Abstract

In recent years, there has been an increasing recognition of the importance of understanding the educational experiences of immigrant students, particularly in diverse societies like Chile. Immigrant students often encounter unique challenges related to language, culture, and social integration, which can significantly impact their perceptions of school norms, school bonding, experiences of school violence, and overall well-being. However, there is a limited understanding of the specific differences between Chilean students and immigrant students in these domains. This study aims to bridge this gap by examining the differences between Chilean and immigrant students in their perception of school norms, levels of school bonding, experiences of school violence, and well-being. The study used a sample of 2,040 high school students residing in Chile from 20 schools (Mage = 14.9; 49% girls; 11.3% youths of immigrant origin). Results indicated that non-Chilean students exhibited higher levels of behavioral norms and lower levels of bonding. No statistically significant differences were observed for school violence and well-being. Implications for the development of educational policies that promote strategies for the development of a positive school climate are discussed, conceiving the school from the perspective of diverse and inclusive classrooms, which allow for the enrichment of culture and promote the well-being of the entire educational community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Children’s subjective well-being, and in particular, life satisfaction, has shown the relevance of satisfaction with a positive school life. Studies show that positive school experiences, good school performance, and more significant school commitment are associated with high levels of life satisfaction. A positive school climate, including norms valued and accepted by students, and bonding to the school institution. is related to a positive coexistence within the classroom, fewer conflicts due to cultural or ethnic differences, greater tolerance of cultural diversity, and less racial discrimination. However, immigrants are at higher risk of being bullying victims and having less well-being in school. Despite the relevance of these dimensions, few studies have examined in Chile whether there are differences between Chilean and foreign national students regarding their life satisfaction, perception of school norms, school bonding and bullying behaviors. Therefore, our study aimed to examine the differences between Chilean and non-Chilean adolescents considering their self-report all these dimensions which is relevant for adolescents.

1 Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction

The study of subjective well-being (SWB) in children has recently experienced dynamic development (Rees, 2017, 2019) and the value of the importance of considering it from a child’s perspective is increasingly being recognized (Adamson, 2013; Ben-Arieh, 2008a, b). Subjective well-being refers to how individuals evaluate their lives (Campbell et al., 1976). SWB is constituted of three elements. Two of them are the affective processes of positive and negative affect, and the third element concerns the cognitive process of life satisfaction (Diener, 1984). For the purposes of this study, we focus on this last element of well-being: Life satisfaction.

Life satisfaction is the cognitive, global assessment of a person’s behaviors, feelings, and attitudes from their own perspective ranging from positive to negative. One of the best indicators of young people includes happiness, positive functioning, and well-being (Proctor et al., 2009; Suldo & Huebner, 2006). Children’s lives unfold in multiple dimensions: family, peers, neighborhood, friends, school, etc., and each of these influences their perceptions of their own well-being (Ben-Arieh, 2000; Ben-Arieh & George, 2001).

One of the relevant aspects of the study of life satisfaction in children has focused on factors associated with school life (Casas et al., 2014). Life satisfaction is a concept that can contribute to the understanding of school dynamics as determinants of mental health or discomfort (Alfaro et al., 2016a, b; Álvarez et al., 2018; Varela et al., 2017, Bravo-Sanzana et al., 2019a, b, 2020). The literature especially shows the need for more research among children and adolescents across different cultures (Proctor et al., 2009), as there are no periodic and comparable measurements between populations from different socio-cultural contexts (Casas et al., 2013).

1.1 Immigrant Life Satisfaction

The migration experience is complex and has been studied from various perspectives; however, research with a focus on life satisfaction in immigrants is still scarce (Panzeri, 2019). Immigration is one of the most significant stressful events in people’s lives. People who migrate must face multiple stressors, such as loss of social and material support from family or friends, discrimination, underemployment, adaptation to cultural norms and communication barriers, among others. Related research has paid more attention to these already complex aspects of migration than to the study of well-being and happiness. Most studies, mainly in the adult population, tend to show that immigrants often report lower levels of well-being and happiness than natives (Kóczán, 2016; Panzeri, 2019), but less research reports that well-being increases (D’Isanto et al., 2016; Nikolova & Graham, 2015).

The study of well-being in adolescents is essential, as it is a critical period due to the intense physical and psychological changes experienced by adolescents (Gelhaar et al., 2007). It has been shown that life satisfaction tends to decrease during this period compared to childhood, and then gets restored at the onset of young adulthood (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2019; González-Carrasco et al., 2017; Ronen et al., 2016). Although research is scarce, adolescents who also migrate at this time may be more affected by this decline. Such a decline in well-being may be consistent with the other negative effects observed in the acculturation process in immigrants, such as acculturative stress, and mental health problems such as anxiety or depression (Sirin et al., 2013; Turjeman et al., 2008).

In the school context, it is recognized that migration implies a process of psychosocial adjustment for both immigrant students and the receiving society (Salas et al., 2017). Several studies have revealed various barriers that hinder their social and cultural integration (Cerón et al., 2017; Mera-Lemp et al., 2021; Riedemann & Stefoni, 2014; Salas et al., 2017). In the case of Chile, immigration in 2010 accounted for 1.8% of the total population and in 2019 it stood at 7.7%, the highest percentage during the last century (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas [INE], 2018, INE, Departamento de Extranjería y Migración, 2020). A growing increase in the child and adolescent immigrant population has been observed, which in 2018 was 15% of the total number of immigrants (INE 2018, 2020) equivalent to slightly more than 152,000 school-aged children (5 to 19 years old). This growth had already meant a doubling of enrollment in the school system between 2015 and 2017 (Ministerio de Educación [MINEDUC], Centro de Estudios, 2018). As previously observed, this indicates tension in the educational system (Barrios-Valenzuela & Palou-Julián, 2014) mainly focused on public schools that serve the country’s lower-income population who present higher vulnerability indexes (Joiko & Vásquez, 2016). The Chilean Ministry of Education has set out a series of guidelines to manage the integration of immigrant children in schools taking an inclusion approach (Agencia de Calidad de la Educación, Servicio Jesuita de Migración & Consultoría Focus 2019; Superintendencia de Educación, 2016).

Although in Chile research on well-being in immigrants is still scarce, there is some evidence, for example: feeling rooted in a country acts as a positive mediator in the relationship between acculturation stress and psychological well-being of Colombian and Peruvian immigrants residing in Chile (Urzúa et al., 2019). In the school context, it is recognized that migration implies a process of psychosocial adjustment for both migrant students and the receiving society (Salas et al., 2017), several studies have revealed dynamics of discrimination and various barriers that hinder their social and cultural integration for both migrating students (Arellano et al., 2016; Pavez-Soto et al., 2022; Riedemann & Stefoni, 2014), as well as on the attitudes and prejudices of the receiving society (Cerón et al., 2017; Mera-Lemp et al., 2021; Salas et al., 2017; Sirlopú et al., 2015), all these studies account for the difficulties presented to the different actors in the school context.

In Chile, although there are many studies of migrant well-being on adult population (Mera-Lemp et al., 2019, 2020; Silva et al., 2016; Yáñez & Cárdenas, 2010), research on children and youth wellbeing is still scarce, with only a few studies having investigated the topic. Although there are few studies on life satisfaction between Chilean and migrant students, few studies have found no statistically significant difference in average life satisfaction with the Overall Life Satisfaction (OLS) or the dimensions of the Personal Well-Being Index. This result was found with adolescents in Santiago, where the differences were found only in the material condition and the use of time (Céspedes et al., 2020). When life satisfaction was measured with the Student Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS), Céspedes et al. (2021) only found a difference in one item of the scale that states “my life is going well,“ with migrant students scoring higher. However, in the total score of the scale that evaluates satisfaction with life, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups. Another study found that differences in life satisfaction and its domains depended on the group age: in the group of 8–9 years old, immigrants scored higher than non-immigrants in global life satisfaction, while the opposite was found for the group of 10–13 years old (Urzúa et al., 2021). In all age groups, non-immigrants reported higher satisfaction in the domains of family and home and material goods, while migrants had higher satisfaction with school. To these differences, it would be necessary to add the cultural differences that arise in the phenomenon of assimilation in migration, which in the case of migrant children have been studied in the school context since it is this that should welcome and facilitate the integration of these students to culture through a ministerial policy of inclusion. In fact, a qualitative study in the region with the higher population of migrants revealed that inclusion and good treatment depend on the levels of assimilation of migrants, who are also racialized and sexualized, especially girls, in addition to the presence of a discourse of stigmatization of migrant children (Pavez-Soto et al., 2019). Due to sociocultural differences, a deficit is usually attributed to migrant students associated with prejudices from the educational community, difficulty adapting to the norms, and low academic performance (Cerón et al., 2017; Kaluf, 2009).

Although these data are a contribution to the knowledge about the well-being of immigrant children and youth in Chile, there is still a lack of research on adolescent immigrants, their well-being and any interactions with other phenomena found in this context, such as school violence.

1.2 School Violence

Violence against children and adolescents is a global public health, human rights, and social problem (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). Research has unveiled the “biology of violence,“ showing the harmful effects of violent acts on the architecture of the brain during childhood and adolescence (Anda et al., 2010) in addition to its effects in adulthood (Danese & McEwen, 2012).

Violence emerges in various social spaces like schools (Furlong & Morrison, 2000). Akiba et al. (2010) define school violence as any physical or psychological assault, or the threat of assault, by students on other students or teachers at school, including verbal abuse and intimidation for theft, rape, and homicide. Lester et al. (2017) identify expressions of school violence ranging from aggression against school property, interpersonal verbal violence, bullying, up to lethal rampages. According to Devries et al. (2019), in the school context in Latin America and the Caribbean, school violence is widespread in all ages, with physical violence ranging from 17 to 61%. In Chile, school violence was the most common factor associated with a hostile school climate (Trucco & Inostroza, 2017).

Such violence would have consequences for the entire educational community (Castro & Varela, 2013). The literature reports that it negatively affects learning, which is associated with victimization experiences (Bravo-Sanzana et al., 2019a, b, 2020, 2021, Varela et al., 2019, 2021; Gardella et al., 2016). It longitudinally affects different aspects of a person’s life with outcomes associated with mental health and involvement in criminal behaviors (Polanin et al., 2021). From this perspective in a multicultural context, the literature shows evidence first- and second-generation immigrant students reported being victims of bullying more frequently than peers from their home country (Alivernini et al., 2019; Hjern et al., 2013). Likewise, victims of bullying may also experience increased risk behaviors such as self-harm, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation when combined with low social support and connectedness (Eastman et al., 2018). This lack of social support may be exacerbated in multicultural contexts. Thus, there is evidence that immigrant students are victimized more frequently and are more likely to be isolated in the classroom (Alivernini & Manganelli, 2016).

Another form of school violence is manifested in discriminatory behaviors whose purpose or effect nullifies or undermines equal treatment in education (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 1960). This type of violence negatively affects academic engagement for immigrant students with various expressions of stereotypical prejudice (Leaper & Brown, 2014; Leath et al., 2019; Triventi, 2019) and adverse effects on mental health (Puhl & King, 2013). In Chile, one study showed that immigrant children and adolescents have a higher perception of discrimination than non-migrants. These differences are present in all ages, and a significant relationship was observed between perceived discrimination and acculturation stress (Caqueo-Urízar et al., 2019). In addition, a recent study concluded that the presence of discriminatory experiences as an immigrant is a mediating variable of the adaptive process (Segovia, 2021).

Although research on immigration in Chile has increased (Jiménez-Moya et al., 2017; Meeus et al., 2017) there are not enough studies in the school context (Joiko & Vásquez, 2016; Poblete & Galaz, 2017) and more specifically, studies on its relationship with school violence. Even though previous studies highlight the negative consequences of school violence, especially for immigrant children, few studies examined differences among Chilean adolescents. Studying these differences among immigrant and Chilean adolescents is particularly relevant today considering the increasing number of immigrant adolescents and the segregated school system in Chile (Bellei et al., 2019), which may shape a less inclusive school system with a negative school climate.

1.3 School Norms

One important aspect of students’ experience at school is school norms, which are understood as the prescriptions about what is or isn’t allowed in specific spaces (Álvarez-García et al., 2013). Research shows that fair and consistent student discipline, emphasizing compliance with rules, is associated with less negative behavior and school violence (Gottfredson et al., 2005; Kapa & Gimbert, 2018; Weishew & Peng, 1993). In this regard, it is important for the rules to be known by everyone and enforced, without resorting to overly harsh and strict disciplinary practices, as they may potentially trigger even more violent reactions from students (Banzon-Librojo et al., 2017; Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 1985; Heitzman, 1983). Furthermore, it has been observed that, rather than solely disseminating the rules and the associated sanctions for non-compliance, a disciplinary strategy that involves the construction of consensus-based norms with members of the school community is associated with reduced disruptive behavior and lower levels of violence in its various forms within the school environment (Álvarez-García et al., 2013; Pérez, 2007).

Several authors emphasize the advantages of the consensual construction of norms, including facilitating greater knowledge, understanding, and acceptance of the norms by students (DeVries & Zan, 2003; Pérez, 1997). Schimel (2003) suggests that students are more likely to internalize and respect norms that they have participated in creating, as perceiving them as externally imposed may lead them to follow the norms only to avoid punishment, limiting their moral development. According to Barriocanal (2001), democratic strategies for defining norms help reduce conflicts and promote peaceful and satisfactory resolution when they arise. Furthermore, evidence from interventions using this methodology demonstrated positive outcomes, such as improvements in helping and collaborative behaviors, motivation, school engagement, and the organization of the learning environment (Pérez, 2007).

1.4 School Bonding

Social control theory was one of the first to propose that the bonding of individuals to social institutions could inhibit deviant behavior (Hirschi, 1969). Since then, various theoretical frameworks have recognized that bonding to school is a crucial factor that influences students’ development (Catalano et al., 2004; Cernkovich & Giordano, 1992). According to Hirschi (1969), school bonding encompasses emotional connections and positive relationships among students, teachers, and other school members. It also involves aligning personal values with the values promoted by the school and actively engaging in school activities. In contrast, Catalano and Hawkins (1996) argued that involvement is a cause of attachment rather than a dimension of it. They define school bonding as a combination of attachment and commitment to school (Catalano et al., 2004). In their Social Development Model, they emphasize the significance of school bonding as a protective factor that fosters positive outcomes by creating opportunities for positive social interactions and promoting prosocial behaviors.

The Social Development Model (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996) argues that strong social bonds act as a deterrent to behaviors that contradict the beliefs and practices of a social group. Thus, individuals are more likely to display either prosocial or antisocial behavior, depending on the prevailing behaviors, norms, and values upheld by the people or institutions to which they are connected (Catalano et al., 2004). Similarly, Cernkovich and Giordano (1992) suggest that school bonding reduces the likelihood of engaging in delinquent activities. This framework proposes that school bonding comprises two dimensions: one related to attachment and conformity to the overall school experience, and another encompassing teacher-student relationship, peer relationships, and relationships with other members of the school community (Cernkovich & Giordano, 1992; Murray & Greenberg, 2000, 2001). The first dimension is referred to as school attachment and includes the feelings and level of concern that young individuals have towards their educational institution. It encompasses feelings of pride towards the institution, as well as a sense of belonging, security, and comfort within it (Cernkovich & Giordano, 1992).

Consistent with these models, evidence has linked strong school bonding in adolescents to positive outcomes such as psychological well-being, engagement in pro-social behavior, positive interpersonal relationships, and academic achievement (Bryan et al., 2012; Catalano et al., 2004; Eggert et al., 1994; Williams et al., 1999). While weak bonds with school have been associated to risk behaviors such as delinquency, substance abuse, school desertion, break of school norms, and adolescent pregnancy (Cernkovich & Giordano, 1992; Eggert et al., 1994; Hawkins et al., 1997; Henry et al., 2005; Payne et al., 2003; Simons-Morton et al., 1999; Yusek & Solakoglu, 2015). Some argue that this is particularly important for immigrant children and youth, as they face additional challenges (Cernkovich & Giordano, 1992; Peguero & Jiang, 2014). Consequently, they are often exposed to significant risks that can be mitigated through school bonding.

As stated above, the adherence to and understanding of school norms, school bonding, and school violence are significant variables that shape the experiences of children and adolescents in educational settings. These variables may vary between Chilean students and their immigrant peers, leading to distinct experiences within the school environment. By investigating these factors, this study aims to examine the differences in how Chilean students and immigrant students perceive and navigate school norms, experience connections to their schools, and encounter instances of school violence. By examining these differences, we aim to gain insights into the unique challenges faced by immigrant students and contribute to fostering inclusive and supportive educational environments for all students in Chile.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

We used a bi-etapic sample design. First was a convenience sampling design to collect data from different public schools in a single county in Santiago, Chile. After that, it was selected by simple random method, one course (grade) from each level in each school, from 7th to 12th grade. Finally, a sample of 2,040 students that is 49% female with a mean age of 14.9 years, from 20 different public schools in that county in Santiago. Foreigners from countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Haiti, Peru, and Venezuela make up 11.3% of the sample.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Life Satisfaction

We used the measure developed by Huebner (1991) dubbed the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS). This measure has been used in other studies with adolescents in Chile (Alfaro et al., 2016a). It contains five items that evaluate life in a general and context-free manner (Huebner, 2004) with a Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient of 0.79. Examples of items include, “My life is going well”; “My life is just right”; “I have a good life”. Each participant self-reported by scoring on a five-point scale (1 = I don’t know; 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater self-reported life satisfaction.

2.2.2 Behavioral Norms

One of the factors of school coexistence measures students’ self-reports of levels of knowledge and consistency of school norms. This factor was developed by the National Chilean Survey on Violence in School Settings (ENVAE by its Spanish initials, Ministerio del Interior, Subsecretaría Chilena de Prevención del Delito, 2014) which contains six items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Examples of items are, “I understand the rules of my school”, “Students clearly understand what will happen if they don’t follow the rules”, “Students’ opinions are taken into account when the rules of coexistence at my school are modified”. Higher scores indicate more value and recognition of the behavioral norms in the school as self-reported by the students. The scale has high internal reliability (α = 0.78) for the current sample.

2.2.3 Bonding

A second study covariate was also created using the National Chilean Survey on Violence in the School Settings, which measures student self-reported school bonding by asking about feelings of connection and affinity with the school and its members. It uses a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) built with three items addressing the question “How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements about your establishment?” They are, “I feel proud of my school”, “I would like to stay at this establishment next year”, “I feel I am a part of my school”. The scale has high internal reliability (α = 0.85) for the current sample. A higher value on the scale indicates more bonding to the school as self-reported by the students.

2.2.4 Victim of School Violence

We used the ENVAE (Ministerio del Interior, Subsecretaría Chilena de Prevención del Delito, 2014) to examine victim of school violence from peers, developed in 2006 by the Chilean Ministry of Education and Homeland Office. This measure is based on nine items that ask the students about their experiences of being a victim of different types of aggression from peers in the school context over the course of the school year. A few examples of these items are, “During this year 2014, how often have other students assaulted you in your establishment by malicious rumors”, “… physical fights (punching, kicking, hair pulling, etc.)”, … “Teasing or disqualifications [disparagement, negative criticism, put-downs, exclusion, etc..].” This measure uses a five-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = every day), with α = . 89 for the Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient for the current sample. A higher score indicates more self-reports of being a victim of violence at school.

2.2.5 Perpetrator of School Violence

Our last measure was also built using the ENVAE. It has nine items asking students about their experiences of being a perpetrator of different types of aggression against peers in the school context during the school year. Examples of items include, “During this year 2014, how often have you attacked another student in your school in the following ways? … Physical fights (punching, kicking, hair pulling, etc.)”; “Threats or harassment”; “Isolating or excluding another student”. Item response options use a Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = every day) with α = . 90 for the Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient for the current sample. A higher score indicates more self-reports of being a perpetrator of violence at school.

2.3 Procedure

The research design falls within the comparative strategy and corresponds to what Ato et al. (2013) call a retrospective cohort design, since the independent variable that determines the groups to be compared and the dependent variables that are compared were already present at the time the study was conducted.

Data was collected in 7th to 12th grade students’ classrooms during regular classes in November 2015. The students filled out a self-report online questionnaire (Survey Monkey) under the supervision of an external school psychologist especially trained for this purpose in the school computer lab. The study followed ethical protocols by obtaining active consent from the school principal, school family councils, and students with passive consent from their parents. The BLINDED ethical committee approved the study.

2.4 Data Analysis

To evaluate the study hypotheses, an inter-group analysis was done (Chilean vs. non-Chilean students) with the latent means of the variables of life satisfaction, behavioral norms, bonding, victim and perpetrator of school violence. This analysis was carried out in two stages following the recommendations proposed by Thompson and Green (2013).

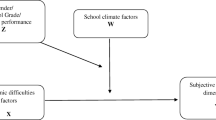

First, the invariance of the measurement between Chilean and non-Chilean students was analyzed for the five scales that measured the studied latent variables using Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MGCFA). The MGCFA necessitated the comparison of a sequence of three models. Model 1: Configural invariance. This model specified the same factor structure for each group, but both thresholds and loadings were freely estimated in both groups. Model 2: Metric invariance. In this model, all loading factors were constrained to be equal across groups, while thresholds were freely estimated with the exception of those thresholds that required constraining to be equal across groups in order to enable identification of the model. Model 3: Scalar invariance. All loading factors and thresholds were constrained to be equal across the two groups. To assess the measurement invariance hypothesis, the sequence adjustment level of the previously described models was compared. A statistically significant reduction in the quality of fit between two models indicates the existence of differences in some parameters between the compared groups. Since each model in the sequence was nested in the previous model, two comparisons were made; Configural vs. Metric and Metric vs. Scalar. To assess the statistical significance of the differences in the quality of the fit, the Difftest option available in the Mplus 8.4 program was used. A non-significant result in these comparisons provides evidence in support of the measurement invariance hypothesis. For the specifications of the partial-metric model, considering the partial invariance presented, we followed the recommendations of Byrne et al. (1989). Once the invariance of the measurement of the scales was established for the two groups being compared, the next step was to evaluate the existence of statistically significant differences in the means of the latent variables between both groups. The measurement model used can be seen in Fig. 1.

Since the items on the scales were answered using ordinal response options, the assumption of multivariate normal distribution is not met, so we proceeded to obtain the matrix of polychoric correlations. The parameters of the models were then estimated using the unweighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (ULSMV) method. The above procedure returns a robust modification of the statistical quality of fit of the analyzed model, and also adequately estimates the parameters and their standard errors (Finney & DiStefano, 2013; Flora & Curran, 2004; Rhemtulla et al., 2012;). Given that the study participants attended different schools, the effect of this grouping (intraclass correlation) when estimating the standard errors was controlled by using an adjustment that was obtained by including the students’ schools as a cluster variable. The goodness of fit of the analyzed models was done based on the following statistics: (a) x2, (b) CFI, (c) TLI (d) RMSEA and its 90% confidence interval. As indicative criteria of a good fit for a model, a non-significant x2 statistic, values of 0.95 or higher for CFI and TLI, and a value less than 0.08 for RMSEA have been proposed (Hu & Bentler, 1999; West et al., 2012). These analyses were conducted using the Mplus 8.4 program.

3 Results

Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics for study variables. Students’ life satisfaction, behavioral norms and school bonding are greater than the average, while victim and perpetrator of school violence are lower. As expected, the self-report of students’ life satisfaction correlates positively with behavioral norms (r = 0.22, p < 0.01) and school bonding (r = 0.23, p < 0.01) perceptions. These variables are positively correlated with one another as well (r = 0.41, p < 0.01). School variables negatively correlated with bullying variables, victim of school violence with life satisfaction (r = − 0.16, p < 0.01), victim of school violence with behavioral norms (r = − 0.12, p < 0.01) and victim of school violence with bonding (r = − 0.18, p < 0.01). Perpetrator of school violence also correlates negatively with school variables, perpetrator of school violence with life satisfaction (r = − 0.09, p < 0.01), perpetrator of school violence with behavioral norms (r = 0.10, p < 0.01), and perpetrator of school violence with bonding (r = − 0.08, p < 0.01). There is a positive correlation between the perpetrator of school violence and victim of school violence variables (r = 0.5, p < 0.01).

3.1 Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To determine to what extent the scales showed measurement invariance between Chilean and non-Chilean students, the adjustments of a sequence of three models were compared, each more restrictive than the previous one in terms of the invariance of its parameters. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, the comparison of the adjustment of the Configural and Metric models (∆χ ^ 2 = 49.844, p = 0.005) led to the rejection of the hypothesis of equality of the loading factor between both groups. The results meant that the loading factor corresponding to items 4 and 5 of the SLSS scale were identified as non-invariant. Therefore, the Metric model was re-specified. This new model (Partial-Metric) specified as invariants all loading factors with the exception of those corresponding to items 4 and 5 of the SLSS scale. The results of the comparison between the Configural and Partial-Metric models presented in Table 2 provided evidence for the hypothesis of partial invariance of the loading factor. Lastly, we proceeded to specify the Scalar model that maintained the partial invariance of the loading factors present in the Partial-Metric model. The invariance of the thresholds was added to this, with the exception of those necessary to make the model identifiable, as well as those corresponding to items 4 and 5 of the SLSS scale. The results of the comparison between the Partial-Metric and Scalar models (∆χ ^ 2 = 102.592, p = 0.12) provided evidence for the hypothesis of partial invariance of the loading factor and of invariance of the thresholds between the groups of Chilean students and non-Chileans. Taken together, these results provided evidence for the hypothesis of partial invariance of the measurement for the set of five analyzed scales.

Once the existence of partial invariance of the measurement between Chilean and non-Chilean students was established, the hypothesis of differences in the means of the five latent variables between both groups was evaluated by comparing the Scalar model with five new models. Each of these new models enabled evaluating whether there were differences in any of the means of the studied latent variables. To do so, the means of the five latent variables were set to zero in the group of Chilean students in each of these new models, while in the group of non-Chilean students only the mean of the latent variable being compared was set to zero with the other four latent means freely estimated. For the Scalar model, the five latent means were set to zero for the group of Chilean students, while all the latent means were freely estimated for the group of non-Chilean students. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 3.

The results indicated that non-Chilean students exhibited statistically higher levels of behavioral norms (∆ [µ_ (Non-Chileans), µ_Chileans] = 0.218), as well as lower levels of bonding (∆ [µ_ (Non-Chileans), µ_Chileans] = -0.512). No statistically significant differences were observed in the means of the remaining three latent variables.

4 Discussion

The results show significant differences for immigrant adolescents concerning: (a) higher adherence to behavioral norms; and (b) lower levels of school connectedness.

Concerning the first result reporting a greater appreciation of school norms understood as an essential school climate factor (Thapa et al., 2013; Wang & Degol, 2016), we suggest that this could be due to a cultural trait of the immigrants in this sample (Dietz, 2012), although this requires further comparative study. Another explanation could be that this is a strategy for adapting to the local norms of the educational system that parents encourage their children to follow as indicated in a recent study (Mondaca et al., 2018). Such an adaptation strategy underlies the evidence that the immigrant population is at risk (Cook et al., 2022; Hjern et al., 2013) and subjected to institutional and interpersonal forms of discrimination (Ayón & Philbin, 2017). Specifically, a poorly inclusive school system that translates into behaviors less tolerant to the culturally different (Jiménez-Moya et al., 2017) despite public policies in education in recent decades. Likewise, this result relieves the school of its role regarding the promotion of a fair and participatory school discipline (Hong et al., 2016; Voight et al., 2015) as a strategy for cultural integration. School community participants (students, parents, teachers, and managers) have higher expectations of the role that teachers should assume than of institutional policies designed to achieve positive sociocultural integration in the educational system (Mondaca et al., 2018).

The finding of lower levels of bonding with the school suggests that students may experience a reduced sense of connection and belonging within the school environment. This is a significant concern as a strong sense of bonding with the school has been associated with positive outcomes such as academic achievement, well-being, and pro-social behaviors. This finding may indicate that the school climate is not fostering an inclusive and supportive atmosphere where students feel valued and connected. This could be due to factors such as limited cultural integration, inadequate support systems, or a lack of opportunities for student participation and involvement. To address these issues, it is crucial to prioritize the establishment of stronger connections, increased participation, and enhanced support from teachers (Catalano et al., 2004; Lewis et al., 2005). Teachers play a vital role in shaping the school climate and creating an environment that promotes positive student experiences. They can facilitate a sense of belonging by fostering positive relationships with students, providing meaningful opportunities for student voice and involvement, and promoting a safe and inclusive learning environment (Caravita et al., 2021; Voight et al., 2015).

These results ask us to view the school as a culturally diverse space, reduce discrimination levels (Hjern et al., 2013) and make progress with studies that help explain intercultural violence. In this regard, recent studies that attempt to answer why young people victimize their immigrant peers have shown that a relevant factor is a lack of moral commitment when participating in victimization (Bayram et al., 2021). Future studies may continue to investigate explanatory factors for the higher levels of violence suffered by the immigrant population despite not seeing those differences in our study.

Under such a perspective, immigrant children and adolescents already shoulder a stressful burden that is characterized by a loss of social and material support, adaptation to cultural norms, and communication barriers to name a few, which affect their well-being and happiness (Casas & González-Carrasco, 2019; González-Carrasco et al., 2017). To the above factors we add the stressful burden of living in a school environment perceived as alien and distant where the school does not represent a space of protection or attachment and is highly segregated (Bellei et al., 2019). One of several potential hypotheses is that the future well-being of these immigrant children and adolescents could be more affected and potentially lead to significant mental health problems (Sirin et al., 2013), entailing additional risks for public health policy.

In conclusion, these results suggest that schools do not function equally as protective contexts for immigrant and non-migrant children and youth, as this population is less linked to school, which may be a protective factor during adolescence (e.g. Bravo-Sanzana et al., 2019a, b, 2020). Although the trend of educational systems worldwide points toward inclusion (Blanco, 2006; Payá, 2010), in Chile, these intentions are yet far from materializing in reality (Castillo, 2016; Martínez et al., 2021; Muñoz-Oyarce, 2021), persisting racial discrimination and stigma towards migrants in the school system (Martínez et al., 2021). Some authors point out that, despite the efforts made in the field of inclusion in the Chilean educational system, some obstacles still exist to turn inclusion into a reality. This begins with, for example, conceptual misconceptions about inclusion held by academic actors, which have led to delays in the implementation of change processes (Gárate, 2019). Furthermore, the lack of public policies for the language immersion of non-Spanish-speaking migrant students hinders inclusion within the Chilean educational system. Thus, the actions to teach the native language to these students depend on the willingness of school professionals (Pavez-Soto et al., 2022). Along the same lines, in a recent review, Martínez et al. (2021) identified a lack of public policy guiding intercultural education in Chilean schools, which leads teachers to intuitively seek to implement initiatives to promote inclusion in the classrooms. These results indicate that schools are not providing the right conditions for immigrant students to develop alongside their native peers to bond with the school. These results suggest that schools are not providing the right conditions for immigrants. As Blanco (2006) points out, different factors influence some students being excluded from the educational system. Still, the results of this research must be interpreted in conjunction with those of other studies, understanding that a single measurement is not enough to capture the complexity of social phenomena. Because of this, it is essential to know which aspects of school experience are important for the healthy development and well-being of youth and children. Studies on life satisfaction in childhood and adolescence can help explain school dynamics, describing whether the interactions that occur in school are determinants of mental health or discomfort (Alfaro et al., 2016).

As mentioned above, the role of teachers is fundamental to promoting inclusive school spaces that meet the needs of all students, with particular attention to minority or more vulnerable groups. However, to strengthen the role of teachers, the school’s institutional policies are essential since these are the framework for teachers’ actions. To achieve this, we consider it necessary to value diversity in the school community because some studies have reported that schools see diversity as an obstacle that interferes with the educational process and stresses the actors of the system rather than as a valuable resource for their pedagogical work (Mora-Olate, 2021; Orellana, 2009). For this reason, it is crucial that at the institutional level, work must be done to make visible the contribution that cultural diversity makes to schools at different levels, such as, for example, the linguistic, cultural, and value contribution (Poblete & Galaz, 2017). In addition, a diverse student body can contribute to the learning of coexistence, offering possibilities for students to practice coexistence skills such as dialogue and conflict resolution, respect for differences, and recognition of others.

As a result, schools should adopt a multiculturalist perspective, which assumes cultural diversity by recognizing and valuing it, and appreciating the positive aspects of the coexistence of different groups within the same nation (Mora-Olate, 2021; Verkuyten, 2006). It is not enough to be aware of the presence of foreign children to declare itself an inclusive school if not to recognize the diversity of its students as a value (Poblete & Galaz, 2017). For Booth and Ainscow (2000), inclusion implies transforming the establishment’s culture and generating new educational policies and practices to provide quality education to each student, regardless of their conditions and backgrounds. Therefore, schools do not only carry out actions whose realization depends on the will of each member of the school team but develop a comprehensive policy that is projected in the long term and involves an intercultural perspective worked in depth (Poblete & Galaz, 2017).

A fundamental aspect of strengthening institutional policies in favor of inclusion is the creation of training programs for teachers and other school staff members since, in Chile, initial teacher training does not include training in competencies to deal with diversity (Mora-Olate, 2021). Training programs should be developed according to the needs of each school since, while some schools that receive a large number of students who speak another language may need training in the linguistic area, others may require, for example, support at the curricular level. It is also crucial for teachers and other school personnel to know and handle information regarding the customs and general culture of the inhabitants of other nations that are received at the school, being aware of the possible differences and cultural clashes that may arise. By knowing and handling other cultures, we can avoid practices of denigration or rejection of specific expressions or ways of behaving of international students based on ignorance about them. However, the experience and knowledge that teachers have accumulated over decades of educating migrant students should also be considered (Ferrada, 2019; Mora-Olate, 2021). This knowledge should be complemented and deepened with new information that allows them to improve their pedagogical practices to promote inclusion.

Finally, an important strategy to include in the policies and daily actions of schools is to seek to increase contact between students from different cultures since contact between different groups decreases prejudice and leads to positive outcomes for the groups involved (Binder et al., 2009; González et al., 2010; Rohmann et al., 2006; Ward & Masgoret, 2006). In particular, good quality intergroup contact, such as that which favors friendly relationships, can benefit inclusive school practices (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006). The school context is undoubtedly an optimal space for introducing this strategy (González et al., 2010), the ideal setting for teaching how to relate respectfully and harmoniously with diversity. In this way, migrant students could strengthen their sense of belonging and connection with the school.

Although this study contributes to the literature on the well-being of the immigrant school-age population, it has some limitations that should be recognized. First, the analyses were conducted with cross-sectional data, meaning the reported direction cannot be determined. Furthermore, the data all come from student self-reports and do not include other key actors in the educational community such as teachers or families, which limited our full understanding of school climate as a collective and multilevel phenomenon Future studies may look into explanatory factors for the greater levels of violence suffered by the immigrant population, taking all this into account Another limitation of the present study is that the data was collected in 2015. More recent data would be useful for understanding if the immigrant population experience in school systems has varied over the years during which immigration has increased. Between 2015 and 2017 only, the immigrant population grew by 67% in Chile (INE, 2018), possibly making interaction with foreigners more common for native youth. It would be useful to study whether this immigrant population growth has meant changes in how Chileans relate to foreigners. Moreover, we can expand this limitation by mentioning our convenience sampling design, which did not include different countries from Latin America, to compare results between them. Therefore, future studies can have another sampling design with larger samples. Lastly, the Chilean Minister of Education developed the measures we used to capture the individual perception of knowledge and adherence to school norms and the perception of school bonding, which can be improved in future studies.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Adamson, P. (2013). Child Well-being in Rich Countries: A comparative overview (Report No. 11). Innocenti Report Card, UNICEF. https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/rc11_eng.pdf. Accessed 9 Dec 2022

Agencia de calidad de la educación, Servicio Jesuita de Migrantes, Estudios y Consultoría Focus (2019). Interculturalidad en la escuela. Orientaciones para la inclusión de estudiantes migrantes. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12365/14363. Accessed 8 Oct 2022

Akiba, M., Shimizu, K., & Zhuang, Y. (2010). Bullies, victims, and teachers in japanese middle schools. Comparative Education Review, 54(3), 369–392. https://doi.org/10.1086/653142

Alfaro, J., Guzmán, J., García, C., Sirlopú, D., Reyes, F., & Varela, J. (2016a). Psychometric properties of the spanish version of the personal wellbeing index-school children (PWI-SC) in chilean school children. Child Indicators Research, 9(3), 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-015-9342-2

Alfaro, J., Guzmán, J., Reyes, F., García, C., Varela, J., & Sirlopú, D. (2016b). Satisfacción global con la vida y satisfacción escolar en estudiantes chilenos. Psykhe, 25(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.25.2.842

Alivernini, F., & Manganelli, S. (2016). The classmates social isolation questionnaire (CSIQ): An initial validation. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(2), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1152174

Alivernini, F., Manganelli, S., Cavicchiolo, E., & Lucidi, F. (2019). Measuring bullying and victimization among immigrant and native primary school students: Evidence from Italy. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 37(2), 226–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282917732890

Álvarez, C. A., Briceño, A. M., Álvarez, K., Abufhele, M., & Delgado, I. (2018). Transcultural adaptation and validation of a satisfaction with life scale for chilean adolescents. Revista Chilena de pediatría, 89(1), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0370-41062018000100051

Álvarez-García, D., Dobarro, A., Rodríguez, C., Núñez, J. C., & Álvarez, L. (2013). Consensus on classroom rules and its relationship with low levels of school violence. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 36(2), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1174/021037013806196229

Anda, R. F., Butchart, A., Felitti, V. J., & Brown, D. W. (2010). Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.015

Arellano, R., Sanhueza, S., García, L., Muñoz, E., & Norambuena, C. (2016). La escuela como espacio privilegiado de integración de los niños inmigrantes. Investigação Qualitativa em Educação, 1, 900–909.

Ato, M., López, J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1038–1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Ayón, C., & Philbin, S. P. (2017). Social Work Research, 41(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svw028

Banzon-Librojo, L. A., Garabiles, M. R., & Alampay, L. P. (2017). Relations between harsh discipline from teachers, perceived teacher support, and bullying victimization among high school students. Journal of Adolescence, 57, 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.03.001

Barriocanal, L. A. (2001). Implicando al alumnado en el establecimiento de normas de clase: normas consensuadas, normas aceptadas. In I. Fernández (Ed.), Guía para la convivencia en el aula (pp. 73–99). CISS PRAXIS.

Barrios-Valenzuela, A., & Palou-Julián, B. (2014). Educación intercultural en Chile: la integración del alumnado extranjero en el sistema escolar. Revista Educación y Educadores, 17(3), 405–426. https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2014.17.3.1

Bayram, S., Özdemir, M., & Boersma, K. (2021). How does adolescents’ openness to diversity change over time? The role of majority-minority friendship, friends’ views, and classroom social context. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 50(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01329-4

Bellei, C., Contreras, M., Canales, M., Orellana, V. (2019). The production of socio-economic segregation in chilean education: School choice, social class and market dynamics. In X. Bonal, X., C. Bellei, C. (Eds.), Understanding school segregation: Patterns, causes and consequences of spatial inequalities in education (pp. 221–240). Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350033542.ch-011

Ben-Arieh, A. (2000). Beyond welfare: Measuring and monitoring the state of children – new trends and domains. Social Indicators Research, 52, 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007009414348

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008a). The child indicators movement: Past, present, and future. Child Indicators Research, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-007-9003-1

Ben-Arieh, A. (2008b). Indicators and indices of children’s well-being: Towards a more policy-oriented perspective. European Journal of Education, 43(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2007.00332.x

Ben-Arieh, A., & George, R. (2001). Beyond the numbers: How do we monitor the state of our children? Children and Youth Services Review, 23(8), 603–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0190-7409(01)00150-5

Binder, J., Zagefka, H., Brown, R., Funke, F., Kessler, T., Mummendey, A., Maquil, A., Demoulin, S., & Leyens, J. P. (2009). Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three european countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(4), 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013470

Blanco, R. (2006). La Equidad y la inclusión social: Uno de los desafíos de la educación y la escuela hoy. Revista Electrónica Iberoamericana Sobre Calidad Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 4(3), 1–15.

Booth, T., & Ainscow, M. (2000). Index for inclusion: Developing learning and participation in schools. Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education (CSIE). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED470516. Accessed 16 Dec 2022

Bravo-Sanzana, M., Miranda-Zapata, E., Huaiquián, C., & Miranda, H. (2019a). Clima social escolar en estudiantes de la Región de la Araucanía, Chile [Social school climate in students of Araucanía distrit, Chile]. Journal of Sport Health Research, 11, 23–40.

Bravo-Sanzana, M., Pavez, M., Salvo, S., & Mieres-Chacaltana, M. (2019b). Autoeficacia, expectativas y violencia escolar como mediadores del aprendizaje en Matemática [Self-efficacy, expectations and school violence as mediators of learning in Mathematics]. Revista Espacios, 40(23), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.48082/espacios

Bravo-Sanzana, M., Salvo-Garrido, S., Miranda-Vargas, H., & Bangdiwala, S. I. (2020). ¿Qué factores de clima social escolar afectan el desempeño de matemática en estudiantes secundarios? Un análisis multinivel [Which school social climate factors affect mathematics performance in secondary school students? A multilevel analysis]. Cultura y Educación, 32(3), 506–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/11356405.2020.1785138

Bravo-Snzana, M., Bangdiwala, S. I., & Miranda, R. (2021). School violence negative effect on student academic performance: A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Injury Control and Safety Promotion, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457300.2021.1994615

Bryan, J., Moore-Thomas, C., Gaenzle, S., Kim, J., Lin, C. H., & Na, G. (2012). The effects of school bonding on high school seniors’ academic achievement. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(4), 467–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2012.00058.x

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthén, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of american life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russell Sage Foundation.

Caqueo-Urízar, A., Flores, J., Irarrázaval, M., Loo, N., Páez, J., & Sepúlveda, G. (2019). Perceived discrimination in migrant schoolchildren in the North of Chile. Psychological Therapy, 37(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082019000200097

Caravita, S., Papotti, N., Gutierrez, E., Thornberg, R., & Valtolina, G. (2021). Contact with migrants and perceived school climate as correlates of bullying toward migrants classmates. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 177, 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20400

Casas, F., Bălţătescu, S., Bertran, I., González, M., & Hatos, A. (2013). School satisfaction among adolescents: Testing different indicators for its measurement and its relationship with overall life satisfaction and subjective well-being in Romania and Spain. Social Indicators Research, 111(3), 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0025-9

Casas, F., & González-Carrasco, M. (2019). Subjective well-being decreasing with age: New research on children over 8. Child Development, 90(2), 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13133

Casas, F., Sarriera, J. C., Alfaro, J., González, M., Figuer, C., Abs da Cruz, D., Bedin, L., Valdenegro, B., & Oyarzún, D. (2014). Satisfacción escolar y bienestar subjetivo en la adolescencia: Poniendo a prueba indicadores para la medición comparativa en Brasil, Chile y España. Suma Psicológica, 21(2), 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0121-4381(14)70009-8

Castillo, D. (2016). Inclusión y procesos de escolarización en estudiantes migrantes que asisten a establecimientos de educación básica [Inclusion and schooling processes in migrant students attending basic education institutions]. (Project No 911463) [Grant]. Departamento de Estudios y Desarrollo, Ministerio de Educación. https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/handle/20.500.12365/18764

Castro, A.,& Varela, J. (2013). Depredador escolar Bully y Cyberbully: salud mental y violencia (Bullyng-Un comportamiento de estos tiempos n°2). Bonum.

Catalano, R., & Hawkins, J. D. (1996). The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In J. D. Hawkins (Ed.), Delinquency and crime: Current theories (pp. 149–197). Cambridge University Press.

Catalano, R. F., Haggerty, K. P., Oesterle, S., Fleming, C. B., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). The importance of bonding to school for healthy development: Findings from the social development research group. Journal of School Health, 74, 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08281.x

Cernkovich, S. A., & Giordano, P. C. (1992). School bonding, race, and delinquency. Criminology, 30(2), 261–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1992.tb01105.x

Cerón, L., Pérez, M., & Poblete, R. (2017). Percepción de docentes en torno a la presencia de niños y niñas migrantes en escuelas de Santiago: Retos y desafíos para la inclusión. Revista Latinoamericana de Educación Inclusiva, 11(2), 233–246. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-73782017000200015

Céspedes, C., Rubio, A., Vera, H., Viña, F., Malo, S., & Navarrete, B. (2021). Satisfacción vital y calidad de vida estudiantil con relación al autoconcepto familiar en el contexto migratorio en Chile. Revista de Investigación en Psicología Social, 7(2), 53–68.

Céspedes, C., Viñas, F., Malo, S., Rubio, A., & Oyanedel, J. C. (2020). Comparación y relación del bienestar subjetivo y satisfacción global con la vida de adolescentes autóctonos e inmigrantes de la Región Metropolitana de Chile. RIEM. Revista Internacional de Estudios Migratorios, 9(2), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.25115/riem.v9i2.3818

Cook, L., Wachter, K., & Rubalcava Hernandez, E. J. (2022). Mi Corazón se Partió en Dos: Transnational Motherhood at the Intersection of Migration and Violence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013404

D’Isanto, F., Fouskas, P., & Verde, M. (2016). Determinants of well-being among legal and illegal immigrants: Evidence from South Italy. Social Indicators Research, 126, 1109–1141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0924-7

Danese, A., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiology & Behavior, 106(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.08.019

Departamento de Extranjería y Migración. (2020). Estimación de personas extranjeras residentes habituales en Chile al 31 de diciembre del 2019. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. https://bit.ly/3rPMpOh. Accessed 12 Dec 2022

DeVries, R., & Zan, B. (2003). When children make rules. Educational Leadership, 61(1), 64–67.

Devries, K., Merrill, K. G., Knight, L., Bott, S., Guedes, A., Butron-Riveros, B., Hege, C., Petzold, M., Peterman, A., Cappa, C., Maxwell, L., Williams, A., Kishor, S., & Abrahams, N. (2019). Violence against children in Latin America and the Caribbean: What do available data reveal about prevalence and perpetrators? Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 43, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.26633/RPSP.2019.66

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542

Dietz, G. (2012). Multiculturalismo, interculturalidad y diversidad en educación. Una aproximación antropológica. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Eastman, M., Foshee, V., Ennett, S., Sotres Alvarez, D., Reyes, H. L. M., Faris, R., & North, K. (2018). Profiles of internalizing and externalizing symptoms associated with bullying victimization. Journal of Adolescence, 65, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.03.007

Eggert, L. L., Thompson, E. A., Herting, J. R., Nicholas, L. J., & Dicker, B. G. (1994). Preventing adolescent drug abuse and high school dropout through an intensive school-based social network development program. American Journal of Health Promotion, 8(3), 202–215. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-8.3.202

Ferrada, D. (2019). La sintonización en la formación inicial docente. Una mirada desde Chile. Revista electrónica de investigación Educativa, 21, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2019.21.e39.2113

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2013). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O Mueller (Eds.), Structural equation modeling. A second course (2nd ed., pp. 439–492). Information Age Publishing.

Flora, D., & Curran, P. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods, 9, 466–491. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466

Furlong, M., & Morrison, G. (2000). The school in school violence: Definitions and facts. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 8(2), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/106342660000800203

Gárate, F. (2019). Inclusión educativa en Chile: Un camino político – histórico con una ruta de empedrados, curvas y colinas [Educational inclusion in Chile: A political-historical road with a path of cobblestones, curves and hills]. Revista Estudios En Educación, 2(2), 143–167.

Gardella, J. H., Tanner-Smith, E. E., & Fisher, B. W. (2016). Academic consequences of multiple victimization and the role of school security measures. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12075

Gelhaar, T., Seiffge-Krenke, I., Borge, A., Cicognani, E., Cunha, M., Loncaric, D., Macek, P., Steinhausen, H., & Metzke, C. W. (2007). Adolescent coping with everyday stressors: A seven-nation study of youth from central, eastern, southern, and northern Europe. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 4(2), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620600831564

González, R., Sirlopú, D., & Kessler, T. (2010). Prejudice among Peruvians and Chileans as a function of identity, intergroup contact, acculturation preferences, and intergroup emotions. Journal of Social Issues, 66(4), 803–824. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01676.x

González-Carrasco, M., Casas, F., Malo, S., Viñas, F., & Dinisman, T. (2017). Changes with age in subjective well-being through the adolescent years: Differences by gender. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18(1), 63–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9717-1

Gottfredson, G. D., & Gottfredson, D. C. (1985). Victimization in schools. Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-4985-3

Gottfredson, G. D., Gottfredson, D. C., Payne, A. A., & Gottfredson, N. C. (2005). School climate predictors of school disorder: Results from a national study of delinquency prevention in schools. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 42(4), 412–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427804271931

Hawkins, J. D., Graham, J. W., Maguin, E., Abbott, R., Hill, K. G., & Catalano, R. F. (1997). Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58(3), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280

Heitzman, A. J. (1983). Discipline and the use of punishment. Education, 104(1), 17–22.

Henry, K. L., Swaim, R. C., & Slater, M. D. (2005). Intraindividual variability of school bonding and adolescents’ beliefs about the effect of substance use on future aspirations. Prevention Science, 6, 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-005-3409-0

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. University of California Press.

Hjern, A., Rajmil, L., Bergström, M., Berlin, M., Gustafsson, P. A., & Modin, B. (2013). Migrant density and well-being–A national school survey of 15-year-olds in Sweden. The European Journal of Public Health, 23(5), 823–828. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckt106

Hong, J. S., Merrin, G. J., Peguero, A. A., Gonzalez-Prendes, A., & Lee, N. Y. (2016). Exploring the social-ecological determinants of physical fighting in U.S. schools: What about youth in immigrant families? Child & Youth Care Forum, 45(2), 279–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-015-9330-1

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Correlates of life satisfaction in children. School Psychology Quarterly, 6(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088805

Huebner, E. S. (2004). Research on assessment of life satisfaction of children and adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66(1/2), 3–33. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SOCI.0000007497.57754.e3

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, INE y Departamento de Extranjería y Migración, DEM (2020). Estimación de personas extranjeras residentes habituales en Chile al 31 de diciembre del 2019. Santiago: Autor. Extraído de https://bit.ly/3rPMpOh. Accessed 12 Oct 2022

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas (2018). Características de la inmigración internacional en Chile. Censo 2017. http://www.censo2017.cl/descargas/inmigracion/181123-documento-migracion.pdf. Accessed 12 Oct 2022

Jiménez-Moya, G., González, R., & De Tezanos-Pinto, P. (2017). Aulas multiculturales: el efecto del contacto intergrupal en la mejora de las actitudes hacia otros grupos. (Nota COES de Política Pública N°13, ISSN: 0719–8795). COES. https://coes.cl/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/N13-Aulas-multiculturales.pdf. Accessed 3 Mar 2023

Joiko, S., & Vásquez, A. (2016). Acceso y elección escolar de familias migrantes en Chile: No tuve problemas porque la escuela es abierta, porque acepta muchas nacionalidades [Access and school choice of migrant families in Chile: I had no problems because the school is open, because it accepts many nationalities]. Calidad en la Educación, 45, 132–173. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-45652016000200005

Kaluf, M. (2009). Niños inmigrantes peruanos en la escuela chilena (Tesis de Magister). Universidad de Chile.

Kapa, R., & Gimbert, B. (2018). Job satisfaction, school rule enforcement, and teacher victimization. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(1), 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2017.1395747

Kóczán, Z. (2016). (Why) are immigrants unhappy? IZA Journal of Migration, 5(3), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40176-016-0052-4

Leaper, C., & Brown, C. S. (2014). Sexism in schools. In L. S. Liben, R. S. Bigler & J.B. Benson (Eds.), The role of gender in educational contexts and outcomes (Vol. 47, pp. 189–223). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acdb.2014.04.001

Leath, S., Mathews, C., Harrison, A., & Chavous, T. (2019). Racial identity, racial discrimination, and classroom engagement outcomes among black girls and boys in predominantly black and predominantly white school districts. American Educational Research Journal, 56(4), 1318–1352. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831218816955

Lester, S., Lawrence, C., & Ward, C. L. (2017). What do we know about preventing school violence? A systematic review of systematic reviews. Psychology Health & Medicine, 22(sup1), 187–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2017.1282616

Lewis, R., Romi, S., Qui, X., & Katz, Y. J. (2005). Teachers’ classroom discipline and student misbehavior in Australia, China and Israel. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21(6), 729–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.008

Martínez, D., Muñoz, W., & Mondaca, C. (2021). Racism, interculturality, and public policies: An analysis of the literature on migration and the school system in Chile, Argentina, and Spain. SAGE Open, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020988526

Meeus, J., Paredes, J., González, R., Brown, R., & Manzi, J. (2017). Racial phenotypically bias in educational expectations for both male and female teenagers from different socioeconomic backgrounds. European Journal of Social Psychology, 47(3), 289–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2247

Mera-Lemp, M. J., Bilbao, M., & Martínez-Zelaya, G. (2020). Discriminación, aculturación y bienestar psicológico en inmigrantes latinoamericanos en Chile. Revista de psicología (Santiago), 29(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-0581.2020.55711

Mera-Lemp, M., Martínez-Zelaya, G., & Bilbao, M. (2021). Adolescentes chilenos ante la inmigración latinoamericana: Perfiles aculturativos, prejuicio, autoeficacia cultural y bienestar [Chilean adolescents facing latin american immigration: Acculturative profiles, prejudice, cultural self-efficacy and well-being]. Revista de Psicología, 39(2), 849–880. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.202102.012

Mera-Lemp, M. J., Ramírez-Vielma, R., Bilbao, M., & Nazar, G. (2019). La discriminación percibida, la empleabilidad y el bienestar psicológico en los inmigrantes latinoamericanos en Chile. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 35(3), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2019a24

Ministerio de Educación de Chile. (2018). Estadísticas de la educación 2017, Publicación diciembre 2018. Centro de Estudios MINEDUC.

Mondaca, C., Muñoz, W., Gajardo, Y., & Gairín, J. (2018). Estrategias y prácticas de inclusión de estudiantes migrantes en las escuelas de Arica y Parinacota, frontera norte de Chile. Estudios atacameños, 57, 181–201. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-10432018005000101

Mora-Olate, M. L. (2021). Escolares migrantes y profesorado: Reflejos de la opresión en la escuela chilena actual. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales Niñez y Juventud, 19(2), 253–272. https://doi.org/10.11600/rlcsnj.19.2.4345

Muñoz-Oyarce, M. F. (2021). Políticas neoliberales y primera infancia: Una revisión desde el enfoque de derechos y la inclusión educativa en Chile [A review from a rights-based approach and educational inclusion in Chile]. Revista Brasilera de Educación Especial, 27, 907–918. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-54702021v27e0039

Murray, C., & Greenberg, M. (2000). Children’s relationship with teachers and bonds with school: An investigation of patterns and correlates in middle childhood. Journal of School Psychology, 38, 423–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00034-0

Murray, C., & Greenberg, M. (2001). Relationships with teachers and bonds with school: Social emotional adjustment correlates for children with and without disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 38, 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(200101)38:13.0.CO;2-C

Nikolova, M., & Graham, C. (2015). In transit: The well-being of migrants from transition and post-transition countries. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 112, 164–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2015.02.003

Orellana, M. (2009). Cultura, ciudadanía y sistema educativo: cuando la escuela adoctrina. LOM.

Panzeri, R. (2019). Bienestar subjetivo de migrantes: La ausencia de la dimensión género. Collectivus: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 6(2), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.15648/Coll.2.2019.3

Pavez-Soto, I., Ortiz-López, J., & Domaica-Barrales, A. (2019). Percepciones de la comunidad educativa sobre estudiantes migrantes en Chile: Trato, diferencias e inclusión escolar. Estudios pedagógicos, 45(3), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052019000300163

Pavez-Soto, I., Ortiz-López, J. E., Villegas-Enoch, P., Grandón-Cánepa, N., Magalhaes, L., Jara, P., & Olguín, C. (2022). Inclusion of migrant children in School in Chile. Open Access Library Journal, 9(11), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4236/oalib.1109391

Payá, A. (2010). Políticas de educación inclusiva en América Latina, Propuestas, realidades y retos de futuro. Revista Educación Inclusiva, 3(2), 125–142. https://revistaeducacioninclusiva.es/index.php/REI/article/view/209. Accessed 12 Dec 2022

Payne, A. A., Gottfredson, D. C., & Gottfredson, G. D. (2003). Schools as communities: The relationships among communal school organization, student bonding, and school disorder. Criminology, 41(3), 749–778. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2003.tb01003.x

Peguero, A. A., & Jiang, X. (2014). Social control across immigrant generations: Adolescent violence at school and examining the immigrant paradox. Journal of Criminal Justice, 42(3), 276–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2014.01.003

Pérez, C. P. (1997). Relaciones interpersonales en el aula y aprendizaje de normas. Bordón: Revista de pedagogía, 49(2), 165–172.

Pérez, C. P. (2007). Efectos de la aplicación de un programa de educación para la convivencia sobre el clima social del aula en un curso de 2º de ESO. Revista de Educación, 343, 503–529.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Poblete, R., & Galaz, C. (2017). Aperturas y cierres para la inclusión educativa de niños/as migrantes en Chile. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 43(3), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07052017000300014

Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., Grotpeter, J. K., Spinney, E., Ingram, K. M., Valido, A., El Sheikh, A., Torgal, C., & Robinson, L. (2021). A meta-analysis of longitudinal partial correlations between school violence and mental health, school performance, and criminal or delinquent acts. Psychological Bulletin, 147(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000314

Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 583–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-008-9110-9

Puhl, R. M., & King, K. M. (2013). Weight discrimination and bullying. Best practice & Research Clinical. Endocrinology & Metabolism, 27(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2012.12.002

Rees, W. (2019). Los mundos de los niños y las niñas [The worlds of boys and girls]. In. G. Tonon, Conocer la vida de niños y niñas desde las palabras de sus protagonistas, (pp. 13–24). Universidad Nacional de Loma de Zamora.

Rees, W. (2017). Children´s views on their lives and well-being: Finding from the children’s worlds Project. Springer International Publishing.

Rhemtulla, M., Brosseau-Liard, P. E., & Savalei, V. (2012). When can categorical variables be treated as continuous? A comparison of robust continuous and categorical SEM estimation methods under suboptimal conditions. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 354–373. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029315

Riedemann, A., & Stefoni, C. (2014). Sobre el racismo, su negación, y las consecuencias para una educación anti-racista en la enseñanza secundaria chilena [On racism, its denial, and the consequences for an anti-racist education in chilean secondary education]. Polis, 14(42), 191–216. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682015000300010

Rohmann, A., Florack, A., & Piontkowski, U. (2006). The role of discordant acculturation attitudes in perceived threat: An analysis of host immigrant attitudes in Germany. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(6), 683–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.06.006

Ronen, T., Hamama, L., Rosenbaum, M., & Mishely-Yarlap, A. (2016). Subjective well-being in adolescence: The role of self-control, social support, age, gender, and familial crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 81–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9585-5

Salas, N., Castillo, D., San Martín, C., Kong, E., Thayer, L. E., & Huepe, D. (2017). Inmigración en la escuela: Caracterización del prejuicio hacia escolares migrantes en Chile. Universitas Psychologica, 16(5), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy16-5.iecp

Schimmel, D. M. (2003). Collaborative rule-making and citizenship education: An antidote to the undemocratic hidden curriculum. American Secondary Education, 31(3), 16–35.

Segovia, P. A. (2021). Proceso de adaptación de estudiantes inmigrantes: Hallazgos en escuelas vulnerables de Santiago de Chile [Adaptation process of immigrant students: Findings in vulnerable schools in Santiago de Chile]. OBETS: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 16(2), 507–522. https://doi.org/10.14198/OBETS2021.16.2.17

Silva, J., Urzúa, A., Caqueo-Urizar, A., Lufin, M., & Irarrazaval, M. (2016). Bienestar psicológico y estrategias de aculturación en inmigrantes afrocolombianos en el norte de Chile. Interciencia, 41(12), 804–811.

Simons-Morton, B. G., Crump, A. D., Haynie, D. L., & Saylor, K. E. (1999). Student–school bonding and adolescent problem behavior. Health Education Research, 14(1), 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/14.1.99

Sirin, S. R., Ryce, P., Gupta, T., & Rogers-Sirin, L. (2013). The role of acculturative stress on mental health symptoms for immigrant adolescents: A longitudinal investigation. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 736–748. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028398