Abstract

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death for women in the USA. While it is clear that gender-specific differences in presentation, pathophysiology, and outcomes exist among men and women presenting with acute coronary syndromes (ACS), efforts to better understand and to improve recognition and outcomes for women with ACS continue. Past studies have shown differences in age, presentation, comorbidities, extent of disease, management, and outcomes for women presenting with ACS compared with men. This review will highlight these differences and provide current knowledge regarding potential mechanisms underlying the observed differences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in women in the USA [1]. There are well-documented differences in the epidemiology, presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) between women and men. Some of these differences may be related to sex-specific pathophysiology and anatomy that differ from the pattern of focal obstructive coronary disease and plaque rupture typically observed in men with ACS [2]. In contrast, women presenting with similar symptoms typically have much less obstructive disease and may more commonly have plaque disruption or erosion with subsequent thrombus formation, as well as microvascular and endothelial dysfunction [3, 4, 5•]. Prior studies have revealed delays in identification and treatment of women presenting with ACS and a higher risk of complications from percutaneous as well as surgical interventions. While women with non-obstructive coronary heart disease (CHD) have better outcomes than those with significant obstructive coronary disease, they still suffer from significant morbidity and mortality related to CHD, as compared to women without CHD [6••, 7].

Epidemiology

More women than men die due to CHD annually [8]. In 2010 there were 6,250,000 patients with a discharge diagnosis of ACS in the USA; 2,620,000 of those were women [8]. The average age for a first myocardial infarction is 64.9 years for men and 72.3 years for women, and the incidence of CHD in women trails behind men by 10 years, although this gap narrows with each decade [8, 9]. At initial presentation for ACS, women tend to be older, have more comorbidities (including hypertension, diabetes, congestive heart failure (CHF), and chronic kidney disease), and are less likely to have had a prior myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), or percutaneous intervention (PCI) than men [9–15].

Younger women represent a unique and especially high-risk subset, with more than 30,000 women in this demographic hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the USA each year [16••, 17]. Gupta et al examined a national sample of patients between 30 and 54 years of age presenting with AMI between 2001 and 2010 and found that, compared to older women, women <55 years of age were more likely to be obese and smokers and more commonly had comorbidities such as CHF, hypertension (HTN), and diabetes, when compared with age-matched men. Younger women also had longer hospital stays and higher in-hospital mortality compared with young men [16••]. They also found that younger patients, both men and women, were not experiencing an overall reduction in hospitalization rates for AMI, as compared with older patients. This finding may highlight the role that genetic predisposition plays in young people who present with ACS, but it also points toward the need to more aggressively identify and treat cardiac risk factors in younger patients. A more recent study examined outcomes in women <55 years of age presenting with ACS at a single center, and similarly showed increased comorbidities (obesity, smoking, diabetes, and HTN) in those subjects. However, this study also found that while young women had the lowest mortality at 6 months, they had a higher rehospitalization rate [18••].

A recent study of women veterans undergoing cardiac catheterization has identified a potentially unique subset of women presenting with chest pain. Similar to other studies, women undergoing catheterization were younger, had less obstructive coronary artery disease on coronary angiography, and had similar long-term outcomes as compared with men veterans. In the subgroup of veterans presenting with ACS, there were similar rates of single-vessel disease but higher rates of non-obstructive and normal coronary arteries in women versus men. However, in contrast to previous studies that showed a higher incidence of smoking, HTN, diabetes, and CHF in women compared with men, women veterans had fewer traditional cardiac risk factors but more depression, obesity, and post-traumatic stress disorder, when compared with their male counterparts [19••]. These findings suggest that in women veterans, mental health conditions may be playing a role in their chest pain presentation, both because these conditions are contributing to non-cardiac chest pain and because conditions such as PTSD have been linked to increased risk for subsequent development of CHD, potentially due to prolonged sympathetic activation leading to cardiac autonomic dysfunction [20, 21]. Women veterans may also more commonly present with chest pain and ACS due to microvascular disease and endothelial dysfunction, discussed in greater depth below [22, 23, 24•].

Presentation

A multitude of studies have examined presenting symptoms in ACS in men as compared with women, with conflicting results. Older studies revealed a tendency toward more atypical presentations in women, with less chest pain and a higher incidence of jaw pain, neck pain, back pain, nausea, and emesis [25–27]. However, most investigators have found that chest pain remains the most common presentation for ACS in women as well as in men and that some of the other potential differences in presentation could be explained by age and comorbidities and are not predicted by gender [25, 28•].

It has been well documented that women are slower to present for evaluation and therefore have longer ischemic times and more delay from symptom onset to diagnosis and treatment, compared with men [29–31]. Differences in presenting symptoms were once thought to potentially account for this, but since chest pain remains the most common initial symptom in women as well as in men, other factors must be considered to account for delayed presentation, including patient awareness, potential physician bias, and perceived gender roles and socioeconomic issues. Survey data from the AHA has shown that among women, awareness of heart disease as their leading cause of death increased from 30 % in 1997 to 56 % in 2012—still just over half of all women [8]. Additionally, awareness of heart attack warning signs and symptoms remains poor among women, with 56 % identifying chest, neck, shoulder, and arm pain; 38 % citing shortness of breath; 17 % chest tightness; 18 % nausea; and only 10 % identifying fatigue as a potential warning sign [8]. Physician perceptions may also play a role in delays to diagnosis and initiation of treatment. It is well known that women present with first myocardial infarction on average 10 years later than men, which may lead to an initial lower pretest probability in the mind of physicians who are evaluating a woman presenting with chest discomfort. This potential prejudice was corroborated by a 2004 study which revealed that fewer than one in five physicians were aware of the fact that the annual number of deaths from cardiovascular disease among women exceeded that of men [8].

Management

Interventional Strategies

In women presenting with ACS, studies have shown benefit for an early invasive strategy especially in the subset of women defined as high risk [32]. A meta-analysis from 2008 looked at 3075 women and 7075 men presenting with unstable angina or non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and compared outcomes from an early invasive strategy versus a conservative strategy. Equal benefit was found with an early invasive strategy for the composite end point of death, MI, or rehospitalization with ACS for men and high-risk (biomarker positive) women. However, this benefit was not sustained in low risk (biomarker negative) women, suggesting that a conservative strategy may be more appropriate in that subset of patients [32]. If a focal obstructive lesion is found at the time of angiography, several studies have shown substantial benefit for drug-eluting stents (DES) over bare metal stents (BMS) in women [33, 34••]. Stefanini et al. looked at 11,557 female patients from 26 randomized trials comparing outcomes according to stent type. At 3-year follow-up, they found that women treated with newer generation DES had a significantly lower rate of death or myocardial infarction, as well as a better safety profile with less stent thrombosis and significantly lower rates of target lesion revascularization [34••].

Women tend to undergo fewer interventional procedures when presenting with ACS than men; those that do undergo angioplasty or percutaneous intervention have been shown to have worse outcomes than their male counterparts, including increased mortality and major cardiovascular adverse events (MACE) [11, 35–38]. This finding has generally been attributed to the advanced age of women at presentation, greater number of comorbidities including HTN and CHF, and smaller body size. However, more recent data may reveal that the gender gap in adverse event rates surrounding intervention has narrowed or disappeared with contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) strategies. A recent meta-analysis of 35 studies comprising 18,555 women presenting with ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated with percutaneous intervention initially showed increased in-hospital and all-cause 1-year mortality in women compared with men; this difference was no longer significant after adjustment for baseline cardiovascular risk factors and differences in presentation (i.e., time to initial treatment, response by medical infrastructure, and health care utilization) [39••]. Other studies have also confirmed the finding that there is no difference in MACE or death after adjustment for baseline characteristics [10, 15, 40].

While this is reassuring for women undergoing PCI, studies continue to show increased peri-procedural complications for women, specifically surrounding bleeding and vascular complications. Data collected from 2002 to 2003 looking at 22,725 (34.7 % women) patients undergoing PCI across Michigan revealed similar rates of PCI between women and men and no difference in mortality or MACE after adjustment for baseline renal function and body surface area (BSA). However, there were three times as many vascular complications; more contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN); twice as many transfusions; and a higher likelihood of gastrointestinal bleeding, infection, stroke, or TIA in women as compared with men [15]. The finding that mortality is no different but that important gender differences in vascular complications and bleeding remain has been supported by several other studies [11, 41, 42].

Two key factors, kidney disease and small body size, have been identified by multiple studies as the likely reasons for these observed differences [15, 43–47]. Despite less aggressive anticoagulation regimens and weight-based heparin dosing, an increased risk remains in women. Current guidelines from the ACC conclude that despite differences in peri-procedural outcomes between men and women undergoing PCI, evidence still favors using the same procedures and protocols in men and women [48]. Future research examining the effect of medication dosing based on creatinine clearance (CrCl) versus creatinine and BSA as well as consideration of smaller catheters and devices in women may lead to improvements in the quality of care and reduction in these continuing gender disparities in PCI outcomes.

Pharmacologic Strategies

Women have been underrepresented in many pharmacotherapy trials, a fact that limits our ability to explore gender-related differences in outcomes and efficacy of medical therapy. Despite this, available data have shown likely equal benefit in both sexes for most guideline-based medications. Therefore, current guidelines for the medical management of ACS recommend that the same evidence-based medications should be utilized in men and women, including aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) if indicated, and high-dose statin therapy [9, 49, 50].

Studies are conflicting regarding whether women are treated less aggressively than men, including the question of whether they receive less evidence-based medications on discharge from the hospital following ACS [10, 18••, 37, 38, 51–59]. Several studies have shown that women are less likely to receive evidence-based medical therapy following admission for ACS; postulated reasons include poor recognition and treatment of CHD in women, fear of increased side effects from medications, patient preference, higher incidence of conservative treatment without intervention, or simply that more women are found to have normal coronary arteries or non-obstructive disease at angiography and thus are not offered secondary prevention strategies.

Lifestyle Interventions

Despite the known benefits of cardiac rehabilitation post-ACS, with decreased mortality, lower rates of recurrent MI, and improved quality of life, various studies have found that women are less likely to participate than men. Witt et al. examined 1821 patients with incident MI (42 % women) and found that women were 55 % less likely to participate than men and that participation decreased with increasing age [60]. A Medicare study also revealed that older individuals, women, non-Whites, and patients with increased comorbidities were significantly less likely to receive cardiac rehabilitation. The type of revascularization, household income, level of education, and proximity of the rehabilitation facility were all important predictors of participation [61]. Further research into barriers to participation, including reasons that may be specific to women, is needed, as secondary prevention is indisputably a vital part of treatment for these patients.

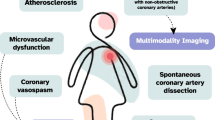

Prevalence and Pathophysiology of Non-obstructive CHD

One of the most striking gender differences in ACS is that women have far less obstructive CHD than men at coronary angiography [9, 11, 15, 62–64]. This has been shown in many studies, including the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS), which showed that approximately 50 % of women undergoing cardiac catheterization for chest pain did not have significant obstructive CHD [2]. This finding continues to hold true when looking at women presenting with ACS. A 2005 study of women presenting with ACS found that women were twice as likely to have non-obstructive CHD as men [63]. Similarly, a study from our institution looking at 1734 patients presenting with ACS demonstrated similar rates of NSTEMI and STEMI among men and women but found that women were significantly more likely to have normal or non-obstructive CAD as compared with men (43 vs 31 %; p < 0.0001) [65].

The substantially lower amount of obstructive disease in women presenting with chest pain has led to alternate explanations for chest pain syndromes in women, including microvascular ischemia, endothelial dysfunction, and altered vasomotor tone. It may also be that women do not manifest coronary disease as focal obstructive stenoses but rather develop more diffuse disease that is not amenable to PCI. The effect of sex hormones on vasculature may also play a role in the gender-related differences observed in CHD. Estrogens are known to have cardioprotective effects, stimulating the release of endothelium-derived growth factor, inhibiting the renin-angiotensin system, and promoting a direct vasodilatory effect on the vasculature [66, 67]. This may explain the absence of more focal coronary disease and the higher prevalence of subclinical or diffuse coronary disease in women compared to men. Despite this, large trials including Heart and Estrogen/Progesterone Replacement Study (HERS), Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), and the Raloxifene Use for the Heart Trial (RUTH) all showed no reduction in cardiovascular events with hormone replacement therapy or hormone alternatives [68–70].

The Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) explored the above hypotheses and found that 29 % of women with normal or non-obstructive CHD at the time of cardiac catheterization performed for ACS had abnormal myocardial perfusion studies, and up to 47 % of women had impaired coronary vascular reactivity using positron emission tomography (PET), invasive Doppler flow wire, or P-31 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy [3]. More recently, Reynolds et al. examined women presenting with myocardial infarction and found that <50 % had angiographic stenoses at the time of catheterization, using intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR). They found evidence of plaque disruption in 38 % of patients using IVUS and abnormal CMR in 59 % of patients, with an ischemic pattern being the most common finding [4]. Another recent study of 139 patients (77 % women) with angina and non-obstructive CAD (<50 %) who were evaluated for alternative causes of ischemia found that all patients had some degree of atherosclerosis on IVUS imaging, 44 % had evidence of endothelial dysfunction, 21 % had microvascular dysfunction, and 5 % had abnormal fractional flow reserve [5•]. It may be that outward remodeling and plaque disruption, erosion, or embolization is a more common mechanism for ischemia in women. Lastly, other diagnoses that can mimic ACS resulting from CHD must be entertained and may be more common in women; these conditions include Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, spontaneous coronary dissection, and vasospastic or variant angina [71, 72].

Outcomes in ACS with Non-obstructive CAD

It is important to identify this subset of patients, who are predominately female, presenting with ACS and normal coronary arteries or non-obstructive disease at angiography, as they do have significant long-term morbidity and mortality. As discussed above, there are a variety of potential explanations for the underlying pathophysiology, which likely differs significantly from those presenting with focal epicardial coronary obstruction, and may include plaque erosion or disruption, embolization, diffuse atherosclerosis not amenable to PCI, and microvascular and/or endothelial dysfunction. De Ferrari and colleagues looked at 8 randomized trials of a combined 37,101 patients presenting with NSTEMI and found that 1 in10 had non-obstructive coronary disease. While this group had lower 30-day death or MI rates compared to those patients with obstructive disease (13.3 %), the percentage was not insignificant at 2.2 % [6••]. In the WISE study of women with suspected ischemia found to have non-obstructive CAD, 5-year cardiovascular event rates were 16 % among those with non-obstructive CAD (<50 % stenosis) and 7.9 % among women with normal coronary arteries at angiogram, compared to a rate of 2.4 % in the control group [7].

Studies examining patients with known microvascular or endothelial dysfunction have shown that these patients also have poor outcomes as compared to the general population, with increased rates of death and MI and other adverse cardiac events including ongoing symptoms, rehospitalization, heart failure, and considerable ongoing costs to the health care system [3, 4, 7, 62, 73–81].

Due to the poor outcomes in this population, it is unfortunate that many times reassurance is provided and symptoms are dismissed when non-obstructive or normal coronary arteries are found at catheterization, and no further treatment or secondary prevention is subsequently offered. It is vital that future studies focus on a better understanding of the pathophysiology of women presenting with ACS symptoms who are found to have non-obstructive disease, including a more uniform way to identify this population, increased awareness among medical providers of the potential for adverse outcomes in this population, and specific treatment strategies aimed at improving outcomes as well as quality of life.

Microvascular Disease and Endothelial Dysfunction

This population represents both a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge; a diagnosis of microvascular disease or endothelial dysfunction needs to be entertained in patients presenting with anginal chest pain, at least one cardiac risk factor, an abnormal functional study, and normal coronary arteries or minimal disease on angiography. Generally, this set of diagnoses is arrived at by exclusion; it is rarely routinely confirmed with the use of coronary flow reserve (CFR) measurement during cardiac catheterization or through non-invasive assessment of CFR using PET imaging. CFR is defined as the ratio of maximal hyperemic coronary blood flow, generally measured after exposure to a vasodilator such as adenosine, to resting blood flow. Normal values range from 2.5 to 5; several studies have linked reduced CFR to an increased risk of MACE [73]. Similarly, endothelial dysfunction can be evaluated by infusion of intracoronary acetylcholine with an abnormal response showing vasoconstriction. Cohorts of patients with abnormal endothelial dysfunction but minimal or no coronary artery disease have been followed and have been shown to have significantly higher hard cardiac event rates [82].

A more standardized approach to diagnosis and treatment, including routine evaluation of CFR and endothelial dysfunction, may be warranted. The first phase of the iPOWER study, published in 2014, looked at the feasibility of routine assessment of microvascular dysfunction in women presenting with angina and found to have non-obstructive coronary disease. The investigators assessed CFR using transthoracic echo-guided Doppler assessment of the left anterior descending artery before and during infusion of a vasodilator. They found that this novel non-invasive method of assessing CFR was feasible for the routine assessment of microvascular disease [83••]. Further phases of the study will evaluate other modalities for detecting microvascular dysfunction, including PET, MRI, and CT. Finally, randomized studies of medical interventions in patients identified as having microvascular dysfunction will be performed; these future studies will hopefully provide a wealth of information to improve the treatment of this patient population [83••]. Currently, several treatment strategies including exercise, beta-blockers, ACEi, ranolazine, and statins have all shown some benefit in this population, with improvements shown in reduction of angina, quality of life, and exercise tolerance [84–90]. Further studies are needed to determine whether specific therapies are associated with improved long-term outcomes such as survival as well as symptomatic improvement.

Conclusions

Women presenting with ACS tend to be older and have more preexisting comorbidities. There are important gender differences in the pathophysiology of CHD that may be linked to differences in hormonal milieu. Women also have significantly less obstructive coronary artery disease at the time of angiography. Better diagnostic strategies are needed in order to delineate whether microvascular disease or endothelial dysfunction is to blame for chest pain presentation in some women. Despite the lower rate of obstructive epicardial coronary disease, women experience more adverse outcomes than men, including more persistent symptoms, increased need for repeat hospitalizations, and more adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Further studies are needed to more clearly elucidate the unique pathophysiology of CAD in women and to better determine why women more frequently experience chest pain in the absence of obstructive epicardial coronary disease.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4):1–117.

Kennedy JW et al. The clinical spectrum of coronary artery disease and its surgical and medical management, 1974–1979. The Coronary Artery Surgery Study. Circulation. 1982;66(5 Pt 2):III16–23.

Bairey Merz N et al. Women’s ischemic syndrome evaluation: current status and future research directions: report of the national heart, lung and blood institute workshop: October 2–4, 2002: executive summary. Circulation. 2004;109(6):805–7.

Reynolds HR et al. Mechanisms of myocardial infarction in women without angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124(13):1414–25.

Lee BK et al. Invasive evaluation of patients with angina in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2015;131(12):1054–60. This study revealed that a substantial number of patients presenting with angina without evidence of obstructive coronary disease still have evidence of occult coronary abnormalities including atherosclerosis by IVUS, endothelial dysfunction, microvascular impairment, or abnormal fractional flow reserve on invasive evaluation.

De Ferrari GM et al. Outcomes among non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes patients with no angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease: observations from 37,101 patients. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2014;3(1):37–45. This study examined outcomes in patients presenting with NSTEMI found to have non-obstructive CAD. They found that the population was younger, more likely to be female, and less likely to have a history of previous MI or revascularization. However, they found that rates of 30-day death or MI, although lower than those with obstructive CAD, were not insignificant at 2.2%, highlighting the need for a better understanding of this unique patient population and specific management strategies for this group.

Gulati M et al. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes in women with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: a report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study and the St James Women Take Heart Project. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(9):843–50.

Go AS et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–292.

Duvernoy CS. Coronary heart disease in women: what do we know now? Future Cardiol. 2005;1(5):617–28.

Lin CF et al. Sex differences in the treatment and outcome of patients with acute coronary syndrome after percutaneous coronary intervention: a population-based study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2014;23(3):238–45.

Hochman JS et al. Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(4):226–32.

Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(20):2043–50.

Lansky AJ et al. Gender and the extent of coronary atherosclerosis, plaque composition, and clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5(3 Suppl):S62–72.

Cowie CC et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):287–94.

Duvernoy CS et al. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) percutaneous coronary intervention registry. Am Heart J. 2010;159(4):677–83. e1.

Gupta A et al. Trends in acute myocardial infarction in young patients and differences by sex and race, 2001 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(4):337–45. This study revealed that younger women presenting with ACS may represent a particularly high risk group with more comorbidities, longer hospitalizations, and higher in-hospital mortality compared to young men.

Towfighi A, Markovic D, Ovbiagele B. National gender-specific trends in myocardial infarction hospitalization rates among patients aged 35 to 64 years. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(8):1102–7.

Davis M et al. Acute coronary syndrome in young women under 55 years of age: clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00392-015-0827-2 .This study showed that young women, <55 years of age, presenting with ACS had more comorbidities than older women, underwent less invasive evaluation, and were less likely to receive evidence based medical therapy. This study highlights the need to aggressively screen for and treat modifiable risk factors in this population.

Davis MB et al. Characteristics and outcomes of women veterans undergoing cardiac catheterization in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System: insights from the VA CART Program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(2 Suppl 1):S39–47. This study revealed a unique subset of women, veterans, presenting with angina who are more likely to have non-traditional cardiac risk factors including obesity, depression, and PTSD. These women had less obstructive CAD at catheterization and lower 1-year mortality as well as re-hospitalization rates, suggesting a potential alternate etiology for their angina.

Kubzansky LD et al. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in the normative aging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):109–16.

Tan G et al. Associations among pain, PTSD, mTBI, and heart rate variability in veterans of operation enduring and Iraqi freedom: a pilot study. Pain Med. 2009;10(7):1237–45.

Ho KY et al. Non-cardiac, non-oesophageal chest pain: the relevance of psychological factors. Gut. 1998;43(1):105–10.

Rasul F et al. Common mental disorder and physical illness in the Renfrew and Paisley (MIDSPAN) study. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(6):1163–70.

Christoph M et al. Mental symptoms in patients with cardiac symptoms and normal coronary arteries. Open Heart. 2014;1(1):e000093. This study revealed that in patients with cardiac symptoms and normal coronary arteries at catheterization, there is a much higher prevalence of mental health symptoms.

Arslanian-Engoren C et al. Symptoms of men and women presenting with acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(9):1177–81.

Milner KA et al. Gender and age differences in chief complaints of acute myocardial infarction (Worcester Heart Attack Study). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93(5):606–8.

Meshack AF et al. Comparison of reported symptoms of acute myocardial infarction in Mexican Americans versus non-Hispanic whites (the Corpus Christi Heart Project). Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(11):1329–32.

Kreatsoulas C et al. Reconstructing angina: cardiac symptoms are the same in women and men. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(9):829–31. This study looked at symptom descriptors of patients with cardiac symptoms undergoing their first catheterization, and found no significant difference in symptom descriptions between women and men, with the most common descriptors for both sexes being chest pain, pressure, or tightness.

Gibler WB et al. Persistence of delays in presentation and treatment for patients with acute myocardial infarction: the GUSTO-I and GUSTO-III experience. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(2):123–30.

Dracup K, Moser DK. Beyond sociodemographics: factors influencing the decision to seek treatment for symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 1997;26(4):253–62.

Yarzebski J et al. Gender differences and factors associated with the receipt of thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a community-wide perspective. Am Heart J. 1996;131(1):43–50.

O’Donoghue M et al. Early invasive vs conservative treatment strategies in women and men with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300(1):71–80.

Kornowski R et al. A comparative analysis of major clinical outcomes with drug-eluting stents versus bare metal stents in male versus female patients. EuroIntervention. 2012;7(9):1051–9.

Stefanini GG et al. Safety and efficacy of drug-eluting stents in women: a patient-level pooled analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2013;382(9908):1879–88. This meta-analysis looked at 11,557 women undergoing percutaneous intervention to determine the safety and efficacy of DES. They found that the use of DES resulted in lower rate of death or MI as well as a better safety profile and lower rates of target lesion revascularization compared to older generation DES or BMS.

Malenka DJ et al. Differences in outcomes between women and men associated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. A regional prospective study of 13,061 procedures. Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Circulation. 1996;94(9 Suppl):II99–104.

Mehilli J et al. Differences in prognostic factors and outcomes between women and men undergoing coronary artery stenting. JAMA. 2000;284(14):1799–805.

Daly C et al. Gender differences in the management and clinical outcome of stable angina. Circulation. 2006;113(4):490–8.

Hvelplund A et al. Women with acute coronary syndrome are less invasively examined and subsequently less treated than men. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(6):684–90.

Pancholy SB et al. Sex differences in short-term and long-term all-cause mortality among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous intervention: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1822–30. This meta-analysis examined differences in mortality by sex of patients presenting with STEMI. They found that after adjustment for baseline cardiovascular risk factors, there was no significant difference in 1-year mortality between men and women, arguing against the previously held thought that women have higher mortality than men.

Iakovou I et al. Gender differences in clinical outcome after coronary artery stenting with use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89(8):976–9.

Ashby DT et al. Comparison of outcomes in men versus women having percutaneous coronary interventions in small coronary arteries. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(8):979.

Peterson ED et al. Effect of gender on the outcomes of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(4):359–64.

Latif F et al. In-hospital and 1-year outcomes among percutaneous coronary intervention patients with chronic kidney disease in the era of drug-eluting stents: a report from the EVENT (Evaluation of Drug Eluting Stents and Ischemic Events) registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(1):37–45.

Rubenstein MH et al. Are patients with renal failure good candidates for percutaneous coronary revascularization in the new device era? Circulation. 2000;102(24):2966–72.

Best PJ et al. The impact of renal insufficiency on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(7):1113–9.

Kahn JK et al. Short- and long-term outcome of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty in chronic dialysis patients. Am Heart J. 1990;119(3 Pt 1):484–9.

Lansky AJ et al. Gender differences in outcomes after primary angioplasty versus primary stenting with and without abciximab for acute myocardial infarction: results of the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) trial. Circulation. 2005;111(13):1611–8.

Lansky AJ et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention and adjunctive pharmacotherapy in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;111(7):940–53.

Antman EM et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction; a report of the American college of cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(3):E1–211.

Amsterdam EA et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(24):e139–228.

Shaw LJ et al. Gender differences in the noninvasive evaluation and management of patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(7):559–66.

Mark DB et al. Absence of sex bias in the referral of patients for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(16):1101–6.

Roeters van Lennep JE et al. Gender differences in diagnosis and treatment of coronary artery disease from 1981 to 1997. No evidence for the Yentl syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2000;21(11):911–8.

Bowker TJ et al. A national Survey of Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischaemia (SAMII) in the U.K.: characteristics, management and in-hospital outcome in women compared to men in patients under 70 years. Eur Heart J. 2000;21(17):1458–63.

Blomkalns AL et al. Gender disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: large-scale observations from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines) National Quality Improvement Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(6):832–7.

Alfredsson J et al. Gender differences in management and outcome in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2007;93(11):1357–62.

Shehab A et al. Gender disparities in the presentation, management and outcomes of acute coronary syndrome patients: data from the 2nd Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events (Gulf RACE-2). PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55508.

Shehab A et al. Gender differences in acute coronary syndrome in Arab Emirati women–implications for clinical management. Angiology. 2013;64(1):9–14.

Song XT et al. Gender based differences in patients with acute coronary syndrome: findings from Chinese Registry of Acute Coronary Events (CRACE). Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120(12):1063–7.

Witt BJ et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction in the community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44(5):988–96.

Suaya JA et al. Use of cardiac rehabilitation by Medicare beneficiaries after myocardial infarction or coronary bypass surgery. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1653–62.

Jespersen L et al. Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(6):734–44.

Bugiardini R, Bairey Merz CN. Angina with “normal” coronary arteries: a changing philosophy. JAMA. 2005;293(4):477–84.

Berger JS et al. Sex differences in mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302(8):874–82.

Dey S et al. Treatment bias against women with acute coronary syndrome: fact or fantasy? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(5):276A–7.

dos Santos RL et al. Sex hormones in the cardiovascular system. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2014;18(2):89–103.

Orshal JM, Khalil RA. Gender, sex hormones, and vascular tone. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286(2):R233–49.

Hulley S et al. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280(7):605–13.

Manson JE et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(6):523–34.

Barrett-Connor E et al. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(2):125–37.

Reynolds HR. Myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary artery disease. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2012;27(6):655–60.

Mortensen KH et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: a Western Denmark Heart Registry study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74(5):710–7.

Pepine CJ et al. Coronary microvascular reactivity to adenosine predicts adverse outcome in women evaluated for suspected ischemia results from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute WISE (Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(25):2825–32.

Murthy VL et al. Improved cardiac risk assessment with noninvasive measures of coronary flow reserve. Circulation. 2011;124(20):2215–24.

Britten MB, Zeiher AM, Schachinger V. Microvascular dysfunction in angiographically normal or mildly diseased coronary arteries predicts adverse cardiovascular long-term outcome. Coron Artery Dis. 2004;15(5):259–64.

Herzog BA et al. Long-term prognostic value of 13N-ammonia myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography added value of coronary flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(2):150–6.

Fukushima K et al. Prediction of short-term cardiovascular events using quantification of global myocardial flow reserve in patients referred for clinical 82Rb PET perfusion imaging. J Nucl Med. 2011;52(5):726–32.

Johnson BD et al. Prognosis in women with myocardial ischemia in the absence of obstructive coronary disease: results from the National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Circulation. 2004;109(24):2993–9.

Shaw LJ et al. The economic burden of angina in women with suspected ischemic heart disease: results from the National Institutes of Health–National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation. 2006;114(9):894–904.

Ong P et al. High prevalence of a pathological response to acetylcholine testing in patients with stable angina pectoris and unobstructed coronary arteries. The ACOVA Study (Abnormal COronary VAsomotion in patients with stable angina and unobstructed coronary arteries). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(7):655–62.

Humphries KH et al. Angina with “normal” coronary arteries: sex differences in outcomes. Am Heart J. 2008;155(2):375–81.

Suwaidi JA et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with mild coronary artery disease and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation. 2000;101(9):948–54.

Prescott E et al. Improving diagnosis and treatment of women with angina pectoris and microvascular disease: the iPOWER study design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2014;167(4):452–8. This study revealed that routine non-invasive assessment of coronary flow reserve with TTE is feasible and could lead to better identification and treatment of patients with microvascular ischemia.

Bugiardini R et al. Comparison of verapamil versus propranolol therapy in syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 1989;63(5):286–90.

Lanza GA et al. Atenolol versus amlodipine versus isosorbide-5-mononitrate on anginal symptoms in syndrome X. Am J Cardiol. 1999;84(7):854–6.

Pauly DF et al. In women with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, nonobstructive coronary arteries, and microvascular dysfunction, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition is associated with improved microvascular function: a double-blind randomized study from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Am Heart J. 2011;162(4):678–84.

Treasure CB et al. Beneficial effects of cholesterol-lowering therapy on the coronary endothelium in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(8):481–7.

Kayikcioglu M et al. Benefits of statin treatment in cardiac syndrome-X1. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(22):1999–2005.

Eriksson BE et al. Physical training in syndrome X: physical training counteracts deconditioning and pain in syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(5):1619–25.

Duvernoy CS. Evolving strategies for the treatment of microvascular angina in women. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10(11):1413–9.

Compliance with Ethics and Guidelines

Conflicts of Interest

Ashley M. Funk and Claire S. Duvernoy declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Women + Heart Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Funk, A.M., Duvernoy, C.S. Acute Coronary Syndrome: Current Diagnosis and Management in Women. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 9, 39 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-015-0468-z

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-015-0468-z