Abstract

Mexico is one of the most diverse countries with numerous social minorities such as indigenous Mexicans, but also immigrants coming from countries so different like Honduras or the United States (US). The relationship between stereotypes about minorities and perceived threat has been extensively studied; however, it has not been tested whether such a relationship varies according to the target evaluated. We compared the stereotypes of Mexicans toward indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants, and analyzed their relationship with perceived threat, perceived discrimination, and quantity of contact. Six hundred and thirty-five Mexican participants (62.5% female, Mage = 29.07) answered an online questionnaire reporting their stereotypes of (im)morality, sociability, and competence of the outgroup (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, or Honduran immigrants), and of the ingroup (Mexican majority), perceived threat and discrimination of the three minorities, and their quantity of contact with them. Results showed that indigenous Mexicans were the best-evaluated group in all stereotype dimensions, and were considered the least threatening and the most discriminated group. Perceived (im)morality of US and especially of Honduran immigrants was associated with perceptions of realistic threat, but this association was not sustained when evaluating indigenous Mexicans. Our findings may contribute to understanding the complexity when evaluating different minorities in Mexico and some of the psychosocial processes involved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the psychosocial literature, many studies analyze stereotypes held toward other social groups. However, it is less common to find studies that also consider self-stereotypes (i.e., stereotypes about the ingroup) of evaluators (e.g., Kervyn et al., 2008; Koomen & Dijker, 1997; Yzerbyt et al., 2005), and even less in the Mexican context. In this study, it is proposed that an adequate understanding of the stereotypes toward different social minorities requires considering the stereotypes toward the outgroup not in absolute terms, but rather in a relative way, in comparison with the stereotypes attributed to the ingroup (e.g., Ball, 1983; Oldmeadow & Fiske, 2007). Previous research on social cognition has shown that the perception of a group is influenced by the group with which it is compared (Kervyn et al., 2008). Despite the relevance of this assumption, most studies have focused on the European context and have been limited to the two fundamental stereotype dimensions of warmth and competence. However, the most recent research on social perception has shown that (im)morality, as subdimensions of warmth, play a key role in intergroup perception (Brambilla & Leach, 2014; Rusconi et al., 2020). In general, there is still no evidence that compares the evaluation of the outgroup with the ingroup in the four dimensions of morality, immorality, sociability, and competence. Furthermore, this is especially relevant in a highly diverse context such as Mexico, which offers the opportunity to evaluate different minorities such as indigenous people, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants. The relationship between stereotypes toward minorities and perceived threat has also been studied, but often without addressing the possibility that it depends on the minority being evaluated. Considering the importance of the target group in this relationship, as well as the comparison between outgroup and ingroup stereotypes may be a key to broadening the understanding of these essential psychosocial variables.

Mexico is one of the most diverse countries in the world with different ethnic and national minorities conforming a complex and multicultural society. Some minorities share Mexican nationality such as indigenous Mexicans, while others come from different countries such as the United States (US) or Honduras. These minorities live unique social realities in Mexico, generally with dissimilar economic resources and degrees of social integration, and have different characteristics (e.g., language, religion, nationality, socioeconomic status) that can be related to distinct levels and forms of intergroup interactions. The Mexicans’ perceptions of these groups can vary depending on their stereotypes, perceived threat, quantity of intergroup contact, or perceived discrimination. However, the comparisons of perceptions concerning these minorities in a society such as the Mexican have not been extensively studied, and even less attention has been directed to the relationship of stereotypes of (im)morality, primary in social judgments, with perceived threat and perceived discrimination in this context. In this study, we analyzed and compared the stereotypes of (im)morality, sociability, and competence of a sample of Mexicans toward indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants, and toward their own group, the Mexican majority. We also compared the quantity of contact of Mexicans with the three minorities, and their perceived threat and discrimination to analyze their relationship with the different stereotype dimensions.

Minorities in Mexico

Mexican society has gone through a history of European-indigenous miscegenation that has given rise to different groups. Although many subgroups can be found (there are many different indigenous communities [e.g., Nahua, Maya, Zapotec, Huichols] and other social groups [e.g., afro Mexicans]), one of the most common forms of grouping is based on whether they belong to indigenous communities. According to this, on the one hand, there is the majority society (often called mestizos) that shares elements of miscegenation (i.e., the acquisition of the Spanish language), and on the other hand, there are the indigenous communities that have preserved the pre-colonization culture to a greater extent and have a specific ethnic identity and their own minority culture that is different from the majority culture in Mexico. Generally, the majority identify themselves first as Mexicans, meanwhile, indigenous Mexicans identify first as a member of some indigenous community since that is essential to their identity. It has even been proposed that one element that unifies the variety of groups in the Mexican majority society is the difference they perceive from the indigenous Mexicans (Navarrete, 2004).

Nowadays, Mexico is a multicultural country in which numerous and diverse communities, both native and foreign, reside. Mexican society, in general, has been perceived as having characteristics related to sociability (e.g., friendly; Díaz-Loving & Draguns, 1999), and it has even been proven that they behave more sociable than other groups in their everyday lives (i.e., US people; Ramírez-Esparza et al., 2009).

Indigenous Mexicans are one of the most representative minorities in the country. Specifically, the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI, 2020) reported that 7,364,645 people speak an indigenous language in Mexico (6.1% of the population). The predominance of positive stereotypes of indigenous Mexicans (e.g., intelligent, hardworking, friendly, good) versus negative stereotypes (e.g., unfair, disloyal, treacherous) has been shown in Mexican students (Muñiz et al., 2010). In addition, a qualitative study found that non-indigenous Mexican students manifested positive stereotypes (i.e., hardworking, wise, kind, honest, and trustworthy) toward indigenous people in Mexico (Echeverría, 2016). Despite the above, indigenous people are perceived as the most discriminated group in the country and there is evidence that corroborates this perception (Gutiérrez & Valdés, 2015), with the majority society itself recognizing the rights of indigenous people are not respected and stating that the greatest disadvantage of being indigenous is the discrimination they receive.

It becomes essential to know the quantity of intergroup contact since groups with more levels of contact generally have better intergroup relationships (see Allport, 1954, and meta-analyses by Lemmer & Wagner, 2015, and Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006, 2008). Even though the number of indigenous people in Mexico is significant, there are low levels of contact with them (Muñiz et al., 2010), which is not surprising as they are socially excluded (e.g., Gracia & Horbath, 2019) and live under conditions of high precariousness framed in a generalized of structural marginalization. Hence, being indigenous in Mexico is an obstacle for different aspects, among which stand out having optimal health care (Juárez-Ramírez et al., 2014), access to the educational system (Köster, 2016), equal labor conditions (Vázquez-Parra, 2020), as well as having favorable housing conditions (Gracia & Horbath, 2019).

Another important minority group in Mexico is the group of foreigners. In the last census conducted in the country (INEGI, 2020), it was estimated that 1,216,995 foreign-born persons resided in Mexico. Of this total, most foreigners (i.e., 65.5%) were originally from the United States. Although US migration has been occurring for more than a century (Palma-Mora, 2009), it is estimated to have increased substantially in recent years (Soriano, 2023). Many of US immigrants are pensioners or have sufficient resources (Rodríguez & Cobo, 2012) and the benefit acquired by their pensions is the main factor attracting them to migrate (i.e., cheaper real estate and medical services). Although most of them are not fluent in Spanish, they live with Mexicans in an atmosphere of tolerance and mutual respect, while continuing a US lifestyle (Lizárraga, 2008). There are also young US citizens who live in Mexico having good opportunities, and sometimes even better job positions and conditions than young Mexicans (Meza-González & Orraca-Romano, 2022).

This contrasts with the reality of other migrant groups, such as Hondurans, who have had a growing presence in Mexico in recent years (2.9% of foreigners in Mexico), mainly due to the social phenomenon of migrant caravans in which large groups of people cross Mexico (e.g., Ruíz-Lagier & Varela-Huerta, 2020) fleeing economic, social and political realities (i.e., poverty, crime), using slogans such as “we are not leaving because we want, we are being expelled by violence and poverty” (Nájera-Aguirre, 2019, p. 6). The modality in which Hondurans have migrated in recent years forming caravans has been widely publicized in the mass media, presenting them as arriving in large groups (e.g., Manetto, 2021), seeking refuge and better living conditions. The mass media report that Honduran migrants who cross Guatemala and then try to reach the southern Mexican border come in conditions of extreme poverty, seeking either asylum in Mexico, or crossing into the United States (e.g., Suárez-Jaramillo, 2022).

The causes and forms of migration of US and Honduran immigrants are different. While US immigrants have sufficient resources to reside in Mexico and generally have better institutional conditions to migrate (i.e., currently US citizens do not need a visa to visit Mexico), Hondurans migrate under precarious conditions, as many times, during their journey, they find themselves in need of begging for money or traveling on the top of trains (e.g., “la bestia” [“the beast”]) to continue their journey and seek opportunities at their destination. In addition to the differences between the migratory characteristics of these groups, Mexicans also perceive them differently. Indeed, Mexicans perceive that the rights of foreigners are more respected if they come from the United States and perceive them as the most respected and trustworthy, as well as the least discriminated group. Hondurans, on the other hand, are one of the groups perceived as the most discriminated against and the least trusted (Caicedo & Morales, 2015).

Mexico is a diverse country and therefore it is essential to consider the role of psychosocial variables toward different groups such as indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants. In this way, we can analyze a native ethnic minority, a foreign ethnic minority of high socioeconomic status and consolidated in Mexico, and a foreign ethnic minority relatively new to the country and with special migratory conditions.

The role of stereotypes in social perception

Stereotypes have been defined as “a set of beliefs about the personal attributes of a group of people” (Ashmore & Del Boca, 1981, p. 16). Stereotypes are a product of the social categorization process (Schneider, 2005) and the consideration of an outgroup as a differentiated social entity regarding its own ingroup. Stereotypes are activated by accessing knowledge about a social group (Gilmour, 2015). The evaluation of the own group depends on the comparisons with others (Turner et al., 1979), and self-group stereotypes, especially regarding morality, have been shown to play a central role in individuals’ self-image and self-concept (Leach et al., 2007).

According to the Stereotype Content Model (Fiske et al., 2002), primarily two stereotype dimensions (warmth and competence) help to evaluate social groups. In intergroup relations, warmth represents the perceived outgroup intentions, and competence refers to the ability to achieve its goals. Leach et al. (2007) identified two sub-dimensions within the global dimension of warmth: morality and sociability. Morality refers to the correctness of others through traits such as trustworthiness, while sociability refers to cooperation with others through traits such as being friendly. This three-dimensional model (morality, sociability, and competence) has shown a better fit in different contexts (Brambilla et al., 2011; López-Rodríguez et al., 2013). Morality is the most relevant dimension in both ingroup (Leach et al., 2007) and outgroup evaluation (Brambilla et al., 2013) and plays a central role in the formation of first impressions (Brambilla et al., 2012). Moreover, morality is the dimension that best distinguishes between evaluations of different immigrant groups (López-Rodríguez et al., 2013). Recently, Rusconi et al. (2020) have proposed that negative attributes of morality (vs. positive) might have greater weight in the formation of impressions, and there is evidence that considering negative attributes of morality (i.e., immorality) contributes to explaining outgroup evaluations (Sayans-Jiménez et al., 2017). Hence, both the positive and negative sides of morality should be considered when analyzing intergroup stereotypes.

Fiske et al. (2002) suggest that while ingroup favoritism may lead to evaluating one's own group as warm and competent, evaluating outgroups as high in competence or warmth but low in the other dimension (i.e., mixed stereotypes) allows maintaining the status quo and defending the position of the social reference groups. In this line, Kervyn et al. (2010) noted a compensation effect that occurs when two groups or individuals are judged and compared: the one who is judged more positively on one dimension is also judged less positively on the other dimension. This effect is more likely to occur in comparative intergroup contexts and specifically in the fundamental dimensions of social perception (i.e., warmth and competence). According to these authors, one possible interpretation of the compensation effect is related to the system justification theory (e.g., Jost & Banaji, 1994), in which people would prefer to evaluate groups in a balanced view to justify the social existing structure. In this way, the compensation effect would bias the perceptions of participants when they form first impressions of two groups (Judd et al., 2005) in order to create a system in which both groups would have strengths and weaknesses thus creating an illusion of justice (Kervyn et al., 2010).

The evaluation of the warmth or competence of one's own group depends on whether it is compared to a warmer or more competent group (Kervyn et al., 2008). Therefore, ingroup favoritism may not occur equally in all dimensions. High-status groups usually see themselves and might be seen as more competent than warm, while low-status groups are seen as warmer than competent (Oldmeadow & Fiske, 2010). El-Dash and Busnardo (2001) compared stereotypes of their own group and of different outgroups in Brazil showing that they perceived other groups (i.e., Germany, Bolivia) as having the highest levels of work-related values, even higher than their own, but perceived themselves as having the highest personal warmth and social agreeableness. Consistent with the finding by Leach et al. (2007), those aspects related to warmth, especially morality, seemed to be more important for the evaluation of the ingroup than aspects related to competence.

According to Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel & Turner, 1979), it is precisely the motivation to have a positive self-concept or self-image that leads to a more positive evaluation of the groups to which the individual belongs and, therefore, to favor their ingroup in terms of evaluations and behavior (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Groups tend to compete on attributes they consider important (Turner et al., 1979). However, when the ingroup is not well evaluated compared to other groups, resulting in a negative social identity, people may adopt different strategies (e.g., creatively comparing the ingroup with the outgroup in a dimension where the ingroup wins; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Therefore, research must consider both stereotypes about the outgroup and the ingroup as this comparison has barely been considered in the literature of social perception. Additionally, we should improve our comprehension of how stereotypes about the outgroup can be a powerful source of threat.

The importance of threat

According to Intergroup Threat Theory (Stephan & Renfro, 2002; Stephan et al., 2015), outgroups can generate realistic threat when they compete with the ingroup for scarce and valuable resources (e.g., territory, wealth, employment, education), and/or symbolic threat when they embrace values, beliefs, or attitudes different from those of the ingroup. Recognizing the differences between the two types of threat is essential. Interventions that attempt to reduce one type of threat but rely on the other may be ineffective and even counterproductive (Rios et al., 2018).

Moreover, negative stereotypes about outgroup members (e.g., perceiving them as immoral or dishonest) can generate negative expectations of interaction with the outgroup (e.g., expecting low performance or suspicious actions) and trigger threat (Stephan & Renfro, 2002). Therefore, increasing the salience of these stereotypes is shown to be a way to intensify realistic and symbolic threats (Stephan et al., 2015).

Among stereotypes, morality has been found to be the only dimension that predicts the perception of threat (vs. competence and sociability) generated by members of outgroups (e.g., Brambilla et al., 2012), demonstrating that in conditions of low morality, the perception of threat was higher. This closer relationship between morality and threat can be explained by the fact that knowing the morality of others can protect one's own group from external threats (Alexander, 1985). The main function of the information seeking and impression formation process is to identify the potential threat posed by the other (Wojciszke et al., 1998), so the importance of morality lies in the fact that it informs us of the benefit or harm that others may pose to our own or our group's well-being (Brambilla et al., 2011). Different groups have been associated with different types of threat (e.g., Morrison & Ybarra, 2008). However, studies often focus on a single target without addressing whether the relationship between outgroup stereotypes and perceived threat may vary between different targets. Therefore, it is unclear whether some characteristics associated with the target may be critical in this relationship.

The present study

The study was designed to cover some gaps identified in the literature on social perception and intergroup relations in general, particularly in the Mexican context. First of all, no previous studies have systematically analyzed the stereotypes of Mexicans toward three relevant social groups in the same study (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants), as well as their perceived threat toward such groups, their perceived discrimination, and their level of contact with them. We consider this contextual contribution relevant as most studies with these variables have been conducted with Western samples, and we aimed to understand how they can apply in a multicultural reality such as the Mexican society, capturing the evaluative comparisons toward different groups. Previous studies in the European context have found that morality is an especially diagnostic stereotype dimension that allows making fine distinctions in the evaluations of different immigrant groups (e.g., López-Rodríguez et al., 2013), but we do not know yet whether morality should have the same prominent role in the Mexican society. Similarly, we do not know the differences in perceived threat, perceived discrimination, and level of contact with these groups.

However, the novelty of the study is not limited to a contextual contribution. Methodologically, despite some exceptions, studies on social perception tend to focus on the evaluation of the outgroup in absolute terms, without offering a measure of relative comparison with the perception of the ingroup. Here, we propose that stereotypes may be better understood by comparing the evaluators’ perceptions of the outgroup and the ingroup. This implies comparing how Mexican participants perceive US immigrants and Honduran immigrants compared to Mexicans, and indigenous Mexicans compared to non-indigenous Mexicans.

Finally, we aimed to improve our knowledge about the relationship between stereotypes and threat. Negative stereotypes about the outgroup may work as a base for negative expectations and, consequently, elicit threat among the evaluator (Stephan et al., 2002). Previous research has demonstrated that perceived threat mediates the relationship between moral traits and global evaluation of the outgroup (Brambilla et al., 2012), as well as the relationship between the stereotypes and acculturation preferences of the majority group about immigrants (López-Rodríguez et al., 2014). However, no previous research has tested whether the relationship between stereotypes and perceived threat can vary depending on the outgroup assessed. It is plausible that the relationship between stereotypes and threat may be stronger in the case of less familiar groups (as there is less concrete knowledge about them and they are perceived as more homogeneous) and less valued groups.

Although previous research has explored the stereotypes and threat of Mexicans toward some minorities (e.g., Honduran immigrants, Vázquez-Flores et al., 2022), a systematic comparison to understand how different minorities are perceived is still needed. We analyzed and compared the stereotypes of morality, sociability, competence, and immorality of Mexicans toward the ingroup and indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants.

Table 1 shows the different hypotheses. Considering previous findings in which indigenous Mexicans have been perceived with positive aspects related to morality (i.e., trustworthy), sociability (i.e., friendly), and competence (i.e., intelligent) (Echeverría, 2016; Muñiz et al., 2010) we suppose that the evaluation of indigenous people will be positive in these stereotype dimensions. The Mexican majority may favor the Indigenous by empathizing with them as the group that suffers the most discrimination. In addition, both the Mexican majority and the indigenous people share a superior category (Mexicans), so the recategorization process (Gaertner et al., 1993) could explain a possible ingroup favoritism toward the most discriminated Mexicans (i.e., indigenous). Therefore, we expect that the stereotypes about indigenous people will be better compared to the stereotypes about US and Honduran immigrants (Hypothesis 1).

However, indigenous Mexicans have been socially excluded in several areas (e.g., health care, Juárez-Ramírez et al., 2014; access to the educational system, Köster, 2016); we suppose that the levels of realistic threat elicited by this group will be low. Given that realistic threat occurs by competition with another group for resources that are considered limited and indigenous Mexicans could be considered part of the ingroup in a higher category (i.e., Mexicans), we believe that indigenous Mexicans will elicit less realistic threat than US and Honduran immigrants (Hypothesis 2). On the other hand, we expect that Mexicans may feel more symbolically threatened by US people (Hypothesis 3), with whom they differ more in cultural aspects such as language and religion, which have exacerbated their historically complex relationships (Eller & Abrams, 2003).

Furthermore, we expect that indigenous people will be perceived as the most discriminated group in the study (Hypothesis 4), coinciding with the extensive literature demonstrating the high levels of discrimination of this group in Mexico, even being perceived as the most discriminated group in the country (Gutiérrez & Valdés, 2015). Previous literature (Caicedo & Morales, 2015) indicates that Hondurans will be perceived to suffer greater discrimination than US immigrants, something that would not be surprising considering their migratory and living conditions in Mexico.

In view of the importance of intergroup contact in intergroup relations (see meta-analyses by Lemmer & Wagner, 2015, and Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006, 2008) and its relationship with morality (Brambilla et al., 2013), we also compared the quantity of contact of Mexicans with the three minorities. Population demographics establish that the number of Hondurans is much smaller than that of indigenous Mexicans and US immigrants in Mexico (INEGI, 2020). In addition, Hondurans are “in transit” without becoming fully established in the country. This suggests that the amount of contact with Honduran immigrants will be less than with US immigrants and indigenous people (Hypothesis 5), although in general low levels of contact are expected with all three groups.

In this study, we also analyzed the relationship of the different stereotype dimensions with perceived threat, perceived discrimination, and quantity of intergroup contact. These relationships have been studied extensively; however, it has not been done previously with three minorities in Mexico jointly. In that vein, our first aim was to find out whether stereotypes, in particular morality and immorality, are related to realistic and symbolic threat, perceived discrimination, and contact with the outgroup, and whether this relationship occurred equally across groups. The stereotype dimensions of (im)morality are basic in the process of social perception and have been related to the perception of outgroup threat (Brambilla et al., 2012; Stephan et al., 2015), without considering whether this relationship was equal in the different groups. Therefore, our second objective was to explore whether the relationship between stereotypes and perceived threat varied depending on the ethnic minority assessed.

Method

Participants

The total sample consisted of 635 Mexicans (62.5% females), who did not belong to any indigenous community or immigrant group, assessing one of three minorities (indigenous Mexicans, n = 200; US immigrants, n = 216; or Honduran immigrants, n = 219), and selected by non-probability sampling from social networks. Participants were between 18 and 68 years old with a mean age of 29.07 (SD = 11.37) and resided in different states of Mexico: the majority in Jalisco (70.1%), Baja California Norte (14%), Puebla (6%), Mexico City (4.7%), and others (5.5%). Regarding marital status, 71% of the participants were single, 16.2% were married, 7.6% were cohabiting, 4.3% were separated or divorced, and 0.9% were widowed. Regarding the main activity, 53.1% of the participants were students, 40.8% were workers, 3.3% were housewives, 1.7% were retired, and 1.1% indicated other activity. The majority (83.6%) of the participants had university studies, 15.4% had non-university higher education and 0.9% had secondary education.

Variables and instruments

Participants were randomly assigned to the evaluation of one of the three different targets (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, or Honduran immigrants) in a series of variables following an intergroup design. No intergroup differences were found in the sociodemographics of the participants allocated to the different groups (ps > .20). Reliability coefficients using Cronbach's alpha of all measures are shown in Table 2.

Stereotypes

Four stereotype dimensions of morality, sociability, competence (from Leach et al., 2007, adapted to Spanish by López-Rodríguez et al., 2013), and immorality (adapted from Sayans-Jiménez et al., 2018) were measured. Participants indicated, as non-indigenous or non-immigrants, how many people from a target group (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, or Honduran immigrants) had various characteristics. The scale was composed of 12 items, three items for each dimension: morality (i.e., sincere, honest, and trustworthy), immorality (i.e., treacherous, false, and malicious), sociability (i.e., friendly, warm, and nice), and competence (i.e., skillful, competent, and intelligent). The response scale was Likert-type with a range between 1 and 7 (1 = none, 2 = almost none, 3 = a few; 4 = half, 5 = many, 6 = almost all, and 7 = all). Higher scores on each subscale revealed a more stereotypical view as moral, immoral, sociable, or competent of the group assessed. Then, they were asked to evaluate their own group (i.e., Mexicans, when assessing immigrants, or non-indigenous Mexicans when assessing indigenous Mexicans) using the same procedure.

Outgroup realistic and symbolic threat

Participants indicated the extent to which they felt that the target group (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, or Honduran immigrants) endangered certain issues using the Outgroup Threat Perception Scale (Navas et al., 2012). The scale consisted of 13 items: 9 referred to realistic threat (e.g., access to health care) and 4 to symbolic threat (e.g., culture) on a Likert-type response format ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Higher scores indicated greater perceived (realistic or symbolic) threat.

Quantity of contact

It was measured with six items from Cervantes et al. (2019), asking about the amount of contact with the specific group (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, or Honduran immigrants) in different places (e.g., NGOs, work). The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Higher scores indicated more contact with the outgroup.

Perceived discrimination against the outgroup

It was measured with four items from Schmitt et al. (2002) adapted to the specific target group (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, or Honduran immigrants). Participants indicated the extent they agreed with some statements regarding how discriminated they perceived the outgroup was (e.g., they are victims of discrimination in Mexican society). The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Higher scores indicated a greater perception of the specific target group discrimination.

Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to the evaluation of one of three target groups (i.e., indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, or Honduran immigrants) following an ex post facto retrospective design of three groups. Participants completed questionnaires through an online form disseminated in student social networking groups in different Mexican states requesting their participation and, optionally, their collaboration in sending the questionnaire to other potential participants following a snowball technique. The questionnaire stated the objective of the study, the responsible person, the anonymous and confidential treatment of the data obtained, the voluntary nature of the participation, and the explicit consent of the participants. It lasted approximately 20 min. All participated voluntarily and did not receive any incentive or remuneration. This study was part of a larger project on new proposals for the improvement of intergroup relations based on morality that had the approval of the Bioethics Committee for Human Research of the authors’ university.

Results

Stereotypes about minority groups (outgroups) and Mexicans (ingroup)

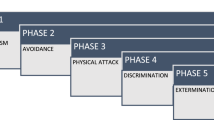

In order to compare the stereotypes attributed to the three minority groups (the outgroups) with those attributed to MexicansFootnote 1 (the ingroup) in the dimensions of (im)morality, sociability, and competence, we conducted mixed-ANOVAs with the outgroup and ingroup perception as within-group factors and the target group as an intergroup factor for each stereotype dimension. Figure 1 shows the perception of participants in all the stereotype dimensions about the outgroup and the ingroup.

The analysis revealed that there was a significant multivariate effect of the ingroup-outgroup comparison on perceived morality, Wilks’ Λ = 0.92, F(1, 632) = 57.92, p < .001, ηp2 = .084; as well as a significant effect of the two-way interaction with the target group, Wilks’ Λ = 0.79, F(2, 632) = 82.52, p < .001, ηp2 = .207. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni tests showed that participants attributed more morality to their own group (Mexicans) compared to Honduran immigrants (p = .019, ηp2 = .009). That is, they perceived that there were more Mexicans being moral than Honduran immigrants. The opposite happened when comparing Mexicans with indigenous Mexicans, considering that more indigenous Mexicans are moral compared to Mexicans (p < .001, ηp2 = .249). There were no differences between the morality attributed to US immigrants and Mexicans (p = .530, ηp2 = .001).

There was a significant multivariate effect of the ingroup-outgroup comparison in perceived sociability, Wilks’ Λ = 0.96, F(1, 632) = 26.32, p < .001, ηp2 = .040; as well as a significant effect of the two-way interaction with the target group, Wilks’ Λ = 0.78, F(2, 632) = 89.43, p < .001, ηp2 = .221. Pairwise comparisons showed that participants attributed more sociability to Mexicans compared to US immigrants (p < .001, ηp2 = .142) and Honduran immigrants (p < .001, ηp2 = .068). That is, they perceived that there were more Mexicans being sociable than US or Honduran immigrants. The opposite happened when comparing Mexicans with indigenous Mexicans who were considered much more sociable (p < .001, ηp2 = .086).

There was not a significant multivariate effect of the ingroup-outgroup comparison in perceived competence, Wilks’ Λ = 0.99, F(1, 632) = 2.52, p = .113, ηp2 = .004; but the two-way interaction with the target group was significant, Wilks’ Λ = 0.89, F(2, 632) = 40.62, p < .001, ηp2 = .114. Pairwise comparisons showed that participants attributed more competence to Mexicans than to Honduran immigrants (p < .001, ηp2 = .025), considering that there were more Mexicans competent than Honduran immigrants. The opposite happened when comparing Mexicans with indigenous Mexicans, considering that there were more indigenous Mexicans competent compared to Mexicans (p < .001, ηp2 = .092). There were no differences in perceived competence between US immigrants and Mexicans (p = .116, ηp2 = .004).

Finally, there was a significant multivariate effect of the ingroup-outgroup comparison in perceived immorality, Wilks’ Λ = 0.62, F(1, 632) = 382.82, p < .001, ηp2 = .377, as well as the two-way interaction with the target group, Wilks’ Λ = 0.84, F(2, 632) = 61.91, p < .001, ηp2 = .164. Pairwise comparisons showed that participants perceived that fewer indigenous Mexicans (p < .001, ηp2 = .380), US immigrants (p < .001, ηp2 = .108), and Honduran immigrants (p < .001, ηp2 = .039) were immoral (i.e., treacherous, false, and malicious) compared to the Mexicans. Means in perceived immorality of Mexicans were between points 3 (few) and 4 (half) on the Likert scale, revealing a critical perception about the ingroup.

To summarize, participants had an extremely positive image of indigenous Mexican people in terms of stereotypes, considering that many of them are moral, sociable, and competent, and hardly less immoral compared to the ingroup. Participants had a more negative view regarding Honduran immigrants, who were seen as less moral, sociable, and competent than Mexicans. On the other hand, US immigrants were perceived as less sociable and just as moral and competent as Mexicans. Interestingly, participants considered that there are more immoral Mexicans compared to all minority groups.

Comparing minority groups

In order to analyze the differences in the evaluation of the three different minority groups, we conducted a MANOVA with the target group as independent variable and the stereotype dimensions (i.e., morality, sociability, competence, and immorality), perceived threat, perceived discrimination and quantity of contact as dependent variables.

The analysis yielded a significant multivariate effect of the target group, Wilks’ Λ = 0.37, F(16, 1250) = 38.63, p < .001, ηp2 = .390. The univariate effects were significant for perceived morality, F(2, 632) = 46.11, p < .001, ηp2 = .127; sociability, F(2, 632) = 35.95, p < .001, ηp2 = .102; competence, F(2, 632) = 33.15, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.095; and immorality, F(2, 632) = 28.21, p < .001, ηp2 = .082. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni tests showed that indigenous Mexicans were the best evaluated group in all stereotype dimensions: participants perceived that there were more moral, competent and sociable, and less immoral indigenous Mexicans than US and Honduran immigrants (ps < .001). US immigrants were considered more competent than Hondurans (p < .001), but both groups were perceived as equally moral (p = .978), sociable (p = .958), and immoral (p = .077).

The analysis also revealed a significant univariate effect of the target group on perceived realistic threat, F(2, 632) = 15.82, p < .001, ηp2 = .048, perceived symbolic threat, F(2, 632) = 7.85, p < .001, ηp2 = .024, perceived discrimination, F(2, 632) = 268.96, p < .001, ηp2 = .460, and quantity of contact, F(2, 632) = 52.35, p < .001, ηp2 = .142. Indigenous Mexicans elicited less realistic threat than US and Honduran immigrants (ps < .001). There was no difference between the realistic threat generated by US and Honduran immigrants (p = .472). However, US immigrants elicited more symbolic threat than indigenous Mexicans (p = .011) and Honduran immigrants (p < .001). There was no difference between the symbolic threat generated by indigenous Mexicans and Honduran immigrants (p = 1.000). Indigenous Mexicans were perceived as the most discriminated group (ps < .001), and more discrimination was perceived toward Honduran immigrants than toward US immigrants (p < .001). Honduran immigrants were the group with whom participants had the least contact (ps < .001). Contact with indigenous people and US immigrants did not differ (p = 1.000). Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics of stereotype dimensions, perceived threat (realistic and symbolic), perceived discrimination, and quantity of contact toward the different minority groups.

Associations of stereotypes with perceived threat, discrimination, and contact

Table 4 shows the correlations of stereotype dimensions with perceived threat, perceived discrimination, and quantity of contact. Perceiving that more people within the outgroup are moral, sociable, and competent was associated with less realistic threat when evaluating US and, especially, Honduran immigrants. Perceiving that more people within these groups are immoral was associated with a greater realistic threat. However, most stereotype dimensions were not associated with perceiving realistic threat from indigenous Mexicans. Stereotypes were associated with symbolic threat in all groups, except immorality in the indigenous group. Only perceived competence was positively associated with a higher perception of discrimination among those participants who evaluated indigenous Mexicans and Honduran immigrants. The more competent these groups were perceived, the higher the recognition of their discrimination. Perceived sociability of indigenous Mexicans was also positively associated with greater perceived discrimination against that social group. Stereotype dimensions were not associated with quantity of contact in this study.

Given the well-established theoretical association between stereotypes and perceived threat, it is striking that the correlations between stereotypes and realistic threat seem to vary depending on the minority group assessed. In order to test whether the target group could moderate the association between stereotypes and perceived realistic threat, we conducted analyses to verify the two-way interaction using the PROCESS macro of Hayes (2018) for SPSS. Morality (X1), immorality (X2), sociability (X3), and competence (X4) were specified as predictors of realistic threat (Y). The target group (W) with three levels (indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants) was set as a moderating variable. We established an indicator coding with indigenous Mexicans as the reference group for comparisons.

The analysis confirmed that the relationship between morality and realistic threat varied depending on the target group when comparing indigenous Mexicans with Honduran immigrants, B = -0.16, SE = 0.08, p = .029, CI 95% = -0.3165, -0.0047, but there was no difference when comparing indigenous Mexicans with US immigrants, B = -0.09, SE = 0.08, p = .299, CI 95% = -0.2510, 0.0773. Conditional effects showed that perceived morality was negatively associated with realistic threat in the US group, B = -0.24, SE = 0.08, p = .001, CI 95% = -0.3939, -0.0947, and even more in the Honduran group, B = -0.31, SE = 0.07, p < .001, CI 95% = -0.4551, -0.1810, but it was not significant when evaluating indigenous Mexicans, B = -0.15, SE = 0.08, p = .061, CI 95% = -0.3219, 0.0070 (see Fig. 2, Panel A).

The relationship between immorality and realistic threat also varied depending on the target group when comparing indigenous Mexicans to US immigrants, B = 0.19, SE = 0.08, p = .018, CI 95% = 0.0330, 0.3537, and to Honduran immigrants, B = 0.22, SE = 0.07, p = .002, CI 95% = 0.0780, 0.3598. Conditional effects showed that perceived immorality was positively associated with realistic threat in the US group, B = 0.16, SE = 0.06, p = .013, CI 95% = 0.0326, 0.2855, and in the Honduran group, B = 0.18, SE = 0.05, p < .001, CI 95% = 0.0842, 0.2850, but not in the indigenous group, B = -0.03, SE = 0.05, p = .497, CI 95% = -0.1336, 0.0649 (see Fig. 2, Panel B).

The relationship between competence and realistic threat varied depending on the target group when comparing indigenous Mexicans with Honduran immigrants, B = -0.17, SE = 0.08, p = .027, CI 95% = -0.3218, -0.0187, but not when comparing indigenous Mexicans with US immigrants, B = -0.08, SE = 0.08, p = .313, CI 95% = -0.2521, 0.0811. Competence was negatively associated with realistic threat in the Honduran group, B = -0.13, SE = 0.06, p = .035, CI 95% = -0.2524, -0.0092, but not in the indigenous group, B = 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = .578, CI 95% = -0.1000, 0.1790, nor in US group, B = -0.05, SE = 0.07, p = .533, CI 95% = -0.1911, 0.0990 (see Fig. 3).

The relationship between sociability and realistic threat did not vary depending on the target group either when comparing indigenous Mexicans with US immigrants, B = -0.04, SE = 0.08, p = .604, CI 95% = -0.1933, 0.1125; nor when comparing indigenous Mexicans with Honduran immigrants, B = -0.15, SE = 0.08, p = .056, CI 95% = -0.3089, 0.0042. Sociability was only marginally associated with realistic threat in the indigenous group, B = 0.14, SE = 0.07, p = .052, CI 95% = -0.0013, 0.2858, and neither in the US group, B = 0.10, SE = 0.07, p = .129, CI 95% = -0.0299, 0.2337, nor in the Honduran group, B = -0.01, SE = 0.07, p = .893, CI 95% = -0.1577, 0.1375.

No interaction of the target group with symbolic threat or perceived discrimination was significant.

Discussion

Mexico is a country with wide ethnic diversity. Particularly relevant is the multiculturalism produced by European-indigenous miscegenation. Currently, there are two large groups: the majority society, which shares mixed customs resulting from the miscegenation of colonization, and also the indigenous communities that have mainly maintained their native culture. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a remarkable absence of studies that compare the Mexicans’ perceptions of some minorities such as indigenous Mexicans, and US, and Honduran immigrants, a comparison that can offer fundamental keys. Specifically, there are no systematic studies comparing the perceptions of these minority groups in the four stereotype dimensions of morality, sociability, competence, and immorality, being (im)morality primary for social judgments. Methodologically, previous research has usually focused only on analyzing stereotypes about minority groups, but not in the comparison with the evaluator's group, losing part of the picture of the dynamic process of social perception. At the theoretical level, the relationship between stereotypes and threat has been studied previously, but not serious consideration has been given to the fact that this relationship might vary depending on the minority assessed, and, accordingly, the characteristics of the target are a crucial factor when determining the association between stereotypes and perceived threat.

Our first aim was to identify the stereotypes, threat, and discrimination perceptions of Mexicans regarding indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants, as well as the amount of contact they had with these groups and the relationship between these variables.

Outgroup-ingroup stereotypes

Results showed that participants considered indigenous Mexicans as more moral, sociable, competent, and less immoral than themselves. To understand this, it is necessary to consider that indigenous people in Mexico live in marginal conditions (e.g., Gracia & Horbath, 2019) and the Mexican society itself recognizes that the rights of this group are not respected (Gutiérrez & Valdés, 2015). Therefore, a possible explanation is that the image of undeserved exclusion of indigenous communities may lead non-indigenous Mexicans to consider themselves partly responsible for such a situation. In addition, it is likely that the participants of the study considered the indigenous people in Mexico as the ‘original’ Mexicans (Echeverría, 2016), rich in customs and traditions, favoring the vision they have for this group.

The opposite happened with Honduran immigrants, seen as less moral, competent, and sociable than Mexicans. To understand these results, we can consider that the lack of knowledge about this group that has recently been the object of public opinion and the broad emphasis that the media has placed on the migrant caravans may have elicited negative stereotypes among Mexicans. It has been previously reported that Honduran immigrants are one of the groups of foreigners who are least trusted by Mexicans (Caicedo & Morales, 2015).

US immigrants were perceived as moral and competent as Mexicans, but less sociable. The sociability image of Mexicans (both indigenous and non-indigenous) may be congruent with Hofstede’s individualism/collectivism dimension (1980). According to Hofstede (2011), social ties in individualistic cultures are laxer than in collectivistic cultures where there is a major focus on social harmony and “relationship prevails over task” (p. 11). Being Mexico a much more collectivistic country than the US (Kyoon Yoo et al., 2006), Mexicans’ social behavior may be characterized by more intense and deeper contact and communication (related to sociable traits) than in individualistic countries such as the US. This orientation may illuminate why US immigrants are perceived by Mexican participants as less sociable than Mexicans. Previously, similar results were found in other Latin American contexts (i.e., Brazil) in which one's own group was not better evaluated in all aspects (i.e., work-related values), but in those referring to sociability (i.e., personal warmth, social agreeableness). Even the stereotypes of the Mexicans fall on aspects of sociability such as being friendly and kind (e.g., Ramírez-Esparza et al., 2009).

This image of greater sociability of Mexicans could also be partly due to a compensation effect (Kervyn et al., 2010) since Mexicans perceived themselves as the most immoral group of all. Participants perceived that a few or even half of Mexicans (ingroup) were immoral. This finding opens new paths in order to understand how this perception can affect the collective identity and self-esteem of Mexicans. This study not only reveals ideas about the perception of minorities in Mexico but also about the view of Mexicans about themselves.

Comparing minorities in Mexico

Indigenous Mexicans were the best-evaluated group in the stereotype dimensions as they were perceived as more moral, sociable, competent, and less immoral than US and Honduran immigrants (Hypothesis 1). This was expected because participants may recategorize indigenous and non-indigenous (Gaertner et al., 1993) in the same category (i.e., Mexicans) and thus favor their own ingroup (Turner et al., 1979), possibly because of the cultural contribution that is recognized to the different indigenous communities and because indigenous Mexicans are perceived unjustly treated. US and Honduran immigrants were perceived as equally moral, sociable, and immoral; however, Mexicans found US immigrants more competent than Hondurans, probably linked to the higher status of the former (Fiske et al., 2002). Since competence is defined by the ability to achieve goals, it may be that the socioeconomic status of Honduran immigrants at a broad disadvantage compared to US immigrants is related to their being perceived as a less competent group of immigrants.

Indigenous Mexicans were the group that elicited the least realistic threat (Hypothesis 2). We expected this result considering that realistic threat involves competition for resources that are limited in which indigenous Mexicans, as a group, have been disadvantaged (e.g., health care, Juárez-Ramírez et al., 2014, access to the educational system, Köster, 2016; job conditions; Vázquez-Parra, 2020). On the other hand, Mexicans perceived US immigrants as the most symbolically threatening (Hypothesis 3). Considering that this type of threat contemplates cultural factors and values, Mexicans may feel more threatened by US people, with whom they differ more in aspects such as language and religion, which have exacerbated their historically complex relationships (Eller & Abrams, 2003).

As expected, indigenous Mexicans were perceived as the most discriminated group (Hypothesis 4), which is consistent with previous findings reflecting that this group is the most discriminated in the country (Gutiérrez & Valdés, 2015). Similarly, previous literature (Caicedo & Morales, 2015) indicated that Honduran immigrants were perceived as more discriminated against than US immigrants, which coincides with the results of this study. Indigenous Mexicans were the best evaluated group, both in terms of morality, sociability, and competence and in recognizing that indigenous people continue to be the most discriminated group. This is especially interesting in a country with a history of European-indigenous intermarriage in which, on the one hand, the majority society shares elements of both cultures, while on the other hand, the people who comprise indigenous communities maintain to a greater extent indigenous customs (e.g., native languages). Given this, it is convenient to consider the different representations of the indigenous (Benítez, 1968) in the social imaginary, admiring the “dead” indigenous (i.e., pre-Hispanic, admired for their cultural richness and honored in museums), but despising the “alive” indigenous (i.e., the real and contemporary with social difficulties). These representations, together with previous literature and our own results, suggest considering that Mexicans appreciate the attributes of indigenous Mexicans who bring great cultural richness to the country while recognizing the social disadvantage in which they live.

Regarding contact, we found that the lowest levels of contact were with Honduran immigrants (Hypothesis 5), probably due to their transitory condition in the country in which they are not present in the evaluated areas (e.g., schools, NGOs, work). Findings regarding less contact with Honduran immigrants should be interpreted considering their different living conditions in the country. The social conditions of Honduran immigrants in Mexico affect the possibility of being in contact with Mexicans, as they are generally marginalized, sometimes even in situations of humanitarian emergency, and are considered “in transit” to the United States. In fact, the participants of this study reported that the largest contact with Hondurans was on the streets, whereas they reported having contact with indigenous Mexicans and US immigrants also in other places (i.e., educational centers, jobs, neighborhoods). It seems that indigenous Mexicans and US immigrants have more general contact with the Mexican majority. This was expected because indigenous Mexicans are the largest minority and have always been in the country, therefore, it would be more common to meet with them in different contexts. On the other hand, US immigrants are also settled in Mexico longer (compared to Hondurans) and with substantial differences such as higher status and greater economic possibilities that allow them to have a good level of housing, establish ties with their community of neighbors, and not be in transitory conditions. These conditions would allow them to have frequent contact in Mexico.

Stereotypes and perceived threat

Our second aim was to explore whether the relationship between stereotypes and perceived threat varied depending on the ethnic minority assessed. The importance of the relationship between stereotypes and threat had previously been demonstrated (Stephan et al., 2015), and it is especially linked to morality (e.g., Brambilla et al., 2012). This relationship had recently been studied in Honduran immigrants in Mexico (Vázquez-Flores et al., 2022), but without considering the theoretical contribution of including other stereotype dimensions (i.e., sociability, competence) in the outgroup evaluation, nor comparing whether that relationship varied depending on the group evaluated. The results of the present study showed that the relationship between stereotypes, mainly morality, and immorality –which are crucial in social judgments– and perceived realistic threat, but not symbolic, varied depending on the ethnic minority assessed. Specifically, morality was negatively associated, and immorality was positively associated with realistic threat in the US immigrant group, and even more in the Honduran immigrant group, but these relationships were not significant in the indigenous group, which provoked the least realistic threat. Competence was negatively associated with realistic threat only in the Honduran group, while the relationship between sociability and realistic threat did not vary between groups.

Interestingly, the strength of stereotypes as they relate to threat is more intense in groups that may be more unfamiliar and more negatively stereotyped, such as Honduran immigrants, due to their more transitory and less rooted nature in the Mexican context. Hondurans are relatively a new group in Mexico, and the first formation of impressions of Mexicans toward them may occur according to what they have seen in mass media (e.g., Manetto, 2021). These first pictures of Hondurans, as large groups of people trying to cross the border to Mexico forming caravans, might have also become threatening due to the concern of Mexicans for not having enough resources for that amount of people. On the other hand, the Mexican majority is much more familiar with indigenous Mexicans (i.e., share the nationality with them, recognize the richness of their traditions, and maintain greater contact in different contexts). Likewise, US immigrants are also a known group with whom contact has been maintained for a long time; thus, stereotypes toward these groups are more consolidated than toward Hondurans. One possible explanation is that the relationship between stereotypes and realistic threat may be stronger among unknown and undervalued groups, as is the case of Hondurans, whose image is possibly shaped by the mass media, and therefore stereotypes would provide more valuable information to protect the ingroup from possible threats. It seems that the association between stereotypes and threat is more common when stereotypes are the only source of information for the feeling of threat. Again, the predominance of (im)morality (e.g., Brambilla et al., 2012) in its relationship with other variables related to prejudice (i.e., realistic threat) is shown.

Limitations, contributions, and future directions

The study is not free of limitations. With a non-probability sampling, the results cannot be generalized. Specifically, the sample is mostly from Jalisco, with university studies, and half of them are students. It is necessary to interpret the results with caution because they may reflect a very particular perspective, given that only a minority of people in Mexico have access to university education. The online format and data collection through social networks have prevented to have access to a more representative sample of Mexican society. Future studies should include using different data collection procedures and extending to a more representative sample. Additionally, with a cross-sectional and non-experimental design, we cannot make any assumption of causality or directionality and future studies could verify under which conditions (im)moral stereotypes are predictive of perceived realistic threat. Moreover, although this study includes conditions that reduce social desirability (guaranteeing the privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality of the participant's responses, and that the researchers were not present in person when the participant responded, Nederhof, 1985); it does not completely eliminate the possibility that participants could have given socially desirable answers, which is a limitation to be considered.

Nevertheless, despite of the limitations, this study can be considered pioneering because it includes three minority groups that have not often been jointly studied in Mexico. Specifically, this study has allowed us to learn about the stereotype, threatening and discriminatory perceptions of the Mexican majority toward indigenous Mexicans, US immigrants, and Honduran immigrants, as well as the amount of contact they had with these groups. Moreover, including the evaluation of ingroup stereotypes has made it possible to broaden the consideration of Mexicans' own evaluation when assessing other groups. This confirms the need for further research on the perceptions of the Mexican majority toward minority groups in interaction with their own perception. It would be very enriching to consider other variables in further studies (e.g., emotions, behavioral tendencies) that would allow us to expand the psychosocial literature in the Mexican context. Along these lines, we encourage future experimental and longitudinal studies to complement this research.

In addition, this study is also contributing to revealing that the relationships between the relevant psychosocial variables (i.e., stereotypes and threat) may vary depending on the groups evaluated. As for the international interest of these findings, we consider that they may contribute to unveiling whether specific psychosocial processes may be universal and work regardless of the cultural context, and so, contribute to a more representative psychological science of the human condition (see Rad et al., 2018). Concerning the new theoretical findings, future research should confirm that the specific relationship between perceived morality and threat may depend on the minority group assessed in other contexts, as well as decode the psychological processes and social dynamics that may account for such differences.

Our results can contribute to the development of policies that favor the inclusion of the most disadvantaged groups in the country, both the autochthonous (i.e., indigenous) and the most disadvantaged immigrants (i.e., Hondurans). Specifically, we intend these results to be considered for the development of intervention programs to improve the quality of life and integration of disadvantaged groups. Social institutions should design intervention programs that provide the necessary conditions to satisfy their right to education, employment, and decent living conditions, as well as adopt specific strategies according to the target group. Specifically, we propose to disseminate the disparity between the positive perception of indigenous Mexicans and the social reality in which they live, and thus raise awareness of the importance of eliminating the structural barriers that prevent the reduction of social inequalities. In addition, this study has shown the strong relationship between stereotypes and threat in the Honduran immigrant group, thus social programs should consider increasing the perception of morality and competence of this group.

Data availability

Dataset is available on reasonable request.

Notes

The term Mexicans refers to the Mexican non-indigenous majority.

References

Alexander, R. (1985). A biological interpretation of moral systems. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 20(1), 3–20.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The Nature of Prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

Ashmore, R. D., & Del Boca, F. K. (1981). Conceptual Approaches to Stereotypes and Stereotyping. In D. L. Hamilton (Ed.), Cognitive Processes in Stereotyping and Intergroup Behavior (pp. 1–35). Erlbaum.

Ball, P. (1983). Stereotypes of Anglo-Saxon and non-Anglo-Saxon accents: Some exploratory Australian studies with the matched guise technique. Language Sciences, 5(2), 163–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0388-0001(83)80021-7

Benítez, F. (1968). Los indios de México (Vol. 3) [The Indians of Mexico]. Era.

Brambilla, M., Hewstone, M., & Colucci, F. P. (2013). Enhancing moral virtues: Increased perceived outgroup morality as a mediator of intergroup contact effects. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16, 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212471737

Brambilla, M., Rusconi, P., Sacchi, S., & Cherubini, P. (2011). Looking for honesty: The primary role of morality (vs. sociability and competence) in information gathering. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41(2), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.744

Brambilla, M., Sacchi, S., Rusconi, P., Cherubini, P., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2012). You want to give a good impression? Be honest! Moral traits dominate group impression formation. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51(1), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02011.x

Brambilla, M., & Leach, C. W. (2014). On the importance of being moral: The distinctive role of morality in social judgment. Social Cognition, 32(4), 397–408. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2014.32.4.397

Caicedo, M., & Morales, A. (2015). Imaginarios de la migración internacional en México: una mirada a los que se van y a los que llegan: Encuesta Nacional de Migración [Imaginaries of international migration in Mexico: a look at those who leave and those who arrive: National Migration Survey]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Cervantes, L., Navas, M., & Cuadrado, I. (2019). Contacto intergrupal y actitudes en bibliotecas públicas: un estudio con usuarios marroquíes y españoles en Barcelona y Almería [Intergroup contact and attitudes in public libraries: A study with Moroccan and Spanish users in Barcelona and Almería]. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 42(1), e227. https://doi.org/10.3989/redc.2019.1.1581

Díaz-Loving, R., & Draguns, J. G. (1999). Culture, meaning, and personality in Mexico and in the United States. In Y.-T. Lee, C. R. McCauley, & J. G. Draguns (Eds.), Personality and Person Perception Across Cultures (pp. 103–126). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Echeverría, R. (2016). Estereotipos y discriminación hacia personas indígenas mayas: su expresión en las narraciones de jóvenes de Mérida Yucatán [Stereotypes and discrimination toward Mayan indigenous people: their expression in the narratives of young people from Mérida Yucatán]. Aposta. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 71, 95–127. https://www.redalyc.org/journal/4959/495952433004/html/

El-Dash, L. G., & Busnardo, J. (2001). Perceived in-group and out-group stereotypes among Brazilian foreign language students. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11(2), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/1473-4192.00015

Eller, A., & Abrams, D. (2003). ‘Gringos’ in Mexico: Cross-sectional and longitudinal effects of language school-promoted contact on intergroup bias. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 6(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430203006001012

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Gaertner, S. L., Dovidio, J. F., Anastasio, P. A., Bachman, B. A., & Rust, M. C. (1993). The common ingroup identity model: Recategorization and the reduction of intergroup bias. European Review of Social Psychology, 4(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779343000004

Gilmour, J. (2015). Formation of stereotypes. Behavioural Sciences Undergraduate Journal, 2(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.29173/bsuj307

Gracia, M. A., & Horbath, J. E. (2019). Exclusión y discriminación de indígenas en Guadalajara, México [Discrimination and exclusion of indigenous people in Guadalajara, Mexico]. Perfiles Latinoamericanos, 27(53), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.18504/pl2753-011-2019

Gutiérrez, N., & Valdés, L. M. (2015). Ser indígena en México: raíces y derechos; Encuesta Nacional de Indígenas [Being indigenous in Mexico: roots and rights; National Survey of Indigenous]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage.

Jost, J. T., & Banaji, M. (1994). The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology, 33, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.1994.tb01008.x

Juárez-Ramírez, C., Márquez-Serrano, M., Salgado de Snyder, N., Pelcastre-Villafuerte, B. E., Ruelas-González, M. G., & Reyes-Morales, H. (2014). La desigualdad en salud de grupos vulnerables de México: adultos mayores, indígenas y migrantes [Inequality in health of vulnerable groups in Mexico: older adults, indigenous people and migrants]. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 35(4), 284–290. https://www.scielosp.org/article/rpsp/2014.v35n4/284-290

Judd, C., James-Hawkins, L., Yzerbyt, V., & Kashima, Y. (2005). Fundamental dimensions of social judgement: Understanding the relations between judgements of competence and warmth. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 899–913. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.899

Kervyn, N., Yzerbyt, V., Demoulin, S., & Judd, C. (2008). Competence and warmth in context: The compensatory nature of stereotypic views of national groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 1175–1183. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.526

Kervyn, N., Yzerbyt, V., & Judd, C. M. (2010). Compensation between warmth and competence: Antecedents and consequences of a negative relation between the two fundamental dimensions of social perception. European Review of Social Psychology, 21(1), 155–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546805.2010.517997

Koomen, W., & Dijker, A. J. (1997). Ingroup and outgroup stereotypes and selective processing. European Journal of Social Psychology, 27, 589–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199709/10)27:5%3c589::AID-EJSP840%3e3.0.CO;2-Y

Köster, A. J. (2016). Educación asequible, accesible, aceptable y adaptable para los pueblos indígenas en México: Una revisión estadística [Affordable, accessible, acceptable and adaptable education for indigenous peoples in Mexico: A statistical review]. Alteridad. Revista de Educación, 11(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.17163/alt.v11n1.2016.03

Kyoon Yoo, D., Subba Rao, S., & Hong, P. (2006). A comparative study on cultural differences and quality practices – Korea, USA, Mexico, and Taiwan. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management, 23(6), 607–624. https://doi.org/10.1108/02656710610672452

Leach, C. W., Ellemers, N., & Barreto, M. (2007). Group virtue: the importance of morality (vs. competence and sociability) in the positive evaluation of in-groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(2), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.234

Lemmer, G., & Wagner, U. (2015). Can we really reduce ethnic prejudice outside the lab? A meta-analysis of direct and indirect contact interventions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 45(2), 152–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2079

Lizárraga, O. (2008). La inmigración de jubilados estadounidenses en México y sus prácticas transnacionales. Estudio de caso en Mazatlán, Sinaloa y Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur [Immigration of American retirees in Mexico and their transnational practices. Case study in Mazatlán, Sinaloa and Cabo San Lucas, Baja California Sur]. Migración y Desarrollo, 11, 97–117. https://doi.org/10.35533/myd.0611.olm

López-Rodríguez, L., Cuadrado, I., & Navas, M. (2013). Aplicación extendida del Modelo del Contenido de los Estereotipos (MCE) hacia tres grupos de inmigrantes en España [Extended application of the Stereotype Content Model (SCM) to three groups of immigrants in Spain]. Estudios de Psicología, 34(2), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1174/021093913806751375

López-Rodríguez, L., Zagefka, H., Navas, M., & Cuadrado, I. (2014). Explaining majority members’ acculturation preferences for minority members: A mediation model. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.07.001

Manetto, F. (2021). Una caravana de miles de migrantes avanza firme por Guatemala y se dirige hacia México [Caravan of thousands of migrants moves steadily through Guatemala and heads toward Mexico]. El País. Retrieved from https://elpais.com/internacional/2021-01-17/una-caravana-de-miles-de-migrantes-avanza-imparable-por-guatemala-y-se-dirige-hacia-mexico.html

Meza-González, L., & Orraca-Romano, P. (2022). Análisis del ingreso laboral de los jóvenes estadounidenses en México [Analysis of the labor income of young Americans in Mexico]. Migraciones Internacionales, 13, rmiv1i12478. https://doi.org/10.33679/rmi.v1i1.2478

Morrison, K. R., & Ybarra, O. (2008). The effects of realistic threat and group identification on social dominance orientation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(1), 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.12.006

Muñiz, C., Serrano, F. J., Aguilera, R. E., & Rodríguez, A. (2010). Estereotipos mediáticos o sociales. Influencia del consumo de televisión en el prejuicio detectado hacia los indígenas mexicanos [Media or social stereotypes. Influence of television consumption on the prejudice detected toward indigenous Mexicans]. Global Media Journal México, 7(14), 93–113. https://gmjmexico.uanl.mx/index.php/GMJ_EI/article/view/13

Nájera-Aguirre, J. (2019). La Caravana migrante en México: origen, tránsito y destino deseado [The migrant Caravan in Mexico: origin, transit and desired destination]. Coyuntura Demográfica, 15, 67–74. http://coyunturademografica.somede.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/najera.pdf

National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). (2020). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020 [Population and Housing Census 2020]. https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/

Navarrete, F. (2004). Las relaciones inter-étnicas en México [Inter-ethnic relations in Mexico]. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Navas, M., Cuadrado, I., & López-Rodríguez, L. (2012). Fiabilidad y evidencias de validez de la Escala de Percepción de Amenaza Exogrupal (EPAE) [Reliability and evidence of validity of the Outgroup Threat Perception Scale (OTPS)]. Psicothema, 24(3), 477–482. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/727/72723439022.pdf

Nederhof, A. J. (1985). Methods of coping with social desirability bias: A review. European Journal of Social Psychology, 15(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420150303

Oldmeadow, J., & Fiske, S. T. (2007). System-justifying ideologies moderate status = competence stereotypes: Roles for belief in a just world and social dominance orientation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(6), 1135–1148. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.428

Oldmeadow, J. A., & Fiske, S. T. (2010). Social status and the pursuit of positive social identity: Systematic domains of intergroup differentiation and discrimination for high- and low-status groups. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 13(4), 425–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209355650

Palma-Mora, M. (2009). Entre el placer y el delito: Estadounidenses infractores en la Ciudad de México, 1910–1913 [Between pleasure and crime: American offenders in Mexico City, 1910–1913]. Signos Históricos, 11(21), 104–135. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1665-44202009000100005&lng=es&tlng=es

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 751–783. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 922–934. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.504

Rad, M. S., Martingano, A. J., & Ginges, J. (2018). Toward a psychology of Homo sapiens: Making psychological science more representative of the human population. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(45), 11401–11405. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721165115

Ramírez-Esparza, N., Mehl, M. R., Álvarez-Bermúdez, J., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2009). Are Mexicans more or less sociable than Americans? Insights from a naturalistic observation study. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.09.002

Rios, K., Sosa, N., & Osborn, H. (2018). An experimental approach to intergroup threat theory: manipulations, moderators, and consequences of realistic vs. symbolic threat. European Review of Social Psychology, 29(1), 212–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2018.1537049

Rodríguez, E., & Cobo, S. (2012). Extranjeros Residentes en México. Una aproximación cuantitativa con base en los registros administrativos del INM [Foreigners Resident in Mexico. A quantitative approximation based on INM administrative records]. Centro de Estudios Migratorios - Instituto Nacional de Migración. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1094.4801

Ruíz-Lagier, V., & Varela-Huerta, A. (2020). Caravanas de migrantes y refugiados en tránsito por México: el éxodo de jóvenes hondureños que buscan, migrando, preservar la vida [Caravans of migrants and refugees in transit through Mexico: the exodus of young Hondurans who seek, migrating, to preserve life]. EntreDiversidades, 7(1), 92–129. https://doi.org/10.31644/ed.v7.n1.2020.a04

Rusconi, P., Sacchi, S., Brambilla, M., Capellini, R., & Cherubini, P. (2020). Being honest and acting consistently: Boundary conditions of the negativity effect in the attribution of morality. Social Cognition, 38(2), 146–178. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2020.38.2.146

Sayans-Jiménez, P., Cuadrado, I., Blanc, A., Ordóñez-Carrasco, J., & Rojas, A. (2018). Morality Stereotype Content Scale (MSCS): Rasch analysis and evidences of validity. Ceskoslovenska Psychologie, 62(4), 366–381. http://cspsych.psu.cas.cz/result.php?id=1025

Sayans-Jiménez, P., Rojas, A., & Cuadrado, I. (2017). Is it advisable to include negative attributes to assess the stereotype content? Yes, but only in the morality dimension. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58(2), 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12346

Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., Kobrynowicz, D., & Owen, S. (2002). Perceiving discrimination against one’s gender group has different implications for well-being in women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(2), 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202282006

Schneider, D. J. (2005). The psychology of stereotyping. The Guilford Press.

Soriano, R. (2023). El número de estadounidenses residentes en México se dispara durante los últimos tres años [Number of U.S. residents in Mexico soars over the past three years]. El País. Retrieved from https://elpais.com/mexico/2023-02-08/el-numero-de-estadounidenses-residentes-en-mexico-se-dispara-durante-los-ultimos-tres-anos.html

Stephan, W. G., Boniecki, K. A., Ybarra, O., Bettencourt, A., Ervin, K. S., Jackson, L. A., McNatt, P. S., & Renfro, C. L. (2002). The Role of Threats in the Racial Attitudes of Blacks and Whites. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(9), 1242–1254. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672022812009

Stephan, W. G., & Renfro, C. L. (2002). The role of threats in intergroup relations. In D. Mackie & E. R. Smith (Eds.), Beyond prejudice: Differentiated reactions to social groups (pp. 265–283). Erlbaum.

Stephan, W. G., Ybarra, O., & Rios, K. (2015). Intergroup threat theory. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (2nd ed., pp. 255–278). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Suárez-Jaramillo, A. (2022). El caso de dos hondureños en el sur de México que huyen de las pandillas de su país [The case of two Hondurans in southern Mexico fleeing gangs in their home country]. France 24. Retrieved from https://www.france24.com/es/am%C3%A9rica-latina/20220620-migraci%C3%B3n-hondure%C3%B1os-sur-m%C3%A9xico-huyen-pandillas