Abstract

This study empirically analyzes a comprehensive model of university identification. The study investigates the role of university brand personality (UP), university brand knowledge (UBK), university brand prestige (UBP) in improving university identification (UI) in terms of stakeholders. The study also explores whether UI elicited brand-supportive behaviors such as suggestions for improvements, university affiliation (UA), advocacy intentions (AI) and participation in future activities of stakeholders. The model is analyzed using data collected from local people, students and employees of a public university. A total of 1000 usable surveys were obtained. The structural equation modeling was used to analyze hypotheses. The study contributes to this literature by enhancing our understanding of under-researched university identification in higher education. The results show that UBK and prestige positively affect university identification. Additionally, university identification is positively associated with suggestions for university improvements (SUI), UA AI and participation in future university activities (FUA) of stakeholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The milestones of economic growth and competitiveness are higher education, research and innovation. At the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first century, the enrollment rate in higher education and, correspondingly, the demand for higher education increased. These developments led to increased diversity, flexibility, and mobility in higher education (Gunay, 2016), as well as increased competition among institutions.

The increased competition among institutions strengthens the need for these institutions to understand and manage a strong identification (Dholakia & Acciardo, 2014; Rauschnabel et al., 2016). Besides, decreasing government funding and tightening budgets have led to give importance to branding concept of universities (Stephenson & Yerger, 2014).

Brand concept in higher education dates back to the 1990s. Currently, the traditional university management model has changed, and there is a trend toward academic capitalism, especially in developed countries. Although universities are not as profit oriented as businesses, it is important that they, like businesses, are cost-effective and quality oriented. In addition, they should meet the needs and wants of individuals receiving training, and ensure the support of stakeholders (Aktan, 2007). Therefore, these institutions should increasingly use marketing and brand strategies commonly used in profit-making sectors to manage competition effectively (Alessandri, 2007; Balaji et al., 2016; Rauschnabel et al., 2016). Despite the increasing importance of higher education marketing and brand strategy, little empirical research exists on this subject (Bennett & Ali-Choudhury, 2009; Palmer et al., 2016; Sung & Yang, 2008; Thuy &Thao, 2017).

The brand identity and image are important to convince and support the notion of ‘value complementarity’ amongst stakeholders (Spry et al., 2020). Identification is the emotional glue and an important concept for organizations. University identification is a particular type of social identification and it enables individuals to increase their self-image by associating with the institution. Consequently, they support their institution and develop a long-term relationship with the institution.

However, few studies examined university identification. Besides, elements of university identification are unclear in higher education literature. As a consequence, the university identification in prior literature has become inconsistent. The antecedents and consequences of university identification have not achieved a consensus in the literature. Therefore, the study has two objectives: to explore the antecedents of university identification for various groups, and to explore the role of university identification in supportive behaviors by various groups. In accordance with these objectives, the study was conducted based on different samples (students, university employees and local people) to explore the antecedents [university brand personality (UP), university brand knowledge (UBK) and university brand prestige (UBP)] and consequences [suggestions for improvements, university affiliation (UA), AI, participation in future activities (FUA)] of university identification. The research question of the study was: What are antecedents and consequences of university identification?

The study aims to contribute to a better understanding of university identification and its relation to stakeholders through a comprehensive model neglected by previous studies. The study differs from previous studies by examining university identification in terms of students, employees and local people. Additionally, the UP in the study was measured using the UP scale developed by Rauschnabel et al. (2016). Previous research has examined brand personality. However, no study has examined brand personality using a developed scale for university in terms of holistic perspective. The study contributes to both literature and practice. The model could be used to build, improve, and enhance university identification by university managers as well as to extend the foundation of a holistic perspective on university identification literature.

The study adopts quantitative method to investigate antecedents and consequences of university identification. Data was collected through survey method. The survey was applied to 1000 participants in Turkey. Three studies were conducted with students, employees and local people. The paper was used structural equation modelling to test the hypothesized relationships. The paper is organized as: the next section provides the literature review; then, the research method and findings are outlined. Finally, the findings are discussed and the study is concluded with implications and future research directions.

2 Literature review

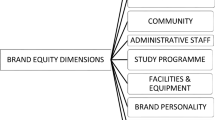

Branding has an important role as it enables institutions to differentiate themselves from their rivals. However, studies on branding are not sufficient in higher education. These are UP (Avinante et al., 2014; Opoku et al., 2008; Polyorat, 2011; Rauschnabel et al., 2016; Rutter et al., 2017; Simiyu et al., 2019; Watkins & Gonzenbach, 2013), university identification (Balaji et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2016; Rutter et al., 2016; Spry et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2019), brand prestige (Mael & Asforth, 1992; Sung & Yang, 2008), brand logo (Alessandri et al., 2006), brand community (McAlexander et al., 2006), university brand equity (Eldegwy et al., 2018; Kaushal & Ali, 2018), social media interaction (Rutter et al., 2016; Shields & Peruta, 2019), reputation (Heffernan et al., 2018; Khoshtaria et al., 2020), cocreation (Chalcraft et al., 2015; Dollinger et al., 2018; Fleischman et al., 2015; Robinson & Celuch, 2016), student-customer orientation (Hashim et al., 2020; Koris et al., 2015; Ng & Forbes, 2009), and touchpoints (Khanna et al., 2014).

Branding is a marketing practice. The marketing approaches in educational services are important and they include development, pricing, distribution and promotion of services for the needs and wants of stakeholders (Yamamato, 1997). The target customers of the university are students, funders, business and donors. Marketing issues and strategies applied by universities are differentiated for each customer group. For example, the prominent elements in marketing strategies for students are positioning, product/market planning, promotional campaigns, relationship development, social responsibility projects and sponsorship (Liu, 1998).

The number of universities has gradually increased over time, which has led to financial, quality, and competition problems. In response to these problems, universities have had to develop more effective marketing strategies. One such approach is for universities to advertise their rankings among other institutions as a quality indicator. This information is displayed on their web pages.

However, these rankings have not had any effect on students’ preferences (Rauschnabel et al., 2016). Rather, brand perception of educational institutions significantly affects individuals’ choices of educational institutions (Bock et al., 2014). In the study conducted by Belanger et al. (2002), the authors found that image and reputation had a great effect on the students’ university selection process. The findings of many studies on the factors affecting the university preferences of students support this situation (Avinante et al., 2014; Belanger et al., 2002; Cosar, 2016; Yaman & Cakir, 2017).

Being a brand in the field of education has to do with what the institution means and to whom the institution belongs rather than the product offered (Black, 2008). To become a brand in education, many educational institutions use common marketing techniques, including brand management (Nedbalová et al., 2014; Rauschnabel et al., 2016). These techniques include university preference fairs; billboard and poster works; TV, radio, and Internet advertisements; and promotional catalogs and other materials on university web pages (Kilic & Altay, 2018; Nedbalová et al., 2014).

Also, universities commonly use direct mail, advertising, catalogs and brochures, publicity and promotion, list visit programs, campus programs, and graduate support programs (Kotler & Fox, 1995). To establish a brand in higher education, an institution has to reveal the difference between itself and other institutions while meeting the needs and wants of the students, to give the students confidence and to protect the interests of successful students in the institution (Bennett & Ali-Chouldry, 2007). In this context, higher education institutions (HEI) have to give importance concepts such as brand image, brand personality, brand knowledge, suggestions for university improvements (SUIs), university affiliation, AI and participation in FUA of stakeholders.

It is important that a brand image is revealed by a university. The brand image needs to be measured for various stakeholders because it is a strategic issue. It is a fact that external stakeholders also have an impact on the success and image of the organization. Therefore, it is necessary to take the perceptions of these stakeholders into account when trying to understand and manage the brand perception of all stakeholders for the differentiation of educational institutions from their competitors (Balaji et al., 2016; Rauschnabel et al., 2016). “Brand is the interface between the organization’s stakeholders and its identity (Abratt & Kleyn, 2012).” In this context, university administrators should determine their current image and follow it. Secondly, answering the question “What kind of university do I want?” should reveal the image the university wants to achieve. Finally, the university should determine how it will achieve the desired image, starting from its current image, and should continuously measure whether it is creating this image by completing studies on this subject (Polat, 2009). Institution identification is composed of both the direct interactions of an individual and that individual’s psychological identification with an organization (Wilkins & Huisman, 2013). University identification based on social identity theory (Tajfel, 1978) enables individuals to increase their self-concept. Self-concept is comprised of personal identity and social identity. These identities relate to represent their answer to the question, ‘Who am I?’ (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Depending on this answer, individual’s supportive behaviors change. Social identity has been used to explain behavior of organization or consumer. University identification is a specific type of social identification. According to this, individuals define themselves as memberships of organizations (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). Few studies have been published on university identification. For example, university identification is found to affect the students/alumnis’ supportive behaviors toward the university (Abdelmaaboud et al., 2020; Mael & Asforth, 1992; Palmer et al., 2016; Stephenson & Yerger, 2014). According to Abdelmaaboud et al. (2020), students’ advocacy intention affects student satisfaction, and trust as well university identification. Besides, Palmer et al. (2016) find that antecedents of brand identification are academic and social experince for alumni. However, Stephenson and Yerger report that antecedents of brand identification are prestige, satisfaction and interpretation of brand for alumni. Moreover, Yao et al. (2019) state internal brand identification is linked with brand citizenship behaviors (see Table 1).

In this study, consequences of UI are suggestions for improvements, UA, AI, participation in FUA whereas antecedents of university identification are UP, UBK and UBP. These are explained below.

2.1 Antecedents of university identification

UP is defined by personality traits as regards a brand (Aaker, 1997). Rauschnabel et al. (2016) identified six distinct UP dimensions: (1) prestige (accepted, leading, reputable, successful, considerable); (2) sincerity (humane, helpful, friendly, trustworthy, fair); (3) appeal (attractive, productive, special); (4) liveliness (athletic, dynamic, lively, creative); (5) conscientiousness (organized, competent, structured, effective); and (6) cosmopolitan quality (networked, international, cosmopolitan). To measure UP, different scales have been developed by different researchers (Aaker, 1997; Aksoy & Ozsomer, 2007; Ekinci & Hosany, 2006; Geuens et al., 2009). The subject is generally examined in terms of different fields of education. To create brand attractiveness in the digital age, the focus of the brands should be human-centered marketing, because the varieties of human character are reflected by the most differentiated brands. These brands both empathize with and deeply explore the link between digital age and people (Kotler et al., 2017). Stephenson and Yerger (2014) report that the UP has a positive effect on identification. However, Balaji et al. (2016) find that UP did not have a significant effect on university identification. The relationship reported is generally positive in previous literature (Kim et al., 2001, 2010; Wu & Chen, 2019) although these studies differently reported the significance of the relationship between the two constructs. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1

University brand personality positively affects university identification.

Generally, UBK consists of stakeholders’ perceptions of a university with regard to various elements of crucial importance in the decision-making process (Baumgarth & Schmidt, 2010; Balaji et al., 2016). Few studies addressed the relationship between UBK and university identification (Balaji et al., 2016; Stephenson & Yerger, 2014). Balaji et al. (2016) report that UBK has a positive effect on university identification. UBK is examined generally indirectly in previous literature. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H2

University brand knowledge positively affects university identification.

UBP is defined as the relatively high status of the university (Mael & Asforth, 1992). Brand prestige is important for universities because of the affective responses and positive attitude of individuals (e.g., local people, university employees, and students) toward a university (Ahn & Back, 2018; Balaji et al., 2016). There is a positive relationship between brand prestige and university identification (Balaji et al., 2016; Han et al., 2019; Pinna et al., 2018; Stephenson & Yerger, 2014). While previous literature has collected the data from samples of students, this study collects the data from different sample groups (employees and local people as well students). Thus, this study aims at examining whether the findings change for students, employees and local people. The above discussion frames the following hypothesis.

H3

University brand prestige positively affects university identification.

2.2 Consequences of university identification

Making suggestions for improvement involves sharing ideas with an organization to contribute to the value creation process of an individual (Groth et al., 2004). The concept is important for an organization’s development, employee–customer motivation, and engagement (Balaji et al., 2016; Bove et al., 2009). Some researchers have examined SUI and have found that UI has a significant impact on suggestions (Balaji et al., 2016; Pinna et al., 2018). Few studies addressed the relationship between SUI and UI. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H4

University identification positively affects suggestions for university improvements.

Affiliation is the type of connection with an organization that leads to the use of things such as organizational logos, stickers, and merchandise (Johnson & Rapp, 2010; Philips et al., 2014). Affiliation is often studied by researchers, who have suggested that there is a positive relationship between UI and university affiliation (UA) (Balaji et al., 2016; Pinna et al., 2018). Generally, UA is greater among students who strongly identify with HEI (Balaji et al., 2016). The above discussion frames the following hypothesis.

H5

University identification positively affects university affiliation.

AI are represented by positive word of mouth and made up of the most important antecedents of customer engagement (Sashi et al., 2019; Stephenson & Yerger, 2014; Zeithaml et al., 1996). Positive word of mouth about an organization affects its success by helping it develop a positive organizational reputation (Bilgihan et al., 2018; Pinna et al., 2018; Sashi et al., 2019), and identification has a significant effect on individual advocacy (Abdelmaaboud et al., 2020; Balaji et al., 2016; Pinna et al., 2018; Stephen & Yerger, 2014). The above discussion frames the following hypothesis.

H6

University identification positively affects advocacy intentions.

Participation in the future brand activities of stakeholders relates to the willingness of stakeholders to attend university events and participate in activities sponsored by that organization (Bove et al., 2009; Balaji et al., 2016; Pinna et al., 2018). In the higher educational institution context, some studies have indicated that UI decides the strength of the students’ intentions to participate in FUA at the university (Balaji et al., 2016; Pinna et al., 2018). The above discussion frames the following hypothesis (see Fig. 1). Figure 1 should be below of H7. They should relocate (h7 and fig1)

H7

University identification positively affects participation in future university activities.

3 Method

Data were collected from Turkey over a period of 3 months in 2018. A total of 1000 surveys were completed using web-based survey. The link to web-based survey was sent to the employees and students e-mail. In addition, the survey link was distributed to local people via social networks and researchers. Data was collected using convenience sampling for local people. Besides, multiphase sampling was used to obtain data of students and employees. For sampling to be created using multi-stage sampling technique; both the number of students in units from the Student Affairs Department and the number of personnel in the units from the Personnel Department were requested and the sample was determined in proportion to these numbers (Appendix A and B). The survey consists of general demographic characteristics of participants and eight latent constructs (Appendix C). These are UBK (VIF ≤ 10; max. Conditional Index CI ≤ 30; 4 items) from Baumgarth and Schmidt (2010); university brand prestige (UBP/α: 0.77) from Mael and Asforth (1992); UI (all C.R. ≥ 0.95 and all AVE ≥ 0.64) from Jones and Kim (2011); SUI (C.R: 0.77 and AVE: 0.80) from Bove et al. (2009); UA (α: 0.83) from Johnson and Rapp (2010); AI (α ≥ 0.68;) from Zeithaml et al. (1996) and Stephenson and Yerger (2014); participation in future university activities (FUA/C.R: 0.94 and AVE: 0.67) from Bove et al. (2009) and UP (all C.R ≥ 0.77 and all AVE ≥ 0.53) from Rauschnabel et al. (2016). All the items were adapted from relevant literature and measured using a 7-point Likert scale. The scales were adapted to each group of respondents. The face and content validity of the constructs was assessed by five academic staff. The final survey was administered to students, employees and local people. The measurement model was constructed by a confirmatory factor analysis before the structural equation model was tested. Reliability and validity of constructs for each stakeholder was analyzed in different studies. The data obtained from the surveys were analyzed using structural equation modeling methods with the help of AMOS 22 program. Structural equation modeling has widely used in the behavioral and social sciences, as a modeling tool for the relation between latent and observed variables. The analysis technique could be seen as a unification of several multivariate analysis techniques (Brandmaier et al., 2013). Thus, structural equation modeling with a maximum likelihood was used to analyze the hypothesis.

3.1 Study 1

3.1.1 Sample

The study aimed to examine antecedents and consequences of university identification. A survey was conducted using students at a public university. A total of 450 usable surveys were obtained. A total of 233 students were female (52%) and 217 were male (48%). With respect to class level, 8% are 1st grade, 35.8% are 2nd, 24% are 3rd grade, 32.2% are 4th grade and graduate students. With regard to student’s nationality, 100% were Turkish. With respect to age, 58% were between ages 21 and 23.

3.1.2 Findings

The psychometric properties of all constructs exceeded the threshold (see Appendix D). The Cronbach alpha (α) of each construct is greater than 0.70, the composite reliability (CR) is greater than 0.80 (Hair et al., 2006) and the average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.50 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). α and CR values indicate internal consistency for the constructs. AVE values support discriminant validity for each construct (see Table 2).

Table 3 presents results of structural equation analysis. The results indicated an acceptable fit (χ2 = 1270.31; χ2/df = 3.32; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.92). As shown in Table 3, the results confirm most of the hypotheses (see Fig. 2).

UP was found to not affect university identification, which contradicts H1. However, UBK and UBP positively affected university identification, confirming H2 and H3. University identification was seen to have a significant impact on suggestions for the university, university affiliation, AI, and participation activities, confirming H4, H5, H6, and H7.

3.2 Study 2

3.2.1 Sample

The study was conducted with employees of a public university. In total, 273 employees participated in this study. A total of 179 employees were male (68.1%) and 84 were female (31.9%). Of the total sample, about 40% (104) were older than 40 years of age. Those under and 30 years were 20% (54) and 56% had completed postgraduate education.

3.2.2 Findings

Reliability and validity findings of all constructs are achieved greater than the threshold (see Appendix E). α value of all constructs is greater than 0.70, CR is greater than 0.80. AVE is greater than 0.50. The values indicate internal consistency and discriminant validity of the constructs (see Table 4).

Table 5 presents the results of structural equation analysis. The results indicated an acceptable fit (χ2 = 1198.22; χ2/df = 3.08; RMSEA = 0.08; CFI = 0.90). As illustrated in Table 5, the results confirmed all of the hypotheses. UP affects university identification, confirming H1. UBK and UBP have a significant impact on university identification, in support of H2 and H3. University identification affects suggestions for the university, university affiliation, AI, and participation activities. The findings support H4, H5, H6, and H7 (see Fig. 3).

3.3 Study 3

3.3.1 Sample

The sample consisted of local people from a city in Turkey. The survey was completed by 287 respondents. Male represented about 55% (155) of the respondents, 24% (69) of the sample was older than 40 years of age, and about 39% (113) had a lower education degree (less than or equal to secondary school).

3.3.2 Findings

Reliability and validity values of each construct are greater than the threshold (see Appendix F). α value of all constructs is ranged between 0.87 and 0.97; between 0.92 and 0.96 for CR; between 0.73 and 0.92 for AVE. The findings indicate internal consistency and discriminant validity of the constructs (see Table 6).

Table 7 presents the results of structural equation analysis. The results indicate an acceptable fit (χ2 = 1011.15; χ2/df = 2.61; RMSEA = 0.07; CFI = 0.92). As shown in Table 7, with similar findings in the employees’ sample, the results confirm all of the hypotheses. UP affects university identification, in support of H1. UBK and UBP have a significant impact on university identification, confirming H2 and H3. Finally, university identification has a positive impact on suggestions for the university, university affiliation, AI, and participation activities. The findings support H4, H5, H6, and H7 (see Fig. 4).

4 General discussion

4.1 Theoretical implications

This study contributes to identifying and validating the antecedents and outcomes of university identification in higher education. Empirical research on brand and brand identification in higher education are scarce (Stephenson & Yerger, 2014; Thuy & Thao, 2017). The study explores the university identification perspective of stakeholders through a comprehensive model neglected by prior studies. Few scholars have examined university identification in university stakeholders using a comprehensive model. Besides, the studies examine university identification concept in terms of either students or alumni. Thus, the study highlights the gap by exploring identification perception in university different stakeholders and expands prior literature in the areas of university identification by examining a new variable scale, UP, in higher education sector. Moreover, the study generates evidence of university identification from a developing country like Turkey in the higher education sector.

With globalization, higher education has shifted away from an elitist approach to the concept of massification. Especially since the 1980s, the acceleration of globalization has resulted in serious steps toward the marketing of information in the field of higher education and has led to the development of new educational models in this direction. At the same time, globalization has enabled students to initiate mobility toward universities ranked highly in the world of education. Although student mobility goes from developing countries to developed countries, developing countries participate in this process (Unal, 2019). Higher education is important in terms of a country’s competitiveness. Thus, countries want to increase the performance and competitiveness of their HEI. This perspective will lead universities to adopt a marketing approach more frequently and use marketing tools more effectively.

HEI have different customers such as students, government, local people, employers, donors etc. The universities focus on not only acquiring students but also retaining existing students. Since they want to get the most benefit from them both during education of students and after graduation. Alumni can give them financial and/or different supports (advisory boards to university, student services associate etc.) depending on the level of satisfaction during education life (Labanauskis & Ginevicius, 2017; Peppers & Rogers, 2011). Thus, the universities make an effort to build, maintain and develop the strong relationship with alumni. Recently, they have built peer-to-peer communities on their websites for drawing alumni and keeping the relationship. Moreover, some HEI give them free university-branded e-mail address and customizable web pages. The university has to be customer-oriented organizational culture such as private sector. The culture plays a critical role in the success of institutions. The customer-oriented university satisfies its stakeholders and ensures their loyalty (Peppers & Rogers, 2011). The stakeholders who with different expectations, needs and experience play a different critical role in the improvement of quality education and the university (Asiyai, 2015). For example, employees want to have appropriate working environment, participation in international programs and projects. They contribute to their studies, R&D activities, internationalization and communication in higher education sector. Thus, university identification perception of existing employees contributes to their retention. Besides, positive perception of university identification attracts high-qualified employees (Labanauskis & Ginevicius, 2017). Additionally, educational works can be developed with the energy and skill of the local people. Therefore, higher education sector as private sector is important stakeholder management. By concentrating on stakeholders’ management, co-creation could develop commitment and ownership of the branding and prove how distinctive attributes of an institution are drowned externally (O’Connell et al., 2011). To manage stakeholders, universities constitute stakeholders map and make communication programme according to the map. The center of the stakeholder categories are the students who are affected by the institution and those who work in the academic and administrative units (Hostut, 2018). Therefore, the study is considered some importance stakeholders and university identification concept examine students, employees and local people.

The current study investigates university identification from a holistic perspective in the higher education sector in Turkey. The findings show that UBP and knowledge are key antecedents of university identification for students. This is consistent with the work of Balaji et al. (2016). Similarly, Pinna et al. (2018) find that UBP has a significant impact on university identification. The most determinant element of university identification is UBP. The finding is not consistent with Balaji et al. (2016), who found that the most determinant element of university identification is UBK. The findings of the study also confirmed that university personality is not a significant predictor of brand identification. The finding is consistent with Balaji et al. (2016). The results additionally reveal that university identification affects students’ supportive behaviors toward the university. The finding is consistent with Abdelmaaboud et al. (2020), Spry et al. (2020) and Pinna et al. (2018). Besides, some studies reveal that there is a similar relationship for alumni (Palmer et al., 2016; Stephenson & Yerger, 2014; Mael & Asforth, 1992). The influence on students’ advocacy intention of university identification is higher than other three variables. The finding also corroborates the work of Balaji et al. (2016). Similarly, UBP is the most important part of university identification in terms of both employees and local people. Comparing to stakeholders, brand prestige concept is more important to students than other stakeholders. In addition, students are more eager to provide SUI. This result is normal, as university development will support their prestige perception. When the analysis results are examined, it can be said that the relative importance of the variables differ in terms of stakeholders. In addition, university identification affects supportive behaviors by university stakeholders (employees and local people). The finding is consistent with Spry et al. (2020). However, the findings show that UP is one of the main determinants of university identification for both stakeholder groups (employees and local people).

4.2 Managerial implications

The findings have important managerial implications. For managers, it is important to determine how a higher education institution is evaluated by its target audience and stakeholders, to reveal the importance of the university identification of the institution in students’ preference and to focus more on branding efforts. Thus, managers of HEI must develop university identification. If a university has a strong identity, it will be more likely to provide advocacy or support for development by students, employees and local people on any platform (Palmer et al., 2016; Stephenson & Yerger, 2014; Sujchaphong et al., 2015). There are also research findings in the literature that a strong UP perception, which is critical to university identity, affects students’ brand love, word-of-mouth communication, and supportive activities toward the university (Polyorat, 2011; Rauschnabel et al., 2016; Sung & Yang, 2008). In addition, the perception of the high prestige of universities empowers students, staff and local people to have more self-esteem as well as positive self-perception. Thus, university managers should carefully plan from a holistic perspective when they plan university brand; they should implement a plan and control it. In particular, university managers should evaluate their institution’s current position and consistently develop a stronger brand position (Celly & Knepper, 2010), using social media interactively in their brand activities. However, social media alone is not necessarily the most important part of branding activity. The success of brands depends on information about physical characteristics, actions they take, and consumers’ emotional responses and evaluations (Hollis & Brown, 2011). To develop a strong brand, one must first discover why customers buy and rebuy a particular product. In this direction, marketing experts ask some questions while evaluating. These questions are as follows: (i) What is the brand’s position in the market? (ii) What are the objectives? (iii) What is being done to improve the brand and the sector in which it exists? (iv) What are the strengths and weaknesses of the brand? (v) What opportunities should be followed first? Where are the possible pitfalls? The answers to these questions help marketers to achieve strong brand positioning (Clow & Baack, 2016). However, the branding of universities is not an easy process. The branding of a university should identify its products and services within the framework of a brand, identify and code these products and services, and use these identities and codes in university presentations (Coulon, 2007).

4.3 Limitations and future research directions

Like all studies, this study has limitations. First, university identification was examined in public HEI. Future studies could examine private universities or could compare different types of HEI or subbrands (campuses, schools, different teams, etc.). Future research could also look into a university with a different history and different positions. Second, the findings refer only to Turkey, and antecedents and consequences of university identification might differ elsewhere. Third, the study was conducted among university students, employees, and local people, thus limiting the generalizability of findings to other stakeholders such as funders, businesses, potential students, and alumni. Future research could examine university identification perception of other stakeholders. Fourth, the study was a cross-sectional project. Therefore, future studies can be designed to reveal a causal relationship between variables over time. Finally, future researchers could test constructs and/or alternative models of university identification.

References

Aaker, J. L. (1997). Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research, 34(3), 347–356.

Abdelmaaboud, A. K., Peña, A. I. P., & Mahrous, A. A. (2020). The influence of student-university identification on student’s advocacy intentions: The role of student satisfaction and student trust. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1768613

Abratt, R., & Kleyn, N. (2012). Corporate identity, corporate branding and corporate reputations: Reconciliation and integration. European Journal of Marketing, 46(7/8), 1048–1063.

Ahn, J., & Back, K. J. (2018). Influence of brand relationship on customer attitude toward integrated resort brands: A cognitive, affective, and conative perspective. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(4), 449–460.

Aksoy, L., & Ozsomer, A. (2007). Türkiye’de marka kişiliğini oluşturan boyutlar [Dimensions that make up the brand personality in Turkey]. 12 Ulusal Pazarlama Kongresi (pp. 1–14). Sakarya: Sakarya Üniversitesi.

Aktan, C. C. (2007). Change in higher education: Global trends and new paradigms. Higher education in the age of change. Yaşar University Press.

Alessandri, S. W. (2007). Retaining a legacy while avoiding trademark infringement: A case study of one university’s attempt to develop a consistent athletic brand identity. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 17(1), 147–167.

Alessandri, S. W., Yang, S. U., & Kinsey, D. F. (2006). An integrative approach to university visual identity and reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 9(4), 258–270.

Asiyai, R. I. (2015). Improving quality higher education in Nigeria: The roles of stakeholders. International Journal of Higher Education, 4(1), 61–70.

Avinante, M. D. P., Francisco, N. V., Tamayo, J. D., Borlongan, E. G., & Cruz, N. D. (2014). Brand personality of Centro Escolar University basis for developing strong brand identity. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, 4(11), 83–101.

Balaji, M. S., Roy, S. K., & Sadeque, S. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of university brand identification. Journal of Business Research, 69, 3023–3032.

Baumgarth, C., & Schmidt, M. (2010). How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically tested model of ‘internal brand equity’ in a business-to-business setting. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(8), 1250–1260.

Belanger, C., Mount, J., & Wilson, M. (2002). Institutional image and retention. Tertiary Education and Management, 8, 217–230.

Bennett, R., & Ali-Choudhury, R. (2007). Components of the university brand: An empirical study. Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Colloquiums of the Academy of Marketing’s Brand, Corporate Identity and Reputation SIG. Brunel University.

Bennett, R., & Ali-Choudhury, R. (2009). Prospective students’ perceptions of university brands: An empirical study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 19(1), 85–107.

Bilgihan, A., Seo, S., & Choi, J. (2018). Identifying restaurant satisfiers and dissatisfiers: Suggestions from online reviews. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 27(5), 601–625.

Black, J. (2008). The branding of higher education. Retrieved December 01, 2019, from http://www.semworks.net/papers/wp_The-Branding-of-Higher-Education.php

Bock, D. E., Poole, S. J., & Joseph, M. (2014). Does branding impact student recruitment: A critical evaluation. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 24(1), 11–21.

Bove, L. L., Pervan, S. J., Beatty, S. E., & Shiu, E. (2009). Service worker role in encouraging customer organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Research, 62(7), 698–705.

Brandmaier, A. M., von Oertzen, T., McArdle, J. J., & Lindenberger, U. (2013). Structural equation model trees. Psychological Methods, 18(1), 71–86.

Celly, K. S., & Knepper, B. (2010). The California State University: A case on branding the largest public university system in the US. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 15(2), 137–156.

Chalcraft, D., Hilton, T., & Hughes, T. (2015). Customer, collaborator or co-creator? What is the role of the student in a changing higher education servicescape? Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(1), 1–4.

Clow, K. E., & Baack, D. (2016). Bütünleşik reklam, tutundurma ve pazarlama iletişimi (Integrated advertising, promotion and marketing communication] (Çev. Ed. Gulay Ozturk), Nobel Akademik Yayıncılık Eğitim Danışmanlık Tic. Ltd. Şti.

Cosar, M. (2016). Üniversite tercihinde öğrencileri etkileyen faktörler [Affecting factors of students university preferences]. Eğitim Ve Öğretim Araştırmaları Dergisi, 5, 1–5.

Coulon, R. A. (2007). Branding your corporate university. In M. Allen (Ed.), The next generation of corporate universities. Wiley.

Dholakia, R. R., & Acciardo, L. A. (2014). Branding a state university: Doing it right. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 24(1), 144–163.

Dollinger, M., Lodge, J., & Coates, H. (2018). Co-creation in higher education: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 28(2), 210–231.

Ekinci, Y., & Hosany, S. (2006). Destination personality: An application of brand personality to tourism destinations. Journal of Travel Research, 45, 127–139.

Eldegwy, A., Elsharnouby, T. H., & Kortam, W. (2018). How sociable is your university brand? An empirical investigation of university social augmenters’ brand equity. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(5), 912–930.

Fleischman, D., Raciti, M., & Lawley, M. (2015). Degrees of co-creation: An exploratory study of perceptions of international students’ role in community engagement experiences. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(1), 85–103.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Geuens, M., Weijters, B., & Wulf, K. D. (2009). A new measure of brand personality. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(2), 97–107.

Groth, M., Mertens, D. P., & Murphy, R. O. (2004). Customers as good soldiers: Extending organizational citizenship behavior research to the customer domain. In D. L. Turnipseed (Ed.), Handbook of organizational citizenship behavior (pp. 411–430). Nova Science Publishers.

Gunay, D. (2016). Quality approaches and philosophical backgrounds in higher education. International conference on quality in higher education. Sakarya University.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Taham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Han, S. H., Ekinci, Y., Chen, C.-H.S., & Park, M. K. (2019). Antecedents and the mediating effect of customer-restaurant brand identification. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1603129

Hashim, S., Yasin, N. M., & Yakob, S. A. (2020). What constitutes student–university brand relationship? Malaysian students’ perspective. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1713278

Heffernan, T., Wilkins, S., & Butt, M. M. (2018). Transnational higher education: The importance of institutional reputation, trust and student-university identification in international partnerships. International Journal of Educational Management, 32(2), 227–240.

Hollis, N., & Brown, M. (2011). Küresel marka dünya pazarında kalıcı marka değeri yaratma ve geliştirme yöntemleri [The global brand: How to create and develop lasting brand value in the world market]. Brandage Yayınları.

Hostut, S. (2018). Türk üniversitelerin paydaş analizi [Stakeholders analysis of Turkish universities]. Erciyes İletişim Dergisi, 5(3), 187–200.

Johnson, J. W., & Rapp, A. (2010). A more comprehensive understanding and measure of customer helping behavior. Journal of Business Research, 63(8), 787–792.

Jones, R., & Kim, Y. K. (2011). Single-brand retailers: Building brand loyalty in the off-line environment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 18(4), 333–340.

Kaushal, V., & Ali, N. (2018). A structural evaluation of university brand equity dimensions: Evidence from private Indian University. International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management, 10(2), 1–20.

Khanna, M., Jacob, I., & Yadav, N. (2014). Identifying and analyzing touchpoints for building a higher education brand. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 24(1), 122–143.

Khostaria, T., Datuashvili, D., & Matin, A. (2020). The impact of brand equity dimensions on university reputation: An empirical study of Georgian higher education. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1725955

Kilic, A., & Altay, S. (2018). Marka ve marka kişiliği algısı: Bir üniversite örneği [Brand and brand perception: An example of university]. İşletme Araştırmaları Dergisi, 10(3), 670–692.

Kim, C. K., Han, D., & Park, S. B. (2001). The effect of brand personality and brand identification on brand loyalty: Applying the theory of social identification. Japanese Psychological Research, 43(4), 195–206.

Kim, H. G., Yu, H.-Y., & Kim, J.-H. (2010). The effect of brand personality on brand ıdentification, switching barrier and brand commitment. 로고스경영연구, 8(3), 159–182.

Koris, R., Ortenblad, A., Kerem, K., & Ojala, T. (2015). Student-customer orientation at a higher education institution: The perspective of undergraduate business students. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(1), 29–44.

Kotler, P., & Fox, K. F. A. (1995). Strategic marketing for educational institutions. Prentice Hall.

Kotler, P., Kartajaya, H., & Setiawan, I. (2017). Pazarlama 4.0: Gelenekselden dijitale dönüş [Marketing 4.0: moving from traditional to digital]. (Çev. Nadir Ozata). Optimist.

Labanauskis, R., & Ginevicius, R. (2017). Role of stakeholders leading to development of higher education services. Engineering Management in Production and Services, 9(3), 63–75.

Liu, S. S. (1998). Integrated strategic marketing on an institutional level. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 8(4), 17–28.

Mael, F., & Asforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123.

McAlexander, J. M., Koenig, H. F., & Schouten, J. W. (2006). Building relationships of brand community in higher education: A strategic framework for university advancement. International Journal of Educational Advancement, 6(2), 107–118.

Nedbalová, E., Greenacre, L., & Schulz, J. (2014). UK higher education viewed through the marketization and marketing lenses. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 24(2), 178–195.

Ng, I. C. L., & Forbes, J. (2009). Education as service: The understanding of university experience through the service logic. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 19(1), 38–64.

O’Connell, D., Kickerson, K., & Pillutla, A. (2011). Organisational visioning: An integrative review. European Journal of Marketing, 36(1), 103–125.

Opoku, R. A., Hultman, M., & Saheli-Sangari, E. (2008). Positioning in market space: The evaluation of Swedish universities’ online brand personalities. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 18(1), 124–144.

Palmer, A., Koenig-Lewis, N., & Asaad, Y. (2016). Brand identification in higher education: A conditional process analysis. Journal of Business Research, 69, 3033–3040.

Peppers, D., & Rogers, M. (2011). Managing customer relationships (2nd ed.). Wiley.

Phillips, J. M., Roundtree, R. I., & Kim, D. (2014). Mind, body, or spirit? An exploration of customer motivations to purchase university licensed merchandise. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 4(1), 71–87.

Pinna, R., Carrus, P. P., Musso, M., & Cicotto, G. (2018). The effects of student’s university identification on student’s extra role behaviors and turnover intention. The TQM Journal, 30(5), 458–475.

Polat, S. (2009). Yükseköğretim örgütlerinde örgütsel imaj yönetimi: Örgütsel imajın öncülleri ve çıktıları. [Image Management in Higher Education Institutions: Antecedents and Outcomes of Corporate Image]. The First International Congress of Educational Research, 1–3 Mayıs 2009, Çanakkale.

Polyorat, K. (2011). The influence of brand personality dimensions on brand identification and word-of-mouth: The case study of a university brand in Thailand. Asian Journal of Business Research, 1(1), 54–69.

Rauschnabel, P. A., Krey, N., Babin, B. J., & Ivens, B. S. (2016). Brand management in higher education: The university brand personality scale. Journal of Business Research, 69, 3077–3086.

Robinson, N. M., & Celuch, K. G. (2016). Strategic and bonding effects of enhancing the student feedback process. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 26(1), 20–40.

Rutter, R., Lettice, F., & Nadeau, J. (2017). Brand personality in higher education: Anthropomorphized university marketing communications. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(1), 19–39.

Rutter, R., Roper, S., & Lettice, F. (2016). Social media interaction, the university brand and recruitment performance. Journal of Business Research, 69, 3096–3104.

Sashi, C. M., Brynildsen, G., & Bilgihan, A. (2019). Social media, customer engagement and advocacy: An empirical investigation using Twitter data for quick service restaurants. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(3), 1247–1272.

Shields, A. B., & Peruta, A. (2019). Social media and the university decision. Do prospective students really care? Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 29(1), 67–83.

Simiyu, G., Bonuke, R., & Komen, J. (2019). Social media and students’ behavioral intentions to enroll in postgraduate studies in Kenya: A moderated mediation model of brand personality and attitude. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2019.1678549

Spry, L., Foster, C., Pich, C., & Peart, S. (2020). Managing higher education brands with an emerging brand architecture: The role of shared values and competing brand identities. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 28(4), 336–349.

Stephenson, A. L., & Yerger, D. B. (2014). Does brand identification transform alumni into university advocates? International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 11(3), 243–262.

Sujchaphong, N., Nguyen, B., & Melewar, T. C. (2015). Internal branding in universities and the lessons learnt from the past: The significance of employee brand support and transformational leadership. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 25(2), 204–237.

Sung, M., & Yang, S.-U. (2008). Toward the model of university image: The influence of brand personality, external prestige and reputation. Journal of Public Relations Research, 20(4), 357–376.

Tajfel, H. (1978). Social categorization, social identity and social comparison. In H. Tajfel (Ed.), Differentiation between social groups: Studies in social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 61–76). Academic Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson-Hall.

Thuy, V. T. N., & Thao, H. D. P. (2017). Impact of students’ experiences on brand image perception: The case of Vietnamese higher education. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark, 14, 217–251.

Unal, U. (2019). Internationalization policies of Turkey’s higher education area a research on Turkey gradues. Manas Sosyal Araştırmalar Dergisi, 8(1), 421–440.

Watkins, B. A., & Gonzenbach, W. J. (2013). Assessing university brand personality through logos: An analysis of the use of academics and athletics in university branding. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 23(1), 15–33.

Wilkins, S., & Huisman, J. (2013). Student evaluation of university image attractiveness and its impact on student attachment to international branch campuses. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(5), 607–623.

Wu, C. S., & Chen, T.-T. (2019). Building brand’s value: Research on brand image, personality and identification. International Journal of Management, Economics and Social Sciences (IJMESS), 8(4), 299–318.

Yamamato, G. T. (1997). Yükseköğretimde stratejik pazarlama planlaması yaklaşımı ve Türk üniversitelerinde stratejik pazarlama planlaması yaklaşımı üzerine bir araştırma [A research on strategic marketing planning approach in higher education and strategic marketing planning approach in Turkish universities]. Yayınlanmamış Doktora Tezi. Anadolu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Eskişehir.

Yaman, T. T., & Cakir, O. (2017). Üniversite tercihlerini etkileyen faktörlerin seçime dayalı konjoint analizi ile belirlenmesi [Determination of factors affecting university preference by choice based conjoint analysis]. MAKÜ—Uygulamalı Bilimler Dergisi, 1(1), 65–84.

Yao, Q., Martin, M. C., Yang, H.-Y., & Robson, S. (2019). Does diversity hurt students’ feeling of oneness? A study of the relationships among social trust, university internal brand identification, and brand citizenship behaviors on diversifying university campuses. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2019.1638482

Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. The Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46.

Funding

This research was funded by Aksaray University Scientific Research Projects Coordinatorship (Project No: 2018/018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: Bakirtas and Gulpinar, Analysis of data and writing findings of analysis: Gulpinar, Interpretation of data: Bakirtas and Gulpinar, Drafting of manuscript: Bakirtas.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no confict of interest.

Consent to participate

Consent to participate in the study is obtained from participants.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Aksaray University of Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bakirtas, H., Gulpinar Demirci, V. A structural evaluation of university identification. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 19, 507–531 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00313-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00313-3