Abstract

The aim of the present work is to validate a model of antecedents and consequences of university perceived value among graduates, and to analyse the moderating role of their level of involvement with Higher Education. Perceived value is proposed as the principal antecedent of perceived value, comprising four dimensions: teaching staff, infrastructures, administration staff, and support services. Overall satisfaction with the university and the overall image of the institution are taken as consequences, for the purpose of this study. The final sample – comprising 352 university graduates from all areas of knowledge – was obtained via computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). The theoretical model was estimated using Consistent Partial Least Squares (PLSc) and Multi-group Analysis (PLS–MGA). The results of the analysis confirm that perceived quality is a multidimensional construct formed by four distinct dimensions. It is found to determine perceived value, which, in turn, has a major influence on overall satisfaction and overall image of the institution, although the latter depends directly on satisfaction but not on perceived value in the case of graduates with a high level of involvement. These findings contribute to a better understanding of how university management can improve graduate satisfaction, via perceived quality and perceived value, and how graduate satisfaction is a major antecedent of overall image-formation. Further, the present results confirm that the extent of graduates’ involvement in Higher Education appears to moderate the effect of value on image, this moderation being greater among those graduates presenting a lower level of involvement. The conclusions from the research provide valuable information that can help guide university management in decision-making and strategy development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, the Higher Education (HE) sector has undergone something of a transformation at a global level (OCDE 2016). Over the past decade in Europe alone, this transformation has included higher rates of participation, internationalization, a growing awareness of knowledge-led economies, and increased international competition (Luque-Martínez et al. 2015). These changes have resulted in two central European policies: the Bologna Process and the Lisbon Strategy, including the Higher Education Modernisation Agenda (Neave and Veiga 2013; Sursock and Smidt 2015). The report ‘Trends 2010’ (European University Association) states that the employability of graduates has increasingly moved to the forefront of concerns at all levels, and poses particular challenges for Bachelor-level qualifications. At the same time, the report recognizes two issues of worldwide concern: the importance of student services and internal quality (Sursock and Smidt 2015).

Given the changeable nature of HE, managers and leaders in the sector are advised to take a user-centred approach. Increasingly, HE institutions (HEIs) recognize HE as a service industry and are therefore placing greater emphasis on client satisfaction (Hill and Motes 1995; Voss and Voss 2000; DeShields et al. 2005; Santini et al. 2017). Within this context, given the role of universities as social and economic drivers, the added value of HE comes under the spotlight. Hence, it is essential to keep abreast of the opinions and decision-making processes that students apply. Furthermore, a means of measuring the perceived value of universities, the degree of graduate satisfaction, and their impact on university image is vital to a better understanding of the perceptions of universities held by one key stakeholder groups in particular – namely, graduates. While such concepts are widely addressed in the literature on management and marketing (Grönroos 1989; Hu et al. 2009; Hemsley-Brown and Oplatka 2006), there are very few studies that deal with the case of universities, and fewer still that focus on this particular target public.

Studying perceived value is fundamental to effective management and decision-making within universities (Hannaford et al. 2005; Unni 2005; Ledden et al. 2011). More specifically, understanding graduate perceptions of the service they received whilst at university and their satisfaction with the education they were given can contribute to improving university performance and, ultimately, economic productivity. This knowledge can help in the decision-making process when endeavouring to attract more students (Beerli Palacio et al. 2002) and can improve the quality of the educational offer (Johnston 1995; Mai 2005), personal communication (Cuthbert 1996) and satisfaction with future work (Vila et al. 2007), thereby increasing perceived value (Aldridge and Rowley 1998; Sakthivel and Raju 2006).

While a number of studies have analysed graduate perceptions, the majority of works have focused on undergraduates (Kheiry et al. 2012; Dib and Alnazer 2013; Clemes et al. 2013). However, these works neither analyse concepts such as institutional image and satisfaction from the perspective of graduates who have already experienced the job market, nor do they measure the perceived value of HE in this segment of the population. Although there are one or two exceptions, they refer only to business graduates (Blázquez Resino et al. 2013) rather than the overall university population.

A university education has major consequences (Grummon 2012), from a social perspective, in terms of its effect on society and the economy of a country (Baumann and Winzar 2016), and from an individual perspective, in terms of a person’s future life path (Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada 2011). The decision to attend university is one of the most important choices a person may make in their lifetime, and as such is a high-involvement decision. As affirmed by Russell (2005), many students consider their choice to attend university as “the first class ticket of a lifetime”, given the monetary and quality-of-life benefits that a university degree supposedly confers.

It is within this context that an explanatory model of the formation of university perceived value among Spanish graduates is proposed, and its influence on satisfaction and institutional image analysed. The paper also identifies the moderating effect of HE involvement on the relationships between these concepts. In fact, the literature has yet to address this moderating effect on the relationships between perceived value, satisfaction, and university image among graduates – key variables for the on-going development of HEIs.

The main justifications for conducting this work are as follows:

-

The analysis it provides of the antecedents and consequences of perceived value (a concept that is under-addressed in the HE literature on graduate opinion). It is fundamental for universities to understand that HE offers value, rather than products or services. University students make enormous sacrifices, invest aspirations, and trust in the university qualification. They expect to be rewarded, in return, with a solid education, the acquisition of knowledge, and the chance to find gainful employment (Gielnik et al. 2015), to make good friends and to enjoy a future lifestyle in accordance with their expectations. The university therefore offers both emotional and functional value that will, to a great extent, determine satisfaction and image (Lai et al. 2012). In the present work, we seek to address these matters.

-

The detailed analysis of involvement as a moderating variable. Earlier works from the education sector have addressed the issue of involvement, but have not examined its moderating effect on value-formation.

-

The previous literature has focused on current students (at undergraduate and post-graduate level), while the present work examines the perspective of graduates who have already acquired experience of the job market and therefore have a broader vision with which to evaluate their university experience. They have a greater perception of value in terms of the benefits achieved in exchange for the sacrifice and effort they have made to achieve their qualification.

-

In the present work, we jointly analyse all areas of knowledge (business, engineering, humanities, health sciences, experimental sciences, and so on).

2 Literature review and research hypotheses

2.1 Perceived value in the Higher Education sector

Perceived value is considered to be the overall outcome of marketing activities. For Sinha and DeSarbo (1998), the notion of value is central to economic exchange and endemic to marketing, in which ideally both buyer and seller derive a value greater than each one relinquishes. The widely-acknowledged importance of perceived value in customer decision-making is due to its influence on intention to repurchase, intention to spread positive word-of-mouth, and willingness to pay a price premium; it is, according to Pihlström and Brush (2008), a predictor of people’s behavioural intentions (Chung and McLarney 2000; Turel et al. 2007; Fares et al. 2013).

Zeithaml (1988) defines perceived value as a consumer’s overall assessment of a product or service, based on their perception of what they ‘give’ and what they ‘receive’ in return. However, the conceptualisation of perceived value also involves other factors such as perceived cost, sacrifice, intrinsic and extrinsic attributes, and so on, that have been added since Zeithaml’s original definition. The composition of perceived value depends on the context and the characteristics of each service (Dodds 1991; Lin et al. 2005). Elsewhere, Sánchez et al. (2006) conceives perceived value as a dynamic variable, experienced before purchase, at the moment of purchase, at the time of use, and after use.

Hence, in the context of the HE sector, defined by Lovelock (1983) as a service that provides intangible actions in the minds of people, perceived value is configured as a complex process in which the benefits would be evaluated in academic, social, personal, and employment terms, while the sacrifices would typically be either monetary in nature (enrolment fees, travel, accommodation, and so on) or based on personal effort. Personal values have been found to have only moderate explanatory powers in terms of forming students’ perceptions of received educational value (Ledden et al. 2007).

Given this scenario, we define ‘value’ within the university context as the net result of the graduate’s evaluation of perceived sacrifice and perceived benefit, taking into account academic, social, quality, and growth aspects and the ultimate outcomes in terms of employment and confirmation, or otherwise, of expectations.

2.2 Quality as the principal antecedent of perceived value

The concept of perceived quality has been the focus of much analysis throughout the literature, given the complexity of its definition and measurement (Parasuraman et al. 1985; Cronin and Taylor 1992; Lervik and Johnson 2003). Service quality has its origins in Expectation Disconfirmation Theory, as service quality is considered to be the difference between the consumers’ prior expectations of the outcomes of a given service and their perceptions of the service once they have received it (Grönross 1984; Zeithaml et al. 1988, 1996; Parasuraman et al. 1994; Gefen 2002). In general, high service quality is defined as the delivery of a service that meets or exceeds customers’ expectations (AMA Dictionary 2013. University quality is, therefore, a fundamental issue when evaluating students’ satisfaction with the teaching they have received (Athiyaman 1997, Stephenson and Yorke 2013).

Identifying the components of university quality is a complex task, given the wide variety of services simultaneously offered by the institution (Bigné et al. 2003). However, the literature has determined a number of key factors relating to this concept. The quality of teaching staff and staff-student interactions are the most highly valued aspects in the majority of studies and are considered as the fundamental dimension when evaluating their university experience (Miron and Segal 1978; Van Klaveren 2010; Teelken 2012). Lecturers are expected to motivate students, to give them new knowledge and aptitudes, and to prepare their students for future employment. They are responsible for creating a healthy learning environment as well as teaching new skills to their students (Dana et al. 2001; Hodge et al. 2011). By means of direct on-going contact with students and their use of a diverse range of teaching styles, teaching staff help students to fulfil their expectations (Appleton-Knapp and Krentler 2006). Indeed, in certain HEIs, social interaction between lecturers and students is considered vital for academic success and student satisfaction (Roberts and Styron 2010).

Moreover, contact with administrative staff and service-related aspects are also considered essential when determining the image of the university and satisfaction levels, as these aspects convey the true effectiveness of the university service (Harvey 1995). Administrative and service staff are therefore regarded as a further key dimension of university quality, as student support and guidance are some of their many functions (Bitner et al. 1990). Various different studies have concluded that staff are, in fact, the main component of university quality, as they have a significant influence on the final satisfaction of students (Joseph et al. 2005; Sohail and Shaikh 2004).

In this regard, the assessment of complementary and support services (sports, work placements, international relations, and so on) represents a key element of a complete overview of university quality (Borden 1995) as it will affect perceptions of the overall university service (Appleton-Knapp and Krentler 2006). Douglas et al. (2008) demonstrated the relationship between involvement and university satisfaction, finding that involvement led students to assess support services such as libraries and refectories more positively. Some years later, these authors demonstrated that, in addition to support services, communication and tangible elements such as cleanliness and comfort play a fundamental role in their perceptions of quality (Douglas et al. 2015).

Meanwhile, various other studies have highlighted the importance of infrastructures in forming satisfaction with the university, as these convey the external image of the institution (Delaney 2001; Thomas and Galambos 2004). Infrastructures bring together all the physical aspects of the institution related to teaching and sports facilities, complementary and management services, and university administration (libraries, IT facilities, teaching rooms, and so on). Infrastructures support both the academic as well as the non-academic activities of the institution (Peng and Samah 2006). A number of studies have demonstrated the importance of this component of university quality (Bigné et al. 2003; Joseph et al. 2005; LeBlanc and Nguyen 1997, 1999).

In short, we define university quality as the set of attributes relating to staff, services, infrastructures, and outcomes of the university experience, that lead to satisfaction or dissatisfaction among graduates in relation to their expectations.

In view of these assertions, university perceived quality may be conceived as a second-order construct comprising four dimensions. The following hypothesis is therefore proposed:

-

H1: University quality as perceived by graduates is a second-order construct, the components of which are the services offered by the teaching staff, the support services, the services delivered by administrative and service staff, and infrastructures.

The relationship between quality and perceived value has attracted the interest of innumerable academics and practitioners (Cronin et al. 2000; Tam 2004; Fornell et al. 1996; Hu et al. 2009; Dlačić et al. 2014). Though many conceptualizations of value have specified quality as the only ‘get’ component in the value equation, the consumer may implicitly include other highly abstract factors, such as prestige and convenience (Zeithaml 1988).

The relation of quality as an antecedent of perceived value has been corroborated in many other sectors such as tourism (Chen and Chen 2010; Jin et al. 2015), sports (Moreno et al. 2015), telecommunications (Kuo et al. 2009; Shukla 2010; He and Li 2011;) and health services (Choi et al. 2004).

Dlačić et al. (2014) demonstrated that perceived quality is the main antecedent of perceived value in HE. Martensen et al. (2000) also confirmed this relation in the university sector by considering value as personal effort expended and its rewards in working life. Brown and Mazzarol (2009) established that the quality of the personnel and the infrastructures predicted value. The influence of quality over value was upheld by Alves and Raposo (2010), Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo (2009), and, more recently, by Clemes et al. (2013).

Hypothesis 2 is therefore proposed:

-

H2: University quality, as perceived by graduates, has a positive influence on university perceived value.

2.3 Satisfaction as a result of perceived value

Rust and Oliver (1994) defined satisfaction as a reflection of the degree to which a consumer believes that possessing a product or their experience of a service evokes positive feelings. Zeithaml and Bitner (2003), in turn, defined it as the consumers’ assessment of whether a product or service has satisfied their needs.

In the context of HE, Elliott and Healy (2001) asserted that student satisfaction is a short-term attitude arising from the students’ evaluation of their own educational experiences. In turn, Elliott and Shin (2002) defined satisfaction as the students’ subjective evaluation of different outcomes (employment, social, and so on) and their experiences of education and campus life.

Meanwhile, a range of authors have alluded to the importance of combining the measurement of value with satisfaction (Woodruff 1997; Oh 2000). Lai et al. (2012) highlighted the importance of perceived value to universities when identifying the needs of students and endeavouring to focus on their satisfaction, ultimately, in order to achieve more effective models of education.

The academic literature has clearly demonstrated the positive influence of perceived value on satisfaction (Oliver 1980; Cronin et al. 2000; Athanassopoulos 2000; McDougall and Levesque 2000; Tam 2004). Munteanu et al. (2010) considered satisfaction to be the overall affective response of the consumer to the differences between expectations and the service they ultimately receive.

In their study on various types of service, McDougall and Levesque (2000) demonstrated the importance of perceived value in the validation of models of satisfaction with the service that is delivered. Wang (2010) and Yang and Peterson (2004) recognized the effect of customer perceived value on satisfaction, but found that this effect was moderated by switching costs.

The value chain is strongly linked to the dimensions of satisfaction and quality, as perceived by students (Rowley 1997; Aldridge and Rowley 1998; Sakthivel and Raju 2006; Petruzzellis and Romanazzi 2010). Vila et al. (2007) have also explored the effects of degree field choice on the distribution of occupational benefits, in terms of job satisfaction, while Ledden et al. (2007) considered that people perceive value within an overall social/cultural environment that defines and forms personal values. They concluded that value is a significant determinant of satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3 is therefore proposed:

-

H3: The perceived value of the university, based on the opinions of graduates, has a positive impact on their satisfaction with the institution.

2.4 Image as a consequence of perceived value

Image-formation has been studied in the business sector for some time (Dowling 1986) and is used to define a wide range of aspects and experiences. The university image is a set of adjectival interpretations about a university spontaneously associated with a given stimulus (physical and social) that has previously prompted a series of associations in individuals. Furthermore, such associations form a corpus of knowledge called beliefs or stereotypes. People form an image of an object via association chains or networks that are built up over a period of time, as a result of the stimuli they have accumulated. In short, image is the result of a subjective combination of physical and emotional elements that identify an organization (or a brand) and that distinguish it from other organizations of a similar nature. As Luque-Martínez et al. (2007) noted in relation to city managers, university managers need to have as much knowledge as possible of all the dimensions that might affect the university, in order to make informed decisions and draw up a strong strategic plan for the institution. They need to arrive at an acceptable assessment, which means they need to be fully aware of the present image of the university. They should then design the desired image and define the range of actions to achieve it. Indeed, the study of the university’s image is an important part of the diagnostic stage of the university’s strategic planning process.

According to Landrum et al. (1998), a university’s image is a valuable asset in the competitive arena, in an era of shrinking budgets and ever-increasing competition. This image influences a number of key decisions related to the university’s future, such as who will apply for a place, the local community’s attitude toward the institution, and perhaps the levels of both private and public funding available to it.

Various researchers in the field of HE have considered the image construct as a component of value (for example, Ledden and Kalafatis 2010; Ledden et al. 2011). Image as a component of perceived value refers to an image that is congruent with the norms of a consumer’s friends or associates and/or with the social image of the people that attend the university and their reputation according to the institution where they have studied (Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo 2007).

However, this work adopts the line followed by many other authors who state that the image is an independent construct that represents the perceptions of students towards the university (Beerli Palacio et al. 2002; Hu et al. 2009; Alves and Raposo 2010; Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo 2009; Duarte et al. 2012; Hemsley-Brown et al. 2016).

The relationship between perceived value and image has scarcely been addressed by the literature on HE, although it has been widely examined in other sectors (Beerli Palacio et al. 2002). For example, Hu et al. (2009) and Cheng and Lu (2013) in the tourism sector.

Certain studies assert that image is an antecedent of perceived value in HE (Johnston 1995; Brown and Mazzarol 2009; Sánchez-Fernández and Iniesta-Bonillo 2009; Alves 2011, Alves and Raposo 2007). However, Suwanabroma and Gamage (2008) concluded that an increase in university perceived value and service quality improves the university’s image in the eyes of the different stakeholders of the institution. For instance, Fram (1982) emphasized the importance of academic staff, the student’s predisposition, and their satisfaction as determinants for optimizing the image of the university. Clemes et al. (2013) also found a positive relationship between perceived value and image in Chinese universities, in consonance with studies from other educational contexts (Oliver 1996; Andreassen and Lindestad 1998; Chen and Tsai 2007; Hu et al. 2009) that confirmed that image was a consequence of perceived value.

Ivy (2001) established that students drew conclusions on the general image of an institution on the basis of impressions they had formed of its strengths and weaknesses, in accordance with the perceived value of the university qualification. Duarte et al. (2012), when considering image as a consequence of value, found that this association increased their perception, once they had acquired experience of working life.

In view of this finding, the following hypothesis is proposed:

-

H4: The perceived value of the university, based on the opinions of graduates, has a positive impact on the perceived image of the institution.

2.5 The influence of satisfaction on image

The formation of a favourable image has been analysed in various different service sectors, such as tourism (Beerli Palacio and Martin 2004, Fakeye and Crompton 1991), retail commerce (Bloemer and Ruyter 1998) and transport (Brunner et al. 2008). Such studies demonstrate the importance of image in organizational management and decision-making, yet this relationship is much less widely analysed in the world of HE (Beerli Palacio et al. 2002; Luque-Martínez and Del Barrio-García 2009; Schlesinger et al. 2016).

Landrum et al. (1999), citing Bess and Sheared (1994), discussed the impact of the process followed by U.S. News and World Report to report academic reputations. Parameswararan and Glowacka (1995) applied information-processing theories in relation to consumer decision-making and they examined the effect of the overall university image on the evaluation of its graduates. They suggested the existence of a halo effect of brand image or brand loyalty that influences consumers’ decisions and reduces the risk associated with the purchase decision when consumers face unfamiliar attributes.

University image influences perceptions of the institution and can affect the choice and behaviour of students, university staff, companies, and society in general. In this regard, Helgesen and Nesset (2007) and Marzo-Navarro et al. (2005) found that there was a positive relationship – as an antecedent – between satisfaction and image, whilst Nguyen and LeBlanc (1998) concluded that satisfaction will not necessarily lead to a favourable perception of image. So, the image of an HEI, in the eyes of students, does indeed shape its reputation to a large extent and can help to reduce the perceived risks associated with making the choice of which university to attend. A good image therefore enables HEIs to attract larger numbers of students and to retain them more easily (Beerli Palacio et al. 2002), as it is based on the strengths and weaknesses perceived by different segments of the population under study (Ivy 2001). Furthermore, a positive image among employers enhances their perception of the skills and knowledge of the graduations from a given university.

The effect of satisfaction on image is reflected by the extent to which the purchase or experience of a service improves the perception of the provider of the firm or institution, and increases the consistency of the positive experience over time (Johnson et al. 2001).

Although not focusing on perceived value, but rather on its main antecedent, namely quality, Alves and Raposo (2010) demonstrated the existence of a high correlation between satisfaction and image. Similarly, Helgesen and Nesset (2007) demonstrated the importance of achieving a good level of satisfaction with the institution in terms of forming a positive image of the university. Hu et al. (2009) studied the nature of the relationships between service quality, perceived value, image, and satisfaction. They concluded that the delivery of a quality service and value creation increase customer satisfaction and improve corporate image – the latter leading to higher levels of consumer intention. In this regard, analysing the relationship between satisfaction, perceived value and quality, Tam (2004) developed an integrated model covering these dimensions and demonstrated their positive effect in terms of predicting future purchases among consumers. In the HE context, Alves (2011) analysed and confirmed the importance of the relationship between image, satisfaction and perceived value. Elsewhere, a very recent work has confirmed the role of satisfaction as an antecedent of image in the HE context (Ali et al. 2016; Wong et al. 2016).

These works appear to demonstrate that a healthy level of satisfaction among students and/or graduates contributes to improving the institution’s image – arguments that therefore lead us to propose the following hypothesis:

-

H5: The satisfaction of graduates with the university services they have received has a positive impact on university image.

2.6 The moderating role of Higher Education involvement

Yet, quite aside from all of this accumulated knowledge, much-needed by HE management, it is also important to study the behaviours associated with the selection of a university in some depth and to monitor closely the evaluation of that choice by former graduates. In simple terms, these factors influence the reputation of universities and shape future management decisions as well as the choices made by future students. In this regard, a key question is whether the graduates’ assessment of their overall university experience and of the institution in particular may differ, depending on the degree to which each individual student was involved in HE.

The notion of involvement is a key concept within the field of human behaviour and consumer behaviour (Krugman 1965; Greenwald and Leavitt 1984, 1985; Zaichkowsky 1986; Astin 1999). It was introduced by Krugman (1965) to explain how the impact of a piece of persuasive communication depends on the processing effort that is required. Thanks to the seminal work of this author, the concept of involvement emerged as a key factor in any analysis of consumer behaviour and the effectiveness of marketing communications activities (Petty and Cacioppo 1986; MacKenzie et al. 1986; Mehta and Purvis 1997). The greater the involvement in a product, message or activity, the greater the attention and interest people will pay – which translates into more in-depth processing of the information they have received (Petty and Cacioppo 1986).

In studies on HE, the concept of involvement is approached from two perspectives. One of these approaches examines academic involvement and is focused on results (hours spent studying, attendance at lectures, and so on), which could be likened to situational involvement with the service (Aitken 1982; Duque and Weeks 2010; Wilkins et al. 2015). The other perspective considers involvement as the personal relevance or importance to the student, which corresponds to a lasting involvement (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2001). Involvement, in this latter approach, is understood to be the degree of commitment on the part of the student, according to their values and interests, as lasting involvement reflects a general and permanent concern for a certain service or sphere (Rothschild and Houston 1980). Laroche et al. (2003) contended that the involvement of an individual must be greater when faced with the choice of a doctoral or a university qualification in comparison with the choice of other services, given the relevance of the decision with regard to the future, as a consequence of the assumed risk of these decisions (Dholakia 2001), for example, the type of employment to which they may aspire.

In this study, the consideration of involvement within this second perspective is chosen, defining HE involvement as the extent to which graduates perceive their university to be personally relevant, based on their particular needs, values, and interests (Zaichkowsky 1986). Thus, perceptions of the university experience vary depending on the degree of involvement felt by individuals, as this shapes their commitment to the institution and their level of participation.

Greater involvement generally brings a greater sense of identification with the university, better grades and more extensive use of the institution’s services (Zeegers 2004). Involvement goes hand-in-hand with commitment, both of which affect the number of hours the individual is prepared to devote to studying, as well as the extent to which they feel identified with the institution and are interested in playing an active part in campus life. In turn, according to Hartman and Schmidt (1995) and Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro (2017), the satisfaction experienced by a university student will depend on the extent of their involvement in university life.

In short, participation and the willingness of students to take responsibility for their own self-management are therefore implicit aspects of the student involvement concept (Bailey 2013; Zhou and Cole 2016). Thus, the extent of student involvement may be expected to moderate the students’ perceptions of the quality of their university experiences to a significant degree. Student involvement may also be expected to moderate the effect of these perceptions on perceived value and the effect of perceived value on satisfaction and image.

The following hypotheses are therefore proposed:

-

H6: The extent of the involvement of graduates with their university experience (HE Involvement) moderates the relationships between perceived quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and image.

-

H6 1 : For graduates with a high level of involvement, the effect of perceived quality on perceived value will be greater than for graduates with a lower level of involvement.

-

H6 2 : For graduates with a high level of involvement, the effect of perceived value on satisfaction will be greater than for graduates with a lower level of involvement.

-

H6 3 : For graduates with a high level of involvement, the effect of perceived value on image will be greater than for graduates with a lower level of involvement.

-

H6 4 : For graduates with a high level of involvement, the effect of satisfaction on image will be greater than for graduates with a lower level of involvement.

No previous works have examined the moderating role of HE involvement on the formation of perceived value of the university and the relationships with other constructs such as satisfaction and image. The present work therefore makes a further contribution to the field of university management.

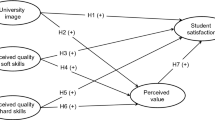

In light of the proposed hypotheses, a theoretical model was proposed. Perceived quality was measured as a second-order construct, through the following dimensions: quality of teaching staff (Q_t); quality of infrastructures (Q_i); quality of administrative staff (Q_a); and quality of support services (Q_s). The perceived quality of the university (PQ) determines perceived value (PV), which, in turn, determines university image (IMG) and satisfaction (SAT). The model was estimated for two groups of subjects: (1) graduates with a high level of HE involvement with the university during their undergraduate experience; and, (2) graduates with a low level of HE involvement (see Fig. 1).

3 Empirical study

3.1 Methodology and sample selection

The methodology chosen to pursue the research objectives, to test the hypotheses, and to estimate the theoretical model was a questionnaire-based quantitative study. The universe of study was the Spanish graduate population holding at least one degree qualification since 2003 onwards, thereby covering graduates from various Spanish universities. The rationale for selecting a time-frame of no more than 10 years since graduation was because earlier data would otherwise not be entirely comparable, in view of the changes in the Spanish university sector. No significant differences were found to exist (p < 0.05) in the evaluations that older graduates (2003–2007) made of the different items with respect to the more recent graduates (2008–2012). It can therefore be concluded that the time since graduation has no significant effect on graduates’ perceptions of the constructs under analysis. Nor were there any differences in graduate involvement according to the time that had elapsed since graduation.

There was also the issue of recall, in so far as respondents would have had to trawl their distant memory when responding to the questionnaire. A CATI (Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview) was employed to gather the data, with the assistance of a market research firm with broad experience in the field that was contracted by the researchers.

The sample was selected by means of random sampling based on age quotas and territorial representativeness. The final sample comprised 352 graduates. Assuming that the requirements of simple random sampling were met, there was an implicit error of 4.23%, at a confidence level of 95%. More specifically, the sample comprised 57.1% women and 42.9% men, 56.5% of whom were in employment or on student work placements and 43.5% were unemployed (see Table 1).

3.2 Measurements

An initial pre-test was prepared with 15 graduates chosen at random, with the objective of refining and improving the understanding of the measurement scales to be used. No question was eliminated or incorporated, but the drafting of different questions was modified, as was the approach to deciding how to incorporate questions in a negative sense, with the objective of avoiding responses by patterns. The results of the test allowed us to adapt the scales initially considered in previous studies to the scope of HE.

Table 6 lists the items comprising each of the different measurement scales in use. The research team adapted a range of scales taken from research on the university sector to measure the four dimensions of university quality: infrastructures (Bigné et al. 2003); teaching staff (Athiyaman 1997); administrative staff (Harvey 1995); and, support services (Douglas et al. 2008). All of these scales have been used in other recent studies (Douglas et al. 2015; Teeroovengadum et al. 2016).

With regard to measuring graduate perceived value, the researchers adapted the scale developed by Zeithaml (1988) and Cronin et al. (2000), which is used in studies to this day (Chiu et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2015; Pizam et al. 2016). As commented in the literature review, a unidimensional measure was chosen for this work, as proposed by many other authors (for example, Webb and Jagun 1997; Moosmayer and Siems 2012; Duarte et al. 2012; Dib and Alnazer 2013).

The scale developed by Cronin et al. (2000) was adapted to measure satisfaction with the university experience. The same scale has been used by Ledden et al. (2007) and Ali et al. (2016) in the HE context and by Eisingerich et al. (2014) and Prayag et al. (2017) in the services sector.

HE image was measured using the three-item, five-point Likert scale used by Luque-Martínez and Del Barrio-García (2009) in the context of HE and used recently by Da Costa and Pelissari (2016).

Lastly, HE involvement was measured by means of a five-item semantic differential scale based on a more extensive original scale developed by Zaichowsky (1985) and used by Flores et al. (2014) and Reychav and Wu (2015).

4 Results

4.1 Grouping the respondents of HE Involvement

Prior to estimating the proposed theoretical model, it was necessary to classify the respondents by their involvement with the university, using the distribution of the HE involvement score. As the scale presented a good level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.88), an indicator variable was calculated as the sum of the five items of the original variable. Bearing in mind the distribution of this sum variable, the graduates were classified into three groups, taking into account both the lower (33.33) and the higher percentile (66.66). It was decided that the middle interval should be excluded, so as to compare those graduates presenting a genuinely low level of involvement (LI: 125 subjects) with those who had a high level (HI: 134 subjects).

4.2 Analysis of the psychometric properties of the scales

Analysis of the psychometric properties of the scales was carried out by means of Partial Least Squares (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3 software (Ringle et al. 2014). In comparison with traditional covariance-based SEM (CBM) such as Lisrel, Amos, or EQS, a more powerful alternative analytical method has recently been developed, known as variance-based SEM or Partial Least Squares (PLS) (Chin 1998a, b; Lohmöller 1989; Wold 1982). Its advantages over CBM include the minimum assumptions made for measurement scales, sample size, and data distribution (Chin et al. 1996). The aim of PLS is to predict dependent variables, maximizing their explained variance. PLS-SEM relies on a non-parametric bootstrap procedure to test the significance of estimated path coefficients. Consistent PLS Bootstrapping with 5000 sub-samples was applied that performs the bootstrapping routine on the consistent PLS algorithm (PLSc) (Dijkstra and Henseler 2012; Dijkstra and Schermelleh-Engel 2013).

Table 2 shows the acceptable psychometric properties of the scales (items SAT4 and IMG3 were eliminated as they failed to present acceptable psychometric properties). All the loadings were significant in both groups (p < 0.01) and the values for Cronbach’s Alpha, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were above the acceptable cut-off levels (0.7, 0.8 and 0.5, respectively) (Hair et al. 1995; Del Barrio-García and Luque-Martínez 2012 in Luque-Martínez 2012; Henseler et al. 2016). Finally, discriminant validity was tested for each group, by implementing the criterion suggested by Fornell and Larcker (1981), by which the square root of the extracted variances must be greater than the correlations between the constructs (see Tables 3 and 4). It can be concluded, then, that the scales used presented good psychometric properties.

4.3 Test of hypotheses

Having evaluated the psychometric properties of the scales through the outer model, the proposed theoretical hypotheses were contrasted through the evaluation of the inner model obtained, after having applied consistent PLS Bootstrapping (Figs. 2 and 3). The results revealed that the perceived quality of the university was a second-order construct composed of the service offered by teaching and non-teaching staff, support services, and infrastructures – for both the high-involvement and the low-involvement group. All of the parameters were found to be significant, for both groups, and presented a magnitude of over 0.50 in all cases. The dimensions with the greatest weighting in the formation of perceived quality in both groups were those relating to the services delivered by administrative staff and the support services. Likewise, across all the dimensions of quality under analysis, the level of variance explained (R2) was fairly high – in all cases above 0.50, with the sole exception of the dimension relating to infrastructures. Hypothesis H1 can therefore be confirmed.

For both groups, the perceived quality of the university experience had a major influence on graduates’ perception of value (βPQ→PV_HI: 0.32, t: 3.92; βPQ→PV_LI: 0.26, t: 3.02), yielding support for hypothesis H2.

The relationship between PV and satisfaction was both significant and positive in both groups (βPV→SAT_HI: 0.50, t: 6.81; βPV→SAT_LI: 0.60, t: 11.42), providing support for H3.

In contrast, the relationship between PV and university image was only positive and significant, and in the direction proposed in hypothesis H4, for those graduates with a low level of involvement (βPV→IMG_LI: 0.16, t: 2.27), while it was found not to be significant for the more involved graduates (βPV→IMG_HI: -0.01, t: 0.18). This finding only offers partial confirmation of H4. The values above 0.50 in the R2 indicator for the ‘university image’ construct show that both PV and graduate satisfaction are indeed two major antecedents of university image-formation for this group.

Lastly, the image of the university according to graduates was directly and significantly determined in both groups via satisfaction (βSAT→IMG_HI: 0.67, t: 8.78; βSAT→IMG_LI: 0.64, t: 10.36), providing support therefore for Hypothesis H5.

Finally, H6 proposed a moderating effect of HE involvement on the different antecedent and consequent relations of perceived value. Table 5 shows the results of the PLS-MGA analysis of differences in the parameters between both groups. The results show that statistically-significant differences in both groups were only observed for the dimension pertaining to quality in terms of the services delivered by teaching staff, which was significantly higher (t: 1.75; p < 0.10) among graduates with a higher level of involvement with the university (βPQ→Q_t_HI: 0.78, t: 16.19) than among those presenting a lower level of involvement (βPQ→Q_t_LI: 0.62. t: 7.78).

H61 suggests that the effect of perceived quality on PV for graduates with a high level of involvement will be greater than for graduates with a lower level of involvement. The results demonstrate that although the estimated parameters are along the same lines as this hypothesis, in that they are higher in the higher-involvement group, the hypothesis cannot be entirely supported, as the outcome was not significant when testing for significant differences between parameters (t: 0.54; p > 0.10).

Likewise, there were no significant differences (t: 1.051, p > 0.10) between the two groups in the relation between perceived value and satisfaction, and the differences that did emerge operated in the opposite direction to the one hypothesized in H62; slightly higher for the LI group than for the HI group. Thus H62 could not be confirmed. In this case, the variance of this construct is explained (R2) via PV: 25% for the high-involvement group and 35% for the low involvement group.

H63 established that the effect of perceived value on image will be greater than for graduates with a lower level of involvement. The results show that this hypothesis cannot be confirmed as the comparative between-groups analysis reveals significant differences in this relationship, where the effect of PV on image is significantly greater among graduates with a lower level of involvement than among those with a higher level (t: 2.06; p < 0.05). In this case, it is also worth bearing in mind the indirect effect of PV on image, via satisfaction, which must be added to the aforementioned direct effect. The results, in terms of overall effect, in no way alter the previous findings as it is greater among graduates with a low level of involvement (TEPV→IMG_LI:0.54, t: 9.73) than for those with greater involvement (TEPV→IMG_HI:0.33, t: 4.35).

However, although the relationship between image and satisfaction was slightly greater in terms of its magnitude among the more involved graduates, along the lines predicted in H64, the test for differences between the parameters was not significant (t: 0.329; p > 10), and thus this hypothesis cannot be confirmed.

Finally, once the inner model had been examined and the hypotheses tested, the predictive power of the model was then evaluated. The explicative and predictive power of the model was tested using predictive relevance (Stone-Geisser-Q2) through a blindfolding procedure (Chin 1998a, b). Following the procedure recommended by Hair et al. (2014), the predictive relevance of the seven dependent variables in the model were judged to be acceptable, given that in all cases the Q2 indicator was positive (Figs. 2 and 3).

5 Discussion

The validated model allows us to establish that university quality consists of four components: support services, administrative staff, teaching staff, and facilities, the first two of which are the most important for the university graduate. This finding is along similar lines to those of other authors focusing on universities in countries other than Spain (Harvey 1995); it is contrary to the studies found in the literature review that highlight the importance of the role played by teaching staff in forming perceived university quality (Teelken 2012; Roberts and Styron 2010); it is compatible with the studies undertaken by Joseph et al. (2005) and Sohail and Shaikh (2004). The importance of services and administrative staff in our results may be because the first and last contact point of graduates is precisely with those members of staff, in addition to their importance in direct contact with students and their role in problem-solving of both a bureaucratic and an academic nature. Their management is fundamental for student orientation and support (Bitner et al. 1990; Bryce 2007) and their empathy has a notable impact on the emotional recall of the university experience (Stafford 1994; LeBlanc and Nguyen 1997).

Perceived quality determines perceived value, and this, in turn, has a decisive influence on satisfaction. The causal relationship between satisfaction and image is even stronger. A finding that implies a particularly interesting contribution to the literature, as it demonstrates that satisfaction is an antecedent of image – in contrast to the findings of other studies that point to image as an antecedent of satisfaction (such as Brown and Mazzarol 2009; Schlesinger et al. 2016). Another finding of particular interest is the fact that PV determines satisfaction exclusively among those graduates with a low level of involvement. Perceived value does not appear to have a direct and significant influence on image, but rather an indirect effect, via satisfaction, in the case of students with a high level of involvement. In other words, for university graduates with high involvement their formation of the image of the institution does not happen so much through their perceptions, but through the satisfaction that they might have acquired during their years of study i.e. their direct experience. Different studies (Ahmed et al. 1997; Matherly 2012) have considered the image projected by the university as a motive for their choice of institution, such that the image or reputation that the student has before entering the chosen university is more important than the image that they form once their time at university is over.

These relationships are not moderated by HE involvement with statistically significant differences. However, in most cases, for graduates with higher levels of involvement, the causal relationships are in general stronger. The literature suggests that subjects experiencing greater involvement are more aware of the institution, remember it more vividly, and take a more positive stance in terms of perceptions of quality and value of the institution.

In general terms, the proposed model is confirmed by the data. However, it appears that involvement has no relevant moderating effect on the relationships established in the study. As Laurent and Kapferer (1985) warned, the influence of involvement does not always translate into the expected effects, as there are different characteristics and antecedents that operate unevenly.

In the case of the present study, for those presenting lower levels of involvement, the relationship between PV and satisfaction is stronger, albeit not significantly so. The same holds true for the relationship between PV and image, where the difference between high and low significance was significantly greater among the less involved graduates. This finding is in line with those of Chen and Tsai (2008), in that the effects of perceived value are reinforced – it has a greater impact – for those who experience less involvement, because those with greater involvement seek out more information, analyse it in more depth, and are more demanding in their expectations. They are also more demanding in terms of satisfaction, which also influences the image they hold of the institution – a finding in tune with the assertions of Patterson and Spreng (1997) and Prayag and Ryan (2012), who also found that a greater level of involvement reduces the direct effect of perceived value on satisfaction and increases the indirect effects on image and attitudes.

Thus, the perception of the benefits received (securing a good job or a good salary, for instance) may be greater among those with a lesser degree of involvement who started from a lower set of expectations, leading ultimately to greater satisfaction and, in particular, a more positive image of the institution that is directly influenced by perceived value and indirectly influenced via satisfaction.

There are other studies that demonstrate that involvement and identification with the institution makes no contribution to image-formation – as asserted by Hennig-Thurau et al. (2001) – or ultimate satisfaction (Hartman and Schmidt 1995).

6 Conclusions and implications

The present study has sought to validate an integrated model of the antecedents and consequents of university graduate perceptions of value and to examine the moderating role of involvement with the university. It has demonstrated that the perceived quality of the university in this particular segment of the HE population comprises four significant dimensions, among which support services and administrative staff stand out, over and above the dimensions of teaching staff and facilities. One particularly important feature of the present research is that graduates made their assessment of their university experience some time after having completed their studies. Hence, it captures their perceptions of value (quality, satisfaction and image) that have lasted over the years. It is important that universities therefore maintain their links with graduates, as a means of reinforcing the institution’s PV and image. The results have shown that quality determines perceived value that itself determines satisfaction. In turn, satisfaction positively influences image. It has been demonstrated that the level of involvement has no influence on the relations established between these dimensions, although it is generally higher among those with high involvement, but without significant differences.

Universities can improve their image by improving graduate perceived value (via satisfaction). However, they should take more direct action on the expected benefits, in the case of those graduates with a lower level of involvement, by keeping in touch through ex-alumni associations beyond graduation. In the Spanish context, there tends not to be the kind of continuing, long-term link with graduates that exists in other contexts (such as is the case with English-speaking universities) as there is no tradition of alumni programmes or other such activities designed to foster on-going involvement of graduates with their alma maters.

Wilkins et al. (2015) demonstrated that identification with the HE institution leads to greater levels of satisfaction. Such identification brings with it greater involvement and commitment among students. Specifically, identification leads students to involve themselves directly and organizationally with the university, and even to commit themselves to remaining loyal to the institution (and thus make alumni donations in future) (Freeland et al. 2015).

In this regard, the university’s strategy should therefore be aimed at involving students from the very outset in its activities and processes, to achieve better results in terms of perceived quality, perceived value and satisfaction, all of which are key determinants of the university service (Oldfield and Baron 2000) and image. These findings demonstrate that the aim of increasing levels of involvement among students cannot be neglected once they graduate. They show how vital it is to maintain links with graduates and nurture a long-term relationship with them, taking a relational approach to projecting the university’s future image. It is therefore important to sustain relationships with graduates, keeping them up-to-date with activities that may be of interest (such as graduate opinion polls, university management indicators, or reports on the institution’s corporate social responsibility) and initiatives of value to them (for instance, lifelong learning opportunities or Massive Open Online Courses). It is also important to provide the necessary structures to support these relationships, such as graduate clubs and associations, and online social networks that foster on-going interaction between university and graduates.

Notably, this result is novel in the field of HE research, as involvement has, to date, always been analysed as the degree of participation or in terms of academic results, rather than – as in the present study – from the perspective of a lasting emotional involvement with the service itself.

The results of the present work respond to the needs detected in current trends within HE. The ‘Trends 2015’ report (European University Association) highlighted the need for studies or resources that enable service improvements in universities, given the growth of marketization in HE and the blurring of lines between public and private universities. Hence, it is important to understand the role of the university student as perceived by the university: learner or customer (Baumann et al. 2016).

In turn, the graduate’s perception of value is a fundamental aspect of their evaluation process, as value has a major emotional component. This concept is a key original feature of the present work. Students devote significant time and effort to achieving their qualification, and, in doing so, they seek to achieve a pay-off between the benefits and the sacrifices they make. Particularly within the current context of internationalization and globalization in HE, it is vital to know what value students place on their university qualification, depending in the institution and the university system of each country.

7 Limitations and future lines of research

Finally, it should be said that the present work has certain limitations. First, this study includes no other specific factors that contribute to university quality, such as social activities or campus ambience. Due to the diversity and complexity of the concepts used, the work is based on a summary measurement of perceived value and perceived quality. Second, the fact that graduates were asked about their perceptions of value or image several years after graduating (in some cases 10 years after) may be considered a limitation. That said, as the research was investigating their general perceptions only, the effect of the passage of time on individuals’ recall would be less marked. Third, the work only considers one geographical area, namely Spain.

Looking to the future, it would be interesting to validate the model in other university contexts or other countries, and for other stakeholders (such as current undergraduates, teaching staff, administrative and service staff, or businesses). It would also be interesting to explore the possibility of undertaking longitudinal studies according to the year of graduation. Other possible lines of research would be to examine the influence of a different typology of involvement, as suggested by Kumar et al. (1994) and Bloemer and Ruyter (1998), and to contemplate other possible moderating variables such as the graduate’s employment status at the point of participation in the study and the characteristics of their job (if employed), gender, or reason for selecting a course of study, among other variables.

References

Ahmed, K., Alam, K. F., & Alam, M. (1997). An empirical study of factors affecting accounting students' career choice in New Zealand. Accounting Education, 6(4), 325–335.

Aitken, N. D. (1982). College student performance, satisfaction and retention: Specification and estimation of a structural model. The Journal of Higher Education, 53(1), 32–50.

Aldridge, S., & Rowley, J. (1998). Measuring customer satisfaction in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 6(4), 197–204.

Ali, F., Zhou, Y., Hussain, K., Nair, P. K., & Ragavan, N. A. (2016). Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty? A study of international students in Malaysian public universities. Quality Assurance in Education, 24(1), 70–94.

Alves, H. (2011). The measurement of perceived value in Higher Education: A unidimensional approach. The Service Industries Journal, 31(12), 1943–1960.

Alves, H., & Raposo, M. (2007). Conceptual model of student satisfaction in Higher Education. Total Quality Management, 18(5), 571–588.

Alves, H., & Raposo, M. (2010). The influence of university image on student behaviour. The International Journal of Educational Management, 24(1), 73–85.

AMA: American Marketing Association (2013) Dictionary. http://www.marketingpower.com/_layouts/Dictionary.aspx?source=footer.

Andreassen, T. W., & Lindestad, B. (1998). Customer loyalty and complex services: The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degrees of service expertise. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 9(1), 7–23.

Appleton-Knapp, S. L., & Krentler, K. A. (2006). Measuring student expectations and their effects on satisfaction: The importance of managing student expectations. Journal of Marketing Education, 28, 254–264.

Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. (2011). Trends in Higher Education. Ottawa: The Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.

Astin, A. W. (1999). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518–529.

Athanassopoulos, A. (2000). Customer satisfaction cues to support market segmentation and explain switching behavior. Journal of Business Research, 47(3), 191–207.

Athiyaman, A. (1997). Linking student satisfaction and service quality perceptions: The case of university education. European Journal of Marketing, 31(7), 528–540.

Bailey, R. (2013). Exploring the engagement of lecturers with learning and teaching agendas through a focus on their beliefs about, and experience with, student support. Studies in Higher Education, 38(1), 43–155.

Baumann, C., & Winzar, H. (2016). The role of secondary education in explaining competitiveness. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 36(1), 1–18.

Baumann, C., Hamin, H., & Yang, S. J. (2016). Work ethic formed by pedagogical approach: Evolution of institutional approach to education and competitiveness. Asia Pacific Business Review, 22(3), 1–21.

Beerli Palacio, A., Díaz Meneses, G., & Pérez Pérez, P. J. (2002). The configuration of the university image and its relationship with the satisfaction of students. Journal of Educational Administration, 40(5), 485–505.

Beerli Palacio, A., & Martin, J. D. (2004). Factors influencing destination image. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 657–681.

Bess, J. L., & Shearer, R. E. (1994). College image and finances: are they related to how much students learn. New York: New York University.

Bigné, E., Moliner, M., & Sánchez, J. (2003). Perceived quality and satisfaction in multiservice organizations: The case of Spanish public services. Journal of Services Marketing, 17(4), 420–442.

Bitner, M. J., Booms, B., & Tetreault, M. (1990). The service encounter: diagnosing favourable and unfavourable incidents. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 71–84.

Blázquez Resino, J. J., Chamizo González, J., Cano Montero, E. I., & Gutiérrez Broncano, S. (2013). Calidad de vida universitaria: Identificación de los principales indicadores de satisfacción estudiantil. Revista de Educación, 362(3), 458–484.

Bloemer, J., & Ruyter, K. (1998). On the relationship between store image, store satisfaction and store loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 32(5/6), 499–513.

Borden, V. M. H. (1995). Segmenting student markets with a student satisfaction and priorities survey. Research in Higher Education, 36(1), 73–88.

Brown, R. M., & Mazzarol, T. W. (2009). The importance of institutional image to student satisfaction and loyalty within higher education. Higher Education, 58(1), 81–95.

Brunner, T. A., Stöcklin, M., & Opwis, K. (2008). Satisfaction, image and loyalty: New versus experienced customers. European Journal of Marketing, 42(9/10), 1095–1105.

Bryce, H. (2007). The public’s trust in nonprofit organizations: The role of relationship marketing and management. California Management Review, 49(4), 112–132.

Chen, C. F., & Chen, F. S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35.

Chen, C. F., & Tsai, D. (2007). How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tourism Management, 28(4), 1115–1122.

Chen, C. F., & Tsai, M. H. (2008). Perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty of TV travel product shopping: Involvement as a moderator. Tourism Management, 29(6), 1166–1171.

Cheng, T. M., & Lu, C. C. (2013). Destination image, novelty, hedonics, perceived value, and revisiting behavioral intention for island tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 18(7), 766–783.

Chin, W. W. (1998a). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chin, W. W. (1998b). Issues and opinion on structural equation modelling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), 8–15.

Chin, W.W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (1996). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo Simulation Study and Voice Mail Emotion/Adoption Study. Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Information Systems, Cleveland, Ohio.

Chiu, C. M., Wang, E. T., Fang, Y. H., & Huang, H. Y. (2014). Understanding customers' repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Information Systems Journal, 24(1), 85–114.

Choi, K.-S., Cho, W.-H., Lee, S., Lee, H., & Kim, C. (2004). The relationships among quality, value, satisfaction and behavioural intention in health care provider choice: A South Korean study. Journal of Business Research, 57, 913–921.

Chung, E., & McLarney, C. (2000). The classroom as a service encounter: Suggestions for value creation. Journal of Management Education, 24(4), 484–500.

Clemes, M. D., Cohen, D. A., & Wang, Y. (2013). Understanding Chinese university students' experiences: An empirical analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 25(3), 391–427.

Cronin Jr., J. J., Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioural intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218.

Cronin, J. J., & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. Journal of Marketing, 56(3), 55–68.

Cuthbert, P. F. (1996). Managing Service Quality in HE: Is SERVQUAL the answer? Part 1. Managing Service Quality, 6(2), 11–16.

da Costa, F. R., & Pelissari, A. S. (2016). Factors affecting corporate image from the perspective of distance learning students in public higher education institutions. Tertiary Education and Management, 22(4), 287–299.

Dana, S. W., Brown, F. W., & Dodd, N. G. (2001). Student perception of teaching effectiveness: A preliminary study of the effects of professors’ transformational and contingent reward leadership behaviours. Journal of Business Education, 2, 53–70.

Del Barrio-García, S., & Luque-Martínez, T. (2012). Análisis de ecuaciones estructurales. In T. Luque-Martínez (ed.), Técnicas de análisis de datos en investigación de mercados. Madrid. Ed. Pirámide.

Delaney, A. M. (2001). Assessing undergraduate education from graduating seniors' perspective: Peer institutions provide the context. Tertiary Education and Management, 7(3), 255–276.

DeShields Jr., O. W., Kara, A., & Kaynak, E. (2005). Determinants of business student satisfaction and retention in higher education: Applying Herzberg’s two factor theory. International Journal of Educational Management, 19(2), 128–139.

Dholakia, U. M. (2001). A motivational process model of product involvement and consumer risk perception. European Journal of Marketing, 35(11/12), 1340–1362.

Dib, H., & Alnazer, M. (2013). The impact of service quality on student satisfaction and behavioral consequences in Higher Education services. International Journal of Economy, Management and Social Sciences, 2(6), 285–290.

Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2012). Consistent and asymptotically Normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. http://www.rug.nl/staff/t.k.dijkstra/Dijkstra-Henseler-PLSc-linear.pdf.

Dijkstra, T.K., & Schermelleh-Engel, K. (2013). Consistent partial least squares for nonlinear structural equation models. Psychometrika, in press (available online). http://springerlink.bibliotecabuap.elogim.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11336-013-9370-0

Dlačić, J., Arslanagić, M., Kadić-Maglajlić, S., Marković, S., & Raspor, S. (2014). Exploring perceived service quality, perceived value, and repurchase intention in higher education using structural equation modelling. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 25(1-2), 141–157.

Dodds, W. B. (1991). In search of value: How price and store name information influence buyers’ product perceptions. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 8(2), 15–24.

Douglas, J. A., Douglas, A., McClelland, R. J., & Davies, J. (2015). Understanding student satisfaction and dissatisfaction: An interpretive study in the UK higher education context. Studies in Higher Education, 40(2), 329–349.

Douglas, J., McClelland, R., & Davies, J. (2008). The development of a conceptual model of student satisfaction with their experience in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 16(1), 19–35.

Dowling, G. R. (1986). Managing your corporate image. Industrial Marketing Management, 15(2), 109–115.

Duarte, P. O., Raposo, M. B., & Alves, H. B. (2012). Using a satisfaction index to compare students’ satisfaction during and after higher education service consumption. Tertiary Education and Management, 18(1), 17–40.

Duque, L. C., & Weeks, J. R. (2010). Towards a model and methodology for assessing student learning outcomes and satisfaction. Quality Assurance in Education, 18(2), 84–105.

Eisingerich, A. B., Auh, S., & Merlo, O. (2014). Acta non verba? The role of customer participation and word of mouth in the relationship between service firms’ customer satisfaction and sales performance. Journal of Service Research, 17(1), 40–53.

Elliott, K. M., & Healy, M. A. (2001). Key factors influencing student satisfaction related to recruitment and retention. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 10(4), 1–11.

Elliott, K. M., & Shin, D. (2002). Student Satisfaction: An alternative approach to assessing this important concept. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 24(2), 197–209.

Fakeye, P., & Crompton, J. (1991). Image difference between prospective, first-time and repeat visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. Journal of Travel Research, 30(2), 10–16.

Fares, D., Achour, M., & Kachkar, O. (2013). The impact of service quality, student satisfaction, and university reputation on student loyalty: A case study of International students in IIUM, Malaysia. Information Management and Business Review, 5(12), 584–591.

Flores, W., Chen, J. C. V., & Ross, W. H. (2014). The effect of variations in banner ad, type of product, website context, and language of advertising on Internet users’ attitudes. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 37–47.

Fornell, C., Johnson, D., Anderson, E., Cha, J., & Bryant, B. E. (1996). The American customer satisfaction index: Nature, purpose, and findings. Journal of Marketing, 60(4), 7–18.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fram, E. H. (1982). Maintaining and Enhancing a College or University Image. Rochester: Institute of Technology.

Freeland, R. E., Spenner, K. I., & McCalmon, G. (2015). I gave at the campus exploring student giving and its link to young alumni donations after graduation. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(4), 755–774.

Gefen, D. (2002). Customer loyalty in E-Commerce. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 3(1), 27–51.

Gielnik, M. M., Frese, M., Kahara-Kawuki, A., Katono, I. W., Kyejjusa, S., Ngoma, M., & Oyugi, J. (2015). Action and action-regulation in entrepreneurship: Evaluating a student training for promoting entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 14(1), 69–94.

Greenwald, A., & Leavitt, C. (1984). Audience involvement in advertising: Four levels. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(1), 187–202.

Greenwald, A., & Leavitt, C. (1985). Cognitive theory and audience involvement. In Alwitt & Mitchell (Eds.), Psychological Processes and Advertising Effects. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Grönross, C. (1984). A service quality model and its marketing implications. European Journal of Marketing, 18(4), 36–44.

Grönroos, C. (1989). Defining marketing: a market-oriented approach. European Journal of Marketing, 23(1), 52–60.

Grummon, P. (2012). Trends in Higher Education. USA: Society for College and University Planning.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hannaford, W., Erffmeyer, R., & Tomkovick, C. (2005). Assessing the value of an undergraduate marketing technology course: What do educators think? Marketing Education Review, 15(1), 67–76.

Hartman, D. E., & Schmidt, S. L. (1995). Understanding student/alumni satisfaction from a consumer’s perspective: The effects of institutional performance and program outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 36(2), 197–217.

Harvey, L. (1995). Keeping the customer satisfied: The Student Satisfaction approach. Resource Document. Quality in Higher Education. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=478016

He, H., & Li, Y. (2011). Key service drivers for high-tech service brand equity: The mediating role of overall service quality and perceived value. Journal of Marketing Management, 27, 77–99.

Helgesen, Ø., & Nesset, E. (2007). Images, satisfaction and antecedents: Drivers of student loyalty? A case study of a Norwegian University College. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(1), 38–59.

Hemsley-Brown, J., & Oplatka, I. (2006). Universities in a competitive global marketplace: A systematic review of the literature on higher education marketing. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 19(4), 316–338.

Hemsley-Brown, J., Melewar, T. C., Nguyen, B., & Wilson, E. J. (2016). Exploring brand identity, meaning, image, and reputation (BIMIR) in higher education: A special section. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3019–3022.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Langer, M. F., & Hansen, U. (2001). Modeling and managing student loyalty: An approach based on the concept of relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(2), 331–344.

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20.

Hill, C. J., & Motes, W. H. (1995). Professional versus generic retail services: New insights. Journal of Services Marketing, 9(2), 23–35.

Hodge, P., Wright, S., Barraket, J., Scott, M., Merville, R., & Richardson, S. (2011). Revisiting ‘how we learn’ in academia: Practice-based learning exchanges in three Australian universities. Studies in Higher Education, 36(2), 167–183.

Hu, H.-H., Kandampully, J., & Juwaheer, T. D. (2009). Relationship and impacts of service quality, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and image: An empirical study. The Service Industries Journal, 29(2), 111–125.

Ivy, J. (2001). Higher education institution image: A correspondence analysis approach. International Journal of Educational Management, 15(6/7), 276–282.

Jin, N. P., Lee, S., & Lee, H. (2015). The effect of experience quality on perceived value, satisfaction, image and behavioral intention of water park patrons: New versus repeat visitors. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(1), 82–95.

Johnson, M. D., Gustafsson, A., Andreassen, T. W., Lervik, L., & Cha, J. (2001). The evolution and future of national customer satisfaction index models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 22(2), 217–245.

Johnston, R. (1995). The determinants of service quality: Satisfiers and dissatisfiers. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 6(5), 53–71.

Joseph, M., Yakhou, M., & Stone, G. (2005). An educational institution’s quest for service quality: Customers’ perspective. Quality Assurance in Education, 13(1), 66–82.

Kheiry, B., Rad, B. M., & Asgari, O. (2012). University intellectual image impact on satisfaction and loyalty of students (Tehran selected universities). African Journal of Business Management, 6(37), 10205–10211.

Kim, H., Woo, E., & Uysal, M. (2015). Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tourism Management, 46, 465–476.

Krugman, H. E. (1965). The impact of television advertising: Learning without involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 29(3), 349–356.

Kumar, N., Hubbard, J. D., & Stern, L. W. (1994). The nature and consequences of marketing channel intermediary commitment. Cambridge: Marketing Science Institute.

Kuo, Y. F., Wu, C. M., & Deng, W. J. (2009). The relationships among service quality, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and post-purchase intention in mobile value-added services. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(4), 887–896.

Lai, L. S. L., To, W. M., Lung, J. W. Y., & Lai, T. M. (2012). The perceived value of higher education: The voice of Chinese students. Higher Education, 63(3), 271–287.

Landrum, R., Turrisi, R., & Harless, C. (1998). University image: The benefits of assessment and modeling. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 9(1), 53–68.

Landrum, R. E., Turrisi, R., & Harless, C. (1999). University image: the benefits of assessment and modeling. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 9(1), 53–68.

Laroche, M., Bergeron, J., & Goutaland, C. (2003). How intangibility affects perceived risk: the moderating role of knowledge and involvement. Journal of Services Marketing, 17(2), 122–140.

Laurent, G., & Kapferer, J. N. (1985). Measuring consumer involvement profiles. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(1), 41–53.

LeBlanc, G., & Nguyen, N. (1997). Searching for excellence in business education: An exploratory study of customer impressions of service quality. International Journal of Educational Management, 11(2), 72–79.