Abstract

Although altruistic lies are considered moral, they can result in negative outcomes. In this study, we explored the effect of prior altruistic lying on subsequent self-interested lying. In Studies 1 and 2, we found a moral balance effect that individuals who previously chose to tell altruistic lies subsequently told more self-interested lies, while those who previously chose to be honest against helping others subsequently told fewer self-interested lies. In Study 3, we explored how attribution style influenced the effect of moral balance, revealing that the moral balance effect disappeared for the externally attributed participants. In Study 4, we examined whether contextual similarity affects the moral balance effect. We found that the moral balance effect disappeared when participants were directed to pay attention to differences between the self-interested and altruistic lying tasks. This research first included altruistic lies in the consideration of moral continuity, expanding the understanding of ethical behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although lying is considered immoral behavior since it goes against the moral principle of honesty, people sometimes tend to lie for their own benefit by, for example, cheating on exams or evading taxes. However, in addition to self-interested lying, people also lie to benefit others, which is known as altruistic lying. In most cases, an altruistic lie is accepted as moral behavior. Previous studies even found that it was even considered as being more moral and acceptable than self-interested honesty (Dunbar et al., 2016; Levine & Schweitzer, 2014). However, regardless of whether the outcome is beneficial to the self or others, lying still violates the norm of honesty. Therefore, it is reasonable to question whether altruistic lies have any detrimental effects on individuals. In this research, we include altruistic lies in the consideration of moral behavior continuity to broaden the discussion of moral topics by exploring the influence of prior altruistic lying behaviors on subsequent self-interested lying behaviors.

Theoretical background

Altruistic lies are told to benefit the recipient (Erat & Gneezy, 2012). From an early age, we are taught to tell friendly lies to be polite (Talwar et al., 2007). Approximately 20% of people lie during interpersonal interactions (DePaulo & Bell, 1996), and most of these lies are prosocial (DePaulo & Kashy, 1998; Iezzoni et al., 2012; Palmieri & Stern, 2009) While altruistic lies are told with good intentions and lead to good outcomes, the act of lying itself still violates the principles of honesty and fairness, which is unethical. Therefore, altruistic lies are ambiguous and conflict with the domain of moral evaluation. Taking this moral dilemma into account, previous studies have found that the comprehensive evaluation of altruistic lying has mostly focused on their outcomes, considering them to be a more moral act even than honesty (Erat & Gneezy, 2012; Levine & Schweitzer, 2014).

Although altruistic lies are relatively more acceptable, they still violate the natural preference for people to “remain honest” (Levine & Munguia Gomez, 2021; Vanberg, 2008), so there are still potential costs to telling them. Some scholars have found that the phenomenon of lie aversion exists, wherein people refuse to lie regardless of whether it is an altruistic lie or both a self-interested and altruistic lie (Erat & Gneezy, 2012). This also reflects two different views on the ethical decision-making process. Some scholars suggest that morality is a stable personal trait (Aquino & Reed, 2002), and that dishonesty is a character flaw that only few people possess. However, other studies provide conflicting evidence that situational factors are more important than individual differences. Moral people act immorally under some circumstances (Gino & Ariely, 2016), and dishonest people will perform good deeds to restore their moral reputation (Pagliaro et al., 2016). Thus, morality is dynamic; even individuals with strong moral values will not behave the same way in different situations (Monin & Jordan, 2009).

In the case of altruistic lies, refusing to lie would indicate that the participants refuse to help others in order to maintain their own moral self-image. In contrast, those who lie believe that they are sacrificing their own standard of honesty to do good for others. Although altruistic lying is considered worthy of promotion, it is still essentially deceptive behavior. Will altruistic lying bring about a moral decline in the long run and trigger more lying especially self-interested lying afterwards?

Previous research on altruistic lies has focused on their positive aftereffect (Iniguez et al., 2014), such as that they can promote trust (Levine & Schweitzer, 2014), or protect the receiver’s feeling and provide interpersonal support (Cheung et al., 2016; Dunbar et al., 2016; Ennis et al., 2008). However, such studies usually only examined the effects of altruistic lies on the recipients’ emotions or behaviors, and ignored their effects on the liars themselves.

In addition, previous research on the effect of prior (im)moral behavior on subsequent (im)moral behavior has been limited to self-interested lies or prosocial behaviors, which is moral or immoral in terms of intent, behavior, and outcome as a whole. However, the reality of moral or immoral behavior is often not black and white; for example, there are cases wherein people avoid telling the other person the truth because they sympathize with what they are going through (Lupoli et al., 2017). Since the intention and outcome of altruistic lies are conflicted based on moral evaluation, examining their effect on subsequent self-interested lying behaviors can help us better grasp moral situations in reality.

Currently, there are two theories regarding the consistency of moral behavior: moral consistency theory and moral balance theory. First, the moral consistency theory proposes that individuals who were previously honest may continue to follow the principle of honesty in order to maintain moral consistency. Second, the moral balance theory proposes that individuals who behaved unethically before may do so less through moral cleansing to compensate for unethical behaviors, whereas those who behaved ethically before may also appear to possess the moral license to behave unethically afterwards (Mullen & Monin, 2016).

Although the moral consistency theory and moral balance theory conceptually contradict each other, both theories are supported by evidence. If both theories are correct, it may be possible to integrate them. The next section shows a comparison of the moral consistency theory and moral balance theory via a literature review of both theories. The review will examine the current understanding of these theories, their differences, and their potential applications. In addition, the study will also adopt the construal level theory to integrate these theories and provide insights into their practical application in the current research context.

Moral consistency theory

Theories of social psychology have supported the idea of individuals’ consistency for a long time. Psychologists argued that people have a need for cognitive consistency and want to maintain a harmonious evaluation in all areas of their lives, and that any inconsistency would bring psychological discomfort (Festinger, 1957).

Theories about self-perception suggest that people’s attitudes toward morality and their actual moral behavior are usually congruent. On the one hand, people figure out their attitudes and feelings by observing their own behaviors (Bem, 1972). On the other hand, their ideas can guide their subsequent actions. People who regard themselves as moral remind themselves that they should continue to behave morally so as not to undermine their own self-concept (Blasi, 1980). In fact, numerous empirical studies have supported this moral reinforcement effect. For example, when people are directed to focus on specific aspects of their self-concept, such as being helpful, they are motivated to adopt corresponding helpful behaviors (Kraut, 1973; Stone & Cooper, 2001). (Nelson & Norton, 2005) also found that, compared to the control group, when participants were directed to focus on and describe superheroes, they were more willing to engage in volunteerism in the future. In addition, (Young et al., 2012) found the same results in the domain of prosocial behaviors.

Further, moral self-image has been found to play a reinforcing role in moral behavior. When people consciously remind themselves that they are good people after committing moral acts, they would do more good things (Young et al., 2012). The moral self involves the morality of self-identity (the qualities of the individuals themselves), which includes one’s self-perception and identity (“who I am”), and ways of thinking, feeling, and regulating behavior (“how I behave”) (Baumeister, 1987). Theories about the moral self have been summarized by scholars. Individuals seek to align such theories with their own conception of the moral self, therefore motivating their behaviors in various situations to correspond with their moral principles (Jennings et al., 2015). Viewing oneself as moral makes people engage in more prosocial behaviors (Conway & Peetz, 2012; Cornelissen et al., 2008; Patrick et al., 2018), and moral behaviors in turn reinforce and enhance one’s moral self-image (Benoît Monin & Jordan, 2009).

Moral balance theory

Although the consistency theory has been accepted by academics for a long time, moral balance theory have presented evidences that have challenged it. The moral balance theory suggested that individuals could receive a psychological license to act immorally by displaying some moral behaviors at first (Lasarov & Hoffmann, 2020; Merritt et al., 2010). For example, (Monin & Miller, 2001) found that participants who previously opposed sexism were more likely to reflect the gender stereotype in a later task by choosing a man rather than a woman for an assignment. Some researchers also found that individuals who supported Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential election were less likely to show unbiased attitudes toward Black people and indicated that White people were more suited to become police officers (Effron et al., 2009).

In addition to these unconsciously flowing biased statements, individuals’ behaviors were also influenced by prior displays of (im)moral acts. In the Dictator game, giving behaviors could influence subsequent giving decisions, and people will exhibit altruism after showing selfishness, or being selfish after being altruistic ((Brañas-Garza et al., 2013). People even systematically use their ethical license to achieve their own objectives. If people know that they may need moral permission to perform an unethical act, they will strategically seek opportunities that will allow them to act ethically first (Effron & Monin, 2010).

These studies show a substantial licensing effect in moral continuity, in which individuals behave more unethically after exhibiting ethical behavior. They feel good about themselves for having done something ethical, thus letting down their guard, justifying immoral behaviors, showing preferences based on intuition, and rewarding themselves by doing something unethical (Yam et al., 2017).

By contrast, since people need to maintain a moral self-image, they sometimes constantly give excuses and explanations to project a self-image that is more moral after displaying unethical behavior (Steele, 1988), such as “I behaved unethically because a moral act could counteract it.” However, if the cheating behavior is prohibited, it will promote individuals’ self-evaluation and increase their morality (Vallacher & Solodky, 1979).

Another moral balance effect is the cleansing effect (moral compensation effect), which proposed that people are more likely to eliminate guilt by physically or behaviorally cleansing themselves after committing an immoral act. (Zhong & Liljenquist, 2006) found that participants were more likely to choose a cleaning product (e.g., disinfectant wipes) as a gift after recalling past immoral acts because physical cleansing can mitigate the consequences of immoral behavior and the threats to a moral self-image. Other researchers also confirmed this phenomenon (Gollwitzer & Melzer, 2012).

Besides physical cleansing, people also engage in mental compensation. After their moral identity is threatened, they become more willing to engage in altruistic acts as a way to regain their self-worth (Sachdeva et al., 2009). For example, (Schei et al., 2019) found that participants who recall on overeating have more willingness to participate in prosocial behaviors at the cost of self-sacrificing than those who recall on neutral things.

Comparison of two theories

(Conway & Peetz, 2012) argued that the level of construal might determine whether prior behavior brings about moral consistency or moral balance. The construal level theory by (Trope & Liberman, 2010) proposed that the psychological distant influence the style of thinking and explanations. When things or behaviors are in a close psychological distant, individuals are more likely to thinking concretely (low level of construal) and focus on how to execute a behavior in a specific situation; whereas when in a far psychological distant, individuals are more likely to thinking abstractly and focus on the value and traits behind behaviors (Eyal et al., 2009). (Conway & Peetz, 2012) found the moral balance theory was supported by results if participants recalled a recent event (i.e., within 1 week); whereas the moral consistency theory was supported if participants recalled a distant event (i.e., over 1 year ago). Another study about prosocial behaviors also found a similar result that abstract thinking fostered moral consistent behaviors (Henderson & Burgoon, 2014). Basically, the core view of the construal level theory is, a high-level construal and abstract mindset leads to a focus on goals and values, bringing about moral consistency, whereas a low-level construal and concrete focus on behaviors and consequences leads to moral balance (Mullen & Monin, 2016).

Therefore, according to the construal level theory, if the time interval between prior (im)moral behavior and subsequent (im)moral behavior is short, moral balance will take effect. The present study aimed to confirm this effect by examining how prior altruistic lies affect subsequent selfish lies. While altruistic lies are generally perceived as ethical behavior, selfish lies are considered unethical. Therefore, if individuals are confronted with a self-interest lying situation just after performing altruistic lies (a close psychological distance), they are more likely to be influenced by a low-level construal and make a selfish lying decision. The next section further discusses the designs and hypotheses of the present study in detail.

Prior altruistic lie and subsequent selfish lie

Self-interested lies are defined as false statements that aim at misleading others and benefiting one self (Levine & Schweitzer, 2014). Self-interested lies violate the principle of honesty, and show selfishness at the same time, sometimes even with the cost of hurting others (Levine & Schweitzer, 2015). It’s a typical immoral behavior with opposite intentions and results from altruistic lies.

Since these two behaviors were successive performed without long-term pause in our study, it is reasonable to believe that participants will consider the situation at a lower level of construal and generate a moral balance effect. Because in altruistic lying, “lying” and “altruism” are both moral things, so it depends on how participants perceive them generally. As we discussed above, previous study shows that altruistic lying is seen as a moral behavior (Levine & Schweitzer, 2014). Therefore, participants who perform altruistic lie first are more likely to perform selfish lies.

According to moral balance theory, prior moral behaviors bring a psychological license to individuals, thus individuals have a strong justification to perform consequent ethically problematic attitudes or behaviors (Lasarov & Hoffmann, 2020; Miller & Effron, 2010). Those underlying mechanism was similar with the moral disengagement. (Bandura, 1999) raised moral disengagement concept as a cognitive mechanism that prohibits moral self-regulatory process and allow individuals to do immoral things. According to this theory, individuals can use this mechanism to reexplain their immoral behaviors in an acceptable way, so that they will not feel guilty and still see themselves as moral people. Previous studies found that participants with high moral disengagement propensity are less likely to help others (Bandura et al., 1996; Paciello et al., 2013) and more likely to behavior immorally (Detert et al., 2008; Moore et al., 2012). Therefore, we propose that the relationship between previous altruistic lying and subsequent self-interested lying can be explained by moral disengagement mechanism, especially by the moral justification process. As for altruistic lies, since the consequence is to help others, individuals will evoke the moral disengagement to justify the part of dishonest behavior. If this justification was transferred to a selfish lie situation, it could give individuals license to tell more lies for their own benefits. Therefore, we hypothesized that:

-

Hypothesis 1a: Individuals who previously chose to tell more altruistic lies would later tell more self-interested lies than those who do not tell altruistic lies.

-

Hypothesis 1b: The. moral disengagement plays a mediating role in this relationship between prior altruistic lies and consequent self-interested lies.

Attribution and moral balance

Previous literature on moral balance clarified that moral behavior is often displayed by the participants themselves, holding them responsible for their own choices. Individuals need to commit a moral act to counteract an immoral one and mitigate the threat to their self-image. However, if they believe that the unethical act was not determined by their own will, it is possible that the threat to their moral self-image would be too small to evoke a compensatory behavior. For example, one previous study found that the moral balance effect disappeared when participants recall a moral behavior performed by a friend (Conway & Peetz, 2012).

In psychological researches, one way to decrease individuals' responsible for their own choices was to perform external attribution. (Heider, 1958) defined attribution as the manners individuals use to explain the causes of events and behaviors. The reasons for behaving in a particular manner can be due to either self internal reason or a situational external reason (Kelley, 1967; Weiner, 1974). For example, if a student had a good performance in an exam, it can be attributed as the exam is too easy, which is external attribution, or the student worked hard to prepare for the exam, which is internal attribution. A positive relationship exists between internal attribution style and positive self-concept, and internally attributed individuals also have a more positive self-image of morality (Gadzella et al., 1985; Marsh, 1984). When an individual commits an unethical act and attributes it to an internal reason rather than an external one, the self-moral image is more likely to be threatened. By reclassifying and attributing individuals’ behaviors to external causes, people can avoid the risk of impairing their moral image (Mazar et al., 2008). (Harvey et al., 2017) found that the external and uncontrollable attribution can justify individuals’ behaviors and promote deviant behaviors in the workplace. (Forsyth et al., 1985) found that students paid attention to internal factors when they answered honestly, and emphasized the importance of external factors when they cheated.

As mentioned earlier, a self-moral image mediates people’s decisions about whether to act ethically or unethically (Mullen & Monin, 2016). However, if prior behavior is attributed to external factors, it may less likely affect one’s self-moral image (Clot et al., 2013); individuals therefore will be less likely to regulate their moral behaviors afterwards. As for altruistic lying, if attributing it to external reasons, it is hard for individuals to get a moral license and perform moral balance behaviors. Based on this, we further proposed:

-

Hypothesis 2: The effect of prior altruistic lies on subsequent selfish lies is smaller for externally than internally attributed individuals.

Contextual similarity and moral balance

Another factor that may influence the moral balance effect is the contextual similarity between prior and subsequent behaviors. Generally, two types of contextual similarities have been reported in previous studies: the previous and subsequent ethical choices are the same (e.g., helping others before and after); the two choices differ but are both related to personal ethical goals (e.g., buying green products before and choosing not to lie after,(Mullen & Monin, 2016). However, some scholars argued that the balance effect of behaviors in different fields cannot be replicated, (Urban et al., 2019) found that green consumption has no effect on subsequent dishonesty. Besides, some researchers used moral credential to explain the effect of moral balance, that is prior good behaviors change and reframe the meaning of subsequent behavior (Kong et al., 2020; Merritt et al., 2010). However, this moral credential can exists only when both the prior and subsequent behaviors are in the same domain (Effron & Monin, 2010). In another word, the context of behaviors need to be closely related to moral standards and similar to bring about moral balance. The participants are supposed to notice that the subsequent situation is in the same moral domain as the previous situation in order to compensate for prior unethical behavior through subsequent good behavior. Thus, the similarity between the tasks before and after may influence the moral balance effect.

Altruistic lying is contradictory in behavior and outcome: lying in behavior is considered unethical, while helping others in outcome is benevolent. Comparing the altruistic lie with the selfish lie reveals that the two are consistent only in behavior, but diametrically opposed in outcome. If participants focus on the behavior, they will notice the similarity between the prior altruistic lie task and the subsequent self-interested lie task (both are related to moral contexts), which could enhance the moral balance effect. However, if participants focus on the outcome, they will notice the differences between the two tasks (in the self-interested task, benefiting oneself has nothing to do with ethics), which could impair the moral balance effect. Based on this, we further hypothesized that:

-

Hypothesis 3: The effect of prior altruistic lies on subsequent selfish lies is greater for individuals who focus on behaviors than those who focus on outcomes.

Overview

In the present study, we tested the above hypotheses through four experiments. In Study 1, we measured participants’ voluntary choices on altruistic lies and explored whether these choices influence their subsequent selfish lies to examine Hypothesis 1. Specially, we introduced moral disengagement as a mediator to test the mechanism of the moral balance effect to examine Hypothesis 1b. In Studies 2–4, we manipulated participants’ prior altruistic lies to further test Hypothesis 1a. In addition, we also explored the moderated effects of attribution (internal vs. external) in Study 3 to examine Hypothesis 2, and the effect of contextual similarity (focus on behavior vs. focus on outcome) in Study 4 to examine Hypothesis 3.

Study 1

Method

Participants and design

Participants were 185 adults (117 females, 68 males) recruited from a professional data collection company (Credamo, https://www.credamo.com/). Their age ranged from 19 to 56 years (M = 28.49, SD = 6.44). We set a relative small R2 of model as 0.05 to calculate sample size. The sample exceeded the recommended size (n = 173) at 0.90 power (α = 0.05) by G*Power.

Measurements

Altruistic dishonesty

Altruistic dishonesty was measured by a dice-judgment task. In this task, participants were presented with ten pictures sequentially. There are two dices in each picture and participants should report whether those two dices have the same number. Participants were told that if participants report n times that the two dices are the same, the experimenter would donate n × 1 Chinese yuan to the foundation about rural children education. In fact, the numbers of two dices were always different in ten pictures, so the frequency of false report by participants was the indication of altruistic dishonesty.

Selfish dishonesty

Dishonest behaviors were measured by a Chinese character puzzle task. This task consists of 10 puzzles. In each puzzle, participants were given 3 or 4 components of Chinese character and asked to combine all these components into a correct recognized character. For each puzzle, participants only needed to report if they solve the puzzle or not, but did not need to report the specific character. Participants were told that their winning rate of an extra lottery reward would rise at a rate of 5 percent when each time they reported that having solved a puzzle. In fact, all 10 puzzles were unsolvable, so the number of solved puzzles that participants reported indicates the extent of dishonest behaviors.

Moral disengagement

Moral disengagement was measured by five items selected from the moral disengagement scale (Detert et al., 2008). The original scale has 25 items, including measurements of 8 different dimensions such as moral justification, euphemistic labeling, advantageous comparison, etc. We selected 5 items that are most related to our topic to save the experiment time and avoid participants fatigue. Specifically, we selected all items that measure moral justification, since they show a moral dilemma and are similar to altruistic lying, as we discussed in theory and hypotheses part before. These four items are " It is alright to fight to protect your friends", " It’s ok to steal to take care of your family’s needs ", " It’s ok to attack someone who threatens your family’s honor", " It is alright to lie to keep your friends out of trouble ". Plus, we selected one item on distortion of consequences, because it’s directly related to lying, which is " It is ok to tell small lies because they don’t really do any harm ". The Cronbach's α was 0.76 for all 5 items. Participants should rate the extent to which they agree with each item on a 7-points scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores represented higher moral disengagement.

Procedure

All participants received a link from the data collection company to take part in the study. Participants first reported their demographic information and then completed the altruistic dishonesty task, moral disengagement, and the selfish dishonesty task sequentially. After that, the study ended and participants were debriefed. It’s worth mentioning that even though moral disengagement was measured before dependent variable, since the items are all about prosocial lies, they are not supposed to have any guiding effect on the subsequent selfish lying behavior.

Results

Fifty-two of the 185 participants told at least one altruistic lie. There was no demographic difference between participants who lied and those who did not lie. Regarding gender, χ2 = 3.01, p = 0.083. Specifically, the altruistic dishonesty group comprised 14 male and 38 female participants, the non-altruistic honesty group comprised 54 male and 79 female participants. No significant difference in age was observed between the altruistic dishonesty group (M = 28.27, SD = 7.76) and the non-altruistic honesty group (M = 28.57, SD = 5.87), t(183) = 0.29, p = 0.775.

An independent-samples t test showed that participants who told altruistic lies exhibited more selfish dishonesty (M = 2.94, SD = 2.44) than those who did not tell any altruistic lie (M = 2.05, SD = 2.02), t(183) = 2.56, p = 0.011, d = 0.40. To further examine the mediation effect of moral disengagement in the relationship between altruistic dishonesty and selfish dishonesty, three regression analyses were conducted (Fig. 1). First, altruistic dishonesty significantly positively predicted moral disengagement, b = 0.05, SE = 0.02, t = 2.22, p = 0.028, \({\Delta R}^{2}\) = 0.02. Second, altruistic dishonesty significantly positively predicted selfish dishonesty, b = 0.11, SE = 0.05, t = 2.21, p = 0.029, \({\Delta R}^{2}\) = 0.02. Finally, when adding both altruistic dishonesty and moral disengagement into regression, the effect of moral disengagement was still significant, b = 0.40, SE = 0.16, t = 2.48, p = 0.014; but the effect of altruistic dishonesty was not significant, b = 0.09, SE = 0.05, t = 1.81, p = 0.073 (\({\Delta R}^{2}\) of the model was 0.05). A bootstrap analysis (10,000 bootstrapping samples) found that the indirect effect was 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% confidence intervals = (0.00, 0.05). These results suggest that the relationship between altruistic dishonesty and selfish dishonesty is completely mediated by moral disengagement (Baron & Kenny, 1986).

Discussion

The results of Study 1 were consistent with the moral balance theory, providing evidence for Hypothesis 1a and 1b. Besides, we found that moral disengagement had a mediating effect on the relationship between altruistic dishonesty and selfish dishonesty. People who told altruistic lies scored higher on moral disengagement and were more likely to justify their lying behavior. They believed that it is sometimes acceptable to lie if they have committed an act of kindness. Such beliefs motivated them to reward themselves for the act of self-interested lying. In contrast, participants who refused to help others by lying scored lower on moral disengagement, which suggests that they would justify their behaviors by believing that lying is unacceptable under any condition (even when it is done to help others). Therefore, their standards for lying would increase and they would tell less self-interested lies afterwards.

Since the results of Study 1 only showed a correlational relationship, we further manipulated prior altruistic lies to examine the causal relationship in Study 2.

Study 2

Method

Participants and design

Participants were 300 adults (174 females, 126 males) recruited from the same professional data collection company as in Study 1. Their age ranged from 18 to 55 years (M = 28.73, SD = 6.40). We set \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.05 which we found in Study 1 to calculate sample size. The sample exceeded the recommended size (n = 246) at 0.90 power (α = 0.05) by G*Power. The present study employed a one-factor between-participants design (Altruistic lie: Altruistic dishonesty vs. Non-altruistic honesty vs. Altruistic honesty).

Procedure

All participants received a link from the data collection company to take part in the study. The altruistic lie task was the same as in Study 1 except that participants were randomly assigned to one out of three conditions. Participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition were told that they should use any method (including false report) to maximize the total donation; while participants in the non-altruistic honesty and altruistic honesty condition were told that they should maximize the total donation on the premise of honest report. In all pictures presented to participants in the altruistic dishonesty and non-altruistic honesty conditions, the numbers of two dices were always different, so participants could tell lies to increase donations. However, for pictures presented to participants in the altruistic honesty condition, the numbers of two dices were always the same, so participants could increase donations without telling any lies. After that, participants completed the selfish dishonesty task as the same in Study 1. Then, the study ended and participants were debriefed.

Results

Seventeen participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition did not tell any altruistic lies, and two participants in the non-altruistic honesty condition told at least one altruistic lie. Hence, the data of these participants (n = 19) were excluded from further analyses. All participants in the altruistic honesty condition were always honest in the altruistic lie task.

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that the effect of altruistic lie was significant, F(2, 278) = 4.47, p = 0.012, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.03 (Fig. 2). Further analyses revealed that participants in the non-altruistic honesty condition told fewer selfish lies (M = 2.22, SD = 2.41) than those in the altruistic dishonesty condition (M = 3.35, SD = 2.86), p = 0.006, d = 0.43; and those in the altruistic honesty condition (M = 3.11, SD = 2.85), p = 0.022, d = 0.34. However, selfish dishonesty was not significantly different in the latter two conditions, p = 0.553, d = 0.08.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 re-affirmed Hypothesis 1a by examining the causal relationship between prior altruistic lies and subsequent self-interested lies. Participants in the altruistic lying group and the altruistic honesty group exhibited more self-interested lying behaviors than those in the non-altruistic honesty group because they helped others in terms of the outcome. According to the moral balance theory, after helping others (a moral act), participants believed they had earned the right to behave unethically with impunity, giving them a moral license to engage in the unethical behavior of self-interested lying. By contrast, participants in the non-altruistic honesty group placed a stricter restriction on lies and were less likely to tell selfish lies. Besides, there is no difference between altruistic dishonesty group and altruistic honesty group, which means after the participants conducted altruistic lying behavior, they concentrated on the benevolent consequence of helping others, and perceived the overall altruistic lying as moral.

Study 3

Method

Participants and design

Participants were 373 adults (222 females, 151 males) recruited from the same professional data collection company as in Study 1, and they received remuneration from the company for their participation. The age ranged from 18 to 60 years (M = 28.30, SD = 5.85). We set effect size \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.03 which we found in Study 2 to calculate sample size. The sample exceeded the recommended size (n = 342) at 0.90 power (α = 0.05) by G*Power. The present study employed a 2 (Altruistic lie: Altruistic dishonesty vs. Non-altruistic honesty) × 2 (Attribution: Internal vs. External) between-participants design.

Procedure

All participants received a link from the data collection company to take part in the study. The altruistic lie task was the same as in Study 1 except that participants were randomly assigned to either altruistic dishonesty or non-altruistic honesty conditions. This manipulation was the same as in Study 2. After completing the altruistic task, all participants were randomly assigned to either internal attribution or external attribution conditions. In the internal attribution condition, participants were told that "Although individuals' acts were influenced by external environment, the acts did be performed by themselves. So, any behaviors have internal reasons. Please write down at least three internal reasons that result in your behaviors in the prior task". However, in the external attribution condition, participants were told that "Although individuals' acts seem to be performed by themselves, the acts did be influenced by external environment. So, any behaviors have external reasons. Please write down at least three external reasons that result in your behaviors in the prior task". Then all participants completed a Chinese character puzzle task. After that, the study ended and participants were debriefed.

Results

Eighteen participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition did not tell any altruistic lies, and 10 participants in the non-altruistic honesty condition told at least one altruistic lie. So the data of these participants (n = 28) were excluded from further analyses.

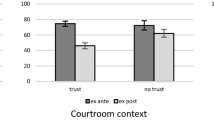

A 2 (altruistic lie: altruistic dishonesty vs. non-altruistic honesty) × 2 (Attribution: internal vs. external) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of altruistic lie, F(1, 341) = 15.60, p < 0.001, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.04, and a non-significant main effect of attribution, F(1, 341) = 0.41, p = 0.520, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) < 0.01. Finally, the interaction effect of altruistic lie and attribution was significant, F(1, 341) = 5.07, p = 0.025, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.02.

Further simple effect analyses showed that when attributing behaviors to internal reasons, participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition (M = 4.88, SD = 3.13) told more selfish lies than those in the non-altruistic honesty condition (M = 2.90, SD = 2.52), t(168) = 4.52, p < 0.001, d = 0.70 (Fig. 3). However, when attributing behaviors to external reasons, no significant difference was observed between participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition (M = 4.36, SD = 3.36) and the non-altruistic honesty condition (M = 3.82, SD = 2.81), t(173) = 1.16, p = 0.250, d = 0.14.

Discussion

Study 3 further demonstrated that the moral balance effect disappeared when participants attributed their prior behaviors to external reasons, which is in line with Hypothesis 2. This result suggests that attribution influences individuals’ perceptions of moral behaviors and their regulation of moral self-image. Internally attributed individuals believed they were responsible for the act and its outcome, and activated their moral self-perception before the altruistic lie task. Therefore, participants in the non-altruistic honesty group would remind themselves that they had just failed to help others, so they refrained from selfish dishonesty to recover a positive self-moral image.

In contrast, participants in the external attribution group believed that others were responsible for their dishonest or honest behaviors, so their moral consciousness was relatively less aroused and their prior dishonest or honest behaviors were less likely to affect their self-moral image (Khan & Dhar, 2006). As a result, the prior (non-)altruistic behaviors of participants in the external attribution group did not influence subsequent moral behaviors.

Study 4

Method

Participants and design

A total of 303 adults (161 females, 142 males) whose age ranged from 18 to 51 (M = 28.11, SD = 5.47) took part in this study. Participants recruited from the same professional data collection company as in Study 1, and they received remuneration from the company for their participation. We set \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.04 which we found in Study 3 to calculate sample size. The sample exceeded the recommended size (n = 255) at 0.90 power (α = 0.05) by G*Power. The present study employed a 2 (Altruistic lie: Altruistic dishonesty vs. Non-altruistic honesty) × 2 (Focus: Emphasizing behavior vs. Emphasizing outcome) between-participants design.

Procedure

All participants received a link from the data collection company to take part in the study. The task and manipulation of altruistic lie was the same as the Study 3. After completing the altruistic task, all participants were randomly assigned to either emphasizing behavior or emphasizing outcome conditions. Participants in the emphasizing behavior (or emphasizing outcome) condition were told that "All things done by individuals could be considered in term of both behavior and outcome. However, sometimes the behavior and outcome may be inconsistent: good behavior leads to bad outcome while bad behavior leads to good outcome. We found that most persons believed that the behavior is more important than outcome [the outcome is more important than behavior] in this dilemma. Please write down two specific situations that behavior is more important than outcome [outcome is more important than behavior] in real life". Then all participants completed a Chinese character puzzle task. After that, the study ended and participants were debriefed.

Results

Thirty-five participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition did not tell any altruistic lies, and six participants in the non-altruistic honesty condition told at least one altruistic lie. So those data (n = 41) were excluded from further analyses.

A 2 (Altruistic lie: Altruistic dishonesty vs. Non-altruistic honesty) × 2 (Focus: Emphasizing behavior vs. Emphasizing outcome) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of altruistic lie, F(1, 258) = 10.69, p = 0.001, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.04, and a non-significant main effect of focus, F(1, 258) = 1.12, p = 0.290, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) < 0.01. Finally, the interaction effect of altruistic lie and focus was significant, F(1, 258) = 5.64, p = 0.018, \({\eta }_{p}^{2}\) = 0.02.

As Fig. 4 shown, further simple effect analyses found that when emphasizing behavior, participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition (M = 5.41, SD = 3.24) told more selfish lies than those in the non-altruistic honesty condition (M = 3.28, SD = 2.56), t(129) = 4.11, p < 0.001, d = 0.73; however, when emphasizing outcome, there were no significant differences between participants in the altruistic dishonesty condition (M = 4.91, SD = 3.43) and the non-altruistic honesty condition (M = 4.57, SD = 2.96), t(129) = 0.60, p = 0.548, d = 0.11.

Discussion

Study 4 again demonstrated the moral balance effect and proved Hypothesis 3. The altruistic lie and subsequent self-interested lie tasks were only the same at the behavioral level. Participants who were guided to pay attention to behavior rather than outcome would be made aware of the similarity of the earlier and later task contexts, triggering the moral balance effect in the subsequent selfish lying task. However, individuals who focused on the outcome would concentrate on the difference between altruistic and self-interested lying: one was increasing other-interests and the other was increasing self-interests. When individuals found that the earlier and later tasks were completely different—the later task was not even related to the moral context—they were less likely to believe that these two behaviors can counteract each other. Therefore, in the emphasizing outcome condition, the moral balance effect would be less significant and could even disappear.

General discussion

All four studies found a consistent moral balance effect in which prior altruistic lying led to more self-interested lying, whereas individuals who previously rejected altruistic lying told fewer self-interested lies after. Moral disengagement plays a mediating role in this process. In addition, we also found that this moral balance effect was influenced by attribution and contextual similarity. If participants attributed prior moral behaviors to external reasons or focused on the differences between earlier and later situations, the moral balance effect disappeared.

Implications for theory and practice

In consistent with the construal level theory, this study found that the moral balance theory was supported when the psychological distance between prior and subsequent behaviors was close rather than far (Conway & Peetz, 2012; Eyal et al., 2009; Merritt & Monin, 2010). Previous studies of prior (im)moral behavior on subsequent (im)moral behavior have only dealt with participants’ own moral decisions (Gawronski & Strack, 2012; Mazar & Zhong, 2010; Monin & Miller, 2001; Young et al., 2012), and have been limited to selfish lies (Effron et al., 2015; Mazar et al., 2008; Pagliaro et al., 2016). However, none of them have examined whether altruistic lies follow the laws of moral consistency or moral balance. The paradox of altruistic lies is that, on the one hand, the act of lying is not promoted, while on the other, it brings about benevolent results. By including altruistic lies in the consideration of moral behavior continuity, the present study further explored how prior moral behavior influences future moral behavior and broadened the scope of discussion on moral balance. Moreover, our study also examined the potential boundary effect for moral balance theory. Specifically, Study 3 found that in order to obtain a moral balance, participants need to notice that they are responsible for the prior behaviors and related prior behaviors to self concept. This result was consistent with a previous study (Conway & Peetz, 2012) and suggested that self-image or self perception was a core mechanism underlying moral balance. And Study 4 found that the moral balance disappeared when exaggerating the differences between prior and subsequent behaviors. This result suggested that the moral balance would occur only when participants can related subsequent behaviors to prior ones.

In addition, if we concentrated on the non-altruistic honesty, this study also found another kind of moral consistency. For traditional moral consistency, scholars used to focus on behavioral consistency, such as prior and subsequent moral behaviors (Conway & Peetz, 2012; Joosten et al., 2014; Jordan et al., 2011; Mullen & Monin, 2016).However, the present study suggested a consistency of moral self concept. That is to say, individual who did not tell altruistic lies before would still refrain from telling self-interested lies after. The moral self is reflected in the statement: “I am an honest person, so I cannot lie no matter what the situation is.” When the individuals make decisions, they may not realize this underlying and deep mental dynamic directly, which requires them to focus on the value and moral goals behind the behavior. But this explanation probably has came into play without consciousness, such high level construal will lead to consistency in a micro psychological process. However, the present results still suggested that both moral balance and moral consistency are related to moral self. In order to maintain a positive moral self, participants in altruistic dishonesty condition reframed the meaning of lying by considering it is acceptable in some situations, whereas participants in non-altruistic honesty condition reframed the meaning of lying by emphasizing its inviolable across all situations. In total, the consistency of the moral self-concept and the balance of moral behavior are both reflected in this study, indicating that the two can coexist, but differ in their emphasis.

Practically, previous studies have mostly focused on the benefits of altruistic lying (DePaulo & Kashy, 1998; Levine & Schweitzer, 2014; Lupoli et al., 2017), but have often ignored the pitfalls it poses. This study proposed that although altruistic lies are considered a display of ethical behavior, individuals who lie in an altruistic lie task will later tell selfish lies with the effect of moral licensing. But if they refuse to tell altruistic lies, they are more likely to remain honest and engage in more ethical behaviors afterwards. Thus, altruistic lying is not as positive as one might always think as it can lead to moral decline.

Limitations and future directions

In reality, many altruistic lies are more complex and have features that are not represented in our study, in which we set up lies that led to monetary gain. However, in real life, many lies, especially altruistic lies, are mixed with emotions (e.g., people lying to protect the feelings of others, (DePaulo, 1992). A difference also exists between helping others to avoid losses and helping others to gain something, with the former being perceived as more psychologically powerful (Kahneman & Tversky, 2013). Thus, there may be limitations to using only the experimental task of monetary gain. Future research could expand this scenario to examine if the moral balance effect remains after altruistic lying.

In addition, previous research has found that temporal factors also influence moral behavior, with participants recalling moral behaviors that occurred a long time ago as being different from those that occurred more recently in terms of future decisions (Fishbach et al., 2006). The results of this study may differ if there is a time lag between altruistic lies and self-interested lies.

Furthermore, the participants of this study are the communicators of lies; future research can focus on the behavior of the recipient of the lie. Previous research has found that altruistic lies from others make the target more likely to lie later on (Tyler et al., 2006). Thus, one could focus on whether others’ altruistic lies have an effect on the target’s subsequent self-interested lying behavior. Moreover, whether others’ selfish lying behavior interferes with the target’s subsequent altruistic lying decisions can also be examined in future research.

Data availability

The data can be download via https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/WD8Y9.

References

Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423–1440. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1423

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral Disengagement in the Perpetration of Inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

Baumeister, R. F. (1987). How the self became a problem: A psychological review of historical research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 163. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.163

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (pp. 1–62). New York: Academic Press.

Blasi, A. (1980). Bridging moral cognition and moral action: A critical review of the literature. Psychological Bulletin, 88(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.1.1

Brañas-Garza, P., Bucheli, M., Espinosa, M. P., & García-Muñoz, T. (2013). Moral cleansing and moral licenses: Experimental evidence. Economics & Philosophy, 29(2), 199–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266267113000199

Cheung, H., Chan, Y., & Tsui, W. C. G. (2016). Effect of lie labelling on children’s evaluation of selfish, polite, and altruistic lies. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12132

Clot, S., Grolleau, G., & Ibanez, L. (2013). Self-licensing and financial rewards: is morality for sale? Economics Bulletin, 33, 2298–2306. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01189989. Accessed 7 May 2022.

Conway, P., & Peetz, J. (2012). When does feeling moral actually make you a better person? Conceptual abstraction moderates whether past moral deeds motivate consistency or compensatory behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(7), 907–919. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212442394

Cornelissen, G., Pandelaere, M., Warlop, L., & Dewitte, S. (2008). Positive cueing: Promoting sustainable consumer behavior by cueing common environmental behaviors as environmental. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 25(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.944391

DePaulo, B. M. (1992). Nonverbal behavior and self-presentation. Psychology Bulletin, 111(2), 203–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.203

DePaulo, B. M., & Bell, K. L. (1996). Truth and investment: Lies are told to those who care. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(4), 703. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.4.703

DePaulo, B. M., & Kashy, D. A. (1998). Everyday lies in close and casual relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.63

Detert, J. R., Trevino, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengagement in ethical decision making: A study of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(2), 374–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.374

Dunbar, N. E., Gangi, K., Coveleski, S., Adams, A., Bernhold, Q., & Giles, H. (2016). When is it acceptable to lie? Interpersonal and intergroup perspectives on deception. Communication Studies, 67(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2016.1146911

Effron, D. A., Bryan, C. J., & Murnighan, J. K. (2015). Cheating at the end to avoid regret. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(3), 395. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000026

Effron, D. A., Cameron, J. S., & Monin, B. (2009). Endorsing Obama licenses favoring whites. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 590–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.001

Effron, D. A., & Monin, B. (2010). Letting people off the hook: When do good deeds excuse transgressions? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(12), 1618–1634. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210385922

Ennis, E., Vrij, A., & Chance, C. (2008). Individual differences and lying in everyday life. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507086808

Erat, S., & Gneezy, U. (2012). White lies. Management Science, 58(4), 723–733. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1449

Eyal, T., Sagristano, M. D., Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Chaiken, S. (2009). When values matter: Expressing values in behavioral intentions for the near vs. distant future. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.07.023

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Fishbach, A., Dhar, R., & Zhang, Y. (2006). Subgoals as substitutes or complements: The role of goal accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(2), 232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.232

Forsyth, D. R., Pope, W. R., & McMillan, J. H. (1985). Students’ reactions after cheating: An attributional analysis. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 10(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-476x(85)90007-4

Gadzella, B. M., Williamson, J. D., & Ginther, D. W. (1985). Correlations of self-concept with locus of control and academic performance. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 61(2), 639–645. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1985.61.2.639

Gawronski, B., & Strack, F. (Eds.). (2012). Cognitive consistency: A fundamental principle in social cognition. New York: Guilford Press.

Gino, F., & Ariely, D. (2015). Dishonesty explained: What leads moral people to act immorally. In A. G. Miller (Ed.), The Social Psychology of Good and Evil (pp. 322–342). New York: Guilford Press.

Gollwitzer, M., & Melzer, A. (2012). Macbeth and the joystick: Evidence for moral cleansing after playing a violent video game. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(6), 1356–1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.07.001

Harvey, P., Martinko, M. J., & Borkowski, N. (2017). Justifying deviant behavior: The role of attributions and moral emotions. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(4), 779–795. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3046-5

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.2307/2572978

Henderson, M. D., & Burgoon, E. M. (2014). Why the door-in-the-face technique can sometimes backfire: A construal-level account. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(4), 475–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/e514472015-498

Iezzoni, L. I., Rao, S. R., DesRoches, C. M., Vogeli, C., & Campbell, E. G. (2012). Survey shows that at least some physicians are not always open or honest with patients. Health Affairs, 31(2), 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.1137

Iniguez, G., Govezensky, T., Dunbar, R., Kaski, K., & Barrio, R. A. (2014). Effects of deception in social networks. Proceedings of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences, 281(1790), 20141195. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1195

Jennings, P. L., Mitchell, M. S., & Hannah, S. T. (2015). The moral self: A review and integration of the literature. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(S1), S104–S168. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1919

Joosten, A., Van Dijke, M., Van Hiel, A., & De Cremer, D. (2014). Feel good, do-good!? On consistency and compensation in moral self-regulation. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1794-z

Jordan, J., Mullen, E., & Murnighan, J. K. (2011). Striving for the moral self: The effects of recalling past moral actions on future moral behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(5), 701–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211400208

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (2013). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. In L. C. MacLean, & W. T. Ziemba (Eds.), Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I (pp. 99–127). Hackensack: World Scientific Publishing.

Kelley, H. H. (1967). Attribution theory in social psychology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (Vol. 15, pp. 192–238). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Khan, U., & Dhar, R. (2006). Licensing effect in consumer choice. Journal of Marketing Research, 43(2), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.43.2.259

Kong, M., Xin, J., Xu, W., Li, H., & Xu, D. (2020). The moral licensing effect between work effort and unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating influence of Confucian value. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-020-09736-8

Kraut, R. E. (1973). Effects of social labeling on giving to charity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(6), 551–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(73)90037-1

Lasarov, W., & Hoffmann, S. (2020). Social moral licensing. Journal of Business Ethics, 165(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-4083-z

Levine, E., & Munguia Gomez, D. (2021). “I’m just being honest.” When and why honesty enables help versus harm. Journal of personality and social psychology, 120(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000242

Levine, E. E., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2014). Are liars ethical? On the tension between benevolence and honesty. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 53, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.03.005

Levine, E. E., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2015). Prosocial lies: When deception breeds trust. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 126, 88–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.10.007

Lupoli, M. J., Jampol, L., & Oveis, C. (2017). Lying because we care: Compassion increases prosocial lying. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146(7), 1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000315

Marsh, H. W. (1984). Relations among dimensions of self-attribution, dimensions of self-concept, and academic achievements. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(6), 1291. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.6.1291

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.6.633

Mazar, N., & Zhong, C.-B. (2010). Do green products make us better people? Psychological Science, 21(4), 494–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610363538

Merritt, A., & Monin, B. (2010). Coming clean about (not) being green: Value assertions increase admissions of environmentally-unfriendly behavior [Poster]. The annual meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Las Vegas, NV.

Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., & Monin, B. (2010). Moral self-licensing: When being good frees us to be bad. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00263.x

Miller, D. T., & Effron, D. A. (2010). Psychological license: When it is needed and how it functions. In M. P. Zanna & J. M. Olson (Eds.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 43, pp. 115–155). Academic Press.

Monin, B., & Jordan, A. H. (2009). The dynamic moral self: A social psychological perspective. Personality, Identity, and Character: Explorations in Moral Psychology, 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511627125.016

Monin, B., & Miller, D. T. (2001). Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.33

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., KlebeTreviño, L., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and unethical organizational behavior. Personnel Psychology, 65(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01237.x

Mullen, E., & Monin, B. (2016). Consistency Versus Licensing Effects of Past Moral Behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 363–385. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115120

Nelson, L. D., & Norton, M. I. (2005). From student to superhero: Situational primes shape future helping. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(4), 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2004.08.003

Paciello, M., Fida, R., Cerniglia, L., Tramontano, C., & Cole, E. (2013). High cost helping scenario: The role of empathy, prosocial reasoning and moral disengagement on helping behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.004

Pagliaro, S., Ellemers, N., Barreto, M., & Di Cesare, C. (2016). Once dishonest, always dishonest? The impact of perceived pervasiveness of moral evaluations of the self on motivation to restore a moral reputation. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 586. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00586

Palmieri, J. J., & Stern, T. A. (2009). Lies in the doctor-patient relationship. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 11(4), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.09r00780

Patrick, R. B., Bodine, A. J., Gibbs, J. C., & Basinger, K. S. (2018). What accounts for prosocial behavior? Roles of moral identity, moral judgment, and self-efficacy beliefs. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 179(5), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2018.1491472

Sachdeva, S., Iliev, R., & Medin, D. L. (2009). Sinning saints and saintly sinners: The paradox of moral self-regulation. Psychological Science, 20(4), 523–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02326.x

Schei, T. S., Sheikh, S., & Schnall, S. (2019). Atoning past indulgences: Oral consumption and moral compensation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2103. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02103

Steele, C. M. (1988). The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 21, pp. 261–302). Academic Press.

Stone, J., & Cooper, J. (2001). A self-standards model of cognitive dissonance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37(3), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2000.1446

Talwar, V., Murphy, S. M., & Lee, K. (2007). White lie-telling in children for politeness purposes. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025406073530

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018963

Tyler, J. M., Feldman, R. S., & Reichert, A. (2006). The price of deceptive behavior: Disliking and lying to people who lie to us. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(1), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.02.003

Urban, J., Bahník, Š, & Kohlová, M. B. (2019). Green consumption does not make people cheat: Three attempts to replicate moral licensing effect due to pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.01.011

Vallacher, R. R., & Solodky, M. (1979). Objective self-awareness, standards of evaluation, and moral behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 15(3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(79)90036-2

Vanberg, C. (2008). Why do people keep their promises? An experimental test of two explanations 1. Econometrica, 76(6), 1467–1480. https://doi.org/10.3982/ecta7673

Weiner, B. (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. Morristown, New Jersey: General Learning Press.

Yam, K. C., Klotz, A. C., He, W., & Reynolds, S. J. (2017). From good soldiers to psychologically entitled: Examining when and why citizenship behavior leads to deviance. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0234

Young, L., Chakroff, A., & Tom, J. (2012). Doing good leads to more good: The reinforcing power of a moral self-concept. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 3(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-012-0111-6

Zhong, C. B., & Liljenquist, K. (2006). Washing away your sins: Threatened morality and physical cleansing. Science, 313(5792), 1451–1452. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1130726

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Humanity and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (20YJC190001); Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2019A1515110193); Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee Stability Support Program (20200813121341001) ; Guangdong 13th-five Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (GD20CXL06). This study was not a preregistered.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study concept and design, Testing and data collection. Cai drafted the manuscript, and Wu provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants adheres to ethical guidelines specified in the APA Code of Conduct as well as the authors’ national ethics guidelines. The study design was approved by the IRB of Shenzhen University.

Informed consent

All participants were provided informed consent before the formal study.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, S., Wu, S. Dark side of white lies: How altruistic lying impacts subsequent self-interested lying. Curr Psychol 43, 5090–5103 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04678-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04678-y