Abstract

Drawing on the tenets of conservation of resources theory and social identity theory, this study examined the influence of workplace incivility on organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) through the mediating effect of work engagement. Simultaneously, the moderator effect of organizational identity on the relationship between workplace incivility and work engagement is analyzed. Using the data collected from 484 full time employees from hi-tech, banking and manufacturing industries, it is found that work engagement fully mediates the relationship between workplace incivility and OCB. Furthermore, it is found that the adverse impact of workplace incivility is higher for employees with greater organizational identification, implying that experiencing workplace incivility can be more devastating for employees who see their organization as an integral part of their identity. This study contributes to the literature by jointly testing the mediating role of work engagement and moderator role of organizational identity to understand the relationship between workplace incivility and OCB. Drawing on the findings, both theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Deviant behaviour within the workplace has become a popular topic in the organizational behaviour literature over the last two decades. Numerous studies have examined how different types of destructive workplace behaviours affect results at the organizational, group, and individual levels (Schilpzand et al., 2016). Specifically, most of the studies mainly explored the negative impacts of adverse behaviours on employees’ job-related behaviours, and welfare, emphasising issues such as workplace aggressiveness, deviance, bullying, and abusive supervision (Schilpzand et al., 2016). Workplace incivility, a comparatively newly added concept to the field of deviant workplace behaviour, refers to impolite, disdainful, and excluding actions that interrupt workplace norms of respect but otherwise seem dull (Schilpzand et al., 2016; Cortina et al., 2017). Defined as “low-intensity deviant behaviour with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect” (Andersson & Pearson, 1999, p. 457), uncivil behaviours usually involve sarcasm, condescension, denigrating others, making condescending comments, subtly disapproving comments as well as nonverbal demonstrations of impertinence such as ignoring (Porath and Pearson, 2012; Cortina et al., 2013; Schilpzand et al., 2016). Even though workplace incivility does not receive as much legal responsiveness as other counterproductive workplace behaviour constructs such as sexual harassment (Lim et al., 2008), it is highly common in the workplace than other negative workplace behaviours (Rosen et al., 2016), and studies have shown that the occurrence of workplace incivility is rising (Liu et al., 2019). For instance, Cortina et al. (2001) found that 71% of 1180 employees had been exposed to uncivil behaviours in the previous five years. For instance, Porath & Pearson (2013) found that 98% of the employees reported experiencing workplace incivility and were treated rudely at least once a week. However, despite being emphasized as a subdued stressor, workplace incivility, compared to other major but time-limited stressors, has been found to cause more psychological and physical harm, such as increased turnover intention, work withdrawal, workplace deviance, stress, and decreased task performance, psychological well-being, organizational commitment, and organizational citizenship behaviour (for reviews, see: Schilpzand et al., 2016; Cortina et al., 2017; Vasconcelos, 2020).

Based upon the prior studies, this study aims to enhance our knowledge about the underlying mechanisms through how workplace incivility may influence OCB, a relatively less examined consequence of workplace incivility in terms of the mediating and moderating mechanisms that influence the relationship between these two concepts (Liu et al., 2019), leaving a significant research gap that this study will cover. Specifically, relying on the conservation of resources theory (COR) (Hobfoll, 1989), work engagement is examined as a possible intervening variable in the relationship between workplace incivility and OCB. In particular, work engagement is currently a popular topic within many organisations, given its association with employee well-being and performance (Knight et al., 2017). Appraising, improving and enduring work engagement are thus a crucial concern of many organisations because work engagement can be seen as a dynamic state where employees experience constructive work-related affect (Wang et al., 2015). However, targets of workplace incivility may not be able to be fully engaged at work because they are concerned about maintaining their well-being (Gopalan et al., 2022). Instead, they are more likely to experience anxiety or frustration but less positive affect (Wang et al., 2015), which may result in less OCB.

Furthermore, drawing on social identity theory (Richter et al., 2006), we examined organizational identification as a moderator of the mechanism between workplace incivility and work engagement to understand the question of who is more affected by workplace incivility.

The contribution of the study is twofold. The first contribution is based on examining the causal mechanism through which workplace incivility may influence OCB. Schilpzand et al. (2016) argue that the number of studies examining how and through which mechanisms workplace incivility influences its consequences is comparatively limited, and OCB is not an exception. The authors also emphasized that it would be beneficial to go beyond studying direct effects and “investigate mediators, moderators, and boundary conditions of the impact of incivility on attitudes, behaviours and outcomes.” Specifically, prior research generally relied on tit for tat argument, discussing that the targets of uncivil behaviours may tend to retaliate against the initiators or their organizations (Liu et al., 2019) by decreasing their effort (Taylor et al., 2012). On the other hand, Liu et al. (2019) found that the targets of uncivil behaviours decrease their OCB, arguing that the tit-for-tat approach might not be sufficient to elucidate the decreased OCB of the target as a reaction to uncivil behaviour. Moreover, they also found that burnout mediated the relationship between workplace incivility and OCB. Hence, according to these findings, it might be argued that the victims of uncivil behaviours may decrease their OCB for more than one reason, and further studies examining the underlying mechanism are essential to understand possible additional mechanisms through which workplace incivility may influence OCB. This study argues that the victims of incivility are too worried about preserving their resources that they cannot concentrate on their work and withdraw their engagement so that they cannot engage in extra-role behaviours.

The second contribution of this study, noticing the call of Schilpzand et al. (2016) for a keen focus on using moderators to better grasp the nature of incivility, is based on examining the moderating effect of organizational identification, which seeks to answer the question of who is more affected by the adverse consequences of workplace incivility. Relying on social identity theory, organizational identity is conceptualized as a particular form of social identity that refers to how a person identifies himself-herself as a member of a specific organization (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). When people identify themselves as belonging to an organization, they tend to develop a sense of their values and expectations of their role in the organization (Huang & Lin, 2019). Such identification causes them to place greater psychological demands on their expectations. Previous research has shown that organizational identity interacts with employee perceptions to regulate altruistic and prosocial behaviour (Huang & Lin, 2019). In other words, organizational identity can strengthen employee responses when confronted with workplace deviations (Evans & Davis, 2014). According to social identity theory, people with higher levels of organizational identity are more sensitive to the social norms of their organizations. More specifically, employees with high organizational identities have a strong desire to be treated fairly and respected to remain psychologically connected to their organization (Huang & Lin, 2019). We argue that organizational identification will have a moderator role in this mediated relationship. Specifically, high levels of organizational identification will increase the adverse impact of uncivil behaviours on work engagement, and OCB is lower than when organizational identification is high. Thus, our aim is not only based on proposing and testing the underlying mechanism by which workplace incivility influences OCB but also based on examining who is most affected. Such findings may contribute to the literature about the potential influences of organizational identification in dealing with workplace stressors, such that employees with higher identification levels are more vulnerable to workplace stressors and more likely to suffer a decrease in their positive work outcomes, such as OCB.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

Workplace incivility

Studies on harassment and aggression within the workplace have attracted researchers’ interest since the late 1980s (Neall & Tuckey, 2014) and gained significant popularity during the 1990s (Hershcovis, 2011; Young et al., 2021). The studies have yielded numerous constructs, including bullying, mobbing, abusive supervision, social exclusion, and incivility. Even though workplace incivility has similarities with other counterproductive workplace behaviours, it has significant characteristics that make it distinctive from other workplace deviance behaviours, which show variation among each other in terms of intensity, intent, and frequency (Young et al., 2021). Specifically, workplace incivility, distinct from other types of negative workplace behaviours, is based on low intensity and ambiguous intent (Pearson & Porath, 2005). For instance, interrupting another party during a meeting, speaking in a patronizing tone, or making belittling remarks are examples of low-intensity uncivil behaviour. Furthermore, unlike other counterproductive workplace behaviours, of which the aim is to harm the target, the intention of the incivility instigator is vague (Pearson & Porath, 2005). Accordingly, the mundane aspect of uncivil behaviours is also noteworthy. Specifically, even though uncivil behaviours are impolite, arrogant, and excluding and violate the workplace values of respect, they can look to be ordinary occurrences (Cortina et al., 2017). Therefore, while an instigator may be rude or uncivil on purpose, it is also possible that the instigator did not intend to do so. As a result, incivility victims might devote a significant amount of time and energy to identifying the motives of instigators following uncivil behaviour. The time and energy spent evaluating the uncivil confrontations may divert the targets’ attention away from their jobs, draining their mental resources (Liu et al., 2019).

Incivility, whether experienced or witnessed, can have a detrimental influence on individuals, workgroups, and businesses (Cortina, 2008; Cortina et al., 2017;). Incivility among employees can lead to tense working relationships, a lack of organizational commitment, higher turnover, anxiety, and strain, as well as lower job satisfaction and self-esteem (Cortina, 2008). In other words, the greater incivility a person encounters, they are less likely to be satisfied with their job, the more anxious they get, the more likely they are to leave their position, and the more likely to engage in extra-role behaviour (Cortina et al., 2017).

Workplace incivility and COR Theory

COR theory proposes that individual resources are limited, and individuals try to obtain, keep, and conserve their physical, emotional, social and psychological resources to achieve their goal attainment, such as improving individual well-being or work performance, and have the propensity to obviate resource deprivation, particularly in undesirable occurrences (Hobfoll, 2001). COR theory classifies four types of resources: objects (shelter or clothing), conditions (status at work), personal characteristics (self-esteem or occupational skills), and energy resources (time or knowledge). If these resources are jeopardized, vanished or are not satisfactorily refilled, they are more likely to experience negative mental conditions, such as increased stress, perceived risk of resource loss, sadness or even hostility (Lyu et al., 2016). Furthermore, according to COR theory, social relationships can also be identified as unique resources that can deliver and drain the resources described above (Hobfoll, 2001). Even though workplace incivility is considered a comparatively minor form of social hassle, it still drains employees’ emotional and mental resources and significantly impacts an individual’s well-being in the long term as these micro-aggravations accumulate over time (Sliter et al., 2010). For instance, victims of uncivil behaviours may perceive the situation as a risk to their well-being or to their social status within the work environment. To circumvent additional resource deprivation, employees may withdraw from accomplishing their workplace responsibilities because workplace incivility is mentally and emotionally demanding. For instance, Giumetti et al. (2013) found that workplace incivility is associated with lower energy levels, then, in turn, resulting in decreased job performance. In other words, when an employee has used up resources because of coping with uncivil behaviours, it is highly likely that the employee may be short of resources to accomplish organizational goals. Accordingly, based on COR theory’s tenets, current research considers workplace incivility as a resource-draining incidence. In return for this fatigue, employees may demonstrate withdrawal from work and reduced levels of extra-role behaviours.

Workplace incivility and OCB

OCB is defined as “individual behaviour that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Organ, 1988, p. 4). Higher OCB is desired by organizations due to its contribution to creating a constructive work atmosphere and increased employee performance (MacKenzie et al., 2018). However, employees may respond with lower OCB when exposed to unpleasant workplace encounters. In particular, employees who experience more workplace stressors, such as abusive supervision and workplace bullying, were less likely to engage in OCB, according to studies of other workplace mistreatment characteristics (e.g., Lyu et al., 2016). Workplace incivility, which is identified as a workplace stressor (Cortina & Magley, 2009), may cause psychological distress and emotional strain for employees (Liu et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2022). According to prior research, experiencing workplace incivility may negatively influence employees’ attitudes about their organization and their performance (Taylor et al., 2012; Mao et al., 2019). Specifically, Taylor et al. (2012) argue that employees with unfavourable exchange relations are more likely to refuse to exceed minimum performance criteria or go above and beyond their responsibilities. Furthermore, employees confronted with incivility in the workplace have been demonstrated to be more hesitant to engage in these extra-role behaviours (Sliter et al., 2010; Taylor et al., 2012; Mao et al., 2019). Taken together, we developed the first hypothesis as follows:

H1: Workplace incivility negatively affects the OCB of employees

The mediating role of work engagement

Even though the existing research on workplace incivility has examined and identified numerous antecedents and outcomes, it has been criticized about been limited to investigating the direct influence of incivility instead of examining the underlying mechanism and surrounding effects. As Schilpzand et al. (2016: 68) emphasized that “investigate mediators, moderators, and boundary conditions of the impact of incivility on attitudes, behaviours and outcomes”, this study notices this call for a keen focus on examining the indirect effects of other variables to better grasp the underlying nature of workplace incivility.

Work engagement is defined as a “positive, fulfilling work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., 2002: 74). Vigor refers to the tendency to put effort into one’s work, tenacity in the face of task-related problems, and demonstration of high levels of energy while working. Dedication is defined as being deeply invested in one’s work and feeling a sense of importance, passion, and challenge. Finally, absorption is defined as being completely focused and favourably absorbed in one’s work. In summary, work engagement describes how people feel about their jobs: engaged employees are more enthusiastic and effective at their jobs, and they are more motivated (Kuijpers et al., 2020).

According to Kahn (1990), highly engaged employees integrate their values and work to realize their physiological, mental, and emotional selves, allowing them to take the ascendency and be committed to their work. On the other hand, workplace incivility may also cause psychological distress for employees. Specifically, experiencing uncivil behaviours in the workplace makes employees feel vulnerable and lowers their work engagement level (Guo et al., 2022). According to COR theory, individuals naturally desire to obtain, keep, and defend the resources they appreciate (Hobfoll, 2001). Besides, individuals will experience psychological distress if they are faced with resource loss or the failure to achieve returns after investing in resources (Guo et al., 2022). As a result, it is possible to suppose that when confronted with workplace incivility, people can experience emotional stress and get exhausted from dealing with it. Thus, such a practice will deplete individuals’ restricted resources, leading to distress, inability to concentrate on their work, and a decrease in work engagement. (Guo et al., 2022).

Decreased work engagement resulting from workplace incivility may also weaken individuals’ organizational citizenship behaviour. Individuals often start a new work feeling engaged rather than burned out, according to Maslach et al. (2001). Work that is pleasing and significant might, nevertheless, become unrewarding and insignificant under stressful circumstances. According to the COR principle, workplace incivility might operate as social contact stress, draining targets’ resources and lowering their energy to complete other responsibilities. Consequently, if workplace stressors cause employees to lose their resources, employees may look for alternative ways of preserving and returning those resources, such as decreasing their OCB. Disengaged employees, who are separated from their job, are not fully concentrated on their work, and they are unlikely to see their work worth investing in extra effort and may not have a broad understanding of their duties (Lyu et al., 2016). Therefore, the targets of uncivil behaviours, with little commitment and enthusiasm for their work, may hesitate to engage in discretionary citizenship behaviour. Furthermore, compared to in-role behaviours, OCB requires more energy and resources due to their discretionary nature. Disengaged employees, on the other hand, may lack energy and struggle to perform even their in-role obligations. (Christian et al., 2011). Thus, going the extra mile beyond the boundaries of job responsibilities may be less likely for disengaged employees because they lack such immersion and passion for the effective execution of duties, resulting from workplace incivility. Based on the discussion above, we argue that workplace incivility inhibits the growth of work engagement, resulting in a lower level of OCB. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Work engagement mediates the relationship between workplace incivility and OCB.

The moderating role of organizational identification

Organizational identity, derived from the theory of social identity, is understood as a particular form of social identity related to how one defines himself-herself as a member of a particular organization (Mael & Ashforth, 1992). Employees that identify themselves with the organization feel a unity between themselves and the organization (Mael & Ashforth, 1992; Liu et al., 2019). Organizational identification can trigger employee responsiveness when faced with workplace deviation (Evans & Davis, 2014). According to social identity theory, employees, who have higher levels of organizational identification, are more conscious of the collective norms of the organizations they identify with (Mael & Ashforth, 1992), which makes the influence of workplace incivility on work engagement more salient (Huang & Lin, 2019). Specifically, some scholars argue that organizational identification may strengthen the consequences of stressors as more identified employees invest more and become equated with the organization (Evans & Davis, 2014; Huang & Lin, 2019). In particular, to maintain their emotional affiliation with the organization, employees with greater organizational identification are more eager to be treated and valued fairly (Epitropaki, 2013; Huang & Lin, 2019). Accordingly, when employees encounter uncivil behaviours, which violate the collective norms of the organizations they identify with, their emotional reaction, namely engaging in their work, might be higher. In contrast, because the employees with a lower level of organizational identity lack the sensitivity of oneness with or unity to the organization, they might be less sensitive to workplace incivility, causing a reduced impact of workplace incivility on workplace engagement. Therefore, the following hypothesis is generated:

H3: Organizational identification will moderate the relationship between workplace incivility and workplace engagement. Specifically, the negative effect of workplace incivility will be stronger when organizational identification is high compared to when it is low.

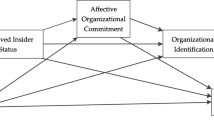

Figure 1 demonstrates the developed model in the study.

Method

Procedure and participants

We used a cross-sectional design to test the proposed theoretical model. Using personal and official contacts, such as university-industry collaboration offices at the authors’ universities, potential respondents in the target organizations were reached by both authors. An e-mail invitation was sent to 1,486 employees in the hi-tech, banking and manufacturing industries in Turkey, requesting them to contribute to an anonymous online survey. In the e-mail, we included a cover letter and an informed consent form. Moreover, the following information is also provided to the participants: (1) a statement that emphasizes that participation in the survey is totally voluntary, and all the results will be recorded as anonymous, and (2) a statement that the information provided will be used for research purposes only and will be reported in aggregate form only. 874 e-mails were returned as non-deliverable, and 128 participants did not complete the survey, which resulted in 484 possible subjects for the study, yielding a response rate of 32.5%. 43 per cent of the sample were female respondents (208), the average age was 35.8 years (SD = 8.9), and the average organizational tenure was 6.7 years (SD = 3.1).

Measurement

Workplace Incivility. To measure perceived incivility over the past year, a 7-item workplace incivility scale (Cortina et al., 2001) was used. Sample item includes “How often have you experienced the following behaviours at work? Your superior or co-worker like to make demeaning or derogatory remarks about you?” Participants rated the frequency of experiencing incivility using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = never to 5 = Very often (almost every day). (α = 0.88).

Organizational Identification. To measure organizational identification, a six-item OI scale developed by Mael and Ashforth (1992) was used. The participants rated each statement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Sample item includes ‘‘When someone criticizes my company, it feels like a personal insult.’’ (α = 0.87).

Work Engagement. to measure work engagement, a nine-item scale developed by Schaufeli et al. (2006) was used. The participants rated each statement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Sample item includes “At my work, I feel bursting with energy.” (α = 0.89).

Organizational Citizenship Behaviour. To measure OCB, we used a 10-item scale developed by Spector et al. (2010). Participants rated the items using a 5-point frequency scale (1 = never; 5 = every day). Sample item includes “Gave up meal and other breaks to complete work.” (α = 0.95).

Control variables. The tenure of the participants was controlled because of its possible link with task OCB and deviant workplace behaviour (Ng & Feldman, 2010). We also measured gender as a control variable because previous studies have demonstrated that incivility targets’ gender might have an influence on their vulnerability to uncivil behaviour (Itzkovich & Dolev, 2017). In addition, age was also controlled because having a longer age may yield more opportunities or occurrence of experiencing uncivil behaviours at the workplace.

Lastly, even though Chen and Lin (2014) suggest that examination of interaction effects (moderator role of OI in this study) may alleviate the common method bias (CMB) threat, we still included social desirability as a control variable to avoid any potential CMB threat. During the data collection, because some of the constructs included in this study were measured with sensitive questions, such as incivility, the participants’ anonymity and confidentiality were ensured and emphasized both in the e-mail and on the survey cover page. To measure social desirability, we used a 4-item scale developed by Fisher (1993). The participants rated each statement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The sample item includes “I am always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable.” (α = 0.73). (mean = 2.44, SD = 0.66). Following Grappi et al. (2013), we performed a one-sample t-test analysis and compared the sample mean and the value mean of the scale (3). It was found that the respondents showed low levels of social desirability (-2.29, p < .01). Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the variables are given in Table 1.

Analytical approach

Before performing the primary analyses, to evaluate the factor structure of the study’s variables (Workplace Incivility, Work Engagement, Organizational Citizenship Behaviour and Organizational Identity), we first ran a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) by using AMOS version 24. The item parceling method was used to build the model because of the concern about the item sample size ratio, which was recommended to be 1:20 by Kline (2011). Item parseling, also known as partial decomposition modelling, is beneficial because it decreases the optimum sample size to variable ratio and suggests computational advantages such as higher commonality of parameter estimates, fewer errors, and better fitting results (Williams & O’Boyle Jr, 2008; Evens & Davis, 2014). In the analysis process, following the recommendations of Williams and O’Boyle Jr (2008), we randomly developed three parcels for each latent construct to confirm that every single variable was independently justified. The four-factor model revealed a well fit with CMIN/DF = 1.940; χ2 = 93.133, df = 48; p < .01; IFIFootnote 1 = 0.989; TLIFootnote 2 = 0.985; GFIFootnote 3 = 0.969; CFIFootnote 4 = 0.989; AGFIFootnote 5 = 0.950; SRMRFootnote 6 = 0.035 RMSEAFootnote 7 = 0.044.

Hypothesized structural model

We used PROCESS (Hayes, 2013), Model 7 of the SPSS macro. This allowed us to test both the direct and indirect effects of mediation and moderated mediation models while running the bootstrap model, which provided 95% bias-adjusted confidence interval estimates for these models. SPSS PROCESS macros can also involve numerous control variables, and all continuous variables used in the analysis were standardized.

Results

Direct and mediated Effects

The PROCESS macro Model 4 (Hayes, 2013) was used to analyse mediation paths, as indicated by the unstandardized regression coefficients in Table 2. Workplace incivility was found to be negatively related to organizational citizenship behaviour (b = − 0.64 p < .001), supporting hypothesis 1. According to the analysis results, workplace incivility was also found to be negatively associated with work engagement ((b = − 0,34 p < .001). The bootstrapped indirect effect of workplace incivility on OCB through work engagement was − 0.12 with a confidence interval of 95 per cent and didn’t contain zero (b = – 0.15, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [− 0.2065, − 0.1072]). Work engagement was significantly and positively associated with OCB after controlling workplace incivility. Thus, our hypothesis 2, which argues that work engagement mediates the relationship between workplace incivility and organizational citizenship behaviour, was supported. These results are consistent with our hypothesis that the negative effect of workplace incivility on organizational citizenship behaviour is mediated by work engagement, as shown in Table 2.

Moderated mediation analysis

Moderated mediation refers to the direction and the strength of mediation effects are dependent on another moderator variable. In this study, Hypothesis 2 is based on the fact that the impact of workplace incivility on organizational citizenship behaviour through work engagement is dependent on employees’ level of organizational identification. To understand how the intervening effect of work engagement is moderated, we examined whether the strength of the relationship between workplace incivility and OCB, mediated through work engagement, is significantly different when employees possess different levels of organizational identification. In order to test mediated moderation, PROCESS macro model 7 was used, with 5000 bootstrap samples for bias adjustment and to obtain 95% confidence intervals (Hayes, 2013). Bootstrapping is beneficial because it provides the ability to predict the sample distributions of the moderated mediation model to generate confidence intervals without making assumptions about the shape of the sample distribution (Hayes et al., 2017). Prior to the analysis, as Aiken et al. (1991) recommend, the predictor and moderating variables are gran mean-centred. Taking the recommendations of Preacher et al. (2007) into account, the bootstrapped conditional indirect effects of organizational identity were operationalized at three different levels: one standard deviation below the mean, the mean, and one standard deviation above the mean. Table 3 demonstrates how organizational identity moderates the relationship between workplace incivility and organizational behaviour, where the relationship is mediated by work engagement, including bootstrap effects and confidence intervals. As presented in Table 3, workplace incivility has a statistically significant negative impact on organizational citizenship behaviour at 1 SD below the mean (indirect effect = − 0.0726, 95% CI [− 0.12, − 0.02]), at the mean level (indirect effect = − 0.1262, 95% CI [− 0.17, − 0.08]), and at 1 SD above level (indirect effect = − 0.1798, 95% CI [− 0.24, − 0.12]). As depicted in Fig. 2, the negative effect of workplace incivility on work engagement is higher for employees with higher organizational identity. Taking all these results into account, hypothesis 3 is supported.

Discussion

Drawing on the arguments of COR theory, this study intended to examine the mechanism between workplace incivility and OCB by examining the mediating and moderating mechanisms of this relationship. According to the results, it is found that workplace incivility affects employees’ OCB by reducing their willingness to demonstrate extra-role behaviour. These findings contribute to the literature in several ways.

First, this study examined the moderator role of organizational identification and the mediator role of work engagement together to understand the effect of workplace incivility on OCB that has not yet been examined. By doing so, we contribute to this research gap by concurrently examining the potential relationships based on COR theory and social identity theory.

Second, current research also fills the gaps in the literature by revealing the ‘black box’ that underlies the association between workplace incivility and OCB. While prior research has suggested that workplace incivility may be associated with reduced effort (Taylor et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2022; Onaran & Göncü-Köse, 2022), it is also emphasized that the way how incivility affects job performance has relatively attracted less attention (Schilpzand et al., 2016; Katz et al., 2019). Drawing on the arguments of COR theory, our study shows a new mechanism to understand the influence of workplace incivility on OCB; that is, the negative impact of workplace incivility on OCB is mediated by work engagement, which is consistent with the arguments of COR (Hobfoll, 2001), which argues that workplace stressors trigger mental distress in employees, leading to the anxiety of the loss of important resources, resulting in a decreased job performance. Specifically, workplace incivility, which is a workplace stressor for employees, may cause employees to decrease their work engagement, and, thus, employees reduce their extra-role behaviours in order to preserve their resources. Similar to Liu et al. (2019), Guo et al. (2022), and Onaran and Göncü-Köse (2022), it is found that when employees experience workplace incivility, they lower their OCB, and work engagement serves as a chain mediating effect in the relationship between workplace incivility and OCB. In particular, this finding argues a new mechanism in terms of understanding the effects of workplace incivility on OCB, as the victims of uncivil behaviours may withdraw from work and have fewer resources to engage in OCB. This result contributes to the literature by arguing that instead of engaging in retaliation behaviour in return for workplace incivility, employees may also decrease their input in order to balance the negative effects of workplace incivility (Taylor et al., 2012).

Third, realizing how and to whom workplace incivility influences work outcomes is important for contributing to the literature and coming up with policies to alleviate negative consequences. However, as Taylor et al. (2012) and Schilpzand et al. (2016) emphasize, the number of studies that have focused on this issue is limited and still needs further examination. For instance, Taylor et al. (2012) revealed that the indirect influence of workplace incivility on OCB is transferred by affective commitment, and the strength of this effect is stronger for individuals who have a higher conscientious level. Chen et al. (2013) found that workplace incivility negatively influences work engagement, which in turn negatively affects job performance as well. The authors also found that these relations are stronger for narcissistic individuals. Jawahar and Schreurs (2018), similar to our findings, found that supervisor incivility negatively affects work engagement, which then reduces employees’ OCB, and these relations are stronger for employees who have higher levels of supervisor trust. More recently, Liu et al. (2019) found that workplace incivility increases employees’ level of burnout, which then reduces employees’ OCB, and employees with higher levels of affective commitment suffer from this interaction more. This study contributes to this line of research by arguing that workplace incivility reduces employees’ work engagement and then their OCB, and this relationship is significantly stronger for employees with higher levels of organizational identification. Even though the positive consequences of organizational identity are highly emphasized and recognized (He & Brown, 2013), the results of this study highlight that a higher level of organizational identity does not alleviate the negative consequences of workplace incivility; instead, it does intensify those negative consequences. Taking the tenets of COR theory and social identity theory into account, this result implies that the negative effects of workplace incivility are more harmful to employees with higher levels of organizational identification as they see their organization as an important part of their individual identity. According to the study findings, experiencing workplace incivility may jeopardise the employees’ attachment to their organization, especially for the ones with higher identification, because those employees are more sensitive to the internal dynamics of the organization and, thus, results in a decrease in their personal resources and making them withdrew from their work. This finding proposes that workplace incivility is harmful to OCB because workplace incivility, as a workplace stressor, interrupts employees’ focus and makes them more concerned with uncivil behaviour instead of engaging in their organizational goals, especially when the employees have higher levels of identification with their organization. This argument is consistent with the findings of Porath and Erez (2007) and Jawahar and Schreurs (2018), who argue that workplace incivility shifts the employee’s focus from work by interrupting cognitive processes and impedes the personal resources allocated to job performance. Moreover, this finding is also important and noteworthy because organizational identification has a negative relationship with both work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviour (see Table 1) when employees experience incivility. In other words, organizational identification, which is generally accepted as a beneficial concept for organizations (Ashforth et al., 2008; He & Brown, 2013), may backfire when a workplace stressor is at play. In contrast to the prior studies, which have argued that organizational identification may buffer the perceived strain and advance mental welfare, this study argues that organizational identification may exacerbate the effects of the stressors instead of enhancing employees’ tolerance. This argument is consistent with Evans and Davis’ (2014) claim that organizational identification can intensify employees’ response when they experience workplace deviance. In particular, in order to sustain their identification with the organization, employees with higher levels of OI are more worried about the way they are treated (Huang & Lin, 2019). On the other hand, our findings suggest that employees with a low sense of belonging to their organization are less sensitive to workplace incivility because they lack the perceptions of attachment to an organization, thus resulting in a diminished influence of workplace incivility on work engagement.

Practical implications

Workplace incivility, unfortunately, is a widespread phenomenon in modern organizations Schilpzand et al. (2016), and almost 98 per cent of employees has experienced incivility in their career (Porath & Pearson, 2013) and, according to business reports (Mann & Harter, 2016), less than 15 per cent of the employees are engaged in their work, causing unproductivity. So, we assume our findings may yield practical implications for managers and organizations.

First, this study found that workplace incivility negatively affects employees’ extra-role behaviour by decreasing their work engagement. To handle the adverse results of workplace incivility and increase positive work outcomes, organizations and managers should execute proactive policies to stop workplace incivility before it happens. For instance, selection processes should be based on detecting and eliminating people with deviant behaviour tendencies. This can be done by strictly inspecting candidates’ references. Even though it may appear as a time-consuming action in the short term, it is highly likely to yield a positive return in the long term through having an incivility-free workplace where productivity may increase. In particular, according to Pearson and Porath (2005), companies that have achieved generating a civil workplace claim that such a selection process is one of the best ways of eliminating hiring typical incivility initiators.

Second, once selected, organizations should focus on delivering a code of conduct and organizational culture that emphasizes appropriate civil behaviours within the workplace. At this point, executing a zero-tolerance to incivility policy, which is regularly repeated both orally and in written format, may also help generate an incivility-free workplace as well. At this point, according to Leiter et al. (2012), the Civility, Respect, and Engagement program in the workplace (Osatuke et al., 2009) is recommended as a beneficial program to eliminate workplace incivility. As workplace incivility negatively impacts both work engagement and OCB and decreases productivity, it might be useful to consider workplace incivility in the performance appraisal as well (Loh et al., 2021; Guo et al., 2022). By doing so, the repetitive cycle of uncivil behaviours may weaken in the long term. This may yield important returns because, as this research found that workplace incivility reduces OCB through decreasing work engagement, workplace incivility is not a phenomenon that can be eliminated within a short period of time; instead, it requires a systematic and continuous approach.

Third, this study also found that organizational identification moderates the relationship between workplace incivility and work engagement, highlighting that employees with greater organizational identification are more likely to withdraw from their work when they experience or see uncivil behaviours within the organization. This is a reasonable result because employees may detect an inconsistency between what their organization stands up for and what its employees experience, resulting in cognitive dissonance and higher levels of disengagement from work. Therefore, it is important for organizational members, especially middle and top managers, to stick with ethically appropriate social norms and civil codes of conduct both to eliminate inconsistency and to deliver clear messages. In addition, since employees with a higher degree of organizational identity are more likely to internalize the values of the organization, it can be expected that they are more likely to take action and complain of incivility. Therefore, it is important for managers to take those complaints into account and examine them as well.

Limitations and further research

This study has several limitations that should be emphasized. First, our data were unavoidably gathered from a single source and through self-reporting, which may cause the results of this study to be susceptible to single-source bias. Nonetheless, as noted before, single source bias, as a CMB, is less likely to be a concern for the interaction effect. Furthermore, even though it is recommended to collect other-reported OCB data, Carpenter et al. (2014) found that both self-reported OCB data and other-reported OCB data demonstrate parallel correlation patterns with some common variables. Therefore, although we aimed to state these concerns, future studies may collect data from multisource (customers, colleagues, or supervisors) or gather diary data or critical incidents to test our model again. Second, considering the effects of incivility over time, our cross-sectional design of the research may constrain the interpretations of the study results. Even though cross-sectional data increases the response rate, data collected over time may increase the strength of causal inference as well. Thus, future studies may consider supplementary data-collecting methods, such as diary data, panel data or experiment design, to better understand the reactions of incivility victims. Lastly, in this study, the source of incivility is not differentiated, whether it is the supervisor or a co-worker. According to Schilpzand et al. (2016), because supervisors have direct authority over their employees, supervisor incivility can affect outcomes more than other causes, such as co-workers. On the other hand, previous studies have noted that workplace incivility causes poorer OCB, regardless of the source of the behaviour (Porath & Erez, 2007). However, because our focus in this study is on organizational identity, employees with greater levels of organizational identification may be more sensitive to managerial incivility than their peers. Therefore, it is important that future studies may address and distinguish the sources of incivility and elucidate whether the source of behaviour matters.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study is to examine the impact of workplace incivility on OCB through the indirect effect of work engagement and for whom this impact is stronger. Using the conservation of resources theory and social identity theory, we found evidence that workplace incivility has a significant negative influence on OCB, and this influence is mediated by workplace engagement. Moreover, this indirect effect is greater for individuals with higher levels of organizational identification. Taking the results into consideration, the study results emphasize the negative impact of workplace incivility on organizational citizenship behaviour through work engagement and provide further evidence about the significance of organizational identification in terms of intensifying the harmful effects of workplace stressors instead of acting as a buffer between the stressor and work outcome.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Incremental Fit Index.

Tucker- Lewis Index.

Goodness of Fit Index.

Comparative Fit Index.

Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index.

Standardized Root Mean Square Residual.

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471.

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: an examination of four fundamental questions. Journal of Management, 34(3), 325–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

Carpenter, N. C., Berry, C. M., & Houston, L. (2014). A meta-analytic comparison of self‐reported and other‐reported organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(4), 547–574. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1909

Chen, M. L., & Lin, C. P. (2014). Modelling perceived corporate citizenship and psychological contracts: a mediating mechanism of perceived job efficacy. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(2), 231–247.

Chen, Y., Ferris, D. L., Kwan, H. K., Yan, M., Zhou, M., & Hong, Y. (2013). Self-love’s lost labor: a self-enhancement model of workplace incivility. Academy of Management Journal, 56(4), 1199–1219. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0906

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: a quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

Cortina, L. M. (2008). Unseen injustice: incivility as modern discrimination in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 33(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2008.27745097

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Leskinen, E. A., Huerta, M., & Magley, V. J. (2013). Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations: evidence and impact. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1579–1605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311418835

Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.6.1.64

Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2009). Patterns and profiles of response to incivility in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(3), 272. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014934

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Magley, V. J., & Nelson, K. (2017). Researching rudeness: the past, present, and future of the science of incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 299. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000089

Epitropaki, O. (2013). A multi-level investigation of psychological contract breach and organizational identification through the lens of perceived organizational membership: testing a moderated–mediated model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(1), 65–866.

Evans, W. R., & Davis, W. (2014). Corporate citizenship and the employee: an organizational identification perspective. Human Performance, 27(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2014.882926

Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1086/209351

Giumetti, G. W., Hatfield, A. L., Scisco, J. L., Schroeder, A. N., Muth, E. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (2013). What a rude e-mail! Examining the differential effects of incivility versus support on mood, energy, engagement, and performance in an online context. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(3), 297. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032851

Gopalan, N., Pattusamy, M., & Goodman, S. (2022). Family incivility and work-engagement: moderated mediation model of personal resources and family-work enrichment. Current Psychology, 41(10), 7350–7361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01420-4

Grappi, S., Romani, S., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2013). Consumer response to corporate irresponsible behavior: Moral emotions and virtues. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1814–1821. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.002

Guo, J., Qiu, Y., & Gan, Y. (2022). Workplace incivility and work engagement: the mediating role of job insecurity and the moderating role of self-perceived employability. Managerial and Decision Economics, 43(1), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3377

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F., Montoya, A. K., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equation modeling. Australasian Marketing Journal (AMJ), 25(1), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001

He, H., & Brown, A. D. (2013). Organizational identity and organizational identification: a review of the literature and suggestions for future research. Group & Organization Management, 38(1), 3–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601112473815

Hershcovis, M. S. (2011). “Incivility, social undermining, bullying… oh my!”: a call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(3), 499–519.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Huang, H. T., & Lin, C. P. (2019). Assessing ethical efficacy, workplace incivility, and turnover intention: a moderated-mediation model. Review of Managerial Science, 13(1), 33–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0240-5

Itzkovich, Y., & Dolev, N. (2017). The relationships between emotional intelligence and perceptions of faculty incivility in higher education. Do men and women differ? Current Psychology, 36(4), 905–918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9479-2

Jawahar, I. M., & Schreurs, B. (2018). Supervisor incivility and how it affects subordinates’ performance: a matter of trust. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-01-2017-0022

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Managment Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

Katz, D., Blasius, K., Isaak, R., Lipps, J., Kushelev, M., Goldberg, A., & DeMaria, S. (2019). Exposure to incivility hinders clinical performance in a simulated operative crisis. BMJ Quality & Safety, 28(9), 750–757. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs2019-009598

Kline, R. B. (2011). Convergence of structural equation modeling and multilevel modeling. In M. Williams, & W. P. Vogt (Eds.), Handbook of Methodological Innovation in Social Research Methods (pp. 562–589). London: Sage.

Knight, C., Patterson, M., & Dawson, J. (2017). Building work engagement: a systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions: effectiveness of Work Engagement Interventions. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 792–812. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2167

Kuijpers, E., Kooij, D. T., & van Woerkom, M. (2020). Align your job with yourself: the relationship between a job crafting intervention and work engagement, and the role of workload. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 25(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000175

Leiter, M. P., Day, A., Oore, D. G., & Spence Laschinger, H. K. (2012). Getting better and staying better: assessing civility, incivility, distress, and job attitudes one year after a civility intervention. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(4), 425. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029540

Lim, S., Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Personal and workgroup incivility: impact on work and health outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 95. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.95

Liu, W., Zhou, Z. E., & Che, X. X. (2019). Effect of workplace incivility on OCB through burnout: the moderating role of affective commitment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(5), 657–669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9591-4

Loh, J. M., Thorsteinsson, E. B., & Loi, N. M. (2021). Workplace incivility and work outcomes: cross-cultural comparison between australian and singaporean employees. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 59(2), 305–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12233

Lyu, Y., Zhu, H., Zhong, H. J., & Hu, L. (2016). Abusive supervision and customer-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: the roles of hostile attribution bias and work engagement. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 69–80.

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, N. P., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2018). Individual and organizational level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors. In P. M. Podsakoff, S. B. MacKenzie, & N. P. Podsakoff (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior (pp. 105–148). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: a partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13(2), 103–123.

Mao, C., Chang, C. H., Johnson, R. E., & Sun, J. (2019). Incivility and employee performance, citizenship, and counterproductive behaviors: implications of the social context. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(2), 213. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000108

Mann, A., & Harter, J. (2016). The worldwide employee engagement crisis. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/businessjournal/188033/worldwideemployeeengagementcrisis.aspx?Fg_source=Business%20Journal&g_medium=CardRelatedItems&g_campaign=tiles

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Neall, A. M., & Tuckey, M. R. (2014). A methodological review of research on the antecedents and consequences of workplace harassment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(2), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12059

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). Organizational tenure and job performance. Journal of Management, 36(5), 1220–1250. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309359809

Onaran, S. O., & Göncü-Köse, A. (2022). Mediating processes in the relationships of abusive supervision with instigated incivility, CWBs, OCBs, and multidimensional work motivation. Current Psychology, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03128-5

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington books/DC

Osatuke, K., Moore, S. C., Ward, C., Dyrenforth, S. R., & Belton, L. (2009). Civility, respect, engagement in the workforce (CREW) nationwide organization development intervention at Veterans Health Administration. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 45(3), 384–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886309335067

Pearson, C. M., & Porath, C. L. (2005). On the nature, consequences and remedies of workplace incivility: no time for “nice”? Think again. Academy of Management Perspectives, 19(1), 7–18.

Porath, C., & Pearson, C. (2013). The price of incivility. Harvard Business Review, 91(1–2), 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2013.767923

Porath, C. L., & Erez, A. (2007). Does rudeness really matter? The effects of rudeness on task performance and helpfulness. Academy of Management Journal, 50(5), 1181–1197. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.20159919

Porath, C. L., & Pearson, C. M. (2012). Emotional and behavioral responses to workplace incivility and the impact of hierarchical status. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42, E326–E357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.01020.x

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Richter, A. W., West, M. A., Van Dick, R., & Dawson, J. F. (2006). Boundary spanners’ identification, intergroup contact, and effective intergroup relations. Academy of Managment Review, 49(6), 1252–1269.

Rosen, C. C., Koopman, J., Gabriel, A. S., & Johnson, R. E. (2016). Who strikes back? A daily investigation of when and why incivility begets incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(11), 1620. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000140

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: a review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, S57–S88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job

Sliter, M., Jex, S., Wolford, K., & McInnerney, J. (2010). How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(4), 468. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020723

Spector, P. E., Bauer, J. A., & Fox, S. (2010). Measurement artifacts in the assessment of counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: do we know what we think we know? Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(4), 781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019477

Taylor, S. G., Bedeian, A. G., Kluemper, D. H. (2012). Linking workplace incivility to citizenship performance: The combined effects of affective commitment and conscientiousness. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33, 878–893. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314535432

Vasconcelos, A. F. (2020). Workplace incivility: a literature review. International Journal of Workplace Health Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-11-2019-0137

Wang, H. J., Lu, C. Q., & Siu, O. L. (2015). Job insecurity and job performance: the moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1249–1258. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038330

Williams, L. J., & O’Boyle Jr, E. H. (2008). Measurement models for linking latent variables and indicators: a review of human resource management research using parcels. Human Resource Management Review, 18(4), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.07.002

Young, K. A., Hassan, S., & Hatmaker, D. M. (2021). Towards understanding workplace incivility: gender, ethical leadership and personal control. Public Management Review, 23(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1665701

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Cihangir Gümüştaş and Nilgün Karataş Gümüştaş. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Cihangir Gümüştaş, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. There are no funding information or conflicts of interest to declare.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in this study.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gümüştaş, C., Karataş Gümüştaş, N. Workplace incivility and organizational citizenship behaviour: moderated mediation model of work engagement and organizational identity. Curr Psychol 42, 31448–31460 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04169-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-04169-6