Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between perceived social support and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) behavior. 3539 adolescents were recruited to complete the Multidimensional Social Support Scale, Hope Scale, Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents and NSSI Scale. The results showed that perceived social support significantly negatively predicted adolescent NSSI behavior, and resilience played a mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior. In addition, perceived social support could also promote the levels of adolescent resilience through hope, thereby further reducing the frequency of adolescent NSSI behavior. The results suggest that the intervention of adolescent NSSI can start from providing a safe and effective external environment.

Highlights

-

1.

This study revealed the internal mechanism of NSSI from the perspective of “environment-psychological ability-behavior” for the first time. The results showed that resilience played a mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior.

-

2.

In this study, we found that hope and resilience, which are both positive psychological traits, had different influence paths on adolescent NSSI behavior. Hope needed to affect NSSI behavior by promoting resilience, but resilience could directly affect NSSI behavior. This suggested us that there may be a certain type of positive psychological quality that could protect adolescents from NSSI.

-

3.

From the perspective of positive development, this study explored the protective factors and their internal mechanisms that influence NSSI. On the one hand, it enriched the research on protective factors of NSSI. On the other hand, it provided a new idea for the intervention of adolescents’ NSSI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), defined as the behavior that an individual intentionally and repeatedly changes or harms his or her own body without explicit suicidal intention, and such behavior is not accepted by the society and is either non-lethal or less lethal (Gratz, 2001). Adolescents are at high risk of NSSI. Studies have shown that 22.1% of adolescents had engaged in non-suicidal NSSI in their lifetime, and 19.5% of them had done so in the past 12 months (Lim et al., 2019). Current data shows that the incidence of NSSI behavior is on the rise globally and has become a major public health problem in many countries (Thippaiah et al., 2020; Mummé et al., 2017), which has attracted wide attention from all walks of life (Brown & Plener, 2017). In addition to the physical harm caused by the behavior itself, recent studies have shown that the experience of NSSI behavior may also increase the risk of future suicidal ideation and behavior in adolescents (Fox et al., 2015; Kiekens et al., 2018). At the same time, a large number of studies have shown that NSSI behavior is significantly correlated with various psychological disorders such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders and personality disorders (Schatten et al., 2015). In addition, some researchers have confirmed that NSSI behavior has a significant “contagious” effect among adolescents (Brown & Plener, 2017; Syed et al., 2020), all of which pose a serious threat to adolescent socialization and future mental health (Kruzan & Whitlock, 2019). In view of the high incidence of NSSI among adolescents and the negative influence it brings to adolescents, it is necessary to conduct in-depth research on the influential factors and mechanisms of NSSI.

Previous studies have found that negative situations or experiences such as social exclusion, peer rejection or bullying and childhood abuse could positively predict adolescents NSSI (Wang et al., 2020; Esposito et al., 2019; Martin et al., 2016). However, these studies mainly focused on the correlation between negative situational factors and NSSI, and rarely explored the relationship between positive factors and NSSI and its internal mechanism. In other words, most of the existing researches focuses on the risk factors of NSSI, largely ignoring protective factors, such as a safe and effective external environment or positive personal traits, etc. These positive factors can buffer the adverse effects of negative factors, which is of great significance for the study of adolescents’ NSSI behavior. In addition, Positive Youth Development (PYD) pointed out that adolescents themselves have great potential and could develop in a positive direction, and the positive development of young people was benefited from the support of a good external environment (Benson et al., 2006). Therefore, this study focuses more on exploring the related factors and mechanisms of NSSI among adolescents from a positive perspective. As individuals enter adolescence, the main people they spend time with are family members, friends, and significant others (Hombrados-Mendieta et al., 2012), and adolescents begin to confide in and seek support from some of them (Narayanan & Onn, 2016). In relevant studies, social support was regarded as a buffer factor that can effectively reduce the adverse effects of negative emotional behaviors. It can increase the psychological motivation of individuals, and is beneficial to their emotional, cognitive and psychological status, thus promoting their physical and mental health. (Gülaçtı, 2010). The higher the level of perceived social support, the lower the possibility of NSSI among adolescents (Yamada et al., 2014). In view of this, from the perspective of promoting the positive development of adolescents, we will pay more attention to the relationship and underlying mechanisms between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI.

Perceived social support and NSSI

Social support includes actual social support and perceived social support. Compared with actual social support, perceived social support has a stronger impact on mental health than actual social support (Hefner & Eisenberg, 2009; Zhang et al., 2018). Perceived social support means an individual’s perceived respect, care and help from surrounding social relationships (such as families, friends, significant others, etc.) (Alloway & Bebbington, 1987). According to the main-effect model of social support, perceived social support has a general positive effect (Malecki & Demaray, 2003). For example, perceived social support could help alleviate individual psychological stress response, improve social adaptability and maintain individual mental health (Ren et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2020). Individuals are easy to fall into negative emotions when face stressful situations, and NSSI is often used by them to relieve negative emotions (Nock & Prinstein, 2004; Klonsky, 2007), which is clearly a negative coping way to solve a problem. While peiceived social support could help alleviate the negative effects of various negative stimuli and avoid negative emotions (Etzion, 1984; Fried & Tiegs, 1993), to a certain extent, this may be helpful to reducing the frequency of NSSI among adolescents. In addition, as some scholars have pointed out, the more social support an individual perceived, the less likely he is to adopt a negative coping style such as NSSI when faced with stressful situations or negative emotions (Geng et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2021). Nemati et al. (2020) also confirmed that low level of social perception would increase the incidence of NSSI. To sum up, perceived social support may have a positive impact on adolescent NSSI. However, in order to better carry out the prevention and intervention of adolescent NSSI behavior, it is necessary not only to explore the correlation between variables, but also to study the mechanism.

The mediating role of hope

While social support can directly affect NSSI, it may also indirectly affect NSSI behavior through individual internal factors. With the development of positive psychology, hope has attracted much attention from researchers as one of the important psychological qualities. Besides, among the many endogenous factors, hope is one that may have a positive effect on emotion. Hope is defined as a cognitive ensemble consisting of (1) agency (goal-directed decisions) and (2) pathways (planning of ways to achieve goals) (Snyder et al., 1991). Scholars regard hope as a future-oriented force and a motivational component in the cognitive process (Pacico et al., 2013), and believe that hope is a psychological activity process and cognitive state (Wu, 2011). According to the Environmental Function Model (Environmental Function Model), cognitive belief is another important factor affecting NSSI behavior, therefore, to a certain extent, hope may affect adolescent NSSI behavior. In addition, empirical studies have found that hope could cultivate and develop an individual’s positive psychology and improve an individual’s mental health (Rock et al., 2014). Another study also pointed that hope could significantly predict positive emotion (Ciarrochi et al., 2015), and positive emotion can help reduce the occurrence of NSSI behaviors in return (Hasking et al., 2017). Based on the above discussion, we can reasonably speculate that hope may have a positive effect on slowing down or inhibiting the adolescent NSSI behavior.

The construction of hope is closely related to the perceived social support. According to Snyder’s hope theory, perceived social support is an important factor affecting hope (Kemer & Atik, 2012), for example, perceived support from parents and friends is good for the establishment and development of hope (Morley & Kohrt, 2013; Simmons et al., 2009). In addition, previous study found that there was a significant positive correlation between the perceived social support and hope (Li & Yin, 2015), and the more social support an individual perceived, the higher the level of hope (Wang et al., 2006). It can be seen that perceived social support has a positive effect on the improvement of hope.

The mediating role of resilience

The individual’s psychological ability has also attracted the attention of many researchers as an internal path that affects individual behavior. Some researchers have found that social support, as a situational factor, could not only directly affect individual behavior, but also indirectly through individual psychological ability (such as resilience) (Sun et al., 2013). This suggests that we may be able to explain the internal mechanism of NSSI behavior from the perspective of “environment-psychological ability-behavior”. Resilience refers to the ability of an individual to recover and maintain good adaptive system function after experiencing a stressing event (Masten, 2014). According to PYD, the adolescents’ own potential could promote the positive development of adolescents (Chang et al., 2020), and resilience, as a positive psychological potential, may be beneficial to reduce the occurrence of NSSI behaviors, thus allowing adolescents to return to a positive developmental track. Further, empirical studies have found that the main purpose of NSSI behavior is to release negative emotion in order to maintain the dynamic balance of the psychological level (Hasking et al., 2017). While resilience can make use of all available protective resources when facing stressing situations to restore the balance of individual psychological level and achieve good adaptation (Cha & Lee, 2018), so as to avoid adolescent NSSI. Moreover, Garisch and Wilson (2015) also found that lower levels of resilience were associated with NSSI behaviors among adolescents, and that resilience may be a useful target for further research and clinical interventions for NSSI in adults (Colpitts & Gahagan, 2016). Based on the above theory and literature, we can see that resilience have a certain impact on adolescent NSSI behavior.

The development of resilience in adolescents may benefit from perceived social support. As individuals enter adolescence, they begin to be more willing to disclose personal matters to their friends or significant others than to family members (Baharudin & Zulkefly, 2009). A person may think of receiving support from family, friends, or significant others, and that this perceived social support enables the individual to cope with hardships and recover from adversity (Mattanah et al., 2010). Studies have found that there is an intrinsic link between perceived social support and resilience, and great perceived social support contributed to the development of individual resilience (Ozbay et al., 2008), and more importantly, the more social support individual perceived, the higher levels of resilience will be (Southwick et al., 2016; Stewart & Yuen, 2011). Narayanan and Onn (2016) also showed that perceived social support significantly positively predicted adolescents’ resilience. These studies suggest that individuals in a good social support environment can develop higher levels of resilience.

The mediating role of hope and resilience

There is also a link between hope and resilience. Ong et al. (2006) believed that hope may be one of the important sources of psychological resilience. Not only could hope reduce negative emotion and protect individuals, but also help to promote social adaptation of individuals and recover from stress. Empirical studies have confirmed that there was a significant positive correlation between hope and resilience, the higher the level of hope, the higher the level of resilience (Kirmani et al., 2015; Mullin, 2019). Besides, previous studies also found that hope can significantly positively predict resilience (Satici, 2016) and hope could be an important factor to promote resilience (Granek et al., 2013). In addition, Condly’s review of psychological research on children and resilience showed that resilient adults typically attributed their resilience as children to hope (Condly, 2006). Therefore, based on the previous discussion, it is reasonable to speculate that perceived social support may also affect psychological resilience through hope, thereby further affecting adolescent NSSI behavior.

The current study

Risk factors for NSSI have been relatively well studied. However, it is not enough to focus on risk factors alone for a comprehensive understanding of NSSI, the protective factors of NSSI such as safety environment and positive traits also should be paid attention to. Therefore, this study focused on exploring the impact of protective factors on adolescent NSSI behavior. According to the view of PYD (Benson et al., 2006) and the main-effect model of social support (Malecki & Demaray, 2003), a safe and effective external environment can promote the healthy development of adolescents. Based on above theory, this study investigated the impact of perceived social support on adolescent NSSI behavior and its internal mechanism. The study controlled for the effect of age and gender (Bresin & Schoenleber, 2015; Huang et al., 2021). Based on the above discussion, we proposed some hypothesis as follows:

-

Hypothesis 1: Perceived social support can negatively predict adolescent NSSI behavior.

-

Hypothesis 2: Hope may play a mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior.

-

Hypothesis 3: Resilience may play a mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior.

-

Hypothesis 4: Perceived social support may predict adolescent NSSI behavior through the sequential mediating effect of hope and resilience.

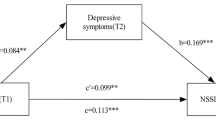

The hypothetical model as shown in Fig. 1.

Method

Participants

A total of 3629 adolescents were invited to participate in this study. Except for large-scale blanks and regular responses, etc., the final effective questionnaires used for data analysis totaled 3539, meaning that the effective recollection rate was 97.52%. 2247 (63.5%) males and 1292 females (36.5%) were included in the final sample, with the average age in the first experiment 16.22 ± 0.99 years old.

Procedure

The university’s research ethics committee approved this study. We obtained the consent from students, parents and teachers before data collection. All participants completed the questionnaire collectively in the classroom under the guidance of professionally trained postgraduate and homeroom teachers. The questionnaire is completed online via smartphone and the results are confidential. After collecting the questionnaires, all students received individual brochures with contact details of various help-lines, as safety precautions. Besides, we also distributed some small gifts to them in return.

Measures

Perceived social support

Perceived social support was measured through the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) developed by Zimet et al. (1988) and revised by Zhao and Li (2017). This scale includes twelve items measuring the perceived social support from families, friends and others important. Participants rated each item (e.g., “I can talk about my problems with my friends”) on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagrees) to 7 (completely agrees). The higher the score, the higher level of the perceived social support. The good reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the scale has been confirmed among Chinese samples (Chen et al., 2020). The Cronbach’s α coefficients for families support, friends support and others important support were 0.934, 0.939, and 0.923, respectively. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the total scale was 0.965.

Non-suicidal self-injury

Seven NSSI behaviors, such as self-cutting, burning, scratching skin, inserting objects to the nail or skin, biting, punching, and banging the head or other parts of the body against the wall, were assessed in the current study. All seven NSSI behaviors were selected from the Deliberate Self-harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001), and these seven NSSI behaviors were most common in adolescents (Nock & Favazza, 2009). Participants were asked to rate each item (e.g., “I scratched my skin”) on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = three to five times, to 4 = six times or more. This scale has demonstrated sufficient concurrent and overtime validity among Chinese adolescents (Jiang et al., 2020). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the scale was 0.930.

Hope

Hope was assessed using a scale developed by Snyder (1996), which concluded two dimensions of hope: pathways and agency. Participants were asked to rate each item (e.g., “There are many solutions to my present problem”) on an 8-point Likert scale from 1 (incompletely agreed) to 8 (completely agreed). The good reliability and validity of the scale has been confirmed among Chinese samples (Li et al., 2022). Higher scores indicated higher levels of hope. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for pathways dimension and agency dimension were 0.848 and 0.772, respectively. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the total scale was 0.893.

Resilience

We used the Resilience Scale for Chinese Adolescents (Hu & Gan, 2008) to measure the adolescents’ resilience. The scale includes five sub-dimensions: goal-focused (e.g., my life has a clear goal), emotional control (e.g., failure always makes me feel discouraged), positive cognition (e.g., I think adversity has a positive effect on people), family support (e.g., my parents respect my opinion) and interpersonal assistance (e.g., I will talk to others when I have difficulties). Since the questions of the support force dimension and the perceived social support scale overlapped, this study selected only one of the questions related to the human force dimension. The good reliability and validity of the scale has been confirmed in previous study (Fan et al., 2018). Participants rated each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate greater resiliency. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for goal-focused, emotional control and positive cognition were 0.865, 0.718, and 0.858, respectively. The Cronbach’s α coefficients for the total scale was 0.741.

Data analyses

SPSS 22.0 was used for statistical analysis, and descriptive analysis and Pearson correlation were used to test the key variables. Structural equation models were applied to test hypothesis models. Missing data were handled with expectation maximization (EM) (Gold & Bentler, 2000). With gender and age controlled, we analyzed the total effect of perceived social support on NSSI.

Next, we assessed the mediating roles of hope and resilience between perceived social support and NSSI. The Model Indirect Command Model was adopted to assess the statistical significance of the indirect effects, i.e., the effects of perceived social support on NSSI via (a) the hope path and (b) the resilience. To examine the mediation effects and bias-corrected percentile confidence intervals (CIs), the bootstrapping test was used, employing 1000 samples (MacKinnon, 2008). A confidence interval containing 0 indicates that the relevant parameter is not significant.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and correlations for all study variables. All the variables revealed significant associations with each other. As we can see, perceived social support, hope and resilience were positively associated with each other, while NSSI was negatively correlated with perceived social support, hope and resilience. These results provided a solid foundation for structural equation model analysis.

Measurement model

By controlling age and gender, we examined the direct effect of perceived social support on NSSI. The model fits well as a whole [χ2/df = 0, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, SRMR = 0, RMSEA = 0]. The results showed that perceived social support significantly negatively predicted NSSI (β = −0.121, SE = 0.019, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.158, −0.084]). That was, the higher the levels of perceived social support, the less NSSI.

Structural model

Next, we assessed the mediating roles of hope and resilience between perceived social support and NSSI, controlling for age and gender. As shown in Fig. 2, the model revealed an acceptable fit to data: χ2/df = 7.879, CFI = 0.975, TLI = 0.940, SRMR = 0.019, RMSEA = 0.044. Perceived social support significantly positively predicted hope (β = 0.403, SE = 0.017, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.368, 0.435]) and resilience (β = 0.232, SE = 0.019, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.195, 0.269]), while significantly negatively predicted NSSI (β = −0.090, SE = 0.023, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.136, −0.047]). And hope significantly positively predicted resilience (β = 0.186, SE = 0.019, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.149, 0.224]), while resilience significantly negatively predicted NSSI (β = −0.110, SE = 0.017, p < 0.001, 95% CI [−0.143, −0.077]). In addition, as can be seen from Table 2, for perceived social support, resilience probably mediated the link between it and NSSI. There was an acceptable fit for the pathways of perceived social support—resilience—NSSI (indirect effect = −0.026, 95% CI = [−0.034, −0.018]). For the serial mediation, hope and resilience played a serial mediating role between perceived social support and NSSI (indirect effect = −0.008, 95% CI = [−0.012, −0.006]).

Discussion

The perceived social support and NSSI

This study examined both the effects and mechanisms of perceived social support on adolescents’ NSSI within the framework of PYD and the main effect of social support. It was found that perceived social support could reduce adolescent NSSI behavior. In addition, perceived social support can reduce NSSI behavior by promoting resilience in adolescents. Last but not least, hope and resilience played a sequentially mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior. The findings of this study will help us to further understand how perceived social support affects adolescents’ NSSI behavior, and also inspire us to prevent NSSI by improving adolescents’ hope level and psychological resilience.

Perceived social support could significantly negatively predict adolescents’ NSSI behavior, which is consistent with previous research results (Park & Crocker, 2008). When individuals perceived more social support, they are more likely to have more positive coping styles, so it is possible to reduce the occurrence of NSSI. Besides, social support means that the individual is loved, cared for, and respected. When adolescents perceived more social support increases, the feelings of exclusion and rejection would be less, and the individual was placed in a relatively safe environment (Turner et al., 2016). At this time, the more social support an individual perceived, the more immediate planning and positive reappraisal were able to moderate emotional responses (Pejičić et al., 2018), which contributed to the reduction of negative emotion and thus reduced NSSI behaviors possibility of occurrence. This suggests that a safe and effective external environment may be beneficial to the reduction of adolescent NSSI behavior.

The mediating role of hope and resilience

After controlling for demographic factors such as gender and age, we found that resilience played a mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior, supporting Hypothesis 3. It was found that perceived social support positively predicts mental resilience, which is consistent with previous research result (Kalaitzaki et al., 2021). The ability of resilience has been shown to be determined by environmental factors (Ungar et al., 2008), and social support (e.g., from family members) that individuals perceived at an early age could promote positive cognitive, social, and emotional development, including self-regulation skills and resilience (Masten & Gewirtz, 2006). When adolescents perceived social support from others, their self-confidence and self-esteem were improved to a certain extent, and they were able to interpret certain situations positively, and made use of available resources to solve problems and restore resilience (Pejičić et al., 2018). Resilience could negatively predict NSSI behavior in adolescents, which is also consistent with previous study (Hilt et al., 2008). Because adolescents with high resilience could interpret events more positively when faced with stressing situations (Greenberg, 2006), they were unlikely to adopt non-adaptive coping methods such as NSSI behaviors.

Furthermore, this study found that perceived social support can significantly positively predict hope, which was consistent with previous study (Zhang et al., 2010). Social networks provided individuals with positive experiences and relatively stable social rewards (Fried & Tiegs, 1993), and perceived social support could improve a person’s overall level of happiness and promote the establishment of positive qualities, including hope (Xiang et al., 2020). For example, perceived support from friends or teachers could help individuals overcome obstacles and establish goal-directed strategies, which can affect an individual’s level of hope (Parker et al., 2015). However, hope was not significantly predictive of NSSI. A possible explanation is that, as Snyder argued, hope was an individual’s cognitive motivation for the pursuit of one’s own goals, with a future orientation that provided the basis for goal setting and planning (Snyder et al., 1997). The powerful psychological driving force and goal orientation brought by hope urged people to move forward in the direction of anticipation or desire (Snyder, 2000). This cognitive belief is the driving type, which may not directly affect NSSI, but can indirectly affect NSSI through other factors. For example, a study about hope and NSSI found that the effect of hope on NSSI was realized through the mediation of self-compassion (Jiang et al., 2021). Therefore, it is particularly important to explore the sequential mediation of hope promoting resilience.

A sequential mediation

It was worth noting that although the mediating effect of hope on the perceived social support and NSSI was not significant, hope could indirectly affect NSSI by affect individual’s resilience, that is, hope and resilience played a sequential mediating role between the perceived social support and NSSI. As previous studies have pointed out, the more social support an individual perceived, the higher their levels of hope (Yucens et al., 2019). People full of hope typically judged situations in a positive way and evaluated stressing situations as challenging rather than threatening (Rubin, 2008), which allowed them to better recover from stressing situations. Therefore, adolescents with high levels of hope have strong resilience. Furthermore, Resilience can alleviate the negative impact of emotional distress on adolescent mental health (Min et al., 2013). Adolescents with high mental resilience may have higher flexibility and emotional regulation ability, which could help them avoid negative outcomes (such as NSSI) (Waugh et al., 2011), and this was consistent with our research results. The sequential mediation suggests that the intervention of adolescents NSSI could start from providing a safe and effective external environment. In a good environment, adolescents’ own positive psychological traits could be well developed, so as to avoid NSSI behavior and other mental health.

Limitations and implications

This study has some limitations. First, the study was carried out on the basis of cross-sectional data, so we still need to be cautious in causal inference. In the future, we can continue to carry out longitudinal investigation on the subjects in order to obtain more comprehensive data, so as to conduct in-depth discussion on the causal relationship between variables. Secondly, the self-report method was adopted in this study, which may have social approval effect, and multiple evaluation methods can be considered in the future. Finally, the average age of the participants is 16 years old, and the coverage group may not be fully representative of teenagers, so it can be considered to expand the sample group to include teenagers of different ages in the future.

Despite some of the above limitations, there are still some innovations in this study. From the perspective of positive psychology, this study is the first to explore and reveal the impact of perceived social support on adolescents NSSI behavior and its internal mechanism, enriching the research on the protective factors of adolescent NSSI behavior, and the results supported the PYD and the main-effect models. To a certain extent, it could promote the application of these theories in adolescent NSSI intervention. In addition, the results of the study suggest that if we provide adolescents with a safe and effective external environment, it can not only directly reduce the occurrence of adolescent NSSI behavior, but also promote the development of their psychological traits, which may also prevent or reduce the occurrence of adolescent NSSI behavior to a certain extent.

Conclusion

Perceived social support can significantly negatively predict adolescent NSSI behavior, that was, the more perceived social support, the lower the frequency of adolescent NSSI. Resilience played a mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior, that was, the effect of perceived social support on NSSI behavior was achieved through the indirect effect of resilience. Furthermore, hope and resilience played a sequential mediating role between perceived social support and adolescent NSSI behavior.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Alloway, R., & Bebbington, P. (1987). The buffer theory of social support–a review of the literature. Psychological Medicine, 17(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700013015

Baharudin, R., & Zulkefly, N. S. (2009). Relationships with father and mother, self-esteem and academic achievement amongst college students. American Journal of Scientific Research, Issue, 6, 86–94.

Benson, P. L., Scales, P. C., Hamilton, S. F., & Sesma, A., Jr. (2006). Positive youth development: Theo-ry, research, and applications. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of chil- d psychology:Theoretical models of human development (pp. 894–941). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0116.

Bresin, K., & Schoenleber, M. (2015). Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-inju-ry: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.009

Brown, R. C., & Plener, P. L. (2017). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(3), 20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0767-9

Cha, K. S., & Lee, H. S. (2018). The effects of ego-resilience, social support, and depression on suicidal ideation among the elderly in South Korea. Journal of Women & Aging, 30(5), 444–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2017.1313023

Chang, S., Guo, M., Wang, J., Wang, L., & Zhang, W. (2020). The influence of school assets on the development of well-being during early adolescence: Longitudinal mediating effect of intentional self-regulation. Acta- Psychologica Sinica, 52(07), 874–885. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2020.00874

Chen, Z., Wang, H., Feng, Y., & Liu, X. (2020). The effects of peer victimization on left-behind Adolescents’Subjective well-being: The roles of self-esteem and social support. Psychological Development and Education, 36(5), 605–614. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2020.05.12

Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., Kashdan, T. B., Heaven, P. C., & Barkus, E. (2015). Hope and emotional well-being: A six-year study to distinguish antecedents, correlates, and consequences. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(6), 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1015154

Colpitts, E., & Gahagan, J. (2016). The utility of resilience as a conceptual framework for und-erstanding and measuring LGBTQ health. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0349-1

Condly, S. J. (2006). Resilience in children: A review of literature with implications for education. Urban Education, 41(3), 211–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085906287902

Esposito, C., Bacchini, D., & Affuso, G. (2019). Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and its rela-tionships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiatry Research, 274, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.018

Etzion, D. (1984). Moderating effect of social support on the stress-burnout relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(4), 615–622. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.69.4.615

Fan, H., Zhu, Z., Miao, L., Liu, S., & Zhang, L. (2018). Impact of parents’ marital conflict o-n adolescent depressive symptoms: A moderated mediation model. Psychological Development and Education, 34(04), 481–488. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2018.04.12

Fox, K. R., Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Kleiman, E. M., Bentley, K. H., & Nock, M. K. (2015). Meta-analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 156–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.002

Fried, Y., & Tiegs, R. B. (1993). The main effect model versus buffering model of shop steward social support: A study of rank-and-file auto workers in the USA. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(5), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030140509

Garisch, J. A., & Wilson, M. S. (2015). Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: Cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0055-6

Geng, Z., Ogbolu, Y., Wang, J., Hinds, P. S., Qian, H., & Yuan, C. (2018). Gauging the effects of self-efficacy, social support, and coping style on self-management behaviors in Chinese cancer survivors. Cancer Nursing, 41(5), E1–E10. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000571

Gold, M. S., & Bentler, P. M. (2000). Treatments of missing data: A Monte Carlo comparison of RBHDI, iterative stochastic regression imputation, and expectation-maximization. Structural Equation Modeling, 7(3), 319–355. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0703_1

Granek, L., Barrera, M., Shaheed, J., Nicholas, D., Beaune, L., D’agostino, N., ... & Antle, B. (2013). Trajectory of parental hope when a child has difficult-to-treat cancer: A prospective qualitative study. Psycho-oncology, 22(11), 2436–2444. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3305.

Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(4), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012779403943

Greenberg, M. T. (2006). Promoting resilience in children and youth: Preventive interventions a-nd their interface with neuroscience. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1094(1), 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1376.013

Gülaçtı, F. (2010). The effect of perceived social support on subjective well-being. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 3844–3849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.602

Hasking, P., Whitlock, J., Voon, D., & Rose, A. (2017). A cognitive-emotional model of NSSI: Using emotion regulation and cognitive processes to explain why people self-injure. Cognition and Emotion, 31(8), 1543–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1241219

Hefner, J., & Eisenberg, D. (2009). Social support and mental health among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79(4), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016918

Hilt, L. M., Cha, C. B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2008). Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.63

Hombrados-Mendieta, M. I., Gomez-Jacinto, L., Dominguez-Fuentes, J. M., Garcia-Leiva, P., & Castro-Travé, M. (2012). Types of social support provided by parents, teachers, and classmates during adolescence. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(6), 645–664. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20523

Hu, Y., & Gan, Y. (2008). Development and psychometric validity of the resilience scale for Chinese adolescents. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 40(08), 902–912.

Huang, Y., Zhao, Q., & Li, C. (2021). How interpersonal factors impact the co-development of depression and non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese early adolescents. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 53(05), 515–526. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2021.00515

Jiang, Y., Ren, Y., Zhu, J., & You, J. (2020). Gratitude and hope relate to adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Mediation through self-compassion and family and school experiences. Current Psychology, 41(2), 935–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00624-4

Jiang, Y., Ren, Y., Liu, T., & You, J. (2021). Rejection sensitivity and adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: Mediation through depressive symptoms and moderation by fear of self-compassion. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 94(s2), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12293

Kalaitzaki, A., Tsouvelas, G., & Koukouli, S. (2021). Social capital, social support and perceived stress in college students: The role of resilience and life satisfaction. Stress and Health, 37(3), 454–465. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.3008

Kemer, G., & Atik, G. (2012). Hope and social support in high school students from urban and rural areas of Ankara, Turkey. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(5), 901–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9297-z

Kiekens, G., Hasking, P., Boyes, M., Claes, L., Mortier, P., Auerbach, R. P., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Green, J. G., Kessler, R. C., Myin-Germeys, I., Nock, M. K., & Bruffaerts, R. (2018). The associations between nonsuicidal self-injury and first onset suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.033

Kirmani, M. N., Sharma, P., Anas, M., & Sanam, R. (2015). Hope, resilience and subjective well-being among college going adolescent girls. International Journal of Humanities & Social Science Studies, 2(1), 262–270.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(2), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002

Kruzan, K. P., & Whitlock, J. (2019). Processes of change and nonsuicidal self-injury: A qualitative interview study with individuals at various stages of change. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 6, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393619852935

Li, Z., & Yin, X. (2015). How social support influences hope in college students: The mediating roles of self-esteem and self-efficacy. Psychological Development and Education, 31(5), 610–617. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2015.05.13

Li, J., Xie, R., Ding, W., Jiang, M., Lin, X., Kayani, S., & Li, W. (2022). Longitudinal relationship between beliefs about adversity and learning engagement in Chinese left-behind children: Hope as a mediator and peer attachment as a moderator. Current Psychology, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02671-x

Lim, K. S., Wong, C. H., McIntyre, R. S., Wang, J., Zhang, Z., Tran, B. X., ... & Ho, R. C. (2019). Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(22), 4581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16224581

Lin, J., Su, Y., Lv, X., Liu, Q., Wang, G., Wei, J., ... & Si, T. (2020). Perceived stressfulness mediates the effects of subjective social support and negative coping style on suicide risk in Chinese patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.026

Luo, R. Z., Zhang, S., & Liu, Y. H. (2020). Relationships among resilience, social support, coping style and posttraumatic growth in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation caregivers. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 25(4), 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2019.1659985

MacKinnon, D. P. (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Routledge.

Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? Investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.3.231.22576

Martin, J., Bureau, J. F., Yurkowski, K., Fournier, T. R., Lafontaine, M. F., & Cloutier, P. (2016). Family-based risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury: Considering influences of maltreat-ment, adverse family-life experiences, and parent–child relational risk. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 170–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.015

Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12205

Masten, A. S., & Gewirtz, A. H. (2006). Resilience in development: The importance of early childhood. In R. E. Tremblay, R. G. Barr, & R. DeV. Peters (Eds.), Encyclopedia on early childhood development. http://www.child-encyclopedia.com/documents/Masten-GewirtzANGxp.pdf

Mattanah, J. F., Ayers, J. F., Brand, B. L., & Brooks, L. J. (2010). A social support intervention to ease the college transition: Exploring main effects and moderators. Journal of College Student Development, 51(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0116

Min, J. A., Yoon, S., Lee, C. U., Chae, J. H., Lee, C., Song, K. Y., & Kim, T. S. (2013). Psychological resilience contributes to low emotional distress in cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21(9), 2469–2476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1807-6

Morley, C. A., & Kohrt, B. A. (2013). Impact of peer support on PTSD, hope, and functional impairment: A mixed-methods study of child soldiers in Nepal. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 22(7), 714–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2013.813882

Mullin, A. (2019). Children’s hope, resilience and autonomy. Ethics and Social Welfare, 13(3), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2019.1588907

Mummé, T. A., Mildred, H., & Knight, T. (2017). How do people stop non-suicidal self-injury? A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 21(3), 470–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2016.1222319

Narayanan, S. S., & Onn, A. C. W. (2016). The influence of perceived social support and self-efficacy on resilience among first year Malaysian students. Kajian Malaysia, 34(2), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.21315/km2016.34.2.1

Nemati, H., Sahebihagh, M. H., Mahmoodi, M., Ghiasi, A., Ebrahimi, H., Atri, S. B., & Mohammadpoorasl, A. (2020). Non-suicidal self-injury and its relationship with family psychological function and perceived social support among Iranian high school students. Journal of Research in Health Sciences, 20(1), e00469. https://doi.org/10.34172/jrhs.2020.04

Nock, M. K., & Favazza, A. R. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 9–18). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11875-001

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutila-tive behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885

Ong, A. D., Edwards, L. M., & Bergeman, C. S. (2006). Hope as a source of resilience in later adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(7), 1263–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.03.028

Ozbay, F., Fitterling, H., Charney, D., & Southwick, S. (2008). Social support and resilience to stress across the life span: A neurobiologic framework. Current Psychiatry Reports, 10(4), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-008-0049-7

Pacico, J. C., Bastianello, M. R., Zanon, C., & Hutz, C. S. (2013). Adaptation and validation of the dispositional hope scale for adolescents. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 26(3), 488–492. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722013000300008

Park, L. E., & Crocker, J. (2008). Contingencies of self-worth and responses to negative interpersonal feedback. Self and Identity, 7(2), 184–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860701398808

Parker, P. D., Ciarrochi, J., Heaven, P., Marshall, S., Sahdra, B., & Kiuru, N. (2015). Hope, friends, and subjective well-being: A social network approach to peer group contextual effects. Child Development, 86(2), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12308

Pejičić, M., Ristić, M., & Anđelković, V. (2018). The mediating effect of cognitive emotion regulation strategies in the relationship between perceived social support and resilience in postwar youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(4), 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21951

Ren, X., Wang, Y., Hu, X., & Yang, J. (2019). Social support buffers acute psychological stres-s in individuals with high interdependent self-construa. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(04), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2019.00497

Rock, E. E., Steiner, J. L., Rand, K. L., & Bigatti, S. M. (2014). Dyadic influence of hope and optimism on patient marital satisfaction among couples with advanced breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22(9), 2351–2359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2209-0

Rubin, H. H. (2008). Hope and ways of coping after breast cancer. University of Johannesburg (South Africa).

Satici, S. A. (2016). Psychological vulnerability, resilience, and subjective well-being: The mediating role of hope. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.057

Schatten, H. T., Andover, M. S., & Armey, M. F. (2015). The roles of social stress and decision-making in non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Research, 229(3), 983–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.087

Simmons, B. L., Gooty, J., Nelson, D. L., & Little, L. M. (2009). Secure attachment: Implications for hope, trust, burnout, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 30(2), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.585

Snyder, C. R. (1996). To hope, to lose, and to hope again. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 1(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325029608415455

Snyder, C. R. (2000). The past and possible futures of hope. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.11

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., ... & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

Snyder, C. R., Hoza, B., Pelham, W. E., Rapoff, M., Ware, L., Danovsky, M., ... & Stahl, K. J. (1997). The development and validation of the Children’s Hope scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 22(3), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/22.3.399

Southwick, S. M., Sippel, L., Krystal, J., Charney, D., Mayes, L., & Pietrzak, R. (2016). Why are some individuals more resilient than others: The role of social support. World Psychiatry, 15(1), 77–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20282

Stewart, D. E., & Yuen, T. (2011). A systematic review of resilience in the physically ill. Psychosomatics, 52(3), 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2011.01.036

Sun, S., Guan, Y., Qin, Y., Zhang, L., & Fan, F. (2013). Social support and emotional-behaviora-l problems: Resilience as a mediator and moderator. Chinese. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21(01), 114–118. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2013.01.025

Syed, S., Kingsbury, M., Bennett, K., Manion, I., & Colman, I. (2020). Adolescents’knowledge of a peerʼs non-suicidal self-injury and own non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(5), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13229

Thippaiah, S. M., Nanjappa, M. S., Gude, J. G., Voyiaziakis, E., Patwa, S., Birur, B., & Pandurangi, A. (2020). Non-suicidal self-injury in developing countries: A review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(5), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020943627

Tian, X., Jin, Y., Chen, H., Tang, L., & Jiménez-Herrera, M. F. (2021). Relationships among social support, coping style, perceived stress, and psychological distress in Chinese lung cancer patients. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing, 8(2), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.4103/apjon.apjon_59_20

Turner, B. J., Cobb, R. J., Gratz, K. L., & Chapman, A. L. (2016). The role of interpersonal conflict and perceived social support in nonsuicidal self-injury in daily life. Journal of Abn-ormal Psychology, 125(4), 588–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000141

Ungar, M., Liebenberg, L., Boothroyd, R., Kwong, W. M., Lee, T. Y., Leblanc, J., & Makhnach, A. (2008). The study of youth resilience across cultures: Lessons from a pilot study of measurement development. Research in Human Development, 5(3), 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600802274019

Wang, L. Y., Chang, P. C., Shih, F. J., Sun, C. C., & Jeng, C. (2006). Self-care behavior, hope, and social support in Taiwanese patients awaiting heart transplantation. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 61(4), 485–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.11.013

Wang, Y., Chen, H., & Yuan, Y. (2020). Effect of social exclusion on adolescents’ self-injury: The mediation effect of shame and the moderating effect of cognitive reappraisal. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(2), 333–339. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200211

Waugh, C. E., Thompson, R. J., & Gotlib, I. H. (2011). Flexible emotional responsiveness in trait resilience. Emotion, 11(5), 1059–1067. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021786

Wu, H. (2011). The protective effects of resilience and hope on quality of life of the families coping with the criminal traumatisation of one of its members. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(13–14), 1906–1915. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03664.x

Xiang, G., Teng, Z., Li, Q., Chen, H., & Guo, C. (2020). The influence of perceived social support on hope: A longitudinal study of older-aged adolescents in China. Children and Youth Services Review, 119(c), 105616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105616

Yamada, Y., Klugar, M., Ivanova, K., & Oborna, I. (2014). Psychological distress and academic self-perception among international medical students: The role of peer social support. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-014-0256-3

Yucens, B., Kotan, V. O., Ozkayar, N., Kotan, Z., Yuksel, R., Bayram, S., ... & Goka, E. (2019). The association between hope, anxiety, depression, coping strategies and perceived social support in patients with chronic kidney disease. Dusunen Adam The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 32(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.14744/DAJPNS.2019.00006

Zhang, J., Gao, W., Wang, P., & Wu, Z. H. (2010). Relationships among hope, coping style and social support for breast cancer patients. Chinese Medical Journal, 123(17), 2331–2335. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2010.17.009

Zhang, M., Zhang, J., Zhang, F., Zhang, L., & Feng, D. (2018). Prevalence of psychological distress and the effects of resilience and perceived social support among Chinese college students: Does gender make a difference? Psychiatry Research, 267, 409–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.038

Zhao, J., & Li, Z. (2017). The relationships between parent-child attachment and adolescent anxiety: The protective role of teacher’s support. Psychological Development and Education, 33(03), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.16187/j.cnki.issn1001-4918.2017.03.14

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhifan Yuan (Conceptualization; Methodology; Validation; Software; Writing–original draft). Weijian Li (Supervision; Project administration; Writing–review & editing). Wan Ding (Supervision; Project administration; Writing–review & editing). Shengcheng Song (Formal analysis; Investigation). Lin Qian (Formal analysis; Investigation). Ruibo Xie (Supervision; Project administration; Writing–review & editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Z., Li, W., Ding, W. et al. Your support is my healing: the impact of perceived social support on adolescent NSSI — a sequential mediation analysis. Curr Psychol 43, 261–271 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04286-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04286-w