Abstract

Upward comparisons, a psychological process in which individuals compare themselves to perceived superiors, have gained prominence in the workplace. Nevertheless, their impact on employees’ sequent behaviors has yielded inconsistent results. To address these discrepancies, this study draws upon social comparison theory to investigate the conditions under which workplace upward comparisons exert a double-edged sword effect on employees’ subsequent behavior. Through a multi-wave, multi-source survey involving 282 employees and 65 leaders from 65 teams, our findings reveal that when employees perceive overall justice as high, workplace upward comparisons tend to evoke benign envy, leading to constructive self-improvement behaviors. However, when employees perceive overall justice as low, workplace upward comparisons are more likely to trigger malicious envy, resulting in instigated incivility. Our study advances a thorough understanding of when and how workplace upward comparisons may lead to disparate behavioral responses by eliciting two distinct forms of envy. The theoretical and practical implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the workplace, employees commonly engage in comparisons with their colleagues concerning various aspects, such as salary, performance with supervisors (Brown et al., 2007; Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019; Pan et al., 2021). These social comparisons serve as a means for employees to evaluate their current standing and future prospects within the organization (Hu & Liden, 2013; Yu et al., 2018). While social comparisons may involve peers of both inferiors and superiors, our focus is on comparisons with those who are viewed as superior, i.e., workplace upward comparisons (Brown et al., 2007; Watkins, 2021), which are more prevalent and more likely to elicit stronger emotional and behavioral responses (Buunk & Gibbons, 2007; Koopman et al., 2020). Comprehending the consequences of workplace upward comparisons is crucial due to its profound implications for work-related outcomes, such as team functioning and organizational effectiveness (see Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019 for a review).

Acknowledging this phenomenon, an extensive body of literature delves into a singular and specific dimension of upward social comparisons, such as performance, leader-member exchange, exploring its influence on employees’ subsequent responses (e.g., Campbell et al., 2017; Downes et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022). However, interactions among colleagues are multifaceted (Chiaburu & Harrison, 2008; Pan et al., 2021), and employees’ upward comparisons are more likely to encompass comprehensive aspects rather than a specific one (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019). While prior research has offered valuable insights into the effects of singular and specific upward comparisons, understanding how employees respond to such holistic workplace upward comparisons remains much-needed but limited in the literature (Gong & Zhang, 2020).

Existing research has identified contradictory individual coping responses elicited by workplace upward comparisons (Diel et al., 2021; Koopman et al., 2020). One way is that upward comparisons can frustrate individuals, potentially triggering destructive behaviors (e.g., social undermining) in an attempt to disrupt superiors (e.g., Koopman et al., 2020; Reh et al., 2018). However, recent studies also conceptualized workplace upward comparisons as motivational forces, prompting constructive behaviors (e.g., increased effort) to attain superiors’ success level (Diel et al., 2021; Smith, 2000). Given these inconsistent findings, it is crucial to adopt a contingency perspective to investigate the boundary conditions, which differentiate the impacts of general workplace upward comparisons on employees’ subsequent emotional and behavioral responses, moving beyond the monolithic “either-good-or-bad” research paradigm.

Social comparison theory has underscored the significance of individuals’ cognitive evaluations of their coworkers’ achievements in determining their positive or negative reactions (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019; Smith, 2000). Further, prior research has also consistently demonstrated that individuals may draw on cognitive judgments of the overall justice within the organization while forming a comprehensive evaluation of an entity (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009; Colquitt & Shaw, 2005). This is the case in our thorough exploration into the contingent consequences of general workplace upward comparisons. Accordingly, we draw on the justice literature and propose that employees’ response to workplace upward comparisons is a function of their overall justice perception, which refers to an individual’s holistic assessment of the fairness of their experiences within the workplace (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009). In line with social comparison theory, workplace upward comparisons under different conditions of overall justice perception can trigger divergent emotional responses (i.e., assimilative or contrastive), which further motivate individuals to behave in an attempt to either elevate themselves or pull down these targets (Festinger, 1954).

Envy, as the most typical emotional response to upward comparisons (Duffy et al., 2012), involves two distinct forms: benign envy, characterized as an assimilative emotion, and malicious envy, characterized as a contrastive emotion (Lange & Crusius, 2015a). Despite dual envy encompassing discomfort, they differ in nature and are associated with different behavioral reactions (Van de Ven et al., 2009). Specifically, when overall justice perception is high, employees perceive the achievements of superiors as deserved. This perception fosters benign envy and motivates employees to strive for similar success in their own endeavors, thus promoting self-improvement as a choice to reduce the comparison gap with relatively fewer personal costs (Meier & Schäfer, 2018; Yu et al., 2018). In contrast, when overall justice perception is low, employees believe that superiors’ achievements are underserved. This induces malicious envy and prompts low-intensity deviant behaviors that aim to pull superiors down, thus causing instigated incivility as a direct and effective means to diminish the envied person and narrow the comparison gap (Crusius & Lange, 2014; Pan et al., 2021; Van de Ven et al., 2009).

Our research offers several contributions to the existing social comparison and justice literature. First, while previous studies have primarily focused on comparisons in specific aspects, our study takes a more comprehensive approach by examining the implications of workplace upward comparisons in an overall fashion (Campbell et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2022b). By doing so, we provide a more holistic view of the impacts of workplace upward comparisons on employees’ behaviors (Gong & Zhang, 2020; Yip & Kelly, 2013). Second, we recognize that overall justice perception serves as a crucial boundary condition in determining workplace upward comparisons, which may lead to either pulling-down or leveling-up effects. Not only does this help reconcile inconsistent findings about the impacts of upward comparisons, but it also broadens the scope of boundary conditions that shape employees’ diverse responses to upward comparisons. Finally, our study deepens the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the pulling-down and leveling-up effects. We propose that benign and malicious envy serve as key mechanisms through which workplace upward comparisons lead to divergent behavioral responses. This insight provides a more nuanced understanding of the complex processes involved in workplace upward comparisons and their consequences in the workplace.

Theory and hypotheses development

Social comparison theory

Social comparison theory suggests that upward comparisons can serve either constructive or destructive functions by evoking assimilation or contrast processes among individuals (Smith, 2000). The assimilation process comes into play when individuals appraise that they can achieve the same level of success as their superiors, leading to assimilative emotions and constructive behaviors aiming at narrowing the comparison gap (Collins, 1996; Mussweiler et al., 2004). Conversely, the contrast process occurs when individuals view their superiors’ achievements as unattainable, resulting in contrastive emotions and destructive behaviors aimed at bringing the superiors down (Collins, 1996; Reh et al., 2018; Xing & Yu, 2006). Furthermore, the nature of assimilation or contrast processes triggered by upward comparisons hinges on individuals’ cognitive appraisal of the deservingness of the referent’s achievement (Smith, 2000).

Envy, a common emotion triggered by upward comparisons, manifests in two forms: benign envy and malicious envy (Crusius & Lange, 2014; Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019). According to social comparison theory (Smith, 2000), different emotions evoked by social comparisons are associated with distinct behavioral responses. The crucial distinction between the two lies in the presence of hostility directed towards the envied person, which ultimately determines whether constructive or destructive behaviors are elicited (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019; Lange et al., 2016). As an assimilative emotion, benign envy motivates individuals to emulate the envied person with the aim of obtaining the same level of success (Carnevale et al., 2023; Van de Ven, 2016; Van de Ven et al., 2009). One common form of leveling-up behavior is self-improvement, which individuals undertake to enhance their performance and success (Lee & Duffy, 2019; Yu et al., 2018). In contrast, malicious envy is a contrastive emotion characterized by feelings of hostility and ill will towards the envied person, leading to behaviors aimed at degrading and undermining them (Brooks et al., 2019; Duffy et al., 2008, 2012). Among the various other-diminishing behaviors that harmful actions directed at the envied targets, one notable form is instigated incivility (Sun et al., 2021; Tai et al., 2023).

One critical aspect influencing these envy responses is the concept of overall justice, which reflects individuals’ general experiences of justice within the workplace (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009; Rubino et al., 2018). It encompasses the sense of justice when one or others receive fair advantages or disadvantages and the sense of injustice when there are unfair advantages or disadvantages (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009). Essentially, employees’ overall justice perception signifies their judgments about the deservingness of others’ achievements (Lange & Crusius, 2015b; Van de Ven et al., 2009; Ven et al., 2012). When individuals perceive others’ achievements as justified and deserved, it fosters benign envy (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019), while perceiving their superiors’ advantages as undeserved triggers malicious envy (Crusius & Lange, 2017; Thiel et al., 2021; Van de Ven et al., 2012). As a result, employees’ overall justice perception plays a pivotal role in determining whether upward comparisons evoke benign envy or malicious envy and subsequently influence the ensuing behavioral responses.

We need to note that two approaches for conceptualizing overall justice have been identified in the literature (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009; Colquitt & Shaw, 2005; Le & Pan, 2021). One approach is adopted by Ambrose and Schminke’s (2009), which reflects individuals’ general experiences of justice within the workplace. Another approach suggested that overall justice could be conceptualized as a higher-order factor that includes distributive justice, procedural justice, informational justice, and interpersonal justice (e.g., Colquitt & Shaw, 2005). We opt for Ambrose and Schminke’s (2009) approach for the following two reasons.

First, in their seminal work, Ambrose and Schminke (2009) argue that a focus on distinct forms of justice “may not provide either a complete or an accurate picture of how individuals make and use justice judgments” (p. 492). They assert that “unless a clear theoretical basis exists for making differential predictions across different subtypes of justice, researchers should assess overall justice instead” (p. 498). Hence, overall justice represents a more parsimonious and precise approach to studying justice compared to focusing on specific dimensions of justice (e.g., Ambrose et al., 2021; Holtz & Harold, 2009; Koopman et al., 2015). Further, the principle of specificity-matching posits that including constructs of similar generality within a single model enhances predictive accuracy (Fisher & Locke, 1992; Hulin, 1991; Roznowski & Hulin, 1992). Consequently, in the context of our study, which investigates the moderating role of overall justice perception on the impacts of employees’ general upward comparisons in the workplace, a focus on overall justice perception is more apt than an examination of specific dimensions of justice (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009; Colquitt & Shaw, 2005). This approach aligns with our interest in understanding the broader implications of overall justice perception, rather than the nuanced effects of its various components.

Workplace upward comparisons

Workplace upward comparisons refer to the process wherein employees compare themselves with their superior colleagues (Festinger, 1954). The past decades have witnessed a proliferation of social comparison literature to understand their consequences in the workplace. We reviewed and synthesized prior studies of the consequences of workplace social comparisons over the last two decades (refer to Online Appendix A https://osf.io/2rdhp/?view_only=01243b28f0aa448d8dc7e0726325ec3a). Through our systematic review of the literature, we have delineated several research gaps pertaining to the consequences of workplace social comparisons.

Until now, an extensive body of literature has delved into the singular and specific aspects of workplace upward comparisons such as employees’ pay, performance, and leader-member exchange (e.g., Bamberger & Belogolovsky, 2017; Campbell et al., 2017; Downes et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022), along with relevant underlying mechanisms. For example, Pan et al. (2021) extensively investigated how the leader-member exchange can serve as upward comparisons information, while Campbell et al. (2017) meticulously examined the impact of upward comparisons triggered by job performance. However, an emerging stream of research emphasizes the importance of holistic workplace upward comparisons (e.g., Chen et al., 2024; Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019). These studies recognize that interactions among colleagues are multifaceted, and employees’ upward comparisons tend to encompass comprehensive aspects rather than just one specific aspect. Furthermore, previous research has concentrated on specific aspects of upward comparisons, which may not be applicable to broader dimensions of social comparison (Gong & Zhang, 2020). Therefore, it is imperative to explore the ramifications of workplace upward comparisons through a more holistic lens.

In addition, existing research has identified that workplace upward comparisons can elicit conflicting individual coping responses, yet majority of these studies have examined only a single effect, either negative or positive (Diel et al., 2021; Koopman et al., 2020). For instance, Tse et al. (2018) advocated that a coworker’s higher leader-member exchange (LMX) can lead to the individual’s feeling of hostility and harmful behaviors toward the coworker; Sun et al. (2021) suggested that a focal employee’s relatively high LMX and task performance may increase the likelihood of coworker undermining via envy. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that upward comparisons can also evoke positive emotions and behavioral responses. For instance, Pan et al. (2021) reported that lower LMX social comparison is associated with self-improvement behaviors through benign envy. Watkins (2021) examined that upward comparisons may improve employees’ inspiration, leading to interpersonal citizenship behavior. Given the existence of these inconsistent findings, it is crucial for us to adopt a contingency perspective, moving away from a simplistic “workplace upward comparisons are either good or bad” paradigm. Instead, we should focus on a more nuanced exploration of the conditions under which such comparisons lead to constructive or destructive responses. Accordingly, our thorough exploration into the contingent consequences of overall upward comparisons is warranted.

Drawing upon social comparison theory, individuals’ cognitive evaluations of their coworkers’ achievements have a critical influence on their positive or negative reactions (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019; Smith, 2000). And further research suggests that individuals may draw on cognitive judgements about the overall fairness of the organization while forming a comprehensive evaluation of an entity (Ambrose & Schminke, 2009; Colquitt & Shaw, 2005). As our study is primarily interested the effects of general upward workplace comparisons on employees, which involves a global assessment of their overall experience in the workplace, this study thus will focus on the critical role of overall justice perception and investigate its boundary impacts on the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and employees’ subsequent emotions and behavioral responses.

The moderating effect of overall justice perception on the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and benign envy

We predict that employees who perceive a higher level of overall justice are more likely to view the advantages of their superior coworkers as deserved, thus triggering benign envy. Specifically, if employees believe that their superior coworkers achieve their relative advantages based on justice and deserved rules, they are less likely to harbor hostile feelings towards these superior referents (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019; Koopman et al., 2020). Instead, they are inclined to believe that the current situation can be changed and that they can also achieve similar success through hard work and effort. This perception of a changeable situation is expected to evoke benign envy, which is an assimilative emotion that acts as a motivator or inspiration to attain better outcomes (Matta & Van Dyne, 2020). Moreover, research from a social comparison perspective suggests that upward referents can serve as models or roadmaps for employees to evaluate their attainable achievements, thereby triggering assimilative emotional responses such as benign envy (e.g., Watkins, 2021). Therefore, based on the above considerations and the theoretical framework established earlier, we propose that when employees perceive a higher level of overall justice, workplace upward comparisons are more likely to elicit benign envy (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019; Van de Ven et al., 2009; Ven et al., 2012). Therefore, we propose that:

-

Hypothesis 1: Overall justice perception moderates the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and benign envy such that the positive relationship will be stronger when overall justice perception is high (versus low).

The moderating effect of overall justice perception on the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and malicious envy

We predict that when employees perceive a lower level of overall justice, they are more likely to evaluate their superior coworkers’ advantages as undeserved, which triggers malicious envy. Specifically, if the achievements of superior others are perceived as a violation of justice rules and undeserved, employees often experience moral outrage (Bies, 1987). This moral outrage results in feelings of hostility towards coworkers who unfairly enjoy superior success, achievement, status, or possessions (Feather & Sherman, 2002). For instance, Singer et al. (2006) found that employees are less likely to empathize with, and may even take pleasure in, the misfortune and pain of their coworkers who attain positive outcomes unfairly. Based on these findings, we propose that employees harbor hostility towards their superior coworkers in response to workplace upward comparisons when they perceive their coworkers as obtaining positive outcomes unfairly. Since hostility is the primary distinguishing factor between benign and malicious envy (Xiang et al., 2018), we predict that workplace upward comparisons are more likely to elicit malicious envy when overall justice perception is low. In this scenario, we propose that when employees perceive a lower level of overall justice, workplace upward comparisons are more likely to elicit malicious envy. Thus, we proposed that:

-

Hypothesis 2: Overall justice perception moderates the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and malicious envy such that the positive relationship is stronger when overall justice perception is low (versus high).

The conditional indirect effect from workplace upward comparisons to self-improvement via benign envy

We hypothesize that when employees perceive overall justice as high, they are more likely to experience self-improvement through benign envy when engaging in workplace upward comparisons. Self-improvement entails an employee’s active efforts to enhance job performance by seeking feedbacks, advices, and opinions from coworkers regarding work-related tasks such as workflows, priorities, and methods (Yu et al., 2018). Benign envy is an assimilative emotion characterized by admiration, motivation to improve, a desire for the envied object, and positive thoughts about the envied person (Falcon, 2015; Van de Ven et al., 2009). We detail the relationship between benign envy and self-improvement as follows:

First, benign envy involves appreciation toward superior others, which serves as a motivational driver for employees to adopt self-improvement strategies with the aspiration to become comparable to or even surpass their superior coworkers (Critcher & Lee, 2018; Watkins, 2021). Second, from the perspective of self-regulation, workplace upward comparisons can foster improvement motivation, leading to efforts to reduce the discrepancy between oneself and the superior coworker (Diel et al., 2021). Self-regulation processes involve the assessment of the existing discrepancy, taking necessary actions, and implementing strategies to reduce the gap (Carver & Scheier, 1982). When employees experience benign envy triggered by workplace upward comparisons, they become aware of the discrepancy between their current status and that of their superior coworkers, compelling them to adopt self-improvement strategies to narrow the comparison gap (Diel et al., 2021). Third, the concept of envy involves three entities: the enviers, the envied persons, and the envied object (Smith & Kim, 2007). Prior research indicates that individuals experiencing benign envy primarily focus on the envied object (Crusius & Lange, 2014). As attainable goals and benchmarks, the envied object provides valuable information for employees to understand how they can reach the same level as their superior coworkers (Crusius & Mussweiler, 2012; Van de Ven et al., 2011a; Ven et al., 2011b). Therefore, benign envy is likely to promote employees’ motivation (Connelly & Torrence, 2018), willingness, and persistence to improve themselves (Andiappan & Dufour, 2020). Fourth, benign envy entails positive thoughts and perceptions about the envied persons, making employees more inclined to take them as role models (Van de Ven et al., 2009). Consequently, employees are motivated to strive for the same level of achievement as their superior coworkers through self-improvement initiatives, such as seeking advice and guidance from them (Pan et al., 2021). In light of the above considerations, we propose that benign envy, triggered by workplace upward comparisons, serves as a potent inducer of self-improvement behaviors among employees.

In sum, when employees engage in workplace upward comparisons and perceive a higher level of overall justice, they are more likely to evaluate their superior coworkers’ positive outcomes as fair and deserving, leading to the experience of benign envy. This benign envy acts as a powerful motivational force, inspiring employees to undertake self-improvement efforts to bridge the comparison gap with their envied colleagues. Thus, we posit that:

-

Hypothesis 3: The indirect effect of workplace upward comparisons on self-improvement via benign envy is stronger when overall justice perception is high (versus low).

The conditional indirect effect from workplace upward comparisons to instigated incivility via malicious envy

We propose that when employees perceive overall justice as low, they are more likely to respond to workplace upward comparisons with malicious envy, which in turn can lead to instigated incivility aimed at pulling their superior colleagues down. Instigated incivility refers to a low-intensity form of deviant behavior that violates norms of mutual respect in the workplace, such as mistreatment, isolation, and verbal aggression (Andersson & Pearson, 1999; Smith & Griffiths, 2022; Tang et al., 2022a). Malicious envy, an emotion characterized by hostility and negative thoughts toward the envied person (Crusius & Lange, 2014), is the driving force behind such harmful behavior. We argue that malicious envy can facilitate instigated incivility through three mechanisms.

First, the hostility component of malicious envy can prompt employees to rationalize their harmful actions (Duffy et al., 2021; Smith & Kim, 2007). In this case, employees experiencing malicious envy tend to believe that instigating incivility to pull their superior coworkers down is justified, thereby increasing the possibility of conducting such behaviors to bridge the gap between them and their superiors (Moore et al., 2012; Thiel et al., 2021). Second, malicious envy redirects employees’ attention from the envied objects to the envied person (Crusius & Lange, 2014). This heightened focus can drive employees to harm their envied coworkers, even at the cost of their success (Pan et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). Third, malicious envy involves negative thoughts (Lee, 2021) toward the envied person (Crusius & Lange, 2014; Van de Ven et al., 2009). According to Van de Ven (2017), these thoughts can propel employees toward engaging in interpersonal deviant behaviors, such as instigating incivility, with the intent of harming their superiors.

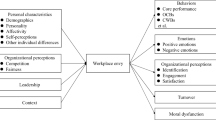

In summary, we posit that when employees perceive overall justice as low, they are more likely to experience malicious envy in response to workplace upward comparisons, and that this emotion can in turn facilitate instigated incivility aimed at reducing the perceived discrepancy between themselves and their envied colleagues. Our theoretical model is depicted in Fig. 1.

-

Hypothesis 4: The indirect effect of workplace upward comparisons on instigated incivility via malicious envy is stronger when overall justice perception is low (versus high).

Method

Sample and procedure

We conducted a three-wave and multisource field survey of full-time employees and their leaders from eight service companies in China. With the personal contacts of one of the authors, we generated a list of service companies where employees work collaboratively and interact with each other to a high degree. These contexts provide sufficient information for social comparisons among employees, thus representing suitable settings to examine our research model (Pan et al., 2021). The common job descriptions included marketing, human resources, and administration.

We used a stratified random sampling strategy to select respondents for the survey, a method widely used in previous studies to ensure the representativeness and generalizability of the sample (e.g., Demirtas et al., 2017; Morgeson et al., 2005; Ozyilmaz et al., 2018). Specifically, we initially categorized the employees of eight service companies based on their department types, such as marketing and human resources, among others. We then conducted a simple random sampling strategy within each department to select participants, ensuring that employees in each department had an equal opportunity to be chosen for the sample (Ozyilmaz et al., 2018). This method was adopted because it was not feasible to reach every employee in the company; hence, we aimed to guarantee representation from all departments in our sample. The HR department assisted us in the sampling process by supplying the required information.

Finally, a total of 87 work teams, comprising 87 leaders and 450 employees, agreed to take part in the study. We emphasized that responses would be voluntary and confidential, and provided the researchers’ contact information for concerns and questions. We distributed paper-and-pencil surveys to the participants during their lunch break and collected their completed surveys on-site. Identification codes were used to match participant surveys across waves and within the team.

To mitigate concerns for common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003, 2012), we conducted three waves of data collection, each was separated by three weeks. At Wave 1, 294 employees completed the survey, which included questions about their workplace upward comparisons, overall justice perception, job efficacy, and demographics (65.3% response rate). Three weeks later, at Wave 2, 282 employees rated their benign and malicious envy towards upward comparisons referents (95.9% response rate). Three weeks later, at Wave 3, 282 employees reported their instigated incivility against the referents (100% response rate). Additionally, 65 team leaders rate their employees’ self-improvement behaviors concerning the past three weeks and demographics (74.7% response rate).

We achieved these relatively high response rates as a result of the support from the HR department and the use of work time to complete surveys (Holtom et al., 2022; Li et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2011). Additionally, we offered a cash incentive of RMB 150 (about 23 USD) to those who completed all the surveys. After matching the responses from the three survey waves, a final sample of 282 employees and 65 leaders was retained for the final data analysis.

Among the 282 employees, 56% were male, Mage = 31.6 years (SD = 6.35), Mwork tenure = 3.67 years (SD = 2.34), Mdyadic tenure = 2.89 years (SD = 1.42); 61% held an associate’s degree and 38.3% held a bachelor’s degree. Among the 65 team leaders, 47.5% were male, Mage = 34.56 years (SD = 5.49), Mwork tenure = 6.77 years (SD = 3.38); 77.7% held a bachelor’s degree. As for the work teams, Mteam size = 10.08 (SD = 4.17), and Mteam tenure = 12.40 years (SD = 4.51). No significant differences in demographics between the final and initial samples (p = 0.74 ~ 0.98).

Measures

We followed the translation and back-translation procedure to translate all English scales into ChineseFootnote 1. Unless otherwise noted, all the measures used a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Workplace upward comparisons (Cronbach’s α = 0.92)

An eight-item scale from Brown et al. (2007) was used to assess workplace upward comparisons (1 = never, 5 = always). Employees rated the frequency with which they compared themselves to superior coworkers along eight dimensions: performance, working conditions, quality of supervision, quality of coworkers, career progression, benefits, prestige, and salary.

Overall justice perception (Cronbach’s α = 0.79)

Overall justice perception was measured using three items from Ambrose and Schminke (2009). This scale has been widely used in research focusing on an individual’s overall assessment of their personal experience with an entity, such as an organization, group, or supervisor (e.g., Koopman et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015). In this study, we invited employees to assess their overall perceptions of justice within their organizations. Sample item includes “Overall, I’m treated fairly by my organization”.

Benign envy (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) and malicious envy (Cronbach’s α = 0.92)

Dual envy was rated using a ten-item scale from Lange and Crusius (2015a), with five items for each type of envy (1 = never, 5 = always). Sample item includes “If I notice that my coworker is better than me, I try to improve myself” (benign envy) and “I feel ill will toward coworker I envy” (malicious envy).

Self-improvement (Cronbach’s α = 0.87)

Leaders used an eight-item scale from Yu et al. (2018) to rate the extent to which employees would solicit assistance or advice from their coworkers who perform better in the past three weeks. Sample item includes “This employee seeks advice/help about specific work tasks from the coworkers who perform better than him/her.”

Instigated incivility (Cronbach’s α = 0.93)

Instigated incivility was rated using a four-item scale from Lim and Cortina (2005). Employees reported the extent to which they engage in incivility towards coworkers who perform better (1 = never, 5 = always). Sample item includes “I pay little attention to their statements or show little interest in their opinion.”

Control variables

Prior studies have found that demographics are important predictors of social comparison emotions (benign and malicious envy) and corresponding behaviors (individual self-improvement and instigated incivility behaviors) (Gabriel et al., 2018; Pan et al., 2021; Zoogah, 2010). We thus controlled for employees’ age, gender, education level, and work tenure to rule out alternative explanations for our findings. For example, we controlled for employees’ age because older employees have less confidence in their abilities to learn new skills, which may diminish their inclination towards self-improvement behaviors (Van Vianen et al., 2011). Gender was also controlled for, given that, in comparison to males, females often report lower self-esteem and a higher propensity for experiencing malicious envy in situations of upward comparisons (Bleidorn et al., 2016; Vrabel et al., 2018). According to social comparison theory, job efficacy, as a significant factor that affects individual responses toward workplace upward comparisons (Van de Ven et al., 2012), was also controlled in our study. Job efficacy (Cronbach’s α = 0.77) was rated using a three-item scale from Wilk and Moynihan (2005). Sample item includes “I am certain that I can meet the performance standards of this job.”

Analysis strategies

Given the multilevel nature of the data (i.e. 282 employees nested in 65 leaders), multilevel modeling was used to test all study hypotheses, which takes into account the non-independence of observations with nested data structure (Bliese & Hanges, 2004). As recommended by Edwards and Cable (2009) and Edwards and Parry (1993), we conducted two-level analyses using “Cluster” and “Type = complex” syntax in Mplus 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). This approach calculated standard errors using the Huber-White Sandwich Estimator to adjust for the non-independence of observations, without strict requirements for between-group variance (Muthén & Muthén, 2017; Schaubroeck et al., 2017). This approach has been widely used in previous research (e.g., Moliterno et al., 2014; Wellman et al., 2019). In addition, we grand-mean centered the exogenous variables to reduce the multicollinearity (Hofmann & Gavin, 1998).

We employed Bauer et al.’s (2006) product of coefficients method to compute the indirect effects at high (M + 1 SD) and low (M − 1 SD) levels of the moderator, as well as their differences. We then used Preacher et al. (2010)’s Bootstrapping approach to obtain a 95% Monte Carlo Confidence Interval (95% MC CIs) to test the significance of the conditional indirect effects with 20,000 bootstrapping samples in RStudio software (Version 2022.07.1). This Monte Carlo method calculates the 95% MC CI for the indirect effects by leveraging the model’s estimates along with their asymptotic variance-covariance matrices, rather than relying on the assumption of a normal distribution (Bauer et al., 2006; Preacher & Selig, 2012). As indirect effects often do not conform to a normal distribution (Liang et al., 2016), this technique offers a robust means of assessing the significance of indirect effects within complex multilevel models such as ours (Preacher & Selig, 2012).

Results

Descriptive statistics of all studied variables and the correlation matrix are reported in Table 1. As expected, benign envy and self-improvement were positively correlated (r = 0.26, p < 0.01); malicious envy was positively connected to instigated incivility as well (r = 0.48, p < 0.01). Furthermore, a significant positive correlation was observed between workplace upward comparisons and malicious envy (r = 0.28, p < 0.01). Although no significant direct relationship was found between workplace upward comparisons and benign envy (r = 0.08, n.s.), the primary focus of our study is to examine the moderating effect of overall justice perception on the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and both benign envy and malicious envy.

Confirmatory factor analyses

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) in Mplus 8.4 to test discriminant validity and convergent validity among variables. According to extant studies (e.g., Farh et al., 2017), the “Type = complex” command was utilized to account for the dependent nature of our data. To optimize the variable-to-sample-size ratio together with minimizing parameter estimate instability, we applied a balanced parceling procedure (Landis et al., 2000). According to the results of factor analysis, we created three indicators for each construct by combining the items that had the highest and lowest loadings within each construct, proceeding to integrate those with the next highest and lowest loadings until all the items were categorized into one of the three indicators. Subsequently, we computed the mean scores of each indicator.

The CFA results indicated that our hypothesized six-factor model demonstrated a better fit to the data (χ2(120) = 179.46, p < 0.01; CFI [the comparative fit index] = 0.96, TLI [the Tucker-Lewis index] = 0.95, RMSEA [the root-mean-square error of approximation] = 0.06, SRMR [the standardized root mean squared residual] = 0.07) than all alternative nested five-factor models (68.86 ≤ ∆χ2 [∆df = 5] ≤ 311.4) and single-factor model (∆χ2[∆df = 15] ≤ 1354.83). Moreover, all factor loadings corresponding to the latent factors were statistically significant (p < 0.01), indicating strong convergent validity among the studied variables.

Hypotheses testing

As depicted in Table 2, the interaction between workplace upward comparisons and overall justice perception significantly and positively predicts benign envy (b = 0.19, SE = 0.08, p = 0.02)Footnote 2. This indicates that the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and benign envy became stronger as overall justice perception increase. The R2 value indicates that 14% variance in benign envy can be explained by our model predictors, which denotes a medium effect size. To show the moderating effect directly, we followed Aiken and West’s (1991) approach to plot the interaction figure at high (+ 1 SD) and low (− 1 SD) levels of overall justice perception. Figure 2 and simple slope tests reveal that the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and benign envy is significant at high levels of overall justice perception (simple slope = 0.16, t = 2.92, p = 0.004), but not significant at low levels of overall justice perception (simple slope = -0.09, t = -1.08, p = 0.282). Therefore, H1 is supported.

As shown in Table 2, the interaction between workplace upward comparisons and overall justice perception significantly and negatively predicts malicious envy (b = − 0.38, SE = 0.14, p = 0.006). This shows that the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and malicious envy tends to intensify for low levels of overall justice perception. The R2 value indicates that 17% variance in malicious envy can be explained by our model predictors, which denotes a medium effect size. Figure 3 shows that the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and malicious envy is significant at low levels of overall justice perception (simple slope = 0.59, t = 4.25, p < 0.001), but not significant at high levels of overall justice perception (simple slope = 0.13, t = 1.26, p = 0.210). Therefore, H2 is supported.

The results presented in Table 2 reveal that benign envy is positively related to self-improvement (b = 0.25, SE = 0.09, p = 0.003). The R2 value indicated that 14% variance in self-improvement can be explained by our model predictors, which denotes a medium effect size. To further validate the moderated mediation effect, we followed the method of Bauer et al. (2006) and estimated the indirect effect of workplace upward comparisons on self-improvement, mediated by benign envy, across two levels of overall justice perception: high (+ 1 SD) and low (-1 SD). As evident from in Table 3, the indirect effect of workplace upward comparisons on self-improvement via benign envy is significant when overall justice perception is high (indirect effect = 0.04, 95% MC CI [0.01, 0.09]), but the effect is not significant when overall justice perception is low (indirect effect = -0.02, 95% MC CI [-0.07, 0.02]). The difference in these indirect effects, amounting to 0.06 (95% MC CI [0.01, 0.14]), is significant. These results indicate that workplace upward comparisons exert an indirect influence on self-improvement via benign envy, but only among employees who perceive a high degree of overall justice, thereby supporting H3.

The results presented in Table 2 also show that malicious envy is positively related to instigated incivility (b = 0.37, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001). The R2 value indicated that 38% variance in instigated incivility can be explained by our model predictors, which denotes a large effect size. Moreover, the indirect effect of workplace upward comparisons on instigated incivility via malicious envy was stronger when overall justice perception is low (indirect effect = 0.22, 95% MC CI [0.10, 0.38]), but the effect is not significant when overall justice perception is high (indirect effect = 0.05, 95% MC CI [-0.03, 0.16]). The difference between the two conditional indirect effects (difference = -0.17, 95% MC CI [-0.31, -0.06]) is significant. These results imply that workplace upward comparisons have an indirect effect on instigated incivility through malicious envy, but only for employees who perceive a low degree of overall justice, thereby supporting H4.

We conducted two robustness checks to improve the validity of our results. First, since our samples were drawn from eight organizations, we created seven dummy variables to represent the eight companies to ensure that our model did not exhibit substantial differences between organizations. After including these dummies as controls and rerunning the models, we found that all hypotheses remained significant. Second, we also reran the model without any control variables and found that the results did not substantially change.

Discussion

Considering that employees’ upward comparisons often encompass comprehensive rather than specific aspects, an emerging stream of research highlights the significance of exploring the consequences of overall workplace upward comparisons (e.g., Gong & Zhang, 2020; Pan et al., 2021). Nevertheless, previous research focusing on singular and specific dimensions of social comparisons may not fully capture the phenomenon of overall social comparisons (Gong & Zhang, 2020). Therefore, it’s imperative to adopt a holistic perspective to investigate the impact of general workplace upward comparisons on employees, thus enhancing our understanding of this important phenomenon. Furthermore, while existing research has identified that workplace upward comparisons can elicit divergent individual coping responses, it typically explores a singular effect, either negative or positive (Diel et al., 2021; Koopman et al., 2020). Given these inconsistent findings, it is crucial to adopt a contingency perspective to investigate the boundary conditions, which differentiate the impact of general workplace upward comparisons on employees’ subsequent emotional and behavioral responses, moving beyond the monolithic “either-good-or-bad” research paradigm.

Based on the social comparison theory, the current study elucidates when and how workplace upward comparisons exert a double-edged sword effect on employees. Results from a multi-wave, multi-source survey involving 282 employees and 65 leaders from 65 teams suggest that workplace upward comparisons can have both leveling-up and pulling-down effects. Specifically, when employees perceive overall justice as high, workplace upward comparisons are more likely to generate benign envy, motivating employees to engage in self-improvement behaviors. However, when employees’ overall justice perception is low, workplace upward comparisons can generate malicious envy, leading to instigated incivility aimed at undermining their superior coworkers.

These findings carry several theoretical and practical implications. The current study is theoretically significant as it elucidates the contingent consequences of workplace upward comparisons on employees’ subsequent responses and identifies overall justice perception as a critical boundary condition. Simultaneously, our research also provides practical implications for organizations and managers, prompting them to acknowledge the potential adverse outcomes of workplace upward comparisons and to proactively enhance employees’ perceptions of overall justice, thereby reaping the benefits of such comparisons. Furthermore, several limitations of our study indicate promising avenues for further research.

Theoretical contributions

Our research has several theoretical implications. First, our research contributes to the workplace upward comparisons literature by focusing on the effects of overall workplace upward comparisons. Workplace upward comparisons are a prevalent and significant phenomenon, yet prior studies have primarily examined singular and specific dimensions of upward comparisons (Bamberger & Belogolovsky, 2017; Campbell et al., 2017; Downes et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2022b). For example, Peng et al. (2024) meticulously crafted a framework to examine the impact of upward performance social comparisons, while Zhang et al. (2023) extensively investigated how the perceived overqualification of employees and peers serves as comparison information that induces ostracism behaviors. However, workplace upward comparisons can encompass various aspects of the work environment, such as salary, performance, and other factors (Brown et al., 2007). Employees are inclined to possess sufficient information for general comparisons due to the frequent and common interactions among colleagues (Pan et al., 2021). Thus, our research makes a fundamental contribution by adopting a more comprehensive perspective to explore the impact of overall upward comparisons, which enhances our understanding of this phenomenon and provides a more holistic view of its effects.

Second, our research sheds light on the dual-edged effects of workplace upward comparisons. While previous studies have largely focused on the detrimental consequences of upward comparisons, some scholars have highlighted its potential positive effects (Li et al., 2022; Obloj & Zenger, 2017; Sun et al., 2021). Drawing upon social comparison theory, our research reveals that workplace upward comparisons can lead to both leveling-up and pulling-down effects. This nuanced approach not only reconciles inconsistent findings in the literature but also offers a more balanced understanding of the consequences of upward comparisons. Moreover, prior research has often treated envy as a singular emotion, with limited exploration of the dual envy framework in organizational contexts (Pan et al., 2021; Smith & Kim, 2007). By investigating the mediating role of both benign and malicious envy, our study not only vividly illustrates how and why workplace upward comparisons generate leveling-up and pulling-down effects but also contributes to the literature on envy.

Lastly, we identify the critical role of overall justice perception in moderating the effects of workplace upward comparisons. In spite of prior research highlighting the contextual dependency of upward comparisons, such as individual beliefs (Bamberger et al., 2017), team identification, and team supportive behaviors (Hu & Liden, 2013), few studies have explored how overall justice perception influences the dynamics of overall upward comparisons in the workplace. Overall justice perception is a pivotal factor that reflects employees’ cognitive evaluation of the deservingness of their coworker’s achievements and influences their behavioral responses (Marescaux et al., 2021). Our findings suggest that overall justice perception serves as a crucial boundary condition that shapes the leveling-up and pulling-down effects of workplace upward comparisons. Specifically, when employees perceive overall justice as high, engaging in workplace upward comparisons is more likely to evoke assimilative emotions (i.e., benign envy) and constructive behaviors (i.e., self-improvement). In contrast, when employees’ overall justice perception is low, workplace upward comparisons are more likely to elicit contrastive emotions (i.e., malicious envy) and destructive behaviors (i.e., instigated incivility). By providing valuable insights on overall justice perception as a crucial boundary condition, our study contributes to the existing literature on justice theory and the contextual variables of upward comparisons.

Practical implications

This research has several practical implications. First, whereas managers often view upward comparisons as a positive means to motivate employees to learn from their superiors in today’s highly competitive workplace (Brown et al., 2007), our study reveals that workplace upward comparisons can have mixed effects on employee outcomes. This highlights a cautionary note for organizations and managers about the potential negative consequences of such comparisons. Specifically, organizations and managers should exercise caution and adopt measures to alleviate the adverse effects of workplace upward comparisons. For example, Liao et al. (2023) underscore the urgency for managers to express appreciation and pay attention to the contribution of inferior employees. Thus, managers can offer both social and instrumental support to those employees to help them navigate and respond to the comparison gap in a positive manner. It is also advisable to equip employees with a thorough understanding of upward comparisons through internal training programs (Li et al., 2023).

Additionally, our findings highlight the pivotal role of overall justice perception as a contextual moderator in influencing the outcomes of workplace upward comparisons. This insight offers valuable guidance for organizations and managers on devising effective interventions to maximize the benefits and minimize the downsides of upward comparisons. It is crucial for organizations and managers to proactively enhance employees’ perceptions of overall justice (Chen et al., 2023). For instance, Aryee et al. (2015) emphasized the significant role of transparency in information, procedures, and policies in shaping employee perceptions of fairness. Consequently, managers should diligently develop transparent reward criteria and efficient information sharing mechanisms (Carlson et al., 2023), thereby ensuring justice in decision-making and performance evaluation processes (Peng et al., 2023).

Furthermore, our findings indicate that envy serves as a mediator, transmitting the effects of upward comparisons to ultimate behaviors. Therefore, organizations can offer employees emotion management training to guide them in constructively managing their emotions. Existing research has shown that this type of training can harness the positive effects of positive emotions while effectively mitigating negative ones (Marescaux et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). Consequently, such training can equip employees to direct their envy towards positive self-improvement behaviors and reduce instances of incivility.

Limitations and directions for future research

While this research has made significant contributions to our understanding of the effects of upward comparisons in the workplace, it is not without limitations. Firstly, although we employed a three-wave, multi-source survey to minimize common method bias and enhance causal inference, our research cannot entirely rule out the possibility of reverse causality. To address this potential issue, we recommend that future research employ experimental designs to test our theoretical model and further establish causality.

Secondly, we acknowledge that the generalizability of our findings to other cultural contexts is limited because we only collected data in China. Nevertheless, we believe the results have the potential to be generalized across different cultural contexts. This stance is supported by previous research, which indicates that workplace upward comparisons and overall justice perception are pan-cultural (Garcia et al., 2013; Jia et al., 2016; Shao et al., 2013). Specifically, upward comparisons, as a fundamental process in human interaction, “may be found in all cultures” (Guimond et al., 2006, p. 319). In line with this, Jia et al. (2016) further posited that “Both Chinese and Western employees are threatened when others outperform them; therefore, social comparison is expected to be independent of culture” (p. 585). Furthermore, overall justice perception has also been shown to transcend cultural boundaries (Shao et al., 2013), playing a vital role in various cultural contexts. Despite this, Chinese culture is known for its high collectivism (Hofstede, 2001), which may decrease the probability of employees exhibiting incivility behaviors in reaction to upward comparisons in the workplace, thereby making our hypothesis tests more conservative. Thus, scholars may benefit from replicating the present investigation across different cultural contexts.

Thirdly, our research focused solely on the role of overall justice perception in moderating the effects of workplace upward comparisons. However, organizational fairness includes different dimensions, such as distributive, procedural, interpersonal, and informational fairness (Colquitt et al., 2001). Thus, we recommend future research to examine the different aspects of organizational justice in moderating the effects of workplace upward comparisons. For example, procedural fairness may impact the effects of workplace upward comparisons by altering employees’ attitudes and behavior toward the organization instead of coworkers (Colquitt et al., 2001).

In addition, social comparison theory suggests that individuals’ cognitive appraisal process determines whether workplace upward comparisons lead to benign or malicious envy. This cognitive appraisal process is influenced by various factors, such as the actors’ characteristics, the targets’ characteristics, and situational factors (Ganegoda & Bordia, 2019). Thus, we encourage future research to expand on our findings by investigating other contextual factors that may moderate the effects of upward comparisons in the workplace, such as performance-prove goal orientation and mastery/performance motivational climate (Diel et al., 2021; Watkins, 2021). For instance, in a mastery motivational climate, employees may perceive their superior coworkers’ advantage as benefiting themselves and may be more likely to experience benign envy in response to workplace upward comparisons. In contrast, in a performance motivational climate, employees may view their superior coworkers as competitors and may be more likely to experience malicious envy in response to workplace upward comparisons (Nerstad et al., 2018).

Finally, our research utilized social comparison theory to examine the emotional mechanisms underlying the relationship between workplace upward comparisons and their outcomes. However, other theories may offer additional insights into how the impacts of workplace upward comparisons unfold. For example, self-regulation theory suggests that individuals focus on the discrepancy between themselves and comparison targets in their pursuit of goals (Diel et al., 2021). Thus, future research could combine self-regulation theory with social comparison theory to explore how and why workplace upward comparisons affect employees’ motivational processes and lead to different behavioral outcomes.

Conclusions

Given the ubiquity of workplace upward comparisons, comprehending their consequences has notable theoretical and practical significance. Drawing upon social comparison theory, we investigated both the leveling-up and pulling-down effects associated with workplace upward comparisons. Our findings revealed that when employees perceive overall justice as high, workplace upward comparisons tend to evoke benign envy, leading to constructive self-improvement behaviors. However, when employees perceive overall justice as low, workplace upward comparisons are more likely to trigger malicious envy, resulting in instigated incivility. Our study has provided a thorough understanding of when and how workplace upward comparisons may lead to disparate behavioral responses by eliciting two distinct forms of envy. We hope that our research will encourage future inquiries into understanding the ramifications of upward comparisons in the workplace.

Data Availability

All data analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

We have included all measurement items in the appendix.

The Mplus syntax and its output for our path analyses can be seen in online Appendix B: https://osf.io/2rdhp/?view_only=01243b28f0aa448d8dc7e0726325ec3a. Data available on request from the authors.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Ambrose, M. L., & Schminke, M. (2009). The role of overall justice judgments in organizational justice research: A test of mediation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 491–500. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013203

Ambrose, M. L., Rice, D. B., & Mayer, D. M. (2021). Justice climate and workgroup outcomes: The role of coworker fair behavior and workgroup structure. Journal of Business Ethics, 172, 79–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04348-9

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202131

Andiappan, M., & Dufour, L. (2020). Jealousy at work: A tripartite model. Academy of Management Review, 45(1), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0299

Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Mondejar, R., & Chu, C. W. (2015). Accounting for the influence of overall justice on job performance: Integrating self–determination and social exchange theories. Journal of Management Studies, 52(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12067

Bamberger, P., & Belogolovsky, E. (2017). The dark side of transparency: How and when pay administration practices affect employee helping. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(4), 658–671. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000184

Bauer, D. J., Preacher, K. J., & Gil, K. M. (2006). Conceptualizing and testing random indirect effects and moderated mediation in multilevel models: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 11(2), 142–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.11.2.142

Bies, R. J. (1987). The predicament of injustice: The management of moral outrage. In L. L. Cummings, & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (Vol. 9, pp. 289–319). JAI.

Bleidorn, W., Arslan, R. C., Denissen, J. J. A., Rentfrow, P. J., Gebauer, J. E., Potter, J., & Gosling, S. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111(3), 396–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000078

Bliese, P. D., & Hanges, P. J. (2004). Being both too liberal and too conservative: The perils of treating grouped data as though they were independent. Organizational Research Methods, 7(4), 400–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428104268542

Brooks, A. W., Huang, K., Abi-Esber, N., Buell, R. W., Huang, L., & Hall, B. (2019). Mitigating malicious envy: Why successful individuals should reveal their failures. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(4), 667–687. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000538

Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Heller, D., & Keeping, L. M. (2007). Antecedents and consequences of the frequency of upward and downward social comparisons at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.10.003

Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. (2007). Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007

Campbell, E. M., Liao, H., Chuang, A., Zhou, J., & Dong, Y. (2017). Hot shots and cool reception? An expanded view of social consequences for high performers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(5), 845–866. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000183

Carlson, D. S., Quade, M. J., Wan, M., Kacmar, K. M., & Yin, K. (2023). Keeping up with the joneses: Social comparison of integrating work and family lives. Human Relations, 76(8), 1285–1313. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267221094686

Carnevale, J. B., Huang, L., Vincent, L. C., Yu, L., & He, W. (2023). Outshined by creative stars: A dual-pathway model of leader reactions to employees’ reputation for creativity. Journal of Management, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063231171071

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1982). Control theory: A useful conceptual framework for personality–social, clinical, and health psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 92(1), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.92.1.111

Chen, K., Wu, Z., & Sharma, P. (2023). Role of downward versus upward social comparison in service recovery: Testing a mediated moderation model with two empirical studies. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75, Article103477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103477

Chen, S., Kou, S., & Lv, L. (2024). Stand out or fit in: Understanding consumer minimalism from a social comparison perspective. Journal of Business Research, 170, Article114307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114307

Chiaburu, D. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2008). Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker effects on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1082–1103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1082

Collins, R. L. (1996). For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51

Colquitt, J. A., & Shaw, J. C. (2005). How should organizational justice be measured. In J. Greenberg, & J. A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of organizational justice (Vol. 1, pp. 113–152). Erlbaum.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, K. Y. (2001). Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.425

Connelly, S., & Torrence, B. S. (2018). The relevance of discrete emotional experiences for human resource management: Connecting positive and negative emotions to HRM. In M. R. Buckley, A. R. Wheeler, & J. R. B. Halbesleben (Eds.), Research in Personnel and Human resources Management (Vol. 36, pp. 1–49). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Critcher, C. R., & Lee, C. J. (2018). Feeling is believing: Inspiration encourages belief in God. Psychological Science, 29(5), 723–737. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617743017

Crusius, J., & Lange, J. (2014). What catches the envious eye? Attentional biases within malicious and benign envy. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.05.007

Crusius, J., & Lange, J. (2017). How do people respond to threatened social status? Moderators of benign versus malicious envy. In R. H. Smithy, U. Merlone, & M. K. Duffy (Eds.), Envy at work and in organizations: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 85–110). Oxford University Press.

Crusius, J., & Mussweiler, T. (2012). When people want what others have: The impulsive side of envious desire. Emotion, 12(1), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023523

Demirtas, O., Hannah, S. T., Gok, K., Arslan, A., & Capar, N. (2017). The moderated influence of ethical leadership, via meaningful work, on followers’ engagement, organizational identification, and envy. Journal of Business Ethics, 145(1), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2907-7

Diel, K., Grelle, S., & Hofmann, W. (2021). A motivational framework of social comparison. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(6), 1415–1430. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000204

Downes, P. E., Crawford, E. R., Seibert, S. E., Stoverink, A. C., & Campbell, E. M. (2021). Referents or role models? The self-efficacy and job performance effects of perceiving higher performing peers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(3), 422–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000519

Duffy, M. K., Shaw, J. D., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2008). Envy in organizational life. In R. H. Smith (Ed.), Envy: Theory and research (pp. 167–189). Oxford University Press.

Duffy, M. K., Scott, K. L., Shaw, J. D., Tepper, B. J., & Aquino, K. (2012). A social context model of envy and social undermining. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 643–666. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0804

Duffy, M. K., Lee, K., & Adair, E. A. (2021). Workplace envy. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8, 19–44. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-055746

Edwards, J. R., & Cable, D. M. (2009). The value of value congruence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 654–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014891

Edwards, J. R., & Parry, M. E. (1993). On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1577–1613. https://doi.org/10.5465/256822

Falcon, R. G. (2015). Is envy categorical or dimensional? An empirical investigation using taxometric analysis. Emotion, 15(6), 694–698. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000102

Farh, C. I. C., Lanaj, K., & Ilies, R. (2017). Resource-based contingencies of when team–member exchange helps member performance in teams. Academy of Management Journal, 60(3), 1117–1137. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0261

Feather, N. T., & Sherman, R. (2002). Envy, resentment, schadenfreude, and sympathy: Reactions to deserved and undeserved achievement and subsequent failure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(7), 953–961. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616720202800708

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Fisher, C. D., & Locke, E. A. (1992). The new look in job satisfaction research and theory. In C. J. Cranny, C. Smith, & E. F. Stone (Eds.), Job satisfaction (pp. 165–194). Lexington.

Gabriel, A. S., Koopman, J., Rosen, C. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2018). Helping others or helping oneself? An episodic examination of the behavioral consequences of helping at work. Personnel Psychology, 71(1), 85–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12229

Ganegoda, D. B., & Bordia, P. (2019). I can be happy for you, but not all the time: A contingency model of envy and positive empathy in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(6), 776–795. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000377

Garcia, S. M., Tor, A., & Schiff, T. M. (2013). The psychology of competition: A social comparison perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(6), 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691613504114

Gong, X., & Zhang, H. (2020). Outstanding others vs. mediocre me: The effect of social comparison on uniqueness-seeking behavior. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(5), 645–658. https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1041.2020.00645

Guimond, S., Chatard, A., Branscombe, N. R., Brunot, S., Buunk, A., Conway, M. A., & Yzerbyt, V. (2006). Social comparisons across cultures II: Change and stability in self-views–Experimental evidence. In Guimond, S. (Ed.), Social comparison and social psychology: Understanding cognition, intergroup relations, and culture (pp. 318–344).

Hofmann, D. A., & Gavin, M. B. (1998). Centering decisions in hierarchical linear models: Implications for research in organizations. Journal of Management, 24(5), 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639802400504

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.).). Sage.

Holtom, B., Baruch, Y., Aguinis, H., & Ballinger, A., G (2022). Survey response rates: Trends and a validity assessment framework. Human Relations, 75(8), 1560–1584. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211070769

Holtz, B. C., & Harold, C. M. (2009). Fair today, fair tomorrow? A longitudinal investigation of overall justice perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(5), 1185–1199. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015900

Hu, J., & Liden, R. C. (2013). Relative leader–member exchange within team contexts: How and when social comparison impacts individual effectiveness. Personnel Psychology, 66(1), 127–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12008

Hulin, C. L. (1991). Adaptation, persistence, and commitment in organizations. In M. D. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 445–505). Consulting Psychologists.

Jia, H., Lu, J., Xie, X., & Huang, T. (2016). When your strength threatens me: Supervisors show less social comparison bias than subordinates. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 89(3), 568–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12142

Koopman, J., Matta, F. K., Scott, B. A., & Conlon, D. E. (2015). Ingratiation and popularity as antecedents of justice: A social exchange and social capital perspective. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 131, 132–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.09.001

Koopman, J., Lin, S. H., Lennard, A. C., Matta, F. K., & Johnson, R. E. (2020). My coworkers are treated more fairly than me! A self-regulatory perspective on justice social comparisons. Academy of Management Journal, 63(3), 857–880. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0586

Landis, R. S., Beal, D. J., & Tesluk, P. E. (2000). A comparison of approaches to forming composite measures in structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 3(2), 186–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810032003

Lange, J., & Crusius, J. (2015a). Dispositional envy revisited: Unraveling the motivational dynamics of benign and malicious envy. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(2), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214564959

Lange, J., & Crusius, J. (2015b). The tango of two deadly sins: The social-functional relation of envy and pride. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000026

Lange, J., Crusius, J., & Hagemeyer, B. (2016). The evil queen’s dilemma: Linking narcissistic admiration and rivalry to benign and malicious envy. European Journal of Personality, 30(2), 168–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2047

Le, H., & Pan, L. (2021). Examining the empirical redundancy of organizational justice constructs. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 165, 21–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2021.03.004

Lee, H. (2021). Changes in workplace practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of emotion, psychological safety and organisation support. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 8(1), 97–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/joepp-06-2020-0104

Lee, K., & Duffy, M. K. (2019). A functional model of workplace envy and job performance: When do employees capitalize on envy by learning from envied targets? Academy of Management Journal, 62(4), 1085–1110. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1202

Li, G., Rubenstein, A. L., Lin, W., Wang, M., & Chen, X. (2018). The curvilinear effect of benevolent leadership on team performance: The mediating role of team action processes and the moderating role of team commitment. Personnel Psychology, 71(3), 369–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12264

Li, C. S., Liao, H., & Han, Y. (2022). I despise but also envy you: A dyadic investigation of perceived overqualification, perceived relative qualification, and knowledge hiding. Personnel Psychology, 75(1), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12444

Li, Y. N., Law, K. S., Zhang, M. J., & Yan, M. (2023). The mediating roles of supervisor anger and envy in linking subordinate performance to abusive supervision: A curvilinear examination. Journal of Applied Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0001141

Liang, L. H., Lian, H., Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Hanig, S., & Keeping, L. M. (2016). Why are abusive supervisors abusive? A dual-system self-control model. Academy of Management Journal, 59(4), 1385–1406. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0651

Liao, H., Feng, Q., Zhu, L., & Guan, O. Z. (2023). The award goes to… someone else: A natural quasi-experiment examining the impact of performance awards on nominees’ workplace collaboration. Academy of Management Journal, 66(5), 1303–1333. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2021.0662

Lim, S., & Cortina, L. M. (2005). Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.483

Marescaux, E., De Winne, S., & Rofcanin, Y. (2021). Co-worker reactions to i-deals through the lens of social comparison: The role of fairness and emotions. Human Relations, 74(3), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719884103

Matta, F. K., & Van Dyne, L. (2020). Understanding the disparate behavioral consequences of LMX differentiation: The role of social comparison emotions. Academy of Management Review, 45(1), 154–180. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0264

Meier, A., & Schäfer, S. (2018). The positive side of social comparison on social network sites: How envy can drive inspiration on Instagram. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 21(7), 411–417. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2017.0708

Moliterno, T. P., Beck, N., Beckman, C. M., & Meyer, M. (2014). Knowing your place: Social performance feedback in good times and bad times. Organization Science, 25(6), 1684–1702. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0923

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Klebe Treviño, L., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

Morgeson, F. P., Delaney-Klinger, K., & Hemingway, M. A. (2005). The importance of job autonomy, cognitive ability, and job-related skill for predicting role breadth and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(2), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.399

Mussweiler, T., Rüter, K., & Epstude, K. (2004). The ups and downs of social comparison: Mechanisms of assimilation and contrast. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 832–844. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.832

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guides [8th Edition]. Muthén & Muthén.

Nerstad, C. G. L., Searle, R., Černe, M., Dysvik, A., Škerlavaj, M., & Scherer, R. (2018). Perceived mastery climate, felt trust, and knowledge sharing. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(4), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2241

Obloj, T., & Zenger, T. (2017). Organization design, proximity, and productivity responses to upward social comparison. Organization Science, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1103

Ozyilmaz, A., Erdogan, B., & Karaeminogullari, A. (2018). Trust in organization as a moderator of the relationship between self-efficacy and workplace outcomes: A social cognitive theory-based examination. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 91(1), 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12189

Pan, J., Zheng, X., Xu, H., Li, J. K., & Lam, C. (2021). What if my coworker builds a better LMX? The roles of envy and coworker pride for the relationships of LMX social comparison with learning and undermining. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(9), 1144–1167. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2549

Peng, Y., Cheng, B., Tian, J., Zhang, Z., Zhou, X., & Zhou, K. (2024). How, when, and why high job performance is not always good: A three–way interaction model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2745

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Preacher, K. J., & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.679848

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141

Reh, S., Tröster, C., & Van Quaquebeke, N. (2018). Keeping (future) rivals down: Temporal social comparison predicts coworker social undermining via future status threat and envy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(4), 399–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000281

Roznowski, M., & Hulin, C. (1992). The scientific merit of valid measures of general constructs with special reference to job satisfaction and job withdrawal. In C. J. Cranny, P. C. Smith, & E. F. Stone (Eds.), Job satisfaction (pp. 123–163). Lexington.