Abstract

The purpose of the present study was to investigate the stress—burnout link in entrepreneurship by employing the role stress theory’s tri-component conceptualization (i.e., role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload) using a novel statistical method entitled, Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA). The NCA is based on necessity logic, in contrast to variance-based methodologies (e.g., regression analysis and structural equation modeling) based on sufficiency logic, which seeks to assess whether an increase in the predictor variable is associated with an increase in the outcome variable. NCA aims to determine if there is a critical (necessary) determinant for an event to occur. In other words, NCA helps to answer questions, which allows identification of the necessity in type and the degree of concern for necessity linkages. Data were collected from self-identified American entrepreneurs (N = 285). The NCA's results were consistent with the conclusion of several variance-based research that identified the overall role of stress as a prerequisite for burnout. However, the three components of entrepreneurial role stress were not the necessary conditions for the development of entrepreneurial burnout. The present study is the first to use the NCA to investigate the role stress-burnout link in entrepreneurship, which has important theoretical and methodological implications. Theoretically, future studies should frame the necessary for developing entrepreneurial role stress in a broader manner, going beyond the tri-component conceptualization of role stress. And, methodologically, sufficiency logic analyses should be accompanied and supported by necessary logic analyses to deepen our understanding regarding various aspects of entrepreneurs’ well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurs are a vital part of society and are frequently referred to as cultural and economic heroes (Anderson & Warren, 2011; Cunningham & Fraser, 2022; Kalden et al., 2017). Entrepreneurship is one of the most challenging professions (Jennings & Brush, 2013; Montanari et al., 2021). Likewise, it has been expressed that “entrepreneurship is not a career where everything goes smoothly and without difficulties” (Sheehan & St-Jean, 2014, p. 2). For instance, it is widely acknowledged that entrepreneurship is one of the most stressful jobs (Stephan, 2018), which can entail a poor work-life balance (Adisa et al., 2019), long working hours (Forson, 2013), and health issues (Stephan, 2018). Several academics (e.g., Fernet et al., 2016; Nambisan & Baron, 2021; Palmer et al., 2021) have noted that entrepreneurship-related personal costs can also have consequences at firm and societal levels.

It is estimated that there are over 582 million entrepreneurs globally (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2018). Additionally, many individuals identified as entrepreneurs have established ventures in recent years (Adisa et al., 2019). Given the importance of entrepreneurship, several academics have focused on researching entrepreneur well-being (e.g., Amorós et al., 2021; Wiklund et al., 2018, 2019). Consistently, some academics have examined entrepreneur well-being-related topics, such as entrepreneurial stress (e.g., Baron et al., 2016; Cardon & Patel, 2015; Lerman et al., 2021), entrepreneurial burnout (e.g., Li et al., 2021; Manzano-García et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2015), entrepreneurial psychological well-being (e.g., Guberina & Wang, 2021; Lanivich et al., 2021; Shir et al., 2019), and entrepreneurial eudaimonic well-being (Nikolaev et al., 2022) to list a few. However, it has been emphasized that further research into the well-being of entrepreneurs is warranted (e.g., Wiklund et al., 2019).

One such concept related to entrepreneurial well-being is the link between stress and its associated outcomes (e.g., burnout; Das, 2011; Quiun et al., 2022; Torrès et al., 2022). The general definition of stress is “when an individual perceives that the demands of an external situation are beyond his or her perceived ability to cope with them” (Jensen, 2012, p. 46). In addition, burnout is defined as “a state of exhaustion in which one is cynical about the value of one’s occupation and doubtful of one’s capacity to perform” (Maslach et al., 1996, p. 20). Burnout has been recognized as a modern occupational hazard due to its pervasiveness (Jamal, 2007; Jun et al., 2021; Kowalska et al., 2021; Maslach, 2003). Stress and burnout are detrimental to an individual’s well-being; in particular, their effects are more pronounced in entrepreneurship because of various stressors (e.g., financial, job, personal) an entrepreneur’s experience. One systematic literature review (Stephan, 2018) on entrepreneurship found that autonomy (i.e., freedom at work/flexibility) and stress were the two most studied entrepreneur-related work characteristics. Given the significance of stress and its accompanying outcomes, such as burnout, several scholars (e.g., Omrane et al., 2018; Palmer et al., 2021) have underscored the necessity for more research on stress and its associated results in an entrepreneurial context, which has been less understood than employment contexts (e.g., teachers, Conley & Woosley, 2000; Wei, Cang & Hisrich, 2015). For instance, entrepreneurial burnout has several negative consequences at various levels; individual (e.g., dissatisfaction with entrepreneurship) and economic/societal levels (e.g., firm closure) (Lerman et al., 2021; Wincent & Örtqvist, 2009a).

As noted, stress as a job characteristic of entrepreneurship has been researched to a certain extent (Stephan, 2018), considering multiple roles at each stage of the entrepreneurial process, a lack of resources and support from acquaintances could lead to experiencing stress and even burnout (Omrane et al., 2018). There is a consensus that prolonged stress experienced can lead to burnout (Omrane et al., 2018). The proposition is consistent with several stress-related theories (e.g., psychological stress theory, Biggs et al., 2017). However, it has been noted that stress experienced by entrepreneurs can have positive outcomes as well. For example, it has been maintained that several studies have found that some stressors experienced by entrepreneurs can be perceived as challenges (Patzelt & Shepherd, 2011; Stephan, 2018; Wei et al., 2015). Thus, the relationship between stress and burnout in entrepreneurship can be paradoxical (e.g., see Lerman et al., 2021; Stephan, 2018). Several researchers have expressed similar sentiments. For example, Lerman et al., 2021, pg. 373) noted, “Nearly four decades of research offered differing and ambiguous conclusions regarding the consequences of stress as it affects the entrepreneur and new ventures.” It is maintained that these paradoxical findings may be due to regression methods, where the analysis is based on sufficiency logic—that is, linear rationale, which attempts to determine whether an increase in the predictor variable is associated with an increase in the outcome variable (i.e., variance-based approaches such as correlation and regression analyses).

Consequently, in the present study, the entrepreneurial stress—burnout link was explored using a novel analytical method—Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA, Dul, 2016, 2019). Unlike regression methods (e.g., structural equation modeling), where analysis is based on sufficiency logic, the NCA is equipped to analyze based on the necessity logic. To this end, the current study investigated (1) the necessity of entrepreneurial stress as a precondition for entrepreneurial burnout; and (2) the necessity of entrepreneurial role stress (i.e., the tri-component conceptualization of role stress; Buttner, 1992) for burnout in an entrepreneurial context. Also, management scholars (e.g., Aguinis et al., 2020) have noted that the NCA technique can help future management researchers gain a clearer understanding of causal effects when examining a particular outcome, as well as help advance theory. As such, we label the present study as an exploratory study, which not only employs the NCA technique but also, at the same time, tests if the tri-component conceptualization of role stress (e.g., Buttner, 1992) is relevant to the entrepreneurial context.

This study is structured as follows. Firstly, we describe the theoretical background and research model that informs the study’s hypotheses. Secondly, we present the NCA logic and methodology and a concise explanation of the analyses. Thirdly, we present the method section, which describes the data gathering and the measures employed. Fourthly, NCA results are expounded. Finally, we conclude the manuscript with passages devoted to the study’s discussion and implications.

Theoretical background and hypotheses

Role stress and the Tri-Component conceptualization

A role theoretical approach (Biddle, 1986) emphasizes the character of individuals as social agents who acquire position-appropriate actions (Michaels et al., 1987). Consequently, every role (such as the personal role of being a parent or the professional role of being an entrepreneur) carries a certain amount of role stress (Wincent & Örtqvist, 2009a). This theoretical approach has been used to understand stress-related outcomes in various professions (e.g., teachers, engineers, caregivers, etc.) across the world (e.g., Japan, the USA, etc.) (Dubinsky et al., 1992; Wei et al., 2015). The role stress theory’s significance in entrepreneurship has been consistently maintained (Buttner, 1992; Wincent & Örtqvist, 2006, 2009a, b). Entrepreneurs, for instance, are social agents whose roles are determined by their role requirements or expectations (e.g., acting consistently with the expectations of customers, suppliers, and stakeholders; Wincent & Örtqvist, 2009a). Since an entrepreneurial journey entails invention, shifting from a concept to an established enterprise, and other boundary-spanning activities, role stress is a natural element of the entrepreneurial process (Wincent & Örtqvist, 2009a). Ideally, an entrepreneur will not experience role stress if they manage their role per the expectations of others (e.g., business partners or stakeholders). However, such a stress-free ideal entrepreneurial journey is sporadic, if not unattainable. According to studies, entrepreneurs face varying levels of role stress (e.g., Buttner, 1992; Jayasekara et al., 2020; St-Jean et al., 2022).

Based on the role stress conceptualization and related literature (e.g., Buttner, 1992), the tri-component conceptualization of role stress has been identified as optimal for entrepreneurial role stress (Buttner, 1992; Cardon & Patel, 2015; Wincent & Örtqvist, 2006, 2009a). This conceptualization refers to stress incurred by an entrepreneur due to three role dimensions, namely, entrepreneurial role conflict (i.e., incongruity or incompatibility in the role expectations or requirements; hereafter role conflict), entrepreneurial role ambiguity (i.e., clarity of role behavior to be performed; hereafter role ambiguity), and entrepreneurial role overload (i.e., due to lack of resources to perform the role; hereafter role overload) (Buttner, 1992; Wincent & Örtqvist, 2006; Wincent et al., 2008).Footnote 1

In general, several consequences of role stress are documented and have been investigated in organizational psychology, including job dissatisfaction (Smith & Brannick, 1990; Chen et al., 2007; Thakre & Shroff, 2016), turnover intentions (O’Driscoll & Beehr, 1994; Naidoo, 2018; Wen et al., 2020; Al-Mansour, 2021), and role burnout (Cordes et al., 1997; Shepherd et al., 2010; Tang & Li, 2021). Likewise, the tri-component conceptualization of role stress has been used in investigating entrepreneurs (e.g., Buttner, 1992; Wincent et al., 2008). Wincent et al. (2008) explored how the tri-component conceptualization of role stress influences entrepreneurial venture withdrawal, for example.

Role stress and burnout

In light of mentioned above, burnout can manifest in the form of exhaustion in various ways (e.g., emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decrease in personal accomplishments, Palmer et al., 2021; emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion, Fernet et al., 2016), which have been studied in the context of many professions (e.g., teachers/educators, Kim & Lambie, 2018; human rights activists, Chen & Gorski, 2015; Judges, Pereira et al., 2022; and mental healthcare staff, Johnson et al., 2018).

Extant literature has documented the detrimental effects of job burnout on human well-being (e.g., Schaufeli et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2022). In early burnout literature, Freudenberger noted, “Who is prone to burnout? The dedicated and the committed” (1974, p. 161). Lechat and Torres (2016) consistently stated that entrepreneurs are prime candidates for burnout. Given that entrepreneurs play many job roles (e.g., manager, seller, etc.) and meet corresponding role expectations (e.g., bankers, suppliers, etc.), this results in entrepreneurial burnout (Palmer et al., 2021). Consequently, entrepreneurial burnout refers to an “acute and prolonged professional stress” (Omrane et al., 2018, p. 30), Corroborated by several studies that have found a positive relationship between role stress and burnout in the context of entrepreneurship (Omrane et al., 2018; Palmer et al., 2021; Wincent & Örtqvist, 2009a), while Alarcon’s (2011) meta-analytic study found a negative association between role stress and burnout. Overall, it has been maintained that stress is a necessary conditionFootnote 2 for burnout. Per Lerman et al. (2021) meta-analytic study, role stress experienced by entrepreneurs per this conceptualization has been labeled as a hindrance stressor since it impacts their well-being negatively. In the present study, entrepreneurs were treated as a homogenous entity. And, based on the literature reviewed, the following hypothesis is being proposed:

-

H1: The presence of entrepreneurial role stress [overall] is a necessary condition for the presence of burnout among self-employed Americans (i.e., enabling logic).

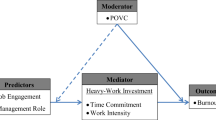

The conceptual model of the proposed necessity condition for role stress overall is depicted in Fig. 1.

Furthermore, the tri-component conceptualization of role stress (e.g., Buttner, 1992), and the role stress-burnout link literature (e.g., Omarane et al., 2018), the following hypotheses are being proposed:

-

H2a: The presence of entrepreneurial role conflict is a necessary condition for the presence of burnout among self-employed Americans (i.e., enabling logic).

-

H2b: The presence of entrepreneurial role ambiguity is a necessary condition for the presence of burnout among self-employed Americans. (i.e., enabling logic)

-

H2c: The presence of entrepreneurial role overload is a necessary condition for the presence of burnout among self-employed Americans. (i.e., enabling logic)

The conceptual model of the proposed necessity conditions is depicted In Fig. 2.

Method

Participants and procedures

Data were collected from self-identified adult entrepreneurs (i.e.,18 years or older) based in the United States using an online crowdsourcing data collection platform named Prolific (prolific.ac), which has been deemed as an appropriate source for data collection in social sciences (Palan & Schitter, 2018). In total, using convenience sampling, 328 self-identified entrepreneurs took part in the study. However, based on the survey completion and clearance of manipulation check questions, 285 (Male = 149; Mean age = 39.01 years, SD = 12.71) entrepreneurs' responses were analyzed for statistical purposes, mainly consisting of solo entrepreneurs (n = 203, 71%) with the majority of them (60%) reporting income of US$ 50,000 or less per annum. All participants were compensated with a nominal financial incentive for their participation. All participants completed a consent form at the beginning of the questionnaire battery describing the purpose of the study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were by the 1989 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Table 1 presents demographic data from study participants.

Overview of the NCA procedure

NCA aims to determine if there is a necessary (critical) determinant for an event to occur (Arenius et al., 2017; Dul, 2016, 2019). For instance, achieving the legal voting age is a necessary condition for voting. However, age is not a sufficient criterion as attitudes and knowledge, among other factors, impact voting propensity (Arenius et al., 2017; Cohen & Chaffee, 2013). Thus, the logic of NCA differs from that of linear rational, which attempts to determine whether an increase in the predictor variable is associated with an increase in the outcome variable (i.e., variance-based approaches such as correlation and regression analyses). NCA enables the identification of necessity in kind (e.g., ‘‘condition X is necessary or not for outcome Y”) and the concern for necessary relationships in degree (e.g., “a specific level of condition X is necessary or not for a specific level of outcome Y”) (Dul, 2016, 2019).

NCA application-related empirical studies can be found in various contexts (e.g., innovation in the buyer–supplier relationship, Van der Valk et al., 2016; lean manufacturing in small and medium enterprises, Knol et al., 2018; firm capabilities and performance, Tho, 2018; personality and impulsive buying behavior, Shahjehan & Qureshi, 2019; the emergence of motivation among schizophrenia spectrum disorder, Luther et al., 2017). For instance, the NCA method was used to determine whether intelligence is a necessary condition for creativity (Karwowski et al., 2016). Likewise, Arenius et al. (2017) employed the NCA method in the entrepreneurship context to understand the necessity of certain types of gestation activities for business formation.

The NCA method in a simple, dichotomous case (Dul, 2016, 2019) entails detecting a necessary condition (i.e., X is necessary for Y). It requires investigating in an XY scatterplot whether the intersection X = 0 and Y = 1 has no data points. If this intersection has data points, condition X is not necessary for Y. However, an in-depth analysis of the scatterplot(s) is recommended if X is necessary for Y. An in-depth analysis within the NCA technique involves two types of analyses—ceiling analysis and bottleneck analysis, which are explained in the following paragraphs briefly. The analyses mentioned above can also be extended to the context of ordinal and continuous variables (Dul, 2019). An exhaustive review of the NCA technique is beyond the scope of the present study; as such, the readers are referred elsewhere (see Dul, 2016, 2019).

There are two main recommended techniques to create ceiling lines within the NCA for the scatterplot (Dul, 2019), namely, the Ceiling-Regression-Free Disposal Hull (CR-FDH) and the Ceiling Envelopment-Free Disposal Hull (CE-FDH) (Dul, 2019). The CR-FDH technique creates a non-decreasing linear function that smooths the non-decreasing step function created by the second recommended technique (i.e., CE-FDH). Specifically, the CR-FDH method draws an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression trend line through the most upper-left data points in the scatterplot. However, since the CR-FDH is a smoothing technique and creates a straight ceiling line, it allows some data points to be above the ceiling line.

On the other hand, CE-FDH maximizes the area above the ceiling line that is the ceiling zone by assuming a non-decreasing (piecewise) linear ceiling, which results in no observation of empty space in the upper right corner of the scatterplot. As the ceiling zone with CE-FDH is left empty, the accuracy of this technique is 100 percent. Notably, these ceiling techniques differ from traditional regression-based approaches, where a best estimate average line is drawn through the middle of the data points (Dul, 2019). Furthermore, the NCA can also calculate a bottleneck table (Dul, 2019), which identifies the levels of X required for a given level of Y (i.e., when there is a bottleneck). More specifically, the bottleneck table identifies the specific minimum X level needed for different Y levels.

Finally, the NCA method calculates an effect size for a necessary condition. The effect size is the size of the ceiling zone divided by the scope (i.e., the entire area where data points are possible when considering the minimum and maximum levels of the independent variables—X) and dependent variables (i.e., Y) (Dul, 2019). According to Dul’s (2019) recommendations, an effect size of 0 < d < 0.1 represents a small effect, 0.1 ≤ d < 0.3 represents a medium effect, 0.3 ≤ d < 0.5 represents a large effect, and d ≥ 0.5 represents a very large effect.

Statistical packages

In the present study, two statistical software packages, namely SPSS 25.0 and NCA package, version 3.3. 1 (Dul, 2018; 2023) in R version 4.2.2, were used to conduct relevant statistical analyses; SPSS was used for descriptive statistics and reliability analyses. The NCA package conducted relevant NCA analyses such as scatterplot generation, process-related statistics, and bottleneck analyses.

Measurements

The survey consisted of Likert-type scales with items from existing scales used in previous studies (e.g., Wincent & Örtqvist, 2006).

The stress scale (Wincent & Örtqvist, 2006)

An 11-item entrepreneurial role stress scale was adopted from Wincent and Örtqvist (2006). It was rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = "Strongly Disagree" and 7 = "Strongly Agree"), which included 4-it4 items of role conflict, 4-it4 items of role ambiguity, and 3-it3 items of role overload. All the subscales, as well as the scale employed, demonstrated adequate reliability (i.e., α > 0.70) as reported by Wincent and Örtqvist (2006).

The burnout scale (Malach-Pines, 2005)

The burnout scale developed by Malach-Pines (2005) was also used. It consists of 10 items measured on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = "Never" and 7 = "Always"). Both study’s instruments were well-established and possessed adequate psychometric properties. For NCA purposes, composite scores were produced by averaging the number of items for a given construct, with more outstanding scores on a given construct representing higher levels. Malach-Pines (2005) reported that the burnout scale had adequate reliability when used in different samples (α > 0.80).

Results

Descriptive statistics and reliability

For descriptive statistics concerning the study sample, see Table 1 for an overview. The construct-related measurement scales in the present study demonstrated adequate internal reliability (Role conflict = 0.75; Role ambiguity = 0.86; Role overload = 0.79; Stress overallFootnote 3 = 0.82; and Burnout = 0.93; Nunnally, 1978).

The NCA method for testing the entrepreneurial role stress-burnout link

Figure 3 depicts the scatterplot for Role Stress [overall] versus burnout. The scatterplot in question contains a space in the upper left corner above the space with observations, suggesting the possible presence of a necessary condition. Figure 4 depicts the scatterplot for role overload and burnout, which does not have a space in the upper left corner, suggesting an absence of a necessary condition. Figure 2 is used to illustrate how scatterplot analysis helps in identifying if a necessary condition exists or not. Consistent with the role overload vs. burnout scatterplot, the scatterplots for role conflict and role ambiguity yielded comparable results (see Figs. 5 and 6). Thus, establishing that the three dimensions of role stress—role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload are not necessary for entrepreneurial role burnout. In Figs. 3, 4, 5, and 6, two ceiling lines are drawn (Dul, 2019), namely the ceiling envelopment technique (CE-FDH) and ceiling regression technique (CR-FDH), as noted earlier.

Additionally, Table 2 illustrates the bottleneck analysis, which shows all the necessary conditions for role stress [overall] and its related components (i.e., role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload) via their bottlenecks at various levels (or degrees) of burnoutFootnote 4. For example, per Table. 2, to attain a 50 percent level of burnout, it is necessary for an entrepreneur to experience at least 11 percent or higher on role stress, but experiencing role stress-related components (e.g., role overload) is not a necessary condition. Conversely, to experience 100 percent burnout, it is a necessary condition that an entrepreneur experience at least 71 percent role stress. The effect sizes for role stress (overall), role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload in the context of entrepreneurial burnout were d = 0.21 (p = 0.002), d = 0.13 (p = 0.189), d = 0.07 (p = 0.05), and d = 0.09 (p = 0.112) respectively. Based on the effect sizes and p-value significance proposed by Dul (2019), the overall role stress (i.e., composite) effect size is medium and statistically significant at p < 0.05. On the other hand, the effect sizes of role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload are not necessary for entrepreneurial burnout since their effect sizes failed to reach statistical significance at p < 0.05.

These findings can be explained with an analogy (Dul, 2019). For example, a ‘red apple’ is not necessary for an apple pie, and green apple is not necessary for an apple pie. However, the higher-order construct (apple) is necessary. Thus, it is possible to formulate the necessary condition hypothesis with the higher-order concept. Similarly, role stress is a necessary condition to experience entrepreneurial burnout. But entrepreneurial role stress as conceptualized consistent with the tri-component model of role stress (e.g., role overload, etc.; Buttner, 1992) is not a necessary condition for entrepreneurial burnout.

Discussion

The present study investigated the relationship between stress and burnout, mainly the necessity of role stress to experience burnout in an entrepreneurship context. Based on the role stress theory, the study also investigates the necessary condition of the tri-component conceptualization of role stress (e.g., Buttner, 1992) using the NCA method (Dul, 2016, 2019).

To this end, consistent with the variance-based approach (e.g., regression analysis) studies, in the present study it was found that overall role stress is a necessary condition for entrepreneurial role burnout. An entrepreneur must experience role stress before one experience's role burnout. Several NCA-related statistics support the necessary condition. For example, the effect size (d = 0.21, p = 0.002) was moderate and statistically significant for the role stress-burnout relationship.

Since the necessity condition was moderate and statistically significant for overall role stress and burnout, the next step of the NCA method was to investigate the necessary conditions of the role stress dimensions’ (e.g., role overload) necessary conditions for burnout among entrepreneurs. Per the NCA results, it was found that none of the three dimensions of role stress (i.e., role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload) were necessary conditions for entrepreneurs to experience role burnout. In other words, the tri-component conceptualization of role stress in entrepreneurship does not necessarily lead to burnout based on necessity logic. The NCA-related statistics support the assertion mentioned above. The effect sizes of role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload were, for example, irrelevant since they failed to reach the statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Our finding is in stark contrast to previous studies that investigate the entrepreneurial role stress-burnout link based on sufficiency logic (e.g., regression analysis) using the role theory’s stress conceptualization. Per the NCA, although entrepreneurial role stress is an essential prerequisite to experience burnout, conceptualizing role stress by the tri-component conceptualization is insufficient because role stress may result from factors other than the three dimensions proposed in the literature. For example, entrepreneurship literature (Lerman et al., 2021; Stephan, 2018) has noted that entrepreneurs encounter unique stressors compared to non-entrepreneurs, impacting them differently. For example, entrepreneurs spend long hours at work, which impacts their work-life balance (Jiang et al., 2018). Also, Lerman et al. (2021) noted that entrepreneurs experience stressors, which may contribute to their well-being (i.e., challenge stressors) as well as the ones that contribute to a decrement in their well-being (i.e., hindrance stressors). Thus, stress can have positive and negative consequences, particularly entrepreneurship.

Our NCA analysis revealed that role stress for entrepreneurs as conceptualized by role stress theory is not a necessary condition for entrepreneurs to experience burnout. In other words, role conflict, role overload, and role ambiguity are labeled as hindrance stressors (see Lerman et al., 2021) because typically these stressors in a non-entrepreneurship context have demonstrated that they cause role burnout. However, given the unique characteristics of entrepreneurship, these factors are not necessary conditions for entrepreneurs to experience burnout. We attribute this finding to the nature of entrepreneurship. It is extremely likely that entrepreneurs view these stressors as a part of their job and have superior coping mechanisms (Lerman et al., 2021). Also, in recent years, role stress might stem from other factors such as negative affect (Cardon & Patel, 2015) and anxiety/fear (Cacciotti & Hayton, 2015), warranting additional study.

Implications

The present study investigated the relationship using necessity logic (as opposed to sufficiency logic) using a novel statistical method (i.e., NCA, Dul, 2016, 2019). Results indicated that role stress [overall] is a necessary condition for burnout in entrepreneurial contexts. However, comparable results were not found for the tri-component conceptualization of role stress, which has been documented as a necessary and sufficient condition for role stress and its associated outcomes by other researchers (e.g., Buttner, 1992). To this end, some theoretical and methodological implications could be discussed.

Theoretically, future studies should frame the concept of entrepreneurial role stress in a broader, going beyond the tri-component conceptualization of role stress. In addition, a more general broader conceptualization of entrepreneurial role stress has implications for burnout research and can facilitate gaining a fine-grained understanding of entrepreneurial well-being.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the stress—burnout link in entrepreneurship using the NCA method (Dul, 2016, 2019). The NCA appears to be a more helpful and appropriate tool for determining necessity, an alternative to the widely employed correlation and regression analyses (Karwowski et al., 2016). For instance, in a typical sufficiency-based statistical method, role stress and its three dimensions (i.e., role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload) are positively associated with burnout. Nevertheless, these average-based estimation approaches could mask the actual relationships between the constructs analyzed (e.g., role stress dimensions and burnout). Future studies are encouraged to complement the sufficiency logic analyses (e.g., regression analyses and structural equation modeling) with the necessary logic (i.e., NCA, Dul, 2016, 2019) better to understand the nuanced relationships between the study variables.

Limitations

Even though the current study's use of the NCA approach, as opposed to linear methodologies, is a strength, it also has some limitations. Consistent with the limitation of observational research, causality could not be determined. NCA may be more prone to sampling and measurement errors than conventional data analysis techniques. For drawing the ceiling line, the proposed ceiling techniques utilize only a tiny fraction of the sample's data (the observations near the ceiling line). The ceiling line (and thus other metrics derived from it, such as effect size and accuracy) may be susceptible to selection bias and measurement error in the situations around the ceiling line. This is especially true if the number of cases near the ceiling line is small. Therefore, the accuracy of the ceiling line is dependent on having representative cases with precise variable measurements surrounding the ceiling line. Given the size of the sample, the sample's representativeness, and the well-established measurements, however, it is possible that these constraints do not apply to our study. Finally, the inability to assure temporality in cross-sectional data also would temper the conclusions drawn.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available.

Notes

Per a meta-analytic study (Alarcon, 2011) that focused on role theory and burnout found that role ambiguity (ρ = .32, k = 51, N = 22,145), role conflict (ρ = .53, k = 37, N = 13,568), and workload (ρ = .49, k = 86, N = 51,529) were positively associated with burnout.

A necessary condition is a condition that must be present to enable a specific outcome; without the condition, the outcome will be absent (Dul, 2019).

Stress overall consisted of all the eleven items related to role conflict, role ambiguity, and role overload constructs.

For the sake of simplicity only CR-FDH results are discussed. Also, CR-FDH results are highly relevant for continuous variables (Dul, 2020).

References

Adisa, T. A., Gbadamosi, G., Mordi, T., & Mordi, C. (2019). In search of perfect boundaries? Entrepreneurs’ Work-Life Balance. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-06-2018-0197

Aguinis, H., Ramani, R. S., & Cascio, W. F. (2020). Methodological practices in international business research: An after-action review of challenges and solutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 51, 1593–1608. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-020-00353-7

Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007

Al-Mansour, K. (2021). Stress and turnover intention among healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia during the time of COVID-19: Can social support play a role? PloS One, 16(10), e0258101. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258101

Amorós, J. E., Cristi, O., & Naudé, W. (2021). Entrepreneurship and subjective well-being: Does the motivation to start-up a firm matter? Journal of Business Research, 127, 389–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.044

Anderson, A. R., & Warren, L. (2011). The entrepreneur as hero and jester: Enacting the entrepreneurial discourse. International Small Business Journal, 29(6), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242611416417

Arenius, P., Engel, Y., & Klyver, K. (2017). No particular action needed? A necessary condition analysis of gestation activities and firm emergence. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.07.004

Baron, R. A., Franklin, R. J., & Hmieleski, K. M. (2016). Why entrepreneurs often experience low, not high, levels of stress: The joint effects of selection and psychological capital. Journal of Management, 42(3), 742–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313495411

Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 12(1), 67–92. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.12.080186.000435

Biggs, A., Brough, P., & Drummond, S. (2017). Lazarus and Folkman's psychological stress and coping theory. The handbook of stress and health: A guide to research and practice, 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118993811.ch21

Buttner, E. H. (1992). Entrepreneurial stress: Is it hazardous to your health? Journal of Managerial Issues, 4(2), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.2307/40603932

Cacciotti, G., & Hayton, J. C. (2015). Fear and entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(2), 165–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12052

Cardon, M. S., & Patel, P. C. (2015). Is stress worth it? Stress-related health and wealth trade-offs for entrepreneurs. Applied Psychology, 64(2), 379–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12021

Chen, C. W., & Gorski, P. C. (2015). Burnout in social justice and human rights activists: Symptoms, causes and implications. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 7(3), 366–390. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhuman/huv011

Chen, Y. M., Chen, S. H., Tsai, C. Y., & Lo, L. Y. (2007). Role stress and job satisfaction for nurse specialists. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59(5), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04339.x

Cohen, A. K., & Chaffee, B. W. (2013). The relationship between adolescents’ civic knowledge, civic attitude, and civic behavior and their self-reported future likelihood of voting. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice, 8(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197912456339

Conley, S., & Woosley, S. A. (2000). Teacher role stress, higher order needs and work outcomes. Journal of Educational Administration, 38(2), 179–201.

Cordes, C. L., Dougherty, T. W., & Blum, M. (1997). Patterns of burnout among managers and professionals: A comparison of models. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 18(6), 685–701. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199711)18:6%3C685::AID-JOB817%3E3.0.CO;2-U

Cunningham, J., & Fraser, S. S. (2022). Images of entrepreneurship: divergent national constructions of what it is to ‘do’entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2022.2071997

Das, A. K. (2011). Organizational role-stress: A critical review. Social Science International, 27(1), 131–134.

Dubinsky, A. J., Michaels, R. E., Kotabe, M., Lim, C. U., & Moon, H. C. (1992). Influence of role stress on industrial salespeople’s work outcomes in the United States, Japan and Korea. Journal of International Business Studies, 23, 77–99.

Dul, J. (2016). Necessary condition analysis (NCA) logic and methodology of “necessary but not sufficient” causality. Organizational Research Methods, 19(1), 10–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115584005

Dul, J. (2019). Conducting necessary condition analysis for business and management students. SAGE Publications Limited.

Dul, J. (2018). Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) with R (version 3.0. 1, August, 2018) A quick start guide.

Fernet, C., Torrès, O., Austin, S., & St-Pierre, J. (2016). The psychological costs of owning and managing an SME: Linking job stressors, occupational loneliness, entrepreneurial orientation, and burnout. Burnout Research, 3(2), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2016.03.002

Forson, C. (2013). Contextualising migrant black business women’s work-life balance experiences. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 19(5), 460–477. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-09-2011-0126

Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues, 30(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2018). GEM Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2018-2019-global-report

Guberina, T., & Wang, A. M. (2021). Entrepreneurial leadership impact on job security and psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A conceptual review. International Journal of Innovation and Economic Development, 6(6), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.18775/ijied.1849-7551-7020.2015.66.2001

Jamal, M. (2007). Burnout and self-employment: A cross-cultural empirical study. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 23(4), 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1144

Jayasekara, B. E. A., Fernando, P. N. D., & Ranjani, R. P. C. (2020). A systematic literature review on financial stress of small and medium entrepreneurs. Applied Economics and Business, 4(1), 45–59.

Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2013.782190

Jensen, S. M. (2012). Psychological Capital: Key to understanding entrepreneurial stress. Economics & Business Journal: Inquiries & Perspectives, 4(1), 44–55.

Jiang, D. S., Kellermanns, F. W., Munyon, T. P., & Morris, M. L. (2018). More than meets the eye: A review and future directions for the social psychology of socioemotional wealth. Family Business Review, 31(1), 125–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486517736959

Johnson, J., Hall, L. H., Berzins, K., Baker, J., Melling, K., & Thompson, C. (2018). Mental healthcare staff well-being and burnout: A narrative review of trends, causes, implications, and recommendations for future interventions. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12416

Jun, J., Ojemeni, M. M., Kalamani, R., Tong, J., & Crecelius, M. L. (2021). Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organizational outcomes: Systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 119, 103933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103933

Kalden, J. N., Cunningham, J., & Anderson, A. R. (2017). The social status of entrepreneurs: Contrasting German perspectives. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 18(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750317706439

Karwowski, M., Dul, J., Gralewski, J., Jauk, E., Jankowska, D. M., Gajda, A., Chruszczewski, M. H., ... & Benedek, M. (2016). Is creativity without intelligence possible? A necessary condition analysis. Intelligence, 57, 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2016.04.006

Kim, N., & Lambie, G. W. (2018). Burnout and implications for professional school counselors. Professional Counselor, 8(3), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.15241/nk.8.3.277

Knol, W. H., Slomp, J., Schouteten, R. L., & Lauche, K. (2018). Implementing lean practices in manufacturing SMEs: Testing ‘critical success factors’ using Necessary Condition Analysis. International Journal of Production Research, 56(11), 3955–3973. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1419583

Kowalska, J., Chybowski, D., & Wójtowicz, D. (2021). Analysis of the sense of occupational stress and burnout syndrome among working physiotherapists—a pilot study. Medicina, 57(12), 1290. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57121290

Lanivich, S. E., Bennett, A., Kessler, S. R., McIntyre, N., & Smith, A. W. (2021). RICH with well-being: An entrepreneurial mindset for thriving in early-stage entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Research, 124, 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.036

Lechat, T. & Torres, O. (2016). Exploring negative affect in entrepreneurial activity: Effects on emotional stress and contribution to burnout. In Emotions and organizational governance. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1746-979120160000012003

Lerman, M. P., Munyon, T. P., & Williams, D. W. (2021). The (not so) dark side of entrepreneurship: A meta-analysis of the well-being and performance consequences of entrepreneurial stress. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 15(3), 377–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1370

Li, C., Meng, C. F., & Chen, H. L. (2021). Research on the Influence Mechanism of Role Overload on Entrepreneurial Burnout--Use SEM structural equation and SPSS software. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 251, p. 01028). EDP Sciences.

Luther, L., Bonfils, K. A., Firmin, R. L., Buck, K. D., Choi, J., Dimaggio, G., Popolo, R., Minor, K. S., & Lysaker, P. H. (2017). Metacognition is necessary for the emergence of motivation in people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A necessary condition analysis. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(12), 960–966. https://doi.org/10.1097/2FNMD.0000000000000753

Malach-Pines, A. (2005). The burnout measure, short version. International Journal of Stress Management, 12(1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.12.1.78

Manzano-García, G., Ayala-Calvo, J. C., & Desrumaux, P. (2021). Entrepreneurs’ capacity for mentalizing: its influence on burnout syndrome. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/2Fijerph18010003

Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 189–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01258

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). MBI: Maslach burnout inventory. CPP Incorporated.

Michaels, R. E., Day, R. L., & Joachimsthaler, E. A. (1987). Role stress among industrial buyers: An integrative model. Journal of Marketing, 51(2), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298705100203

Montanari, F., Mizzau, L., & Razzoli, D. (2021). ‘Start me up’: the challenge of sustainable cultural entrepreneurship for young cultural workers. In Cultural Initiatives for Sustainable Development (pp. 143–160). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65687-4_7

Naidoo, R. (2018). Role stress and turnover intentions among information technology personnel in South Africa: The role of supervisor support. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v16i0.936

Nambisan, S., & Baron, R. A. (2021). On the costs of digital entrepreneurship: Role conflict, stress, and venture performance in digital platform-based ecosystems. Journal of Business Research, 125, 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.037

Nikolaev, B. N., Lerman, M. P., Boudreaux, C. J., & Mueller, B. A. (2022). Self-employment and eudaimonic well-being: The mediating role of problem- and emotion-focused coping. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/10422587221126486

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

O’Driscoll, M. P., & Beehr, T. A. (1994). Supervisor behaviors, role stressors and uncertainty as predictors of personal outcomes for subordinates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150204

Omrane, A., Kammoun, A., & Seaman, C. (2018). Entrepreneurial burnout: Causes, consequences and way out. FIIB Business Review, 7(1), 28–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2319714518767805

Palan, S., & Schitter, C. (2018). Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 17, 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2017.12.004

Palmer, C., Kraus, S., Kailer, N., Huber, L., & Öner, Z. H. (2021). Entrepreneurial burnout: A systematic review and research map. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 43(3), 438–461. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2021.115883

Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2011). Negative emotions of an entrepreneurial career: Self-employment and regulatory coping behaviors. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(2), 226–238.

Pereira, S. P. M., Correia, P. M. A. R., Da Palma, P. J., Pitacho, L., & Lunardi, F. C. (2022). The conceptual model of role stress and job burnout in judges: The moderating role of career calling. Laws, 11(3), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws11030042

Quiun, L., Herrero, M., del Carmen Yeo Ayala, M., & Moreno-Jiménez, B. (2022). Entrepreneurs and burnout. How hardy personality works in this process. Psychological Reports, 125(3), 1269–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294121996978

Ross, J., Strevel, H., & Javadizadeh, B. (2021). Don’t stop believin’: The journey to entrepreneurial burnout and back again. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 33(5), 559–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2020.1717897

Schaufeli, W. B., Maslach, C., & Marek, T. (Eds.). (2017). Professional burnout: Recent developments in theory and research. Routledge.

Shahjehan, A., & Qureshi, J. A. (2019). Personality and impulsive buying behaviors. A necessary condition analysis. Economic research-Ekonomska istraživanja, 32(1), 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2019.1585268

Sheehan, C.-A., & St-Jean, E. (2014). La santé des entrepreneurs: Une scoping study [The health of entrepreneurs: A scoping study]. Paper presented at the 12th Congrès International Francophone en Entrepreneuriat et PME (CIFEPME), 27–29 October, Agadir, Maroc.

Shepherd, C. D., Marchisio, G., Morrish, S. C., Deacon, J. H., & Miles, M. P. (2010). Entrepreneurial burnout: Exploring antecedents, dimensions and outcomes. Journal of Research in Marketing and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/14715201011060894

Shir, N., Nikolaev, B. N., & Wincent, J. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: The role of psychological autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.05.002

Smith, C. S., & Brannick, M. T. (1990). A role and expectancy model of participative decision-making: A replication and theoretical extension. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110202

Stephan, U. (2018). Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(3), 290–322. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0001

St-Jean, E., Tremblay, M., Barès, F., & Simionato, M. (2022). Effect of nascent entrepreneurs' training on their stress: the role of gender and participants' interaction. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship, (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/NEJE-10-2021-0064

Tang, X., & Li, X. (2021). Role stress, burnout, and workplace support among newly recruited social workers. Research on Social Work Practice, 31(5), 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731520984534

Thakre, N., & Shroff, N. (2016). Organizational climate, organizational role stress and job satisfaction among employees. Journal of Psychosocial Research, 11(2), 469–478.

Tho, N. D. (2018). Firm capabilities and performance: A necessary condition analysis. Journal of Management Development, 37(4), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-06-2017-0204

Torrès, O., Benzari, A., Fisch, C., Mukerjee, J., Swalhi, A., & Thurik, R. (2022). Risk of burnout in French entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 crisis. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 717–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00516-2

Van der Valk, W., Sumo, R., Dul, J., & Schroeder, R. G. (2016). When are contracts and trust necessary for innovation in buyer-supplier relationships? A necessary condition analysis. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 22(4), 266–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2016.06.005

Wei, X., Cang, S., & Hisrich, R. D. (2015). Entrepreneurial stressors as predictors of entrepreneurial burnout. Psychological Reports, 116(1), 74–88. https://doi.org/10.2466/01.14.PR0.116k13w1

Wen, B., Zhou, X., Hu, Y., & Zhang, X. (2020). Role stress and turnover intention of front-line hotel employees: The roles of burnout and service climate. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00036

Wiklund, J., Hatak, I., Patzelt, H., & Shepherd, D. A. (2018). Mental disorders in the entrepreneurship context: When being different can be an advantage. Academy of Management Perspectives, 32(2), 182–206. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0063

Wiklund, J., Nikolaev, B., Shir, N., Foo, M. D., & Bradley, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(4), 579–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.01.002

Wincent, J., & Örtqvist, D. (2006). Analyzing the structure of entrepreneur role stress. Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, 18(2), 1–21.

Wincent, J., & Örtqvist, D. (2009a). A comprehensive model of entrepreneur role stress antecedents and consequences. Journal of Business and Psychology, 24(2), 225–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-009-9102-8

Wincent, J., & Örtqvist, D. (2009b). Role stress and entrepreneurship research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 5(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-006-0017-9

Wincent, J., Örtqvist, D., & Drnovsek, M. (2008). The entrepreneur’s role stressors and proclivity for a venture withdrawal. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 24(3), 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2008.04.001

Zhou, T., Xu, C., Wang, C., Sha, S., Wang, Z., Zhou, Y., ... & Wang, Q. (2022). Burnout and well-being of healthcare workers in the post-pandemic period of COVID-19: a perspective from the job demands-resources model. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07608-z

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were by the 1989 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

All participants completed a consent form at the beginning of the questionnaire battery describing the purpose of the study.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced this work.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Manchiraju, S., Akbari, M. & Seydavi, M. Is entrepreneurial role stress a necessary condition for burnout? A necessary condition analysis. Curr Psychol 43, 4766–4778 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04704-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04704-z