Abstract

Purpose of Review

The management of shoulder instability in throwing athletes remains a challenge given the delicate balance between physiologic shoulder laxity facilitating performance and the inherent need for shoulder stability. This review will discuss the evaluation and management of a throwing athlete with suspected instability with a focus on recent findings and developments.

Recent Findings

The vast majority of throwing athletes with shoulder instability experience subtle microinstability as a result of repetitive microtrauma rather than episodes of gross instability. These athletes may present with arm pain, dead arms or reduced throwing velocity. Recent literature reinforces the fact that there is no “silver bullet” for the management of these athletes and an individualized, tailored approach to treatment is required. While initial nonoperative management remains the hallmark for treatment, the results of rehabilitation protocols are mixed, and some patients will ultimately undergo surgical stabilization. In these cases, it is imperative that the surgeon be judicious with the extent of surgical stabilization as overtightening of the glenohumeral joint is possible, which can adversely affect athlete performance.

Summary

Managing shoulder instability in throwing athletes requires a thorough understanding of its physiologic and biomechanical underpinnings. Inconsistent results seen with surgical stabilization has led to a focus on nonoperative management for these athletes with surgery reserved for cases that fail to improve non-surgically. Overall, more high quality studies into the management of this challenging condition are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Shoulder instability in the throwing athlete can be caused by acute trauma, as is the case with an acute subluxation or dislocation, but more commonly occurs through an insidious process of microtrauma and pathologic adaptations. [1] These repetitive mini-traumas lead to microinstability, which most commonly manifests with symptoms of anterior instability in throwers, but can also occur with posterior and multidirectional instability (MDI). [2, 3] No gold standard for management of these injuries exists, and throwers must be treated on a case-by-case basis. The goals of treatment are to correct underlying pathological derangement or injuries while not impairing the physiologic adaptations that have allowed exceptional performance. A trial of nonoperative management is typically the first-line of treatment. If conservative therapy fails, a series of arthroscopic and open procedures exist with a variable track record for successful return to sport. This review will describe the evaluation, management and anticipated outcomes of throwers with shoulder instability. It should be noted that limited data exist for throwers, specifically, who represent a very specialized group, so much of the information presented here will be extrapolated from subgroup analysis of broader studies in overhead athletes or athletes, generally.

The Concept of Microinstability

An understanding of the management of shoulder instability in the throwing athlete necessitates a preliminary discussion on the concept microinstability. In the throwing athlete, normal, physiologic adaptations to the static and dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder occur in response to repetitive stresses enabling them to generate enormous torque and peak throwing velocities. [4, 5] However, a delicate balance exists between these physiologic adaptations and the development of pathologic changes leading to abnormal glenohumeral biomechanics. [2] This pathologically increased amount of shoulder laxity is referred to as microinstability when it leads to symptoms, such as shoulder pain or a sensation of instability.

Microinstability classically affects throwing athletes who perform repetitive abduction-external rotation movements as part of their sport, such as baseball players. [2, 6, 7] It is closely related to the concept of internal impingement, which is defined by Walch and colleagues as abnormal contact between the articular surface of the rotator cuff and the posterosuperior glenoid labrum. [8] This phenomenon has been previously associated with a host of different intraarticular pathologies. [2, 9,10,11,12,13,14] It is critical to note, however, that microinstability can be associated with instability in any direction: anterior, posterior or multidirectional. [15].

Clinical Evaluation of Shoulder Instability

History

Shoulder instability in throwing athletes uncommonly presents as a result of acute trauma. [16] In the rarer cases where it does, players will report a traumatic event, such as running into a wall or sliding awkwardly into a base, leading to frank subluxation or dislocation. More commonly, throwing athletes will report vague arm pain or subtle subluxation events in the setting of microinstability. Often they will not be able to clearly articulate the direction of their instability and in some cases, may not recognize instability as an issue. It is critical for providers to attempt to localize the area of pain, understand the duration and severity of symptoms, and identify any aggravating positions or activities. These athletes may report shoulder pain while throwing (commonly during the late cocking phase), decreased velocity and post-shoulder throwing weakness. [2, 17] In the case of anterior instability, throwers will typically report symptoms in positions of shoulder abduction and external rotation. Posterior instability more commonly presents with apprehension in abduction and internal rotation.

Physical Exam

The goals of the physical exam in a throwing athlete are to pinpoint the direction of instability and establish the severity of symptoms. This process must necessarily distinguish between physiologic laxity and pathologic instability. Given the wide range of shoulder pathologies seen in throwing athletes and concomitant pathologies that can be observed with internal impingement [2, 9,10,11,12,13,14], a full shoulder physical examination should be performed. Visual inspection and palpation of the shoulder can identify anatomic asymmetries as well as help to localize pain. Specific attention should be paid to assessing posterior glenohumeral joint line pain, internal rotation deficits and increased external rotation, and positive apprehension testing. [2, 17] Patients may have a positive posterior impingement sign as described by Meister [18], whereby the patient’s pain is reproduced when palpating the posterior glenohumeral joint line with the arm in the late cocking phase (i.e., 90–110° of abduction, slight extension, maximum external rotation). Comparing range of motion between affected and contralateral shoulders can help assess for functional or pathologic laxity.

A series of provocative maneuvers should be performed to help identify the direction and degree of instability. The apprehension and relocation tests are often positive in the case of anterior instability. Both anterior and posterior load and shift tests can be performed to help identify the direction of instability. The Kim and Jerk Tests are both performed to test for posterior instability. The O’Brien test may have some utility in identifying posterior labral pathology in overhead athletes. MDI is less common in throwers, but typically presents with a positive sulcus sign on exam. [19] These patients commonly experience generalized ligamentous laxity and may have elevated Beighton scores although the reliability of these tests has been questioned [20].

Imaging

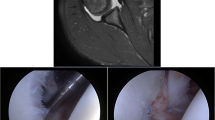

The evaluation of instability in throwing athletes should include a series of radiographs to include a true glenohumeral anterior to posterior view, internal and external rotation views, scapular-Y views and an axillary view. While typically normal, one may occasionally see calcification of the inferior glenohumeral ligament/posteroinferior capsule (i.e., Bennet lesion), greater tuberosity sclerosis, osteochondral defects in the posterior humeral head, and/or flattening of the glenoid rim. [2, 17, 21] The gold standard for evaluation of shoulder instability remains magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which allows for fine detail of soft-tissue structures implicated in instability, including the labrum, capsule and rotator cuff. MRI in isolated microinstability is also often equivocal, though can be notable for increased capsular volume or inferior glenohumeral ligament thickening. [17, 22] When internal impingement is present, partial undersurface tears of the rotator cuff, humeral head cysts or impaction fractures and posterosuperior labral damage may be appreciated (Fig. 1). [2, 17, 21] In cases of MDI, it is common to see a patulous inferior capsule representative of capsular laxity. [23] Computed tomography (CT) scans are typically reserved for evaluation and quantification of bone loss in cases of traumatic dislocation or where significant humeral head or glenoid defects are seen on plain radiographs.

MRI of 40-year-old minor league baseball pitcher with internal impingement A. Coronal Inversion Recovery image demonstrates partial articular sided supraspinatus tear. B. Coronal proton density image demonstrates type 2B superior labrum anterior to posterior (SLAP) tear. C. Axial proton density image demonstrates posterior superior labral tearing

Nonoperative Management

As previously discussed, the majority of shoulder instability in throwers is caused by pathologic changes to the shoulder joint with time and repetitive overhead motions. [24] As a result, the first line treatment is rarely surgical regardless of instability direction, unless there is significant bone loss or other significant intraarticular injuries. Special considerations must be made for athletes who are in-season. Team physicians must necessarily balance the goal of a safe return to sport with the athlete’s competitive drive to return to play (RTP) [25].

For all types of instability, RTP criteria includes pain-free and full range of motion, full strength and an absence of apprehension on physical exam. [26] In the case of traumatic injury, this often occurs reliably within a month of injury. [26] However, the results are less predictable in cases of microinstability and may depend on the demands of an athlete’s individual sport as well as the severity of injury.

Anterior Instability

Anterior shoulder instability is the most common type of instability seen in throwers and non-throwing athletes alike. [16, 22] No optimal rehabilitation regimen exists, however, stepwise physical therapy programs are typically focused on rebalancing and strengthening the shoulder joint through a combination of posterior capsule stretching coupled with rotator cuff and scapular stabilizer strengthening. [2, 26, 27] Data suggest structured posterior capsule stretching programs improve internal rotation and potentially create more space for the humeral head, which may temporarily or permanently improve patients’ symptoms in microinstability cases. [28, 29] Sport-specific rehabilitation exercises are only initiated once pain-free and full range of motion and near-full strength is achieved [30].

Limited outcomes data exist for nonoperative management of anterior atraumatic shoulder instability, especially for throwers. In one study from the United Kingdom, a series of functional outcome measures, including the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI) and Oxford Instability Shoulder Score (OISS), improved in a cohort of patients who underwent physical therapy for atraumatic instability. [31] Notably, however, this was a demographically diverse group rather than just throwers.

In the cases of traumatic instability, outcomes of nonoperative management for anterior shoulder instability demonstrate reasonable and expedited RTP rates but a high rate of recurrent instability. [25, 32] Buss et al. followed athletes after initial anterior shoulder instability events. Mean RTP time for athletes was 10.2 days with 87% of athletes returning within the same season. However, they reported 37% of athletes ultimately experienced an additional shoulder instability event during the season and 53% underwent off-season surgical shoulder stabilization. [33] Hurley et al. performed a systematic review to ascertain RTP rates after initial episodes of anterior shoulder instability in athletes treated nonoperatively. They determined that 76.5% of athletes were able to RTP and 51.5% were able to return to pre-injury levels. Recurrence rate of shoulder instability was 54.7% in this cohort. [34] These studies demonstrate that nonoperative management can be an effective short-term management option for athletes, but comes with a high risk of recurrent instability.

Posterior Instability

Throwing athletes less commonly experience posterior instability. The hallmark treatment remains nonoperative management with a staged therapy protocol focused on shoulder stabilizers, core strengthening, balance and proprioceptive training with a gradual return to sport-specific activities. This rehabilitation program should involve careful oversight by certified therapists used to working with throwing athletes [35, 36].

Very few studies exist looking at clinical outcomes and return to sport in throwing athletes with posterior instability. A series of 19 patients who experienced atraumatic posterior shoulder subluxation by Blacknall et al. examined their clinical outcomes with physical therapy. They noted improved in OISS scores by 18.6 points and WOSI scores by 37%. None of the patients reported lingering shoulder issues that prevented their continued participation in hobbies and sports. [37] Importantly, however, this was not a group of throwing athletes, who likely place more stress on the glenohumeral joint. A recent systematic review demonstrated favorable results in terms of pain, recurrent instability and functional outcomes for rehabilitation programs focused on scapular control, posterior rotator cuff and deltoid. This was, however, also not specific to throwing athletes. [35] A separate series published by Lee et al. had more mixed results at long-term follow up. Of 37 patients with posterior instability (9 overhead athletes) who were treated nonoperatively, more than half (54%) experienced continued or worsened pain in the affected shoulder. There were 3 patients with recurrent instability who had experienced an initial traumatic dislocation. No patients with atraumatic instability experienced a recurrent episode of instability [38].

Multidirectional Instability

The management of MDI remains a significant challenge. While more common with overhead, nonthrowing athletes such as swimmers, MDI can affect throwers as well. [39] There is frequently a degree of baseline ligamentous laxity in athletes who present with MDI. In order to compensate for the laxity of static stabilizers of the shoulder, physical therapy programs focus on effective strengthening of the dynamic stabilizers of the shoulder, including the rotator cuff and periscapular muscles.

A series of different rehabilitation programs have been proposed in the literature for the management of MDI. [40,41,42] An example is the Watson Instability Program, which is a stepwise physical therapy protocol focused on rotator cuff and deltoid strengthening in patients with MDI. While not specific to throwing athletes, this program has shown promise through improvements in strength, scapular motion and functional outcomes in patients with MDI. [43, 44].

Operative Management

Surgical management of shoulder instability in throwing athletes is typically reserved for cases of failed nonoperative treatment, unless there is an indication for primary surgical stabilization (e.g., fracture, significant bone loss or concomitant rotator cuff injury). Athletes should be aware that outcomes and RTP for throwers after surgical stabilization is unpredictable. Nonetheless, in cases of refractory pain, surgery is a reasonable option that may alleviate symptoms and help restore prior level of performance. Surgical decision-making must balance a need for shoulder stability with concerns for not only time lost from sport, but also the potential for surgical overtightening of soft tissues, which may limit postoperative range of motion and impact performance.

No clear consensus exists for best approach to the surgical management of instability in throwing athletes. Surgical options are broad and include various different soft tissue and bone augmentation procedures. Overall differences in management relate to patient and surgeon preference and comfort level, historical training and geography.

Anterior Instability

The spectrum of conditions that encompasses anterior instability ranges from cases of subtle microinstability with or without labral tearing to those with large glenohumeral bone defects in the setting of recurrent dislocations. The assortment of surgical procedures for its treatment is consequently diverse, including arthroscopic and open capsulolabral repair, remplissage and bone augmentation surgery.

Studies suggest during examination under anesthesia (EUA) and diagnostic arthroscopy, patients with microinstability may have a grade II or III load-and-shift test and a positive drive-through sign [2, 45] while their shoulder may appear largely normal without significant labral or cuff tearing or fraying. This absence of a clear surgical target creates a challenge for orthopedic surgeons managing symptomatic microinstability. Historical approaches included isolated arthroscopic labral or partial rotator cuff debridement and thermal capsulorrhaphy. However, concern over poor outcomes from isolated debridement and postoperative range of motion deficits associated with global thermal capsulorrhaphy has limited their use [46,47,48].

Results appear to be more favorable with capsular plication using suture. Jones et al. [49] found a 90% return to sport rate (85% at preinjury level) without any loss of range of motion among 20 overhead athletes undergoing arthroscopic capsular plication with either suture alone or suture anchors for microinstability. At a mean 3.6 years follow-up, average Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic scores were 82 and there were no complications. The precision associated with suture may provide superiority over global thermal shrinkage with respect to maintaining range of motion [2, 49].

In addition to arthroscopic plication, anterior capsulolabral reconstruction (ACLR) has been used to treat microinstability. Jobe et al. [50] originally described a 68% rate of excellent clinical outcomes and RTP among 25 overhead athletes undergoing open anterior capsulolabral reconstruction. Montgomery and Jobe [51] subsequently described superior outcomes after further modifications to this technique, with 94% of 31 athletes undergoing open ACLR returning to sport (81% at the same level of competition). Most recently, Funakoshi et al. [52] documented substantial PROM improvements and an 83% return to prior level of competition among 12 elite baseball players suffering from internal impingement and anterior microinstability following ACLR with hamstring autograft, although external rotation was significantly decreased by an average of 9° postoperatively.

The typical treatment of traumatic anterior instability without bone loss is arthroscopic stabilization, which has a mixed track record in throwing athletes (Figs. 2 and 3). Park et al. examined the outcomes of 51 elite baseball players after arthroscopic stabilization for anterior instability. They defined RTP as return to at least one game, and solid return to play (sRTP) as return to > 10 official games. Overall RTP and sRTP rates were 82% and 80% respectively. However, closer analysis showed that pitchers who had surgery on their throwing arm had RTP and sRTP rates of 20% and 0% respectively. Surgery on the dominant arm was associated with worse RTP. [53] In a group of 49 overhead athletes out of the Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) Shoulder Instability Consortium undergoing primary arthroscopic shoulder stabilization for anterior shoulder instability, RTP was 63% at 2 years, but only 45% reported returning to the same level of competition. Surgery consistently restored motion despite persistent subjective looseness in roughly a quarter of patients. [54] Harada looked at a series of 24 young overhead athletes who underwent arthroscopic Bankart repair for anterior instability and found no episodes of recurrent instability with notable improvements in range of motion. Similarly, only 62% of patients reported the ability to return to pre-injury performance level. Average time to RTP was 6.5 months, but closer to 13 months for return to previous performance level[55].

Proton Density MRI sequences of a 22- year- old male with shoulder pain and instability. A. Coronal slice demonstrating anterior and inferior capsulolabral disruption B. Axial MRI demonstrating small Hill-Sachs lesion C. Axial MRI demonstrating anterior and inferior labral tearing D. Sagittal MRI at the level of the glenoid demonstrating no significant glenoid bone loss

Remplissage may be considered in cases of large Hill-Sachs lesions and concern for recurrent instability. [56] In a study looking at outcomes and return to sport after remplissage by Garcia et al., a subgroup of overhead athletes reported nearly 66% had issues with throwing postoperatively and 58% reported altered mechanics after surgery. 34% reported decreased velocity, 17% had pain with throwing and 58% were stiff. RTP was only 51% in this subgroup. [57] In contrast, Kirac et al. performed a study to compare the results of isolated arthroscopic Bankart repair compared to combined Bankart repair with remplissage in a group of 64 overhead athletes with anterior shoulder instability. They demonstrated significant improvement in all functional outcomes in both groups, with decreased rates of recurrent instability, apprehension and higher return to sport and previous level of play in the remplissage group. This cohort did experience restricted range of motion when compared to the Bankart repair group, however, this did not impact overall patient satisfaction. [58] While the Anterior Shoulder Instability International Consensus (ASI) group published recommendations in 2022 discouraging the use of remplissage in throwing athletes due to concern over alteration of throwing mechanics and consequent impact on performance, these new data raise the possibility that remplissage may be benefit certain overhead and throwing athletes with large humeral sided bone defects and instability. [59].

In the setting of significant glenohumeral bone loss, bone augmentation procedures are performed to restore anterior stability. The most commonly performed bone augmentation procedure is the Latarjet. Bauer et al. examined a group of 18 professional handball players for a total of 20 shoulders with anterior shoulder instability and successfully underwent open Latarjet procedures. RTP in any league was 85%, and RTP at same level of professional handball was 80% at an average of 5 months. Notably, 11.1% of athletes ended up retiring after surgery due to the shoulder, and one case of recurrent instability was seen (5%). [60] Brzoska et al. performed a study analyzing 46 professional athletes with recurrent anterior shoulder instability undergoing an arthroscopic Latarjet procedure, which included 11 overhead athletes. RTP and RTP to pre-injury levels in the overhead athlete cohort were 90.1% and 81.8%, respectively. Average time to RTP was 5.3 months. [61] Finally, Frantz et al. performed a study that analyzed the outcomes of 65 athletes (37% overhead) undergoing Latarjet for anterior instability. They found that 55% of patients failed to meet RTP criteria [62].

Recently, interest in other bone augmentation procedures, including distal tibial allografts and distal clavicle autograft transfers, have garnered interest. These have mostly been used in the setting of recurrent instability or failed Latarjet procedures. Preliminary data for these techniques are promising, but further research is warranted to better understand appropriate indications and outcomes for these novel surgical procedures, especially in a specialized, throwing athlete population [63,64,65].

Posterior Instability

Patients with symptomatic posterior instability who have failed nonoperative measures may be candidates for surgical intervention, typically in form of posterior capsulolabral repair (Figs. 4 and 5). A recent meta-analysis of functional outcomes and return to sport in patients who had undergone arthroscopic stabilization for symptomatic posterior instability included 1153 shoulders overall. They demonstrated return to sport rates of 88% for a cohort of throwing athletes, although return to prior level of performance was only 68%. [66] A study by Mcclincy et al. compared the outcomes of posterior labral repair in a case-matched group of throwing athletes compared to nonthrowing athletes. Overall they found no difference in American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scores, shoulder stability, range of motion or strength between groups. The RTP rate for throwers was 60%, but only 50% in pitchers. [67] A number of other studies have shown that pitchers have a significantly lower rate of RTP after posterior labral repair compared to other position players. [68, 69] A recent long-term clinical outcome study for patients who underwent arthroscopic capsulolabral repair for isolated posterior shoulder instability demonstrated significant improvement in all clinical measures, but only a 35% return to prior level of sport. 28% of patients discontinued their sporting participation due to ongoing shoulder problems. Throwing athletes reported lower preoperative and postoperative outcomes, however, they experienced similar improvements as the rest of the cohort. [70] A separate study investigated risk factors for revision stabilization in a series of 105 throwing athletes who underwent posterior capsulolabral repair. The overall revision rate was 9% and only female sex was found to be associated with a higher risk of failure [71].

MRI of 21 year old baseball player with posterior shoulder pain after swinging a baseball bat. A. Axial MRI image demonstrating reverse Hill-Sachs lesion. B. Axial MRI image demonstrating posterior labral tear. C. Coronal MRI demonstrating humeral head edema consistent with posterior translational event

Multidirectional Instability

Athletes with MDI should only consider operative intervention if they have failed a comprehensive physical therapy program. Given the heterogeneity of MDI, surgery must be individually tailored to meet the needs of the athlete. For years, the relative gold standard for management of MDI has been open capsular shift with or without labral repair in order to stabilize the shoulder. [72] This procedure, however, comes with a high risk of altering the athlete’s native motion and biomechanics. It is also a technically demanding surgery and careful patient counseling is mandatory prior to any operative measure in order to set expectations and maximize patient satisfaction.

Sparse data exist for the outcomes and RTP rates of throwing athletes undergoing surgical management of MDI. Good outcomes have been reported generally with the capsular shift procedure. [73, 74] Longo et al. reported a 7.5% dislocation rate after inferior capsular shift in a systematic review that included 226 patients at 4-year follow up. [75] These were, however, not a select population of athletes or throwers.

Arthroscopic capsular plication procedures have gained popularity for management of MDI patients. These come with the advantage of less invasive, arthroscopic surgery and the ability to adequately address both anterior and posterior capsular laxity. [76,77,78] Studies have shown that arthroscopic techniques can effectively reduce capsular volume and may result in better functional range of motion for patients postoperatively [79], although technical challenges associated with this procedure have limited its widespread adoption. Further studies are needed to determine an optimal surgical approach for MDI patients.

Recommendations

The vast majority of throwing athletes with shoulder instability suffer from microinstability secondary to a series of microtraumas rather than traumatic subluxations or dislocations. Our recommendation is that the majority of these athletes should undergo a rigorous and comprehensive physical therapy program as a first-line treatment. This program should last at least 3–6 months before any surgery is considered. In the event of MDI, at least 6 months of nonoperative treatment is strongly encouraged before any surgical discussion. Therapy should be managed under the supervision of an experienced provider and should focus on restoring motion, core and dynamic stabilizer strength, muscle proprioception and balance. It should seek to reduce an athlete’s pain and eliminate apprehension.

In the case of concurrent rotator cuff injury, significant glenohumeral bone loss or failed nonoperative management, surgical intervention may be considered. We prefer a “less is more” approach to these throwing athletes, performing the minimum surgery necessary to stabilize the shoulder, preferably through an arthroscopic approach. The goal of surgery is to stabilize the shoulder, reduce pain and eliminate apprehension while minimizing the disruption to the athletes’ shoulder biomechanics. In all circumstances, setting appropriate expectations with the athlete and his or her team prior to operating is paramount given the unpredictable results seen with these surgeries.

Conclusions

Management of shoulder instability in throwing athletes remains a diagnostic and treatment challenge. Throwing athletes often suffer from microinstability, where deleterious effects of small microtrauma from chronic repetitive overhead throwing motions lead to subtle biomechanical derangements resulting in arm pain, reduced velocity and impaired performance. These athletes may present with benign physical exams and largely normal MRIs. Anterior instability is most common in throwers due to the abduction and external rotation mechanics seen with throwing, but posterior and multidirectional instability also occur. Regardless of directionality, initial management of these shoulder conditions consists of intensive physical therapy designed to reduce pain, improve range of motion, strength and muscle balance. In cases of failed nonoperative management or where athletes have significant glenohumeral bone loss, stabilization surgery may be indicated. However, care should be taken in these rare circumstances to perform the bare minimum needed to provide shoulder stability, thus avoiding overtightening of the shoulder and maximizing the chances of a full return to previous performance level. Nonetheless, RTP rates after stabilization surgery have mixed results in throwing athletes and proper counseling prior to operative intervention is critical to ensure the best possible outcomes.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Thomas SJ, Swanik CB, Kaminski TW, Higginson JS, Swanik KA, Bartolozzi AR, et al. Humeral retroversion and its association with posterior capsule thickness in collegiate baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):910–6.

Chambers L, Altchek DW. Microinstability and internal impingement in overhead athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2013;32(4):697–707.

Wilk KE, Reinold MM, Andrews JR. The athlete's shoulder. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. 2009. xix, 876 p. p.

Astolfi MM, Struminger AH, Royer TD, Kaminski TW, Swanik CB. Adaptations of the Shoulder to Overhead Throwing in Youth Athletes. J Athl Train. 2015;50(7):726–32.

Edelson G. The development of humeral head retroversion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9(4):316–8.

Braun S, Kokmeyer D, Millett PJ. Shoulder injuries in the throwing athlete. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(4):966–78.

Struhl S. Anterior internal impingement: An arthroscopic observation. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(1):2–7.

Walch G, Boileau P, Noel E, Donell ST. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterosuperior glenoid rim: An arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1992;1(5):238–45.

Jobe FW, Kvitne RS, Giangarra CE. Shoulder pain in the overhand or throwing athlete. The relationship of anterior instability and rotator cuff impingement. Orthop Rev. 1989;18(9):963–75.

Budoff JE, Nirschl RP, Ilahi OA, Rodin DM. Internal impingement in the etiology of rotator cuff tendinosis revisited. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(8):810–4.

Kaplan LD, McMahon PJ, Towers J, Irrgang JJ, Rodosky MW. Internal impingement: findings on magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(7):701–4.

Halbrecht JL, Tirman P, Atkin D. Internal impingement of the shoulder: comparison of findings between the throwing and nonthrowing shoulders of college baseball players. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(3):253–8.

Kirchhoff C, Imhoff AB. Posterosuperior and anterosuperior impingement of the shoulder in overhead athletes-evolving concepts. Int Orthop. 2010;34(7):1049–58.

Funakoshi T, Takahashi T, Shimokobe H, Miyamoto A, Furushima K. Arthroscopic findings of the glenohumeral joint in symptomatic anterior instabilities: comparison between overhead throwing disorders and traumatic shoulder dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32(4):776–85 (Recent study describing common intra-articular pathologies seen with internal impingement in throwing athletes).

Warby SA, Watson L, Ford JJ, Hahne AJ, Pizzari T. Multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint: Etiology, classification, assessment, and management. J Hand Ther. 2017;30(2):175–81.

Arner JW, Provencher MT, Bradley JP, Millett PJ. Evaluation and Management of the Contact Athlete’s Shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30(6):e584–94.

Mlynarek RA, Lee S, Bedi A. Shoulder Injuries in the Overhead Throwing Athlete. Hand Clin. 2017;33(1):19–34.

Meister K. Internal impingement in the shoulder of the overhand athlete: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2000;29(6):433–8.

Foster CR. Multidirectional instability of the shoulder in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1983;2(2):355–68.

Malek S, Reinhold EJ, Pearce GS. The Beighton Score as a measure of generalised joint hypermobility. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(10):1707–16.

Mistry A, Campbell RS. Microinstability and internal impingement of the shoulder. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2015;19(3):277–83.

Bixby EC AC. Anterior Shoulder Instability in the Throwing Athlete. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine. 2021;29. Important article describing common pathology seen with anterior instability in throwing athletes.

Dewing CB, McCormick F, Bell SJ, Solomon DJ, Stanley M, Rooney TB, et al. An analysis of capsular area in patients with anterior, posterior, and multidirectional shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(3):515–22.

Wilbur RR, Shirley MB, Nauert RF, LaPrade MD, Okoroha KR, Krych AJ, et al. Anterior Shoulder Instability in Throwers and Overhead Athletes: Long-term Outcomes in a Geographic Cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(1):182–8 (Matched-cohort analysis comparing outcomes of anterior shoulder instability in overhead and throwing athletes with non-throwing athletes which demonstrated similar outcomes in both groups).

Albertson BS, Trasolini NA, Rue JH, Waterman BR. In-Season Management of Shoulder Instability: How to Evaluate, Treat, and Safely Return to Sport. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2023;16(7):295–305.

Ma R, Brimmo OA, Li X, Colbert L. Current Concepts in Rehabilitation for Traumatic Anterior Shoulder Instability. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10(4):499–506.

Jaggi A, Alexander S. Rehabilitation for Shoulder Instability - Current Approaches. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:957–71.

Aldridge R, Stephen Guffey J, Whitehead MT, Head P. The effects of a daily stretching protocol on passive glenohumeral internal rotation in overhead throwing collegiate athletes. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7(4):365–71.

Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Lee SJ, Mullaney M, McHugh MP. Correction of posterior shoulder tightness is associated with symptom resolution in patients with internal impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):114–9.

Hurley ET, Matache BA, Wong I, Itoi E, Strauss EJ, Delaney RA, et al. Anterior Shoulder Instability Part I-Diagnosis, Nonoperative Management, and Bankart Repair-An International Consensus Statement. Arthroscopy. 2022;38(2):214-23 e7 (International consensus group recommendations on treatment of anterior shoulder instability).

Bateman M, Smith BE, Osborne SE, Wilkes SR. Physiotherapy treatment for atraumatic recurrent shoulder instability: early results of a specific exercise protocol using pathology-specific outcome measures. Shoulder Elbow. 2015;7(4):282–8.

Dickens JF, Owens BD, Cameron KL, Kilcoyne K, Allred CD, Svoboda SJ, et al. Return to play and recurrent instability after in-season anterior shoulder instability: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(12):2842–50.

Buss DD, Lynch GP, Meyer CP, Huber SM, Freehill MQ. Nonoperative management for in-season athletes with anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(6):1430–3.

Hurley ET, Davey MS, Jamal MS, Manjunath AK, Alaia MJ, Strauss EJ. Return-to-Play and Rehabilitation Protocols following Cartilage Restoration Procedures of the Knee: A Systematic Review. Cartilage. 2021;13(1_suppl):907S-14S.

McIntyre K, Belanger A, Dhir J, Somerville L, Watson L, Willis M, et al. Evidence-based conservative rehabilitation for posterior glenohumeral instability: A systematic review. Phys Ther Sport. 2016;22:94–100.

Sheean AJ, Kibler WB, Conway J, Bradley JP. Posterior Labral Injury and Glenohumeral Instability in Overhead Athletes: Current Concepts for Diagnosis and Management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(15):628–37.

Blacknall J, Mackie A, Wallace WA. Patient-reported outcomes following a physiotherapy rehabilitation programme for atraumatic posterior shoulder subluxation. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(2):137–41.

Lee J, Woodmass JM, Bernard CD, Leland DP, Keyt LK, Krych AJ, et al. Nonoperative Management of Posterior Shoulder Instability: What Are the Long-Term Clinical Outcomes? Clin J Sport Med. 2022;32(2):e116–20 (Largest cohort to-date of outcomes of nonoperative management of posterior shoulder instability. Although not specific to throwing athletes, this study supports the efficacy of nonoperative treatment of this condition).

Seroyer ST, Nho SJ, Bach BR Jr, Bush-Joseph CA, Nicholson GP, Romeo AA. Shoulder pain in the overhead throwing athlete. Sports Health. 2009;1(2):108–20.

Watson L, Warby S, Balster S, Lenssen R, Pizzari T. The treatment of multidirectional instability of the shoulder with a rehabilitation program: Part 1. Shoulder Elbow. 2016;8(4):271–8.

Watson L, Warby S, Balster S, Lenssen R, Pizzari T. The treatment of multidirectional instability of the shoulder with a rehabilitation programme: Part 2. Shoulder Elbow. 2017;9(1):46–53.

Burkhead WZ Jr, Rockwood CA Jr. Treatment of instability of the shoulder with an exercise program. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(6):890–6.

Warby SA, Ford JJ, Hahne AJ, Watson L, Balster S, Lenssen R, et al. Comparison of 2 Exercise Rehabilitation Programs for Multidirectional Instability of the Glenohumeral Joint: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(1):87–97 (Important randomized controlled trial of patients with multidirectional instability undergoing two different physical therapy protocols).

Watson L, Balster S, Lenssen R, Hoy G, Pizzari T. The effects of a conservative rehabilitation program for multidirectional instability of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27(1):104–11.

McFarland EG, Neira CA, Gutierrez MI, Cosgarea AJ, Magee M. Clinical significance of the arthroscopic drive-through sign in shoulder surgery. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(1):38–43.

Payne LZ, Altchek DW. The surgical treatment of anterior shoulder instability. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14(4):863–83.

Sonnery-Cottet B, Edwards TB, Noel E, Walch G. Results of arthroscopic treatment of posterosuperior glenoid impingement in tennis players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(2):227–32.

Levitz CL, Dugas J, Andrews JR. The use of arthroscopic thermal capsulorrhaphy to treat internal impingement in baseball players. Arthroscopy. 2001;17(6):573–7.

Jones KJ, Kahlenberg CA, Dodson CC, Nam D, Williams RJ, Altchek DW. Arthroscopic capsular plication for microtraumatic anterior shoulder instability in overhead athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(9):2009–14.

Jobe FW, Giangarra CE, Kvitne RS, Glousman RE. Anterior capsulolabral reconstruction of the shoulder in athletes in overhand sports. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):428–34.

Montgomery WH 3rd, Jobe FW. Functional outcomes in athletes after modified anterior capsulolabral reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(3):352–8.

Funakoshi T, Furushima K, Takahashi T, Miyamoto A, Urata D, Yoshino K, et al. Anterior glenohumeral capsular ligament reconstruction with hamstring autograft for internal impingement with anterior instability of the shoulder in baseball players: preliminary surgical outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(7):1463–73 (This study puts forth a novel technique of hamstring autograft reconstruction of the anterior glenoid labrum in cases of internal impingement in throwing athletes).

Park JY, Lee JH, Oh KS, Chung SW, Lim JJ, Noh YM. Return to play after arthroscopic treatment for shoulder instability in elite and professional baseball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28(1):77–81 (Important study of professional baseball throwers demonstrating good outcomes with arthroscopic labral repair after anterior shoulder dislocation. Patients who had surgery to their nonthrowing shoulder and non-pitchers experienced the best outcomes).

Trinh TQ, Naimark MB, Bedi A, Carpenter JE, Robbins CB, Group MSI, et al. Clinical Outcomes After Anterior Shoulder Stabilization in Overhead Athletes: An Analysis of the MOON Shoulder Instability Consortium. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(6):1404–10. Multicenter study demonstrating good results with arthroscopic labral repair in overhead athletes with low rates of revision surgery. This study suggests, however, that return to play rates may be lower (in some cases less than 50%) for this population.

Harada Y, Iwahori Y, Kajita Y, Takahashi R, Yokoya S, Sumimoto Y, et al. Return to sports after arthroscopic bankart repair on the dominant shoulder in overhead athletes. J Orthop Sci. 2022;27(6):1240–5 (Recent retrospective cohort demonstrating reliable results with arthroscopic labral repair for instability in overhead athletes, however, return to play rates are lower than expected and, in some cases, can take over 13 months).

Schwihla I, Wieser K, Grubhofer F, Zimmermann SM. Long-term recurrence rate in anterior shoulder instability after Bankart repair based on the on- and off-track concept. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023;32(2):269–75.

Garcia GH, Wu HH, Liu JN, Huffman GR, Kelly JDt. Outcomes of the Remplissage Procedure and Its Effects on Return to Sports: Average 5-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(5):1124–30.

Kirac M, Ergun S, Gamli A, Bayram B, Kocaoglu B. Remplissage reduced sense of apprehension and increased the rate of return to sports at preinjury level of elite overhead athletes with on-track anterior shoulder instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2023;31(12):5979–86 (Recently published retrospective cohort challenging prevailing wisdom that the addition of remplissage to arthroscopic labral repair in overhead athletes is detrimental to outcomes and return to play).

Hurley ET, Matache BA, Wong I, Itoi E, Strauss EJ, Delaney RA, et al. Anterior Shoulder Instability Part II-Latarjet, Remplissage, and Glenoid Bone-Grafting-An International Consensus Statement. Arthroscopy. 2022;38(2):224-33 e6.

Bauer S, Neyton L, Collin P, Zumstein M. The open Latarjet-Patte procedure for the treatment of anterior shoulder instability in professional handball players at a mean follow-up of 6.6 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2023. Recent cohort of professional handball players who underwent open Latarjet procedure for anterior instability with bone loss demonstrating good functional and radiographic outcomes with high rates of return to play.

Brzoska R, Laprus H, Malik SS, Solecki W, Juszczak B, Blasiak A. Return to Preinjury-Level Sports After Arthroscopic Latarjet for Recurrent Anterior Shoulder Instability in Professional Athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(5):23259671231166372.

Frantz TL, Everhart JS, Cvetanovich GL, Neviaser A, Jones GL, Hettrich CM, et al. Are Patients Who Undergo the Latarjet Procedure Ready to Return to Play at 6 Months? A Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) Shoulder Group Cohort Study. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(4):923–30.

Boileau P, Baring T, Greco V. Arthroscopic Distal Clavicular Autograft for Congruent Glenoid Reconstruction. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(11):e2389–95.

Robinson SP, Patel V, Rangarajan R, Lee BK, Blout C, Itamura JM. Distal tibia allograft glenoid reconstruction for shoulder instability: outcomes after lesser tuberosity osteotomy. JSES Int. 2021;5(1):60–5.

Frank RM, Romeo AA, Richardson C, Sumner S, Verma NN, Cole BJ, et al. Outcomes of Latarjet Versus Distal Tibia Allograft for Anterior Shoulder Instability Repair: A Matched Cohort Analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(5):1030–8.

Gouveia K, Kay J, Memon M, Simunovic N, Bedi A, Ayeni OR. Return to Sport After Surgical Management of Posterior Shoulder Instability: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2022;50(3):845–57.

McClincy MP, Arner JW, Bradley JP. Posterior Shoulder Instability in Throwing Athletes: A Case-Matched Comparison of Throwers and Non-Throwers. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(6):1041–51.

Radkowski CA, Chhabra A, Baker CL 3rd, Tejwani SG, Bradley JP. Arthroscopic capsulolabral repair for posterior shoulder instability in throwing athletes compared with nonthrowing athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(4):693–9.

Kercher JS, Runner RP, McCarthy TP, Duralde XA. Posterior Labral Repairs of the Shoulder Among Baseball Players: Results and Outcomes With Minimum 2-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(7):1687–93.

Rothrauff BB, Arner JW, Talentino SE, Bradley JP. Minimum 10-Year Clinical Outcomes After Arthroscopic Capsulolabral Repair for Isolated Posterior Shoulder Instability. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(6):1571–80 (Long-term outcomes of arthroscopic labral repair for posterior instability in athletes demonstrating good overall outcomes and durability of repair).

Vaswani R, Arner J, Freiman H, Bradley JP. Risk Factors for Revision Posterior Shoulder Stabilization in Throwing Athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(12):2325967120967652.

Neer CS 2nd, Foster CR. Inferior capsular shift for involuntary inferior and multidirectional instability of the shoulder. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(6):897–908.

Altchek DW, Warren RF, Skyhar MJ, Ortiz G. T-plasty modification of the Bankart procedure for multidirectional instability of the anterior and inferior types. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(1):105–12.

Pollock RG, Owens JM, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. Operative results of the inferior capsular shift procedure for multidirectional instability of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A(7):919–28.

Longo UG, Rizzello G, Loppini M, Locher J, Buchmann S, Maffulli N, et al. Multidirectional Instability of the Shoulder: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(12):2431–43.

Gervasi E, Sebastiani E, Spicuzza A. Multidirectional Shoulder Instability: Arthroscopic Labral Augmentation. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6(1):e219–25.

Housset V, Nourissat G. Arthroscopic Capsular Plication for Multidirectional Shoulder Instability in Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Patients. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10(12):e2767–73.

Caprise PA Jr, Sekiya JK. Open and arthroscopic treatment of multidirectional instability of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(10):1126–31.

Lubiatowski P, Dlugosz J, Slezak M, Ogrodowicz P, Stefaniak J, Walecka J, et al. Effect of arthroscopic techniques on joint volume in shoulder instability: Bankart repair versus capsular shift. Int Orthop. 2017;41(1):149–55.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.T., N.V, and T.K, all wrote main manuscript text. R.T prepared figures 1-5. C.C and J.D were instrumental in manuscript conception and structure. All authors edited and reviewed the final manuscript for critical content. All authors approve of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Competing interests

Ryan Thacher, Nathan Varady and Tyler Khilnani declare they have no conflict of interest Christopher Camp is a paid consultant for Athrex, Inc, provides research support for Major League Baseball and receives royalties from Springer Joshua Dines is a paid consultant for Arthrex, Inc, owns stock in ViewFi, and receives royalties from Wolters Kluwer Health-Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Thieme, Linvatec and Arthrex Inc.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Thacher, R.R., Varady, N.H., Khilnani, T. et al. Current Concepts on the Management of Shoulder Instability in Throwing Athletes. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 17, 353–364 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-024-09910-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-024-09910-1