Abstract

This is an empirical investigation into life satisfaction, using nationally representative German panel data. The study confirms with modern econometric techniques the previously found substantial association with an individual’s thoughts about the future, whether they are optimistic or pessimistic about it, with life satisfaction. In addition, the investigation demonstrates that the association holds when some possibly anticipated events (like, for example, divorce and unemployment) are controlled for. Furthermore, including individuals’ optimism and pessimism about the future substantially increases the explanatory power of standard life satisfaction models. The effect size is greater for individuals who report being pessimistic than that for well-understood negative events like unemployment. These effects are attenuated though do remain substantial after controlling for the following: individual fixed effects; statistically matching on observable variables between optimistic and pessimistic individuals; and addressing the potential endogeneity of optimism and pessimism to life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Within the economics discipline, many investigations into well-being focus on objective factors (income, labour force status, marital status, education, health) and, in many cases, have convincingly demonstrated associations and causal connections. Investigations considering subjective factors are rarer, although, as studies from economics and more frequently from the wider social sciences in general show, these factors are also very important for individual well-being and life satisfaction. The well-known study of Winkelmann and Winkelmann (1998), for example, demonstrated that much of the loss of life satisfaction from entering unemployment was non-pecuniary, and some of these non-pecuniary factors were subjective (for example self-esteem, feelings of loneliness and a lack of purpose). For other studies of subjective factors and well-being see Baumeister et al. (2003) and Ho et al. (2010). The meaning of happiness itself may be subject to different subjective feelings. Over the lifecycle, Mogilner et al. (2011) find differing meanings for happiness, notably excitement for young people, and a sense of peace for the not so young. In short, the inclusion of, or controlling for, subjective states and factors may even enhance collective understanding of how objective factors are related to well-being.

This study is an investigation of a subjective factor: the association of what individuals think about the future—whether they are optimistic or pessimistic—and their life satisfaction now. Using nationally representative German panel data, evidence is presented that people who are pessimistic about the future, compared with people who are quite optimistic, are much less satisfied with life. Conversely, there is a life satisfaction premium associated with feeling optimistic about the future compared to being merely quite optimistic. Clearly, the thoughts that an individual has about the future are important for current life satisfaction; moreover, including a measure of an individual’s thoughts about the future substantially increases the explanatory power of well-being models.

This empirical investigation uses four methods to establish this result: ordinary least squares (OLS); fixed effects (FE); System General Method of Moments; and FE following the entropy balancing procedure. All four methods point to the same result: a substantial relationship between what individuals think about the future and their satisfaction with their life. In finding this result, this investigation confirms and extends previous similar findings. For example, Becchetti et al. (2013) investigate life satisfaction via eleven sub-components and find that answers to the question “How often do you look forward to another day?” are an important contributor to an understanding of well-being. Senik (2008) uses Russian Panel data to link life satisfaction to an individual’s expectations about whether they and their family will live better in the next twelve months. These results suggest that individuals’ thoughts about the future should be more widely considered in well-being investigations than they are now; the resulting increase in explanatory power over “standard” well-being equations can approach 40%. Such thoughts are important determinants of current well-being and, in terms of size, of larger effect than unemployment which, as many studies show (including this one), is a major negative influence on well-being.

Other research within economics has acknowledged the possibility that the thoughts and feelings an individual has about the future may have an impact on current well-being. Haucap and Heimeshoff (2014) investigate the causal effect of studying economics on well-being and find that perceived good future job prospects (which they suggest could also be a proxy for future income) are positively associated with student life satisfaction scores. Frijters et al. (2012) use a Chinese household cross section survey and show evidence that optimistic expectations are among the most important explanatory variables for general happiness. Using a wave of the SOEP, Grözinger and Matiaske (2004) investigate, in part, the impact of regional unemployment on overall life satisfaction. They argue that the greater regional unemployment is, the greater the fear about future unemployment, and thus the lower individual life satisfaction is. One study links the future and the present via climate change, with expectations about climate change demonstrated to have an impact on current well-being. The authors, Osberghaus and Kühling (2016), provide robust evidence that worsening expectations about future climate change negatively affect well-being, though the size of the effect is not large.

A literature review about optimism provides a summary of the main findings from psychology, making positive links with it and subjective well-being, better health and business and career success while demonstrating that optimism is a nuanced concept (Forgeard and Seligman 2012). Similarly, Kleiman et al. (2017) link optimism, in part, to overconfidence and a sense of invulnerability. Generally, optimism seems to have been studied more than pessimism. A simple Google Scholar search supports this claim, with optimism resulting in over three times as many hits as pessimism. This might be slightly unfortunate: the results below suggest a greater impact on individual well-being of pessimism than optimism.Footnote 1 A recent study using the same data that this study uses finds that pessimism may better promote future physical health outcomes which may, in turn, promote well-being then, if not current well-being (Lang et al. 2013).

Rather than discuss the concepts of optimism and pessimism, this empirical investigation uses many waves of a nationally representative panel dataset to investigate the association of life satisfaction with whether individuals are optimistic or pessimistic about the future. As a largely empirical study, the contribution to knowledge comes in the form of more empirical evidence, using more sophisticated methods than previously used to investigate optimism and pessimism. In addition, given the data and the sophistication of the methods used, it has also been possible to control for some future changes in an individual’s life that they may be expecting and thus may influence current optimism and pessimism.

In summary, this investigation takes advantage of the longitudinal nature of the data, and the rich socio-economic information it contains, and employs different estimation techniques each with advantages. These advantages are discussed more in the next two sections, but as a brief summary the estimates control for some potentially important factors (all methods), account for individual unobserved heterogeneity (all methods apart from OLS), account for the potential endogeneity of optimism and pessimism with life satisfaction (System General Method of Moments), and employ a statistical procedure to generate substantial overlap between the optimistic and pessimistic with respect to observable control values (entropy balancing). The rest of this empirical investigation is organised as follows: Sect. 2 describes the data and methods used; the results are presented in two subsections within Sect. 3, which also discusses a variety of robustness tests; a discussion of the results and their implications is found in Sect. 4, which includes limitations of the investigation and suggestions for future research; and Sect. 5 concludes.

2 Data description, sample, and methods used

The dataset employed here is the SOEP, a well-established longitudinal dataset containing much socio-economic information from a large and representative sample of Germans over the past thirty years. Used for many different investigations within economics and other social sciences, detailed information regarding the dataset can be found in Goebel et al. (2019). The main question used in this investigation asks about the ‘future in general’ and individuals can choose whether they are optimistic, more optimistic than pessimistic, more pessimistic than optimistic, or pessimistic. This question was asked in the following years: 1990–1993; 1995–1997; 1999; 2005; and 2008–2009.Footnote 2 In most of the equations estimated, the responses have been turned into dummy variables and added to a standard well-being equation. Approximately 8% of the sample rate themselves as optimistic, half of the sample report themselves as being more optimistic than pessimistic, a quarter more pessimistic than optimistic with the remaining 5% stating that they are pessimistic. Well-being itself is captured by a question which asks individuals to rate how satisfied they are with life on an 11-point Likert scale. Reviews of economic well-being studies which make use of such scales can be found in Clark et al. (2008a), Stutzer and Frey (2012), and Clark (2018). Table 5 shows the distribution of the optimism and pessimism categories, according to life satisfaction, and Table 6 shows differences for socio-economic variables according to the level of optimism.

Although many of the variables are well-known, and somewhat self-explanatory, the labour force status variables need some explanation. The ‘conventionally’ employed are split into two categories: employed and government employed. This is because of the greater security that German government employees possess, for example in terms of job security, regarding their pensions and also private health insurance, which is more than most other employees.Footnote 3 It is perhaps likely that these additional benefits will make government employees systematically less pessimistic about the future than other employees. Unemployed refers to individuals who are in the labour market but cannot find work, in contrast to individuals not in the labour market (a house husband, for example). Table 6 reveals some substantial differences between individuals who are in differing optimistic and pessimistic categories. Most notably, there is a difference in excess of 2 points (on the 11-point scale) for life satisfaction between those who are optimistic and pessimistic; individuals who are quite optimistic and quite pessimistic (and not fully) are also reasonably far apart (being about 0.8 different). These are large differences, larger than those normally found in investigations of objective data.

An important part of the research strategy is that the standard correlates from the literature are used as control variables: hence the investigation is asking what, if we take into account marital status, labour force status (etc.), is the impact of an individual’s thoughts about the future on their life satisfaction. These control variables are important. It is well-known that unemployed people are less satisfied with life, for example, and the SOEP data show that, in this sample on average, they feel more pessimistic about the future than the employed. Thus, not controlling for unemployment may mean that the results reflect the lower life satisfaction of the unemployed and not pessimistic thoughts about the future itself. A differing impact by income is also possible, and hence, income is also used as a control variable. Similar reasoning applies to the other control variables like health.Footnote 4 Thus, to test the impact of such variables which might affect both optimism (and pessimism) and life satisfaction directly independently, a first estimation is undertaken in which life satisfaction is regressed on the set of optimism and pessimism dummy variables and the perhaps exogenous variables of gender (though, of course, not in the FE contexts) age group and wave dummy variables. The results of this informal test demonstrate that the potential confounders do reduce the strength of the association between optimism (and pessimism) and life satisfaction which, however, still remains substantial when the standard controls are taken into account.

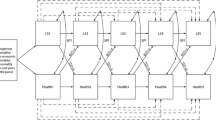

The estimations are undertaken with four different methods: OLS; FE; and FE following entropy balancing, and System GMM.Footnote 5 For comparability, the same sample is used in each case. In practice, this means that the person-year observations used in the System GMM estimation (which is more demanding in terms of its data needs and, hence, has the smallest sample) are also used for OLS and both types of FE estimation. In the particular sample generating the main results the size is 40,590 and the mean number of observations per individual is 3.05 (3.14. for men and for women 2.94). These results are, however, robust to relaxing this restriction.

3 Results from OLS and FE estimations

This discussion of the results first includes those from OLS, then FE, and finally FE following the entropy balancing procedure, with the results from the System GMM analysis presented in Appendix 2. As discussion proceeds from one model’s results to the next, supporting methodological comments are made. As mentioned in the previous section, for all models, the same person-year observations are employed for reasons of consistency and (to some extent) comparability.Footnote 6 For all the estimates apart from the one(s) following the entropy balancing procedure, the base category, against which the results for the dummy variables for being optimistic, quite pessimistic, and pessimistic are to be compared, is quite optimistic. Thus in Table 1, for both genders combined with standard controls (the second column of coefficients), the individuals who are optimistic about the future are, on average, 0.4 more satisfied (on the positively coded 0 to 10 scale) with their life than people who are quite optimistic. Individuals who are quite pessimistic or pessimistic are 0.6 and 1.3 less satisfied with life, respectively. These are substantial values: their size demonstrates a comparable or greater association with life satisfaction than most of the control variables, which are generally considered important confounders in well-being investigations (and hence are necessary to include). These results also include time (all columns) and region (columns 2–4) dummies to control for otherwise unobserved influences specific to a particular year or to a particular region.Footnote 7

Regarding the variables employed as control variables typical of those in the literature, the coefficients in Table 1 are, on the whole, unsurprising: they have the expected sign and are similar to those generally reported in the literature (see the reviews mentioned above). The inclusion of the perception of the future dummy variables increases considerably the explained variation of life satisfaction. Compared to the same estimation without these variables, there is an increase in the R2 of 6 percentage points (representing 30% of the originally explained variation). This figure is for the whole sample (with the full set of controls), but is similar to those for each of the individual genders.

While these pooled OLS results show that optimism and pessimism are significantly associated with current life satisfaction, there are some concerns. One of these is that the respondent may have been interviewed on a particularly good (or bad) day, eliciting a good (or bad) mood that may have resulted in particularly high optimism (pessimism) for the future as well as particularly high (low) current life satisfaction. To somewhat address this issue of mood, these pooled OLS regressions were estimated again, this time with additional lagged optimism and pessimism values. These lagged variables would pick up the trait of optimism and pessimism but not be subject to the common mood effect mentioned just above. The coefficients obtained for both sets of optimism and pessimism variables are shown in Table 2, are in general smaller than those of Table 1, particularly for males, and all are associated with life satisfaction in the expected ways. The trait of optimism (pessimism) is related positively (negatively) to current life satisfaction. Other concerns, such as someone’s way of responding to surveys (i.e. their response style), are arguably taken care of with analyses taking into account individual fixed effects.

However, pooled cross section OLS results cannot account for individual unobserved heterogeneity, which includes individuals’ personalities, dispositions and response styles. Plausibly, factors including an individual’s personality and disposition can have an impact on the relationship between an individual’s perception of the future and their satisfaction with life. Thus, cross-sectional results should be treated cautiously. Addressing this, the estimates that comprise Table 3 exploit the panel nature of the SOEP, and control for an individual’s personality and disposition with the important caveat that this requires each individual’s personality and disposition to be fixed or slowly moving.Footnote 8 As shown in Table 3, the fixed effects results for optimism and pessimism are similar to those obtained by pooled OLS, though the coefficients are smaller.

Controlling for individual fixed effects (which include personality, disposition, and other time-invariant and slowly moving individual effects), and relying just on ‘within’ variation for estimation, the coefficients have approximately halved. The coefficients are also smaller for other variables like health and unemployment. Thus, the results displayed in Table 3 are qualitatively supportive of those found via OLS.Footnote 9 An individual when optimistic reports higher life satisfaction than the same individual when she is pessimistic. In both cases (OLS and FE), the variation of explained life satisfaction increases when these variables are included in the analysis. This informs us of two things: what people think about the future is important for current well-being; and, as a corollary, the inclusion of hopes and fears helps well-being regressions to explain more of what makes up individual well-being. Analysis employing System GMM also supports this assertion (see Appendix 2).

Going further than just including control variables in the estimation, it is possible to match the optimistic and non-optimistic with respect to the control variables. Matching occurs based on a ‘treatment’ group, and this necessitates a change in the optimism and pessimism variables. The ‘treatment’ group for these estimates is the optimistic (individuals who rate themselves as optimistic or quite optimistic) with the ‘control’ group being pessimistic (quite pessimistic or pessimistic).Footnote 10 The entropy balancing procedure (see Hainmueller 2012) was undertaken to match the first three moments of the control variables, which means that the ‘control’ group, the non-optimistic, have the same mean, variance and skewness as the ‘treated’ group, the optimistic. That is, from a statistical point of view, the distributions of the control variables of treated and control observations largely overlap. The entropy balancing procedure was undertaken for the controls as they were at period t-1; fixed effects analysis following the procedure enables this comparison.Footnote 11 To operationalise this, a dummy variable was created indicating whether someone was optimistic or quite optimistic (1) or not (0), and the obtained coefficients for this dummy variable are of the most interest. The results are shown in Table 4 and indicate that, even if the optimistic and the non-optimistic are made to be the same for one lag of a set of controls (mean, variance and skewness), and the contemporaneous controls are included in the equation estimated, the optimistic are substantially more satisfied with life than the non-optimistic.Footnote 12

The results in the first three tables come from a restricted sample to enable consistency between the three methods. Relaxing this restriction so that the full SOEP sample can be used supports the results above. Optimism and pessimism still have their statistically significant associations with life satisfaction.Footnote 13

Additional estimations were undertaken holding constant future changes in circumstances. This recognises the possibility that, to some extent, pessimism or optimism might reflect current events and changes today that may be expected to give rise to future changes but are not captured by the control variables. For example, an individual’s partner may be very ill and this is likely to be a cause of pessimism about the future. Or an employed individual’s job situation is giving them cause for concern about the future. With longitudinal data, it is easy to identify and control for individuals who will become unemployed, or widowed, in the next year; similarly, it is easy to control for individuals who will become married within the next year (a potential source of optimism) or divorced within the next year (a potential source of optimism or pessimism). By holding these future changes in circumstances constant, i.e. by respecifying our models to include leading values of the respective variables, the obtained coefficients on the optimism and pessimism dummy variables of interest provide details of the association of residual optimism and pessimism with current life satisfaction, i.e. after considering such foreseeable future circumstances. Some of these lead variables are significantly associated with life satisfaction (unemploymentFootnote 14 and marriage) and some are not (divorce and widowhood). However, their inclusion does not change the sign or significance of the optimism and pessimism variables and, in each case, the size of the coefficients is remarkably similar to the estimates without them.Footnote 15 The next section briefly discusses all of these results, and provides some limitations and suggestions for future research.

4 Discussion of results, limitations and suggestions for future research

What individuals think about their future appears to have a strong association with their current life satisfaction, even when accounting for unobserved individual heterogeneity, the likely endogeneity of such thoughts to life satisfaction, and some foreseeable future developments in individuals’ lives. Thoughts are important, and their direction is as expected: individuals who are optimistic about the future enjoy more life satisfaction now, whereas individuals who are pessimistic about the future have, on average, lower life satisfaction now. This was demonstrated with unconditional descriptive statistics as well as by successively more conditional regression analysis.

The impact of pessimism (when measured in terms of life satisfaction, and as estimated by OLS, FE, entropy balanced FE, and dynamic System GMM) is greater than that of optimism.Footnote 16 This is reminiscent of loss aversion, whereby individuals are affected by losses to a greater degree than they are by gains, a phenomenon that has received support in a well-being context (Boyce et al. 2013b; De Neve et al. 2018).Footnote 17 This latter study employs three different datasets and finds, overall, an asymmetric effect on life satisfaction between recessions and periods of economic growth consistent with loss aversion.Footnote 18 Because of this, the authors argue for policy responses that are not just concerned with growth itself, but also with how that growth occurs; with smooth business cycles being preferred to more volatile ones. Furthermore, long periods of smooth growth may, somewhat, help lower individuals’ pessimism and increase optimism and thus be beneficial to their life satisfaction.

Potential policy conclusions stem from this, some of which may be difficult to undertake. Given the importance of individuals’ thoughts about the future, policymakers could try to create credible reasons for optimism. Encouraging awareness and education about the links between optimism and life satisfaction may help some people try to be more positive about the future and therefore increase their current well-being. De Neve et al. (2018) argue for policy responses that are not just concerned with growth itself, but also with how that growth occurs. Furthermore, long periods of stable growth may, somewhat, help lower individuals’ pessimism and increase optimism and thus be beneficial to their life satisfaction.

This research, with its demonstration of the importance of an individual’s thoughts for life satisfaction, indicates that individuals should “guard their thoughts” and do their best to not get trapped into too much negative thinking. This is an aim of cognitive behavioural therapy, and something that Layard, has argued should receive more public resources along with greater funding for, and increased appreciation of, mental health. In Sect. 3 of Layard (2013, p. 6), he explicitly argues for policymakers to make more use of evidence-based methods of psychological therapy, with the most researched being “cognitive behavioural therapy (or CBT), which helps people to reorder their thoughts and thus manage their feelings and behaviour”. A further economic argument for increased resources for mental health has been made by Knapp and Lemmi (2014). The results here support these calls. Thoughts are very important for our current life satisfaction, similar in effect to that of our physical health. Furthermore, the analysis above has shown that our thoughts about the future can be responsible for a larger impact on well-being than such well-known causes of reduced life satisfaction as unemployment.

Identifying the association between the thoughts an individual has about the future and life satisfaction is a difficult task. The key right hand side variables may reflect an individual’s mood, their personality, and may well be endogenous with or to life satisfaction. These possibilities were using generally well-understood models, these possibilities have been addressed and the hypothesised association between optimism and pessimism, and life satisfaction have been shown to remain. Additional research will be needed to find out what is driving this association. Within the economic literature, there are two potential interpretations for the found relationship between current life satisfaction and the future. The first is that current life satisfaction includes the notion of savouring or anticipation of what will happen in the future (as in, for example, Elster and Loewenstein (1992).Footnote 19 The second is that individuals, when asked about their life satisfaction, automatically calculate some sum of the life satisfaction that they predict that they will experience in future years (for example, Benjamin et al. (2021). The analysis above does not distinguish between these two interpretations but this might be something usefully taken on by future research.

Another avenue for future research is to investigate whether the impact of thoughts about the future might be different for individuals with different personality types. For example, introverts may be more affected by their thoughts about the future than extroverts. Other “Big Five” personality traits would also be interesting to investigate.Footnote 20 For example, how do optimism and pessimism affect life satisfaction for individuals with differing levels of neuroticism? Does being very conscientious have an impact on an individual’s thoughts on the future and their impact on well-being? Are these linked to the notion that optimism, for some people, reflects overconfidence? Other interesting questions are easily found. One relates to the finding that males are seemingly more affected by thoughts than females. Is it possible that this reflects a “breadwinner effect”, whereby males are more (on average) financially responsible for the family and their life satisfaction more keenly responds to their thoughts about the future? Future research can test this, along with different age cohort profiles and other subsamples via the use of interaction effects.

The analysis above has used overall life satisfaction, which is generally considered an evaluative measure of well-being. Future research could consider other measures of well-being. Perhaps more affect based (or even eudaimonic) measures of well-being have a larger or smaller association with perceptions of the future. This would be interesting to find out and could be combined with an analysis of the ‘Big Five’ personality types when researching an association between well-being and perceptions of the future. Finally, it would be interesting to learn about how the general negative impact of pessimism found here is driven by domain-specific concerns like, for example, the fear of unemployment. Similarly, an individual’s degree of optimism or pessimism may play a substantial role in moderating the non-pecuniary aspect of the loss of well-being in becoming unemployed, as mentioned in the introduction, and may well affect how quickly someone finds employment again.Footnote 21 The combination of subjective factors can help aid better the understanding of objective phenomena and is likely a fruitful path for future research.

5 Concluding remarks

This investigation has provided evidence that peoples’ perceptions of the future in general, and particularly, their fears regarding the future have a substantial impact on their current life satisfaction. This was found via three separate regression models (OLS, FE, and dynamic GMM) to take into account unobserved individual heterogeneity as well as to recognise, and appropriately deal with, the possibility that such perceptions might be endogenous. Being pessimistic about the future has a large negative effect on well-being, larger than such well-known and studied factors as being unemployed. In the results of Sect. 3, the largest negative impact on life satisfaction is pessimism about the future (similar in size to the positive effect of reported very good health compared to poor health). This result, and particularly its size, is important.

The inclusion of an individual’s thoughts about the future in an assessment of well-being is also important because, as the results above indicate, this inclusion leads to a higher level of explained variation of life satisfaction in the models. It is often difficult to know what to include in multivariate regressions of life satisfaction, and data often plays a key role in what can be chosen. With current datasets, it may not always be possible to include thoughts about the future in well-being models. Where possible, the results of this analysis suggest that thoughts about the future should be included. Given the size of the effect, the likely gender difference, and the role in explaining variation in life satisfaction, thoughts about the future should be considered for inclusion. Even if they are not of direct interest, they are likely to be important control variables.

Economics deals largely with objective factors (unemployment, marriage) and assesses their direct association with well-being. The analysis above indicates that subjective factors are also important and should also be considered, whether directly or as a control variable, in future investigations of well-being. This may mean that future datasets should also include more subjective questions: the inner life of individuals is likely to be as important for satisfaction with life as objective factors. An enhanced understanding of life satisfaction needs to include both subjective and objective elements of an individual’s life. As is very often the case, more research would be useful and informative.

Notes

A reviewer has suggested that a possible reason for the differing sizes of these coefficients is that optimism is likely more nuanced than pessimism and thus potentially subject to attenuation bias.

As is explained below, due to the methods used and the desire for a consistent sample, not all of these years are used in the analysis.

This distinction between employed and government employed is not the same as private and public sector. Many individuals who work in the public sector would not be included in the government employed category because they are not ‘beamte’ a special designation that has the benefits listed above. In short, the government employed are a special kind of public sector employee, with ‘tenured civil service’ being a loose equivalent.

Health is controlled for in these estimations via people’s subjective response regarding how healthy they are. However, the relationship between the optimism and pessimism dummy variables and life satisfaction is unchanged when this subjective measure is replaced with one for whether an individual has stayed in hospital overnight in the past year and whether they are disabled or not.

The discussion of, and results from, System General Method of Moments (GMM) are limited to Appendix 2. The first reason for this is that these results, fully supportive of those from the other methods, are not presented in the main text due to not being able to perform all the necessary diagnostic tests. Because of how often the questions are asked there is not enough annually consecutive information to perform the AR(2) test. The other diagnostic tests present no issues. This lack of annually consecutive information also mean that the instruments System GMM uses for estimation come from the time period when the question was previously asked (the second reason for the presentation in Appendix 2).

Though as explained below, direct comparisons of coefficients obtained from System GMM should not be made with OLS or FE.

Cluster robust standard errors on the level of the individual are applied to the estimates here and to the FE estimations below.

There is evidence that this is the case: previous research shows that changes of the big 5 personality traits after adolescence and before old age need a very long time and are of negligible size (Lucas and Donnellan 2011, Cobb-Clark and Schurer 2012). However, there is also opposing evidence with, for example, Boyce et al. 2013a finding individual level changes in the prevalence of the big 5 personality traits over time.

An exception is for males who are not in the labour market. With OLS, such individuals are found to be rather unhappy compared to employed individuals, and with FE estimation, there is no statistically significant difference between these two groups. An explanation for this difference is because ‘not in the labour market’ is a largely time invariant variable and cannot be estimated precisely with FE. A situation remedied in the system GMM model (see Appendix 2).

The biggest difference between the consistent sample and the full sample is a reduction in the number of individuals aged 61 plus in the consistent sample. In practice, the different samples are of little consequence: the full sample was used with everybody, and again with an upper age limit of 60, with very similar results to those for the consistent sample displayed above.

A result which supports the findings of Clark et al. (2008b) who provided evidence that employed individuals are less happy before they experience unemployment.

This finding is upheld when the reference category is quite pessimistic rather than quite optimistic.

A notable previous attempt to investigate loss aversion, income and life satisfaction was made by Vendrik and Woltjer (2007).

To some extent, this was addressed by the controls for future events (though this was only the immediate future, i.e. the next wave).

An investigation linking life satisfaction, optimism and pessimism and the ‘Big 5’ personality traits has been made with an Asian American student sample (Liu et al. 2016).

Instead of controlling for future events, future research could also investigate how likely pessimistic people are to become unemployed (or divorced and so on) in the future. This could be achieved in an analogous fashion to work that shows low job satisfaction predicts quitting behaviour at work (see, for example, Clark et al. 1998).

Furthermore, the standard test for serial correlation with panel data (Wooldridge 2002; Drukker 2003) rejects a null hypothesis of no serial correlation, providing evidence of dynamic misspecification in the standard static panel models typically estimated in the “happiness” literature. This evidence strongly supports a dynamic specification, which is an additional reason for our use of system GMM.

In all cases, the GMM estimations employed the twostep robust procedure that utilises the Windmeijer finite sample correction for the two-step covariance matrix. Without this, standard errors have been demonstrated to be biased downwards (Windmeijer 2005).

The low average observations per person means that the m1 test for second-order correlation – AR (2) – of the first differenced residuals cannot be performed.

Some studies in the “well-being” literature that misinterpret these diagnostic tests are discussed in Piper (2014).

The coefficient for the lagged dependent variable demonstrates that the model passes Bond’s (2002) informal test for a consistent dynamic estimator; namely, that it should be between the equivalent estimates from OLS and FE (outputs not shown but available on request).

References

Baumeister RF, Campbell JD, Krueger JI, Vohs KD (2003) Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychol Sci Public Interest 4(1):1–44

Becchetti L, Corrado L, Samà P (2013) Inside the Life Satisfaction Blackbox, CEIS Research Paper 259, Tor Vergata University, CEIS

Benjamin, D.J., Debnam, J., Fleurbaey, M., Heffetz, O., Kimball, M. (2021). What do happiness data mean? evidence from a survey of happiness respondents. NBER Working Paper, 28438

Boyce C, Wood A, Powdthavee N (2013a) Is personality fixed? personality changes as much as “variable” economic factors and more strongly predicts changes to life satisfaction. Soc Indic Res 111:287–305

Boyce C, Wood A, Banks J, Clark AE, Brown GDA (2013b) Money, well-being and loss aversion: does an income loss have a greater effect on well-being than an equivalent income gain? Psychol Sci 24(12):2557–3256

Clark AE (2018) Four Decades of the Economics of Happiness: Where Next? Rev Income Wealth 64(2):245–269

Clark AE, Georgellis Y, Sanfey P (1998) Job satisfaction, wage changes and quits: evidence from Germany. Res Labour Econ 17:95–121

Clark AE, Frijters P, Shields MA (2008a) Relative income, happiness and utility: an explanation for the Easterlin Paradox and other puzzles. J Econ Lit 46(1):95–144

Clark AE, Diener E, Georgellis Y, Lucas R (2008b) Lags and leads in life satisfaction: a test of the baseline hypothesis. Econ J 118(529):F222–F243

Cobb-Clark DA, Schurer S (2012) The stability of big-five personality traits”. Econ Lett 115:11–15

De Neve J, Ward GW, De Keulenaer F, Van Landeghem B, Kavetsos G, Norton MI (2018) The asymmetric experience of positive and negative economic growth: global evidence using subjective well-being data. Rev Econ Stat 100(2):362–375

Elster J, Loewenstein G (1992) Utility from memory and anticipation. In: Loewenstein G, Elster J (eds) Choice over time. Russell Sage Foundation, pp 213–234

Forgeard MJC, Seligman MEP (2012) Seeing the glass half full: a review of the causes and consequences of optimism. Prat Psychol 18:107–120

Frijters P, Liu AYC, Meng X (2012) Are optimistic expectations keeping the chinese happy? J Econ Behav Organ 81(1):159–171

Gambaro L, Marcus J, Peter F (2019) School entry, afternoon care, and mothers’ labour supply. Empir Econ 57:769–803

Goebel J, Grabka M, Liebig S, Kroh M, Richter D, Schröder C, Schupp J (2019) The German socio-economic panel (SOEP). Jahrbücher Für Nationalökonomie Und Statistik 239:345–360

Greene W (2008) Econometric Analysis, 6th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey

Grözinger G, Matiaske W (2004) Regional unemployment and individual satisfaction. In: Grözinger G, van Aaken A (eds) Inequality: new analytical approaches. Metropolis, Marburg, pp 87–104

Hainmueller J (2012) Entropy balancing for causal effects: a multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Polit Anal 20(1):25–46

Hainmueller J, Xu Y (2013) Ebalance: a stata package for entropy balancing. J Stat Softw 54(7):1–18

Haucap J, Heimeshoff U (2014) The happiness of economists: estimating the causal effect of studying economics on subjective well-being. Int Rev Econ Edu 17:85–97

Hetschko C, Schöb R, Wolf T (2020) Income support, employment transitions and well-being. Labour Econ 66:101887

Ho MY, Cheung FM, Cheung SF (2010) The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting well-being. Personality Individ Differ 48(5):658–663

Kleiman EM, Chiara AM, Liu RT, Jager-Hyman SG, Choi JY, Alloy LB (2017) Optimism and well-being: a prospective multi-method and multi-dimensional examination of optimism as a resilience factor following the occurrence of stressful life events. Cogn Emot 31(2):269–283

Knapp M, Lemmi V (2014) The economic case for better mental health. In: Davies S (ed) Annual report of the chief medical officer 2013, public mental health priorities: investing in the evidence. Department of Health, London, UK, pp 147–156

Lang FR, Weiss D, Gerstorf D, Wagner GG (2013) Forecasting life satisfaction across adulthood: benefits of seeing a dark future? Psychol Aging 28(1):249–261

Layard R (2013) Mental health: the new frontier for labour economics. IZA J Labor Policy 2(1):1–16

Lucas RE, Donnellan MB (2011) Personality development across the life span: longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. J Pers Soc Psychol 101:847–861

Lui PP, Rollock D, Chang EC, Leong FTL, Zamboanga BL (2016) Big 5 personality and subjective well-being in Asian Americans: testing optimism and pessimism as mediators. Asian Am J Psychol 7(4):274–286

Mogilner C, Kamvar S, Aaker J (2011) The shifting meaning of happiness. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2(4):395–402

Osberghaus D, Kühling J (2016) Direct and indirect effects of weather experiences on life satisfaction: which role for climate change expectations? J Environ Planning Manage 59(12):2198–2230

Piper AT (2022) What does dynamic panel analysis tell us about life satisfaction? Review of Income and Wealth. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12567

Piper AT (2014) The benefits, challenges and insights of a dynamic panel assessment of life satisfaction, MPRA Paper 59556. University Library of Munich, Germany

Roodman D (2009a) How to do xtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. Stand Genomic Sci 9(1):86–136

Roodman D (2009b) A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 71(1):135–158

Senik C (2008) Is man doomed to progress? J Econ Behav Organ 68:140–152

Stutzer A, Frey B (2012) Recent developments in the economics of happiness: a selective overview, IZA discussion papers 7078, Institute for the study of Labor (IZA)

Stutzer A, Frey BS (2006) Does marriage make people happy, or do happy people get married? J Soc-Econ 35:326–347

Vendrik MCM, Woltjer GB (2007) Happiness and loss aversion: is utility concave or convex in relative income? J Public Econ 91:1423–1448

Windmeijer F (2005) A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics 126:25–51

Winkelmann L, Winkelmann R (1998) Why are the unemployed so unhappy? evidence from panel data. Economica 65(257):1–15

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Nick Adnett, Amina Ahmed Lahsen, Geoff Pugh and two anonymous reviewers for useful comments. This article has also benefited from comments from seminar audiences at the Europa-Universität Flensburg and the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) in Berlin. The German data used were made available by the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) at the DIW. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. I declare no conflict of interest nor any other ethical issues.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Results from system GMM analysis

Fixed effects estimates are conditioned on the individuals in the sample. Hence, the results cannot be generalised out of the sample. This issue does not arise in System GMM estimation; because the individual fixed effects are randomly distributed as part of the error term, results are generalizable to a larger population (assuming the sample is representative). However, the random effects approach to estimation entails the corollary that any independent variable correlated with these unobserved individual effects is endogenous, as is the lagged dependent variable in a dynamic model by construction. Moreover, a second source of potential endogeneity is simultaneity between optimism/pessimism and subjective well-being, such that they continuously condition one another. The main advantage of system GMM estimation is the ability to address the potential endogeneity of our variables of interest by exploiting the time-series depth of panel data to generate internal instruments for potentially endogenous variables. Here, “system” refers to two equations: one in which differenced variables can be instrumented by lagged levels and one in which variables in levels are instrumented by lagged differences (Arellano and Bover, 1995; Blundel and Bond, 1998; Roodman, 2009a and 2009b). External instruments can also be used, but the ability to address potential endogeneity only with internal instruments is a huge advantage when analysing survey data that lacks variables providing valid instruments.

We also use system GMM for its typical application; namely, to estimate a dynamic model.Footnote 22 The addition of the lagged dependent variable controls for the past history of the model (Greene 2008, p.468) so that the estimated effects of the other explanatory variables represent contemporaneous associations. In addition, by taking into account the persistence measured by the estimated coefficient on the lagged dependent variable, it is possible to derive the long-run effects of each independent variable. This changes the interpretation of the results and means that the results obtained should not be compared with those obtained by OLS and FE estimation.Footnote 23 Table

10 presents the results along with the standard diagnostics. We use the default instrumentation—i.e. all available instruments—and treat only the variables of especial interest as endogenous. Alternative specifications and their outcomes are discussed below.

The diagnostic tests indicate that the model is statistically well specified.Footnote 24 The figures in the tables are p values and represent the probability of error when rejecting the null of exogenous over-identifying instruments.Footnote 25 Roodman (2009b) suggests that a ‘common sense’ level of 0.25 is more appropriate than the conventional 0.05. Here, the p values for the different Hansen tests are higher than this more demanding threshold and hence fail to reject the null hypothesis of exogenous over-identifying instruments.

As for the results, the biggest change from Tables 1 and 2 is for the “quite pessimistic” coefficients. With GMM analysis, and the related treatment of our variables of interest as endogenous, being quite pessimistic about the future is insignificantly different from being quite optimistic about the future (the omitted category) with respect to life satisfaction. However, being pessimistic about the future has a substantial and negative association with life satisfaction. Interestingly, perceptions about the future in general seem to play a larger role in the life satisfaction of men rather than women, though the life satisfaction of women is still substantially affected by such perceptions. Coupled with the previous tables, these results, and the increase in explanatory power they offer, indicate that, where possible, perceptions of the future should be modelled in standard well-being estimations. Accounting for endogeneity can be important too: when the likely endogeneity of the optimistic-pessimistic variables is taken into consideration, being quite pessimistic is insignificant for well-being but being optimistic or pessimistic is still important for satisfaction with life. Recall that these variables show contemporaneous effects (controlling for the history of the model), so being pessimistic about the future now is associated with lower life satisfaction now.

The coefficients obtained for the other explanatory variables are in line with expectations from previous results in the literature, and those presented in Tables 1 and 2. As examples, marriage is positively associated with life satisfaction, and unemployment negatively associated. Interesting to note is that government employees (‘Beamte’) are more satisfied with life than are other employees (the reference category). The lagged dependent variable deserves comment. Its uniformly high level of statistical significance supports our dynamic specification, and at just under 0.1 is in line with previous estimates arising from different samples and datasets.Footnote 26 These estimates indicate (as briefly mentioned above) that the direct influence of the past is small and that much of what makes up well-being is contemporaneous. For a more detailed discussion of the lagged dependent variable, its size, and robustness, in well-being estimations see Piper (2022).

The choices necessary for a dynamic panel System GMM analysis should, by necessity, be tested for robustness. Firstly, the choice about the potential endogeneity of different variables: the results in Table 10 reflect estimations where only the main variables of interest (optimistic, quite pessimistic, and pessimistic) are treated as potentially endogenous. Currently, there is little theoretical guidance within the literature to help the well-being researcher with this choice—a task for future research—but there is empirical evidence which suggests that marriage is likely to be endogenous to life satisfaction: Stutzer and Frey (2006), using the SOEP, show both that happier people get married and that marriage makes people happier. Treating the marital status variables as being potentially endogenous (as well as the optimism/pessimism variables) does not qualitatively change the results: optimistic people are more satisfied with life now than are quite optimistic people, and pessimistic people are less satisfied than are quite optimistic (and optimistic) people.

The second main choice a researcher can make is with regards to how many instruments should be employed. Table 10 estimates make use of all of the instruments available. Restricting the instrument set does not change the results found above. Moreover, a combination of making marital status endogenous and restricting the instrument count does not change the results. The results for the perception of the future dummy variables and their association with life satisfaction appear robust. And, as with OLS and both FE estimates, this remains so when some future events are controlled for (see Table

11).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Piper, A. Optimism, pessimism and life satisfaction: an empirical investigation. Int Rev Econ 69, 177–208 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-022-00390-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-022-00390-8