Abstract

Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus often, is asymptomatic in the immunocompetent but can cause life threatening infection in immunocompromised patients. It is uncommon in the solid organ transplant recipients with an incidence of < 1%, majority occurring within 2 years of transplantation. It can be either endogenous reactivation of latent infection, de novo acquisition, or donor-derived infection. Disseminated infection is common, with non-specific symptoms, fever being the commonest. None of the available tests is 100% accurate. Modification of immunosuppression and anti-fungal can achieve 90% success rate. We report a liver transplant recipient, 3 months post-transplantation on everolimus, prednisolone, mycophenolate, and tacrolimus who had isolated hepatic histoplasmosis and responded to treatment. Liver biopsy revealed epithelioid granulomas with narrow-based budding yeast, suggesting histoplasma. Contrast CT abdomen revealed normal attenuation of graft liver few small non-enhancing hypodense lesions seen scattered in both lobes. And this patient was managed with just reduction of immunosuppressive doses as the patient was having renal dysfunction; starting itraconazole will lead to further deterioration in the clinical course and also interact with calcineurin inhibitors and mycophenolate mofetil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Liver involvement as a part of disseminated histoplasmosis which usually originates in the lung is well known. However, extrapulmonary hepatic histoplasmosis as a primary manifestation is extremely rare. The increasing use of immunosuppressive medications, such as tumor necrosis factor and calcineurin inhibitors, has resulted in rising incidence of the fungal infection, which is particularly relevant to the transplant population [1]. Infection usually involves inhaling an inoculum of Histoplasma capsulatum and with the inactivation of T lymphocytes by calcineurin inhibitors; macrophages are not initiated to inhibit the growth of the fungal infection, leading to increased fungal burden and mortality [2]. Here we describe a case of histoplasmosis in a liver transplant recipient 3 months after transplantation, with histopathology illustrating the yeast-like fungal elements.

Case Report

The patient is a 48-year-old man who, in November 2018, underwent a deceased donor liver transplantation for chronic liver disease (hepatitis B related). Postoperatively, ultrasound showed a normal liver transplant allograft with excellent perfusion. He had been doing well since transplant until 3 months when he had elevated transaminases, i.e., SGOT 132 U/L (reference range 5–40 U/L) and SGPT 324 U/L (reference range 5–40 U/L), on mycophenolate, everolimus, prednisolone, tacrolimus, entecavir, and valganciclovir.

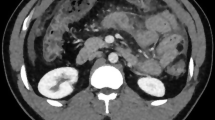

His elevated transaminases persisted (Table 1) all through his follow-up, up to the maximum of SGOT-399 U/L and SGPT-599 U/L (January 2019). Later, the patient also developed itching, malaise, and loss of appetite. Abdominal ultrasound revealed hypodense lesions in both lobes of the allograft liver largest measuring 1.5 × 1.5 cm. Contrast CT abdomen revealed normal attenuation of graft liver with few small non-enhancing hypodense lesions seen scattered in both lobes, largest measuring 17 × 16 mm in segment 2. HBsAg was positive, IgM CMV DNA was negative, and anti-HAV total was reactive.

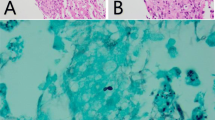

A liver biopsy revealed large areas of hepatocytic loss due to necrotising granulomatous inflammation associated with multinucleated giant cells and adjacent dense chronic inflammation (Fig. 1). Gomori methenamine silver stain revealed silver positive intracellular yeast-like elements with narrow-based budding favoring Histoplasma (Fig. 1). No portal-based features of acute rejection were noted and bile ducts were preserved in the majority of portal tracts.

As we know that itraconazole is the drug of choice, still, he was not started on any anti-fungal therapy in view of suspected renal dysfunction (creatinine 1.2 mg/dL) and increased chance of itraconazole interacting with calcineurin inhibitors and mycophenolate mofetil. Rather, his immunosuppression regimen was decreased and mycophenolate was withdrawn temporarily. With surveillance CECT abdomen (June and October 2019), the lesions in graft liver disappeared, graft was uniform with normal echotexture, and his liver function tests returned to normal.

Discussion

Once the pathogen disseminates extracellularly through blood or lymph, it becomes a progressive disseminated histoplasmosis with symptoms that reflect diverse end organ effects [3]. More than two-third of cases described are within the first 2 years of transplantation [1]. This case, contracted 3 months later, serves as the first to our knowledge that illustrates granulomas and intracytoplasmic yeast-like fungi within the liver parenchyma of the transplant allograft.

Suspicious lesions in donors should be examined by histopathology and fungal culture. If granuloma were observed, serum and urine should be tested for Histoplasma antigen and serum should be tested for anti-Histoplasma antibodies [4].

In a case report [5] after 10 years of transplant (for glycogen storage disease), liver biopsy revealed to have lobular epithelioid granulomas with intracellular yeast-like elements. The patient had progressive disseminated histoplasmosis manifested as granulomatous hepatitis. He completed a course of liposomal amphotericin B and continued itraconazole therapy for a year. His immunosuppression regimen was significantly decreased and mycophenolate was stopped. The follow-up liver biopsy revealed significantly decreased microgranulomas and yeast elements.

In another case report [6], a 44-year-old man with end-stage liver disease (hepatitis C related) underwent a cadaveric liver transplantation. Six months he was admitted with hypotension, fever, and acute renal failure (serum creatinine level, 7.9 mg/dL). The fever continued with respiratory difficulty, worsening infiltrates on chest radiographs, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and no response to Ganciclovir or amphotericin B. A bone marrow biopsy specimen contained granulomas, consistent with Histoplasma. Response to amphotericin B was dramatic, and the patient was started on oral anti-fungal prophylaxis of itraconazole (400 mg/day).

Conclusion

Because of the non-specific symptoms and because its time to onset varies, continued clinical suspicion for and vigorous diagnostic pursuit of histoplasmosis result in its timely diagnosis and treatment. Histoplasma polysaccharide antigen testing of serum and urine, which may be done rapidly, offers a sensitivity of 90% in disseminated disease [7]. Blood cultures have a sensitivity of approximately 85% but may take several days to weeks before identifiable organisms will grow [8]. Although disseminated disease is common among the prognosis appears to be good. In our patient, it was a close call to decide whether to go with reducing the immunosuppressants and or to start anti-fungal.

References

Assi M, Martin S, Wheat LJ et al (2013) Histoplasmosis after solid organ transplant. Clin Infect Dis 57:1542–1549

Kauffman CA (2007) Histoplasmosis: a clinical and laboratory update. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:115–132

Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Avery RK, Lard M et al (2009) Histoplasmosis in solid organ transplant recipients: 10 years of experience at a large transplant center in an endemic area. Clin Infect Dis 49:710–716

Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, Baddley JW, McKinsey D, Loyd JE, Kauffman CA, Infectious Diseases Society of America (2007) Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 45:807–825

Washburn L, Galván NT, Dhingra S, Rana A, Goss JA (2017) Histoplasmosis hepatitis after orthotopic liver transplantation. J Surg Case Rep 2017(12):rjx232 Published online 2017 Dec 11

Shallot J, Pursell KJ, Bartolone C, Williamson P, Benedetti E, Layden TJ, Wiley TE (1997) Disseminated histoplasmosis after orthotopic liver transplantation, liver transplantation and surgery. 3(4):433–434

Wheat LJ, Kohler RB, Tewari RP (1986) Diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis by detection of Histoplasma capsulatum antigen in serum and urine specimens. N Engl J Med 314:83–88

Kaufman L (1992) Laboratory methods for the diagnosis and confirmation of systemic mycosis. Clin Infect Dis 14(supp 1):23–29

Acknowledgements

The research was performed at the Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and Liver Transplant, Global Hospitals, Hyderabad.

Contribution Details

All authors contributed almost equally in preparing this case report starting from concept, design, data collection, literature search, to manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maharaj, R., Kapoor, D., Dekate, J. et al. Histoplasmosis After Liver Transplantation—a Skate on Thin Ice if Left Undiagnosed. Indian J Surg 82, 695–697 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-019-02048-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-019-02048-2