Abstract

The conceptions of what constitutes nursing competence and how such competence is taught and learned are changing, due to rapid changes in in the health sector. Nurse teachers’ competencies for providing high-quality, up-to-date nursing education, are developing accordingly. This paper reviews the existing research on nurse teachers’ competencies and addresses how this research identifies, describes, and conceptualizes these competencies. A rigorous search, retrieval and appraisal process identified 25 relevant studies for inclusion in the review. A thematic synthesis was applied to the findings of the studies and subsequent themes were synthesized. The thematic synthesis of the empirical evidence resulted in the five broad themes: academic, nursing, and pedagogical competencies; attitudes; management and digital technology. However, these separate elements appeared to be highly integrated. Hence, this paper indicates that nurse teachers’ competencies may be assessed using a holistic approach, which could bring together the disparate attributes required for successful professional performance in specific situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rapid changes in the health sector and the need for professional expertise call for further development of nursing education. The clinical aspects of nursing have become more complex in modern times owing to the aging population, new and complex disease patterns, changes in treatment and work structures, the involvement of more professions, and a higher tempo in the health sector. Therefore, nursing requires increased flexibility, continuing professional development, and lifelong learning. Contemporary nursing involves a combination of different kinds of knowledge, skills, and attitudes, as well as a holistic approach to nursing competence (Cowan et al. 2005). This includes a rather wide scope of knowledge, such as factual knowledge, skillful procedure performance and handling of medicines and equipment, reflective approaches, critical thinking, accurate mastery of patient situations, and interaction with patients and patients’ families. The complexity of patient situations also involves different levels of interdisciplinary collaboration, in which individual professionals need to understand the role of their own discipline, as well as others’ contributions to the collective effort (Barr et al. 2005; Reeves et al. 2008).

The inclusion of nursing education in the category of higher education has also boosted the professionalization process in terms of increasing specialization and complex problem-solving; the development of independent positions in clinical practice, administration, and research; an academically grounded knowledge base; and critical reflection on clinical practice (Potter et al. 2013). In other words, the conceptions of what constitutes nursing competence and how such competence is taught and learned are changing, accompanied by an increasing emphasis on academic knowledge. A heated debate has occurred across national contexts regarding the implications of the strong emphasis on academic knowledge in nursing as a consequence of the shift in nurse education programs from primarily being hospital based to becoming integrated in higher education. For instance, many studies have questioned the relevance of the theoretical dimension of nursing education for clinical practice (Cave 2005; Mackenzie 2009). However, the integration of theoretical knowledge and clinical skills is essential for the quality of students’ learning and professional development (Benner et al. 2010).

Competence areas that are typically recognized as a part of teachers’ knowledge base are subject competence, competence in teaching, competence in classroom management, change and development competence, and an understanding of ethics within the profession (e.g. Postholm 2009; Smith 2011; Mehli and Bungum 2013). The key nursing competencies of nursing students and clinicians/specialists are also widely described in specific nursing studies and literature, existing policies, and reports from professional organizations. The Australian Nurse Teachers’ Society (1998) defines a nurse teacher as follows:

A nurse teacher is an experienced registered nurse who holds, or is undertaking, a professionally recognized teacher education credential, and who integrates research based nursing, management skills, educational knowledge and expertise to achieve learning outcomes that meet the needs of learners and other stakeholders in the educational enterprise. (p. 1).

This definition and Australian nurse teacher professional standards have inspired current efforts to synchronize the competencies, roles, and functions of nurse teachers in European higher education (Education Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency 2012). However, the literature on nurse teachers’ competencies is relatively small, especially from the continental European perspective. The professionalization of nurse teachers, the new context of nursing, and nursing education (research/theory/practice diversity and integration) have called for more detailed descriptions of nurse teachers’ roles and functions. Such specifications could serve to clarify whether a nursing education institution prepares graduates for successful professional practice (Ortelli 2006). In other words, it is important to investigate what makes up professional nursing knowledge and how it is taught and learned – that is, what competencies students need to develop and, therefore, what competencies nurse teachers need to execute to provide high-quality, up-to-date nursing education.

Given this background, this paper seeks to investigate, through a review of empirical studies, how the competencies of nurse teachers are addressed in the existing research. We ask the following research questions: How does the existing research identify, describe, and conceptualize nurse teachers’ competencies? What characterizes this research field in terms of its theoretical framework and empirical tradition?

Conceptual Framework

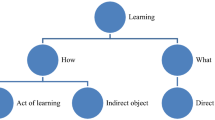

We grounded this study within the concept of professional knowledge integration and recent research on learning. These perspectives enabled the identification of several focus points for the definition of the research questions and the scope of the review. The framework also provided a starting point for conducting a configurative systematic review, which was oriented to interpret and arrange (configure) information (Gough et al. 2012b).

The term professional implies a distinct perspective on what is expected of a qualified nurse and the characteristics of nursing knowledge, particularly the relationship between general knowledge and professional performance in practical settings and specific cases. This challenge is expressed in Abbott’s (1988) definition of professions as “exclusive occupational groups applying somewhat abstract knowledge to particular cases” (p. 8). He adds that this general knowledge is usually acquired through higher education. However, the application of general professional knowledge takes place in practical settings outside the university (Grimen 2008) and requires an integrative approach, which enables integration of the diverse components of professional competencies. With a focus on professional knowledge and a distribution of nursing education between the academically oriented higher education setting and clinical settings, Sullivan’s (2005) categorization of professional education provides a useful analytical approach for conceptualizing nurse teachers’ competence. Professional education programs, Sullivan (2005) argues, are “hybrid, bridge institutions with one foot in the academy, so to speak, and one in the world of practitioners” (p. 25). Sullivan (2005) depicts three apprenticeships that are needed to bring “the disparate pieces of the student’s educational experience into coherent alignment” (p. 208). The first is the intellectual or cognitive apprenticeship emphasizing analytical reasoning, argument, and research. The second is the apprenticeship grounded in practitioners’ professional skills in the work context. The third apprenticeship builds on and integrates the first two and involves the values and attitudes that are shared within the professional community. There is a great educational challenge, Sullivan (2005) argues, in balancing the strengths of academic culture with practical reasoning in initial professional education. Similarly, Benner et al. (2010) identify the potential gaps between the university and professional practice as contexts of learning and highlight new challenges in nursing education. One of those challenges includes nurse education’s response to the rapid changes occurring in clinical practice (e.g., new and complex disease patterns, changes in treatment and work structure, more professions being involved, a high tempo). The compatibility of nurse education programs and current requirements in the health-care sector has become of central importance for securing the quality of patients’ outcomes, as well as the authority and credibility of the profession. Although “it is especially critical to have a clear vision of what high-quality nursing education is and what programs must do to meet those standards” (Benner et al. 2010, p. 7), the pressure to meet these targets creates a risk for lower standards and aspirations. The challenges of contributing successfully to the development of professional nurses can be difficult to overcome for nurse education institutions and their teachers, who are viewed as critical actors in maintaining education quality.

The quality of the learning process depends on teachers’ attitudes toward teaching and learning, students’ active participation, and the positioning of the learning/teaching relationship in the educational process (e.g., McAllister 2001; Nicol 1998; Samuelowicz and Bain 2001). Recent research on learning has had a strong tendency to argue that learning in higher education generally and in nursing specifically is not about prescriptions and routines or learning facts and skills. Instead, education should focus on analytical knowledge, complex problem-solving, professional and social attitudes, identity development, and lifelong learning and professional development (Benner et al. 2010; Hattie 2008; Illeris 2009; Pascarella and Terenzini 2005). This requires accommodative/transcendent and transitional/transformative types of learning and the integration of adequate learning activities into formalized education (Illeris 2009). The integrative pedagogy model (Tynjälä 2007; Tynjälä and Newton 2014) – and the idea of integrative professional learning (Billett 2015; Billett and Henderson 2011), for example – emphasizes the unity of theory and practice. Furthermore, teachers should expand the teaching of abstract knowledge to include situational action and clinical reasoning (Benner et al. 2010) while emphasizing that professional knowledge is heterogeneous and highly fragmented (Grimen 2008). To achieve such a goal, the content of the professional program and the organization of instruction and learning need to be not only grounded in advanced theory and research (Freidson 2001) but also integrated with the challenges of professional practice. Thus, nurse teachers’ embarking on research that informs teaching appears to be of central importance for professional advancement. Although nursing teachers’ competencies have been addressed previously, this article is based on an updated review of the literature that takes the new context of nursing, professional knowledge, and learning into consideration.

Methodology

This review is inspired by the literature on configurative systematic reviews (Gough et al. 2012b). Conducting a configurative systematic review principally means arranging the findings from primary studies to answer the research question. It is an alternative to aggregating the results, for example, in statistical meta-analysis and reviews of effect-size studies (Gough et al. 2012b). Our study has followed the recommended stages for performing a systematic review: initiation of the review by the review team, formulation of review questions and methodology, development of a search strategy, descriptions of study characteristics, quality and relevance assessment, and synthesis (Gough et al. 2012a). In the following sections, we describe the search strategy, selection, summary of the included studies, and analytical approach used in this review.

Database Searches

We conducted a comprehensive literature from November 2015 through February 2016. Diverse databases spanning a number of disciplines, including nursing, medicine, other health professions, health management, psychology, sociology, and pedagogy, were searched so as to have a large number of subjects and breadth of information. The final searches were performed with the databases Academic Search Premier, MEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, OVID, ProQuest, SocINDEX, and ERIC (via EBSCOhost). We also performed manual searches to minimize the limitations that can arise from using predetermined search terms and a controlled vocabulary (Brunton et al. 2012).

We initially chose to use the following keywords: nursing teacher, competences, profession, development, and contribution. Synonyms of these words were then determined using thesauruses (http://www.thesaurus.com and http://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus) and further arranged based on the MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) vocabulary suggestions. The root terms for final query were nursing teacher, competence/professional competence, development/professional development, nursing, and contribution. We then conducted extensive searches using the root terms in various combinations.

Selection of Studies

The searches using the main keywords yielded a large number of studies. When the search was limited to peer-reviewed articles, the number decreased substantially to 638 articles. The main goal of our selection criteria was to define studies that were concerned with nurse teachers’ competencies (Table 1).

The final selection of studies was conducted in three steps. All three authors were engaged in all three stages, and, where necessary, steps were repeated to ensure that the literature was covered comprehensively. In the first stage, we read the titles of the articles and the keywords and selected those articles that matched the research questions (a total of 136 studies). In the second stage, we read the abstracts and checked them based on the inclusion criteria. Electronic searches showed that many studies employ the same terms but do not share the same focus (Gough et al. 2012a). After excluding duplicate articles and evaluating the abstracts, we were left with 81 full-text articles. For those abstracts considered relevant to the research questions, we retrieved the full-text papers for further reading. After a proper examination of the full-text articles, we compiled a list of the final studies to be included. In the relatively large body of literature that we searched, nurse teachers’ competence was seldom addressed explicitly; 37 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review. In the third stage, we derived criteria for identifying and evaluating studies from checklists for critical review of the research literature (Long et al. 2002). We analyzed the studies based on the following factors: how the ideas were organized; what methods were used to study the problem; what theories were used to explain, predict, or understand the research problem; what sources were cited to support the conclusions; and how the key points were illustrated. Thus, we could see the particular research question(s) and purpose of each article in relation to the research questions in this paper. Through this process, we eliminated 12 more articles because of focus incompatibility or lack of explicit methodological descriptions. The selection process ultimately resulted in 25 articles being included in the final review. A flow chart providing a detailed illustration of the search trail is included in Fig. 1.

Summary of the Reviewed Studies

The included studies are summarized to provide detailed information on aim/research question, theoretical/conceptual framework, methods, findings, conclusions, and recommendations (Appendix Table 3). The studies were conducted in the United States, Australia, and various European countries.

The types of analytical strategy used in the empirical studies were clearly defined in 17 articles, whereas the research strategy was not specified in eight studies. Eleven of the articles located the study within a defined theoretical/conceptual foundation. The theoretical foundations included a wide range of approaches, as indicated in Appendix Table 3. The other 14 articles had no explicit theoretical or conceptual framework.

In total, 13 articles used qualitative methods, eight articles were based on descriptive or inferential statistics, and two articles combined quantitative and qualitative methods. The qualitative studies mentioned – to a varying extent – inductive, discourse analytical, phenomenographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and thematic approaches to data analysis. The preferred methods for data collection were fixed-response self-completed questionnaires and face-to-face interviews. The sample sizes in the reviewed articles ranged from six to 317 in the qualitative studies and from 104 to 549 in the quantitative studies. Students (1799 in six articles) and nurse teachers (1364 in 15 articles) were the main study participants. Mentors and nurses in general were the target populations in a smaller number of the articles, as well as nurse leaders in health institutions (64) and administrators in educational institutions (17). Students were the main participants in the quantitative studies.

The term nurse teacher appeared to be associated with faculty/academia, whereas the terms nursing educator, clinical teacher, nurse preceptor, and mentor were used to describe nurses who guide students in health-care institutions during periods of practice. The term link teacher was used for faculty members who are responsible for following students in practice. In this paper, the term nurse teacher is used for faculty-employed staff, whereas the term mentor refers to nurses employed by health institutions who are responsible for following students in clinical practice.

Ethical concerns were addressed in all empirical studies. The qualitative studies were more focused on the ethical issues than the quantitative studies were, particularly regarding the methods of data collection. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Analytical Approach

The primary studies identified in configurative reviews can be often heterogeneous and thus involve interpretive analysis. Hence, we applied a thematic synthesis (Thomas et al. 2012) to bring together findings from different types of research. This was performed in five steps:

-

1)

We began the analysis by becoming familiar with the body of data: Findings were read and reread to become familiar with commonalities and differences across the studies.

-

2)

We extracted data from each study using Oliver and Sutcliffe’s (2012) practicalities for the description and analysis of studies. We used MAXQD11 software (2015) to organize the data.

-

3)

We identified and analyzed the concepts that emerged from the data extracted from the qualitative studies first. By closely examining the individual studies, we identified codes. These codes involved identification of full sentences that had consistent meanings. The codes were then organized into subcategories. We then grouped similar subcategories together.

-

4)

Next, we assessed the mixed-methods and quantitative studies. We repeated the processes of step 3 and placed the results of the coding into the emergent subcategories.

-

5)

We reexamined the identified subcategories to determine how they were connected. The emergent subcategories were, in this process, reduced to 10 subcategories with merging of some of the smaller subcategories. In this stage of the synthesis, we also explored similarities and differences across subcategories. Finally, those 10 subcategories were organized into five main themes, as described in the section below.

Results

The thematic synthesis of the empirical evidence resulted in the five major themes:

-

academic competencies, including academic knowledge and academic practice;

-

nursing competencies, including nursing knowledge and nursing practice;

-

attitudes, including personal characteristics and professional attitudes;

-

pedagogical competencies, including pedagogic knowledge and pedagogic practice; and

-

management and digital technology.

Numerical evidence is summarized in Table 2.

The quantitative distribution of the themes and subcategories allowed us to visualize the data – that is, the relationship between the themes according to the frequency of identified codes (MAXQD11 software 2015). The software indicates the percentage of codes related to each theme (see Fig. 2).

The main themes contributed to separate elements of nurse teachers’ competence. In the following section, we describe how the different elements are addressed in the existing research, as well as how they can be viewed as a complementary set of nurse teachers’ competencies.

Nurse Teachers’ Academic Competencies

Academic knowledge was emphasized in several of the review studies, yet nurse teachers’ academic competencies appeared to represent a complex combination of academic knowledge and practice. The recent requirements for nurse teachers within academia, including a doctoral degree, scholarship, and involvement in research, appeared to be of central importance (Ramsburg and Childress 2012). Participants in the study by Logan et al. (2015) identified their own issues in terms of the need to gain further research education and a higher level of qualification (PhD) and gave some indication of the intense pressure on academics to increase publishing outputs. However, concern about the possible decline in value of the doctoral degree – and of the profession – because of the pressure to produce large numbers of doctoral graduates in a short timespan also arose (Jackson et al. 2011). The introduction of new requirements for faculty teaching represented a massive cultural shift for many involved in nursing education, serving as an explanation for the existing tension within nursing education institutions and between these institutions and the practical field (Jackson et al. 2011). Nurse teachers in the study by Logan et al. (2015) underlined that they had entered higher educational institutions without understanding the need for doctoral studies and research. This increasing pressure to be both academically and clinically credible, argued Johnsen et al. (2002), was creating conflict for teachers dealing with the theory–practice nexus. Mathisen and Bastoe (2008) raised a concern about the possible danger to nursing identities if nurse teachers change their focus from clinical knowledge to research. Guy et al. (2011) also illuminated the difficulties in changing the “old” nurses’ mindset, including their interest and involvement in integrating research and clinical practice. Furthermore, researchers showed that “being an academic” was seen as distinct from teaching (Logan et al. 2015) and that possessing scientific skills was not important to all teachers in higher education (Tigelaar et al. 2004).

Some of the reviewed studies also addressed issues of academic practice by focusing on how the growth in nursing and educational research, which has coincided with the transition of nursing education from practical training to university education, has resulted in sophisticated, personalized evidence-based care and evidence-based teaching. Löfmark et al. (2012) gave an example of the use of nursing research in decision-making as expressed in students’ learning outcomes within the academic knowledge area. Meanwhile, Salminen et al. (2013) argued that applying the newest research-based knowledge resulted in nursing being based on the most recent developments. However, nurse teachers’ workload and lack of time for research limited their involvement in research (Logan et al. 2015; McAllister et al. 2011). According to Logan et al. (2015), developing the next generation of academics as both researchers and teachers requires the establishment of nursing as a research-based discipline, which would imply that doctoral and postdoctoral positions provide undergraduate teaching.

Nurse Teachers’ Nursing Competencies

Nurse teachers’ skills in nursing practice represented an issue of concern in fifteen studies. The importance of clinical credibility and the idea that maintaining and improving nurse teachers’ clinical competencies secures success in students’ learning experiences and guarantees a high level of teaching were stressed (Fisher 2005; Mathisen and Bastoe 2008; Salminen et al. 2013). Gardner (2014) argued that nurse teachers need to be good nurses first and foremost, whereas Fisher (2005) and Ramsburg and Childress (2012) indicated differences in points of view on the importance of clinical competencies between different groups involved in nursing education. However, students and clinical personnel highlighted that “nurses become faculty members because they could not cut it in the real world” (Gardner 2014, p. 109). Although nursing knowledge can be considered to encompass nursing science, philosophy, theory, and practice – as well as general medical and social knowledge, psychology, related laws and regulations, ethics, and relevant research – this concept received limited discussion in the reviewed articles. The performance of nursing skills in clinical tasks was a central consideration, whereas nurse teachers’ theoretical and research-based knowledge received substantially less attention. However, the need to combine theoretical and clinical nursing was emphasized in several studies (Fisher 2005; Mathisen and Bastoe 2008; Salminen et al. 2013) and was viewed as essential for dealing with changing health-care trends (Guy et al. 2011; Salminen et al. 2013). Meanwhile, identity and values developed through engagement in nursing practice could conflict with those of academia (Logan et al. 2015). For example, some of the mentors appeared to be extremely skilled in performing technical tasks and routines but ignorant of the theoretical professional background or evidence-based practice and research: Forbes (2011) pointed out that the mentoring process was colored by mentors’ diverse and potentially conflictual understanding of nursing, which might range from a lost patient focus to a focus on holistic nursing care. Brown et al. (2012) stated that when mentors who are good role models are available in the ward, students’ attitudes toward nursing were more positively shaped. The mentors’ engagement in “mothering work” was at odds with the concept of the student as a self-reliant adult learner (McKenna and Wellard 2009), thereby reinforcing the status quo by facilitating the continuation of current nursing practices in particular departments. This situation embodies a culture of managerialism rather than a culture of learning. Furthermore, McAllister et al. (2011) depicted the issue of “pro training” and an “anti-education” culture in health services. The participants in that study expressed the opinion that leaders in clinical environments were generally unsupportive of the mission of education and were focused on mandatory training for the health services workforce; they failed to appreciate that students are learners who need guidance, appraisal, support, and encouragement. The need to highlight the role of the practical arena was crucial according to Brown et al. (2012), whose study indicates that clinicians act as gatekeepers of the requisite knowledge and skills that students need to gain so as to exist within the nursing culture. The possible implications for nurse teachers went unaddressed. Although nurse teachers’ visibility in the clinical area was appreciated, the role of nurse teachers as clinical facilitators was not identified in the reviewed studies.

Ramsburg and Childress (2012) emphasized that teaching, rather than clinical experience, leads to knowledge acquisition for nurse teachers. However, educational institutions have a tendency to employ temporary staff without heeding the standard procedures and requirements for nurse teachers (Peters et al. 2011). A problem can arise when temporary teachers move into permanent full-time roles as academic staff but do not have an adequate understanding of the responsibilities of permanent academic teachers (Jackson et al. 2011; McDermid et al. 2013). Ultimately, compromise in any aspect of learning and teaching quality in nursing programs could affect patient care negatively.

Nurse Teachers’ Attitudes

In seventeen of the reviewed articles, nurse teachers’ attitudes were addressed, although to different extents. Attitudes were primarily seen as a combination of personal characteristics and professional attitudes. Personality characteristics included the individual nurse teacher’s attitudes, emotional tendencies, and character traits that might affect teaching, nursing, and interpersonal relationships (Salminen et al. 2010). Displaying a sense of humor, admitting one’s own limitations and mistakes, exhibiting self-control, being cooperative and patient, showing enthusiasm for teaching, and being flexible were described in many of the reviewed studies (Brancato 2007; Cook 2005; Hanson and Stenvig 2008; Johnson-Farmer and Frenn 2009).

Professional attitudes received substantially more attention than personality factors. Strong opinions were expressed about the experienced differences between permanent and seasonal employees in their levels of engagement, commitment, accountability, and allegiance to the nursing program and students (Brown et al. 2012; Gardner 2014; McAllister et al. 2011; McDermid et al. 2013; Peters et al. 2011). Brancato (2007) suggested that empowering teaching behavior could vary among nurse teachers depending on the kind of nursing program they attended, the number of empowerment courses they completed, their highest educational degree attained, and their sense of psychological empowerment. Conversely, the isolation of nurse teachers was attributed to a lack of communication and mentoring from other educators, a relatively remote geographical location, a lack of opportunity to network with educators in the same area of expertise, a lack of access to educational resources, and contrasting viewpoints within a facility’s staff (McAllister et al. 2011).

Nurse Teachers’ Pedagogical Competence

Although the issue of pedagogical knowledge and practice was addressed as an issue of concern in several articles, it was not a separate focus in any of the articles. Brown et al. (2012) related the acquisition of knowledge to the pedagogical competencies of the nurse teacher. Johnson-Farmer and Frenn (2009), Lee et al. (2002), and Hanson and Stenvig (2008) connected pedagogical knowledge to the efficiency of education and the active use of competencies and teaching strategies, which involved challenging students by using critical thinking in problem-solving and providing opportunities for students to contest standard knowledge. Gardner (2014) argued that teaching style, knowledge of teaching, learning theories, and pedagogical knowledge constitute nurse teachers’ pedagogical competence. Teachers who replicated teaching strategies from their own past prolonged an undesirable situation. Logan et al. (2015) added that “teaching only” and viewing teaching as the passing down of knowledge to the next generation of nurses had a negative impact on the nurse teachers’ progress up the academic ladder.

Several studies on nurse teachers’ competence also addressed issues regarding teaching and learning approaches. Guy et al. (2011) addressed nurse teachers’ preparation for teaching and the importance of developing competence in teaching. In particular, Löfmark et al. (2012) indicated the need for creating relevance in teaching, including linking theoretical to practical knowledge; forging connections between life, practice, and the classroom; engaging students in dynamic learning; and paying attention to the different backgrounds and experiences of students. Tigelaar et al. (2004) strongly supported teaching approaches in which the student is seen as an active self-regulated learner.

Student achievement was addressed in four articles. Assessment of written assignments was discussed, as well as work overload and disparities in permanent and seasonal staff in the use of assessment criteria (McAllister et al. 2011; McDermid et al. 2013; Peters et al. 2011). Some of the studies referred to teacher experience, the use of case studies and examples from practice in teaching, and the impact of promoting students’ reflection and development of critical thinking on students’ learning. For instance, Johnson-Farmer and Frenn (2009) reported how students’ involvement in research was useful in developing students’ understanding and direct involvement in nursing practice. Evaluation in the clinical practice was not mentioned.

Technology Use and Management Skills

A number of recent studies have reported that the use of digital technology in teaching to ensure ongoing information exchange and maintain contact between teachers and students poses a challenge for nurse teachers (Gardner 2014; Guy et al. 2011; Mathisen and Bastoe 2008; McAllister et al. 2011; Saarikoski et al. 2009). The need for changes in pedagogical practices was also highlighted, such as the use of digital technology, so as to accommodate modern students. Thus far, nurse teachers tend to use technology to change the mode of teaching, not the content (Gardner 2014). Interestingly, electronic support for learning in terms of the online learning environment appeared to be unexplored.

Nurse teachers perform within different levels of management hierarchy simultaneously and appear to be involved in the planning, organization, coordination, leadership, and control of activities, as well as the direct implementation of plans, so as to achieve defined objectives. Interestingly, participants in the study Ramsburg and Childress (2012) indicated that nurse teachers have very low self-confidence in their ability to lead, to bring about change, to participate in ongoing quality improvement, to advocate for nursing in the political arena, and to strike a balance between teaching, scholarship, and service. They argued that institutions need to provide support and encouragement to nurse teachers. Brancato (2007) suggested that the active participation of the faculty in decision-making within nursing programs was important for the success of the educational environment. Moreover, Guy et al. (2011) showed nurse teachers’ limited power or influence in the development of budget and educational policies and procedures and in the promotion of nursing and nurse education in the political arena. Simultaneously, the competition for time was highlighted with respect to the heavy teaching loads and organizations’ priorities (Logan et al. 2015). A sense of belonging or assimilation into an organization or society and an understanding of the mentality of the institution have been shown to be vital for both nurse teachers and students (Brown et al. 2012). In addition, cooperation and collaboration emerged central for nurse teachers in maintaining clinical links and visibility, as well as an opportunity to act as change agents, to promote the credibility of the teacher, and to keep abreast of the political climate and organizational issues (Fisher 2005; Saarikoski et al. 2009; Guy et al. 2011). McAllister et al. (2011) stressed the unique challenges of a nonvalidating culture and pointed to a need to support each other within educational and health-care institutions.

Discussion

This review investigates how nurse teachers’ competencies have been addressed in the existing research, as well as what has characterized this research. In this last section, we elaborate further on our research questions. First, we discuss how competencies can contribute to professional knowledge building and transformation within and between the contexts of research, education, and the workplace. Second, we address some empirical characteristics of the reviewed research. Third, we consider the strengths and limitations of this review.

Nurse Teachers’ Competencies

In response to the first review question, we recapitulate the main findings in light of our analytical perspectives and discuss three aspects of nurse teachers’ competencies: the need for an integrative approach to nurse teachers’ competencies, the implications for pedagogical qualities in nursing education, and the relationship between individual and collective competence at the program level.

The differences in the understanding of nurse teachers’ competencies and their conceptualizations can be seen as multidimensional. One dimension involves the development of professional nursing practice in the specific context of the national health-care system, as underlined by Keskinen and Silius (2005). In another dimension, the individual’s professional attitudes and understanding constitute a central issue (McAllister 2001; Nicol 1998; Samuelowicz and Bain 2001). Other dimensions involve a basic understanding of professional nursing (Benner et al. 2010; Hattie 2008; Illeris 2009; Pascarella and Terenzini 2005; Potter et al. 2013), as well as the political/professional agendas and interests and the diversity of key stakeholders’ perceptions of nurses and expectations from nursing education (Benner et al. 2010; Keskinen and Silius 2005). A final dimension focuses on issues regarding the understanding of theoretical, research-based, and experience-based knowledge and the applications of these types of knowledge in practical settings (Freidson 2001; Grimen 2008; Sullivan 2005), placing integration (Benner et al. 2010; Sullivan 2005) and the learning/teaching relationship in a central position (Barr and Tagg 1995; Illeris 2009; Nicol and Macfarlane-Dick 2006; Slavin 1996; Topping 1998; Zimmerman and Schunk 2001). A closer examination of this multidimensional discussion suggests that links between professional education, fields of professional practice, and the professional community do not seem to be well developed, although the existing literature views these links as necessary for the establishment of cognitive apprenticeship (Benner et al. 2010; Brown et al. 1989; Sullivan 2005).

Nonetheless, ongoing rapid changes in the health sector and the need for further development of high-quality, updated nursing education presupposes the continuous development of nurse teachers. Nurse teachers are expected to succeed in the dual role of nurse and teacher. Their performance has to be recognized as legitimate by both those who inhabit the domain of nursing practice and those who inhabit the domain of academia (McNamara 2009). In addition, the role of nurse teachers has expanded to include that of researcher (Griffin et al. 2005; Hinshaw 2001). Despite the discerned heterogeneity, we argue that nurse teachers actually have a quintuple role – that of professional nurse, teacher, researcher, manager, while skilled use of digital technology is implied. Changes in technology are occurring not only in health-care settings but also in the educational environment. The use of technology was reported in six of the reviewed studies, but the online learning environment did not receive any particular attention, despite the fact that nurse teachers appeared to struggle with and be challenged by it. Furthermore, our findings indicate that today’s nurse teachers are also expected to have management skills. This was mentioned but not further illuminated in the reviewed research, despite the fact that this requirement corresponds with the definition of a nurse teacher put forward by the Australian Nurse Teachers’ Society ( 1998, 2010) and is fully consistent with contemporary demands on nurse teachers. Autonomy in decision-making is an inherent aspect of accurate and high-quality mastery of specific patient situations. For this reason, it is a central nursing function and the basis for the concept of total quality management of patient situations (Potter et al. 2013). Rapid changes in work structures and requirements for complex problem-solving at the institutional level in health services have also increased the development of a highly demanding administrative role for nurses (Marquis and Huston 2012). Similarly, nurse teachers require competencies for management at the professional, personal, and institutional levels, specifically the organization of programs/curricula and nursing education.

The integration of research, theory, and practice has major implications for the development of evidence to inform the practical and theoretical knowledge of the discipline. Achieving clinical excellence was deemed a prerequisite for nursing academics, whereas possessing a nursing/caring background was acknowledged to be invaluable to the role of a nurse teacher. However, across the reviewed studies, a possible divergence between identity and values developed in practice and those of academia was illuminated. The move from hospital schools to the unfamiliar university setting has been, and still is, a complex and challenging process for nursing education, stemming from the fact that the academic field of nursing has experienced challenges in adapting the principles underpinning the discipline and the demands of research-intensive universities (McNamara 2009). The findings indicate that possessing academic competencies (as the development of research-based knowledge to inform practice) still does not appear to be widely accepted as a precondition for being a nurse teacher, with the roles of teacher and researcher being considered separate. Similarly, Dupin et al. (2015) provided evidence that nurses focused on fulfilling either research or nursing roles, not both; in addition, nurses’ apprenticeship in research depended on its perceived usefulness in optimizing patient care and on its direct connection to practice. It appears that nurse teachers’ engagement with research is dependent on the perceived usefulness for and direct connection to healthcare rather than to pedagogical practice. Despite contemporary requirements for research and a clear need for contributions to the body of knowledge within the discipline, it appears that nurse teachers’ own research activities are still infrequent. Moreover, differences in nurse teachers’ conceptual understanding and the requirements for their research and development practice were evident in the reviewed studies. Research that informs teaching enables teachers and institutions to make productive decisions about educational activities and provide opportunities for students’ learning (e.g., Ramsden 2003). Thus, the representations that nurse teachers have of research that might inform teaching and the potential impact of such research on their professional practice as teachers require further investigation.

Ultimately, we suggest taking an integrative approach to developing nurse teachers’ competencies, which implies including and balancing academic excellence, nursing excellence, pedagogical qualifications, and management skills. This is in line with Sullivan’s (2005) argument for taking discontinuities in professional education as a starting point and for bridging the gap between academia and the world of practitioners. It is also in line with arguments for a holistic approach to nursing competencies (Cowan et al. 2005; Thompson 2009). A challenge then could be to ensure a certain combination of professional attitudes in terms of engagement, commitment, accountability, and allegiance to the school and students, which includes respect for the diversity and multiple positions needed to ensure high-quality nursing education. Adopting an integrative approach could be an effective strategy for bringing together the disparate attributes required for professional performances in specific situations, as argued in research on professional learning and development (Billett 2015; Billett and Henderson 2011; Tynjälä and Newton 2014). However, this approach can also be seen as so broad and profound that it becomes meaningless to attempt to achieve or apply it fully.

The question of how to achieve this must also be viewed as a question about the practices of teaching and learning in nursing education, which to a lesser extent is illuminated by Benner et al. (2010) and Sullivan (2005). The main purpose of initial nursing education is to prepare graduates to function as professional nurses in a variety of settings. Specifically, this type of education should bring together attitudes, knowledge, and skills required in the real world of the complex health-care setting. Upon graduation, students should have an understanding of the diverse aspects of nursing competencies and demonstrate commitment to an integrative, holistic approach in balancing and prioritizing specific situations. Thus, the relatively weak links across different contexts of nursing education and the fragmentation of nurse teachers’ knowledge base can be seen as evidence of a contradiction between the existing reality of nursing education and the stated educational goals.

Nursing education occurs in a dynamic context in the real world, operating at a crossroads between a specific health-care environment, the professional community, and academia. In that sense, nursing education can be understood as a widely distributed dynamic process, where individual nurse teachers’ competencies comprise only one part. Therefore, we raise the question whether individual nurse teachers can achieve excellence in all the different competencies required of them today. Moreover, although the findings indicated isolation in the teacher position, education is not an isolated activity. Cooperative and collective actions are needed, and nursing education depends on interactions among groups of nurse teachers who are more specialized in one (or some) of the fields of expertise than in others. Nurse teachers’ competence could, in this respect, be conceptualized beyond the characteristics of individual competencies and also include competence at the program level, as a collegial quality, in which the complementary competencies of collegial nurse teachers mesh across fields and domains of expertise within the nursing community (Salomon 1993) and affirm plural commitment, respect, and loyalty to one’s self and others (Antonovsky 1993). In that sense, a suggested solution for the current problem of complexity in nurse teachers’ competencies may involve building strong team competencies and collaborative and communicative settings within nurse education institutions.

Characteristics of the Reviewed Studies

In response to the second review question, we found that the reviewed research studies shared some characteristics worthy of special note. First, the majority of the reviewed articles had no explicit study design. Moreover, several studies lacked a theoretical or conceptual framework. It could be argued that this is somewhat common in nursing research, which is not a specific research field. For example, nursing within academia has been described as weak in visibility and academic performance, producing low-quality outputs and lacking a research culture (Thompson 2009). Typically, research-based knowledge is explicit rather than tacit (Harden and Gough 2012). It is produced on the basis of a specific goal or research question (de Vaus 2001) and requires conceptual and methodological rigor. Consequently, further initiatives are needed to develop nursing generally and nurse education specifically as a research-based discipline.

Second, the review found that highly diverse empirical traditions are represented in the studies. Most were based on surveys or interviews, with focus group discussions being the least preferred method. None of the reviewed articles included observation as the main or additional data collection method. This minimal use of interaction data could imply that the current body of research lacks perspective on how nurse teachers’ competencies are enacted and also is relatively weak on addressing institutional and educational processes (Little 2012). Observation studies could therefore be an important addition to self-reported data, such as surveys and interviews, in further research on nurse teachers’ competencies. In addition, none of the studies had a longitudinal design allowing for following development over time, which could be another focus area for future research. It could also be desirable to attempt to relate nurse teachers’ competencies to achievements of student learning. The use of theoretical approaches that seek to explain processes and changes in competencies (e.g., liberal and organizational learning) could therefore be an important asset in further studies so as to add additional perspectives to the current studies that use checklists and self-reporting.

Third, although all the included studies focused on developed countries and were similar in some respects, the results point toward possible contextual and cultural differences in nurse teachers’ competencies. Conducting comparative studies may shed light on the general underlying structure that allows for variation. Linking studies on teacher competencies in other fields of professional education could be an important resource for comparison: Are competence requirements similar across field, or are certain requirements specific for nurse teachers? In addition, contextual differences could be taken into consideration when transferring checklists for use in other countries.

Strengths and Limitations

This literature review was limited by the number of available and relevant empirical studies (25) focusing on nurse teachers’ competencies, published post-2000 in English and Scandinavian languages and conducted in developed countries. Many of the included studies displayed limitations that decreased rigor. However, the evidence found is of sufficient and appropriate quality and relevance for configurative purposes and configuration of the research field (Gough et al. 2012b). Furthermore, a small sample size, common in qualitative research, decreases the generalizability of the studies; however, all the included studies were similar in some respects. The results point to possible contextual differences and the findings of the reviewed studies may not be generalizable to particular settings or populations. Nevertheless, there does appear to be a high level of potential transferability, and this review can inform the understanding and development of nurse teachers’ competencies.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to investigate how nurse teachers’ competencies are addressed in the existing research and to provide a body of knowledge concerning nurse teachers’ competencies. A clear and common categorization of nurse teachers’ competencies was not found, and the understanding and conceptualization of their competencies varied. However, the reviewed body of research provided a rationale for suggesting an integrative approach to nurse teachers’ basic competencies, bringing various aspects of professional knowledge and practice together and taking into account contemporary contexts of nursing. This study has acknowledged the growth of the professional knowledge base in the interaction between research, education, and the workplace; the complexity of integration, and the challenges in achieving a holistic approach. To respond to the challenges of developing nursing as a valuable professional discipline, nurses, nurse teachers, researchers, and institutions must take a constructive approach that acknowledges the existing complexity and profound challenges facing nursing in general and academic nursing in particular.

References

Abbott, A. (1988). The system of professions: an essay on the division of expert labor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Antonovsky, A. (1993). Complexity, conflict, chaos, coherence, coercion and civility. Social Science & Medicine, 37(8), 969–981.

Australian Nurse Teachers’ Society (ANTS). (1998). Australian nurse teacher competency standards. Retrieved from http://www.ants.org.au/Download/Ntcomp1.pdf.

Australian Nurse Teachers’ Society (ANTS). (2010). Australian nurse teacher professional practice standards. Retrieved from http://www.ants.org.au.

Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: a new paradigm for undergraduate education. Change, 27(6), 13–25.

Barr, H., Koppel, I., Reeves, S., Hammick, M., & Freeth, D. (2005). Effective interprofessional education: argument, assumption and evidence. Oxford: Blackwell.

Benner, P., Sutphen, M., Leonard, V., & Day, L. (2010). Educating nurses: a call for radical transformation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Billett, S. (2015). Integrating practice-based learning experiences into higher education programs. New York: Springer Science. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-7230-3_1.

Billett, S., & Henderson, A. (Eds.) (2011). Promoting professional learning. New York: Springer Science. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-7230-3_1.

Brancato, V. C. (2007). Psychological empowerment and use of empowering teaching behaviors among baccalaureate nursing faculty. Journal of Nursing Education, 46(12), 537–544.

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42.

Brown, J., Stevens, J., & Kermode, S. (2012). Supporting student nurse professionalisation: the role of the clinical teacher. Nurse Education Today, 32(5), 606–610.

Brunton, G., Stansfield, C., & Thomas, J. (2012). Finding relevant studies. In D. Gough, S. Oliver, & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (pp. 107–135). London: Sage.

Cave, I. (2005). Nurse teachers in higher education – without clinical competence, do they have a future? Nurse Education Today, 25(8), 646–651.

Cook, J. L. (2005). Inviting teaching behaviors of clinical faculty and nursing students’ anxiety. Journal of Nursing Education, 44(4), 156–161.

Cowan, D. T., Norman, I., & Coopamah, V. P. (2005). Competence in nursing practice: a controversial concept – a focused review of literature. Nurse Education Today, 25(5), 355–362. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2005.03.002.

de Vaus, D. A. (2001). Research design in social research. London: Sage.

Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA)/Eurydice/Eurostat/Eurostudent. (2012). The European higher education area in 2012: Bologna process – Implementation report. doi:10.2797/81203.

Dupin, C. M., Larsson, M., Dariel, O., Debout, C., & Rothan-Tondeur, M. (2015). Conceptions of learning research: variations amongst French and Swedish nurses. A phenomenographic study. Nurse Education Today, 35(1), 73–79.

Fisher, M. T. (2005). Exploring how nurse lecturers maintain clinical credibility. Nurse Education in Practice, 5(1), 21–29.

Forbes, H. (2011). Clinical teachers’ conceptions of nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 50(3), 152–157.

Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism: the third logic. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gardner, S. S. (2014). From learning to teach to teaching effectiveness: nurse educators describe their experiences. Nursing Education Perspectives, 35(2), 106–111.

Gough, D., Oliver, S., & Thomas, J. (2012a). Introducing systematic review. In D. Gough, S. Oliver, & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (pp. 1–17). London: Sage.

Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012b). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1(28). Retrieved from http://www.systematicreviewsjournal.com/content/1/1/28.

Griffin, G., Green, T., & Medhurst, P. (2005). The relationship between the process of professionalization in academe and interdisciplinarity: a comparative study of eight European countries. Kingston upon Hull: University of Hull.

Grimen, H. (2008). Profesjon og kunnskap [Profession and knowledge]. In I. A. Molander & L. Terum (Eds.), Profesjonstudier [the study of profession] (pp. 71–87). Oslo: Universitesforlaget.

Guy, J., Taylor, C., Roden, J., Blundell, J., & Tolhurst, G. (2011). Reframing the Australian nurse teacher competencies: do they reflect the “REAL” world of nurse teacher practice? Nurse Education Today, 31(3), 231–237. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.10.025.

Hanson, K. J., & Stenvig, T. E. (2008). The good clinical nursing educator and the baccalaureate nursing clinical experience: attributes and praxis. Journal of Nursing Education, 47(1), 38–42.

Harden, A., & Gough, D. (2012). Quality and relevance appraisal. In D. Gough, S. Oliver, & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (pp. 153–179). London: Sage.

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Hinshaw, A. S. A. (2001). Continuing challenge: the shortage of educationally prepared nursing faculty. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 6(1), Manuscript 3, 1–9.

Illeris, K. (Ed.) (2009). International perspectives on competence development: developing skills and capabilities. New York: Routledge.

Jackson, D., Peters, K., Andrew, S., Salamonson, Y., & Halcomb, E. J. (2011). “if you haven’t got a PhD, you’re not going to get a job”: the PhD as a hurdle to continuing academic employment in nursing. Nurse Education Today, 31(4), 340–344. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2010.07.002.

Johnsen, K. Ø., Aasgaard, H. S., Wahl, A. K., & Salminen, L. (2002). Nurse educator competence: a study of Norwegian nurse educators’ opinions of the importance and application of different nurse educator competence domains. Journal of Nursing Education, 41(7), 295–301.

Johnson-Farmer, B., & Frenn, M. (2009). Teaching excellence: what great teachers teach us. Journal of Professional Nursing, 25(5), 267–272.

Keskinen, S., & Silius, H. (2005). Disciplinary boundaries between the social sciences and humanities: National report on Finland. Retrieved from http://www.york.ac.uk/res/researchintegration/.

Lee, W.-S., Cholowski, K., & Williams, A. K. (2002). Nursing students’ and clinical educators’ perceptions of characteristics of effective clinical educators in an Australian university school of nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 39(5), 412–420.

Little, J. W. (2012). Understanding data use practices among teachers: the contribution of micro-process studies. American Journal of Education, 118(2), 143–166.

Löfmark, A., Thorkildsen, K., Råholm, M.-B., & Natvig, G. K. (2012). Nursing students’ satisfaction with supervision from preceptors and teachers during clinical practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 12(3), 164–169.

Logan, P. A., Gallimore, D., & Jordan, S. (2015). Transition from clinician to academic: an interview study of the experiences of UK and Australian registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(3), 593–604.

Long, A. F., Godfrey, M., Randall, T., Brettle, A. J., & Grant, M. J. (2002). Developing evidence based social care policy and practice. (Part 3): Feasibility of undertaking systematic reviews in social care. Project report. Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health, University of Leeds.

Mackenzie, K. M. (2009). Who should teach clinical skills to nursing students? British Journal of Nursing, 18(7), 395–398.

Marquis, L. B., & Huston, J. C. (2012). Leadership roles and management functions in nursing (7th ed.). [Kindle version]. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Mathisen, J., & Bastoe, L.-K. H. (2008). An unending challenge: how official decisions have influenced the teaching of nursing in Norway. International Nursing Review, 55(4), 387–392.

MAXQDA 11. (2015). [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.maxqda.com/download/New-Features-in-MAXQDA-11.pdf.

McAllister, M. (2001). Principles for curriculum development in Australian nursing: an examination of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 21(4), 304–314.

McAllister, M., Williams, L. M., Gamble, T., Malko-Nyhan, K., & Jones, C. M. (2011). Steps towards empowerment: an examination of colleges, health services and universities. Contemporary Nurse, 38(1–2), 6–17.

McDermid, F., Peters, K., Daly, J., & Jackson, D. (2013). “I thought I was just going to teach”: stories of new nurse academics on transitioning from sessional teaching to continuing academic positions. Contemporary Nurse, 45(1), 46–55.

McKenna, L., & Wellard, S. (2009). Mothering: an unacknowledged aspect of undergraduate clinical teachers’ work in nursing. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 14(2), 275–285.

McNamara, M. S. (2009). Academic leadership in nursing: legitimating the discipline in contested spaces. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(4), 484–493. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01014.x.

Mehli, H., & Bungum, B. (2013). A space for learning: how teachers benefit from participating in a professional community of space technology. Research in Science & Technological Education, 31(1), 31–48. doi:10.1080/02635143.2012.761604.

Nicol, D. J. (1998). Using research in learning to improve teaching practice in higher education. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving student learning: improving students as learners (pp. 86–96). Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development, Oxford Brookes University.

Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: a model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199–218.

Oliver, S., & Sutcliffe, K. (2012). Describing and analysing studies. In D. Gough, S. Oliver, & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (pp. 135–153). London: Sage.

Ortelli, T. A. (2006). Defining the professional responsibilities of academic nurse educators: the results of a national practice analysis. Nursing Education Perspectives, 27(5), 242–246.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (2005). How college affects students: Vol. 2. A third decade of research. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Peters, K., Jackson, D., Andrew, S., Halcomb, E. J., & Salamonson, Y. (2011). Burden versus benefit: continuing nurse academics’ experiences of working with sessional teachers. Contemporary Nurse, 38(1–2), 35–44.

Postholm, M. B. (2009). Research and development work: developing teachers as researchers or just teachers? Educational Action Research, 17(4), 551–565. doi:10.1080/09650790903309425.

Potter, P. A., Perry, A. G., Stockert, P., & Hall, A. (2013). Fundamentals of nursing (8th ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier.

Ramsburg, L., & Childress, R. (2012). An initial investigation of the applicability of the Dreyfus skill acquisition model to the professional development of nurse educators. Nursing Education Perspectives, 33(5), 312–316.

Ramsden, P. (2003). Learning to teach in higher education (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Reeves, S., Zwarenstein, M., Goldman, J., Barr, H., Freeth D, Hammick, M., et al. (2008). Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 1, Art. no.: CD002213. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002213.pub2.

Saarikoski, M., Warne, T., Kaila, P., & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2009). The role of the nurse teacher in clinical practice: an empirical study of Finnish student nurse experiences. Nurse Education Today, 29(6), 595–600. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2009.01.005.

Salminen, L., Stolt, M., Saarikoski, M., Suikkala, A., Vaartio, H., & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2010). Future challenges for nursing education – a European perspective. Nurse Education Today, 30(3), 233–238.

Salminen, L., Minna, S., Koskinen, S., Katajisto, J., & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2013). The competence and the cooperation of nurse educators. Nurse Education Today, 33(11), 1376–1381.

Salomon, G. (Ed.) (1993). Distributed cognitions: psychological and educational considerations. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Samuelowicz, K., & Bain, J. D. (2001). Revisiting academics’ beliefs about teaching and learning. Higher Education, 41(3), 299–325.

Slavin, R. E. (1996). Research on cooperative learning and achievement: what we know, what we need to know. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 21(1), 43–69.

Smith, K. (2011). The multi-faceted teacher educator: a Norwegian perspective. Journal of Education for Teaching, 37(3), 337–349. doi:10.1080/02607476.2011.588024.

Sullivan, W. M. (2005). Work and integrity: the crisis and promises of professionalism in America (2nd ed.pp. 1–33). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Thomas, J., Harden, A., & Newman, M. (2012). Synthesis: combining results systematically and appropriately. In D. Gough, S. Oliver, & J. Thomas (Eds.), An introduction to systematic reviews (pp. 179–227). London: Sage.

Thompson, D. R. (2009). Is nursing viable as an academic discipline? Nurse Education Today, 29(7), 694–697. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2009.03.007.

Tigelaar, D. E. H., Dolmans, D. H. J. M., Wolfhagen, I. H. A. P., & van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2004). The development and validation of a framework for teaching competencies in higher education. Higher Education, 48(2), 253–268.

Topping, K. (1998). Peer assessment between students in colleges and universities. Review of Educational Research, 68(3), 249–276.

Tynjälä, P. (2007). Perspectives into learning at the workplace. Educational Research Review, 3(2), 130–154. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2007.12.001.

Tynjälä, P., & Newton, J. M. (2014). Transitions to working life: securing professional competence. In S. Billett, C. Harteis, & H. Gruber (Eds.), International handbook of research in professional and practice-based learning (pp. 513–533). Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-017-8902-8_19.

Wolf, Z. R., Bender, P. J., Beitz, J. M., Wieland, D. M., & Vito, K. O. (2004). Strengths and weaknesses of faculty teaching performance reported by undergraduate and graduate nursing students: a descriptive study. Journal of Professional Nursing, 20(2), 118–128.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (Eds.) (2001). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: theoretical perspectives. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the Centre for the Study of Professions’ research group on professional knowledge, qualification, and coping for their helpful and stimulating discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was procured for the development of this literature review.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zlatanovic, T., Havnes, A. & Mausethagen, S. A Research Review of Nurse Teachers’ Competencies. Vocations and Learning 10, 201–233 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9169-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-016-9169-0