Abstract

In many countries with apprenticeship-based vocational education and training (VET), dropout from apprenticeship training is a major concern. Leaving an apprenticeship early can be problematic, particularly for young people who do not continue their training at another company or in another occupation, and drop out of the education system without obtaining a qualification. Previous research mostly has used a quantitative design focussing mainly on the perspective of apprentices who left training early and on attributes of the individual that may lead to dropout. Drawing on literature on quality of workplace learning environments, this study used a qualitative comparative approach to analyse the workplace learning environment from the perspectives of both young people who left their apprenticeships early and apprentices at the end of their training. The analysis revealed striking differences between the stayers and leavers in terms of two main characteristics of the workplace learning environment. The findings illustrate how being given responsibility can promote professional development and self-confidence, but also can lead to stress, exhaustion and insecurity if an early transfer of responsibility is not accompanied by support and guidance. Furthermore, the findings emphasise the importance of creating safe learning environments in which apprentices experience support and room for making mistakes. The study concludes that future research may include measures related to transfer and fulfilment of responsibility and handling of mistakes in workplaces to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the processes leading to early contract terminations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In many countries, vocational education and training (VET) plays an important role in labour market entry because it gives young people experience of working life during upper secondary education. This is especially the case in countries where VET is organised as a combination of firm-based vocational training and school-based education, as in Norway, where this study is situated. Research shows that countries with strong apprenticeship systems tend to have a smoother transition into the labour market and less unemployment than others (OECD & ILO, 2017). However, in many countries with apprenticeship-based VET, dropout from apprenticeship training is a major concern. Norway does not report rates of early contract terminations at a national level. Yet, recent figures show that more than 40% of apprentices do not complete their apprenticeships within the standard duration (for most trades) of two years, and that more than 20% do not complete their training after three years (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2020). These figures indicate that a considerable number of apprentices complete VET with delay due to temporary interruptions, e.g. after a change of occupation or company (e.g. Findeisen et al., 2024; Schmid & Stalder, 2012), and that a considerable number of young people drop out of apprenticeship training without any follow-up solutions.

Similar concerns have been raised in various other countries. For example, in Germany and Switzerland, whose VET systems are comparable, about a quarter of all new apprenticeship contracts are terminated early (BFS, 2021; BIBB, 2023). In Germany, this rate has risen steadily over the past 10 years (BIBB, 2023; not enough longitudinal data were available on Switzerland). Although early contract terminations may also be used as a means to improve the training situation by changing company or training programme (as mentioned above), they can be associated with various negative consequences for both apprentices and training companies (e.g. uncertainty, experiences of failure, loss of time and associated costs, see e.g. Findeisen et al., 2024; Schmid & Stalder, 2012). Consequently, early apprenticeship contract terminations have become a serious concern in many countries (for examples from other countries, see Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b)Footnote 1.

According to a recent meta-synthesis, research on early contract terminations mainly has concentrated on identifying learner factors that potentially result in dropout, while far less emphasis has been placed on the learning environment in the workplaces (Böhn & Deutscher, 2022). This one-sided focus is surprising, as research has indicated that learning environment and training quality factors are crucial to persistence and dropout intentions (e.g. Findeisen et al., 2022; Powers, 2020). Therefore, the present study aims to examine how the learning environment in the workplaces might contribute to explain why some apprentices leave their apprenticeships early. We examine this research question by using a qualitative comparative approach and analysing the perceptions and experiences of both leavers (i.e. young people who left their apprenticeships early) and stayers (i.e. apprentices in their final year of training). Böhn and Deutscher (2022) found that the vast majority of studies on dropout in apprenticeship-based VET have used a quantitative design, focussing mainly on the perspective of apprentices who left training early, and they have called on researchers to use more multi-perspective approaches. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have used a qualitative comparative approach. Qualitative comparison groups aim to analyse similarities and differences within and between groups, thereby contributing to a better understanding of lived experiences and processes by revealing how phenomena vary between groups (Lindsay, 2019; Ritchie et al., 2014). As Lindsay (2019) argued, lacking a comparison group often is viewed as a limitation of qualitative studies and may lead to significant biases. Thus, having a comparison group can help enhance rigour and credibility of the findings, thereby strengthening the validity of the data. Therefore, this study seeks to provide new insights into the processes leading to early apprenticeship contract terminations by comparing the experiences of leavers and stayers and by analysing the personal narratives of both groups.

The Norwegian VET Context

The VET system in Norway is integrated into the upper secondary post-compulsory education system, comprising two years of mainly school-based education followed by two years of apprenticeship at a company (known as the 2 + 2 model). This means that young people only start apprenticeship training after two years of school-based training. The apprenticeship period comprises workplace training guided by state-issued curricula in an approved public or private training company. VET leads to more than 180 different trade or worker’s certificates. While it does not provide access to higher education, vocational students who wish to qualify for higher education have the option to replace apprenticeship training with a supplementary year of academic subjects after their second year of VET.

Although young people who have completed compulsory school have a statutory right to upper secondary education and about 98% start upper secondary education immediately after compulsory school (normally at age 16), a large number do not complete it. Recent figures show that one in three VET students does not obtain a trade certificate or a university admission certification within six years (Statistics Norway, 2023). Most drop out during the first two years of education in school or during the transition to apprenticeship training (e.g. due to a lack of apprenticeships). Accordingly, research on dropout from upper secondary education and measures to increase upper secondary completion mainly have focussed on the school-based part of VET or the transition to apprenticeships, while far less attention has been paid to completion of apprenticeship training.

Conceptualising Workplaces as Learning Environments

In this paper, we discuss workplaces as learning environments from two perspectives: first, by using Fuller and Unwin’s (2004) expansive-restrictive continuum, thereby drawing on the conceptualisation of learning as social participation; second, by using the 3-P model of workplace learning by Tynjälä (2013), which aims to identify relations between input and process factors in vocational learning outputs. Both perspectives discuss how the qualities of experiences afforded by workplaces might facilitate or hinder workplace learning.

Fuller and Unwin (2004), among others, found that workplaces differ substantially in how they create opportunities for participation and, therefore, opportunities for learning. The model draws on Lave and Wenger’s (1991) theory on situated learning, in which vocational learning is conceptualised not only as a cognitive process, but also as a social process, involving transitions and identity transformations. Central to the situated learning perspective is the notion of ‘learning as participation’, which suggests that learning is a process of social participation and of gradually being socialised by and into work communities, a process of belonging and becoming and identity formation (Chan, 2013; Colley et al., 2003; Fuller & Unwin, 2004; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998). Hence, it is participation in workplace activities and social interactions that enable novices to learn from more experienced practitioners and move from a marginal to a core position in the work team and full participation in the community of practice. Ideally, the pathway to expert participation is organised with a movement from activities with low complexity, responsibility and error costs to activities that require higher responsibility and complexity where errors may have significant consequences (Billett, 2001; Lave & Wenger, 1991). In the beginning, instruction, guidance and support from experienced others are central for novices’ learning, and trainers and other employees should create an environment of mutual support and allow room for making mistakes (Swager et al., 2015). As the learners gain experience and progress, guidance and feedback are gradually reduced. Moreover, being given responsibility for tasks of increasing complexity is essential for the apprentices’ progression towards independent practice and allows them to become recognised members of the work community (see also Reegård, 2015). Drawing on this conceptualisation of learning, Fuller and Unwin (2004) argued that learners’ transformation and journey depend on the quality of the learning environment that they experience and the extent and richness of available opportunities to participate. In their research, they concluded that expansive learning environments create stronger and richer learning opportunities than restrictive ones, e.g. by providing opportunities for broad participation in the company’s activities and personal development through reflection. Restrictive learning situations, in contrast, involve a narrow conception of participation. The learners are restricted to participation in a limited range of activities and skills on the job (e.g. routine activities with limited complexity and responsibility), and they often remain confined to only one community of practice, with no opportunities for off-the-job training and reflection. Although the learners may become full members of the work community rapidly, their limited set of (production) tasks may reduce the development of expertise (Fuller & Unwin, 2004).

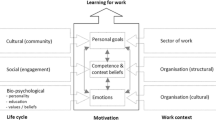

Another way to look at workplaces as learning environments is the 3-P model of workplace learning by Tynjälä (2013), after a modification from Biggs (1993). The model describes the various dimensions connected to learning in a sociocultural environment: presage, process and product. The presage dimension includes both learner factors (e.g. preconditions and motivation) and the learning context (e.g. organisation of work, support). Learning activities, e.g. reflection and evaluation of one’s own work experiences, are represented within the process dimension. Finally, within the product dimension, learning outcomes, e.g. personal or organisational development, are summarised. In addition, an interpretation dimension exists between the presage and process dimensions. By this, the model emphasises the subjective perception and evaluation of learning environments and focusses on the ‘perceived quality’ of the learner (Deutscher & Braunstein, 2023). The model has been used in research on workplace training quality (e.g. Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b) and was operationalised further by Böhn and Deutscher (2021) in a qualitative meta-synthesis of existing survey instruments for quality aspects in VET. In this further development of Tynjälä’s model, input factors (presage) are divided into aspects of the learning environment, framework conditions related to the VET system or the company and personal details. The process dimension comprises the areas of work tasks (e.g. variety, complexity and relevance of tasks), social interaction (e.g. social involvement) and educational mediation (e.g. feedback). The output dimension encompasses learning-related results from the preceding input and process factors, e.g. completion and final exam or early termination of contract. Thus, the model reflects a process-oriented approach to identifying relations between input and process factors in vocational learning outputs.

To sum up, both perspectives presented discuss how workplaces may offer possibilities but also constraints of participation and learning, thereby affecting the learners’ professional development and learning outputs. Thus, early contract terminations may be seen as related to the organisation of work and learning tasks and the learners’ opportunities for participation and interactions in work communities (cf. Fuller & Unwin, 2004; Lave & Wenger, 1991; Tynjälä, 2013). Still, the evaluation of the workplace learning environment relies on subjective perception (Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b; Tynjälä, 2013), and it is the learner’s decision to engage or not in the process of learning (e.g. Billett, 2001).

Early Apprenticeship Contract Terminations and Workplace Learning Environment

The causes of early contract terminations are diverse and heterogeneous and may be related to factors before and after apprenticeships begin (Bednarz, 2014; Bosset et al., 2022; Böhn & Deutscher, 2022; Masdonati et al., 2010; Stalder & Schmid, 2016). In their meta-synthesis, Böhn and Deutscher (2022) identified 68 categories of dropout reasons in apprenticeship, almost half of which represent learner factors (e.g. gender, performance level, migration background). Dropout factors related to the company, school or the apprentices’ work and learning activities have received only scant attention, and the authors asserted that activity factors particularly related to work tasks and learning in the workplace and in vocational school remain a black box to a large extent. However, several studies suggest that reasons related to the workplace learning environment may play an important role in early contract terminations. Indeed, both quantitative and qualitative studies of young people who left their apprenticeships indicate that factors related to the workplace are among the most common reasons for apprentices not completing their training. More specifically, unpleasant work, poor or dangerous workplace conditions, feeling abused or treated like cheap labour, trouble with bosses or colleagues, a lack of training, a lack of qualified staff to provide training and a lack of support are common reasons why many apprentices leave their apprenticeships (Bednarz, 2014; Bosset et al., 2022; Masdonati et al., 2010; Snell & Hart, 2008; Stalder & Schmid, 2016).

While most studies of apprenticeship dropout have been based on retrospective reports by apprentices and may therefore be subject to recall biases (Böhn & Deutscher, 2022), the study by Bosset et al. (2022) confirmed the significance of training conditions, relations and support in the workplace in early contract terminations by using a prospective approach. Apprentices who dropped out of their apprenticeships at a later stage rated skill variety in the workplace more negatively and expressed lower overall satisfaction with the company at the beginning of their training than apprentices who completed their training. Furthermore, what most distinguished stayers from leavers was perceived competencies in and support from their trainers at the beginning of their training. These findings were corroborated by multivariate analysis indicating that the probability of remaining in an apprenticeship is nearly twice as high when apprentices positively rate their trainers’ competencies and workplace support at the start of their training (Bosset et al., 2022).

While the aforementioned studies—along with studies on dropout intentions (e.g. Findeisen et al., 2024; Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b) or on work conditions in certain industries (e.g. Dagsland et al., 2015; Felder et al., 2021)—emphasised the workplace learning environment’s central role in dropout processes and apprenticeship success, other studies called for a more nuanced approach. For example, Negrini et al. (2016) found no linear relationship between training quality in the workplace and early contract terminations. The study found that at companies with trainers who provide high-quality training, the risk of a contract termination is lower. However, companies that provide lower-quality training also may have no contract terminations at all (but also may have many). The study concluded that although high-quality training helps avoid apprenticeship dropouts, high quality alone is not enough. Apprenticeship contract terminations are often the result of a combination of factors (e.g. Masdonati et al., 2010; Stalder & Schmid, 2016), which might at least be mitigated by a positive workplace learning environment (Negrini et al., 2016). Furthermore, expectations and perceptions of training quality in the workplace differ significantly between apprentices and trainers. As shown by multi-perspective studies including the perspectives of both apprentices and trainers, trainers tend to rate training conditions and quality substantially better than do apprentices (Krötz & Deutscher, 2021a; Negrini et al., 2016; Stalder & Schmid, 2016). This finding is important because differences in perceptions of training quality between trainees and their trainers proved to affect dropout intentions significantly (Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b). Nevertheless, early contract termination is the result of an individual’s decision-making process, so the individual’s judgement is crucial, and the perspectives of those involved also might be considered independently of each other (e.g. Böhn & Deutscher, 2022; Stalder & Schmid, 2016).

Method

This study is based on the re-analysis of data from two small-scale interview studies in Norway. We compare and contrast how the workplace learning environment is perceived and described by apprentices in their last year of training, hereafter referred to as stayers (study 1), and young people who left their apprenticeships early, hereafter referred to as leavers (study 2). The aim of the study is to examine how the learning environment in the workplaces might contribute to explain why some apprentices leave their apprenticeships early while others successfully complete their training. Both studies, their participants and data collection procedures are described in the sections below.

Study 1

The first is a longitudinal study on successful pathways through VET among young people perceived to be at risk of not completing their education. The main aim of the study was to identify factors that enable students and apprentices to succeed in both school and apprenticeship despite some form of disadvantage or risk (see e.g. Schmid & Haukedal, 2022; Schmid et al., 2021). The participants were interviewed up to three times. In the study’s first part, we interviewed 25 students in their second year of VET (autumn 2019/winter 2020). The students were recruited from four different upper secondary schools in Oslo and selected based on their grade point average (GPA) from lower secondary school. GPA is the average of all grades from the last year of lower secondary school. Grade scores range from 1 to 6, and a minimum of 2 is needed to pass a subject. The GPA is used as the basis for admission to upper secondary education. All the students in the sample had a GPA below 3.5, which statistically put them in the at-risk group for not completing upper secondary education (cf. NOU, 2018, 15). In the study’s second part, we contacted all of our participants again for a second interview (autumn 2021). Twelve adolescents were in apprenticeship training at that time, and eight were willing to be interviewed a second time. In addition, we conducted an interview with one young person who had started an apprenticeship after the school-based part of VET, but left the apprenticeship early and was not involved in any education or training at the time of the second interview. Most other participants had left VET two years after the first interview and were therefore not the target group for the second interview. Some had switched to a third year of academic subjects and had completed upper secondary education with a university admission certification or were preparing for the examinations. Several participants were (temporarily) out of education and training in autumn 2021, some because they had not found an apprenticeship place. In the study’s third part, five participants were interviewed a third time after completing their education. In the present study, interviews with the eight apprentices (second part of the study) are used to represent the group of stayers. In addition, the interview with the young person who had left the apprenticeship early was added to the interviews with the leavers (see study 2 in the next section).

Most interviews were conducted at the apprentices’ workplaces, one interview was carried out online. The interviews were conducted by all three authors, with the second and third authors involved in the project as research assistants. All young people were interviewed individually with the help of a semi-structured interview guide comprising questions about transition to apprenticeships, their training situation since the start of their apprenticeships to date, and their plans for the future. To capture their perception of the learning environment in the workplaces, they were asked to describe a typical day, their work tasks and responsibilities, guidance, support and relations to trainers and other staff. The average interview duration was 60 min. All participants were informed about the project and research ethics, both in writing and orally, and they all provided consent in writing.

Study 2

The second study was based on a master’s project completed by the second and third authors (Jørstad & Nordlie, 2022), under the first author’s supervision. The project aimed to identify factors that explain apprenticeship contract terminations from different perspectives. For that reason, semi-structured interviews were conducted with six young people who had left their apprenticeships and five representatives from apprenticeship companies or training agencies (spring 2021). In the present study, interviews with the six young people who had left their apprenticeships early were used to represent the group of leavers (together with one leaver from study 1, see section above). Interviews with representatives from apprenticeship companies and training agencies are not used in the present study.

The participants were recruited with help from the Education Agency in Oslo, which is responsible for administering apprenticeship contracts. Young people who had experienced an apprenticeship contract termination no more than half a year ago were invited via text message to take part in a research interview. Six previous apprentices responded to the invitation, and all were interviewed individually by the second and third authors. The interview guide largely contained the same questions as the one used in study 1. In addition, however, the participants were asked about the reasons for terminating the apprenticeship contracts, their decision-making processes etc. The interviews had an average duration of 45 min. All participants gave their written consent to participate.

Participants in the Present Study

In the present study, we focus on our qualitative analysis of data from semi-structured interviews with the eight apprentices from study 1 (second part) and the seven young people who had left their apprenticeships (one leaver from study 1, second part; six leavers from study 2). Thus, the sample for the current study consists of 15 young people; eight stayers and seven leavers.

When applying comparison groups in qualitative research, groups should be as homogenous as possible with respect to relevant characteristics, and they should be recruited from the same or similar locations/populations (Lindsay, 2019; Ritchie et al., 2014). For the present study, the two groups both were recruited from the City of Oslo and were similar with respect to gender, age and social background. The stayers group comprised seven males and one female, all from families with low socioeconomic resources, with most parents in manual or unskilled occupations (e.g. working as cleaners or taxi drivers), unemployed or receiving social benefits. All eight apprentices were born in Norway, and most were age 19 at the time of the interview. The mean GPA in the sample was 2.8. The leavers group comprised four males and three females. Their parents were in similar work situations as the apprentices’ parents, and they were all born in Norway. At the time of the interview, most were between ages 19 and 20, and the mean GPA in the sample was 3.0.

In both groups, the participants represented a variety of different trades (see Table 1). The apprentices in the stayers group came from five different trades: car parts supply; childcare and youth work; motor vehicle; sales; service and administration. The leavers group consisted of young people from six different trades: childcare and youth work; hairdresser; health work; plumber; sales; service and administration.

Hence, the participants in both groups stem from somewhat different trades, which could affect the comparability of their experiences. However, both groups included a representation of social trades (e.g. childcare and youth work), technical trades or trades from the construction sector (e.g. motor vehicles, plumbing) and trades from the field of sales and administration. We therefore consider the two groups to be relatively similar, not only in terms of their social and educational backgrounds but also in terms of the trades they represented. Furthermore, a comparison of the two groups might be facilitated by the fact that the interviews were conducted by the same researchers, who used largely similar interview guides.

Data Analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed in accordance with principles of reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) (Braun & Clarke, 2022) to capture similarities and differences both within and between the two groups of stayers and leavers related to their perceptions and descriptions of the workplace learning environment. We started by exploring the whole data set and coding all the interviews together as one group, not distinguishing between the apprentices and leavers (cf. Lindsay, 2019). This means that we started by using an inductive approach, manually highlighting excerpts that could be of relevance for our research question. During this phase, we worked independently of each other. In the next step, we discussed the independently constructed codes together and considered differences and similarities within and between the groups. Our discussions helped us to achieve a more comprehensive understanding and richer interpretations of the data, as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2022). Furthermore, this process revealed that both groups shared various experiences, e.g. the challenge of adjusting to new demands during the first weeks as an apprentice and the experience of (sometimes) having a low rank as an apprentice or doing work like any other employee without having enough time for reflection. However, we also found striking differences between the two groups’ experiences, particularly in how they described their work tasks, the support they experienced and their feelings about these experiences. In the next step, we used an abductive approach to sort codes into overarching themes. This means that theoretical concepts presented in this paper were combined with findings from our own empirical data. In order to capture those themes that had the most potential to shed light on the two groups’ varying experiences, codes that were similar in both groups (as the examples mentioned above) were not taken into account when creating overarching themes. Consequently, only four codes reached the next step (e.g. ‘proud and self-confident of the responsibility assigned’, see Table 2, second column). The last step involved defining each theme specifically to concisely conveying the essence of the contrasting experiences between the stayers and leavers. At this point, the following main themes were defined: (1) Responsibility that fosters professional development and self-confidence vs. responsibility that causes stress, exhaustion and insecurity; and (2) Workplace climate characterised by mutual support and acceptance of mistakes vs. workplace climate characterised by fear of asking for help and fear of failure. An example of the data analysis procedure is provided in Table 2.

In the following sections, we present the two themes that we identified through our analysis. Anonymised, translated quotations from the interview data are included to illustrate the young people’s experiences and perceptions. Information about workplaces has been withheld to protect the anonymity of our participants and their (former) employers.

Responsibility that Fosters Professional Development and Self-Confidence vs. Responsibility that Causes Stress, Exhaustion and Insecurity

The most striking differences in the stayers’ and leavers’ narratives relate to how both groups talked about responsibility. Responsibility for tasks at the company was a major issue in the interviews with both the stayers and leavers. However, while all the stayers reported about their areas of responsibility at the company with much pride and self-confidence, most of the leavers described the responsibilities they were given as overwhelming, stressful and sometimes exhausting.

The importance of being given significant responsibilities at the company for professional development and self-confidence is illustrated by the example of Kazim, a sales apprentice at a medium-size grocery store. At the time of his interview, he had gained a central position at the store, which he made clear at the beginning of the interview: ‘I don’t want to brag, but I’m one of the best in the shop, if you know what I mean’. Kazim explained that he was responsible for frozen food in the store, as well as beverages—both soft drinks and beer—and that he felt ready for even more responsibilities: ‘Right now, I’d like to take on the dry goods responsibility too. There’s a lot to do in the dry goods departments too. Campaigns and stuff like that’. While his boss asked him to take charge of frozen foods two to three months after he started his apprenticeship, Kazim took the initiative and asked his boss a few months later if he also could be in charge of beverages. He was not satisfied with how the department was managed, noting that the person in charge was ordering beverages that they did not need: ‘I had a chat with the boss, and he asked me: “Do you want to take responsibility”? I just answered: “Yeah, that’s fine”. So, now when the supplier comes, he [the boss] just points at me’. In this way, Kazim became responsible not only for unloading pallets and stocking the shelves, but also for all contact with suppliers and submitting orders. When asked whether he felt he had too much responsibility as an apprentice, he answered the following:

No, I don’t. I think that as an apprentice, I should be able to do everything in the store. Not all at once, but you have to be able to run a store, right, so when the final trade exam comes, I think that if I can do everything in the shop, that’s good for me because I think the next step is to open my own store. I’m thinking of becoming a grocer in [supermarket chain], so it’s how quickly I get that experience that makes it easier for me.

These quotations clearly illustrate how acquiring responsibility and gaining greater autonomy foster professional development in the workplace and increase apprentices’ self-confidence. Kazim viewed himself as an important member of the team who contributes to successful management of the shop with his ability to take responsibility for central tasks in the company’s daily work. Other apprentices provided similar accounts, e.g. Brian, an apprentice in car parts supply. Brian’s boss was so satisfied with Brian’s development in the first year of his apprenticeship that he asked him at the beginning of his second year if he would like a permanent position in the garage after the apprenticeship. Since the company was short of staff at the time, his boss also wanted him to start working with a permanent customer base while he was still in training. Brian said yes straight away:

Now I’m kind of my own boss. I’ve got my own place. I’ve got my own customer base. So, now the customer calls me directly, and I set up an appointment for them, so that’s kind of cool.

Similarly, Tomas, an apprentice in service and administration, explained how he had learnt to manage orders from all over the country, book conference rooms and hotels:

It’s pretty exciting because I think that I’m the one in charge here, in a way. Without me, everything goes to hell. It’s good to feel that I’m doing something important, that I’m doing something really important, in a way, that I’m pushing things forward, in a way.

While receiving and assuming responsibility for tasks at the company was crucial for the stayers’ journey to becoming self-confident young professionals, some stated that they had been struggling at the beginning of their apprenticeships because they were thrown into work tasks from the very beginning and experienced a great deal of responsibility early on. However, all the stayers in our study managed to master their responsibilities successfully, and they were due to take their final trade exams in a few months when we interviewed them. However, a different picture emerged from the interviews with the leavers. Several participants in our study identified the responsibilities they were given at the company as one of the main reasons for leaving their apprenticeships. They all experienced a high degree of responsibility at an early stage, often along with a lack of guidance or support, leaving the apprentices feeling like they were not up to the task, lacking self-confidence and experiencing stress and exhaustion, and sometimes loneliness. One of the leavers who described this was Zoe, who started an apprenticeship in childcare and youth work at a primary school. Although she often worked with one of the teachers and sometimes with other apprentices, she felt overwhelmed at being expected to deal with the children all day, sometimes alone, right from day one:

I think they gave me a lot of responsibility quite early. It wasn’t that I couldn’t handle it, but in a way, it was a lot of pressure on me who was already a bit insecure. /… / I just got really tired.

During the interview, Zoe expressed how she needed more time to get accustomed to her duties and responsibilities at the beginning of her apprenticeship. However, she did not have the courage or confidence to express her needs to her boss. Feeling exhausted, Zoe decided to leave her apprenticeship after only four weeks. Similarly, Emil, a previous apprentice in safety and security services, explained how the responsibility he was given from the very first day caused feelings of insecurity and loneliness, eventually sapping his motivation. Right from his first day at the company, Emil was assigned to stand outside a store and watch for suspicious activity—particularly shoplifting—all on his own. Other times, he was on call for office buildings, which meant that he could be called out when the alarm went off, mostly without assistance from more experienced colleagues. Emil experienced few opportunities for learning or reflection together with other staff or trainers and stated that he ‘was never really trained’. For the young apprentice, the responsibility that he was assigned was overwhelming, and although he worked like other employees at the company, he lacked confidence in his professional skills and felt insecure in many situations that he had to deal with alone:

I dreaded going to work every day. /…/ I didn’t like the job at all, and I was alone most of the time. And it was also a bit unsafe sometimes. /…/ It always went well, but there was always that extra thought in the back of my head, saying, “Things could go wrong”. /…/ The thing was that I felt a lot of responsibility, that I was very much alone all the time.

Having lost his motivation, Emil decided to quit after seven months and take an additional school year, qualifying him for admission to higher education.

Workplace Climate Characterised by Mutual Support and Acceptance of Mistakes Vs. Workplace Climate Characterised by Fear of Asking for Help and Fear of Failure

When it comes to workplace climate, guidance and support, we identified strong differences in our participants’ experiences, both between stayers and leavers, and within the two groups. Nevertheless, we found striking similarities related to how the stayers described relations and social interactions in the workplace, both to their trainers and other employees, compared with the leavers’ narratives. While some of the stayers received close guidance and follow-up from their trainers, with regular meetings and feedback, several had more interaction and collaboration with other employees than their trainers, and they actually experienced more learning situations with other staff than their trainers, often receiving more feedback from them. However, all the stayers in our study developed close and trusting relations in the workplace, and all emphasised that they received help when needed. As service and administration apprentice Tomas put it: ‘I’m not alone. Everywhere I turn, there’s someone ready to help me, in a way’. Other apprentices shared similar statements:

I work on my own a lot; that’s what I do. But if I have a problem, I just ask the person closest to me. (Mario, motor vehicles)

If I can’t handle a situation there and then, I send someone else to do it, and so does everyone else. (Amy, childcare and youth work)

Moreover, the stayers emphasised that a climate of trust and acceptance of mistakes existed, as described by Jake, a motor vehicle apprentice:

For example, if I’ve done something wrong or broken something in the car, he [the boss] says: “You have to be careful, but we’ll fix it”. As long as you tell them that I’ve broken it or done it wrong, or that I’ve fucked up, it’ll be fine, they won’t get angry at all. But if you try to hide it, and they find out, they get angry. As long as you let them know, everything goes well.

While a supportive environment and acceptance of mistakes indicated a recurring theme in the stayers’ descriptions of the workplace learning environment, most of the leavers described an atmosphere in which they were afraid of asking for help and making mistakes. Philipp, a previous apprentice in sales, related the following:

If you know that you’ll most likely be scolded if you don’t do it right, or something like that, then this takes away your motivation. /…/ I’ve been told that when I’ve asked about something twice, they expect me to know it. “That’s exactly what I said earlier”. That takes away your motivation.

Similarly, service and security apprentice Emil experienced little understanding about being insecure and having questions from trainers—although he often had to work alone: ‘I got help if I called and asked how to do this, then they said, “Do it like this”, but then if I rang again, they’d say, “You should be able to do this now”’. For some of the leavers, fear of failure went so far as to make them feel uncomfortable at work, like childcare and youth work apprentice Zoe, who felt discomfort around her boss: ‘We [Zoe and two other apprentices] were kind of … not exactly afraid, but we were a bit, like … it’s hard to explain, it was kind of like “watch out when she comes”, you know?’ For Philipp, Emil and Zoe, the feeling of not being able to fulfil their companies’ expectations of contributing to productive tasks like other employees and a constant fear of failure were important reasons for leaving their apprenticeships. While both Emil and Zoe cancelled their apprenticeship contracts themselves, the boss made the decision for Philipp. As he explained, the climate of mistrust and fear took away his motivation more and more, and he started to neglect work and was often late. When his boss fired him, he was relieved. However, he did not lose the passion for his trade. At the time of the interview, he had just successfully completed the final trade exam after continuing his apprenticeship at another company.

For one apprentice, a mistake, or how a mistake was handled, elicited direct and immediate consequences for his training. Leo, a former childcare and youth work apprentice, was dismissed by his boss for a mistake. At the time of the interview, several months after leaving the company, Leo still was trying to get over it: ‘I think it was very unfair considering that I hadn’t had much guidance’.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study aimed to examine how the learning environment in the workplaces might contribute to explain why some apprentices leave their apprenticeships before completion. The study used a qualitative comparative approach to analyse the workplace learning environment from the perspectives of both young people who had left their apprenticeships early and apprentices in their last year of training. By comparing and contrasting their views and experiences within and between the two groups, we identified two notable differences between the stayers and the leavers.

First, we found striking differences in how the stayers and leavers described their responsibilities with work tasks. The stayers’ narratives illustrated how being able to fulfil assigned responsibilities contributes to learning, professional development and increased self-confidence and, thus, is crucial to becoming full members of the work community. They felt that they were accepted as members of the community because they were trusted and given proper tasks and responsibilities. Most of the leavers, on contrary, described the responsibilities they were given and the expectations placed upon them as overwhelming, stressful, sometimes exhausting and a principial reason for leaving their apprenticeships. Having significant responsibilities is crucial for learning and meaningful participation in work communities, enabling apprentices to become independent and manage increasingly complex tasks (e.g. Fuller & Unwin, 2004; Lave & Wenger, 1991). However, processes of giving and receiving responsibility are embedded in and shaped by social, relational and organisational structures, e.g. professional roles, work tasks and trust relations (Reegård, 2015). Therefore, how responsibility is mastered depends on how work tasks are assigned and how instruction, guidance and support are provided to newcomers. In her study on learning through responsibility in the retail sector, Reegård (2015) concluded that granting (a great deal of) responsibility early on contributes to learning and self-confidence as far as the responsibility is mastered successfully. However, independence and responsibility, along with a lack of guidance, may cause learning stagnation and isolation. Similar conclusions can be drawn from our study. As for the leavers, a fast transition into productive work and a high degree of responsibility early on in their apprenticeships led to insufficient support, guidance and learning opportunities, leaving these young people feeling overwhelmed and exhausted, and sometimes also insecure and lonely, prompting them to leave their apprenticeships and change employers or career paths. Our findings thus indicate that how responsibility is embedded in a learning-supportive and trustful environment and how it is delegated and accompanied through support and guidance are key to success in apprenticeship training.

Second, in close connection with the findings discussed above, the stayers and the leavers in our study differed greatly in how they experienced support and guidance from their trainers or other staff. The extent to which guidance is available and coworkers are willing to assist novice learners and share their knowledge is a key determinant in the quality of workplace learning outcomes (Billett, 2001). In studies on apprenticeship dropout, support (or a lack thereof) consistently is emphasised as a crucial factor, and this usually relates to the availability of support in general, i.e. the trainer/coworkers taking time to answer questions vs. feelings of being left alone (e.g. Bosset et al., 2022; Masdonati et al., 2010; Snell & Hart, 2008). In essence, these practices reveal the different and sometimes contradictory expectations placed on apprentices and whether they are viewed more as legitimate learners or workers (cf. Lave & Wenger, 1991). This also was evident in our study, in which the leavers felt they were expected to contribute in the workplace on a level similar to that of regular employees and that little support was available to them. High expectations and little tolerance for questions led to the leavers suffering from a fear of asking for help and a fear of failure. The stayers, on contrary, described environments in which support was readily available and mistakes were accepted and used as learning opportunities. Thus, our findings emphasise the importance of a culture of acceptance of mistakes in the workplace. Creating safe learning situations in which apprentices experience mutual support and are given room to make mistakes is a central component of workplace guidance in VET (Swager et al., 2015) and may be crucial to success, particularly at the beginning of apprenticeship training.

To sum up, this study identified some of the conditions necessary for apprentices to participate in workplace activities and become members of professional communities, as well as how the learning environment in the workplaces may contribute to early apprenticeship contract terminations. Hence, in terms of practical implications, our findings indicate that early apprenticeship contract terminations are not only related to the learners but also to companies that play a crucial role in creating rich and safe learning environments. The findings highlight that being given significant responsibilities in a workplace is crucial for professional development and self-confidence and, thus, is a prerequisite for becoming a member of the community of practice. However, responsibility and autonomy must not come at the expense of adapted guidance, but should be embedded in an environment in which apprentices receive support and are allowed to make mistakes. Early transfer of responsibility that is not accompanied by support and guidance limits apprentices’ ability to become professionals and may cause stress, exhaustion and a fear of failure—and ultimately can result in dropout. In line with the literature (e.g. Fuller & Unwin, 2004; Lave & Wenger, 1991), our findings highlight the importance of learning environments that encourage broad and meaningful participation in the company’s activities while simultaneously recognising apprentices as legitimate learners.

Finally, our findings largely support previous studies on dropout from apprenticeship training, which identified training conditions and support in the workplace (at least from the young people’s perspective) as important dropout factors (e.g. Bosset et al., 2022; Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b; Stalder & Schmid, 2016). However, questions related to responsibility and the handling of mistakes in workplaces were not examined in previous studies (for an overview, see Böhn & Deutscher, 2022). In‑company training quality commonly is measured using criteria such as variety of tasks, complexity of tasks, overload and autonomy, as well as aspects of social interaction and involvement (e.g. Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b). While some of these concepts relate to each other to some degree (Krötz & Deutscher, 2021b), and increased responsibility often goes along with increased autonomy (Reegård, 2015), our findings nevertheless contribute new insights into the processes leading to early apprenticeship contract terminations. Future research may include measures related to apprentices’ perceptions of transfer and fulfilment of responsibilities, as well as measures related to how mistakes are dealt with in the workplace to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between workplace learning environment and early contract termination.

Limitations of the Study

Although the present study offers several advantages over previous, predominantly quantitative studies, it also contains some limitations. First, this study’s small sample size sets limitations on the conclusions and generalisations that can be drawn from the findings. Generalisability may also be hampered by the fact that not all of the apprentices in study 1 could be reached for an interview, and we may have missed out on relevant experiences. Hence, our findings may to some degree be affected by sample attrition bias. Research with larger samples is needed to shed light on the processes leading to early apprenticeship contract terminations. Second, the interviews with the leavers in this study were conducted up to a few months after the termination of apprenticeship contract. While retrospective reports can provide rich data on past experiences, they can affect the accuracy of recall. For example, the leavers in our study could assess their training situation more negatively in retrospect than they did at the time. Third, while the value of comparative qualitative research lies in understanding how experiences and phenomena vary between groups, the contrasting experiences between groups can lead to differences being emphasised and accentuated. As a consequence, the nuances of different experiences may be neglected. Fourth, the interviews in this study were analysed following the principles of reflexive thematic analysis, which stresses the researcher’s active and reflexive engagement with their data. RTA is an interpretive approach to qualitative analysis that values researcher subjectivity as a resource, and multiple coders are considered beneficial in producing richer interpretations of meaning (Braun & Clarke, 2022). Therefore, in keeping with the underlying philosophy of RTA, intercoder reliability is not accounted for in this study. Fifth, this study focussed on the learning environment in the workplaces and its impact on dropout processes and success in apprenticeships, while other factors potentially resulting in dropout (e.g. related to school or private life) were not considered. However, in most cases, apprenticeship terminations are the result of a combination of factors from different contexts (Masdonati et al., 2010; Stalder & Schmid, 2016). The value of this study lies in providing insights into learning and working conditions in the workplace from the perspectives of both stayers and leavers. Thus, a main strength of this study is its comparative design, which includes personal narratives from both apprentices at the end of their training and young people who left their apprenticeships early.

Data Availability

All data and materials as well as software application or custom code support the published claims and comply with field standards. The interview transcripts generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because they contain data that allows identification of the participants. A limited form of the data can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Custom code.

Notes

Different definitions of apprenticeship contract termination—including actual dropout, as well as change of occupation or company, and different calculation methods—impede comparison of rates of early contract termination between countries, sometimes also within countries (between counties or occupations). For more methodological information, see BIBB (2023, Chapter A5.6) or Schmid (2016).

References

Bednarz, A. (2014). Understanding the non-completion of apprentices. NCVER.

BFS. (2021). Lehrvertragsauflösung, Wiedereinstieg, Zertifikationsstatus. Resultate zur dualen beruflichen Grundbildung (EBA und EFZ). Ausgabe 2021. Bundesamt für Statistik.

BIBB. (2023). Datenreport zum Berufsbildungsbericht 2023. Informationen und Analysen zur Entwicklung der beruflichen Bildung. Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung.

Biggs, J. (1993). What do inventories of students’ learning processes really measure? A theoretical review and clarification. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 63(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1993.tb01038.x

Billett, S. (2001). Learning in the workplace: Strategies for effective practice. Allen & Unwin.

Böhn, S., & Deutscher, V. K. (2021). Development and validation of a Learning Quality Inventory for In-Company training in VET (VET-LQI). Vocations and Learning, 14(1), 23–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-020-09251-3

Böhn, S., & Deutscher, V. (2022). Dropout from initial vocational training – a meta-synthesis of reasons from the apprentice’s point of view. Educational Research Review, 35, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100414

Bosset, I., Hofmann, C., Duc, B., Lamamra, N., & Krauss, A. (2022). Premature interruption of training in Swiss 2-year apprenticeship through the lens of fit. Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Bildungswissenschaften, 44(2), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.24452/sjer.44.2.9

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis. A practical guide. SAGE.

Chan, S. (2013). Learning through apprenticeship: Belonging to a workplace, becoming and being. Studies in Vocational and Professional Education, 6(3), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-013-9100-x

Colley, H., James, D., Diment, K., & Tedder, M. (2003). Learning as becoming in vocational education and training: Class, gender and the role of vocational habitus. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 55(4), 471–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820300200240

Dagsland, Å. H. B., Mykletun, R. J., & Einarsen, S. (2015). We’re not slaves – we are actually the future! A follow-up study of apprentices’ experiences in the Norwegian hospitality industry. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 67(4), 460–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2015.1086411

Deutscher, V., & Braunstein, A. (2023). Measuring the quality of workplace learning environments – a qualitative meta synthesis of employee questionnaires. The Journal of Workplace Learning, 35(9), 134–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWL-06-2022-0074

Felder, A., Duemmler, K., & Caprani, I. (2021). Restrictive and expansive participation in companies’ activities: A case study of bricklaying and automation technology apprentices in Switzerland. Journal of Education and Work, 34(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2020.1858231

Findeisen, S., Jüttler, A., Neuenschwander, M. P., & Schumann, S. (2022). Transition from school to work – explaining persistence intention in vocational education and training in Switzerland. Vocations and Learning, 15, 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-021-09282-4

Findeisen, S., Ramseier, L., & Neuenschwander, M. P. (2024). Changing occupations or changing companies—predictors of diferent types of premature contract terminations in dual vocational education and training programs. Vocations and Learning, 17, 67–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-023-09338-7

Fuller, A., & Unwin, L. (2004). Expansive learning environments: Integrating organizational and personal development. In A. Fuller, A. Munro, & H. Rainbird (Eds.), Workplace learning in Context (pp. 126–144). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203571644

Jørstad, B., & Nordlie, G. S. (2022). Frafall i læretiden. En kvalitativ studie på faktorer rundt årsaker til heving av lærekontrakt sett fra perspektivene til tidligere lærlinger, lærebedrifter og opplæringskontor. Master thesis. Oslo Metropolitan University.

Krötz, M., & Deutscher, V. (2021a). Betriebliche Ausbildungsqualität – Eine Frage Der Perspektive? Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 24(6), 1453–1475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-021-01041-4

Krötz, M., & Deutscher, V. (2021b). Differences in perception matter – how differences in the perception of training quality of trainees and trainers affect drop-out in VET. Vocations and Learning, 14, 369–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-021-09263-7

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lindsay, S. (2019). Five approaches to qualitative comparison groups in health research: A scoping review. Qualitative Health Research, 29(3), 455–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318807208

Masdonati, J., Lamamra, N., & Jordan, M. (2010). Vocational education and training attrition and the school-to-work transition. Education & Training, 52(5), 404–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911011058343

Negrini, L., Forsblom, L., Gurtner, J. L., & Schumann, S. (2016). Is there a relationship between training quality and premature contract terminations in VET? Vocations and Learning, 9(3), 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9158-3

NOU (2018, 15). Kvalifisert, forberedt og motivert. Et kunnskapsgrunnlag om struktur og innhold i videregående opplæring. Kunnskapsdepartementet.

OECD & ILO. (2017). Engaging employers in apprenticeship opportunities. Making it happen locally, Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266681-en

Powers, T. E. (2020). Motivated apprentices: The value of workplace and trade school. Journal of Education and Work, 33(1), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2020.1716309

Reegård, K. (2015). Sales assistants in the making: Learning through responsibility. Vocations and Learning, 8(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-015-9129-0

Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, M., C., & Ormston, R. (Eds.). (2014). Qualitative research practice. A guide for social science students and researchers (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Schmid, E. (2016). Lehrvertragsauflösungen in der Schweiz: Statistische Indikatoren und Quotenberechnung. Empirische Pädagogik, 30(3/4), 356–371.

Schmid, E., & Haukedal, C. L. (2022). Identifying resilience promoting factors in vocational education and training: a longitudinal qualitative study in Norway. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 14(11), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-022-00139-1

Schmid, E., Jørstad, B., & Nordlie, G. S. (2021). How schools contribute to keeping students on track: Narratives from vulnerable students in vocational education and training. Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 11(3), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.3384/njvet.2242-458X.2111347

Schmid, E., & Stalder, B. E. (2012). Dropping out from apprenticeship training as an opportunity for change. In P. Tynjälä, M. L. Stenström, & M. Saarnivaara (Eds.), Transitions and transformations in learning and education (pp. 117–130). Springer.

Snell, D., & Hart, A. (2008). Reasons for non-completion and dissatisfaction among apprentices and trainees: A regional case study. International Journal of Training Research, 6(1), 44–73. https://doi.org/10.5172/ijtr.6.1.44

Stalder, B. E., & Schmid, E. (2016). Lehrvertragsauflösung und Ausbildungserfolg – kein Widerspruch. Wege und Umwege zum Berufsabschluss. hep.

Statistics Norway. (2023). Completion rates of pupils in upper secondary education. https://www.ssb.no/en/utdanning/videregaende-utdanning/statistikk/gjennomforing-i-videregaende-opplaering

Swager, R., Klarus, R., van Merriënboer, J. J. G., & Nieuwenhuis, L. F. M. (2015). Constituent aspects of workplace guidance in secondary VET. European Journal of Training and Development, 39(5), 358–372. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJTD-01-2015-0002

Tynjälä, P. (2013). Toward a 3-P model of workplace learning: A literature review. Vocations and Learning, 6(1), 11–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-012-9091-z

Utdanningsdirektoratet. (2020). Gjennomføring av læretiden 2019–2020. https://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/statistikk/statistikk-fag-og-yrkesopplaring/analyser/gjennomforing-av-laretiden/

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Funding

No funding was received.

Open access funding provided by OsloMet - Oslo Metropolitan University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmid, E., Nordlie, G.S. & Jørstad, B. Workplace Learning Environment and Participation in Work Communities: A Qualitative Comparison of Stayers’ and Leavers’ Perceptions and Experiences. Vocations and Learning (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-024-09351-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-024-09351-4