Abstract

Religious and conspiracy beliefs are based on the assumption that a potent force exists which is capable of affecting people’s destinies. According to compensatory control theory, the belief in such a potent external agent may serve to alleviate feelings of uncertainty and help restore a sense of control. This is of particular relevance and importance to attitudes and behaviour of religious individuals towards vaccinations during the Covid-19 pandemic, where a belief in such a potent external force controlling events and destinies may have lowered the sense of threat posed by Covid-19 and in turn reduced vaccination uptake. To test this, we conducted a cross-sectional study of highly religious adults in Poland (N = 213) and found that the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses taken was negatively predicted by conspiracy beliefs, perceived closeness to God, and frequency of church attendance, and positively predicted by the perceived COVID-19 threat. Furthermore, mediation analysis revealed that both conspiracy beliefs and perceived closeness to God were related to a decreased perception of the COVID-19 threat, which in turn led to a decreased number of vaccine doses received. Our study offers important insights for public health professionals and identifies further research pathways on conspiracy and religious beliefs in relation to health-related behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In crises and other high-uncertainty situations, people seek to restore their sense of control by resorting to external systems or higher powers perceived to be acting in their best interests (Landau et al., 2015). Research on the Covid-19 pandemic has shown that mechanisms for restoring a sense of being in control during the pandemic involved religiosity (Leonhardt et al., 2023) and belief in conspiracy theories (Šrol et al., 2021). In this study, we investigate how these mechanisms of dealing with high levels of uncertainty and risk might have affected COVID-19 vaccination behaviours by testing the role of threat perception in the relationship between religious beliefs, conspiracy beliefs, and vaccination behavior, in a population of highly religious Polish adults.

Religiosity, conspiracy beliefs and threat perception

Empirically, relationships between religious beliefs and conspiracy theories are inconsistent and not straightforward (e.g., Frenken et al., 2023; Jasinskaja-Lahti & Jetten, 2019). They depend on political orientation, national context, e.g., religiosity of political forces (Frenken et al., 2023) or trust in political institutions (Jasinskaja-Lahti & Jetten, 2019). However, religiosity and conspiracy beliefs share common ground in terms of (1) fundamental cognitions that shape their exploratory narratives about the world (Robertson, 2017) and (2) the functions they may serve (Frenken et al., 2023). The epistemological similarity between religious and conspiracy ideations lies in the proposal of non-falsifiable, concealed, omnipotent, supernatural-like forces—both benevolent and malevolent—that influence observed events (Robertson, 2017). One function these cognitions may serve, among others (see Frenken et al., 2023, for a review), is to make sense of threatening information.

Religious beliefs provide individuals with a cognitive framework, a set of schemas through which they can interpret their life events and make meaning of situations that might otherwise appear hopeless (Leonhardt et al., 2023; Stewart et al., 2019). Accordingly, religious beliefs might have served as a protective factor amid the uncertainty, randomness, and threats posed by the coronavirus pandemic (e.g., Mahamid et al., 2021; Pirutinsky et al., 2020; Ting et al., 2021). For example, Ting et al. (2021) discovered, in a Malaysian sample encompassing Buddhists, Muslims, and Christians, that the strength of religious beliefs was associated with a reduced perceived stress during COVID-19. Moreover, individuals with stronger religious beliefs reported a greater sense of personal control over COVID-19 and increased understanding of the pandemic (Ting et al., 2021). Research has also shown that positive religious coping was associated with reduced perceptions of stress and fewer depressive symptoms (Mahamid & Bdier, 2021) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pirutinsky et al. (2020) revealed in an Orthodox Jewish sample that trust in God, positive religious coping, and intrinsic religiosity were associated with a reduced perception of the negative impact of the coronavirus pandemic on various life domains. These religious factors were also linked to a positive perception of the pandemic’s impact on people’s lives.

Regarding conspiracy theories, researchers often conclude that these theories are unlikely to alleviate threats and restore a sense of security and control (Heiss et al., 2021; Liekefett et al., 2023; Van Mulukom et al., 2022). For example in the context of COVID-19, Heiss et al. (2021) found, based on an Austrian representative sample, that conspiracy beliefs were positively correlated with the perception of multiple economic, security and health threats related to COVID-19. Furthermore, in their longitudinal study of a German sample, Liekefett et al. (2023) observed that an increase in conspiracy beliefs predicted subsequent increases in anxiety, uncertainty aversion, and existential threat. This suggests that conspiracy beliefs may ultimately contribute to a significantly more negative emotional state. These findings align with the Adaptive Conspiracism Hypothesis (Van Prooijen & Van Vugt, 2018), which posits that across human evolution, conspiracy theories have operated to heighten individuals’ awareness of potential sources of danger, primarily by evoking feelings of fear and anger, rather than mitigating these emotions.

Despite the arguments against the threat-alleviating function of conspiracy theories, several studies reported inverse associations between conspiracy theories and perceptions of the COVID-19 threat. For instance, Hughes et al. (2022) found, in a sample drawn from social media users during the period between the first and second national lockdowns in the UK, that a general inclination toward conspiracy beliefs negatively correlated with individuals’ perceived health threats related to COVID-19. Furthermore, the reduced perception of health threats mediated the relationship between belief in conspiracy theories and compliance with preventive behaviours. Notably, while conspiracy beliefs were negatively associated with perceived health risks, they were positively linked to heightened perceptions of economic and civil liberty risks arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, Imhoff and Lamberty (2020) found that both in UK and US samples, endorsing the specific conspiracy belief that COVID-19 is a hoax was associated with reduced perceptions of COVID-19 threat and decreased engagement in containment-related behaviors.

Compensatory control theory

Compensatory Control Theory (CCT, e.g., Kay et al., 2010; Sullivan et al., 2010) states that threats to personal control can be mitigated by external sources that reintroduce a sense of order and structure into the world. Typically, individuals respond to threats to their sense of control by reinforcing their beliefs in widely accepted sources, such as the effectiveness and power of government or God’s ability to intervene (Kay et al., 2010). However, when these systems themselves are perceived to be disordered, individuals may find solace in the belief that a malevolent force (such as a conspiracy involving large pharmacies) is responsible for chaotic, control-threatening circumstances. Sullivan et al. (2010) showed that belief in a mysterious yet powerful enemy paradoxically restores a sense of control and alleviates perceived threats.

The threat-relieving function of perceived enemies may be particularly important in countries where people cannot trust that sources of control, such as the government, political, and social systems will handle the threat (Stojanov et al., 2023). Relatedly, Stojanov at al., (2023) found that the loss of COVID-19 control predicted an increase in COVID-19-related conspiracy beliefs, but only among North Macedonian participants, who, unlike their New Zealand counterparts, perceived their government to be handling the COVID-19 crisis ineffectively. In the Polish context, it would appear plausible that, given the observed low levels of trust in government and social institutions (OECD, 2022), Poland’s environment would be conducive to embracing both conspiracy theories and religious beliefs as mechanisms to regain a sense of control (Oleksy et al., 2021).

Religiosity, conspiracy beliefs, perceptions of threat and vaccination intent

Against this backdrop, the evidence shows that both religious beliefs and conspiracy theories are related to decreased intention to vaccinate. In a study involving a broad sample of US adults, Upenieks et al. (2022) observed a connection between belief in an engaged God and heightened distrust in the COVID-19 vaccine. Likewise, DiGregorio et al. (2022) identified a negative correlation between the belief in a higher power’s capacity to intervene in the world and the likelihood of planning to receive or having received a COVID-19 vaccine, even after accounting for Christian nationalism. In a large Polish sample, Boguszewski et al. (2020) found that a perceived increase in religious involvement was associated with a disregard for government restrictions as well as a decrease in COVID-19 knowledge. Similar effects may be observed for conspiracy beliefs. Van Prooijen and Böhm (2023) found that individuals’ endorsement of COVID-19 conspiracy theories prospectively predicted vaccination hesitancy in the subsequent months of 2021 during COVID-19. Bertin et al. (2020) found that participants’ intentions to be vaccinated against COVID-19 were negatively predicted by both specific COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs and a general conspiracy mentality (i.e., a predisposition to believe in conspiracy theories). Likewise, in Poland, Cisłak et al. (2021) observed a positive relationship between the endorsement of conspiracy theories and anti-vaccination attitudes.

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT, Rogers, 1975) seems highly relevant in understanding factors predicting vaccination against COVID-19. According to PMT, individuals are more likely to adopt protective behaviors when they perceive a high and probable risk and believe that the protective behaviour is effective in reducing this risk. Indeed, meta-analysis (Galanis et al., 2021) found that vaccination against COVID-19 is positively related to the perception of COVID-19 threat (which includes one’s vulnerability and the severity of the disease) as well as the belief in vaccines as a secure method for safeguarding health. From the perspective of PMT, factors that mitigate the perceived threats related to the disease would indirectly lessen the willingness to engage in protective behaviors. For example, the belief in a caring God (McLaughlin et al., 2013) or ambiguously powerful agents that control the spread of the virus (Sullivan et al., 2010) may alleviate threats of being infected by coronavirus and consequently decrease people’s willingness to seek medical help to protect themselves from the danger. Thus, relying on the control restorative potential of both religious beliefs and conspiracy theories (Landau et al., 2015), we anticipate that these cognitions may decrease willingness to vaccinate to the extent that they reduce the perceived threat posed by COVID-19.

Overall, although existing research suggests a link between increased vaccination hesitancy and both religious beliefs (e.g., DiGregorio et al., 2022) and conspiracy beliefs (e.g., Van Prooijen & Böhm, 2023), so far there is no clear evidence on the role of perception of the coronavirus threat as a potential mediator of these effects. In this study, therefore, we test two hypotheses:

-

1.

There is a negative relationship between (a) religiosity, and (b) belief in conspiracy theories, and the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses taken (Hypothesis 1).

-

2.

Perception of a decreased coronavirus threat would mediate the relationship between (a) religiosity and (b) belief in conspiracy theories, and the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses taken (Hypothesis 2).

Method

Transparency and openness

The data were collected by a student researcher as part of her Master’s thesis within a predefined time frame of three months, spanning from March 2022 to May 2022. No data was excluded. Since the study was conducted as part of a master’s thesis, formal ethical approval was not required initially. Thus, the formal approval from the Ethics Committee of SWPS University (WKE/S2024/04/15/146) was received post hoc. Nevertheless, stringent research ethical standards were rigorously upheld throughout data collection. Participants anonymity was ensured and safeguarded; participants provided informed consent, and were assured of their ability to withdraw from the study at any time. All anonymized data, analysis code, and research materials are accessible at https://osf.io/p6x8b/?view_only=e5ee7afd9a8a43389343b076881c5ff5. The data were analyzed using JASP (Version 0.18.3), a user-friendly open-source software package designed for statistical analysis in psychology and related fields. We chose this software for its comprehensive range of statistical methods and because it facilitates reproducible research by providing clear output and interpretation of results. This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Participants

Because our hypotheses specifically concern the behaviour of religious individuals, we collected data from social media channels, with a particular emphasis on religious Facebook groups. Invitation to the study was shared across the profiles of groups dedicated to exploring religiosity, with the aim of involving as many participants as possible over the designated three-month period. This approach was taken to ensure the participation of individuals who identify strongly with religious beliefs. The final sample included 213 Polish adults (175 women, 38 men) aged 17–74 (M = 38.5; SD = 13.1). No cases were deleted. Participants were highly religious (see Table 1). Most of them were Catholics (n = 191); 19 non-believers, 1 Protestant, 1 Orthodox, 1 marked option “different religious affiliation”.

Materials

Religiosity

We included three questions about participants’ religiosity: the extent to which they (a) believed in God; (b) prayed regularly; and (c) attended church regularly. The answers ranged from 1 (definitely no) to 5 (definitely yes). These three items were strongly correlated (α = 0.88).

Closeness to God was measured with a modified version of a single-item pictorial Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale designed to examine people’s sense of being interconnected with others (Aron et al., 1992). Participants were asked to select the picture that best describes their relationship with God. They were presented with seven figures representing different degrees of overlap of two circles with the instruction that increases in the overlap correspond to feelings of greater closeness to God. Higher values represent larger overlap between the self and God, therefore, increased closeness.

Conspiracy beliefs

The generic conspiracist beliefs scale (Brotherton et al., 2013), Polish adaptation (Siwiak et al., 2019); 15 items (α = 0.94), 1 (definitely untrue) to 5 (definitely true).

Coronavirus threat questionnaire

The perceived threat associated with the coronavirus pandemic was measured with three statements (α = 0.86); “Thinking about the coronavirus COVID-19 makes me feel threatened”; “I am afraid of the coronavirus COVID-19”; “I am stressed around other people because I worry I’ll catch the coronavirus COVID-19,” which were utilized in previous studies on the effects of the pandemic (Conway et al., 2020). The answers ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Vaccine doses

Participants were asked: “How many vaccine doses have you received so far?” The range of doses varied from 0 to 3, which represents the number of doses it was possible to receive by the end of May 2022 in Poland.

Procedure

Participants completed an online survey on Qualtrics. All measures were randomly presented in a rotated order. The questionnaires used in this research were presented along with other measures not related to this study. Data was collected online from March to May 2022, by which time everyone in Poland had the opportunity to receive 3 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine. Until the time of the study, vaccines were available for everyone, and people were officially encouraged by the Polish Ministry of Health to vaccinate. However, the priority in receiving new doses was given to vulnerable groups such as older individuals (aged 60+).

Results

Preliminary analyses

All means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations are presented in Table 1. All indices of religiosity (i.e., religious belief, frequency of prayer, church attendance), perceived closeness to God, and belief in conspiracy theories exhibited negative correlations with the number of vaccine doses taken. Moreover, perceived closeness to God and belief in conspiracy theories were negatively related to the coronavirus threat.

Main analyses

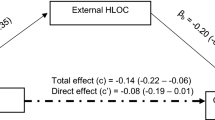

To investigate the mediating effect of perceived coronavirus threat on the uptake of COVID-19 vaccine doses, we conducted a mediation analysis utilizing JASP (Version 0.18.3). We used the bootstrapping procedure with 5000 replications. Figure 1 presents the mediation model. In total, the mediation model accounted for R² = 0.10 for coronavirus threat and R² = 0.29 for vaccination. The results showed that conspiracy beliefs (-0.31, SE = 0.08, z = -4.00, p < .001, 95%CI[-0.47, -0.16]) and closeness to God (-0.10, SE = 0.09, z = -2.50, p = .012, 95%CI[-0.19, -0.00]) predicted a significant drop in perception of coronavirus threat. Interestingly, only perceived closeness to God predicted decreased coronavirus threat among religiosity indices, with no significant correlation found for belief in God, frequency of prayer, or attending church. Additionally, in line with correlation analysis, perceived coronavirus threat predicted increased number of vaccine doses taken, (0.22, SE = 0.06, z = 3.55, p < .001, 95%CI[0.10, 0.33]).

The total effect of belief in conspiracy theories on the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses was significant (-0.51, SE = 0.07, z = -7.08, p < .001, 95%CI[-0.64, -0.37]). As shown in Fig. 1, when controlling for coronavirus threat the direct effect of belief in conspiracy theories on number of COVID-19 vaccine doses was weaker, but still significant (-0.44, SE = 0.07, z = -6.07, p < .001, 95%CI [-0.57, -0.03]). Most importantly, the indirect effect of conspiracy beliefs on decreased vaccination through the coronavirus threat was significant (-0.07, SE = 0.03, z = -2.65, p = .008, 95%CI[-0.13, -0.03]). The total effect of closeness to God on the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses did not reach the level of statistical significance (-0.06, SE = 0.04, z = -1.53, p = .126, 95%CI[-0.13, 0.016]). But, the indirect effect of perceived closeness to God on decreased vaccination through the coronavirus threat was significant (-0.02, SE = 0.01, z = -2.05, p = .041, 95%CI[-0.05, -0.00]). These results suggest that among all religiosity measures included in the study, closeness to God may have potential to reduce perception of coronavirus threat and thus lead to decreased vaccination.

Discussion

The results of our study show that the commonly held viewpoint that COVID-19 conspiracy theories tend to amplify rather than alleviate anxieties and feelings of threat (e.g., Liekefett et al., 2023; Van Mulukom et al., 2022) oversimplifies the relationship between conspiracy beliefs and threat perceptions. Our findings indicate that belief in conspiracy theories correlated with a reduced perception of the threat posed by COVID-19, which statistically contributed to the reduced vaccination rates. This suggests that conspiracy theories may have the potential to reduce perceived threats, contradicting some previous findings (e.g., Heiss et al., 2021; Liekefett et al., 2023), but aligning with others (e.g., Hughes et al., 2022; Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020). Explaining these contradictory results and determining whether (and when) conspiracy theories may alleviate or exacerbate threats is a key priority for future research and theoretical development.

It is worth considering the possibility suggested by Stojanov et al. (2023) that the relationship between threat perception and conspiracy ideation is specific to particular domains. While general anxiety levels tend to correlate positively with conspiracy beliefs (Van Mulukom et al., 2022), in very specific fields, such beliefs may reduce perceptions of threat (Hughes et al., 2022). For example, conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19, such as claims that the virus is a hoax or was engineered by powerful elites to control the world (Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020; Stojanov et al., 2023), may sustain a general sense of danger. However, these beliefs shift the perceived threat from the virus itself to the hidden, malevolent forces allegedly behind it. In this manner, conspiracy theories provide a framework for reinterpretation that shifts focus from the direct threat of COVID-19 to the external forces seen as influencing the global order. While this redirection may reduce the perceived threat of the virus itself, it can contribute to relatively high levels of general anxiety (Molenda et al., 2023). This in turn suggests that CCT (Kay et al., 2010; Landau et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2010) has limitations in explaining how malevolent agents reduce perceived threats. Belief in the controlling power of malevolent agents, such as parties conspiring against humanity, may not be as effective in fulfilling the existential need for safety and security in one’s environment (Douglas et al., 2017) as belief in the controlling power of benevolent agents, such as governments or gods.

We also found that decreased perceptions of the COVID-19 threat were associated not only with conspiracy beliefs but also with a perceived closeness to God. This result aligns with CCT (Kay et al., 2010), demonstrating that the perception of a benevolent and omnipotent figure being close, and thus personally engaged in one’s life, can restore a sense of safety. But it also corroborates attachment theory (Cherniak et al., 2021; Niemyjska & Drat-Ruszczak, 2013), which posits that in times of threat, people seek God as their attachment figure, whose sensed presence alleviates distress (a safe haven function of an attachment figure). Although these two theories can predict similar outcomes, they focus on different mechanisms for managing distress. CCT emphasizes the epistemological process of forming order-producing beliefs, whereas attachment theory highlights proximity seeking as a means of regulating emotions. Given that among all religiosity indices examined in this study—including general belief in God, frequency of church attendance, frequency of prayer, and closeness to God—only the latter predicted lower levels of COVID-19 threat, this suggests that attachment theory provides a more convincing explanation. After all, attachment theory posits that a sense of security is fostered by the feeling of closeness to the attachment figure (Cherniak et al., 2021). The perception of a powerful yet benevolent God being close may lead to a feeling of divine protection, which can cause people to underestimate the risks associated with COVID-19 and the importance of vaccination. This interpretation corroborates Kupor et al.‘s (2015) findings that reminders of God increased risk-taking behavior in nonmoral areas by giving individuals a sense of safety and protection from harm.

Our results offer important insights for public health professionals. We found that conspiracy beliefs and two aspects of religiosity—specifically, perceived closeness to God and frequency of church attendance—were linked to reduced vaccination rates. Furthermore, our data indicated that the reduced vaccination rates could be attributed to diminished perceived threat of COVID-19, influenced by conspiracy beliefs and closeness to God. Overall, these results corroborate Protection Motivation Theory (PMT; Rogers, 1975), which suggests that a reduced perception of threat may discourage individuals from engaging in protective behaviors. If religious and conspiracy beliefs do indeed diminish perceived threat, this has both positive and negative consequences. While a decrease in the perceived immediacy of threats may offer a degree of reassurance, it could also dissuade individuals from taking life-saving preventive measures such as vaccination. However, we do not intend to imply that interventions promoting public health should counteract these effects by emphasizing the threats associated with diseases, as this may only reinforce conspiracy beliefs and reliance on God as established coping methods. Instead, a strategy aimed at promoting health while also restoring a sense of personal control could prioritize evidence-based claims (Orosz et al., 2016) that justify the effectiveness and safety of preventive actions that everyone can take. According to PMT (Rogers, 1975), motivation is driven not only by the perceived severity and likelihood of an adverse event but also by the belief that one’s actions can effectively prevent the event from occurring.

The results of our research contribute to the academic scholarship on the psychological costs and benefits associated with belief in the presence of God and conspiracy theories (Johnson, 2009; Van Prooijen & Van Vugt, 2018). Some researchers argue that these belief systems, shaped by an overprotective cognitive bias, often present lower costs than disbelief (Johnson, 2009; Van Prooijen & Van Vugt, 2018). Yet, our COVID-19-focused study presents a different perspective. When individuals are required to place their trust in unfamiliar sources for protection, such as when considering vaccination, there is a possibility that the perceived costs associated with these beliefs might be underestimated. It is therefore crucial for public health professionals to recognise this potential impact and be prepared to address it accordingly.

Importantly, our study has limitations which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. First, our study uses a cross-sectional design, which means that no causal relationships can be established. Future studies using experimental and longitudinal designs should be conducted to further confirm whether both religious and conspiracy beliefs diminish the perception of disease-related threat, which would result in reduced vaccination intake.

Secondly, the research was conducted during the pandemic’s waning period. As of May 2022, the state of epidemic in Poland was lifted, and a state of epidemic threat came into effect. From 28th March 2022 onwards, most restrictions were lifted. Consequently, it was no longer obligatory to quarantine housemates of COVID-19 patients or to wear face masks, except during visits to medical facilities. As a result of these changes, a mean level of coronavirus threat observed in study was rather low (i.e., M = 2.4; SD = 1.2 on a 7-point scale) as compared to the level observed in other studies at the beginning of pandemic (e.g., M = 4.35; SD = 1.41 on a 7-point scale in Imhoff & Lamberty, 2020). It is noteworthy that, while the high level of religiosity in our sample may have contributed to the relatively low perceived threat of COVID-19, additional factors, such as the conclusion of the pandemic, may have also influenced this level.

Finally, in this study we focused on a single source of threat (cf. Hughes et al., 2022), which limited our ability to observe more nuanced relationships between conspiracy and religious beliefs and various dimensions of threat (e.g., Stojanov et al., 2023). Both conspiracy and religious beliefs, while mitigating certain threats, might exacerbate others. For example, while some conspiracy beliefs relate to a decreased perception of the coronavirus threat (Imhof & Lamberty, 2020) the same beliefs may be linked to an increased perception of the risks associated with COVID-19 vaccination. There may be instances where the overall increase in anxiety outweighs the decrease (e.g., Heiss et al., 2021; Liekefett et al., 2023). However, it is worthwhile to further explore scenarios in which conspiracy and religious beliefs might indeed alleviate threats, as these effects are not obvious from the current state of knowledge (Liekefett et al., 2023).

Data availability

All data, analysis code, and research materials are available at https://osf.io/p6x8b/?view_only=e5ee7afd9a8a43389343b076881c5ff5. This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

References

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,63, 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

Bertin, P., Nera, K., & Delouvée, S. (2020). Conspiracy beliefs, rejection of vaccination, and support for hydroxychloroquine: A conceptual replication-extension in the COVID-19 pandemic context. Frontiers in Psychology, 2471.

Boguszewski, R., Makowska, M., Bożewicz, M., & Podkowińska, M. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on religiosity in Poland. Religions,11(12), 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11120646

Brotherton, R., French, C. C., & Pickering, A. D. (2013). Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: The generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Frontiers in Psychology,4, 279. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279

Cherniak, A. D., Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Granqvist, P. (2021). Attachment theory and religion. Current Opinion in Psychology,40, 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.08.020

Cislak, A., Marchlewska, M., Wojcik, A. D., Śliwiński, K., Molenda, Z., Szczepańska, D., & Cichocka, A. (2021). National narcissism and support for voluntary vaccination policy: The mediating role of vaccination conspiracy beliefs. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations,24(5), 701–719. https://doi.org/10.1177/136843022095945

Conway, I. I. I., Woodard, L. G., S. R., & Zubrod, A. (2020). Social psychological measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus perceived threat, government response, impacts, and experiences questionnaires.

DiGregorio, B. D., Corcoran, K. E., & Scheitle, C. P. (2022). God will protect us: Belief in God/Higher Power’s ability to intervene and COVID-19 vaccine uptake. Review of Religious Research,64(3), 475–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-022-00495-0

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., & Cichocka, A. (2017). The psychology of conspiracy theories. Current Directions in Psychological Science,26(6), 538–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417718261

Frenken, M., Bilewicz, M., & Imhoff, R. (2023). On the relation between religiosity and the endorsement of conspiracy theories: The role of political orientation. Political Psychology,44(1), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12822

Galanis, P., Vraka, I., Siskou, O., Konstantakopoulou, O., Katsiroumpa, A., & Kaitelidou, D. (2021). Predictors of COVID-19 vaccination uptake and reasons for decline of vaccination: A systematic review. MedRxiv, 2021–2007. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.28.21261261

Heiss, R., Gell, S., Röthlingshöfer, E., & Zoller, C. (2021). How threat perceptions relate to learning and conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19: Evidence from a panel study. Personality and Individual Differences,175, 110672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110672

Hughes, J. P., Efstratiou, A., Komer, S. R., Baxter, L. A., Vasiljevic, M., & Leite, A. C. (2022). The impact of risk perceptions and belief in conspiracy theories on COVID-19 pandemic-related behaviours. PloS One,17(2), e0263716. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263716

Imhoff, R., & Lamberty, P. (2020). A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Social Psychological and Personality Science,11(8), 1110–1118. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620934692

Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., & Jetten, J. (2019). Unpacking the relationship between religiosity and conspiracy beliefs in Australia. British Journal of Social Psychology,58(4), 938–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12314

Johnson, D. D. P. (2009). The error of God: Error management theory, religion, and the evolution of cooperation. In S. A. Levin (Ed.), Games, groups, and the global good (pp. 169–180). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-85436-4

Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., McGregor, I., & Nash, K. (2010). Religious belief as compensatory control. Personality and Social Psychology Review,14(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309353750

Kupor, D. M., Laurin, K., & Levav, J. (2015). Anticipating divine protection? Reminders of God can increase nonmoral risk taking. Psychological Science,26(4), 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614563108

Landau, M. J., Kay, A. C., & Whitson, J. A. (2015). Compensatory control and the appeal of a structured world. Psychological Bulletin,141(3), 694–722. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038703

Leonhardt, N. D., Fahmi, S., Stellar, J. E., & Impett, E. A. (2023). Turning toward or away from God: COVID-19 and changes in religious devotion. Plos One,18(3), e0280775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0280775

Liekefett, L., Christ, O., & Becker, J. C. (2023). Can conspiracy beliefs be beneficial? Longitudinal linkages between conspiracy beliefs, anxiety, uncertainty aversion, and existential threat. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,49(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211060965

Mahamid, F. A., & Bdier, D. (2021). The association between positive religious coping, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms during the spread of coronavirus (COVID-19) among a sample of adults in Palestine: Across sectional study. Journal of Religion and Health,60, 34–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01121-5

McLaughlin, B., Yoo, W., D’Angelo, J., Tsang, S., Shaw, B., Shah, D., Baker, T., & Gustafson, D. (2013). It is out of my hands: How deferring control to God can decrease quality of life for breast cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology,22(12), 2747–2754. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3356

Molenda, Z., Green, R., Marchlewska, M., Cichocka, A., & Douglas, K. M. (2023). Emotion dysregulation and belief in conspiracy theories. Personality and Individual Differences,204, 112042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.112042

Niemyjska, A., & Drat-Ruszczak, K. (2013). When there is nobody, angels begin to fly: Supernatural imagery elicited by a loss of social connection. Social Cognition,31(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2013.31.1.57

OECD Data (2022). Retrieved from: https://data.oecd.org/gga/trust-in-government.htm#indicator-chart

Oleksy, T., Wnuk, A., Gambin, M., & Łyś, A. (2021). Dynamic relationships between different types of conspiracy theories about COVID-19 and protective behavior: A four-wave panel study in Poland. Social Science & Medicine,280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114028

Orosz, G., Krekó, P., Paskuj, B., Tóth-Király, I., Bőthe, B., & Roland-Lévy, C. (2016). Changing conspiracy beliefs through rationality and ridiculing. Frontiers in Psychology,7, 216563. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01525

Pirutinsky, S., Cherniak, A. D., & Rosmarin, D. H. (2020). COVID-19, mental health, and religious coping among American orthodox jews. Journal of Religion and Health,59(5), 2288–2301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01070-z

Robertson, D. G. (2017). The hidden hand: Why religious studies need to take conspiracy theories seriously. Religion Compass,11(3–4), e12233. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec3.12233

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. The Journal of Psychology,91(1), 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803

Siwiak, A., Szpitalak, M., & Polczyk, R. (2019). Generic conspiracist beliefs scale–Polish adaptation of the method. Polish Psychological Bulletin,50(3), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.24425/ppb.2019.130699

Šrol, J., Ballová Mikušková, E., & Čavojová, V. (2021). When we are worried, what are we thinking? Anxiety, lack of control, and conspiracy beliefs amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Applied Cognitive Psychology,35(3), 720–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3798

Stewart, W. C., Wetselaar, M. J., Nelson, L. A., & Stewart, J. A. (2019). Review of the effect of religion on anxiety. International Journal of Depression and Anxiety,2(2), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.23937/2643-4059/1710016

Stojanov, A., Halberstadt, J., Bering, J. M., & Kenig, N. (2023). Examining a domain-specific link between perceived control and conspiracy beliefs: A brief report in the context of COVID-19. Current Psychology,42(8), 6347–6356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01977-0

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J., & Rothschild, Z. K. (2010). An existential function of enemyship: Evidence that people attribute influence to personal and political enemies to compensate for threats to control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,98(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017457

Ting, R. S. K., Yong, A., Tan, Y. Y., M. M., & Yap, C. K. (2021). Cultural responses to COVID-19 pandemic: Religions, illness perception, and perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology,12, 634863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.634863

Upenieks, L., Ford-Robertson, J., & Robertson, J. E. (2022). Trust in God and/or science? Sociodemographic differences in the effects of beliefs in an engaged god and mistrust of the COVID-19 vaccine. Journal of Religion and Health,61(1), 657–686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01466-5

Van Mulukom, V., Pummerer, L. J., Alper, S., Bai, H., Čavojová, V., Farias, J., & eželj, I. (2022). Antecedents and consequences of COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine,301, 114912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114912

Van Prooijen, J. W., & Böhm, N. (2023). Do conspiracy theories shape or rationalize vaccination hesitancy over time? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 19485506231181659. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506231181659

Van Prooijen, J. W., & Van Vugt, M. (2018). Conspiracy theories: Evolved functions and psychological mechanisms. Perspectives on Psychological Science,13, 770–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618774270

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

We have no known conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rabinovitch, A., Bliuc, AM., Strani, K. et al. “God is my vaccine”: the role of religion, conspiracy beliefs, and threat perception in relation to COVID-19 vaccination. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06475-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06475-7