Abstract

Relatively little is known about employee perceptions of workplace psychological injuries following sexual and nonsexual harassment. In quasi-military occupational organizations, such as policing, the rate of sexual harassment to workplace injuries from other sources is comparatively high. In an exploratory 5 × 2 between-subjects factorial experimental projection study, 220 New South Wales Police Force officers responded to one of ten experimental vignettes in which sources of psychological injury and the gender of the injured worker were systematically varied. Results revealed an unexpected effect of experience. Employees aged 30 years and older were significantly more likely to anticipate psychological consequences and clinically diagnosable symptoms than their younger counterparts. As hypothesized, a main effect of injury source, but not gender of the target, emerged for the severity of psychological consequences: a physical injury was perceived to produce significantly more severe psychological injuries than sexual harassment in the form of coercion and unwanted sexual attention. Contrary to the hypothesis, participants rated gender-based hostility higher than other types of sexual harassment as a source of severe psychological harm. Participants believed that gender-based hostility requires more professional intervention and predicted more negative workplace consequences than other psychological injuries caused by other workplace events. As hypothesized, women employees were generally viewed as significantly more vulnerable to negative workplace outcomes than men. The police officers who participated in this study considered women as more likely to experience workplace problems following sexual coercion than other types of workplace injury. Physical injuries, gender-based hostility, and sexual coercion were distinguished from nonsexual harassment and unwanted sexual attention as significantly more likely to produce clinically diagnosable injuries, irrespective of target gender. Implications of these findings for research, practice, and legal policy are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Underestimation of Workplace Psychological Injuries

A common phenomenon in the workplace is that the psychological effects and consequences of workplace stressors that are not caused by physical injury are underestimated because they leave no visible or tangible physiological injury. These include injuries following exposure to unreasonable work demands or conditions, workplace bullying and harassment, and workplace discrimination, including sexual harassment. Currently, in France, a major lawsuit is underway against Orange, a French multinational telecommunications corporation with approximately 170,000 employees, formerly known as France Telecom (National Post, 2016). During a period of organizational restructuring in the course of privatization, many senior and career employees were given either unattainable assignments or nothing meaningful to do. Every week, their inboxes were filled with encouragements to seek work elsewhere, and their managers made comments such as ‘You are not still here, are you?’ The lawsuit was prompted by 69 employee suicides in a period of 3 years and 41 attempted suicides (Chabrak, Craig, & Daidj, 2015) attributed to ‘moral harassment’ in the form of insensitivity to and errors in understanding the nature and extent of psychological consequence of workplace harassment (Nyugen & Janselme, 2016).

Work is vitally important for contemporary personal social identity and interaction (Bergstresser, 2006). Disruption in the form of harassment and constructive discharge (e.g. an employee quitting rather than endure harsh working conditions) as was forced on the Telecom workers was profoundly traumatising. These injurious employment practices and the fatal outcomes might have been avoided had the managers and employees been more aware of the consequences of workplace harassment and common symptoms of psychological workplace injuries (Brijnath, Mazza, Singh, Kosny, Rusechaite, & Collie, 2014).

While not all psychological workplace injuries result in tragedies as extreme as employee suicide, this example underscores the need for further research and education on this topic. This article presents the findings of an exploratory empirical study that compared employee perceptions of the psychological consequences of workplace injuries caused by five common types of workplace events with research outcomes documenting their manifestation in physiological symptoms (somatic effects), general psychological symptoms, clinical sequelae, as well as the duration of each of these symptoms.

The Need for Experimental Research on Responses to Psychological Injuries

In the absence of a controlled experiment, it is impossible to know what factors systematically influence employee and management reactions to a particular claim of a workplace psychological injury. Factors that may be influential can include the characteristics and individual differences associated with a particular individual complainant, strategies of his or her legal advisers, the experience, skills and competence of their legal representatives in presenting the claim, or the expectation and reactions of others including the trier of fact. For example, parties with whom the complainant must consult to lodge a claim and seek representation, such as union and legal representatives and equal employment intake officers and investigators, may fail to pursue a legally viable claim if unacquainted with the potential consequences of psychological injuries. Further, if the claim proceeds, finders of fact such as the jury or the judge who cannot readily foresee that psychological injuries may follow injuries caused by nonphysical sources, such as sexual or other types of workplace harassment, may doubt the veracity and genuine nature of injuries by actual claimants in real cases. This, in turn, often exacerbates the injuries and further delays recovery (Elbers, Akkermans, Cuipers, & Bruinvels, 2013; Grant, O’Donnell, Spittall, Creamer, & Studdert, 2013; Wall, Ogloff, & Morrissey, 2007). If so, the full relief available to the victims of these injuries under the law cannot be realised, under-compensation will ensue, and victims will be denied justice (Brijnath et al., 2014; Kendall & Muenchberger, 2009).

Occupational Sectors and the Influence of Exposure to Workplace Stressors

Most of the employees of France Telecom were office workers whose work interactions were with each other and only indirectly with customers. In contrast, workers in certain high-stress professions have a workload that can include extensive direct exposure to interpersonal interactions with members of the public regarding incidents of a traumatic nature or incidents that are high in conflict. Police, paramedics, and firefighters who routinely deal with stressful situations are expected to be more inured to workplace stressors and not to display the same degree of vulnerability as employees who work in less stressful occupational contexts (Brown, 2013). Whether employees who work in high-stress occupations such as policing are more or less sensitive to the psychological consequences of nonphysical workplace injuries is unknown. The present study examined the perceptions of workplace stressors by experienced police officers employed by the New South Wales Police Force, the largest state police force in Australia.

Male-Dominated Quasi-Military Workplaces

Many military and quasi-military professions that were traditionally male-dominated occupational domains, such as the military service (army, navy, marine corps, and air force) and policing, due to that gendered tradition, have a workplace ethos or culture that anticipates that the employees will become ‘one of the boys’ and be less sensitive or vulnerable to workplace stressors than will employees working in other more gender-balanced occupational domains. The male gender-dominance imparts a workplace culture and expectation that stereotypical male stoicism will prevail in the face of workplace stress, rather than stereotypical female responses to workplace stressors, even among female employees (Burke, 2014). To examine the influence of employee gender on the expectations of psychological injuries, the current study compared responses of participants to injuries that targeted both male and female employees.

Gendered Nature of Certain Workplace Causes of Action

Claims for certain types of workplace injuries may be gender neutral, and others may be gender-related. For example, incidents of workplace bullying appear to affect both men and women, although the specific form of the bullying may vary by gender. Physical injuries may also be gender neutral. In contrast, injuries for certain types of workplace discrimination are more clearly gendered, such as sexual harassment, which is typically experienced and claimed more by female than by male employees (Foote & Goodman-Delahunty, 2005). The gendered nature of the underlying liability claim may exert an influence on the perceived nature and extent of any consequential workplace injuries and the validity of the claimed injury (de Haas, Timmerman, & Hoing, 2009).

Male-dominated quasi-military occupational cultures are widely acknowledged to result in a high prevalence of sexual harassment. In policing, for example, this has been recognised as an ongoing national problem in many countries (e.g. Australia: Broderick, 2016; Canada: Mayor, 2015; Macleans, 2016; New Zealand: Brough & Frame, 2004; The Netherlands: de Hass, Timmerman & Hoing, 2009; United Kingdom: Brown, 2013; United States of America: Collins, 2004). In particular, gender-based hostility and sexual coercion are forms of sexual harassment found to be more prevalent in workplaces where members of the workforce of one gender are more dominant than the other. Accordingly, the present study explored the expectations of male and female police officers regarding both sexual and nonsexual workplace stressors that can cause psychological injuries to assess any differences arising from the source of these injuries. We further distinguished between three different types of sexual harassment, namely gender-based hostility, sexual coercion, and unwanted sexual attention.

Legal Context

A series of legislative and common law provisions allow victims of workplace injury to claim compensation from their employers. Most compensation schemes for physical workplace injuries preceded those available for psychological injuries, which were more recently acknowledged as compensable. As a consequence, research on physical injuries and workers’ compensation schemes for various types of physical injuries has dominated the literature. By comparison, research on workplace events that cause psychological injuries has lagged, and less is known about factors that affect the validation of, and compensation for, claims for psychological injuries (Kendall & Muenchberger, 2009). To explore these differences, the present study compared anticipated psychological consequences of a physical injury with those of four types of nonphysical workplace injuries.

Causes and Symptoms of Psychological Injuries

In some workers’ compensation systems, before monetary compensation can be claimed for discrimination injuries sustained on the job, as a preliminary matter, the claimant must prove the employer’s liability for the injury. Other workers’ compensation systems require only that the injury occurred in the scope and course of the employee’s job. The physiological consequences of physical workplace injuries are often immediately apparent, such as a broken leg or arm following a fall or collision. By comparison, psychological injuries are invisible and are not necessarily immediate, so are less likely to be causally associated by observers with the source of the injury in the workplace. The fact that psychological injuries may emerge some weeks or months after the triggering workplace events places causation in question and increases scepticism about the claimed source of the observed injuries. Injury symptoms and consequences such as depression, psychological trauma, and anxiety disorders, even if present, may not be evident to others in the workplace where there is limited interpersonal interaction between a supervisor and employee, who are often not based in the same location or office.

Injured workers may be reluctant to disclose to others, including their immediate co-workers, that they feel distressed, depressed, or anxious. Moreover, not all employees will have close-enough supportive relationships with their co-workers or a workplace culture that enables them to feel comfortable making personal disclosures regarding their emotional vulnerability. In addition, many employees themselves have limited personal insight into the symptoms of psychological injuries such as anxiety, distress, and depression and may not realise that these symptoms have arisen as a consequence of a workplace psychological injury.

Overview of Study

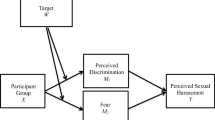

The present study assessed police officers’ expectations about the nature, severity, and duration of psychological injuries arising from physical and nonphysical sources in the workplace. Research participants were presented with one of five workplace vignettes. Three of these vignettes represented different forms of sexual harassment: (1) sexual coercion, (2) unwanted sexual attention, and (3) gender-based workplace hostility. The other two vignettes were not of a sexual nature and involved two types of nonsexual contact, namely (4) nonsexual workplace harassment and (5) physically unsafe workplace conditions. Two versions of each vignette were created: one in which the target was a man (Jason) and the other in which the target was a woman (Anna). In short, a source of workplace stressor (5) by gender of target (2) design was used. All participants were asked to evaluate the vignette with which they were presented by estimating the nature and likelihood of expected problems of the target in their workplace, as well as the target’s physical reactions and psychological responses.

We expected that the perceived responses of targets would differ as a function of the source of the workplace injury. More specifically, we predicted that injuries arising from situations of sexual harassment would be perceived as less severe than physical and nonsexual and non-physical sources of psychological injuries. Moreover, of the three types of sexual harassment, we predicted that psychological injuries caused by sexual coercion would be perceived as more severe than those caused by unwanted sexual attention or gender-based workplace hostility (Espinoza & Cunningham, 2010). Further, we expected that the greater the perceived severity of the injury, the more it would be seen to have an impact on the target’s daily activities and psychological health and to require professional intervention.

We predicted that the consequences of the workplace injuries, irrespective of their source, would be perceived as more severe for female than for male targets. Moreover, we expected that injuries to women from the most stereotypical form of sexual harassment (i.e. sexual coercion) would be perceived as more likely, more severe and enduring than injuries caused by unwanted sexual attention and gender-based workplace hostility.

Method

Participants

A total of 220 New South Wales (NSW) police officers, aged between 21 and 64 years (M = 37.14, SD = 8.12) participated in this study. Two thirds of the participants were between 21 and 30 years of age (66.8 %), and the remaining third were over age 40, with 28.2 % between 41 and 50 years old, and 5 % between 51 and 63 years old. Fifty-five percent of the officers were men and 45 % were women. Approximately one half of the participants (47.7 %, n = 105) reported working up to 9 years for the NSW Police Force, 35.5 % (n = 78) had served in this capacity between 10 and 19 years, 13.6 % (n = 30) between 20 and 29 years, and 2.3 % (n = 5) had served 30 years or more with the NSW Police Force. Most participants (65 %, n = 143) reported having held a supervisory role in NSW Police Force at some point in time, and 45.5 % of the participants were in a supervisory role at the time of data collection.

Materials

Stimulus Materials

Five brief written workplace vignettes specified one of five sources of workplace stress or injury (all five vignettes can be found in the Appendix). Within each vignette, the gender of the target was varied by altering the name of the target (Jason or Anna) and use of male and female pronouns accordingly.

A Sexual coercion vignette described sexual overtures including unwelcome touching of the target by the supervisor, rejection of the advances by the target, followed by a threat by the supervisor to make the target’s promotion very difficult or easy. A second vignette, Unwelcome sexual attention, described unwelcome compliments and touching of the target by a co-worker and persistence by the harasser despite responses by the target that he/she was ‘not interested’. A vignette depicting Gender hostility featured a target who was the sole member of that gender in the department, gender-salient negative comments by a co-worker, and inaction from the supervisor who was aware of the harassing comments. The final two vignettes involved two types of nonsexual workplace stress. In one of the vignettes, nonsexual Co-worker hostility, the target was assigned most of the work, the co-workers declined to help the target, and the manager threatened to ‘write up’ the target for failure to meet deadlines. In a Physical injury vignette, the target asked the supervisor to replace an unstable ladder. After no action was taken, the target subsequently fell from the ladder resulting in physical injuries in the form of a broken leg and bruised hip, requiring 4 weeks in a plaster cast. To avoid confounding results by including injuries arising from duties regarded as inherent policing requirements, such as pursuit of a suspect or discharging a firearm, which might also have elicited inherent gender differences, the physical injury depicted in the vignette was sustained during an activity outside of the scope of inherent requirements of policing. Thus, all injuries were acquired in the course of activities that were not inherent workplace requirements.

Dependent Measures

Using 28 items, the questionnaire measured perceptions of four main types of consequences of the workplace injury described in the vignette on seven-point scales: (a) the severity or gravity of the injuries on the target’s functional capacity (1 = no impact; 7 = significant impact) in terms of (i) the ability to perform the activities of daily life, (ii) general psychological well-being and (iii) the likelihood that the target would need professional help to recover (1 = not at all likely; 7 = extremely likely). Next, the questionnaire assessed (b) the nature of the symptoms anticipated following exposure to one of the five sources of the injury (1 = not at all likely; 7 = extremely likely) and (c) the expected duration of harm (1 = not at all; 2 = 1–7 days; 3 = 8–30 days; 4 = 2–6 months; 5 = 7–12 months; 6 = 1–2 years; 7 = 2 years or more).

Drawing on the research literature (Chan, Lam, Chow, & Cheung, 2008; Fitzgerald, Drasgow, Hulin, Gelfand, & Magley, 1997; Foote & Goodman-Delahunty, 2005) and summaries of meta-analyses on injuries caused by sexual harassment (Goodman-Delahunty & Foote, 2011, 2013), the items probed for potential injury symptoms of four major types: (a) problems experienced in the workplace with co-workers and supervisors (i.e. decreased commitment and productivity, withdrawal, interpersonal difficulties); (b) perceived physiological or somatic responses (i.e. back pain, fatigue, weight loss/gain, headaches, gastrointestinal effects, sleep disturbance, and increased (consumption of drugs/alcohol); (c) psychological distress symptoms that included general reactions (i.e. shame, guilt, relationship problems, fear, worry); and (d) a series of specific diagnosable clinical sequelae (i.e. emotional numbing, worthlessness, depression, and nightmares) that have been observed in sexual harassment victims. This list included three clinical symptoms that were distractor items that are generally unrelated to the injuries depicted in the vignettes (auditory hallucinations, obsessive tidying, and fear of open spaces).

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the ten experimental conditions. They read the workplace vignette describing the potentially stressful event involving the male or female target. After reading the vignette, using seven-point scales, they rated the severity and likelihood that the target would experience different types of consequences of psychological injuries and the expected duration of each.

Analyses

Separate two-way between-subject analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to examine the overall severity of the perceived consequences following exposure to the five different sources of workplace injury and the influence of the source of injury and the target gender on the perceived outcomes in terms of expected problems at work, physical reactions, psychological distress, and clinical symptoms and the expected duration of each type of potential harm or injury.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Preliminary analyses revealed the presence of two univariate and no multivariate outliers. The outliers were deleted from further analyses.

The Influence of Individual Differences on Perceptions of Psychological Harm

No gender differences emerged between the perceptions of male and female participants on any of the dependent measures (p > .05). In contrast, participant age was positively correlated with anticipated psychological and clinical outcomes, indicating that the older participants were, the more likely they were to perceive psychological and potential clinically diagnosable effects of the workplace stressors, as is shown in Table 1.

Perceived Severity of Psychological Injury

The severity or gravity of the perceived psychological injuries was assessed by comparing ratings for each injury source in three ways, in terms of its perceived impact on (a) the activities of daily living of the target, (b) the overall psychological well-being of the target, and (c) the target’s need for professional intervention or assistance to recover from the injuries sustained.

Multivariate ANOVA was conducted to assess the influence of injury source and target gender on the overall perceived severity of the psychological consequences of the injury. These analyses revealed a main effect of injury source on the severity of the psychological injury, F(12, 543) = 4.32, Wilk’s lambda = .786, p < .001, η 2 = .077. No support emerged for the hypothesis regarding the influence of target gender alone or the interaction of injury source and target gender (p > .05).

Each of the severity measures was then considered separately, with the Bonferroni adjusted p value set to .017. The main effect remained significant for the impact on the target’s activities of daily life, F(4, 217) = 5.19, p = .001, η 2 = .091, and psychological well-being, F(4, 217) = 6.40, p < .001, η 2 = .110, but not the likelihood that the target would require professional help, F(4, 217) = 2.58, p = .038, η 2 = .047. As predicted, the perceived impact on the person’s daily activity was significantly higher in the physical injury (M = 5.71, SD = 1.06) than the unwanted sexual attention (M = 5.02, SD = 1.46) and sexual coercion (M = 4.98, SD = 1.55) conditions. Thus, the first hypothesis, that psychological injuries arising from sexual harassment would be perceived as less severe than those from a physical injury, was generally confirmed, except with respect to the impact of gender-based hostility on activities of daily life, which were undifferentiated from those arising from a physical injury. Further, the hypothesis that injuries from nonsexual workplace harassment would exceed those of sexual harassment was not supported. Unexpectedly, the impact of the injury source on daily activities was perceived as significantly more severe from gender hostility (M = 5.80, SD = 1.02) than from sexual coercion (M = 4.98, SD = 1.55).

The perceived impact on the target’s overall psychological well-being was significantly higher from the gender-based hostility (M = 5.55, SD = 1.28) and physical injury (M = 5.45, SD = 1.13) than from unwanted attention (M = 4.50, SD = 1.37) and nonsexual workplace harassment (M = 4.39, SD = 1.75). Figure 1 displays the severity of the perceived impact of the psychological injury by the injury source.

Participants’ ratings of the anticipated need for professional help to recover from the injury revealed that, in general, a moderate need for professional counselling or treatment was expected. The average overall mean score was M = 4.31 (SD = 1.77). Some differences emerged by source of injury: contrary to the hypothesis about the psychological consequences of gender-based hostility versus either a physical injury or sexual coercion, injuries from gender-based hostility was seen to require significantly more professional help to achieve recovery (M = 5.03, SD = 1.63) than were psychological injuries caused by all other types of workplace injury, including sexual coercion.

Problems at Work

Two-way ANOVA revealed a main effect for injury type, F(4, 218) = 7.78, p < .001, η 2 = .130, and target gender, F(1, 218) = 5.81, p = .017, η 2 = .027. These findings contradicted the hypothesis that consequences of a physical and a nonsexual workplace injury would exceed those of gender-based harassment. Specifically, the effect on the target’s problems at work was perceived as significantly more severe from gender-based hostility (M = 6.10, SD = 0.93) than from any other source of injury (physical injury M = 5.35, SD = 1.04; unwanted sexual attention M = 5.07, SD = 1.23; work stress M = 5.01, SD = 1.22; sexual coercion M = 4.87, SD = 1.49). In line with this finding, the second hypothesis regarding target gender was confirmed with respect to the workplace consequences of the injury. Police perceived more that psychologically injured female workers were more vulnerable to severe problems at work (M = 5.41, SD = 1.13) than were their male counterparts (M = 5.10, SD = 1.34). These results are shown in Fig. 2.

Further, the interaction of injury source and gender of target was significant, F(4, 218) = 2.90, p = .023, η 2 = .053. The only source of injury to yield statistically significant gender differences occurred in the sexual coercion vignette, that is, significantly more problems at work were anticipated for the female (M = 5.49, SD = 1.34) than for a similarly situated male target (M = 4.12, SD = 1.31) following this type of sexual harassment. When comparing the source of stressor by target gender, however, no difference was found between the sources of the psychological injury on problems at work for the female target. In other words, every one of the five types of workplace stressors was perceived as equally severe in terms of the consequences anticipated for women in the workplace. However, the perceived severity of the consequences for the male target was dependent on the source of the stress. Police officers perceived that more severe problems at work would arise for the male target following exposure to gender-based hostility (M = 6.10, SD = 0.92) than to nonsexual work harassment (M = 4.95, SD = 1.27), unwanted sexual attention (M = 4.79, SD = 1.28), or sexual coercion (M = 4.12, SD = 1.31). Further, in line with the hypothesized psychological effects of physical versus nonphysical sources of psychological injuries, with respect to the male target, the psychological consequences of a physical injury were perceived as significantly more severe (M = 5.40, SD = 1.10) than those caused by sexual coercion (M = 4.12, SD = 1.31).

When considering the expected duration of problems at work, analyses revealed that these outcomes were replicated, once again yielding a main effect of the source of the injury, F(4, 213) = 8.53, p < .001, η 2 = .144, and of target gender, F(1, 213) = 7.56, p = .007, η 2 = .036. Unexpectedly, problems at work were expected to last longer following gender hostility (M = 5.21, SD = 1.32) than any other type of situation (workplace harassment M = 4.46, SD = 1.33; physical injury M = 4.23, SD = 1.22; sexual coercion M = 3.96, SD = 1.35; unwanted sexual attention M = 3.88, SD = 1.06). Further, as hypothesized, problems at work were expected to last longer for the female (M = 4.51, SD = 1.22) than for the male target (M = 4.17, SD = 1.22). No other comparisons were significant.

Perceived Physiological Reactions and Consequences

Two-way ANOVAs revealed a main effect for injury type on perceived physiological outcomes or reactions of the target, F(4, 217) = 4.98, p = .001, η 2 = .088. Specifically, in line with the first hypothesis, significantly more severe physical reactions were perceived from physical injury (M = 4.46, SD = 1.21) than from unwanted sexual attention (M = 3.55, SD = 1.11). Further, more severe physical reactions were expected from gender-based hostility (M = 4.58, SD = 1.39) than from unwanted sexual attention (M = 3.55, SD = 1.11), and not sexual coercion, as was hypothesized. Contrary to the research hypothesis, on this measure, no differences emerged between male and female targets, F(1, 217) = 1.14, p = .287, η 2 = .005, and the interaction of source of injury and gender was only marginally significant, F(4, 217) = 2.36, p = .055, η 2 = .044. The perceived physical reactions by the type of situation and target gender are presented in Fig. 3.

Further analyses revealed a significant main effect of the source of the injury on the perceived duration of the somatic or physical consequences, F(4, 206) = 8.41, p < .001, η 2 = .147. Contrary to the research hypothesis, the physical reactions were expected to last significantly longer from gender-based hostility (M = 4.42, SD = 1.59) than from sexual coercion (M = 3.38, SD = 1.53), nonsexual workplace harassment (M = 3.37, SD = 1.23), and unwanted sexual attention (M = 2.86, SD = 1.04). In conformity with the research hypothesis, the physical reactions were expected to last longer when caused by a physical injury (M = 3.76, SD = 1.23) than by unwanted sexual attention (M = 2.86, SD = 1.04). No other comparisons were significant.

Perceived Psychological Distress by Source of Workplace Injury

Two-way ANOVA revealed that perceived psychological distress was dependent only on the type of stressor, partially confirming the research hypothesis, F(4, 218) = 7.31, p < .001, η 2 = .123, whereas target gender, F(1, 218) = 0.16, p = .687, η 2 = .001, or the interaction involving target gender and source of stressor, F(4, 218) = 2.18, p = .072, η 2 = .040, was not statistically significant. As expected, post hoc analyses disclosed that psychological distress caused by a physical injury was perceived as more likely than psychological injuries following exposure to nonphysical sources of workplace injuries (M = 4.46, SD = 1.27) such as nonsexual workplace harassment (M = 3.55, SD = 1.26). However, post-hoc analyses revealing that police perceived gender-based hostility in the workplace as significantly more likely to cause psychological distress (M = 4.89, SD = 1.30) than unwanted sexual attention (M = 3.98, SD = 1.25) or nonsexual workplace stress (M = 3.56, SD = 1.26) were unanticipated. These results are presented in Fig. 4.

Similarly, the expected duration of the perceived psychological distress was dependent on the source of the stressor, F(4, 211) = 8.44, p < .001, η 2 = .144, but not on the target gender, F(1, 211) = 1.22, p = .271, η 2 = .006, or the interaction between source of the injury and target gender, F(4, 211) = 1.01, p = .402, η 2 = .020. Contrary to the research hypothesis, but in line with other findings in the study, a comparison of the means revealed that psychological distress was perceived to last longer following gender-based hostility (M = 4.68, SD = 1.56) than sexual coercion (M = 3.75, SD = 1.57), physical injury (M = 3.73, SD = 1.28), work stress (M = 3.27, SD = 1.23), and unwanted sexual attention (M = 3.16, SD = 1.22).

Perceived Clinical Sequelae

The perceived clinical sequelae of workplace injuries were dependent on the injury source, F(4, 217) = 7.63, p < .001, η 2 = .128, but not on the target gender, F(1, 217) = 1.85, p = .175, η 2 = .009, or their interaction, F(4, 217) = 2.66, p = .066, η 2 = .042. These outcomes partially supported the research hypotheses. Specifically, physical injury (M = 5.27, SD = 0.93), gender-based hostility (M = 5.23, SD = 1.07), and sexual coercion (M = 4.94, SD = 1.08) were perceived as significantly more likely to result in more symptoms sufficient to support a clinical diagnosis than were the psychological consequences of nonsexual workplace harassment (M = 4.20, SD = 1.28). Fewer clinical symptoms were perceived as likely following exposure to unwanted sexual attention that that of other forms of sexual harassment (M = 4.77, SD = 1.09), but somewhat more likely than those anticipated following exposure to nonsexual workplace injuries but did not differ significantly from workplace injuries dues to any other source. These results are displayed in Fig. 5.

The expected duration of the clinical outcomes was dependent on type of injury, F(4, 211) = 5.73, p < .001, η 2 = .102, and gender, F(1, 211) = 4.05, p = .045, η 2 = .020, but not their interaction, F(4, 211) = 0.29, p = .885, η 2 = .006. Unexpectedly, clinical sequelae were rated likely to last significantly longer following gender-based hostility (M = 4.73, SD = 1.46) than those arising from nonsexual workplace harassment (M = 3.64, SD = 1.26) and unwanted sexual attention (M = 3.56, SD = 1.16). No difference was found between the expected duration of clinical outcomes following physical injury (M = 4.17, SD = 1.45) and sexual coercion (M = 3.98, SD = 1.32) and gender-based hostility, nonsexual workplace harassment, and unwanted sexual attention. And, as hypothesized, the clinical sequelae were perceived as more likely to persist for a longer time for the female (M = 4.14, SD = 1.38) compared to the male target (M = 3.84, SD = 1.38). In other words, the injury severity to female targets was perceived as more profound when clinical symptoms were considered.

Discussion

This study examined common perceptions of the effects of different types of workplace injuries in a group of employees in a quasi-military occupational sector, the largest state-wide police force in Australia (i.e. the New South Wales Police Force). Employees in this sector are acknowledged to engage in a comparatively high rate of workplace harassment compared to other occupational sectors, including harassment based on both sexual and nonsexual triggers (Morrall, Gore, & Schell, 2016). Thus, the vignettes presented in this study were expected to be familiar to many of the participants. In addition, this group of employees is also known to file a comparatively high rate of claims for workplace injuries (Broderick, 2016; Safe Work Australia, 2013). Thus, the perceptions by this group of employees were expected to reflect their experiences and observations about claims for workplace injuries sustained on the job in the policing sector, despite the fact that the physical injury described was not sustained in the course of pursuing a suspect or engaging in standard policing duties.

Reponses to Different Sources of Psychological Injury

The finding that primacy was accorded to a physical injury as a more significant source of psychological injuries than social factors and treatment in the workplace, whether sexually or nonsexually motivated, is disappointing, but not unexpected. This finding reflects views analogous to those of legal decision-makers who devalue psychological injuries, making it more difficult for plaintiffs to pursue and prevail on these claims (Vallano, 2013).

Conversely, the finding that psychological injuries caused by gender-based hostility were anticipated to exceed those arising from other forms of sexual and nonsexual harassment at work was encouraging. Liability determinations involving claims of gender-based hostility have previously lagged behind those for sexual harassment in the form of quid pro quo claims or claims based on unwanted sexual attention; sexual coercion was regarded as more serious than being subjected to a hostile workplace (Espinoza & Cunningham, 2010; Fitzgerald, Drasgow, & Magley, 1999). The responses of the police participants in his study differ from views of a hostile workplace of two decades ago, when North American men and women (not police officers) were asked to estimate how distressing incidents of gender-based sexual harassment were. They rated them on at par with mildly distressing everyday life experiences, such as being stuck in traffic or failing a test in school (Lees-Haley, Williams, Lees-Haley, Price, & Smith, 1994) and not as a source of psychological injuries. Nonetheless, the inference one might draw from the distinction made by the police participants is that when sexual harassment does not involve hostility and may be construed as flattering to the target because it is assumed to be premised on sexual attraction, the finders of fact may have more difficulty appreciating that a target can be psychologically injured by that conduct.

Responses to the Target Gender

The results confirmed that specific gender-based stereotypes about women as more emotionally fragile and vulnerable to psychological distress than their male counterparts may drive perceived expectations and thus the plausibility of claimed workplace injuries.

These results contrasted with those observed in archival research on Canadian workers’ compensation awards after those laws were modified to encompass claims for psychological injuries. In Quebec, differences were observed in the responses of the justice system to the claimants’ gender, based on the counter-intuitive nature of the claims. Men who claimed psychological distress and injury and thus violated the expected stereotype of male stoicism were awarded higher amounts on average than the matched cases brought by similarly situated female claimants (Lippel, 2005). The explanation provided by the researchers was that the counter-stereotypical nature of the claims enhanced the credibility of the male claimants, whereas the stereotype conformity of similar claims from female counterparts undercut their credibility. In the current study, no such trend emerged. Perhaps because of the male-dominated workplace culture in policing, the psychological injuries to a female worker were rated as more likely, more profound, and more enduring. The surprising finding that gender-based hostility was viewed as a more injurious form of workplace injury than other forms of workplace harassment, sexual and nonsexual, may also be attributable to the particular quasi-military, male-dominated workplace culture in policing.

Implications for Practice

The age difference observed in terms of appreciation of the potential psychological consequences of different workplace events has a number of implications for practice. First, in the workplace, injury claimants are more likely to be older than younger employees, and younger employees may also reflect some intolerance of co-workers or of subordinates who complain of workplace injuries. Younger workers may be insensitive to the psychological consequences of workplace injuries and may not fully understand the causal relationship between these events and ensuing psychological injuries.

A further implication of these results for courts and practitioners is that the consequences of psychological injuries from general workplace bullying and nonsexual harassment may be substantially under-estimated. Employers with the general expectation that the consequences for employees of this type of stressor are less severe may be a factor in the implementation of harsh workplace re-organization strategies, such as those implemented by France Telecom, where no psychologically injurious consequences among employees were anticipated by management, let alone the extremely high rate of suicide among affected employees that ensued. In addition, injuries to targets of workplace sexual harassment in the form of unwanted sexual attention, which can include severe forms of stalking, may be underestimated. This is in part because of stereotypical notions that unwanted sexual attention is merely flattering and is not harmful to the target. Only very recently have scales been developed to assess the potential danger to stalking victims of physical assault, and in some cases, fatal physical attacks, from employees who spurned the advances and attention of others in the workplace (McEwan, Pathe, & Ogloff, 2011; Sheridan & Roberts, 2011).

It is of some concern that observed target gender differences in this study that align with gender-based stereotypes may lead to inequitable treatment of male targets of workplace psychological injuries, at least in the male-dominated occupational sector. Our results indicate that co-workers and managers in the police force do not expect that men who suffer workplace injuries will experience losses in terms of workplace support, meaningful work, or loss of career. Consequently, these injured men may experience ensuing feelings of grief and loss surrounding their identity as a police officer, and in regard to their sense of self-worth and their cognitive appraisal of their masculinity (Wagner, 2016). This may increase their difficulty in reporting and claiming psychological workplace injuries and in achieving just compensation.

Implications for Research and Policy

Future researchers should extend the foregoing findings by assessing the extent to which the perceptions of police are replicated by employees in other occupational sectors. In addition, the impact of perceptions of psychological injuries should be assessed among individuals such as lay jurors, magistrates, and judges who may serve as finders of fact in these cases. Moreover, such research should include determinations of liability, as well as determinations of appropriate compensation after employer liability has been determined for claims of sexual harassment, as well as cases of nonsexual harassment or bullying. The researchers may also want to compare the rate of claims for such injuries by workers under and over the age of 30 years to further explore the generalizability of the age differences observed in the perceptions of psychological versus physical injuries.

At present, the law distinguishes between levels of injury experienced by victims of discrimination and other workplace harassment in a somewhat simplistic fashion, referring to injury severity in two broad categories: (a) the less severe or ‘garden variety’ injuries, on the one hand, which deserve only minimal or limited compensation, and (b) very severe injuries, on the other hand, that are protracted and result in diagnosable psychological or psychiatric conditions (e.g. posttraumatic stress disorder, depression), which typically require expert evidence to support a claim. This dichotomy omits consideration of a very substantial proportion of psychological injuries between those two poles that are neither trivial nor permanently disabling. The findings of this study may be helpful in charting that middle ground, based on the real life experiences of a sample of seasoned police officers who have been exposed to a range of workplace stressors.

The findings that participants perceived psychological injuries as more likely to follow a physical injury (main effect of injury source) over and above nonphysical injury sources provide some basis for concern. In other words, the psychological injuries and symptoms anticipated to be caused by falling off a ladder far exceeded those anticipated to arise from nonphysical workplace sources such as harassment in the form of an unfair workload, uncooperative co-workers, or sexual harassment. This view reflects an outmoded legal standard of causation and remedy that has been rejected as a premise to recover compensation for psychological injuries. It also reflects a degree of scepticism on the part of employees, and thus the community, that such damage claims are meritorious. In light of this finding, the availability of compensatory damages for psychological injuries alone may be insufficient to attain fair and just compensation for such injuries in practice. Put simply, the findings tend to indicate that statutory and common law provisions that permit the recovery of damages for purely psychological injuries, especially those that do not amount to permanent disabilities or clinically diagnosable disorders, may be difficult to enforce. If this is the case, discrimination and harassment victims with such psychological injuries will be sorely undercompensated.

The age-based differences in the perceptions of psychological injuries indicated that further education of younger employees may be needed to familiarise them with the likelihood of psychological injuries in the workplace, their nature, and the common symptoms requiring professional intervention. The age of the police officer was a robust predictor of perceived differences in psychological injuries flowing from the different types of injury sources. Older officers were more likely to anticipate negative consequences from workplace injuries. This finding highlights the importance of maturation in terms of understanding interpersonal interactions at work and the psychological consequences of workplace events.

Limitations of the Study

The assessment in this study of employee perceptions of psychological injuries was preliminary and exploratory. It examined variations in expectations based on different injury sources and differences in the gender of the injured worker. The brief written vignettes included no descriptions of the injuries to guide the participants; thus, the responses are indicative only of projections or expectations in the absence of a further detailed information. These expectations may influence responses of employees, supervisors, managers, and finders of fact but may be modified in light of additional information about a particular injured complainant.

Finally, it should be noted that the findings should be interpreted in light of the study sample. The study recruited active employees of the New South Wales Police Force, and the representativeness of their views to other policing organizations or jury eligible citizens is unclear.

Conclusion

The foregoing study provided evidence of a gap between the findings in the literature on psychological injuries (Winefield, Saebel, & Winefield, 2010) and perceptions by workers of the causes of psychological injuries, their nature and severity, and the consequences of psychological injuries in terms of their impact on the performance of daily activities, psychological well-being, and the need for professional interventions to assist the workers to recover. The study also revealed a series of potential moderators of determinations of liability and compensation for psychological injuries including the source of the injury, the gender of the target, and the plausibility of clinical symptoms assessed by a mental health professional.

References

Bergstresser, S. (2006). Work, identity, and stigma management in an Italian mental health community. Anthology of Work Review, 27(1), 12–20.

Brijnath, B., Mazza, D., Singh, N., Kosny, A., Rusechaite, R., & Collie, A. (2014). Mental health claims management and return to work: qualitative insights from Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 24, 766–776. doi:10.1007/s10926-014-9506-9

Broderick, E. (2016). Cultural change: gender diversity and inclusion in the Australian federal police. Sydney: Elizabeth Broderick & Co.

Brough, P., & Frame, R. (2004). Predicting police job satisfaction and turnover intentions: the role of social support and police organisational variables. New Zealand Journal of Police Psychology, 33(1), 8–16.

Brown, J.M. (ed.) (2013). The future of policing. London: Routledge.

Burke, L. (2014, Nov 13). Female police officer speaks out on sexual harassment in the police force. News.com.au http://www.news.com.au/finance/work/at-work/female-police-officer-speaks-out-on-sexual-harassment-in-the-police-force/news-story/d8dfba48938fbf1d9a6c4dbeb11c0188

Chabrak, N., Craig, R., & Daidj, N. (2015). Financialization and the employee suicide crisis at France Telecom. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2602-8

Chan, D. K.-S., Lam, C. B., Chow, S. Y., & Cheung, S. F. (2008). Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: a meta-analytic review. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 362–376.

Collins, S. C. (2004). Sexual harassment and police discipline: who’s policing the police? Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 27(4), 512–538.

de Haas, S., Timmerman, G., & Höing, M. (2009). Sexual harassment and health among male and female police officers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(4), 390–401. doi:10.1037/a0017046

Elbers, N. A., Akkermans, A. J., Cuipers, P., & Bruinvels, D. J. (2013). Procedural justice and quality of life in compensation process. Injury: International Journal of the Care of the Injured, 44, 1431–1436.

Espinoza, C. B., & Cunningham, G. B. (2010). From observers’ reporting of sexual harassment: the influence of harassment type, organizational culture, and political orientation. Public Organizational Review, 10, 323–337.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: a test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 578–589.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., & Magley, V. J. (1999). Sexual harassment in the armed forces: a test of an integrated model. Military Psychology, 11, 329–343.

Foote, W. E., & Goodman-Delahunty, J. (2005). Evaluating sexual harassment: psychological, social, and legal considerations in forensic evaluations. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Goodman-Delahunty, J., & Foote, W. E. (2011). Evaluation for workplace discrimination and harassment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goodman-Delahunty, J., & Foote, W. E. (2013). Evaluation for harassment and discrimination claims. In R. Roesch & P. A. Zapf (Eds.), Forensic assessments in criminal and civil law: a handbook for lawyers (pp. 175–190). New York: Oxford University Press.

Grant, G. M., O’Donnell, M. L., Spittall, M. J., Creamer, M., & Studdert, D. M. (2013). Relationship between stressfulness of claiming for injury compensation and long-term recovery: a prospective cohort study. Journal of American Medical Association, Psychiatry, 71(4), 446–453.

Kendall, E., & Muenchberger, H. (2009). When systems hurt rather than heal: outcomes following psychological injury at work. In C. A. Marshall, E. Kendall, M. E. Banks, & R. M. S. Gover (Eds.), Disabilities: Insights from across fields and around the world, vol 3: responses: practice, legal, and political frameworks (pp. 145–154). Santa Barbara: Praeger/ABC-CLIO.

Lees-Haley, P. R., Williams, C. W., Lees-Haley, C. E., Price, J. R., & Smith, J. T. (1994). Sexual harassment and emotional distress: a ranking of social sexual behavior. American Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 15(4), 5–25.

Lippel, K. (2005). Le harcelement psychologique au travail: portrait des recours juridiques au Quebec et des decisions rendues par la Commission lesions professionelles. Revue pistes 7(3). http://pistes.revues.org/

Macleans (2016, Feb 16). Public safety minister expresses ‘outrage’ at RCMP’s ‘toxic workplace’ http://www.macleans.ca/news/canada/public-safety-minister-ralph-goodale-expresses-outrage-at-rcmps-toxic-workplace/

Mayor, L. (2015, Nov. 6). Female firefighters face bullying, sexual harassment, fifth estate finds, CBC NEWS. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/female-firefighters-bullying-sexual-harassment-fifth-estate-1.3305509

McEwan, T. E., Pathe, M., & Ogloff, J. R. P. (2011). Advances in stalking assessment. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 29(2), 180–201.

Morrall, A. R., Gore, K.L., & Schell, T. L. (Eds.). (2016). Sexual assault and sexual harassment in the U.S. military, vol 2. Santa Monica, Ca: Rand Corporation.

National Post (2016, July 7). Wave of suicides at France Telecom (now Orange) could send top executives to trial for harassment. http://news.nationalpost.com/news/world/wave-of-suicides-at-france-telecom-now-orange-could-send-top-executives-to-trial-for-harassment

Nguyen, L., & Janselme, K. (2016, July 8, 9, 10). Les victimes de France Telecom ont besoin de justice. L’Humanite, p.1, 4–5.

Safe Work Australia. (2013). The incidence of accepted workers’ compensation claims for mental stress in Australia. Canberra, ACT: Author. http://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/SWA/about/Publications/Documents/769/The-Incidence-Accepted-WC-Claims-Mental-Stress-Australia.pdf

Sheridan, L., & Roberts, K. (2011). Key questions to consider in stalking cases. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 29(2), 255–270.

Vallano, J. P. (2013). Psychological injuries and legal decision making in civil cases: what we know and what we do not know. Psychological Injury and Law, 6, 99–112.

Wagner, M. (2016). The experience of psychological injury and the influence of the workers’ compensation system. Unpublished Masters’ thesis. Charles Sturt University.

Wall, C. L., Ogloff, J. R. P., & Morrissey, S. A. (2007). Psychological consequences of work injury: personality, trauma and psychological distress symptoms of noninjured workers and injured workers returning to, or remaining at work. International Journal of Disability Management Research, 2, 37–46.

Winefield, H. R., Saebel, J. S., & Winefield, A. H. (2010). Employee perceptions of fairness as predictors of workers compensation claims for psychological injury: an Australian case-control study. Stress and Health, 26, 3–12.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was conducted in compliance with international ethical guidelines. Prior to conducting the study, the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia, approved the study. All individual subjects provided informed consent prior to participating in the study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Appendix: Workplace Injury Vignettes (Female Target)

Appendix: Workplace Injury Vignettes (Female Target)

Sexual Coercion (Quid Pro Quo)

On a work-related trip, Anna’s supervisor, Jason, keeps talking about sex and rubbing her shoulders and neck. When she does not respond, he tells Anna to loosen up. Later, Anna asks him about the opportunities in the company for promotion. He says that he is not sure she is ready and tells her, ‘You’ll need to loosen up and be a lot nicer to me before I can recommend you.’ He puts his arms around her waist, adding ‘Remember, I can make your life very easy or very difficult here.’

Unwanted Sexual Attention

Jason asks Anna, his co-worker, if she has been working out a lot. He adds, ‘You’ve got a great body. I’d love to go out with you some time.’ He often brushes up against her. When they are alone in the office, he puts his arms around her and tries to kiss her, but she pushes him away. She tells him she is not interested in dating and asks him not to touch her, but he keeps following her around and touching her ‘accidentally’.

Gender-Based Hostility

Anna is the only female employee in her department. Her co-workers mock her if she makes a mistake. They say, ‘There’s no way you’re gonna get this right, sweetie. It’s a man’s job. You don’t belong here.’ They never include her in their conversations. She overhears them telling crude jokes about her. Some of them jostle her in the hallways. She complains to her supervisor. He says they’re ‘just being friendly’ and tells her to get used to their humour.

Nonsexual Harassment

Anna’s co-workers leave her the most difficult jobs. She often ends up doing other people’s work as well as her own. When another employee quits, Anna is given most of his work, even though she is not trained in those tasks. She asks a co-worker who is always chatting on the phone to help her, but she says ‘Can’t you see I’m busy, I can’t do your work for you.’ The manager says he is going to write her up because she is always falling behind and cannot meet deadlines.

Physical Injury

Anna works in a busy supermarket. She has asked the store manager to replace the ladders, which are not very stable. While she is stacking shelves with heavy bags of dog food, she loses her balance on the ladder and falls heavily onto the concrete floor. She breaks her leg and bruises her hip. Her leg is placed in a cast and she spends 4 weeks on crutches.

For male target: Substituted male name ‘Jason’ for ‘Anna’ and vice versa, in each vignette, and adjusted male and female pronouns as needed.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goodman-Delahunty, J., Schuller, R. & Martschuk, N. Workplace Sexual Harassment in Policing: Perceived Psychological Injuries by Source and Severity. Psychol. Inj. and Law 9, 241–252 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-016-9265-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-016-9265-3