Abstract

Financial capability is an important competence for adolescents, and secondary school is a natural setting in which to deliver financial education courses. Currently, however, little empirical evidence has been published on the effects of in-school financial education on financial capability in adolescents. This pilot study brought together a randomized experimental design, a combination of local and non-local financial education courses, comprehensive measurements, and multi-level structural equation modeling for data analysis to evaluate the outcomes of a financial education project in a representative sample of Hong Kong adolescents. Results demonstrated that our financial intervention made a positive impact on objective financial knowledge and financial self-efficacy but a negative one on financial behaviors. Positive effects on financial self-efficacy were stronger in male adolescents than in females. Our findings represent an important contribution to the literature regarding financial education at the secondary school level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The concept of financial capability, which includes knowledge of financial concepts, financial access, healthy financial habits, financial motivation and confidence, and a positive attitude toward healthy financial behaviors, has been the focus of a great deal of recent research (Despard and Chowa 2014; Ranta and Salmela-Aro 2018; Winstanley et al. 2018; Xiao and O'Neill 2018; Xiao and Porto 2019). In an increasingly complex economic world, financial capability is not just a key competence for adults, but also for children, adolescents, and emerging adults as they transition out of childhood. As commodities available to children and adolescents become increasingly subdivided and customized, parents may be unable to mediate every consumption decision these young people make (Lucey and Cooter 2008; Suiter and Meszaros 2005). Children and adolescents are now expected to intelligently allocate their disposable financial resources and make independent consumption decisions while resisting temptation from media advertisements and peers. Recently, mobile technologies have added another layer to this complex economic landscape, enabling children and adolescents to use mobile devices to complete financial transactions independently (Ng and Nicholas 2018). Although children enjoy advantages over adults in knowledge and use of electronic devices, mobile platforms require users to have basic financial knowledge to interact with these emerging financial technologies (Ratten 2012).

To encourage service innovation and increase liquidity in the financial services market, government and debt suppliers are offering more and more opportunities for older adolescents and emerging adults to negotiate trade-offs between financial risks and gains. However, those uneducated in financial concepts might only be aware of the convenience, opportunities, and benefits of such products, and not their potential risks. Most emerging adults on college campuses currently have use of a credit card. However, due to a lack of basic understanding of how credit works, irresponsible credit behaviors and management are common among college freshmen (Singh et al. 2018). Carrying significant debt, however, can postpone their financial independence and lead them to grow into less financially responsible adults (CYFI 2013). In mainland China, online loans issued by microfinance platforms have exhibited rapid growth over the past five years. These loans target emerging adults and are accompanied by inadequate resources for government supervision, an imperfect social credit system, and immature laws and regulations (Zhang and Yu 2018). Lack of understanding of the fine print for network loans and personal credit can lead to high-risk credit behaviors and decreased financial and general wellbeing (Zhang and Yu 2018). The Hong Kong government offers partial tuition support to secondary school graduates who elect to pursue postsecondary degrees in self-financed programs. Research indicates that the decision to undertake college study depends on an important financial attitudinal variable, consumer risk tolerance, suggesting a trade-off between risks and gains (Heckman and Montalto 2018). Adolescents and families with limited financial resources may make decisions against their best interests even in the presence of financial incentives from the government.

Acknowledging the need to develop strong financial capability in children, adolescents, and emerging adults, financial education programs aimed at improving young people’s financial capabilities have been implemented at different levels of education. Current literature supports different programs depending on whether the recipients are elementary, secondary, or college students. Recent studies have found that younger children learn best by accumulating experiences rather than being taught financial concepts (Batty et al. 2015; Collins and Odders-White 2015; Sherraden et al. 2011), as at this early stage of development, financial issues are difficult to understand without practical simulations. Adolescents in secondary school are reasonable targets for delivering systematic financial education that covers basic financial topics and includes experiential learning components (Amagir et al. 2018). On the basis of mathematical skills developed in elementary school, secondary school adolescents can more easily grasp the math necessary for understanding financial concepts and develop more informed economic thinking (De Bock et al. 2019). High ownership rates of mobile devices in adolescents have integrated mobile access to purchasing into their daily activities (Bowers et al. 2017). Managing money with minimal parental supervision provides adolescents with opportunities to apply the financial concepts learned in class to real-world financial activities including saving, thoughtful consumption, and online transactions with friends (Lopez-Fernandez et al. 2014; Ouma et al. 2017). The college setting, however, has been shown to be more suitable for topic-specific seminars and workshops. These short programs are customized to educate students on specific issues such as financial control, debt management, and smart use of credit cards, in response to different motives and time affordability among college students (Anderson and Card 2015; Peng et al. 2007).

For global practitioners and financial educators who intend to develop or adopt a systematic financial intervention for local secondary students, studies evaluating financial education for young people are urgently needed. The program should cover relevant financial topics and integrate experiential learning devices such as knowledge teaching, simulation games, case analysis, and interactive communication. All components of financial capability, including financial knowledge, behaviors, attitudes, and self-efficacy, are expected to improve after students have taken the full program. Based on a review of 25 studies evaluating financial education at the secondary level worldwide, only five were found to be designed and implemented as strictly randomized experiments (Bruhn et al. 2016; Amagir et al. 2018). This study used a randomized experimental design with a control group to evaluate the effectiveness of a financial education project in Hong Kong and was designed to address the current lack of evidence regarding adolescent financial education and the development of financial education projects.

1 Financial Education in Adolescents

Despite multiple differences, including variations in content and length of financial education, experimental design, interval between completion of program and follow-up assessment, and measurement tools, the majority of studies published over the last decade demonstrate a positive impact of financial education on objective financial knowledge in secondary school students (Asarta et al. 2014; Becchetti et al. 2013; Carlin and Robinson 2012; Lührmann et al. 2015; Hospido et al. 2015). Of interest, when adopting the same Financial Fitness For Life (FFFL) teaching module and FFFL test, and similar quasi-experiments, the effect size of the impact of financial courses on objective financial knowledge (Butt et al. 2008) was much larger than that from other assessments (Harter and Harter 2009). Differences might result from different program lengths, as the former contained 17 lessons, nearly double that of the latter. Notably, although the programs of both Harter and Harter (2010) and Hinojosa et al. (2010) used similar simulated market games and program length, integrating the component of teaching financial concepts into the game resulted in a much stronger impact of the program on investor knowledge in adolescents, despite variations in experimental designs (Amagir et al. 2018).

Results on the influence of financial education on financial behaviors in previous assessments, however, are mixed and tend to show improvements in self-reported financial behavior, but little impact on objectively assessed saving behaviors (Carlin and Robinson 2012; Danes and Brewton 2014; Lührmann et al. 2015; Mandell 2009). A quasi-experiment conducted by Carlin and Robinson (2012) found that after 19 h of financial knowledge education, a sample of U.S. high school students reported they were more willing to delay consumption and clear debt balances, and less willing to finance their consumption with credits. Similarly, self-reported financial behaviors and healthy financial skepticism improved in another sample of U.S. adolescents after a 10-h financial training program, based on the findings from a pre-to-post-evaluation design (Danes and Brewton 2014). Nevertheless, Lührmann et al. (2015) found teaching financial knowledge regarding shopping, planning, and saving seemed to have no effect on whether to save nor specific saving amount in a sample of 636 Germany adolescents aged 13 to 15.

Despite different experiment designs and study programs, most studies have reported positive effects of financial education on self-reported financial attitudes of adolescent students (Lührmann et al. 2015; Mandell 2009; Niederjohn and Schug 2006; Varcoe et al. 2005). One exception was a study on a 30-h FFFL course, which was not found to positively influence financial attitudes in younger U.S. adolescents (Smith et al. 2011).

A review of existing studies assessing financial education in adolescents brings to light three factors that need to be emphasized. First, much of the literature lacks longitudinal observations following the intervention, and the one longitudinal analysis published found no effect of financial education on financial knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes after following a U.S. sample of adolescents for five years. Second, financial self-efficacy is an important attitudinal variable that is rarely assessed. Third, and most important, the number of strictly randomized experiments with a control group is very small; empirical evidence regarding the impact of financial education on short- and long-term development of financial capability in young people is thus extremely limited.

2 Previous Randomized Experiments

Mandell (2009) conducted a randomized experiment on a sample of 1279 junior secondary school students from 10 schools in Bismarck (North Dakota, USA) alongside a control group to examine the effects of a financial education intervention on objective financial knowledge, saving behaviors, and financial attitudes. It is not clear whether the group assignment was performed at the level of class or school. After about one week, 956 students in the experimental group attended the play “Mad About Money” at the National Theatre for Children in addition to undertaking formal classroom training on money basics, saving, and investment, although not credit or debt management. The program incorporated experiential learning components into the live show along with opportunities to practice real-world money management. Post-education evaluations revealed improved objective financial knowledge and attitudes, but no effect on saving behaviors.

Hinojosa et al. (2010) evaluated the influence of “The Stock Market Game,” a national financial education competition for junior high and high schools, on a representative sample of 522 classrooms distributed across more than 40 states in the U.S. Group assignments were distributed at the class level. Students in the experimental group joined a real-time, team-based, virtual investment exercise lasting for 10 or 15 weeks. Afterwards, investment knowledge was assessed in terms of economic concepts, investment strategies, investor research, and calculations, and was found to be significantly improved after the intervention.

Becchetti and Pisani (2012) performed a randomized controlled experiment on 3820 final-year secondary school students in 118 classes in Rome, Milan, and Genova. Selected groups represented three levels in Italy with different reputations for academic performance, and group assignment was by class level. The experimental group received 16 h of lectures over three months, covering economic and financial basics, although whether or not experiential learning was included was not specified. After the intervention, the students’ financial knowledge was assessed using a test composed of 27 multiple-choice questions. Multi-variant, difference-in-difference tests were run at both the student and class levels. Results revealed significant improvement in objective financial knowledge, but the magnitude of change was different in different cities. Adopting a similar sampling framework, group assignment strategy, intervention instrument, measurement tools, and data analysis strategy on a much smaller sample of 944 adolescents, Becchetti et al. (2013) evaluated the impact of this same project on investment attitudes of adolescents and did not find any effect.

Bruhn et al. (2013, 2016) used a large-scale, randomized, controlled trial to measure the causal effects of a high school financial education program on a sample of Brazilian high school students aged between 15 and 17. Group assignment was by school. Schools in both groups were well balanced in terms of regional GDP per capita and other attributes such as number of students, although the study was limited to schools in developed states. Students allocated to the experimental group received between 72 and 144 h of training over three semesters. The course covered basic topics in personal and public finance and contained experiential learning components, such as applying knowledge to family financial issues with participation from parents. Unlike similar interventions, the course appeared over-weighted towards issues relating to public finance and the macro-economy. Evaluations performed after the training, however, showed that the program improved both short- and long-term objective financial knowledge, financial attitudes, and self-reported financial behaviors.

3 Gender Differences

A few previous studies have assessed whether financial education courses had differential effects on male and female adolescents, with consistent results regarding objective financial knowledge. Mandell (2006) found that financial intervention appeared to be more effective in improving objective financial knowledge in female adolescents compared to males. Becchetti et al. (2013) also found that female adolescents showed greater improvement in objective financial knowledge than males. The evaluation of Danes and Haberman (2007) was in agreement, as well, indicating females benefited more from the program and suggesting this was because they were more unfamiliar with financial concepts and understanding than their male counterparts at the outset, and thus benefited more from taking the courses. Comparatively, studies addressing gender differences regarding financial confidence and behaviors were quite limited. Lührmann et al. (2015) indicated that, compared to females, financial education resulted in more improvements in the financial self-efficacy of male adolescents. Lührmann et al. (2015) also studied whether male and female adolescents were influenced differently by the same financial education module in terms of likelihood to save and did not find any significant differences.

4 The Present Study

The small number of studies utilizing randomized, controlled trials necessitates further evaluation of financial education at the secondary school level. None of these five studies comprehensively evaluated all components of financial capability, including knowledge, behaviors, attitudes, and confidence. The rubrics adopted by Mandell (2009) and Hinojosa et al. (2010) did not cover all topics of personal finance. Among the five studies, four were performed only in developed economies, and the financial interventions in all five were designed by local professionals. As not every developing economy is able to shoulder the enormous cost associated with developing such a program, research is needed to assess if a successful financial education from one economy can be implemented with adolescents in another economy.

To overcome the limitations described above, we used an FFFL curriculum, designed and implemented in the U.S. with proven success, to educate Hong Kong adolescents (Butt et al. 2008; Harter and Harter 2009; Smith et al. 2011). We added locally produced Hong Kong teaching materials to the FFFL module and explored a cooperative module of financial education for adolescents. We used the FFFL standardized test to evaluate objective financial knowledge. Evaluation outcomes of our program are important for other countries and regions that plan to implement a financial education project with limited funding using an existing successful program.

Our study followed a randomized experimental design with control and experimental groups assigned by school to avoid any spillover effects, a procedure adopted by Bruhn et al. (2013, 2016), although no other studies we could locate. We comprehensively assessed financial capability by measuring objective financial knowledge, financial behaviors, financial attitudes, and financial self-efficacy. The most recent research indicates that Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) contains useful features for analyzing data generated from experiments such as this one, but thus far, SEM has been rarely used for processing experimental data (Breitsohl 2019). SEM was adopted to evaluate two experimental models in the current study. In the first model, we hypothesized our financial education program would improve objective financial knowledge in adolescents (Hypothesis 1). Financial attitudes and financial self-efficacy are two important attitudinal variables positively associated with behavioral intentions (Serido et al. 2013); thus, in the second model, we hypothesized financial education would have a direct positive effect on financial behaviors, as well as an effect mediated by improvements to financial attitudes and financial self-efficacy, respectively (Hypotheses 2a-2c).

Data on gender differences in the effects of financial education are scarce, so our SEM model not only assessed the average effects of the program but also evaluated differential effects between females and males. We hypothesized that our intervention would be more effective in improving the objective financial knowledge of female adolescents, and improving financial self-efficacy in male adolescents, based on findings from previous studies (Hypotheses 3a-3b). We did not expect any gender-related differences in the intervention’s effect on financial behaviors (Hypothesis 3c).

5 Methods

5.1 Sampling

Secondary schools in Hong Kong were ranked based on academic achievement, reputation, administrative management, and student demographics. To achieve a representative sample, we selected six target schools at five different bands in our network, listed in descending order of rank: one school in Band 1C, two in Band 2A, one in Band 2B, one in Band 2C, and one in Band 3C. One school in Band 2A and one in 2B were randomly selected as control groups, while participants in the other four schools received the financial intervention. The target age for students in the study was 15 years of age, as children aged 12 to 18 are considered adolescents, and 15 is the median age in this range.

5.2 Procedure

Principals from all six schools accepted our invitation to join the study. Formal approval was obtained from both students and parents in all six schools before group assignment. However, one school in Band 2A elected to withdraw from the study, resulting in a final sample of five schools. Four schools in the experimental group were offered financial courses in May of 2017. All five schools allowed us to perform two rounds of comprehensive assessments, a baseline test and follow-up evaluation.

We recruited Form 3 participants (U.S. equivalent Grade 9) from each school because these students were most likely to be around 15 years of age and were not yet under pressure to prepare for the HKDSE, an important examination for college admission. With the help of school teachers, we excluded any students with special educational needs (SEN). All student participants were issued a comprehensive, self-administered questionnaire to complete in the classroom. To ensure data quality, we arranged for a well-trained research assistant to supervise the assessments and respond to any inquiries from students. The FFFL test and other scales originally in English were translated into traditional Chinese, and translations were checked by back-translation. A follow-up assessment was conducted under the same parameters five months after students in the experimental group completed the financial training.

5.3 Financial Education Module

Students from the four schools assigned to the experiment group received ten weekly after-school workshops; each workshop comprised two 45-min sessions with a 10-min break between. The total amount of time spent in the intervention was 15 h over 10 weeks. The module integrated experiential learning components, including lectures, case studies, group discussions, videos, playing games, role-playing, problem solving, and exercises.

We used both the FFFL and The Chin Family financial educational platforms for teaching. The FFFL teaches students to make sensible decisions regarding earning income, spending, saving, borrowing, investing, and managing money over 22 lessons. Each lesson has a theme, such as “How to Really Be a Millionaire,” “Economic Ways of Thinking,” “Why Some Jobs Pay More than Others,” “Banking Basics,” “All About Interest,” and “Scams and Schemes,” among many others. Relevant content adjustments regarding local credit systems and consumer protection laws were made to suit a Hong Kong context.

The Chin Family platform is designed to help individuals in Hong Kong plan and manage their finances through simple and enjoyable learning experiences. It covers life events, financial management, knowledge of financial products, and scams. In life events, financial planning was taught for different life stages, such as starting work, coping with illness or job loss, or raising a pet. Financial management discusses topics related to budgeting, savings, personal banking, debts, and borrowing, as well as financial planning. An animation series teaches financial terms, including inflation, risk diversification, compound interest, and risk and return. Financial products covered include investment devices such as stocks, warrants, funds, bonds, futures and options, insurance products, financial market behavior such as market misconduct, risk management, investor protection, and financial intermediaries including brokers, analysts, and financial advisers.

5.4 Sample

A total of 270 eligible students in five schools took the baseline assessment. The number of students in each school was well balanced. Sixty-seven students in the school in Band 2B were assigned to the control group that did not receive financial education. All other students attended all sessions of the financial intervention. However, eight and three students in the experimental and control groups, respectively, did not complete the follow-up assessment five months after the intervention. After preliminary descriptive analysis of both baseline and follow-up data, we found that answers from seven and five students in the experimental and control groups, respectively, contained outliers. After excluding outliers and dropouts, the finalized sample comprised 247 adolescents, 188 in the experimental group, and 59 in the control group.

In the finalized sample, the mean age of participants was 14.30 (SD = 0.67). Females made up 57.9%. A majority of adolescents came from families where the father and mother lived together. Out of the total sample, 12.4% of families of adolescents were categorized as poor based on the absolute poverty line set by the Hong Kong government. About half of parents had a high school education (n = 115, 46.6%), followed by about a fifth that only completed middle school (n = 51, 20.6%), and around a tenth that had a bachelor’s degree (n = 25, 10.1%). The proportion of fathers with full-time jobs was 90.8%; for mothers, it was 56.1%.

The finalized sample was deemed valid for data analysis, as the only significant difference found regarding the dropouts was that more of them had mothers with a full-time job as compared to remaining participants (χ2(1) = 4.01, p < 0.05). Group assignment was partially successful, although it must be noted that the mean age of participants in the experimental group was significantly lower than that of the control group (t (245) = 2.16, p < 0.05), and the pretest financial attitudes in the experimental group were significantly higher than that of the control group (t (245) = −2.52, p < 0.01).

5.5 Measurement

5.5.1 Objective Financial Knowledge

We evaluated objective financial knowledge in student participants using the FFFL test, a standardized test designed by the U.S. National Council on Economic Education (NCEE) for high school students taking courses in personal finance. Previous studies have validated this rubric for assessing basic financial understanding in high school students (Cameron et al. 2013; Harter and Harter 2009; Walstad and Rebeck 2016). The FFFL comprises 50 multiple choice questions evenly distributed across five themes: economic thinking, earning income, savings, spending and using credit, and money management. The original U.S. version of the test was translated into Chinese and then checked by back-translation by our research team in Hong Kong. The validity of the Chinese adaption has been established in Hong Kong adolescents (Zhu and Chou 2018). Scores for economic thinking, earning income, savings, spending and using credit, and money management in both waves were calculated by adding up scores for their items, respectively.

5.5.2 Financial Behaviors

Financial behaviors were measured by asking participants to indicate on a five-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) the extent to which they engaged in six positive financial behaviors: saving regularly, tracking monthly expenses, spending within a budget, keeping an adequate balance in their bank account, saving for an emergency, and saving for the future (Shim et al. 2010; Xiao et al. 2009). The internal consistencies for pretest and posttest scores were 0.90 and 0.93, respectively.

5.5.3 Financial Attitudes

Financial attitudes were measured by asking students to indicate on a five-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) their views on the same six positive financial behaviors: saving regularly, tracking monthly expenses, spending within a budget, keeping an adequate balance in the bank account, saving for an emergency, and saving for the future (Shim et al. 2010; Xiao et al. 2009). The internal consistencies for pretest and posttest scores were 0.92 and 0.93, respectively.

5.5.4 Financial Self-Efficacy

Financial self-efficacy was measured by inviting students to indicate on the same five-point scale their views about six items (Lown 2011), including “You find it difficult to address financial challenges (reversely coded),” and “You do not have confidence in financial management (reversely coded).” The internal consistencies for pretest and posttest scores were 0.86 and 0.94, respectively.

5.6 Data Analysis

To address the clustering issue, multi-level structural equation modeling was utilized to analyze the data. We performed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with the pretest and the posttest data respectively, and saved the factor scores for main analysis. To test Hypothesis 1 (financial education will positively shape objective financial knowledge), we modeled pretest objective financial knowledge and experiment status as predictors and posttest objective financial knowledge as an outcome variable at the student level. Considering age and pretest financial attitudes varied significantly between experimental and control groups, these were added as additional covariates at the student level. We evaluated the impact of gender on experimental effect by modeling a binary gender variable and the product of gender and group assignment as independent variables. The intercept of the outcome variable was modeled as random. At the school level, the random intercept at the student level was expected to be predicted by pretest objective knowledge at the school level. Due to the limited number of clusters, we only estimated slope at the school level.

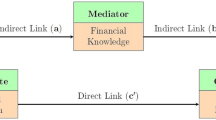

To test Hypotheses 2a, b, and c (financial education will positively influence financial behaviors directly and indirectly through positively shaping financial attitudes and financial self-efficacy), we examined a more complex model at the student level. We input pretest financial attitudes, pretest financial self-efficacy, pretest financial behaviors, and experiment status as predictors, and posttest financial attitudes, posttest financial self-efficacy, and posttest financial behaviors as outcome variables. The model also controlled for age as the covariate. We expected the experiment would improve financial attitudes, financial self-efficacy, and financial behaviors when controlling for baseline scores and age. We also added expected links wherein posttest financial attitudes and posttest financial self-efficacy would positively affect posttest financial behaviors. The influence of gender on the intervention’s effect was tested by modeling a binary gender variable and the product of gender and group assignment as independent variables. The intercept of the outcome variable was modeled as random. At the school level, the random intercept at the student level was expected to be predicted by pretest financial behaviors at the school level. Similarly, because of the small number of clusters, we only estimated slope at the school level.

6 Results

CFA results with the pretest and the posttest data demonstrated good model-data fitness, respectively (χ2 (227, N = 247) = 500.40, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.070; χ2 (227, N = 247) = 572.90, CFI = 0.92, RMSEA = 0.079). Notably, we did not add any residual relations in both CFA models. We saved factor scores in both models for main analysis.

For objective financial knowledge, it was found that differences between males and females were not significant with regard to the intervention. Therefore, the interaction term was removed. Figure 1 reports finalized model results for objective financial knowledge, with good data-model fitness (χ2 (2, N = 247) = 0.21, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.000). At the student level, the financial education intervention significantly increased objective financial knowledge when controlling for baseline scores, age, pretest financial attitudes, and gender (B = 0.40, β = 0.19, p < 0.01). At the school level, different baseline mean scores of objective financial knowledge at different schools in different bands did not significantly affect the intercept of posttest objective financial knowledge at the student level.

For financial attitudes and financial behaviors, it was found that differences between males and females were not significant with regard to the intervention. Therefore, the links from two interaction terms to posttest financial attitudes and financial behaviors were removed. Figure 2 shows the finalized model results for financial behaviors (χ2 (9, N = 247) = 22.49, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.078). Financial education positively and significantly predicted financial self-efficacy (B = 0.38, β = 0.17, p < 0.01), but, unexpectedly, had a negative and significant influence on healthy financial behaviors (B = −0.13, β = −0.07, p < 0.01), when controlling for all pretest scores, age, and gender. Financial education could not significantly predict financial attitudes. Financial intervention could not significantly affect financial behaviors as mediated by either financial attitudes or financial self-efficacy. Notably, males were more positively affected by the intervention with regard to increasing financial self-efficacy (B = 0.17, β = 0.08, p < 0.01). In addition, as adolescents got older, financial self-efficacy significantly decreased (B = −0.11, β = −0.08, p < 0.01). At the school level, we found different mean baseline scores for financial behaviors by school and band positively and significantly predicted the intercept of posttest financial behaviors at the student level (B = 0.21, p < 0.05).

7 Discussion

Financial educators are interested in financial education projects that comprehensively improve financial knowledge, behaviors, self-efficacy, and attitudes in adolescent students. Policymakers require conclusive evidence from randomized experimental trials to decide whether to allocate resources to a candidate financial intervention. Randomized experimental trial evidence in the literature, however, is hard to come by and is undermined by incomplete evaluations of financial capability. This study addressed these limitations by implementing and evaluating a financial education program in Hong Kong adolescents.

Results showed that our financial intervention positively influenced objective financial knowledge, consistent with the evaluation outcomes of most financial education projects implemented at the secondary level (Asarta et al. 2014; Becchetti et al. 2013; Carlin and Robinson 2012; Lührmann et al. 2015; Hospido et al. 2015). As far as we know, this finding is the first to prove the effectiveness of a standardized, international financial education program in a local context. Our program implementation and assessment outcomes could be reference points for other economies eager to promote financial education but lacking locally developed and maintained programs. Selecting an international teaching module, localizing this teaching module, and integrating it into locally produced teaching materials might be a cost-friendly option.

However, assessments of the financial intervention also demonstrated a direct negative effect on healthy financial behaviors and insignificant indirect effect as mediated by either financial attitudes or financial self-efficacy. This should alarm financial educators and policymakers and suggests that the development and implementation of a financial education program suited to adolescents might be more challenging than expected. While financial knowledge as a comprehensive, multi-component knowledge domain needs to be thoroughly demonstrated to students, the types of financial behaviors practiced in adolescence are limited to spending, saving, and budgeting. Thus, the scales used for measurement of behaviors only included six healthy financial behaviors related to spending, saving, and budgeting, although our financial course thoroughly covered economic ways of thinking, earning income, savings, credit management, insurance, and investment. Parents are very likely to advise students to follow their norms and perform these six widely accepted healthy financial behaviors, rather than explain the importance of these financial habits on personal financial planning. The comprehensive financial knowledge delivered to adolescents in this intervention is likely to develop critical thinking in regard to these six financial behaviors, and prior beliefs and habits based on following parental financial norms without an accompanying cognitive foundation might have been shaken. This theory could explain our finding of a negative effect of the financial intervention on behaviors.

Findings did show a positive impact of the financial intervention on financial self-efficacy, but no significant impact on financial attitudes. Similar with items measuring financial behaviors, those measuring financial attitudes included same six healthy financial habits. Critical thinking ability developed in the financial course will not simply increase favorable feeling of adolescents towards them, but will only make them more care about financial world behind them. In comparison, items assessing financial self-efficacy did not clearly define the difference between healthy and unhealthy financial behaviors, but incorporated psychological status, such as satisfaction and confidence in personal finance decisions. The financial project exposes adolescents to a complicated financial world that is very different from the simple financial guidelines taught by parents, and such exposure might influence psychological status. Financial education might have the unanticipated effect of scaring adolescents, making them lose confidence or become confused about financial decision making. Alternatively, financial education might help them reflect on their personal financial experiences and encourage them to make independent and confident decisions. Overall, our findings support the second situation, suggesting our program was successful in improving adolescent financial capability.

Notably, results indicated that the positive effect of our program was stronger for male adolescents than for females, in terms of improving financial self-efficacy, recapitulating the findings of Lührmann et al. (2015). Future programs may consider incorporating more practical components simulating the real financial world and encourage enhanced participation by females. Female students may be better able to establish confidence through practical experience, which could counteract the stronger influence of the program on males in improving financial self-efficacy found in this study. We expect that the design and implementation of this program will allow male and female adolescents to learn equally from training opportunities.

7.1 Limitations

Although the findings of this study address important gaps in the financial education field, several issues should be noted when interpreting results. First, the number of clusters at the school level was limited, and the standard error of the estimated parameters at the school level might not be trustworthy. Second, the number of schools in the experimental and control groups were not balanced, an issue that should be addressed in future evaluations. Therefore, this study can only be considered as a pilot study. Third, our program did not invite parents to cooperate in the training process. Inviting parents from the experimental group to join the intervention might enhance the intervention’s effects. Fourth, one should not necessarily conclude that our financial education intervention had a long-term negative effect on financial behaviors, as it might take time for students to fully internalize the knowledge. With both knowledge and lessons learned from financial experience, they can be provided with the tools necessary to engage in healthy financial behaviors and develop healthy personal habits.

References

Amagir, A., Groot, W., Maassen van den Brink, H., & Wilschut, A. (2018). A review of financial-literacy education programs for children and adolescents. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education, 17(1), 56–80.

Anderson, C., & Card, K. (2015). Effective practices of financial education for college students: students' perceptions of credit card use and financial responsibility. College Student Journal, 49(2), 271–279.

Asarta, C. J., Hill, A. T., & Meszaros, B. T. (2014). The features and effectiveness of the keys to financial success curriculum. International Review of Economics Education, 16, 39–50.

Batty, M., Collins, J. M., & Odders-White, E. (2015). Experimental evidence on the effects of financial education on elementary school students' knowledge, behavior, and attitudes. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(1), 69–96.

Becchetti L. & Pisani, F. (2012). Financial education on secondary school students: The randomized experiment revisited (AICCON Working Papers No. 98). Retrieved from: https://www.aiccon.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/WP-98.pdf. Accessed 1st March 2019

Becchetti, L., Caiazza, S., & Coviello, D. (2013). Financial education and investment attitudes in high schools: Evidence from a randomized experiment. Applied Financial Economics, 23(10), 817–836.

Bowers, J., Reaves, B., Sherman, I. N., Traynor, P., & Butler, K. (2017). Regulators, mount up! Analysis of privacy policies for mobile money services. In Thirteenth symposium on usable privacy and security (pp. 97–114). Berkeley, California: The USENIX Association.

Breitsohl, H. (2019). Beyond ANOVA: An introduction to structural equation models for experimental designs. Organizational Research Methods, 22(3), 649–677.

Bruhn, M., de Souza Leão, L., Legovini, A., Marchetti, R., & Zia, B. (2013). The impact of high school financial education: Experimental evidence from Brazil (World Bank policy research working paper no. 6723). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Bruhn, M., Leão, L. D. S., Legovini, A., Marchetti, R., & Zia, B. (2016). The impact of high school financial education: Evidence from a large-scale evaluation in Brazil. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8(4), 256–295.

Butt, N. M., Haessler, S. J., & Schug, M. C. (2008). An incentives-based approach to implementing financial fitness for life in the Milwaukee public schools. Journal of Private Enterprise, 24(1), 165–173.

Cameron, M. P., Calderwood, R., Cox, A., Lim, S., & Yamaoka, M. (2013). Factors associated with financial literacy among high school students. (working paper in economics no. 13/05). Waikato, New Zealand: Department of Economics, University of Waikato.

Carlin, B. I., & Robinson, D. T. (2012). What does financial literacy training teach us? The Journal of Economic Education, 43(3), 235–247.

Collins, J. M., & Odders-White, E. (2015). A framework for developing and testing financial capability education programs targeted to elementary schools. The Journal of Economic Education, 46(1), 105–120.

CYFI. (2013). Research evidence on the CYFI model of children and youth as economic citizens. CSD Research Review No.13-04. Retrieved from: http://www.bu.edu/bucflp/files/2014/06/CYFI-Research-Brief-Research-Evidence-on-the-child-and-youth-finance-model-of-economic-citizenship-2.pdf. Accessed 5th March 2019

Danes, S. M., & Brewton, K. E. (2014). The role of learning context in high school students’ financial knowledge and behavior acquisition. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(1), 81–94.

Danes, S. M., & Haberman, H. (2007). Teen financial knowledge, self-efficacy, and behavior: A gendered view. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 18(2), 48–60.

De Bock, D., De Win, I., & Van Campenhout, G. (2019). Inclusion of financial literacy goals in secondary school curricula: Role of financial mathematics. Mediterranean Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/2359436?limo=0. Accessed 20th March 2019

Despard, M. R., & Chowa, G. A. (2014). Testing a measurement model of financial capability among youth in Ghana. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 48(2), 301–322.

Harter, C. L., & Harter, J. F. (2009). Assessing the effectiveness of financial fitness for life in eastern Kentucky. Journal of Applied Economics & Policy, 28(1), 20–33.

Harter, C., & Harter, J. F. (2010). Is financial literacy improved by participating in a stock market game? Journal for Economic Educators, 10(1), 21–32.

Heckman, S. J., & Montalto, C. P. (2018). Consumer risk preferences and higher education enrollment decisions. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 52(1), 166–196.

Hinojosa, T., Miller, S., Swanlund, A., Hallberg, K., Brown, M., & O'Brien, B. (2010). The impact of the stock market game on financial literacy and mathematics achievement: Results from a National Randomized Controlled Trial. Evanston: Society for Research on Educational Effectiveness.

Hospido, L., Villanueva, E., & Zamarro, G. (2015, February). Finance for all: The impact of financial literacy training in compulsory secondary education in Spain. Banco de Espana working paper (no. 1502). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2559642 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2559642

Lopez-Fernandez, O., Honrubia-Serrano, L., Freixa-Blanxart, M., & Gibson, W. (2014). Prevalence of problematic mobile phone use in British adolescents. Cyber Psychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(2), 91–98.

Lown, J. M. (2011). Development and validation of a financial self-efficacy scale. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(2), 54–63.

Lucey, T. A., & Cooter, K. S. (Eds.). (2008). Financial literacy for children and youth. Athens: Digital Textbooks.

Lührmann, M., Serra-Garcia, M., & Winter, J. (2015). Teaching teenagers in finance: Does it work? Journal of Banking & Finance, 54, 160–174.

Mandell, L. (2006). Teaching young dogs old tricks: The effectiveness of financial literacy intervention in prehigh school grades. Academy of financial services 2006 annual conference. Salt Lake City, UT.

Mandell, L. (2009). Starting younger: Evidence supporting the effectiveness of personal financial education for pre-high school students. Minneapolis: The National Theater for Children.

Ng, W., & Nicholas, H. (2018). Understanding mobile digital worlds: How do Australian adolescents relate to mobile technology? Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 27(4), 513–528.

Niederjohn, S., & Schug, M. (2006). An evaluation of learning, earning and investing: A model program for investor education. Journal of Private Enterprise, 22(1), 180–190.

Ouma, S. A., Odongo, T. M., & Were, M. (2017). Mobile financial services and financial inclusion: Is it a boon for savings mobilization? Review of development finance, 7(1), 29–35.

Peng, T. C. M., Bartholomae, S., Fox, J. J., & Cravener, G. (2007). The impact of personal finance education delivered in high school and college courses. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28(2), 265–284.

Ranta, M., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2018). Subjective financial situation and financial capability of young adults in Finland. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 42(6), 525–534.

Ratten, V. (2012). Entrepreneurship, e–finance and mobile banking. International Journal of Electronic Finance, 6(1), 1-12.

Serido, J., Shim, S., & Tang, C. (2013). A developmental model of financial capability: A framework for promoting a successful transition to adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(4), 287–297.

Sherraden, M. S., Johnson, L., Guo, B., & Elliott, W. (2011). Financial capability in children: Effects of participation in a school-based financial education and savings program. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(3), 385–399.

Shim, S., Barber, B. L., Card, N. A., Xiao, J. J., & Serido, J. (2010). Financial socialization of first-year college students: The roles of parents, work, and education. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(12), 1457–1470.

Singh, S., Rylander, D. H., & Mims, T. C. (2018). Understanding credit card payment behavior among college students. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 23(1), 38–49.

Smith, R. C., Sharp, E. H., & Campbell, R. (2011). Evaluation of financial fitness for life program and future outlook in the Mississippi delta. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research, 12(2), 25–39.

Suiter, M., & Meszaros, B. (2005). Teaching about saving and investing in the elementary and middle school grades. Social Education, 69(2), 92–95.

Varcoe, K., Martin, A., Devitto, Z., & Go, C. (2005). Using a financial education curriculum for teens. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 16(1), 63–71.

Walstad, W. B., & Rebeck, K. (2016). Test of financial literacy: Examiner’s manual. New York: Council for Economic Education.

Winstanley, M., Durkin, K., Webb, R. T., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (2018). Financial capability and functional financial literacy in young adults with developmental language disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments. https://doi.org/10.1177/2396941518794500.

Xiao, J. J., & O'Neill, B. (2018). Propensity to plan, financial capability, and financial satisfaction. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(5), 501–512.

Xiao, J. J., & Porto, N. (2019). Financial capability of student loan holders: Comparing college graduates, dropouts, and enrollees. Retrieved from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3321898 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3321898

Xiao, J. J., Tang, C., & Shim, S. (2009). Acting for happiness: Financial behavior and life satisfaction of college students. Social Indicators Research, 92(1), 53–68.

Zhang, Y., & Yu, Q. (2018). College students' behaviors of net loans: Status, problems and countermeasures-based on 486 questionnaires of 6 universities. In Proceedings of the 2018 9th international conference on E-business, management and economics (pp. 86–90). New York: ACM.

Zhu, A. Y. F., & Chou, K. L. (2018). Financial literacy among Hong Kong’s Chinese Adolescents: Testing the Validity of a Scale and Evaluating Two Conceptual Models. Youth & Society, https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X17753813.

Acknowledgements

I would also like to thank all adolescent participants and their affiliated schools, for their cooperation and contribution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the Investor and Financial Education Council, Securities and Future Commission, Hong Kong SAR.

Declaration of Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, A.Y.F. Impact of Financial Education on Adolescent Financial Capability: Evidence from a Pilot Randomized Experiment. Child Ind Res 13, 1371–1386 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09704-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-019-09704-9