Abstract

Drawing on the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory and the social capital approach, this study aims at examining a serial mediation model to explore why employees intend to leave their organization by taking into consideration psychological safety, networking ability and relational job crafting. We tested our research hypotheses with the data obtained from 218 employees working in different sectors. The results revealed that (1) psychological safety is negatively associated with intention to leave, and (2) networking ability and relational job crafting serially mediate the link between psychological safety and intention to leave. This study presents crucial evidence for organizations to retain and engage employees by justifying the importance and effects of building social relationships in the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Research on turnover indicates that voluntary turnover in organizations is more common than ever before (Huang et al., 2020). High turnover hinders the quality of human capital (Sorensen & Ladd, 2020), decreases performance (Sheehan, 2001; Rao & Argote, 2006; Watrous et al., 2006), and incurs costs such as vacancy, advertising, recruiting, orientation, training, and termination (Jones, 2004; Li & Jones, 2013; Nazir et al., 2016; Waldman et al., 2004). It seems employee turnover poses a critical threat to organizations in terms of both financial and social consequences.

Anticipating employees’ turnover behavior requires understanding the reasons for their intention to leave their workplace since, as Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) state, intentions are the predictors of actual behavior. Although, a growing body of research has been devoted to investigating the antecedents of turnover intention, such as structural, economic, social-psychological factors (Johnsrud & Rosser, 2002), as well as a lack of work-life balance (Noor, 2011), perceived organizational support (Djurkovic et al., 2008), organizational commitment (Loi et al., 2006), job satisfaction (Wang et al., 2022a, b), and social support (Mehdi et al., 2012), there is still a gap needed to be filled concerning the predictors of intention to leave. For example, while feeling safe and confident in the work environment is vitally important for employees (Newman et al., 2017), research addressing psychological safety as an antecedent of intention to leave (Chen et al., 2014; Halliday et al., 2022; Kirk-Brown & Van Dijk, 2016; Kruzich et al., 2014; Sobaih et al., 2022) is relatively scarce and requires further investigation. To address this gap, this study attempts to examine the relationship between psychological safety and intention to leave through the lenses of the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory and the social capital approach.

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory was first developed by Hobfoll (1989) to explain stress as a reaction to the environmental factors. The theory posits that stress results from a loss or a lack of valuable resources, material or non-material, that help attain goals (Hobfoll, 1989). Therefore, individuals are motivated to acquire, retain, and preserve their resources for their well-being (Hobfoll et al., 1997). Following the seminal works of Hobfoll, initial studies linked work-related resource loss and gain to psychological issues such as employee stress, burnout, and depression (Freedy & Hobfoll, 1994; Hobfoll et al., 1996, Holahan et al., 1999).

Besides its main tenet, COR theory presents eight key principles (Hobfoll et al., 1997, 2018; Hobfoll & Shirom, 2000; Hobfoll, 2011, 2012): (a) resource depletion has a greater influence on individuals than resource gain, (b) individuals should invest resources to safeguard against resource threat, cope with resource losses and acquire new resources, (c) in case of resource depletion or exhaustion, individuals tend to exhibit defensive or aggressive behavior, (d) more resources provide access to more resource, and protection against resource loss, but fewer resources lead to more resource loss and less resource acquisition, (e) when the risk of resource loss is significant, resource gain becomes more valuable, (f) resource loss affects individuals more rapidly and intensely than does resource gain, (g) resources do not function in isolation, but exist in combination, and (h) situational contexts act as a resource caravan passageways that cause loss circles or gain spirals of personal resources.

Recent studies show how lack, depletion, or the risk of resources may be related to depressive mood and anger (Hobfoll et al., 2003), satisfaction with corporate policies (Yan Mao et al., 2021), turnover intention (Lin et al., 2019), work-to-family conflict (Yang et al., 2019), negative workplace gossip (Ye et al., 2022), workplace ostracism (Xia et al., 2019), employee silence (Xu et al., 2015) and knowledge hiding (Feng & Wang, 2019). In contrast to these studies addressing the individual’s economic, personal, and psychological resources, the exploration of social capital as a relational resource within the framework of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory is relatively limited. Only a few studies grounded in COR theory have investigated the relationship between social capital and stress and turnover (Andresen et al., 2018), job performance, work engagement, and psychological well-being (Clausen et al., 2019). Given that interpersonal ties are regarded as the most powerful resource in human life (Taylor, 2020), further investigation is needed to understand the mechanisms by which social capital functions as a resource, or how it may grow exponentially with the help of other resources.

Social capital is characterized as the combination of resources offered by enduring or short-term network relationships of individuals or organizations (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Granovetter, 1983). The resources stem from connections of individuals with beneficial structural positions or personal attributes such as networking ability (Burbaugh & Kaufman, 2017; De Janasz & Forret, 2008; Lapointea & Vandenbergheb, 2018), emotional intelligent Bozionelos and Bozionelos, 2018), happiness (Oshio, 2017), and self-monitoring (Oh & Kilduff, 2008). Social capital may provide several advantages to organizations and individuals including increased organizational performance (Kidron & Vinarski-Peretz, 2022), organizational knowledge quality (Bharati et al., 2015), increased income and subjective well-being (Klein, 2013), innovative job performance (Ali-Hassan et al., 2015), and social identity (Wang et al., 2022a, b). More recent studies (Chen et al., 2021; Jo & Ellingson, 2019; Ko & Campbell, 2021) have addressed the mitigating impact of social capital on employee turnover intention, although none of them has utilized the assumptions of COR theory, nor have they investigated the related situational and individual factors, such as psychological safety, relational job crafting (RJC), and networking ability. By adopting the COR theory, it is possible to understand what these resources may facilitate the acquisition of another resource, social capital.

Despite studies on the consequences of resource loss or gain, relatively few research addresses the resource caravan passageways principle of the COR theory, which suggests the effects of contextual factors on personal resources and workplace outcomes. For example, restrictive organizational procedures and policies may act as a situational resource and lead to burnout and dissatisfaction via resource drain (Best, 2005). In another study, diversity climate impacts organizational commitment and turnover intention by promoting employees’ positive psychological capital (Newman et al., 2018). Studies also provide evidence that organizations with a health climate (Kim, 2022), organizational support (Witt & Carlson, 2006), person–environment fit (Nguyen & Borteyrou, 2016), and learning climate (Nikolova, 2016) provide conditions for the loss or gain of personal resources. Given the significance of supporting the personal resources of employees, there is a lack of research on situations, such as psychological safety in organizations, which may offer a passageway to social capital. In COR theory’s term, psychologically safer work environment may increase social capital, which may also be fostered by networking ability and RJC. Networking ability refers to the skills of forming and maintaining social interactions (Burbaugh & Kaufman, 2017), and RJC involves shaping job-based relations (Weseler & Niessen, 2016). Therefore, networking ability and RJC may act as a resource provider and increase social capital, which offers access to more other resources and protection against a possible resource loss (e.g., resources gained by the current job), resulting in what Hobfoll et al. (1997) term ‘gain spirals’.

The construct of psychological safety construct has its roots in the works of Schein and Bennis (1965) and Schein (1993), who suggested that psychological safety is crucial for people to feel safe, calm, and confident so that they can make the necessary behavioral changes to adapt. The concept was later elaborated by Edmondson (1999) and defined as a positive work climate in which employees are not hesitant to be themselves, but are authentic and willing to take risks in interpersonal relationships due to mutual trust and respect. By reducing anxiety and discouragement (Schein, 2010), and promoting learning and growing (Edmondson, 2018), psychological safety produces positive work attitudes and outcomes, such as willingness to participate in organizational activities (Kark & Carmeli, 2009), feeling more engaged at work (Edmondson, 2018), having a high level of satisfaction, and commitment (Frazier et al., 2017). According to COR theory, employees may not take a personal risk, such as leaving the organization, if they think the risk involves a loss of resources (Marx-Fleck et al., 2021). On the other hand, if they do not feel psychologically safe in the organization, they may attempt to reduce further resource loss by decreasing their commitment to the organization or seeking another job (Thanacoody et al., 2014). Moreover, from the perspective of the social capital approach, psychological safety, a situational resource (Marx-Fleck et al., 2021), may provide a relational resource, i.e., social capital. Promoting trustful and supportive social ties among employees, perception of a safe workplace climate can help them develop social capital (Baer & Frese, 2003). Thus, drawing on COR theory, we argue that psychological safety is both a resource and a resource provider that employees desire to preserve, and a resource loss due to feeling psychologically unsafe may result in turnover intention.

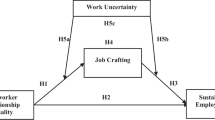

Psychological safety refers to employees’ shared belief that no one in the workplace will face negative consequences of speaking up or making mistakes (Edmondson, 2004). In a psychologically safer environment, employees may address organizational issues freely (Carmeli, 2007), ask for support or advice without fear of being judged (Carmeli et al., 2009), and appreciate each other’s work efforts (May et al., 2004). These arguments suggest that psychological safety is a significant aspect of a resourceful and healthy work environment that may increase positive outcomes and decrease negative ones. Studies indicate that psychological safety relates to organizational commitment and job satisfaction (Geisler et al., 2019; Mitterer & Mitterer, 2023; Kim, 2020), which decrease turnover intention (Suliman & Al-Junaibi, 2010; Tett & Meyer, 1993; Van Dick et al., 2004). These findings suggest that psychological safety is also negatively associated with turnover intention, which is also confirmed by the works of Chen et al. (2014), Halliday et al. (2022), Kirk-Brown and Van Dijk (2016), Kruzich et al. (2014), Sobaih et al. (2022). To extend our understanding of why psychological safety may result in decreased intention to leave, our study posits two substantial mediators: networking ability and relational job crafting (RJC). The focus is mainly on networking ability and RJC for two reasons. First, networking ability is also a facilitator that helps employees develop and enhance social capital (Burbaugh & Kaufman, 2017; De Janasz & Forret, 2008; Lapointea & Vandenbergheb, 2018). Since more networking ability means more connections, we expect that employees who are good at networking will not intend to quit their job in order to preserve their social capital as a relational resource derived from the social structure of the organization. Secondly, we argue that RJC may also be considered as another social capital facilitator. Since it involves modifying the number and extent of interactions at work, it addresses the need of employees to build connections and social relationships (Rofcanin et al., 2019; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), which, in turn, may increase their social capital. We predict that employees who relationally craft their jobs will stay in the organization because it is likely that they will maintain the good working relationships they have built according to their preferences. Therefore, integrating COR theory and the social capital approach, we argue that when employees perceive psychological safety, they will have higher networking ability and RJC, resulting in a decreased level of intention to leave. The research model is exhibited in Fig. 1.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it advances the existing research on turnover intention by investigating its relationship with a relatively overlooked concept, psychological safety, drawing on COR theory and the social capital approach. Second, the study attempts to offer a new insight into further understanding intention to leave by utilizing a social and relational perspective with a focus on networking ability and RJC. Third, the present study expands the understanding of the concept of RJC by examining networking ability as its potential antecedent, and intention to leave as its outcome. Finally, existing research has focused on the overall job crafting construct rather than investigating its individual dimensions with other organizational variables (Li et al., 2022). This study addresses this gap by providing a closer look at RJC. In sum, the study examines the association between psychological safety and intention to leave through networking ability and RJC.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

The relationship between psychological safety and intention to leave

Psychological safety entails beliefs and feelings about how other people will react if one raises questions, solicits feedback, makes comments, reports mistakes, or develops new ideas (Carmeli & Gittell, 2009; Frazier et al., 2017). Individuals who believe that the workplace is psychologically safe are more likely to seek guidance and support from their coworkers because feelings of safety allow them to reduce barriers to interactions and encourage them to make choices for personal growth (Wanless, 2016). They also tend to challenge existing organizational practices, and offer innovative solutions (Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006).

Formal and informal organizational policies and procedures that encourage comforting and supportive interactions in the workplace are considered as a psychologically safe environment in which organizational members have the chance to voice their opinions without fear of rejection, or any other negative personal consequences (Baer & Frese, 2003; Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006). Thus, psychological safety promotes a positive organizational climate by empowering employees to feel comfortable expressing their opinions and thoughts, which results in desirable work outcomes such as learning, innovation, and performance (Newman et al., 2017). Positive workplace relationships fostered by psychological safety also dissuade employees’ intention to leave the organization (Abugre, 2017; Groh, 2019; Hebles et al., 2022; Vevoda and Lastovkova, 2018) since a supportive workplace deepens an employee’s links to the organization, leading to intention to stay (Holtom & Inderrieden, 2006). Intention to leave shows the possibility of leaving the organization (Ngo-Henha, 2018).

COR theory provides a framework to explain why psychological safety may affect employees’ intention to remain in the organization. COR theory posits that individuals are driven to acquire, preserve, promote, and defend valued resources (Hobfoll, 2012), which include personal features (Hobfoll, 1989), internal resources, material resources, social support (Halbesleben et al., 2014), objectives (e.g., job), conditions (e.g., having positive social interactions or network ties with others), and energies (e.g., knowledge) (Kim et al., 2018). According to COR theory, since resource loss is harmful for individuals’ wellbeing, they tend to build additional resources to guard against any future resource loss (Hobfoll, 2011). Resource acquisition gives individuals a feeling of fulfillment (Hobfoll, 1989), and protects them against future losses while also enhancing their prestige, love, assets, or self-esteem, depending on their goals and the direction of their investment (Hobfoll, 1989). Individuals are driven to keep existing resources and acquire further resources to attain their objectives (Hobfoll, 2011; Jin et al., 2018; Lapointea & Vandenbergheb, 2018). Acquisition of resources and conservation of resources govern individuals’ behavior (Srivastava & Agarwal, 2020). When they perceive a shortage of resources or a threat of resource depletion, the drive is particularly strong (Marx-Fleck et al., 2021), causing individuals to feel stressed (Morelli & Cunningham, 2012).

Drawing on COR theory, it is highly likely that employees who consider the possibility of quitting their jobs will have to invest significant resources (cognitive, emotional, and physical) to obtain new positions in a new organization, and adjust to its social and cultural environment (Jin et al., 2018). The adaptation period to a new workplace will possibly be an exhausting journey for employees who have already invested personal resources and gained valuable resources (e.g., social support of fellow employees) in their current work (Jin et al., 2018). Therefore, having the intention to leave a psychologically safe workplace may pose a significant risk of resource loss.

In COR theory’s terms, a psychologically safe workplace, a situational resource, can also help prevent existing resource depletion (Marx-Fleck et al., 2021) since it may enable employees to gain and maintain a relational resource, i.e., social capital. From the perspective of the social capital approach, employees can accumulate resources resulting from trusting and caring social bonds among themselves, as well as a perceived safe workplace climate (Baer & Frese, 2003) Social capital refers to the advantages or resources generated via individuals’ interactions in a network (Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Lin, 1999; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998). It is embedded in social relations involving trust (Putnam, 1995), positive reputation, high standing, and personal recommendations (Baron & Markman, 2000). It facilitates access to quality, relevant, and timely information (Adler & Kwon, 2002), provides increased power and influence, legitimacy, or sponsorship within a social system (Seibert et al., 2001), enables the accomplishment of goals that would otherwise be impossible (Coleman, 1988; Kilpatrick et al., 2003). Therefore, as social capital consists of interpersonal relationships, people may suffer significant losses if those relationships are severed (Coleman, 1988) due to a turnover intention.

Relying on social capital theory’s tenets, when employees believe that their organization or work group is psychologically safe, they may freely take advantage of their positions in social networks by expressing their ideas and thoughts, and diversifying their skills and abilities, which in turn, may increase their performance. For these reasons, the intention to leave may be regarded as a loss of social capital resource accumulated through social relationships built in a safer working environment. Based on these explanations, the following hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 1

Psychological safety is negatively associated with intention to leave.

The relationship between psychological safety and networking ability

A network is a social structure formed by interactional patterns of individuals (Seibert et al., 2001). Networking ability is the capacity to form and sustain these interactions (Burbaugh & Kaufman, 2017), as well as influencing others by utilizing them in the workplace (Nesheim et al., 2017). It is a significant human talent that has the potential to enhance social capital (De Janasz & Forret, 2008). Effective networking relationships require trust (Baker, 2000), and therefore, psychological safety may be considered as a facilitator of networking ability as it cultivates a climate of trust and collaboration.

According to COR theory, people have a strong desire to acquire and preserve the resources they value most (Hobfoll, 2012; Srivastava & Agarwal, 2020). Anything that may yield a positive outcome can be considered as a value, or a resource (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Safety is one of the most motivating forms of value because it helps individuals avoid or overcome the threat of uncertainty (Schwartz, 1994). Therefore, psychological safety can be considered as a resource that people value and try to preserve.

Psychological safety is also conceived as a situational resource that helps prevent resource depletion (Marx-Fleck et al., 2021) as it may promote an environment to build social capital. According to social capital theory, social connections lead to trust in others, and more trust increases the frequency of connections (Putnam, 1995), which facilitates reciprocity and collaboration (Kilpatrick et al., 2003). When employees trust each other in a safer workplace, they tend to make more efforts in maintaining the connection, believing that the other will not take advantage of them due to the lack of opportunism (Üstüner & Iacobucci, 2012). According to the social capital theory, three types of social capital are identified in social interactions: obligations and expectations, which are based on the trusting social environment, advantages gained from the network’s information flow, and normative requirements (Coleman, 1988). For this reason, social capital is a crucial component of psychological safety since employees who have positive interpersonal interactions at work may believe that their organization is a safe environment to take initiative in relationships (Carmeli, 2007).

Relying on COR theory, psychological safety may be viewed as a resource provider that people try to preserve as it facilitates social capital development. When employees feel psychologically safe, they may increase the frequency of their connections with each other due to the increased trust, and believe it is safe to express themselves, which in turn may enhance their capacity for networking and interpersonal relationships. Based on these explanations, the following hypothesis is developed:

Hypothesis 2

Psychological safety is positively associated with networking ability.

The relationship between networking ability and relational job crafting

Job design can only be understood through the lens of employees’ social relationships and how they view and experience their jobs (Kilduff & Brass, 2010). Thus, jobs can be designed through the modification of relational boundaries in the environment (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Job crafters are able to develop a positive self-concept (Niessen et al., 2016; Rudolph et al., 2017; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001) by acting on their relational boundaries, altering the quality or quantity of contacts with their coworkers (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), and aligning their self-definitions with their jobs (Rudolph et al., 2017). Indeed, employees who design their jobs around their talents and interests consider their jobs to be more meaningful (Geldenhuys et al., 2021; Oprea et al., 2022) and feel respected and supported (Tims et al., 2015), which enables them to speak up and address issues without the fear of any risks (Carmeli et al., 2009).

Any resource, or advantage that an individual obtains due to his or her social links in a network structure is viewed as social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002; De Janasz & Forret, 2008). It allows employees to acquire and use additional resources, and influence both their own and others’ behavioral outcomes (Coleman, 1988). Social capital develops through social exchange processes and indirectly impacts resource combinations (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). As such, it may lead to the preservation of valuable resources that employees have already acquired.

Social capital development is often facilitated by networking skills (Burbaugh & Kaufman, 2017; Lapointea & Vandenbergheb, 2018). Individuals with networking ability are able to identify and cultivate a wide range of relationships and networks (Ferris et al., 2007; Munyon et al., 2015). They can readily form strong and advantageous alliances and coalitions due to their subtle nature (Ferris et al., 2007). Since social capital is acquired and becomes functional through social interactions (Kilpatrick et al., 2003), networking skills promote social capital by helping individuals reach others who can offer new information, advice, ideas, guidance, or assistance (De Janasz & Forret, 2008). Therefore, individuals with access to these assets can devise methods for obtaining further resources that are not available through formal channels (Seibert et al., 2001). With the help of networking abilities, they can use the resources when required to become influential and successful (Ferris et al., 2005, 2007).

Individuals with networking skills are selective not only in whom they include in their networks, but also in how they act in a network because they are aware of the power distribution in the organization, and others’ political behaviors and positions in the network (Blass et al., 2007). They can “read” the social context, benefit from it, and form appropriate connections to generate ideas and solutions for workplace challenges (Nesheim et al., 2017). Given that networking ability plays a significant role in the formation of proactive behaviors (Thompson, 2005) one can expect that networking ability will give rise to RJC, which is a proactive behavior. From a relational perspective, networking promotes social capital, and through social capital, employees can act on the relational boundaries of their jobs, and increase their RJC. According to COR theory, social ties are viewed as a resource that people try to preserve and defend. Through social relations and social capital, RJC will be attainable. Thus, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Networking ability is positively associated with relational job crafting.

The relationship between relational job crafting and intention to leave

Because RJC allows employees to satisfy their need to be connected and develop bonds with others (Rofcanin et al., 2019; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), it may also be regarded as a social capital provider, similar to networking ability. From the perspective of the social capital approach, employees may shape their job-related relationships to reach valuable information and feedback, and boost their belongingness by relationally crafting their jobs (Weseler & Niessen, 2016). Social capital assumes that individuals make investments in relationships with the expectation of a financial or social gain (Lin, 1999). All social relationships and structures contain some form of social capital. Individuals intentionally form and maintain relationships as long as they are beneficial (Coleman, 1988). RJC may be seen as an essential tool for developing social capital as it enables employees to form social relationships and make useful connections in the workplace. Therefore, we argue that RJC may play an important role in the development and maintenance of social capital, which may adversely affect turnover intentions.

Intention to leave includes thinking of quitting the job, planning to leave, searching for other alternative career options, and showing a willingness to change current career (Mobley et al., 1979). One of the factors effecting intention to leave is job-redesign processes (Hackman, 1980). According to the traditional job design model, managers design jobs in a top-down process (Campion & McClelland, 1993), placing employees in a passive role. In other words, managers design the jobs and tasks for all employees in a one size fits all manner (Berg et al., 2013). As it is difficult to design suitable jobs for all employees, employees are recently encouraged to participate in a job design process called job crafting (Guan & Frenkel, 2018). Thus, job crafting allows employees to create a match between their skills and job requirements (Tims & Bakker, 2010).

Through job crafting employees have the option to change their tasks and interactions to make the jobs and work environment more meaningful (Slemp & Vella- Brodrick, 2013). Job crafting has three dimensions. Task crafting refers to a change in tasks in terms of quantity, complexity, and method, whereas cognitive crafting is related to a change in cognitive task boundaries (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). On the other hand, RJC involves rearranging the number and quality of job-related relationships (Weseler & Niessen, 2016). Recently, the social aspect of the job has gained increased importance (Rofcanin et al., 2019) due to its effects on employee behavior (Grant & Parker, 2009). Social aspect of the job includes interactions and relationships between employees and affects the way of doing the job (Kilduff & Brass, 2010). Employees expanding their job-based relationships can improve their work performance by accessing work-related resources (Kilduff & Brass, 2010), creating a supportive and collaborative work environment (Rofcanin et al., 2019). This recent emphasis on the social aspect of the job underscores the importance of RJC, a possible factor that may influence intention to leave.

From the perspective of COR theory, as relationships between employees are seen as a resource; RJC may be regarded as a job resource because it allows employees to form job-based relationships. Job resources provide access to work-related resources and opportunities for personal growth and skill development (Ingusci et al., 2016). Given that when individuals lose the resources that they care about, they feel stress (Zhang et al., 2019), lack of RJC may cause negative consequences in the organization such as intention to leave. Drawing upon COR theory, job crafting may be considered as a strategy to maintain resources (Zhang et al., 2019) as well as to acquire new resources, which increases the possibility of employee retention. Consistent with this line of thinking, job crafting can be regarded as a process in which employees strive to maximize job resources (Slemp & Vella-Brodrick, 2013). The social capital approach proposes that when employees foster and expand their relationships within their job context, they gain access to critical information, receive feedback from their peers, and improve the quantity and quality of social interactions, which in turn may contribute to an enhanced sense of belongingness and intention to stay (Weseler & Niessen, 2016). By crafting job-based relationships, employees can acquire more work-related resources (Kilduff & Brass, 2010), which strengthens positive organizational outcomes in the organization (Volmer & Wolff, 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). This in turn decreases the likelihood of intention to leave. In line with these assumptions, the below hypothesis is developed.

Hypothesis 4

Relational job crafting is negatively associated with intention to leave.

Psychological safety, networking ability, relational job crafting, and intention to leave

COR theory posits that individuals must acquire and accompany necessary resources to abstain from resource loss or resource depletion (Hobfoll, 2011). Psychological safety may play a pivotal role in avoiding these losses in the workplace. As an organizational resource, psychological safety helps protect against the loss and depletion of resources because it creates comfort that allows employees to express themselves freely and perceive fewer risks within the workplace (Wang et al., 2022a, b). In addition, from the perspective of social capital theory, psychological safety is considered a major provider of social capital since it fosters and encourages trustful and supportive social ties in the workplace (Baer & Frese, 2003). Psychological safety enhances the relationship quality between employees since individuals who are psychologically safe at work feel free to voice their opinions and talk about their mistakes without hesitation (Edmondson, 1999). Therefore, in a psychologically safe environment, employees may feel more connected and supported, and be motivated to strengthen social bonds and increase social capital.

Specifically, we expect that psychological safety may affect networking ability and RJC serially. Considering networking ability as a crucial facilitator of social capital development (Lapointea & Vandenbergheb, 2018), RJC as a social capital provider, employees who feel psychologically safer may have more social capital and high-quality relationships in the workplace via networking ability and RJC, which in turn may negatively affect their intention to leave the organization.

Based on the theoretical explanations, we predict that (1) psychological safety may decrease intention to leave as psychological safety is defined as an organizational resource that eliminates the loss or depletion of resources; and (2) networking ability and RJC serially mediate the relationship between psychological safety and intention to leave. Taking together, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 5

Networking ability and relational job crafting serially mediate the relationship between psychological safety and intention to leave.

Methodology

Participants

The sample of this study comprised 218 participants working in different sectors such as education, banking, and health care in Turkey in 2021. The questionnaire, which was sent electronically to 436 participants, was filled out by 218 people, thus yielding a 50% response rate. An electronic questionnaire including the items of intention to leave, networking ability, psychological safety, RJC, and demographic questions such as gender, age, education, organizational tenure, and sectoral background was distributed. The participants consisted of 40.8% (n = 89) female and 59.2% (n = 129) male. The average age was 40.23 years (SD = 8.23), and the average organizational tenure was 15.13 years (SD = 8.75). The results of the demographics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Instruments

For the measurement of the constructs, we utilized four established scales, as outlined in the Appendix. First, while researchers have created various instrument tools to assess employees’ intention to leave, such as those developed by Mobley et al. (1978), Cammann et al. (1979), Singh (2000), and Firth et al. (2004), we chose a combined scale approach based on previous studies. This approach involved incorporating items from the scales developed by Landau and Hammer (1986) and Nadler et al. (1975) to ensure a comprehensive measurement of the intention to leave construct. This decision was influenced by previous research conducted by Wayne et al. (1997) and Conley and You (2014), who utilized a similar approach to enhance the comprehensiveness of measuring intention to leave. Moreover, Landau and Hammer’ scale (1986) is widely recognized as one of the most commonly employed measures for assessing intention to leave (Cooper-Hakim & Viswesvaran, 2005). Numerous studies have validated the reliability and validity of this instrument, further supporting its credibility and robustness in measuring intention to leave. Additionally, the convenience of the scale to Turkish culture has been verified by a previous study conducted in Türkiye (Bozkurt & Demirel, 2019). The study reported that the combined scale consisting of three items from Landau and Hammer’s (1986) scale and one item from Nadler et al.’s (1975) scale demonstrated high validity and reliability. Based on these findings, we opted for the combined version of the Intention to Leave Scale, considering its strong psychometric properties and its alignment with the cultural context of Türkiye. In the Turkish version of the scale, we utilized the items as translated in the study by Bozkurt and Demirel (2019). An example item was “I often think about quitting”. Item responses were obtained on a 5-point Likert scale and responses ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). High scores showed higher levels of intention to leave. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was computed as 0.94.

Regarding the measurement of psychological safety, several valid scales have been developed by Anderson and West (1998), May et al. (2004), and Tucker (2007). However, a significant number of studies have utilized Edmondson’s (1999) Psychological Safety Scale (Frazier et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2017; Edmondson & Bransby, 2023), given its widespread use. Additionally, the scale has been validated in numerous studies conducted within the Turkish culture, as evidenced by research conducted by Yener (2015) and Uğurlu and Ayas (2016). Thus, we opted to employ Edmondson’s Psychological Safety Scale, considering its established validity and its relevance to the Turkish context. The scale consisted of items such as “No one in this organization would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts”. The extent to which participants agreed to items on the scale was asked on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). The scale reliability (coefficient alpha) was 0.89.

Third, as Bendella and Wolff (2020) stated, there are two commonly employed instruments in networking research to measure an individual’s networking ability: The Political Skill Inventory Scale developed by Ferris et al. (2005) and Networking Behavior Scale developed by Wolff and Moser (2006). Although Wolff and Moser’s (2006) scale is the most comprehensive construct containing 44 items with six subscales to measure networking (Wolff & Spurk, 2019), it did not correspond with our survey design due to its length. Given that we already had three other instruments and considering the potential burden of a lengthy scale on our respondents, we decided to prioritize the use of the Political Skill Inventory Scale developed by Ferris et al. (2005). The Political Skill Inventory Scale, which includes a subdimension specifically measuring networking ability, offers a concise and high-quality assessment with six items. Furthermore, the Turkish version of the scale has been validated for its reliability and validity in previous studies, as demonstrated by the research conducted by Ozdemir and Goren (2015). An example item was “I spend a lot of time at work developing connections with others”. The responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The internal reliability of the scale was found 0.84.

Lastly, relational job crafting was assessed by utilizing the Job Crafting Questionnaire developed by Slemp and Vella-Brodrick (2013), despite the existence of alternative scales created by Leana et al. (2009), Laurence (2010), Niessen et al. (2016), and Bizzi (2017). We chose Slemp and Vella-Brodrick’s (2013) scale because it has been extensively validated for its strong construct validity and reliability across diverse cultural contexts, including Turkish, as demonstrated in studies conducted by Slemp et al. (2021) and Kerse (2017). Formed by following Wrzesniewski and Dutton’s (2001) framework, the Job Crafting Questionnaire consists of cognitive, task and relational crafting subdimensions, comprising a total of 19 items. To evaluate the crafting activities regarding the interpersonal relationships of respondents, we specifically utilized the relational crafting subdimension with seven items, aligning it with our research objectives. The scale was translated into Turkish by Kerse (2017). A sample item was “Engage in networking activities to establish more relationships”. The extent to which participants agreed to items on the scale was asked on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). The reliability of the scale measured by Cronbach’s alpha was found 0.86.

Data analysis

To test our hypotheses regarding the serial mediation role of networking ability and RJC in the relationship between psychological safety and intention to leave, we employed SPSS Process 3.4. (Model 6) by applying the bootstrapping method (Hayes, 2013). We tested the indirect effects of serial mediators via a nonparametric bootstrap approach using 5,000 random samples with a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval. The process of nonparametric resampling in testing mediation, as described by Preacher and Hayes in 2008, avoids the need to assume normality of the sampling distribution. This approach remedies the power problem introduced by asymmetries and other forms of nonnormality (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Moreover, compared with the four-step multiple regression approach proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986), this approach is viewed as a more powerful method (Blanco-Donoso et al., 2017). Thus, this approach is highly recommended for effect-size estimation and hypothesis testing in mediation analyses (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Accordingly, a nonparametric bootstrapping approach was adopted in the data analytics procedure.

Results

Common method bias test

We gathered the data from the same participants with a self-reporting survey. Self-reporting measures may cause social desirability in selecting scale items (Kline et al., 2000) and social desirability may be a source of common method variance (Kline et al., 2000). As the data for dependent and independent variables were collected using a single online survey, we first conducted a common method bias test. Common method bias can be regarded as a third variable in predicting the relationship between two variables as it may have the potential to inflate or deflate the observed relationships between variables (Jakobsen & Jensen, 2015). To understand the potential impacts of common method bias on the results of the study, many statistical analyses were carried out. We first examined a correlation matrix of the measured variables. The value of correlation above 0.90 is an indicator of common method bias existence. As the highest value of correlation among measured variables is 0.625, the correlation among the variables does not entail a common method bias problem (see Table 2). Then, we employed Harman’s single factor test (Podsakoff et al., 2003), in which all variables are inserted into an exploratory factor analysis to identify whether they load on a single factor, or one factor explains the majority of the covariance of variables (Friedrich et al., 2009). The results revealed 4 components with an eigen value greater than one. The first factor explained 39.3% of the variance and 4 factors explained 65.95% of the variance together. As the result (39.3%) was lower than the accepted threshold of 50%, it did not account for the majority of the variance. Next, following the suggestions of Podsakoff et al. (2003), the common latent factor (CLF) was tested to determine the common method bias using AMOS. Firstly, we inserted a common latent factor (CLF) into the structural model. We compared the standardized regression weights for all items in the model with and without CLF. As the differences between standardized regression weights were less than the threshold value of 0.2 (Serrano Archimi et al., 2018), we concluded that there was no common method bias problem in the study.

Reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity

We checked the reliability to examine the consistency of instruments in the measurement model. The reliability of the construct is carried out by measuring composite reliability and Cronbach alpha. The threshold value of composite reliability (CR) or Cronbach alpha is 0.70 (Hair et al., 1998; Cronbach, 1951). The CR values ranging from 0.56 to 0.89 and Cronbach alpha values ranging from 0.83 to 0.93 met the requirements for the reliability of the measurement (see Table 3).

The construct validity was examined using convergent validity and discriminant validity tests. To establish convergent validity, we measured factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE). The threshold values for factor loadings for both CR and AVE values were 0.50. Factor loadings fell in the range of 0.60 to 0.93 and AVE values fell in the range of 0.56 to 0.84. The results of factor loadings, and AVE values were above the acceptable level indicating that convergent validity was supported (see Table 3).

The discriminant validity was measured by comparing the square root of AVE with the correlation coefficients between variables. Discriminant validity shows whether each construct is differentiated from the other (Chou et al., 2013). The square root of AVE of all constructs, which was significantly higher than its correlation coefficients with other factors, showed good discriminant validity. As seen in Table 2, the AVE values of each construct were greater than the correlation coefficients. Therefore, discriminant validity was achieved.

We then conducted a confirmatory factor analysis applying the maximum likelihood parameter estimation method via AMOS to examine how the data fit the model. For this purpose, we checked the indices of the relative chi-square (χ2/df), goodness of fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square of error approximation (RMSEA). The results revealed that all the actual indices had better values than the cut-off values recommended by Hu and Bentler (1999) and Browne and Cudeck (1993). Put differently, all scales had a good and acceptable fit. Confirmatory factor analysis results are presented in Table 4.

Before testing the hypotheses of the model, we measured the tolerance value and variance inflation factor (VIF) to check the multicollinearity among independent variables. Tolerance values more than 0.01 or VIF values less than 10 are accepted threshold levels for multicollinearity (Pambreni et al., 2019). The tolerance value and VIF scores in the present study indicated all variables were free of multicollinearity (see Table 5). A rule of thumb for regression analysis is that there should be no autocorrelation among the measured variables. Durbin-Watson statistics test was conducted to check the autocorrelation for each independent construct. The values between 0 and 4 show that there is no autocorrelation. The result of Durbin Watson statistics (1.86) indicated that autocorrelation was not detected in the study (see Table 5).

Descriptive statistics

Means, standard deviations, reliability coefficients and correlations among measured variables are shown in Table 6. Correlation results revealed a significant negative correlation between intention to leave and psychological safety (r= -0.45; p < 0.01), networking ability (r= -0.19; p < 0.01), and RJC (r= -0.34; p < 0.01). Furthermore, psychological safety had a significant positive correlation with networking ability (r = 0.51; p < 0.01), and RJC (r = 0.58; p < 0.01). Networking ability had a significant positive correlation with RJC (r = 0.62; p < 0.01). Respondents had a high level of psychological safety (Mean = 3.56), networking ability (Mean = 3.61), and RJC (Mean = 3.81).

Hypotheses testing

To test the hypotheses of the study, we carried out a serial mediation analysis with bootstrap techniques to analyze the serial mediation effect of networking ability and RJC in between psychological safety and intention to leave (Hayes, 2013). For this purpose, we checked the resulting output, including point estimates, standard error, bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (CI) for indirect effects, and unstandardized path coefficients for all paths in the mediation model. To assess the significance of the indirect effects, bias-corrected 95% CI is used as an indicator. If CI’s upper and lower bounds do not contain zero, it indicates that the mediation effect is statistically significant (Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008).

As the first step to mediation analysis, we tested the relationship between psychological safety and intention to leave. The results showed that psychological safety significantly and negatively affected intention to leave (β= -0.52, SE = 0.09, p < 0.01), which suggests that there is less intention of employees to quit the psychologically safe organization. Hence, Hypothesis 1 was supported. The second hypothesis predicted that psychological safety was positively related to networking ability. The findings showed that psychological safety had a positive relationship with networking ability (β = 0.46, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01), which supported Hypothesis 2. The third hypothesis suggested that individuals having networking ability could craft their job-based relationships in the organization. In line with this assumption, we found that there was a positive relationship between networking ability and relational job crafting (β = 0.42, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01). Hence, Hypothesis 3 was supported. The prediction of Hypothesis 4 was that RJC is negatively associated with intention to leave. Crafting job-based relationships may decrease the intention of employees to quit the organization. The results of this study revealed a negative relationship between them (β= -0.28, SE = 0.12, p < 0.01). Thus, Hypothesis 4 was supported. Finally, the fifth hypothesis predicted that networking ability and RJC serially mediated the relationship between psychological safety and intention to leave. The indirect impact of psychological safety on intention to leave via negative serial mediation of networking ability and RJC was significant (β= -0.57, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01). Based on the recommendations regarding mediation analysis proposed by Preacher and Hayes (2004, 2008), it was concluded that the serial mediation effect was significant since bias-corrected 95% CI excluded zero (CI= -0.13, -0.01). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 received support. Table 7 indicates the direct and indirect effects of psychological safety on the intention to leave via the mediation effects of networking ability and RJC.

Discussion

Key findings

This study sheds new light on the link between psychological safety and employees’ intention to leave by identifying the roles of networking ability and RJC as two key mediators in this relationship. Drawing on COR theory and social capital theory, the study theorizes and tests a serial mediation model to elucidate whether social relationship-based resources generated by a psychologically safe work environment influence the employees’ turnover intention.

Consistent with our first hypothesis, the results demonstrate that psychological safety is negatively associated with intention to leave, which supports previous studies (Abugre, 2017; Groh, 2019; Hebles et al., 2022; Vevoda & Lastovkova, 2018), and provides additional evidence for the crucial, yet mostly ignored the effect of psychological safety on intention to leave.

Secondly, to our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate the positive link between psychological safety and networking ability. Although there is no empirical research exploring the association to compare to our results, the finding is consistent with Ferris et al.’s (2007) argument that the sense of personal security is likely related to greater control over the work environment. These scholars also emphasize that individuals with high networking ability believe they can control their social environment by expressing high self-confidence, which suggests that a high level of psychological safety correlates with better networking abilities since it provides comfort and confidence in interpersonal relationships, which is supported in our study.

Thirdly, our findings indicate that networking ability is positively associated with RJC, which appears to be the first to explore the association. Despite the lack of empirical evidence that supports our results, they are congruent with the theoretical assumptions in the existing literature. For instance, Nesheim et al. (2017) state that individuals with high networking ability are able to ‘read’ contextual clues and establish beneficial relationships accordingly. In addition, Ferris et al. (2007) posit that networking ability makes it easier to build social capital and use it when required. Thus, individuals with networking ability not only know whom to connect with, but also know how they can benefit from this connection. Our findings provide empirical evidence for these theoretical assumptions. With a high networking ability, it is much easier for employees to shape and change the boundaries of their social relationships in terms of RJC.

Fourth, our findings illustrate that RJC is negatively associated with the intention to leave. Although no study is found to examine the direct relationship between RJC and intention to leave, our results corroborate the studies which investigated the link between overall job crafting construct and intention to leave (Oprea et al., 2022; Xin et al., 2021). Our study presents empirical evidence that RJC may be a factor for employees not to leave their organization. Since relational job crafters build their work relationships according to their own preferences, they may desire to preserve these relationships by staying in the organization.

Lastly, our results show that psychological safety influences intention to leave via networking ability and RJC. In line with the theories of COR and social capital, psychological safety results in high networking ability and RJC, which in turn reduces the intention to leave the organization.

Theoretical implications

This study adds to the growing body of research in many ways. First, by empirically unraveling an important negative association between psychological safety and intention to leave, the present study advances the existing literature. The findings also contribute to the tenets of COR theory by confirming that psychological safety plays a vital role as an organizational resource and social capital provider that lowers turnover intention since it protects employees against resource loss or depletion.

Second, since there are inconsistent and unexpected findings in turnover literature regarding the effects of social relations on intention to leave (Jo & Ellingson, 2019), the present study expands the understanding of how social relationships affect intention to leave by introducing two vital factors, networking ability and RJC. Drawing on COR theory, our study shows networking ability and RJC play crucial roles in preserving valuable resources as they configure social relationships at work. Moreover, our study integrates COR theory and the social capital approach, arguing that via networking ability and RJC, employees can expand their social capital and access more resources that provide them to have more social bonds and high-quality relationships.

Third, our study extends research on intention to leave by exploring the effects of networking ability and RJC. Although the previous studies examined the impacts of overall political skill and job crafting on intention to leave (García-Chas et al., 2019; Oprea et al., 2022), our investigation suggests a relation-focused model by specifically exploring the role of networking ability and RJC. Thus, the current study provides a deeper insight into the concept of intention to leave by conforming that obtaining relationship-based resources and social capital via networking ability and RJC is influential in the decision to stay or leave the organization.

Fourth, we actively respond to recent calls for further discovery of the antecedents and outcomes of RJC (Li et al., 2022; Rofcanin et al., 2019). Although RJC has mostly been investigated as a sub-dimension of job crafting construct for the past 20 years (Li et al., 2022), research examining RJC as an individual variable is very scant, and requires deeper exploration. To fill this gap, we identify networking ability as an antecedent and intention to leave as an outcome of RJC in the present study.

Finally, to the best of our knowledge, existing studies have not yet studied intention to leave by using a comprehensive model including psychological safety, networking ability and RJC. By doing so, this study adds to the rapidly expanding field of turnover literature by introducing new antecedents.

Practical implications

Our study yields managerial implications to reduce and eliminate employees’ intention to leave the organization. First, companies should promote not only physical safety, but also psychological safety, by for example introducing training programs to encourage a psychologically safe workplace. In a psychologically safe environment, employees feel free to share their work-related ideas without hesitation, which may stimulate initiation and innovation in the organization. Managers should promote values that strengthen social bonds and facilitate cooperation among employees through socialization. Second, since network position matters (Jo & Ellingson, 2019), managers should consider the connections shaping networks, which helps them eliminate turnover intention. It is harder to leave for the employees who are connected to others that provide valuable resources (Jo & Ellingson, 2019). Accordingly, managers should support employees to strengthen positive social relationships to retain them.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Our study has several limitations. First, although we tested the common method bias and indicated that it was not a major problem, the current study may have social desirability bias due to the use of a self-reporting questionnaire. Therefore, further studies can test our research model with a longitudinal research design to obtain more accurate results. Second, the sample size of this research limits the generalization of the results. It is suggested that future research test our model with a larger sample from different industries to reach conclusive results. Moreover, our study does not include the effect of the supervisors in the model. Future research can also investigate the role of supervisor support, trust in the supervisor, and leader-member exchange to shed light on the relational nature of turnover intention.

Appendix: Questionnaire items

Items on the Intention to Leave Scale.

-

1.

As soon as I can find a better job, I’ll leave ________.

-

2.

I am seriously thinking about quitting my job.

-

3.

I am actively looking for a job outside ________.

-

4.

I often think about quitting.

Items on the Psychological Safety Scale.

-

1.

If you make a mistake in this organization, it is often held against you.

-

2.

Employees of this organization are able to bring up problems and tough issues.

-

3.

People in this organization sometimes reject others for being different.

-

4.

It is safe to take a risk in this organization.

-

5.

It is difficult to ask other employees of this organization for help.

-

6.

No one in this organization would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts.

-

7.

Working with employees of this organization, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized.

Items on the Networking Ability Scale.

-

1.

I spend a lot of time and effort at work networking with others.

-

2.

I am good at building relationships with influential people at work.

-

3.

I have developed a large network of colleagues and associates at work whom I can call on for support when I really need to get things done.

-

4.

At work, I know a lot of important people and am well connected.

-

5.

I spend a lot of time at work developing connections with others.

-

6.

I am good at using my connections and network to make things happen at work.

Items on the Relational Job Crafting Scale.

-

1.

I engage in networking activities to establish more relationships.

-

2.

I make an effort to get to know people well at work.

-

3.

I organize or attend work related social functions.

-

4.

I organize special events in the workplace (e.g., celebrating a co-worker’s birthday).

-

5.

I introduce myself to co-workers, customers, or clients I have not met.

-

6.

I choose to mentor new employees (officially or unofficially).

-

7.

I make friends with people at work who have similar skills or interests.

References

Abugre, J. B. (2017). Relations at workplace, cynicism and intention to leave: a proposed conceptual framework for organizations. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(2), 198–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-09-2016-1068

Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2002.5922314

Ali-Hassan, H., Nevo, D., & Wade, M. (2015). Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: The role of social capital. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 24(2), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2015.03.001

Anderson, N. R., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(3), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199805)19:3<235::AID-JOB837>3.0.CO;2-C

Andresen, M., Goldmann, P., & Volodina, A. (2018). Do overwhelmed expatriates intend to leave? The effects of sensory processing sensitivity, stress, and social capital on expatriates’ turnover intention. European Management Review, 15(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12120

Baer, M., & Frese, M. (2003). Innovation is not enough: Cimates for initiative and psychological safety, process innovations, and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.179

Baker, W. (2000). Achieving success through social capital: Tapping the hidden resources in your personal and business networks. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2001.5229708

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Baron, R. A., & Markman, G. D. (2000). Beyond social capital: How social skills can enhance entrepreneurs’ success. Academy of Management Executive, 14(1), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2000.2909843

Bendella, H., & Wolff, H. G. (2020). Who networks? –A meta-analysis of networking and personality. Career Development International, 25(5), 461–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072719844924

Berg, J. M., Dutton, J. E., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2013). Job crafting and meaningful work. In B. J. Dik, Z. S. Byrne, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Purpose and meaning in the workplace (pp. 81–104). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14183-005

Best, R. G., Stapleton, L. M., & Downey, R. G. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job burnout: The test of alternative models. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 10(4), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.441

Bharati, P., Zhang, W., & Chaudhury, A. (2015). Better knowledge with social media? Exploring the roles of social capital and organizational knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 19(3), 456–475. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-11-2014-0467

Bizzi, L. (2017). Network characteristics: When an individual’s job crafting depends on the jobs of others. Human Relations, 70(4), 436–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716658963

Blass, F. R., Brouer, R. L., Perrew?, P. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2007). Politics understanding and networking ability as a function of mentoring: The roles of gender and race. J Leadersh Organ Stud, 14(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071791907308054

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood Press.

Bozionelos, G., & Bozionelos, N. (2018). Trait emotional intelligence and social capital: The emotionally unintelligent may occasionally be better off. Personality and Individual Differences, 134, 348–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.037

Bozkurt, H. O., & Demirel, Z. (2019). Job security as the predictor of turnover intention in hotel businesses: Mediator role of job embeddedness. Business & Management Studies: An International Journal, 7(4), 1383–1404. https://doi.org/10.15295/bmij.v7i4.1184

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Burbaugh, B., & Kaufman, E. K. (2017). An examination of the relationships between leadership development approaches, networking ability, and social capital outcomes. The Journal of Leadership Education, 16(4), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.12806/V16/I4/R2

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan organisational assessment questionnaire. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Unpublished Manuscript, University of Michigan.

Campion, M. A., & McClelland, C. L. (1993). Follow-up and extension of the interdisciplinary costs and benefits of enlarged jobs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(3), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.3.339

Carmeli, A. (2007). Social capital, psychological safety and learning behaviors from failure in organizations. Long Range Planning, 40(1), 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2006.12.002

Carmeli, A., & Gittell, J. H. (2009). High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(6), 709–729. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.565

Carmeli, A., Brueller, D., & Dutton, J. E. (2009). Learning behaviors in the workplace: The role of high-quality interpersonal relationships and psychological safety. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 26(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.932

Chen, C., Liao, J., & Wen, P. (2014). Why does formal mentoring matter? The mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of power distance orientation in the chinese context. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(8), 1112–1130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.816861

Chen, X., Peng, J., Lei,X., et al. (2021). Leave or stay with a lonely leader? An investigation into whether, why, and when leader workplace loneliness increases team turnover intentions. Asian Business Management, 20, 280–303. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-019-00082-2

Chou, T. Y., Chou, S. C. T., Jiang, J. J., & Klein, G. (2013). The organizational citizenship behavior of IS personnel: Does organizational justice matter? Information and Management, 50(2–3), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.02.002

Clausen, T., Meng, A., & Borg, V. (2019). Does social capital in the workplace predict job performance, work engagement, and psychological well-being? A prospective analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 6110, 800–805. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001672

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780243

Conley, S., & You, S. (2014). Role stress revisited: Job structuring antecedents, work outcomes, and moderating effects of locus of control. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 42(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143213499264

Cooper-Hakim, A., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). The construct of work commitment: Testing an integrative framework. Psychological Bulletin, 131(2), 241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.241

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

De Janasz, S. C., & Forret, M. L. (2008). Learning the art of networking: A critical skill for enhancing social capital and career success. Journal of Management Education, 32(5), 629–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1052562907307637

Djurkovic, N., McCormack, D., & Casimir, G. (2008). Workplace bullying and intention to leave: The moderating effect of perceived organizational support. Human Resource Management Journal, 18(4), 405–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2008.00081.x

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2F2666999

Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. In R. M. Kramer, & K. S. Cook (Eds.), Trust and distrust in organizations: Dilemmas and approaches (pp. 239–272). Russell Sage Foundation.

Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. John Wiley & Sons.

Edmondson, A. C., & Bransby, D. P. (2023). Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10, 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-055217

Feng, J., & Wang, C. (2019). Does abusive supervision always promote employees to hide knowledge? From both reactance and COR perspectives. Journal of Knowledge Management, 23(7), 1455–1474. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2018-0737

Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Kolodinsky, R. W., Hochwarter, W. A., Kacmar, C. J., Douglas, C., & Frink, D. D. (2005). Development and validation of the political skill inventory. Journal of Management, 31(1), 126–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0149206304271386

Ferris, G. R., Treadway, D. C., Perrewé, P. L., Brouer, R. L., Douglas, C., & Lux, S. (2007). Political skill in organizations. Journal of Management, 33(3), 290–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0149206307300813

Firth, L., Mellor, D. J., Moore, K. A., & Loquet, C. (2004). How can managers reduce employee intention to quit? Journal of Managerial Psychology, 19(2), 170–187. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410526127

Fishbein, M. A., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. MA: Addison Wesley. https://philarchive.org/archive/FISBAI

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12183

Freedy, J. R., & Hobfoll, S. E. (1994). Stress inoculation for reduction of burnout: A conservation of resources approach. Anxiety Stress Coping, 6(4), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615809408248805

Friedrich, T. L., Byrne, C. L., & Mumford, M. D. (2009). Methodological and theoretical considerations in survey research. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.01.001

García-Chas, R., Neira-Fontela, E., Varela-Neira, C., & Curto-Rodríguez, E. (2019). The Effect of Political Skill on Work Role Performance and Intention to Leave: A Moderated Mediation Model. J Leadersh Organ Stud, 26(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818774547

Geisler, M., Berthelsen, H., & Muhonen, T. (2019). Retaining social workers: The role of quality of work and psychosocial safety climate for work engagement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Human Service Organizations: Management Leadership & Governance, 43(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2019.1569574

Geldenhuys, M., Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2021). How task, relational and cognitive crafting relate to job performance: A weekly diary study on the role of meaningfulness. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 30(1), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1825378

Granovetter, M. (1983). The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory, 1, 201–233.

Grant, A. M., & Parker, S. K. (2009). Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 317–375. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903047327

Groh, E. (2019). Psychological safety as a potential predictor of turnover intention. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Lund University, Sweden.

Guan, X., & Frenkel, S. (2018). How HR practice, work engagement and job crafting influence employee performance. Chinese Management Studies, 12(3), 591–607. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-11-2017-0328

Hackman, J. R. (1980). Work redesign and motivation. Professional Psychology, 11(3), 445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.11.3.445

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0149206314527130

Halliday, C. S., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., Stride, C., & Zhang, H. (2022). Retaining women in male-dominated occupations across cultures: The role of supervisor support and psychological safety. Human Performance, 35(3–4), 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2022.2050234

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24018134

Hebles, M., Trincado-Munoz, F., & Ortega, K. (2022). Stress and turnover intentions within healthcare teams: The mediating role of psychological safety, and the moderating effect of COVID-19 worry and supervisor support. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.758438

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources, a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resource caravans and engaged settings. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(1), 116–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02016.x

Hobfoll, S. E. (2012). Conservation of resources and disaster in cultural context: The caravans and passageways for resources. Psychiatry, 75(3), 227–232. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.3.227

Hobfoll, S. E., & Shirom, A. (2000). Conservation of resources theory: Applications to stress and management in the workplace. In R. T. Golembiewski (Ed.), Handbook of organizational behavior (pp. 57–80). Newyork, London: Taylor & Francis Group.

Hobfoll, S. E., Freedy, J. R., Green, B. L., & Solomon, S. D. (1996). Coping in reaction to extreme stress: The roles of resource loss and resource availability. In M. Zeidner, & N. S. Endler (Eds.), Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications (pp. 322–349). John Wiley & Sons.

Hobfoll, S. E., Dunahoo, C. A., & Monnier, J. (1997). Conservation of resources and traumatic stress. In J. R. Freedy, & S. E. Hobfoll (Eds.), Traumatic stress: From theory to practice (pp. 29–47). New York: Springer Science + Business Media.

Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.3.632

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Holahan, C. J., Moos, R. H., Holahan, C. K., & Cronkite, R. C. (1999). Resource loss, resource gain, and depressive symptoms: A 10-year model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(3), 620–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.3.620

Holtom, B. C., & Inderrieden, E. J. (2006). Integrating the unfolding model and job embeddedness model to better understand voluntary turnover. Journal of Managerial Issues, 18(4), 435–452. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40604552

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huang, W., Wang, D., Pi, X., & Hewlin, P. F. (2020). Does coworkers’ upward mobility affect employees’ turnover intention? The roles of perceived employability and prior job similarity. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1861058

Ingusci, E., Callea, A., Chirumbolo, A., & Urbini, F. (2016). Job crafting and job satisfaction in a sample of italian teachers: The mediating role of Perceived Organizational support. Electronic Journal of Applied Statistical Analysis, 9(4), 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1285/i20705948v9n4p675

Jakobsen, M., & Jensen, R. (2015). Common method bias in public management studies. International Public Management Journal, 18(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.997906

Jin, M. H., McDonald, B., & Park, J. (2018). Person–organization fit and turnover intention: Exploring the mediating role of employee followership and job satisfaction through conservation of resources theory. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 38(2), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0734371X16658334.

Jo, J., & Ellingson, J. E. (2019). Social relationships and turnover: A multidisciplinary review and integration. Group & Organization Management, 44(2), 247–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601119834407