstruction of third portion duodenal GIST resection with a Roux-en-Y duodenojejunostomy

Fourth Duodenal Portion

GISTs located on the fourth duodenal portion may be locally resected and the intestinal transit restored by a primary end-to-end or end-to-side anastomosis between the third duodenal portion and jejunum [17, 23, 27] (Fig. 7). Small tumors could be treated with wedge resection [53].

Laparoscopic Surgery

Laparoscopic surgery has been firmly established in patients with suspected gastric GIST and has been included within formal therapeutic strategies to treat these tumors [54]. However, laparoscopic resection of duodenal GIST has not been established, and anecdotal experiences have been published, including two first duodenal portion GISTs treated by wedge resection and primary closure with excellent disease-free survival [17]. Laparoscopic pancreatoduodenectomy has been successfully described in malignant pancreatic tumors and, consequently, makes sense to use this approach to second portion duodenal tumors with indication of the Whipple resection. Nonetheless, most authors exclude duodenal GISTs from laparoscopic resection [55].

Surgical Controversies

Ultimately, the decision to perform pancreatoduodenectomy for duodenal GISTs depends not only on the localization but also on the tumor size [20, 26]. Duodenal GISTs, which occur mostly in the second duodenal portion, frequently present with a diameter of more than 5 cm; consequently, they are more likely to be submitted to pancreatoduodenectomy [19, 20]. In Table 9, the differences and characteristics of GISTs subjected to pancreatoduodenectomy and local resection are depicted. Another subject of controversy is the necessity to perform lymphadenectomy. Because GISTs do not spread via lymphatic drainage, lymphadenectomy is not routinely performed, and some authors who had performed lymphadenectomy found metastasis in 2% or less [19]. Regarding the necessity of concomitant procedures, they should be performed in order to completely resect the tumor [26, 27]. It has been found that the need of additional procedures is similar in patients subjected to local resection or pancreatoduodenectomy, with a frequency ranging from 4 to 31% [19, 26].

Adjuvant Therapy

Imatinib mesilate is considered the first line of therapy for advanced GIST, improving disease-free survival and overall survival [4, 20, 43]. Imatinib has been approved for adjuvant therapy in patients after resection of primary GISTs with significant risk of recurrence (400 mg daily) [43, 56]. Sunitinib maleate is considered second-line therapy for imatinib-refractory GISTs [10]. Patients with high-risk tumors have a demonstrated benefit on overall survival and disease-free survival by adjuvant treatment with imatinib for 3 years, and this indication is the standard of care in such cases [20].

Imatinib Resistance

Initial resistance to imatinib therapy ranges from 9 to 13% [56]. Imatinib resistance may be primary or secondary according to the period of time from the onset of treatment to development of metastases or local recurrence [56,57,58,59]. Early or primary resistance develops within the first 3 months of treatment in 9% to 15% of all patients; late, acquired, or secondary resistance develops after 24 months of treatment in approximately 44% of all patients [57,58,59]. Some prognostic risk factors to predict the response of GISTs to imatinib have been identified. One of the most important is the mutational status of KIT/PDGFR-α; patients with mutations in exons 11, 13, and 17 have a better response [57, 59]. Other genes predicting a good response are localized in the chromosome 19p corresponding to the KRAB-ZNF91 complex [58]. In patients with primary or secondary resistance, secondary mutations in exons 9, 11, 14, and 17 of c-kit have been identified [57]. Mutations of exons 11 and 13 are related to primary resistance, and mutations of exons 11 and 17 associate to secondary resistance [57, 59, 60]. Patients with metastatic or recurrent GISTs initially responding to imatinib and afterwards developing resistance must undergo early surgical exploration because their chances of complete resection are higher [58,59,60,61,62,63]. The use of increased doses of adjuvant imatinib after the second surgery increases the chance of disease-free survival for at least 24 months, and without imatinib treatment, the disease-free survival rarely surpasses 12 months [60, 61]. Although recommendations for adjuvant therapy have demonstrated benefit with continuous therapy for 3 years [20], probably continuous treatment despite the risk of developing resistance in patients with malignant GIST would prolong the chance of disease-free survival [61]. A second generation of tyrosine kinases inhibitors constituted by sunitinib has demonstrated its utility in imatinib-resistant GISTs, particularly in those tumors with mutations in exons 9, 13, and 14 associated to primary resistance [64, 65]. Eventually, sunitinib develops resistance [66, 67], and in those patients, only an aggressive surgical approach would bring the patient a chance to overcome the disease [66, 68]. Other available imatinib-related medication with activity in imatinib-resistant GISTs is nilotinib, which is also active in sunitinib-resistant tumors [69, 70].

Prognosis

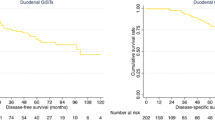

Segmental or wedge resection of duodenal GISTs when feasible has been demonstrated to be sufficient and curative surgical treatment, with satisfactory disease-free survival in series composed specifically of duodenal tumors [24,25,26,27,28]. The prognosis and risk stratification of GIST was defined based on tumor size and mitotic index (Table 4). The survival for a primary tumor larger than 10 cm at 5 years has been estimated to be around 20%, whereas the survival for tumors less than 5 cm could be approximately 47% to 65% [9, 19, 24]. Specifically, patients undergoing resection of localized tumors have an overall survival of 98% at 3 years and 89% at 5 years and disease-free survival of 67% at 3 years and 64% at 5 years [20]. The mitotic index Ki-67 has been linked to prognosis in a large number of studies and should be included in the evaluation of GISTs [16, 17, 24]. Even small GISTs with low mitotic activity may metastasize [10]. However, virtually all GISTs are associated with some risk of recurrence, and approximately 40% to 50% of patients with potentially curative resections develop recurrent or metastatic disease [43]. Another prognostic feature is tumor location, and habitually primary gastric tumors have a better prognosis and are less aggressive than those located in the small bowel or in the rectum [9, 10, 19]. Table 10 depicts various risk factors and predictors for recurrence described in studies of duodenal GISTs. Despite the ample knowledge of the biology of GISTs, these tumors behave somewhat erratically, even among low-risk GISTs recurrences have been reported 20 or more years after surgical resection [9]. In duodenal GISTs, recurrences have been described in 35% to 39% patients [21]. In high-risk tumors, recurrence is inevitable. In patients with a follow-up longer than 2 years, recurrence has been found in 19%, distant metastasis in 13% to 23%, local recurrence in 2% to 15%, and synchronous local and distant recurrence in 4% [19, 21]. The most common site of distant metastasis is the liver [19, 21, 24].

Conclusions

Most articles concerning duodenal GISTs state that unlike tumors involving other sites of the gastrointestinal tract, the optimal surgical procedure for duodenal GISTs has not been well characterized in the literature. That is because clinical randomized trials have not been undertaken and because published reports are mainly the experience of specialized centers. However, when carefully reviewing the published literature on the subject, it was found out that surgical approaches to duodenal GISTs are fairly standard among different authors reporting from different countries and regions of the world. All take in account the localization of GIST within the duodenum and its anatomic relationships to decide whether local resections or pancreatoduodenectomy should be performed. Using this knowledge, defined surgical options for duodenal GISTs according to their localization have been proposed. Besides the controversy regarding the indications for pancreatoduodenectomy, probably the most important issue remaining to be addressed is the implementation of laparoscopic surgery.

References

Joensuu H (2006) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Ann Oncol 17(Suppl. 10):280–286

Mazur MT, Clark HB (1983) Gastric stromal tumors: reappraisal of histogenesis. Am J Surg Pathol 7:507–519

Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, Kawano K, Hanada M, Kurata A, Takeda M, Muhammad Tunio G, Matsuzawa Y, Kanakura Y, Shinomura Y, Kitamura Y (1998) Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science 279:577–580

Joensuu H, Roberts P, Sarlomo-Rikala M et al (2001) Effect of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor STI571 in a patient with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. N Engl J Med 344:1052–1056

Blay JY, Bonvalot S, Casali P, Choi H, Debiec-Richter M, Dei Tos AP, Emile JF, Gronchi A, Hogendoorn PC, Joensuu H, le Cesne A, McClure J, Maurel J, Nupponen N, Ray-Coquard I, Reichardt P, Sciot R, Stroobants S, van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom A, Demetri GD, GIST consensus meeting panelists (2005) Consensus meeting for the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: report of the GIST Consensus Conference of 20–21 March 2004, under the auspices of ESMO. Ann Oncol 16:566–578

Van den Abbeele AD (2008) The lessons of GIST-PET and PET/CT: a new paradigm for imaging. Oncologist 13(Suppl. 2):8–13

Yang F, Jin C, Du Z et al (2013) Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor: clinicopathological characteristics, surgical outcomes, long term survival and predictors for adverse outcomes. Am J Surg 206:360–367

Agaimy A, Wünsch PH (2006) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a regular origin in the muscularis propria, but an extremely diverse gross presentation. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 391:322–329

Corless CL, Fletcher JA, Heinrich MC (2004) Biology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol 22:3813–3825

Kitamura Y (2008) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: past, present, and future. J Gastroenterol 43:499–508

Bórquez PM, Neveu RC (2008) Tumores del estroma gastrointestinal (GIST), un particular tipo de neoplasia. Rev Med Chil 136:921–929

Vij M, Agrawal V, Kumar A, Pandey R (2013) Cytomorphology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a comprehensive morphologic study. J Cytol 30:8–12

Beltrán MA, Vicencio AO, Barra MM, Contreras MA, Wilson CS, Cruces KS (2011) Resultados del tratamiento quirúrgico de los tumores del estroma gastrointestinal (GIST) en la IV Región de Chile. Rev Chil Cir 63:290–296

Beltrán MA, Pujado B, Méndez PE et al (2010) Gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) incidentally found and resected during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg 20:393–396

Uchida H, Sasaki A, Iwaki K, Tominaga M, Yada K, Iwashita Y, Shibata K, Matsumoto T, Ohta M, Kitano S (2005) An extramural gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum mimicking a pancreatic head tumor. J Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat Surg 12:324–327

Huang CC, Yang CY, Lai IR, Chen CN, Lee PH, Lin MT (2009) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the small intestine: a clinicopathologic study of 70 cases in the postimatinib era. World J Surg 33:828–834

Chung JC, Chu CW, Cho GS, Shin EJ, Lim CW, Kim HC, Song OP (2010) Management and outcome of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum. J Gastrointest Surg 14:880–883

Lin C, Chang Y, Zhang Y, Zuo Y, Ren S (2012) Small duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting with acute bleeding misdiagnosed as hemobilia: two case reports. Oncol Lett 4:1069–1071

Johnston FM, Kneuertz PJ, Cameron JL, Sanford D, Fisher S, Turley R, Groeschl R, Hyder O, Kooby DA, Blazer D III, Choti MA, Wolfgang CL, Gamblin TC, Hawkins WG, Maithel SK, Pawlik TM (2012) Presentation and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum: a multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 19:3351–3360

Colombo C, Ronellenfitsch U, Yuxin Z, Rutkowski P, Miceli R, Bylina E, Hohenberger P, Raut CP, Gronchi A (2012) Clinical, pathological and surgical characteristics of duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor and their influence on survival: a multi-center study. Ann Surg Oncol 19:3361–3367

Beham A, Schaefer IM, Cameron S, von Hammerstein K, Füzesi L, Ramadori G, Ghadimi MB (2013) Duodenal GIST: a single center experience. Int J Color Dis 28:581–590

Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C et al (2002) Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol 33:459–465

Beltrán MA, Barría C, Contreras MA, Wilson CS, Cruces KS (2009) Tumor del estroma gastrointestinal (GIST) en una paciente con neurofibromatosis tipo 1. Rev Med Chil 137:1197–1200

Wu TJ, Lee LY, Yeh CN, Wu PY, Chao TC, Hwang TL, Jan YY, Chen MF (2006) Surgical treatment and prognostic analysis for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) of the small intestine: before the era of imatinib mesylate. BMC Gastroenterol 6:29

Buchs NC, Bucher P, Gervaz P, Ostermann S, Pugin F, Morel P (2010) Segmental duodenectomy for gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum. World J Gastroenterology 16:2788–2792

Tien YW, Lee CY, Huang CC, Hu RH, Lee PH (2010) Surgery for gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the duodenum. Ann Surg Oncol 17:109–114

El-Gendi A, El-Gendi S, El-Gendi M (2012) Feasibility and oncological outcomes of limited duodenal resection in patients with primary nonmetastatic duodenal GIST. J Gastrointest Surg 16:2197–2202

Bourgouin S, Hornez E, Guiramand J, Barbier L, Delpero JR, le Treut YP, Moutardier V (2013) Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): arguments for conservative surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 17:482–487

Relles D, Baek J, Witkiewicz A, Yeo CJ (2010) Periampullary and duodenal neoplasms in neurofibromatosis type 1: two cases and an updated 20-year review of the literature yielding 76 cases. J Gastrointest Surg 14:1052–1061

Agaimy A, Vassos N, Croner RS (2012) Gastrointestinal manifestations of neurofibromatosis type 1 (Recklinghausen’s disease): clinicopathological spectrum with pathogenetic considerations. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 5:852–862

Beltrán MA, Cruces KS, Barría C, Verdugo G (2006) Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the ileum and neurofibromatosis type 1. J Gastrointest Surg 10:297–301

Lee CM, Chen HC, Leung TK, Chen YY (2004) Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: computed tomographic features. World J Gastroenterology 10:2417–2418

Burkill GJ, Badran M, Al-Muderis O et al (2003) Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: distribution, imaging features, and pattern of metastatic spread. Radiology 226:527–532

Kim JY, Lee JM, Kim KW, Park HS, Choi JY, Kim SH, Kim MA, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI (2009) Ectopic pancreas: CT findings with emphasis on differentiation from small gastrointestinal stromal tumor and leiomyoma. Radiology 252:92–100

Lupescu IG, Grasu M, Boros M et al (2007) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: retrospective analysis of the computer-tomographic aspects. J Gastrointest Liver Dis 16:147–151

Chourmouzi D, Sinakos E, Papalavrentios L, Akriviadis E, Drevelegas A (2009) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a pictorial review. J Gastrointest Liver Dis 18:379–383

Hersh MR, Choi J, Garrett C, Clark R (2005) Imaging gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Control 12:111–115

Buckley JA, Fishman EK (1998) CT evaluation of small bowel neoplasms: Spectrum of disease. RadioGraphics 18:379–392

Ulusan S, Koc Z, Kayaselcuk F (2008) Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: CT findings. Br J Radiol 81:518–623

Krause DS, van Etten RA (2005) Tyrosine kinases as targets for cancer therapy. N Engl J Med 353:172–187

Demetri GD, von Mehren M, Blanke CD, van den Abbeele AD, Eisenberg B, Roberts PJ, Heinrich MC, Tuveson DA, Singer S, Janicek M, Fletcher JA, Silverman SG, Silberman SL, Capdeville R, Kiese B, Peng B, Dimitrijevic S, Druker BJ, Corless C, Fletcher CDM, Joensuu H (2002) Efficacy and safety of imatinib mesilate in advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors. N Engl J Med 347:472–480

Ludvigsen L, Toxvaerd A, Mahdi B, Krarup-Hansen A, Bergenfeldt M (2007) Successful resection of an advanced duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor after down-staging with imatinib: report of a case. Surg Today 37:1105–1109

Rutkowski P, Gronchi A, Hohenberger P, Bonvalot S, Schöffski P, Bauer S, Fumagalli E, Nyckowski P, Nguyen BP, Kerst JM, Fiore M, Bylina E, Hoiczyk M, Cats A, Casali PG, le Cesne A, Treckmann J, Stoeckle E, de Wilt JHW, Sleijfer S, Tielen R, van der Graaf W, Verhoef C, van Coevorden F (2013) Neoadjuvant imatinib in locally advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): the EORTC STBSG experience. Ann Surg Oncol 20:2937–2943

NCCN (2012) Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Soft tissue sarcoma Version 2.2012

The ESMO/European Sarcoma Network Working Group (2012) Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 23(Suppl. 7):vii 49–vii 55

Yildirgan MI, BaşoğM ASS, Albayrak Y, Gürsan N, Önbaş Ö (2007) Duodenal stromal tumor: report of a case. Surg Today 37:426–429

Sakakima Y, Inoue S, Fujii T, Hatsuno T, Takeda S, Kaneko T, Nagasaka T, Nakao A (2004) Emergency pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy followed by second-stage pancreatojejunostomy for a gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum with intramural gas figure: report of a case. Surg Today 34:701–705

Asakama M, Sakamoto Y, Kajiwara T et al (2008) Simple segmental resection of the second portion of the duodenum for the treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg 393:605–609

Morcos B, Al-Ahmad F (2011) A large gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum: report of a case. J Med Case Rep 5:457

Sakamoto Y, Yamamoto J, Takahashi H, Kokudo N, Yamaguchi T, Muto T, Makuuchi M (2003) Segmental resection of the third portion of the duodenum for a gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol 33:364–366

Mennigen R, Wolters HH, Schulte B, Pelster FW (2008) Segmental resection of the duodenum for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). World J Surg Oncol 6:105

Ghidirim G, Mishin I, Gagauz I, Vozian M, Cernii A, Cernat M (2011) Duodenal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Romanian J Morphol Embryol 52(3 Suppl):1121–1125

Shaw A, Jeffery J, Dias L, Nazir S (2013) Duodenal wedge resection for large gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) presenting with life-threatening hemorrhage. Case Reports Gastrointest Med 2013:562642

Sasaki A, Koeda K, Obuchi T, Nakajima J, Nishizuka S, Terashima M, Wakabayashi G (2010) Tailored laparoscopic resection for suspected gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Surgery 147:516–520

Chen YH, Lu KH, Yeh CN et al (2012) Laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal tumors: safe, efficient, and comparable oncologic outcomes. J Laparoendosc Adv Srug Tech 22:758–763

Bickenbach K, Wilcox R, Veerapong J, Kindler HL, Posner MC, Noffsinger A, Roggin KK (2007) A review of resistance patterns and phenotypic changes in gastrointestinal stromal tumors following imatinib mesylate therapy. J Gastrointest Surg 11:758–766

Wang CM, Huang K, Zhou Y, du CY, Ye YW, Fu H, Zhou XY, Shi YQ (2010) Molecular mechanisms of secondary imatinib resistance in patients with gastrointestinal tumors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 136:1065–1071

Rink L, Skorobogatko Y, Kossenkov AV, Belinsky MG, Pajak T, Heinrich MC, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Ochs MF, Eisenberg B, Godwin AK (2009) Gene expression signatures and response to imatinib mesilate in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Mol Cancer Ther 8:2172–2182

Gounder MM, Maki RG (2011) Molecular basis for primary and secondary tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 67:25–43

Yeh CN, Chen TW, Tseng JH, Liu YY, Wang SY, Tsai CY, Chiang KC, Hwang TL, Jan YY, Chen MF (2010) Surgical management in metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) patients after imatinib mesilate treatment. J Surg Oncol 102:599–603

Andtbacka RH, Ng CS, Scaife CL, Cormier JN, Hunt KK, Pisters PW, Pollock RE, Benjamin RS, Burgess MA, Chen LL, Trent J, Patel SR, Raymond K, Feig BW (2007) Surgical resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after treatment with imatinib. Ann Surg Oncol 14:14–24

D’Amato G, Steinert DM, McAuliffe JC, Trent JC (2005) Update on the biology and therapy of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Control 12:44–55

Jiang WZ, Guan GX, Lu HS, Yang YH, Kang DY, Huang HG (2011) Adjuvant imatinib treatment after R0 resection for patients with high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a median follow-up of 44 months. J Surg Oncol 104:760–764

Blay JY (2010) Pharmacological treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an update on the role of sunitinib. Ann Oncol 21:208–215

Younus J, Verma S, Franek J, Coakley N (2010) Sunitinib maleate for gastrointestinal stromal tumor imatinib mesylate-resistant patients: recommendations and evidence. Current Oncol 17:4–10

Kikuchi H, Setoguchi T, Miyazaki S, Yamamoto M, Ohta M, Kamiya K, Sakaguchi T, Konno H (2011) Surgical intervention for imatinib and sunitinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Int J Clin Oncol 16:741–745

Wang WL, Conley A, Reynoso D, Nolden L, Lazar AJ, George S, Trent JC (2011) Mechanisms of resistance to imatinib and sunitinib gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 67:15–24

Dudeja V, Armstrong LH, Gupta P, Ansel H, Askari S, Al-Refaie WB (2010) Emergence of imatinib resistance associated with downregulation of c-kit expression in recurrent gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): optimal timing of resection. J Gastrointest Surg 14:557–561

Montemurro M, Bauer S (2011) Treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumor after imatinib and sunitinib. Curr Opin Oncol 23:367–372

Sawaki A, Nishida T, Doi T, Yamada Y, Komatsu Y, Kanda T, Kakeji Y, Onozawa Y, Yamasaki M, Ohtsu A (2011) Phase 2 study of nilotinib as third-line therapy for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Cancer 117:4633–4641

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beltrán, M.A. Current Management of Duodenal Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Indian J Surg 82, 1193–1205 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-020-02210-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-020-02210-1